Abstract

The prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is increasing. This study aimed to examine trajectories of BMI z-scores among Chinese children and the potential determinants including early individual, family and community factors. Group-based trajectory modeling was employed to identify BMI z-scores trajectories of children aged 2–18 years using the five waves data (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018) of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Multivariate logistic regression was conducted to determine the association between early individual, family, community factors and BMI z-scores trajectories of children. We identified three trajectories for boys and girls, named Class 1 as “not-overweight”, Class 2 as “persistent rapid descending but overweight during pre-school age”, and Class 3 as “rapid rising up to school age and then become-overweight” class. Macrosomia (OR 1.772; 95% CI 1.188–2.644) and being a single child (OR 2.038; 95% CI 1.453–2.859) were more likely to belong in Class 3 among boys. Girls living in the advantaged communities (OR 1.539; 95% CI 1.052–2.252), rural-living (OR 1.558; 95% CI 1.133–2.142) and with none social integration (OR 1.496; 95% CI 1.07–2.091) were more likely to belong in Class 2. There are heterogeneous BMI z-scores trajectories of children aged 2–18, and pre-school age is a critical window that could predict the long-term growth patterns. BMI z-scores trends need to be monitored during pre-school age, focusing on those at higher risk of later overweight obesity status, and targeted interventions at the early individual, family, community levels are essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is increasing, especially in developing countries1. According to the latest Chinese survey report, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 19% among children aged 6–17 and 10.4% among children under 62. It is estimated that by 2030, the direct economic cost of obesity-related chronic diseases will increase to 49.05 billion RMB per year3. Therefore, the trends in childhood overweight and obesity should be closely monitored. Estimating the patterns of different weight trajectories based on standardized BMI of children in the recent birth cohort, and taking effective measures can promote sustainable development of the society and economy.

The BMI z-score is often used to measure children’s overweight/obesity and to model relative children’s weight trajectories longitudinally4. A recent longitudinal study found that the average BMI z-scores trajectory decreased with age among Chinese children5. Another study used age- and sex-specific percentiles for BMI to define overweight/obesity, and found three different types of overweight/obesity trajectories among Chinese adolescents from 2010 to 20166. A small number of studies on the trajectory of overweight/obesity in Chinese children are available. Nevertheless, some of them only studied the trajectory of average BMI z-scores7, the heterogeneity of trajectory was not considered. Although some other studies6,8 used dichotomous variables such as overweight or obesity to estimate different trajectories, they did not comprehensively demonstrate the process of weight change by using the continuous variable of BMI z-scores. In order to fill these gaps, it is necessary to use BMI z-scores to explore different types of weight trajectories of Chinese children, so as to put forward more targeted measures for different weight trajectories.

Numerous scholars have found many factors that affect children’s overweight/obesity. At the individual level, the development of obesity may start early in an individual’s life. It is affected by prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal environmental factors9,10,11. Previous research has established that preterm infants are at a higher risk of developing childhood obesity than term infants, as low birth weight is often accompanied by rapid postnatal weight gain12. Moreover, there is growing evidence that breastfeeding protects against subsequent obesity13,14. At the family level, a large number of studies indicated that childhood obesity has a significant association with specific family characteristics, the prevalence of childhood obesity is highest in single-parent families, in lower-income households, and mothers with less educated15,16,17. At the community level, neighbor’s income inequality and ethnic composition are related to childhood obesity18,19. It has been found that food, physical activity and built environment have a deep impact on children’s weight status. The higher density of convenience stores is associated with a higher BMI z-score20. Moreover, children residing in the community with higher walkability, better access to public transit, and parks are less likely to be overweight21,22. In addition, the higher social integration between neighbors, the lower prevalence of obesity23.

The social-ecological theory divides these factors into different levels: individual level, family level, community/school level, and suggests that prevention strategies should be formulated according to different levels24,25. However, there are no comprehensive researches on socio-ecological determinants of overweight/obesity in Chinses recently born children, especially focusing on the BMI z-scores trajectory. Therefore, we draw on data from a new longitudinal survey in China to examine the trajectories of BMI z-scores among children and the potential determinants based on the social-ecological theory, including early individual, family and community factors. We hope to propose a more comprehensive and targeted intervention strategy about children’s overweight and obesity.

Results

BMI z-scores trajectories

The number of classes and the shape of BMI z-scores trajectories were estimated from 1913 boys and 1607 girls, respectively. From a 1-class model to a 6-class model, the 5-class model for boys and the 4-class model for girls yielded an even lower BIC. However, considering the average posterior probabilities for each subgroup > 0.7, the 3-class model was selected as the best fitting model for boys and girls, respectively. Table 1 shows the fit statistics for the trajectory classes estimated for boys and girls in CFPS. Figures 1 and 2, respectively show BMI z-scores trajectories for the 3-class model and the sizes of the three classes for boys and girls. We have identified three trajectories in both boys and girls that were similar in their growth patterns, but differed in their proportions. According to the relative position of the estimated three trajectories, we named Class 1 as “Not-overweight” (42.24% for boys, 52.98% for girls), Class 2 as “Persistent rapid descending but overweight during pre-school age” (41.55% for boys, 24.64% for girls), and Class 3 as “Rapid rising up to school age and then become-overweight ” (16.20% for boys, 22.38% for girls). Note that Class 3 had a stable pattern with overweight during puberty, especially among boys. Also, Tables 2 and 3 display the trajectory descriptions, the median posterior probabilities, and the growth parameter among boys and girls, respectively.

Baseline characteristics across different BMI z-scores trajectories

Table 4 presents the baseline characteristics across three BMI z-scores trajectories among boys and girls. At baseline, there was a significant difference in birth weight and single child between different BMI z-scores trajectories among boys (p < 0.05). Breastfeeding duration, family income, mother’s education, living location, community context degree, and social integration were significantly different between different BMI z-scores trajectories among girls (p < 0.05).

Association between BMI z-scores trajectories and early individual, family and community factors among boys

Table 5 summarizes the results from the multivariate logistic regression examining characteristics associated with trajectories membership among boys. Controlling for multivariate, boys living with parents (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.080–2.082), macrosomia (OR 1.772; 95% CI 1.188–2.644) and being a single child (OR 2.038; 95% CI 1.453–2.859) were risk factors for belonging in Class 3 trajectory than Class 1 trajectory. Boys with none social integration (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.018–1.711) were more likely to belong in Class 2 trajectory than Class 1 trajectory.

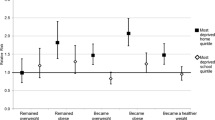

Association between BMI z-scores trajectories and early individual, family and community factors among girls

Table 6 summarizes the results from the multivariate logistic regression examining characteristics associated with trajectories membership among girls. Girls’ mother with junior/senior high school education (OR 0.658; 95% CI 0.489–0.886) and living with parents (OR 0.704, 95% CI 0.524–0.946) were less likely to belong in Class 2 trajectory than Class 1 trajectory. In contrast, girls living in the advantaged communities (OR 1.539; 95% CI 1.052–2.252), rural-living (OR 1.558; 95% CI 1.133–2.142) and with none social integration (OR 1.496; 95% CI 1.07–2.091) were more likely to belong in Class 2 trajectory than Class 1 trajectory. Girls having a longer breastfeeding duration(≥ 6 months) (OR 1.469; 95% CI 1.035–2.087) were more likely to belong in Class 3 trajectory than Class 1 trajectory.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to identify BMI z-scores trajectories among Chinese children aged 2–18 in the recent birth cohort and to assess the association between BMI z-scores trajectories and potential determinants based on the social-ecological model. Four main findings are worthy of further attention and discussion.

We identified three distinct BMI z-scores trajectories among boys and girls from CFPS: Not-overweight (Class 1), Persistent rapid descending but overweight during pre-school age (Class 2), and Rapid rising up to school age and then become-overweight (Class 3). The three growth pattern classes based on the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) standards show potential deviations from “ideal” weight values of children across age. In our study, 40–50% of boys and girls are consistently not overweight, and the proportion is smaller than other studies26,27,28, because we found a larger group (41.55% for boys, 24.64% for girls) with persistent rapid descending that means decreased-risk of overweight, suggesting that a high-risk overweight status may be changed in adolescence6. Also, we found that children with BMI z-scores having rapid rising during the pre-school age could have a stable pattern with overweight during puberty, especially among boys. Another study also found that the first 4 years of life is a critical developmental window where long-term growth patterns26. Hence, BMI z-scores trends need to be monitored during the pre-school age and pay attention to those at higher risk of later overweight obesity.

Besides, we found that early individual, family, and community factors were associated with different BMI z-scores trajectories. At the individual level, BMI z-scores trajectories are associated with the birth weight and the breastfeeding duration. Macrosomia is more likely to be overweight during puberty among boys. Previous studies have found that high birth weight was associated with an elevated risk of later obesity in adolescence, and this association was significant only among boys29,30. One possible reason may be the sexual difference in growth of body composition, bone and muscle growth during the prenatal period31. Girls with longer breastfeeding duration (≥ 6 months) have a higher risk of belonging to be overweight during puberty in this study. Another nationwide study in China also found that if children receive breastfeeding duration for too long, their BMI tends to be higher32. However, several previous studies of Western children have suggested that breastfeeding over six months may be associated with a lower BMI in children33,34. Further studies are needed to explore the relationship of breastfeeding with children’s BMI in China.

The family factors associated with BMI z-scores trajectories are mother’s education, single child, and living with parents. Boys as only-children have a high risk of become-overweight during puberty, consistent with the previous studies35,36,37. Only-children spend more time on sedentary activities, eating more frequently away from home, more western fast food, and drinking more soft drinks than children with siblings, making them more likely to become obese37,38,39. Girls with better educated mothers are less likely to be overweight during pre-school age, which may be related to reasonable parenting methods and awareness of their child’s weight status40. Living with parents is associated with a lower incidence of overweight/obesity during school-age among girls. Parents’ behavior is a critical source of modeling in dietary intake behavior for adolescent girls41, and parental engagement between 10 and 18 years was associated with a decline in obesity risk across adolescence42. However, boys living with parents have a higher risk for overweight/obesity during school-age, which may be related to the preference for sons over daughters in China43,44,45.

For community factors, community context degree and social integration have an influence on BMI z-scores trajectories. Girls’ BMI z-scores trajectories are affected by their community environment, which is in agreement with the results of other studies20,33,46,47,48. Boys are more likely to spend time with peers in another community or independently explore other areas, while girls may be restricted by their community, associated with less physical activity33,20,35,22,46,48. Girls living in most advantaged communities are more likely to belong to the persistent rapid descending but overweight during pre-school age trajectory. Some studies found that children’s residential environments are related to their early growth health49, and neighborhood socioeconomic status on obesity may be most salient before pre-adolescence50. We also found that boys and girls with none social integration are more likely to be overweight during pre-school age. Higher social integration has been found to be associated with spending fewer hours watching television, playing computer games, and engaging in social media51, which could reduce the risk of being overweight. In addition, rural-living girls are more likely to have higher BMI z-scores before school age. Along with rapid social, economic, and nutritional transitions in rural China8, more food has been accessible, and caloric intake has been greater than ever before39. Lack of professional health information and healthy lifestyle52, pre-school age children in rural are at greater risk of obesity and need more attention.

This study has several limitations. First, determining the optimal number of latent trajectories based group-based trajectory modeling, is a process guided by statistical fit indices and investigator’s discretion that might overestimate or underestimate the real number of trajectories53. Although this method has limitations, we try to select the optimal classification of trajectories according to optimal fitting evaluation criteria. Second, our sample was selected from a nationally representative data set but not every sample has observations of all ages, so there will be some missing values. The group-based trajectory modeling can make maximum use of all observations for fitting. Third, using self-reported weight and height to estimate BMI z-scores could have some outliers and bias the trajectories. We identified outliers according to WHO growth standards54 and regarded them as missing values, ensuring the reliability of data to the maximum extent. Small changes in the bias related to changing the reporter are unlikely to have a large effect on the overall polynomial function of each trajectory55. Fourth, the measure of community factors was based on the feelings and impressions about the members and communities, leading to possible errors or biases. We will use more objective indicators in future research. In addition, we could not adjust for all possible confounders concerning BMI z-scores, and our study did not distinguish between exclusive and partial breastfeeding56. Therefore, it remains possible that unrecognized confounders or those that are underestimated could be contributing to our results.

Despite these limitations, our study has the advantage of prospectively covering the whole period from childhood to adolescence. We identified three BMI z-scores trajectories among children aged 2–18 in the recently birth cohort. Moreover, under the conceptual framework of social-ecological theory, we found that early individual, family, and community factors are associated with BMI z-scores trajectories, and targeted interventions at individual, family, and community levels are vital.

Conclusions

There are heterogeneous BMI z-scores trajectories of children aged 2–18, and pre-school age is a critical window that could predict the long-term growth patterns. BMI z-scores trends need to be monitored during pre-school age with a focus on those at higher risk of later overweight obesity. In addition, early individual factors, family, and community factors were associated with different BMI z-scores trajectories, and there are sex differences. Maternal health should be managed to control macrosomia risks, reducing the risk of overweight during school age in boys. Also, more attention should be paid to BMI z-scores of girls in rural and advantaged communities, and propose targeted measures to reduce the risk of being overweight pre-school age. Targeted interventions at individual, family, and community levels are vital.

Methods

Materials

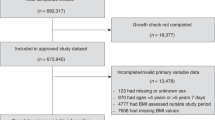

This study uses data from five waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which collect individual-, family-, and community-level longitudinal data. The baseline survey was conducted in 2010, using multistage probability proportional to size sampling. Counties/administrative equivalents were drawn from 25 selected provinces, and then communities were drawn from selected counties/administrative equivalents. The socioeconomic level was used as an indicator of implicit stratification at these two stages. At the third stage, 25 households were random drawn from each sampled community based on the onsite sampling frame, and members of every household were asked to participate in the survey. The baseline sample represents 95% of the Chinese population, for an approximately response rate of 79%57. The baseline sample in 2010 was then followed up in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018. Details of the sample design have been described in other study58 and the website http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/index.htm?CSRFT=XO4E-OIM2-ATE7-TX17-UW8H-99K1-6C5C-6Y5E.

We focused on children and adolescents aged 2–18 years old from five waves of the CFPS (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018). Children aged 2–10 years old (n = 4412) were included at the baseline, and followed in 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018. We took outliers of the dependent variable based on World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards54 as missing values. Children with more than three observations of the dependent variable were kept, resulting in an analytic sample of 3520. Then, we linked the children’s survey variables to family and community variables.

BMI z-scores trajectory

BMI z-scores trajectory is the dependent variable in this study, which often represents the physical growth and nutritional status of children and adolescents. Measured heights and weights for each child were obtained through self-reported and used to calculate BMI z-scores according to the IOTF standards59.

Early individual factors

Early individual factors included preterm birth, birth weight, and breastfeeding duration. Preterm birth was classified into two categories through the question “What is the gestational age of the child?”. The answer was coded “Yes” when less than 9 months and the other was code “No”. Birthweight was categorized as “macrosomia (birthweight ≥ 4 kg)”, “normal (2.5 kg < birthweight < 4 kg)” and “low birth weight (birthweight < 2.5 kg)” through the question “How many kilograms does the child weigh at birth?”. Breastfeeding duration was a categorical variable with two groups: < 6 months; and ≥ 6 months.

Family factors

Family factors included family income per year, mother’s education, living with parents and being a single child. Family income was divided into four quartiles (Q1–Q4), with Q1 and Q4 indicating the lowest and the highest incomes, respectively. Mother’s education included primary and below, junior/senior high school, and junior college and above. The single child was treated as a dichotomous variable (“Yes” and “No”). Living with parents was treated as a dichotomous variable (“Yes” and “No”).

Community factors

Community factors included living location, community context degree and social integration. Living location included urban and rural. Community context degree was a composite measure generated of six questions involving economic conditions, cleanliness of the road, the members' spiritual outlook, the homogeneity of the members, housing density, and the architectural pattern. Each question is based on the investigators’ feelings and impressions about the members and communities to evaluate, with scores from 1 to 7 scores. Community context degree was categorized into three classes (low, medium, and high) using latent profile analysis60. Social integration was classified into three categories (actively, rarely, and none), through the question “How many times did your family interact with your neighbors in the last month?”.

Statistical analysis

Two stages analysis approach was carried out to explore BMI z-scores trajectories of children in the recent birth cohort and the influencing factors of different trajectories. Firstly, group-based trajectory modeling with the censored normal model was used to identify BMI z-scores trajectories of children aged 2–18. Group-based trajectory modeling can identify distinctive clusters of individual trajectories within the population using maximum likelihood latent-class models in SAS PROC TRAJ61. Considering the sexual difference in the growth of boys and girls, we identified BMI z-scores trajectories for boys and girls, respectively. For each gender subgroup, latent class trajectory models from 1 to 6 classes were tested, allowing for a variety of different order polynomials in age (e.g., cubic, quadratic, linear) to determine the best fitting polynomial form. The optimal number of groups and shapes of trajectories were selected for the best fit to the data, as assessed by Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the change in BIC between models (estimate of logged Bayes factor-2ΔBIC) and the average posterior probabilities62. Usually, a better BIC is a smaller one and a tenfold difference in Bayes factor is considered meaningful. In addition, the average posterior probabilities ≥ 0.7 as a criterion for model selection. After reviewing model statistics, we chose the best and the most concise trajectory model, and the shape of each group’s trajectory and the probabilities of being in each group were output.

Secondly, multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for early individual factors, family, community factors related to BMI z-scores trajectories membership. According to the social-ecological theory, we started with individual factors and gradually added family and community factors. Therefore, three statistical models were tested: in Model 1, we controlled only for early individual factors: preterm birth, birth weight and breastfeeding duration. In Model 2, we added family factors: family income, mother education, living with parents and single child based on Model 1. In Model 3, we added community factors: living location, community context degree and social integration based on Model 2. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing data in the independent variables63. We conducted the same multivariate logistic regression models for boys and girls, respectively. All statistical procedures were performed by using the SAS 9.4.

Data availability

The original databases of this study are available from the online site: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/index.htm?CSRFT=XO4E-OIM2-ATE7-TX17-UW8H-99K1-6C5C-6Y5E.

References

Juonala, M. et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1876–1885. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1010112 (2011).

National Health Commission of the PRC. The Report on the Status of Nutrition and Chronic Diseases of Chinese Residents. (People's Medical Publishing House, China, 2020).

Ma, G. S. Report on Childhood Obesity in China. 15 (People's Medical Publishing House, China, 2017).

Must, A. & Anderson, S. E. Body mass index in children and adolescents: Considerations for population-based applications. Int. J. Obes. 30, 590–594. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803300 (2006).

Liang, J. et al. Community context, birth cohorts and childhood body mass index trajectories: Evidence from the China nutrition and health survey 1991–2011. Health Place. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102455 (2020).

Liang, Y. & Qi, Y. Developmental trajectories of adolescent overweight/obesity in China: Socio-economic status correlates and health consequences. Public Health 185, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.013 (2020).

Chen, Y.-L. et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes on the risk of overweight offspring: A population-based retrospective study in Xiamen, China. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58423-7 (2020).

Fu, Q. & George, L. K. Sex, socioeconomic and regional disparities in age trajectories of childhood BMI, underweight and overweight in China. Asian Popul. Stud. 11, 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2015.1038873 (2015).

Bernhardsen, G. P. et al. Early life risk factors for childhood obesity-Does physical activity modify the associations? The MoBa cohort study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 29, 1636–1646. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13504 (2019).

Koplin, J. J. et al. Infant and young child feeding interventions targeting overweight and obesity: A narrative review. Obes. Rev. 20, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12798 (2019).

Wood, C. T. et al. Antecedents of Obesity Among Children Born Extremely Preterm. Pediatrics 142, 8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0519 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Nutritional status and risk factors of overweight and obesity for children aged 9–15 years in Chengdu, Southwest China. BMC Public Health 12, 636. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-636 (2012).

Singhal, A. & Lanigan, J. Breastfeeding, early growth and later obesity. Obes. Rev. 8, 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00318.x (2007).

Wu, Y. Y., Lye, S., Dennis, C. L. & Briollais, L. Exclusive breastfeeding can attenuate body-mass-index increase among genetically susceptible children: A longitudinal study from the ALSPAC cohort. PLoS Genet. 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008790 (2020).

Dos Santos, C. S., Picoito, J., Nunes, C. & Loureiro, I. Early individual and family predictors of weight trajectories from early childhood to adolescence: Results from the millennium cohort study. Front. Pediatr. 8, 417. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00417 (2020).

Hankey, M. S. & Miyazaki, Y. Multilevel analysis of BMI growth trajectories of US school children: Features and risk factors. SSM Popul. Health 8, 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100455 (2019).

Nobari, T. Z., Whaley, S. E., Prelip, M. L., Crespi, C. M. & Wang, M. C. Trends in socioeconomic disparities in obesity prevalence among low-income children aged 2–4 years in Los Angeles County, 2003–2014. Child. Obes. 14, 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2017.0264 (2018).

Black, J. L. & Macinko, J. Neighborhoods and obesity. Nutr. Rev. 66, 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00001.x (2008).

Ludwig, J. et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—A randomized social experiment. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1509–1519. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 (2011).

Wall, M. M. et al. Patterns of obesogenic neighborhood features and adolescent weight a comparison of statistical approaches. Am. J. Prev. Med. 42, E65–E75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.009 (2012).

DeWeese, R. S. et al. Patterns of food and physical activity environments related to children’s food and activity behaviors: A latent class analysis. Health Place 49, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.11.002 (2018).

Ding, D. & Gebel, K. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: What have we learned from reviewing the literature?. Health Place 18, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.021 (2012).

Butel, J. et al. Estimating intervention dose of the multilevel multisite children’s healthy living program intervention. Transl. Behav. Med. 10, 989–997. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz073 (2020).

Ohri-Vachaspati, P. et al. The relative contribution of layers of the Social Ecological Model to childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr. 18, 2055–2066. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980014002365 (2015).

Noh, K. & Min, J. J. Understanding school-aged childhood obesity of body mass index: Application of the social-ecological framework. Child. Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/children7090134 (2020).

Ziyab, A. H., Karmaus, W., Kurukulaaratchy, R. J., Zhang, H. & Arshad, S. H. Developmental trajectories of Body Mass Index from infancy to 18 years of age: Prenatal determinants and health consequences. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 68, 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-203808 (2014).

Mustillo, S. et al. Obesity and psychiatric disorder: Developmental trajectories. Pediatrics 111, 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.4.851 (2003).

Li, C., Goran, M. I., Kaur, H., Nollen, N. & Ahluwalia, J. S. Developmental trajectories of overweight during childhood: Role of early life factors. Obesity 15, 760–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.585 (2007).

Eriksson, J., Forsen, T., Tuomilehto, J., Osmond, C. & Barker, D. Size at birth, childhood growth and obesity in adult life. Int. J. Obes. 25, 735–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801602 (2001).

Beltrand, J. et al. Post-term birth is associated with greater risk of obesity in adolescent males. J. Pediatr. 160, 769–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.10.030 (2012).

Yang, Z. et al. Association between birth weight and risk of abdominal obesity in children and adolescents: A school-based epidemiology survey in China. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09456-0 (2020).

Jing, H. Q. et al. Effect of breastfeeding on childhood BMI and obesity the China family panel studies. Medicine https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000000055 (2014).

Danielzik, S., Czerwinski-Mast, M., Langnase, K., Dilba, B. & Muller, M. J. Parental overweight, socioeconomic status and high birth weight are the major determinants of overweight and obesity in 5–7 y-old children: Baseline data of the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS). Int. J. Obes. 28, 1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802756 (2004).

Eny, K. M. et al. Breastfeeding duration, maternal body mass index, and birth weight are associated with differences in body mass index growth trajectories in early childhood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 107, 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx081 (2018).

Haugaard, L. K., Ajslev, T. A., Zimmermann, E., Angquist, L. & Sorensen, T. I. A. Being an only or last-born child increases later risk of obesity. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056357 (2013).

Cai, L. et al. One-child policy, weight status, lifestyles and parental concerns in Chinese children: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 72, 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0178-y (2018).

Ochiai, H. et al. Number of siblings, birth order, and childhood overweight: A population-based cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Public Health 12, 766. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-766 (2012).

Tian, X. & von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Are only children in China more likely to be obese overweight than their counterparts with siblings?. Econ. Hum. Biol. 37, 13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100847 (2020).

Hesketh, K., Crawford, D., Salmon, J., Jackson, M. & Campbell, K. Associations between family circumstance and weight status of Australian children. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477160601148554 (2007).

Ruiz, M. et al. Impact of low maternal education on early childhood overweight and obesity in Europe. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 30, 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12285 (2016).

Bauer, K. W., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Fulkerson, J. A., Hannan, P. J. & Story, M. Familial correlates of adolescent girls’ physical activity, television use, dietary intake, weight, and body composition. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-25 (2011).

Blewitt, C., Bergmeier, H., Macdonald, J. A., Olsson, C. A. & Skouteris, H. Associations between parent–child relationship quality and obesogenic risk in adolescence: A systematic review of recent literature. Obes. Rev. 17, 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12413 (2016).

Wang, V. H. et al. What factors may contribute to sex differences in childhood obesity prevalence in China?. Public Health Nutr. 21, 2056–2064. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018000290 (2018).

Moraeus, L. et al. Multi-level influences on childhood obesity in Sweden: Societal factors, parental determinants and child’s lifestyle. Int. J. Obes. 36, 969–976. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.79 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Body mass index trajectory and incident hypertension: Results from a longitudinal cohort of Chinese children and adolescents, 2006–2016. Am. J. Public Health 110, 1689–1695. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305873 (2020).

Roemmich, J. N., Epstein, L. H., Raja, S. & Yin, L. The neighborhood and home environments: Disparate relationships with physical activity and sedentary behaviors in youth. Ann. Behav. Med. 33, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3301_4 (2007).

Wolch, J. et al. Childhood obesity and proximity to urban parks and recreational resources: A longitudinal cohort study. Health Place 17, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.001 (2011).

Schaefer, S. E. et al. Social and environmental determinants of child physical activity in a rural mexican-origin community. J. Community Health 41, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0111-4 (2016).

Minh, A., Muhajarine, N., Janus, M., Brownell, M. & Guhn, M. A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: How, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter?. Health Place 46, 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.012 (2017).

Schroeder, K., Day, S., Konty, K., Dumenci, L. & Lipman, T. The impact of change in neighborhood poverty on BMI trajectory of 37,544 New York City youth: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09772-5 (2020).

Kimbro, R. T., Brooks-Gunn, J. & McLanahan, S. Young children in urban areas: Links among neighborhood characteristics, weight status, outdoor play, and television watching. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.015 (2011).

Gordon-Larsen, P., Wang, H. & Popkin, B. M. Overweight dynamics in Chinese children and adults. Obes. Rev. 15, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12121 (2014).

Nagin, D. S. & Odgers, C. L. In Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, Vol 6 Vol. 6 Annual Review of Clinical Psychology (eds NolenHoeksema, S., Cannon, T. D., & Widiger, T.) 109–138 (2010).

World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth Standards : Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight -for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development. (World Health Organization, 2006) https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43413.

Tu, A. W., Masse, L. C., Lear, S. A., Gotay, C. C. & Richardson, C. G. Body mass index trajectories from ages 1 to 20: Results from two nationally representative canadian longitudinal cohorts. Obesity 23, 1703–1711. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21158 (2015).

Rzehak, P. et al. Infant feeding and growth trajectory patterns in childhood and body composition in young adulthood. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106, 568–580. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.140962 (2017).

Xie, Y. & Hu, J. An Introduction to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chinese Sociological Review 47, 3–29. https://doi.org/10.2753/csa2162-0555470101 (2014).

Xie, Y. & Lu, P. The Sampling Design of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chin. J. Sociol. 1, 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150x15614535 (2015).

Cole, T. J. & Lobstein, T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 7, 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x (2012).

Oberski, D. Mixture models: Latent profile and latent class analysis. Vol. Modern statistical methods for HCI 275–287 (Springer, Cham, 2016).

Jones, B. L., Nagin, D. S. & Roeder, K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol. Methods Res. 29, 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124101029003005 (2001).

Nagin, D. Group-Based Modeling of Development. (Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press, 2005).

van Buuren, S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 16, 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280206074463 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The data were from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). We thank the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University for the CFPS data collection and analysis files. Thank you to the numerous staff members who have made tremendous efforts and selfless contributions to the CFPS investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and S.Z. participated in study conception, data interpretation, article drafting and revision. J.L. collated and analyzed the data. X.L. D.X. helped to revise the manuscript. P.W. contributed to the study design and critical revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, J., Zheng, S., Li, X. et al. Associations of community, famliy and early individual factors with body mass index z-scores trajectories among Chinese children and adolescents. Sci Rep 11, 14535 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93949-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93949-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.