Abstract

This study aims to map the occurrence and distribution of Madrepora oculata and to quantify density and colony sizes across recently discovered coral mounds off Angola. Despite the fact that the Angolan populations of M. oculata thrive under extreme hypoxic conditions within the local oxygen minimum zone, they reveal colonies with remarkable heights of up to 1250 mm—which are the tallest colonies ever recorded for this species—and average densities of 0.53 ± 0.37 (SD) colonies m−2. This is particularly noteworthy as these values are comparable to those documented in areas without any oxygen constraints. The results of this study show that the distribution pattern documented for M. oculata appear to be linked to the specific regional environmental conditions off Angola, which have been recorded in the direct vicinity of the thriving coral community. Additionally, an estimated average colony age of 95 ± 76 (SD) years (total estimated age range: 16–369 years) indicates relatively old M. oculata populations colonizing the Angolan coral mounds. Finally, the characteristics of the Angolan populations are benchmarked and discussed in the light of the existing knowledge on M. oculata gained from the North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most ubiquitous and conspicuous reef-forming cold-water coral (CWC) species in the Atlantic Ocean are Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata1. For both species, information is available regarding their occurrence, distribution and physiological performance, and a lot of advances have been made to improve the understanding of their biology, ecology and environmental constraints in present and future scenarios2,3. However, the number of published studies addressing CWCs is largely biased towards L. pertusa4. Furthermore, most of the gathered knowledge on M. oculata is rather punctual and restricted to specific locations in the NE Atlantic4,5 and the Mediterranean Sea6,7. Despite the fact that the current research on M. oculata is locally limited, it is considered a cosmopolitan species just like L. pertusa. It has an extended geographical distribution ranging from northern Norway (Korallen Reef) at 70° N, 22° E8 to the sub-Antarctic (Drake Passage) at 60° S, 69° W9, shows a high abundance in the West (off Indonesia, Philippines and Japan10) and South Pacific (off New Zealand11), and has recently also been documented from the Central Pacific (Phoenix Islands Protected Area, Republic of Kirbati12). However, up until today regarding the entire Indian Ocean, limited records have been registered (Fig. 1). In some areas of the Mediterranean Sea, M. oculata dominates the CWC communities6,7,13,14,15,16 or even constitutes the only framework-building CWC17. In some areas of the NE Atlantic, it occurs in similar numbers as L. pertusa4. However, at most of the Atlantic sites explored so far, L. pertusa is by far the dominant reef-forming CWC species e.g.18,19,20,21,22.

Geographical distribution of Madrepora oculata and Madrepora carolina. The global map shows the distribution of the two reef-forming species of the genus Madrepora (sources: World Conservation Monitoring Centre of the United Nation Environmental Programme, UNEP-WCMC; Ocean Biogeographic Information System, OBIS). While a large number of records of M. oculata (yellow dots; live occurrences indicated by a red cross) is reported in the North Atlantic and the West and South Pacific, M. carolina (white dots) is endemic to the NW Atlantic. The red polygon highlights the study area off Angola in the SW Atlantic, where living M. oculata have been discovered for the first time. The map is based on the digital elevation model (DEM) CleanTOPO2 (an edited version of the SRTM30 Plus) published by Patterson (2006; http://www.shadedrelief.com/cleantopo2) and was created with ESRI ArcGIS Desktop 10.7.

Up to now, studies on the distribution pattern and population density of M. oculata have only been performed for few sites in the NE Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea4,7,15,23. The northernmost investigated locations are the Norwegian CWC reefs (specifically the Røst Reef), for which maximum colony densities of 0.06 patches m−2 have been reported23. Overall, the highest average values for population density are documented for the NE Atlantic sites (Iceland, Ireland, Bay of Biscay) with values ranging from 0.53 ± 0.61 (SD) colonies m−2 to 1.64 ± 1.19 (SD) colonies m−24, whereas M. oculata populations in the Mediterranean display average densities ranging from 0.11 ± 0.44 (SD) colonies m−2 (Cap de Creus canyon, Gulf of Lions7) to averages of 0.81 ± 1.87 (SD) colonies m−2 (Cabliers coral mound province, Alborán Sea15). In addition, although a more limited capacity to build large frameworks has been attributed to M. oculata, mostly due to the more fragile branches that the species displays1, some exceptions have been documented in the Mediterranean Sea, where remarkably large colonies of up to 1 m in height have recently been discovered in the Ligurian Sea24.

The physical–chemical properties of the ambient waters have a controlling influence on the physiology of M. oculata (and other CWCs) as revealed by various experimental studies. For example, M. oculata populations, thriving at temperatures of 12 °C in the Mediterranean Sea (Cap de Creus canyon), decrease their respiration and calcification rates when exposed to lowered temperatures25. Low pH conditions seem to have no effect on the calcification rate of M. oculata even after an exposure time of six months26. Studies on the influence of dissolved oxygen concentrations (DO) have only been conducted on L. pertusa27,28, providing diverging results. While L. pertusa populations from the NE Atlantic merely survive DO of > 3.3 mL L−127, populations collected from the NW Atlantic can withstand oxygen levels as low as 1.6 mL L−128. Additionally, a mixed assemblage of L. pertusa and M. oculata colonizing coral mounds off Mauritania—though in low numbers and spatially dispersed—are exposed to even lower DO of 1.0–1.3 mL L−129,30.

In this work, we present the unique records of M. oculata observed on coral mounds off Angola, where hypoxic conditions with DO as low as 0.5 mL L−1 prevail31,32. The main aims of this study are to map the occurrence of M. oculata on the explored Angolan coral mounds, to quantify density and distribution of the species, and to discuss the observed distribution pattern in relation to the environmental setting in the region. Furthermore, demographic patterns are investigated, and based on the relations between colony size and growth rates obtained from other CWC areas, an average age of the Angolan M. oculata colonies is estimated. The results are discussed in the light of the existing knowledge on the species in the NE Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea.

Results

Distribution and density patterns of the Angolan Madrepora oculata populations

Madrepora oculata was present on four of the six explored Angolan coral mounds (Buffalo, Castle, Scary, and Valentine mounds; Table 1), where a total of 83 colonies were discovered. The locations of these colonies were marked on high-resolution bathymetric maps (grid cell size: 10 m) providing detailed shaded-relief views of the mounds (Fig. 2b–e). The species was most abundant on Buffalo mound with 39 registered occurrences, followed by 30 on Castle, eight on Scary, and six on Valentine mound (Table 1). The overall average density of M. oculata-colonies including all coral mounds was 0.53 ± 0.37 (SD) colonies m−2, covering on average 1.25 ± 1.28 (SD) m−2 of the seafloor within the analyzed video frames (for details see Table 2).

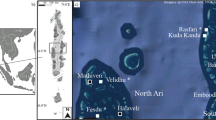

Occurrence of Madrepora oculata on the Angolan cold-water coral mounds. (A) Overview map of the Angolan coral mound province. Coral mounds for which ROV video footage was analysed are marked by boxes. Grey boxes indicate Snake mound (1) and Anna ridge (2), for which no Madrepora records have been documented; red boxes indicate the Valentine (B), Buffalo (C), Castle (D) and Scary (E) mounds being colonised by M. oculata. (B–E) Detailed maps of the Valentine, Buffalo, Castle and Scary coral mounds. ROV video transects (white line) crossing the respective mounds and identified locations of living M. oculata (blue dots) are indicated. Bathymetry data was acquired during R/V Meteror cruise M122 (Raw data is available under https://www2.bsh.de/daten/DOD/Bathymetrie/Suedatlantik/m122.htm).

Even though M. oculata occurred over a total bathymetric range of 330–470 m water depth (Table 3), the majority of colonies (91%, recorded on Castle, Scary and Buffalo mounds) thrived in a very narrow depth range between 330 and 390 m depth. Only on Valentine mound, deep occurrences below 420 m were registered (Table 3). Consistently, M. oculata colonies could not be located on the shallow Anna ridge and Snake mound (250–330 m water depth).

Madrepora colony size structure

An extraordinary large M. oculata framework was documented on Scary mound with a maximal height of 1250 mm (Figs. 3, 4). Two other remarkably large colonies were observed on Castle and Buffalo mounds with maximal heights of 1150 and 930 mm, respectively. Overall, the total height of the colonies varied between 250 and 1250 mm and colonies were on average 610 ± 210 (SD) mm high (Table 4). The scarce number of records from most locations did not allow for the performance of a proper analysis of the population structure. However, for Buffalo mound thirty-nine colonies were documented from which twenty M. oculata-colonies were suitable for measurements, most colonies were 400 to 600 mm high, but colonies of other size classes were also present. Sizes represented a typical Gauss distribution (Fig. 5). The alive/dead proportions of the measured colonies revealed similar length values for all colonies on all mounds with 170 ± 30 (SD) mm on average for the live part and 420 ± 170 (SD) mm for the dead part of the framework, respectively (Table 4).

Scaling of large Madrepora oculata framework (Scary mound, Angola). The ROV used for video surveys was equipped with two line lasers. The parallel green lines are the projected laser beams, which are 30 cm apart (the distance between the beams is depicted by a white line) and are used as a scale. Credits: photograph by MARUM ROV SQUID.

Extraordinary large Madrepora oculata framework of 1.2 m height observed on the Scary mound off Angola. (a) Panoramic view of the coral framework. (b) Zenithal view of the coral structure showing the different growing layers of the framework. Blue arrows indicate the Lophelia pertusa colonies in the vicinity of the large M. oculata framework. Credits: photographs by MARUM ROV SQUID.

Coral colony size structure of the Angolan Madrepora oculata population. The number of M. oculata specimens for each defined colony size-class (given in mm) is depicted in this graph. They were documented for the Angolan mounds: (a) Castle, (b) Scary, (c) Buffalo, (d) Valentine, and (e) displays a compilation of all mounds.

Estimation of Madrepora oculata colony ages

The estimated ages of the Angolan M. oculata colonies (considering available growth rates from the literature that vary between 3 and 18 mm year−133,34,35) showed a range of 16 to 369 years and exhibited an average age of 95 ± 76 (SD) years (SD; Table 5).

Local environmental conditions

Environmental parameters recorded by the ROV-CTD corresponding to the total depth range of living M. oculata-colonies (330–470 m) varied between 0.5 and 1.3 mL L−1 with regards to DO (range of mean values obtained for each of the four mounds (meanrange): 0.7–0.9 mL L−1), 7.8 and 12.2 °C regarding the temperature (meanrange: 8.1–10.3 °C), and between 34.6 and 35.2 in relation to salinity (meanrange: 34.7–35.0; Table 3; Fig. 6). Interestingly, prior studies presented slightly larger ranges regarding DO (0.5 and 1.5 mL L−1) and temperatures (6.8–14.2 °C). These studies additionally incorporated repeated measurements by a conventional CTD through the water column and long-term measurements by benthic landers, and explained the higher variability in DO and temperature by the effect of internal waves and the larger geographical coverage31,32. With regards to the shallow mound sites with no M. oculata occurrence (Anna ridge, Snake mound), DO revealed similarly low values, while temperature and salinity were slightly higher than for the other mounds (Table 3; Fig. 6). In contrast, for the deepest part of Valentine mound (480–500 m), for which also no M. oculata occurrences were recorded, DO were slightly higher than for the other mounds, while temperature and salinities were significantly lower (Table 3).

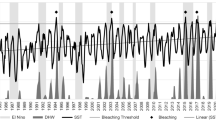

Depth distribution of Madrepora oculata and the corresponding environmental envelope off Angola. The water-mass properties (i.e. dissolved oxygen concentrations (DO), temperatures and salinities) were recorded with the ROV-mounted CTD during video surveys across various Angolan coral mounds (see legend for colour code; data for DO and temperatures were originally published in Hebbeln et al.32). Live colonies of M. oculata (diamond symbols) were only observed on Castle (n = 30), Scary (n = 8), Buffalo (n = 39), and Valentine (n = 6) mounds. Depth levels of live M. oculata occurrences are highlighted by horizontal grey bars.

Discussion

Despite the rather extreme environmental setting along the Angolan margin with overall very low DO (minimum DO: 0.5 mL L−1) and rather high temperatures (maximum temperatures: 14.2 °C31,32), which, according to previous studies, is expected to cause severe stress on deep-sea benthic organisms such as CWCs28,36, vivid and large reef structures were found to be widely distributed there. The coral community in this location was dominated by L. pertusa32. However, even though, M. oculata was found in comparably low numbers of live and dead colonies (Fig. 2, Table 1), the average density of M. oculata thriving on the Angola coral mounds (0.53 ± 0.37 (SD) colonies m−2) was in the same order of magnitude as previously documented for the Mediterranean Sea (0.30 ± 1.14 (SD) to 0.81 colonies m−27,15). However, it was lower than those reported for sites in the NE Atlantic (1.04 ± 0.80 (SD) to 1.64 ± 1.19 (SD) colonies m−24). In contrast, the percental coverage data of M. oculata obtained for the Angolan coral mounds (0.29 to 1.74 ± 1.67 (SD) coverage m−2; Table 2) was clearly higher than the range of values previously documented for the NE Atlantic (0.01 ± 0.03 (SD) to 0.04 ± 0.04 (SD) coverage m−24). This pattern might be related to the exceptional large colonies with heights of up to 1125 mm that were documented for the Angola coral mounds (Table 4). The reason for this different demographic pattern is unclear at this point. However, it is well known that recruitment (in plants) is a result of different processes like settlement, growth and mortality of seedlings37, which might also be applicable to coral larvae. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the M. oculata populations off Angola, comprising of few but large colonies, might experience less recruitment as reported for terrestrial forests. There, the presence of many small trees indicated ongoing recruitment, while forests with fewer but larger trees point to less intense recruitment37. Nevertheless, the population structure observed on Buffalo mound (where most M. oculata colonies were documented) indicates that the majority of the colonies had heights of 400–800 mm, while only a small amount of large (up to 930 mm in height) as well as of small colonies were present (Fig. 5). The low number of large colonies could be explained by the maximum size that colonies can reach due to physical constrains (e.g., maximal weight and height supported by the coral structure), whereas the low number of small colonies (recruits) might be a result of a so-called "demographic accident". This might be a result of highly variable larval supply recruitment, which results in a large number of individuals of the next size class (Bramanti pers. comm.). Such an event would explain why the M. oculata population on Buffalo mound appeared to be a growing population that has experienced a so called "recruitment accident" (Fig. 5).

Even if the overall low number of M. oculata recorded on the Angolan coral mounds avoids a robust statistical analysis, the depth-related environmental changes—in particular changes of DO and temperature measured with the CTD during the ROV video observations in the direct vicinity of the coral communities (Fig. 6; Table 3) - provide first insights into potential controls of their distribution and colony size spectrum. This might be an explanation for the observed intra-mound variability (Tables 2, 4). Regardless of the presence or absence of M. oculata, DO were very low ranging from 0.5 to 1.3 mL L−1 (Table 3) at all depths analysed (250–500 m). The majority of M. oculata-colonies (91%) as well as the largest colony sizes (930–1250 mm; Table 4) were documented between 330 and 390 m water depth (Castle, Scary, and Buffalo mounds), which correspond to DO of only 0.5 and 0.9 mL L−1 (Fig. 6, Tables 3, 4). Despite the moderate fluctuations, these values are by far the lowest DO previously observed for living CWCs (North Atlantic: ~ 1–2 mL L−118,29,38). Nevertheless, they are slightly above values reported for an extinct coral population on the Namibia shelf, where DO of below 0.5 mL L−1 prevents a present-day coral colonization31 and even may have caused their local extinction about 4500 years ago39. However, the presence of vivid CWC reefs off Angola indicates that the prevailing low DO constitute no severe stressor per se and that the Angolan coral communities have adapted to such low oxygen levels32. It is assumed that the high amount and quality of food off Angola (illustrated by a high net primary production (NPP) of > 3400 g C m−2 day−1, see Table 6) counteract potential deleterious effects of hypoxia31. Additionally, aquaria experiments demonstrated that continuous food supply can neutralize or at least minimize the negative effects of some stressors on the corals´ metabolism allowing them to withstand extreme conditions40,41. A further explanation is offered by a recent study showing that L. pertusa lives in symbiosis with microbes that provide new nitrogen sources, compensating for losses caused by enhanced metabolic activity due to stressful environmental conditions42, such as the hypoxia off Angola.

In contrast to the DO, the temperature data recorded during the video surveys off Angola show some distinct variations through depth that correlate well with the occurrence and density patterns of M. oculata. For the depth interval 330–390 m, where the most abundant and largest colonies have been documented, mean temperatures range from 8.4 to 10.3 °C (Table 3). In contrast, temperatures are considerably higher (mean: 11–12 °C) at shallower depths (250–330 m, Anna ridge and Snake mound) and slightly lower (mean: < 8 °C) at deeper depths (> 470 m, deep part of Valentine mound), where no living specimens were documented (Tables 1, 2). Therefore, the observed rather narrow temperature window is seemingly most suitable for the Angolan M. oculata populations, and interestingly, it perfectly matches the preferred temperature range (8.5–10 °C) reported for living M. oculata occurrences in the North Atlantic43. Consequently, as the overall prevailing hypoxic conditions already pose a certain degree of stress to the Angolan CWCs, it is possible that M. oculata is not capable to compensate a further stressor, such as temperatures above or below its preferred temperature range.

A comparison of the environmental setting off Angola with environmental conditions prevailing in some Atlantic and Mediterranean reef sites, where M. oculata is present, shows a distinct trend regarding temperature, salinity, DO, and NPP (data compiled from various sources (29,44,45,46; see Table 6). Madrepora oculata thrives in a wide thermal envelope ranging from cold temperatures of ~ 6 °C at the most northern CWC sites off Norway and Ireland to ~ 12 °C off Angola, and even up to 13 °C in the Mediterranean Sea (Table 6). This remarkably wide thermal tolerance of M. oculata has previously been documented in aquaria experiments25. In contrast, salinities corresponding to occurrences of M. oculata in the Atlantic show rather small fluctuations and vary between 34.6 and 35.7, whereas the species tolerates values of up to 38.1 in the western Mediterranean Sea (Table 6). Even more impressive, M. oculata displays a wide (inter-regional) tolerance for DO as the species occurs under maximum values of 6.7 mL L−1 off Norway, but also under minimum values as low as 0.5 mL L−1 off Angola. The NPP data shows an opposite trend with the highest NPP corresponding to the southern upwelling areas off Mauritania and Angola (Table 6). On the one hand, this negative correlation between DO and NPP can be explained by the increased oxygen consumption due the remineralization of high fluxes of organic matter. On the other hand, the high availability of food might in turn compensate for the oxygen deficiency causing metabolic stress for the corals31,32,40. The interaction between DO (stressor) and food (compensator) has been assumed for the Angolan coral populations31, though aquaria experiments with L. pertusa reveal regionally dependent thresholds for DO27,28, which point to (a potentially genetic) regional adaptation30. This case exemplifies that we are still at the beginning of understanding how multiple factors control the proliferation of M. oculata (and other CWCs) and how local adaptation might enhance the complexity of the system. In this context, the estimated average age of 95 ± 76 (SD) years hints at fairly old M. oculata populations off Angola, which might underline that the species is capable to deal with the regional seasonal and even decadal environmental variability. However, it is questionable, if local adaptation capabilities of CWCs could keep pace with environmental changes related to global warming. Further, it should be taken into account that the ages presented here are only preliminary estimates and that growth rate measurements of Angolan specimens will be essential to confirm or readjust these age estimations.

Interestingly, M. oculata exhibits partially similar growth rates in regions with very different environmental conditions such as the Norwegian shelf and the Mediterranean canyons34,35 (Table 6). On the contrary, these experimental studies also indicated a high variability in growth rates among specimens collected from the same region34. Therefore, the (potentially) wide range of ages estimated for the Angolan M. oculata colonies (16–369 years; Table 5) might simply reflect the high intraspecific growth rate variability. In addition, regionally different environmental conditions might be one of the reasons for the overall highly variable colony dimensions (varying from some branches of a couple of centimetres to colonies of > 1 m height; e.g.,24,47) and plasticity (displaying different morphotypes and tissue coloration) documented for M. oculata at various sites in the Atlantic and Mediterranean (Fig. 7). In order to understand the response of marine species to environmental changes, it is essential to understand how phenotypic as well as genotypic characteristics have been shaped by the dispersal-selection balance through space and time48. The high phenotypic plasticity of M. oculata (Fig. 7) and the scarce knowledge on its phenology and genetic characteristics49, makes it difficult to identify the regionally important environmental factors and to decipher their complex interplay favouring (or suppressing) the occurrence, growth and longevity of M. oculata.

Variability of colony dimensions and morphotypes of Madrepora oculata documented for different regions in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. (a) off Norway (ca. 20 km southwest of Stornest off mid-Norwegian shelf break), 453 m depth, bushy morphotype, (b) off Ireland (Porcupine Seabight, Belgica coral mound province), 808 m depth, bushy morphotype, (c) Gulf of Mexico (West-Florida slope), 520 m depth, fan-shape morphotype, (d) Gulf of Biscay (Petit Sole canyon), 900 m depth, cauliflower morphotype, (e) off the U.S. (Florida Straits, west off Bimini), 468 m depth, bushy morphotype, (f) off Mauritania (Tamxat coral mound complex), 396 m depth, bushy morphotype, (g) western Mediterranean Sea (Gulf of Lions, Lacaze-Duthiers canyon), 350 m depth, fan-shape morphotype, (h) western Mediterranean Sea (Gulf of Lions, Cap de Creus canyon), 190 m depth, cauliflower morphotype, (i) off Angola (Scary mound), 335 m depth (this study), massive fan-shape morphotype. Credits: (a) Pål Buhl-Mortensen, Institute of Marine Research, Norway; (b,c,e) MARUM ROV CHEROKEE; (d) Ifremer, ROV Victor6000, BobEco2011; (f) Tomas Lundälv, Tjärnö Marine Laboratory, University of Gothenburg; (g) Dierk Hebbeln, MARUM; (h) JAGO, IFM-GEOMAR & ICM-CSIC; (i) MARUM ROV SQUID.

The observed regional differences highlight the importance of considering the environment as it might well be the case that environmental differences along geographical gradients play an equally important role as the species eco-physiological limits documented in the experimental works. Indeed, environmental factors can act as important selective agents shaping genotype and phenotype composition of populations50. Consequently, genotype and phenotype adaptations must be taken into consideration to improve the understanding of the geographical as well as the bathymetric distribution and performance of marine organisms on both global and regional scales.

Finally, the expected ocean warming and deoxygenation are predicted to be two of the most important changes affecting CWCs28,51. Furthermore, predictions anticipating a decline of fluxes of particulate organic carbon from the surface waters28,36 will result in a lower energy supply for the CWCs and, thus, potentially reducing their capabilities to cope with increasing stress. The most recent habitat suitability model for the North Atlantic anticipates a reduction of 30% of suitable habitats for M. oculata with a northern shift in median latitudinal distributions (ranging from 1.9° to 4.6° in latitude), and a shift of median suitable depths towards deeper waters3,28. However, the geographical differences reflected by the variability of environmental parameters compiled for various Atlantic reef sites with the occurrence of M. oculata further highlight the importance to integrate potential regional adaptions of the species considered, which will be a future challenge for upcoming habitat suitability models.

Methods

ROV video surveys

During the RV Meteor cruise M122 (ANNA) in 2016, coral mounds with thriving reefs at their summits were discovered along the Angolan continental margin52. These mounds extended over a distance of ~ 30 nautical miles (nm) and were limited to water depths of ~ 250–500 m (Fig. 2). High-resolution mapping with the two multibeam echosounder systems KONGSBERG EM710 and EM122 (for technical details see52) revealed that their morphologies ranged from complex mound structures to long ridges with heights of up to 100 m (Fig. 2). The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) MARUM-SQUID (manufactured by SAAB Seaeye, UK) was utilized during the cruise M122 to explore the seafloor´s benthic communities colonizing the Angolan coral mounds. During this cruise, a total of seven dives (transects) were performed crossing six coral mounds (see Table 1, Fig. 2). The ROV was equipped with five video and still cameras (for technical details see52). Out of these, the main camera for video documentation was the Insite Pacific MiniZEUS MKII—a full HD camera with a resolution of 2.38 megapixels. A DSPL Wide-i SeaCam with a considerably lower resolution of 750 × 576 pixels was used as a downward-looking camera providing a full overview of the area underneath the vehicle. An Imenco Tigershark still camera acquired images at a resolution of 12 megapixels. For size measurements of organisms on the seafloor, the ROV was further equipped with two Imenco Dusky Shark line lasers, which have the capacity to project two parallel laser beams (lines) at a distance of 30 cm.

Occurrence, density, coverage and size measurements of Madrepora oculata colonies based on ROV footage

The ROV video footage recorded by a MiniZEUS HD camera was visualized with the free software VLC to document and to further analyse the occurrence and distribution of M. oculata colonies on the coral mounds. In addition, screen shots were taken from the MiniZEUS video records, when the living and dead parts of the colonies were clearly visible and the laser beams were switched on for size calibration (Fig. 3). These screen shots were used to measure the dead and living parts of the individual colonies following the methodology of Vad et al.53 and using the free software Image J. For each measured colony (total number: 30), three to five repetitive measurements were taken to cover the intra-colonial variability.

The video frames recorded by the DSPL Wide-I SeaCam downward-looking camera were used to calculate species density and coverage of the seafloor as these provided (i) a complete coverage of the seafloor underneath the vehicle, and (ii) facilitated the calculation of the total area covered by using the two parallel laser beams as a scale. Downward-looking video frames appropriate for analyses were selected based on the detailed information regarding the colony locations documented in the MiniZEUS video footage. Despite the low resolution, it was possible to identify the colonies without difficulty as they stood out from the surrounding seafloor and other benthic organisms. Madrepora oculata-colonies were clearly visible in a total of 20 video frames, which were ultimately used to calculate the total area depicted in the video frame. The percentage of the area covered by M. oculata-colonies (expressed as coverage m−2) and the colony density (expressed as colonies m2) were determined by using the above-mentioned free software Image J. Due to the small number of colonies that could be measured (as a result of the limited number of suitable video frames), a statistical analysis regarding potential differences in occurrence among mounds was not feasible.

Age estimations of Madrepora oculata colonies

In order to estimate an average age for the Angolan colonies, the minimum and maximum heights measured for 30 M. oculata-colonies and the growth rates published for this species in other regions, were used, following the methodology of Vad et al.53. Growth rate estimations for M. oculata, ranging between 3 and 18 mm year−1, are available for the Mediterranean Sea, the Gulf of Biscay and off Norway, and derive from aquaria and radio carbon-dated specimens33,34,35. As the general environmental setting in the tropical South Atlantic (hypoxic, warm and highly productive31) differs considerably from those in the temperate NE Atlantic and Mediterranean, all available growth rates were considered in order to perform the age estimates for the Angolan M. oculata-colonies. All colony measures were averaged and standard deviations were calculated. Furthermore, the minimum and maximum values for colony heights were taken into consideration for the age estimations.

Data of water mass properties

During all video surveys, the ROV was additionally equipped with a CTD (Seabird SBE37) and water-mass properties (i.e. temperature, salinity and DO) were continuously recorded in the direct vicinity of the Angolan coral communities52. The ROV-CTD data have already been published to describe the occurrence of L. pertusa population thriving in the hypoxic and warm waters off Angolan32, and are used in this study to relate the distribution pattern of the M. oculata populations to variations of the hydrographic parameters. In addition, to comparing the Angolan environmental setting with environmental conditions of other CWC reef sites in the NE Atlantic (geographically stretching from Iceland to Mauritania) and the Mediterranean Sea, for which the occurrence of M. oculata is known, temperature, salinity and DO data were compiled which derived from published in situ measurements29,46 and/or the World Ocean Atlas (WOA1345). Moreover, data on the net primary productivity (NPP; applied here as a quantitative measure for the flux of organic material from the sea surface) were complemented for all regions used for comparison (derived from http://data.guillaumemaze.org/ocean_productivity44).

Data availability

The ROV-CTD-data are archived and can be retrieved at the World Data Center PANGAEA (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.904187). The ROV still images and screen captures as well as all the metadata on colony sizes, density, coverage and age analyses presented in this paper will also be archived in PANGAEA (https://www.pangaea.de).

References

Roberts, J. M., Wheeler, A. J., Freiwald, A. & Cairns, S. D. Cold-Water Corals. The Biology and Geology of Deep-Sea Coral Habitats. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Davies, A. J. & Guinotte, J. M. Global habitat suitability for framework-forming cold-water corals. Plos One 6, e18483 (2011).

Morato, T. et al. Climate-induced changes in the suitable habitat of cold-water corals and commercially important deep-sea fishes in the North Atlantic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 2181–2202. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14996 (2020).

Arnaud-Haond, S. et al. Two “pillars” of cold-water coral reefs along Atlantic European margins: Prevalent association of Madrepora oculata with Lophelia pertusa, from reef to colony scale. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II(145), 110–119 (2017).

Buhl-Mortensen, L., Olafsdottir, S. H., Buhl-Mortensen, P., Burgos, J. M. & Ragnarsson, S. A. Distribution of nine cold-water coral species (Scleractinia and Gorgonacea) in the cold temperate North Atlantic: Effects of bathymetry and hydrography. Hydrobiologia 759, 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-2116-x (2015).

Gori, A. et al. Bathymetrical distribution and size structure of cold-water coral populations in the Cap de Creus and Lacaze-Duthiers canyons (northwestern Mediterranean). Biogeosciences 10, 2049–2060. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-2049-2013 (2013).

Orejas, C. et al. Cold-water corals in the Cap de Creus canyon (north-western Mediterranean): Spatial distribution, density and anthropogenic impact. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 397, 37–51 (2009).

Buhl-Mortensen, P. Coral reefs in the Southern Barents Sea: Habitat description and the effects of bottom fishing. Mar. Biol. Res. 13, 1027–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000.2017.1331040 (2017).

Cairns, S. Antarctic and subantarctic Scleractinia. Antarctic Res. Ser. 34. https://doi.org/10.1029/AR034p0001 (1983).

Cairns, S. D. & Zibrowius, H. Cnidaria Anthozoa: Azooxanthellate Scleractinia from the Philippine and Indonesian regions. Mém. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. 172, 27–243 (1997).

Tracey, D., Rowden, A., Mackay, K. & Compton, T. Habitat-forming cold-water corals show affinity for seamounts in the New Zealand region. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 430, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09164 (2011).

Auscavitch, S. R. et al. Oceanographic drivers of deep-sea coral species distribution and community assembly on seamounts, islands, atolls, and reefs within the Phoenix Islands protected area. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00042 (2020).

Angeletti, L., Castellan, G., Montagna, P., Remia, A. & Taviani, M. “The Corsica channel cold-water coral province” (Mediterranean Sea). Front. Mar. Sci. 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00661 (2020).

Chimienti, G., Bo, M., Taviani, M. & Mastrototaro, F. in Mediterranean Cold-Water Corals: Past, Present and Future, Springer Series: Coral Reefs of the World (eds. Covadonga Orejas Saco del Valle & C. Jiménez) 213–243 (Springer, 2019).

Corbera, G. et al. Ecological characterisation of a Mediterranean cold-water coral reef: Cabliers Coral Mound Province (Alboran Sea, western Mediterranean). Prog. Oceanogr. 175, 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2019.04.010 (2019).

Freiwald, A. et al. The White Coral Community in the Central Mediterranean Sea revealed by ROV surveys. Oceanography 22, 58–74 (2009).

Fabri, M. C. et al. Megafauna of vulnerable marine ecosystems in French Mediterranean submarine canyons: Spatial distribution and anthropogenic impacts. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II(104), 184–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.06.016 (2014).

Brooke, S. & Ross, S. W. First observations of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa in mid-Atlantic canyons of the USA. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II(104), 245–251 (2014).

Cordes, E. E. et al. Coral communities of the deep Gulf of Mexico. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II(55), 777–787 (2008).

Frederiksen, R., Jensen, A. & Westerberg, H. The distribution of scleratinian coral Lophelia pertusa around the Faroe Islands and the relation to intertidal mixing. Sarsia 77, 157–171 (1992).

Hebbeln, D. et al. Environmental forcing of the Campeche cold-water coral province, southern Gulf of Mexico. Biogeosciences 11, 1799–1815. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-1799-2014 (2014).

Wienberg, C. et al. Franken Mound: Facies and biocoenoses on a newly-discovered “carbonate mound” on the western Rockall Bank, NE Atlantic. Facies 54, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-007-0118-0 (2008).

Purser, A. et al. Local variation in the distribution of benthic megafauna species associated with cold-water coral reefs on the Norwegian margin. Cont. Shelf Res. 54, 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2012.12.013 (2013).

Fanelli, E. et al. Cold-water coral Madrepora oculata in the eastern Ligurian Sea (NW Mediterranean): Historical and recent findings. Aquat. Conserv. 27, 965–975. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2751 (2017).

Naumann, M. S., Orejas, C. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Species-specific physiological response by the cold-water corals Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata to variations within their natural temperature range. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II(99), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.05.025 (2014).

Movilla, J. et al. Resistance of two mediterranean cold-water coral species to low-pH conditions. Water 6, 59–67 (2014).

Dodds, L. A., Roberts, J. M., Taylor, A. C. & Marubini, F. Metabolic tolerance of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa (Scleractinia) to temperature and dissolved oxgen change. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 349, 205–214 (2007).

Lunden, J. J., McNicholl, C. G., Sears, C. R., Morrison, C. L. & Cordes, E. E. Acute survivorship of the deep-sea coral Lophelia pertusa from the Gulf of Mexico under acidification, warming, and deoxygenation. Front. Mar. Sci. 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2014.00078 (2014).

Ramos, A., Sanz, J. L., Ramil, F., Agudo, L. M. & Presas-Navarro, C. in Deep-Sea Ecosystems Off Mauritania: Research of Marine Biodiversity and Habitats in the Northwest African Margin (eds. Ramos, A., Ramil, F., & Sanz, J.L.) 481–525 (Springer, 2017).

Wienberg, C. et al. The giant Mauritanian cold-water coral mound province: Oxygen control on coral mound formation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 185, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.02.012 (2018).

Hanz, U. et al. Environmental factors influencing cold-water coral ecosystems in the oxygen minimum zones on the Angolan and Namibian margins. Biogeosciences 16, 4337–4356 (2019).

Hebbeln, D. et al. Cold-water coral reefs thriving under hypoxia. Coral Reefs 39, 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-020-01934-6 (2020).

Montero-Serrano, J.-C. et al. Decadal changes in the mid-depth water mass dynamic of the Northeastern Atlantic margin (Bay of Biscay). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 364, 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.01.012 (2013).

Orejas, C., Gori, A. & Gili, J. M. Growth rates of live Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata cold-water coral species maintained in aquaria. Coral Reefs 27, 255 (2008).

Sabatier, P. et al. 210Pb-226Ra chronology reveals rapid growth rate of Madrepora oculata and Lophelia pertusa on world’s largest cold-water coral reef. Biogeosciences 9, 1253–1265. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-1253-2012 (2012).

Sweetman, A. et al. Major impacts of climate change on deep-sea benthic ecosystems. Elementa-Sci. Anthrop. 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.203 (2017).

Lexerød, N. L. Recruitment models for different tree species in Norway. For. Ecol. Manag. 206, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.11.001 (2005).

Georgian, S. et al. Biogeographic variability in the physiological response of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa to ocean acidification. Mar. Ecol. 37. https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12373 (2016).

Tamborrino, L. et al. Mid-Holocene extinction of cold-water corals on the Namibian shelf steered by the Benguela oxygen minimum zone. Geology 47, 1185–1188. https://doi.org/10.1130/g46672.1 (2019).

Büscher, J., Form, A. & Riebesell, U. Interactive effects of ocean acidification and warming on growth, fitness and survival of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa under different food availabilities. Front. Mar. Sci. 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00101 (2017).

Connolly, S., Lopez-Yglesias, M. & Anthony, K. Food availability promotes rapid recovery from thermal stress in a scleractinian coral. Coral Reefs 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-012-0925-9 (2012).

Middelburg, J. J. et al. Discovery of symbiotic nitrogen fixation and chemoautotrophy in cold-water corals. Sci. Rep. 5, 17962. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17962 (2015).

Wienberg, C. & Titschack, J. in Marine Animal Forests: The Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots (eds. Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., & del Valle, C.O.S.) 699–732 (Springer, 2017).

Behrenfeld, M. J. & Falkowski, P. G. Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1–20 (1997).

Levitus, S. & Mishonov, A. World Ocean Atlas 2013 (Vers. 2). NOAA Atlas NESDIS 73. National Oceanographic Data Center, Ocean Climate Laboratory United States, National Environmental Satellite Data Information Service (2013).

Mienis, F. et al. Hydrodynamic controls on cold-water coral growth and carbonate-mound development at the SW and SE Rockall Trough Margin, NE Atlantic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I(54), 1655–1674 (2007).

Sanfilippo, R. et al. Serpula aggregates and their role in deep-sea coral communities in the southern Adriatic Sea. Facies 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-012-0356-7 (2013).

Hoey, J. A. & Pinsky, M. L. Genomic signatures of environmental selection despite near-panmixia in summer flounder. Evolut. Appl. 11, 1732–1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12676 (2018).

Boavida, J., Becheler, R., Addamo, A. M., Sylvestre, F. & Arnaud-Haond, S. in Mediterranean Cold-Water Corals: Past, Present and Future, Springer Series: Coral Reefs of the World (eds. Covadonga Orejas Saco del Valle & C. Jiménez) (Springer, 2019).

Sanford, E. & Kelly, M. W. Local adaptation in marine invertebrates. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142756 (2011).

Frank, N. et al. Northeastern Atlantic cold-water coral reefs and climate. Geology 39, 743–746. https://doi.org/10.1130/g31825.1 (2011).

Hebbeln, D. et al. ANNA cold-water coral ecosystems off Angola and Namibia. Cruise No. M122, December 30, 2015–January 31, 2016, Walvis Bay (Namibia) - Walvis Bay (Namibia). METEOR-Berichte, M122. DFG-Senatskommission Ozeanogr. 74. https://doi.org/10.2312/cr_m122 (2017).

Vad, J., Orejas, C., Moreno-Navas, J., Findlay, H. S. & Roberts, J. M. Assessing the living and dead proportions of cold-water coral colonies: Implications for deep-water marine protected area monitoring in a changing ocean. PeerJ 5, e3705. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3705 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere gratitude to the crew and scientific team aboard the RV Meteor cruise M122 for their on-board assistance. We also feel indebted to N. Nowald, C. Seiter, V. Vittori and T. Leymann from the ROV SQUID team at MARUM (University of Bremen). The research leading to the results in this manuscript received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 iAtlantic project (Grant Agreement No. 818123) (CO, DH). This manuscript reflects the authors’ view alone, and the European Union cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. We also like to thank the German Science Foundation (DFG) for enabling the RV Meteor cruise M122 and for supporting the Cluster of Excellence “The Ocean Floor—Earth’s Uncharted Interface” (Germany´s Excellence Strategy—EXC-2077—390741603 of the DFG) (DH, CW, JT). CO and LT have been supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). We greatly acknowledge S. Arnaud-Haond, T. Lundälv and P. Buhl-Mortensen for providing underwater images of Madrepora oculata. The authors would like to thank S. Böske da Costa for proof-reading this paper and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Enrique Orejas, father of the first author; who passed away during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.O. generated the idea behind the paper and created the concept of this manuscript in cooperation with C.W. C.W. and D.H. coordinated the scientific cruise and planned the ROV dives. C.O. performed the ROV image and data analyses for Madrepora oculata data. Together with L.T., J.T. and D.H., C.O. and C.W. prepared all of the figures and tables. C.O. and C.W. wrote the first draft and all authors interpreted the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Orejas, C., Wienberg, C., Titschack, J. et al. Madrepora oculata forms large frameworks in hypoxic waters off Angola (SE Atlantic). Sci Rep 11, 15170 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94579-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94579-6

This article is cited by

-

Trophic ecology of Angolan cold-water coral reefs (SE Atlantic) based on stable isotope analyses

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Natural variability in seawater temperature compromises the metabolic performance of a reef-forming cold-water coral with implications for vulnerability to ongoing global change

Coral Reefs (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.