Abstract

Population-based studies have demonstrated that increased retinal venular calibre is a risk factor for cardiac disease, cardiac events and stroke. Venular dilatation also occurs with diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia and autoimmune disease where it is attributed to inflammation. This study examined whether the inflammation associated with infections also affected microvascular calibre. Participants with infections and CRP levels > 100 mg/L were recruited from the medical wards of a teaching hospital and assisted to complete a demographic and vascular risk factor questionnaire, and to undergo non-mydriatic retinal photography (Canon CR5-45NM, Japan). They were then treated with appropriate antibiotics, and underwent repeat retinal imaging when their CRP levels had fallen to less than 100 mg/L. Retinal images were examined for arteriole and venular calibre using validated semi-automated software based on Knudtson’s modification of the Parr-Hubbard formula (IVAN, U Wisconsin). Differences in inflammatory markers and calibre were examined using the paired t-test for continuous variables. Determinants of calibre were calculated from multiple linear regression analysis. Forty-one participants with respiratory (27, 66%), urinary (6, 15%), skin (5, 12%), or miscellaneous (3, 7%) infections were studied. After antibiotic treatment, participants’ mean CRP levels fell from 172.9 ± 68.4 mg/L to 42.2 ± 28.2 mg/L (p < 0.0001) and mean neutrophil counts fell from 9 ± 4 × 109/L to 6 ± 3 × 109/L (p < 0.0001). The participants’ mean venular calibre (CRVE) decreased from 240.9 ± 26.9 MU to 233.4 ± 23.5 MU (p = 0.0017) but arteriolar calibre (CRAE) was unchanged (156.9 ± 15.2 MU and 156.2 ± 16.0 MU, p = 0.84). Thirteen additional participants with infections had a CRP > 100 mg/L that persisted at review (199.2 ± 59.0 and 159.4 ± 40.7 mg/L, p = 0.055). Their CRAE and CRVE were not different before and after antibiotic treatment (p = 0.96, p = 0.78). Hospital inpatients with severe infections had retinal venular calibre that decreased as their infections resolved and CRP levels fell after antibiotic treatment. The changes in venular calibre with intercurrent infections may confound retinal vascular assessments of, for example, blood pressure control and cardiac risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Examination of the retinal small vessels enables direct visualisation of structural and pathologic features of the microcirculation during life. Altered vessel calibre reflects the earliest sign of microvascular damage from systemic disease. Population-based studies suggest that retinal small vessel calibre predicts an increased risk of cardiac disease, cardiac events and stroke1. Arteriolar narrowing in men and venular dilatation in women correlate with this increased risk1. Coronary angiographic studies have found that calibre is related to more severe coronary disease and some types of intracoronary plaque2,3. Retinal microvascular disease also correlates with diastolic heart failure and progressive renal impairment2,4.

However microvascular calibre has multiple determinants. Arteriole calibre is smaller in men, with increased age, renal failure and poorly controlled hypertension5. Venular calibre is larger with smoking, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia6,7,8,9. Venular calibre is also larger in chronic inflammatory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease10, rheumatoid arthritis and SLE11. Calibre is not fixed but varies with physiological activity, for example, after haemodialysis12. The effect of acute infections on microvascular calibre has not been studied previously.

C reactive protein (CRP) is an acute phase reactant that is elevated in infections. It is synthesized by the hepatocytes in response to increased IL-613, and levels increase within 6 h of disease onset, and start to fall within 48 h of the response to antibiotic treatment14. CRP was previously considered a bystander in the inflammatory response, but recent evidence suggests that it is an inflammatory mediator that is inversely proportional to basal endothelial nitric oxide synthesis15,16, and hence potentially directly involved in endothelial dysfunction17,18 and vascular injury19. CRP also represents a non-traditional risk factor for cardiac disease itself20, since elevated CRP levels are an independent cardiovascular risk factor21 that is associated with a poorer clinical outcome22.

This study examined the effect of acute infections on retinal small vessel calibre because any changes might interfere with the ability to use calibre to assess blood pressure control or predict cardiac risk in individuals with coincidental infections.

Subjects and methods

Study design

This was a single centre paired observational study of individuals with infections who underwent assessment for retinal microvascular calibre before and after antibiotic treatment.

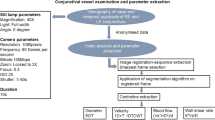

Consecutive individuals admitted over a 6 month period to a general medical ward with an infection and CRP level > 100 mg/L were invited to participate. Participants were assisted to complete a structured questionnaire that included demographic and medical details, as well as vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking history) and medications. Participants continued with their pre-existing treatment for hypertension and diabetes but were not allowed to smoke while in hospital. Relevant laboratory test results (CRP, FBE, neutrophil counts, albumin, eGFR) were obtained from their electronic medical records, and participants underwent non-mydriatic retinal photography. They were treated with antibiotics, and those whose CRP levels fell to levels < 100 mg/L underwent repeat retinal photography. Retinal images were then examined for arteriole and venular calibre at a grading centre by a trained grader.

Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, infections with an initial CRP level > 100 mg/L, and CRP < 100 mg/L after treatment. Exclusion criteria were bilateral ungradable retinal images. Data were also available for some individuals where the second CRP level was still > 100 mg/L.

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Northern Health, according to the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written, informed consent.

Retinal imaging and vessel calibre measurement

Digital retinal imaging was performed using a non-mydriatic retinal camera (Canon CR5-45, Tokyo). At least 2 standardised 45° colour digital images were taken of each eye, with one centred on the optic disc and the other on the macula. In general the right retina was examined on both occasions, but if this were ungradeable, the left was used.

Retinal arteriole and venular calibre were measured by a grader masked to subject identity and treatment, using a computer-assisted semi-automated imaging software (IVAN, University of Wisconsin) and a standardised protocol at the Centre for Eye Research Australia23,24. This identified the six largest arterioles and venules in a ring 0.5–1.0 disc diameters from the optic disc margin, and the Central Retinal Arteriole (CRAE) and Venular Equivalents (CRVE) were then determined from Knudtson’s revision of the Parr-Hubbard formula. Grading automatically took into account axial length. Fractals and tortuosity were not assessed because these were unlikely to change over the short period of follow-up. This grading method was highly reproducible in the laboratory with intra-grader coefficients of variation of 0.986 and 0.989 for CRAE and CRVE respectively11.

Statistical analysis

Differences in clinical and laboratory characteristics in individual subjects were compared using the paired t-test for continuous variables. The contributions of inflammatory and vascular risk factors to small vessel calibre were examined using univariate analysis and independent determinants from multivariate analysis (SPSS21.0). This was a pilot study and it was not possible to perform a power calculation since the effect of infections on calibre was not known. The aim was to generate hypotheses and no correction was performed for multiple analyses.

Results

Participant characteristics

Forty-one individuals fulfilled the conditions of recruitment where their initial CRP was > 100 mg/L, the follow up CRP was < 100 mg/L and where they had at least one gradable retinal image. The study cohort comprised 29 men (71%) and 12 women (29%) with a mean age of 65.7 ± 18.4 years (Table 1). Seventeen (41%) had hypertension, and the overall mean arterial pressure was 86 ± 12 mm Hg. Thirteen (32%) had diabetes, 9 had dyslipidemia (22%), and 31 (76%) were current or former smokers. Their mean eGFR was 65 ± 26 mL/min/1.73 m2. Study participants had infections of the respiratory tract (n = 27, 66%), urinary tract (6, 15%), skin (n = 5, 12%), or endocarditis (n = 3, 7%). They were treated with ceftriaxone (for respiratory, urinary tract infections), flucloxacillin (cellulitis) or ampicillin and gentamicin (endocarditis).

All participants had their second retinal photograph taken within 5 days of the first. Participants with hypertension continued their treatment unchanged during the study. Their commonest medications were angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors together with a calcium channel blocker where a second agent was required. Likewise participants with diabetes continued routine treatment. None was treated with a vasoconstrictive agent during the treatment period.

Measures of inflammation

The participants’ mean CRP level at recruitment was 172.9 ± 68.4 (range 106.4 to 402.3) mg/dL which fell after treatment to 42.2 ± 28.2 (range 7.6 to 96.8) mg/L (diff 130.6, 109.4 to 151.9, p < 0.0001) (Table 2). Their mean white cell count of 12 ± 5 × 109/L fell to 9 ± 3 × 109/L (diff 2.6, 1.4 to 3.6, p < 0.0001), and their mean neutrophil count of 9 ± 4 × 109/L fell to 6 ± 3 × 109/L (diff 2.5, 1.4 to 3.6, p < 0.0001) (Figs. 1, 2). Hb, serum albumin and eGFR levels were not different before and after antibiotic treatment.

Retinal vessel calibre

The participants’ mean arteriole calibre (CRAE, Central Retinal Arteriole Equivalent) was not different at recruitment and after treatment (156.9 ± 15.2 MU and 156.2 ± 16.0 MU respectively, diff 0.3, -2.5 to 3.0, p = 0.84) (Table 2).

However their mean venular calibre decreased from 240.9 ± 26.9 MU to 233.4 ± 23.5 MU (diff 8.8, 3.5 to 14.1 p = 0.0017) (Table 2).

The change in venular calibre correlated with initial white cell and neutrophil counts (p both < 0.01), but not with initial CRP, serum albumin, gender, hypertension, diabetes, smoking history dyslipidaemia, haemoglobin level or renal function (p all NS). The initial white cell count was the most significant determinant of increased venular calibre after multivariate stepwise regression (coefficient = 1.30, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.21, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Participants with follow-up CRP > 100 mg/L

Data were available for 13 further individuals with infections whose initial and follow-up CRP levels were both > 100 mg/L (means, SD, 199.2 ± 59.0 and 159.4 ± 40.7 mg/L respectively, (p = 0.055) (Tables 4 and 5). Their mean age was 55 ± 10 years, 10 were male (77%), 8 (62%) had hypertension, 2 had diabetes (15%) and one was a smoker (7%). Four had an upper respiratory tract (31%), two had a urinary tract (16%) and 7 (50%) had other infections (cellulitis, endocarditis, cholecystitis). Their changes in CRAE and CRVE after treatment were not significant (p = 0.96, p = 0.78 respectively).

Discussion

This study found that the retinal venular calibre in hospitalized patients with infections and CRP levels > 100 mg/L decreased when the follow-up CRP was < 100 mg/L after antibiotic treatment. There was no change in the arteriole calibre. There was also no change in calibre when individuals with infections were treated with antibiotics but their CRP levels did not fall below 100 mg/L. The reduction in venular calibre thus appeared to reflect the decrease in CRP level.

It is unlikely that the effect on venular calibre reflected the different types of infections or the antibiotics themselves since venular calibre did not change where the CRP level did not fall or when different antibiotics were used. It is also unlikely that smoking cessation in hospital or better blood pressure control was responsible for the change in calibre, because previous data suggest that the dilatation in smokers persists after they stop smoking10 and most patients' blood pressure measurements did not change during their treatment.

Population-based cohorts indicate that women with larger venules have an increased risk of cardiac events including stroke9, and coronary angiographic studies suggest that increased calibre correlates with cardiac events, coronary angiographic abnormalities and intracoronary plaque2,3,25. The reasons for these associations have been unclear. Diabetes, dyslipidemia and cigarette smoking are all traditional cardiac risk factors associated with venular dilatation, but venular dilatation is also associated with cardiac disease independent of these risk factors26,27. Non-traditional cardiac risk factors including obesity and rheumatoid arthritis also result in inflammation and venular dilatation9,28. Inflammation may have a direct effect on endothelial dysfunction and hence venular dilatation29. We are not arguing that transient infections predispose to macrovascular disease but rather that other sources of inflammation that are also cardiac risk factors such as diabetes and obesity may be responsible for the dilated venular calibre associated with cardiac events in large population-based studies. The transient venular dilatation that occurs with intercurrent infections may result in an erroneous assessment of high risk.

Retinal venular calibre reflects multiple systemic factors8,29,30,31,32 and is dynamic12. The initial white cell count in the cohort with infection was the only independent determinant of calibre identified after multivariate analysis. There was no association with CRP itself and the association with neutrophilia seen on univariate analysis did not persist. The observational nature of this study meant that it was not possible to exclude a shared cause for the increase in white cell counts and venular dilatation rather than the white cells directly affecting dilatation. However a study from Rotterdam similarly found that a higher white cell count was associated with larger venular diameter9, and that this was explained by the infection-induced leucocytosis being partly modulated by CRP level33,34.

Arteriole calibre was not altered in patients with active infections in this study. These results are consistent with previous findings that retinal venules, not arterioles, are dilated more in inflammation. Generally arteriole and venular calibre change in parallel, but arteriole calibre varies less, which may explain the lack of observable difference with infections noted here.

The strengths of this study were the careful characterization of participants, the highly reliable and reproducible method used for measuring microvascular calibre and the examination of individuals where the elevated CRP level persisted after antibiotic treatment. Although this cohort was smaller and younger, their calibre measurements still indicated that a lesser change in CRP was not associated with reduced venular calibre. The limitations of the study included that vessel calibre measurements from colour retinal images underestimate the vessel width because they measure the blood cell column rather than the peripheral plasma cuff that varies with the pulse cycle30,35.

It was unclear before this study was undertaken whether infections were associated with a change in retinal vessel calibre and indeed the amount of inflammation needed for any change. Very large population-based studies are required to detect a small change or to examine the effect of multiple covariates. This was a pilot study to determine the size of the effect, and a power calculation to determine the sample number was not possible. However similarly-sized studies examining venular calibre in inflammatory disease have also demonstrated a discernible change in calibre11.

It is unlikely that the decrease in venular calibre was due to intragrader variability because the retinal images were coded, and the grader was not aware of the nature of the study nor whether images were taken before or after antibiotic treatment. Although a number of potential participants were excluded because their CRP levels did not fall sufficiently or their images were not gradeable, there was no reason to believe that their clinical characteristics were the source of the different outcomes in calibre. The changes in calibre seen with infections lasted only a few days and were unaffected by other retinal structural parameters such as fractal dimensions or retinal nerve fibre layer thickness36,37.

The change in retinal venular calibre found here was small but may still be clinically relevant. Although some population-based studies exclude individuals with infections our results suggest that other kinds of inflammation associated with an increased CRP may affect calibre too, including coincidental gout, inflammatory arthritis, skin rashes, and surgery.

In summary, venular calibre may be affected reversibly in individuals with infections. Quantitative assessment of retinal microvascular calibre may be useful clinically in assessing blood pressure control or cardiac risk, or as a biomarker for risk stratification, for say, cardiac events. The present study demonstrates that hospital-based assessments of retinal microvascular calibre as a measure of blood pressure control or risk factor for cardiac disease must also consider coincidental infections and other sources of inflammation11 as potential confounders.

Data availability

The data is available in a deidentified format.

References

Wong, T. Y. et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA 287(9), 1153–1159. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.9.1153 (2002).

Cheng, L. et al. Microvascular retinopathy and angiographically-demonstrated coronary artery disease: A cross-sectional, observational study. PLoS ONE 13(5), e0192350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192350 (2018).

Wightman, A. et al. Small vessel disease and intracoronary plaque composition: a single centre cross-sectional observational study. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 4215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39989-3 (2019).

Ooi, Q. L. et al. The microvasculature in chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6(8), 1872–1878. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10291110 (2011).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and renal dysfunction: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15(9), 2469–2476. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASN.0000136133.28194.E4 (2004).

Kifley, A. et al. Long-term effects of smoking on retinal microvascular caliber. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166(11), 1288–1297. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm255 (2007).

Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Moss, S. E., Wong, T. Y. & Sharrett, A. R. Retinal vascular caliber in persons with type 2 diabetes: The Wisconsin Epidemiological Study of Diabetic Retinopathy: XX. Ophthalmology 113(9), 1488–1498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.028 (2006).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Associations between the metabolic syndrome and retinal microvascular signs: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45(9), 2949–2954. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.04-0069 (2004).

Ikram, M. K. et al. Are retinal arteriolar or venular diameters associated with markers for cardiovascular disorders? The Rotterdam Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45(7), 2129–2134. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.03-1390 (2004).

Chew, S. K. et al. Hypertensive/microvascular disease and COPD: A case control study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 41(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368544 (2016).

Okada, M. et al. Retinal venular calibre is increased in patients with autoimmune rheumatic disease: A case-control study. Curr. Eye Res. 38(6), 685–690. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2012.754046 (2013).

Tow, F. K. et al. Microvascular dilatation after haemodialysis is determined by the volume of fluid removed and fall in mean arterial pressure. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 35(6), 644–648. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341732 (2012).

Clyne, B. & Olshaker, J. S. The C-reactive protein. J. Emerg. Med. 17(6), 1019–1025 (1999).

Ballou, S. P. & Kushner, I. C-reactive protein and the acute phase response. Adv. Intern. Med. 37, 313–336 (1992).

Cleland, S. J. et al. Endothelial dysfunction as a possible link between C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 98(5), 531–535 (2000).

Venugopal, S. K., Devaraj, S., Yuhanna, I., Shaul, P. & Jialal, I. Demonstration that C-reactive protein decreases eNOS expression and bioactivity in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation 106(12), 1439–1441. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000033116.22237.f9 (2002).

Venugopal, S. K., Devaraj, S. & Jialal, I. C-reactive protein decreases prostacyclin release from human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation 108(14), 1676–1678. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000094736.10595.A1 (2003).

Verma, S. et al. Endothelin antagonism and interleukin-6 inhibition attenuate the proatherogenic effects of C-reactive protein. Circulation 105(16), 1890–1896. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000015126.83143.b4 (2002).

Fichtlscherer, S. et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and impaired endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 102(9), 1000–1006. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1000 (2000).

Braunwald, E. Shattuck lecture–cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: Triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N. Engl. J. Med. 337(19), 1360–1369. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199711063371906 (1997).

Ballou, S. & Cleveland, R. Binding of human C-reactive protein to monocytes: Analysis by flow cytometry. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 84(2), 329–335 (1991).

Li, J. J. et al. Elevated level of plasma C-reactive protein in patients with unstable angina: Its relations with coronary stenosis and lipid profile. Angiology 53(3), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/000331970205300303 (2002).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Computer-assisted measurement of retinal vessel diameters in the Beaver Dam Eye Study: Methodology, correlation between eyes, and effect of refractive errors. Ophthalmology 111(6), 1183–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.039 (2004).

Hubbard, L. D. et al. Methods for evaluation of retinal microvascular abnormalities associated with hypertension/sclerosis in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ophthalmology 106(12), 2269–2280. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(99)90525-0 (1999).

McGeechan, K. et al. Meta-analysis: retinal vessel caliber and risk for coronary heart disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 151(6), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00005 (2009).

Wong, T. Y. & McIntosh, R. Systemic associations of retinal microvascular signs: A review of recent population-based studies. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 25(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00288.x (2005).

Nguyen, T. T. et al. Retinal vascular caliber and brachial flow-mediated dilation: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Stroke 41(7), 1343–1348. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581017 (2010).

de Jong, F. J. et al. Retinal vessel diameters and the role of inflammation in cerebrovascular disease. Ann. Neurol. 61(5), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21129 (2007).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Retinal vascular caliber, cardiovascular risk factors, and inflammation: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47(6), 2341–2350. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-1539 (2006).

Sun, C., Wang, J. J., Mackey, D. A. & Wong, T. Y. Retinal vascular caliber: systemic, environmental, and genetic associations. Surv. Ophthalmol. 54(1), 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.003 (2009).

Leung, H. et al. Relationships between age, blood pressure, and retinal vessel diameters in an older population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44(7), 2900–2904. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.02-1114 (2003).

Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Knudtson, M. D., Wong, T. Y. & Tsai, M. Y. Are inflammatory factors related to retinal vessel caliber? The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 124(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.124.1.87 (2006).

Mortensen, R. F. & Zhong, W. Regulation of phagocytic leukocyte activities by C-reactive protein. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67(4), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlb.67.4.495 (2000).

Zhong, W. et al. Effect of human C-reactive protein on chemokine and chemotactic factor-induced neutrophil chemotaxis and signaling. J. Immunol. 161(5), 2533–2540 (1998).

Knudtson, M. et al. Variation associated with measurement of retinal vessel diameters at different points in the pulse cycle. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 88(1), 57–61 (2004).

Arnould, L. et al. Association between the retinal vascular network with Singapore “I” Vessel Assessment (SIVA) software, cardiovascular history and risk factors in the elderly: The Montrachet study, population-based study. PLoS ONE 13(4), e0194694. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194694 (2018).

Arnould, L. et al. Association between the retinal vascular network and retinal nerve fiber layer in the elderly: The Montrachet study. PLoS ONE 15(10), e0241055. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241055. (2020). Gabrielle, None; A. Bourredjem, None; R. Kawasaki, None; C. Binquet, None; A M. Bron, Aerie (C), Allergan (C), Baush and Lomb (C), Santen Pharmaceutical (C), Thea (C); C. Creuzot-Garcher, Allergan (C), Bayer (C), Horus (C), Novartis (C), Roche (C), Thea (C). This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Acknowledgements

Cara Fitt and Thao Vi Luong undertook this project while they were undergraduate students at the University of Melbourne We wish to thank staff and patients at Northern Health, and the grading team at the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F. recruited many of the study participants, recorded clinical details, took their retinal photographs, performed the statistical analysis and prepared a first draft of the manuscript; V.L., D.C. and K.L. also recruited study participants, recorded clinical details, and took their retinal photographs; A.H. oversaw the statistical analysis; L.H. was responsible for all the grading of retinal vessel calibre; D.C. taught the students how to take retinal photographs, supervised the retinal photography, and was responsible for trouble-shooting, and identifying and managing any incidental ocular abnormalities: J.S. supervised the project and produced the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fitt, C., Luong, T.V., Cresp, D. et al. Increased retinal venular calibre in acute infections. Sci Rep 11, 17280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96749-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96749-y

This article is cited by

-

Retinal small vessel dilatation in the systemic inflammatory response to surgery

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.