Abstract

Yingjiang County, which is on the China–Myanmar border, is the main focus for malaria elimination in China. The epidemiological characteristics of malaria in Yingjiang County were analysed in a retrospective analysis. A total of 895 malaria cases were reported in Yingjiang County between 2013 and 2019. The majority of cases occurred in males (70.7%) and individuals aged 19–59 years (77.3%). Plasmodium vivax was the predominant species (96.6%). The number of indigenous cases decreased gradually and since 2017, no indigenous cases have been reported. Malaria cases were mainly distributed in the southern and southwestern areas of the county; 55.6% of the indigenous cases were reported in Nabang Township, which also had the highest risk of imported malaria. The “1–3–7” approach has been implemented effectively, with 100% of cases reported within 24 h, 88.9% cases investigated and confirmed within 3 days and 98.5% of foci responded to within 7 days. Although malaria elimination has been achieved in Yingjiang County, sustaining elimination and preventing the re-establishment of malaria require the continued strengthening of case detection, surveillance and response systems targeting the migrant population in border areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria, an infectious disease, has had the longest epidemic duration, and the broadest impact in the history of China1. It has been estimated that there were at least 30 million malaria cases annually before 19492. Following the implementation of a significant integrated malaria control and elimination programme for more than seven decades and specifically the “1–3–7” surveillance and response strategy that was developed and has been implemented since 20103,4, the disease burden has been greatly reduced2,5. Since 2017, no indigenous cases have been reported, achieving the standard of national malaria elimination6. Currently, China is ready for nationwide malaria elimination certification by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Yunnan Province borders Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam; the border extends 4060 km, touching 25 counties, with 17 border ports, and 643 border crossings. There is no natural barrier along the border7. According to malaria epidemiological data collected from surveillance systems in China's border areas, the population crossing the border and border residents of Yunnan Province, China, have a higher risk of malaria transmission8. Historically, malaria has been serious in Yunnan Province with more than 400 thousand malaria cases9,10. Since 2010, Yunnan has been the only province with Plasmodium falciparum transmission in China11. The last indigenous malaria case in China was reported in Yingjiang County of Yunnan Province in 20166; there have been no indigenous cases reported nationwide since, which allowed Yunnan Province to achieve verification of malaria elimination in June 2020.

A total of 18 counties in Yunnan Province sit on the China–Myanmar border. One of them, Yingjiang County, is located in western Yunnan Province and having a border length of 214.6 km; it borders Kachin State, Myanmar, in the western region10. The border areas on both sides are rural, hard-to-reach, poverty-stricken areas inhabited by minority nationalities12,13. The county has nine townships bordering Myanmar, five entry-exit highways, two provincial ports, four passages, and 33 boundary passages14. The climate, landscape and vectors of malaria on both sides of the border are similar12,13. In the last 10 years, the incidence of malaria in Yingjiang County has declined remarkably and this progress was made possible through greater access to effective malaria control tools. The last indigenous malaria case in China was caused by P. vivax infection in April 2016, located in Taiping Township of Yingjaing County6.

On the Myanmar side of the border with Yingjiang County, is Laiza, Kachin State (see Additional file 1), with a population of approximately 40,000; the area has been affected by malaria epidemics for several decades15. According to a malaria report from the China–Myanmar Joint Prevention and Control Information Exchange Mechanism, thousands of malaria cases were reported in Laiza in 2016 and 2017. However, the number of malaria cases has decreased dramatically in the last three years, supported by cross-border cooperation to achieve malaria elimination, timely case detection and appropriate treatment, and vector control and surveillance. The number of cases increased in 2020 as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Additional file 2). In September 2019, nearly 200 cases of vivax malaria were detected in a resettlement site containing 2500 residents on the Myanmar side of the border with Nabang Township of Yingjiang County (unpublished data).

Human population movement is one of the significant challenges in malaria control and elimination, especially in border areas. Population movement from high to low or non-malaria-endemic areas can result in imported infections, which may promote further transmission and threaten the success of previous elimination efforts16. Although malaria elimination has been achieved on the Chinese side of the border, the high risk of importation, introduction and re-establishment of malaria in the post-elimination stage should be of concern because of the migrant population crossing the border and the lack of barriers for malaria vectors17. Therefore, we conducted an epidemiological analysis of malaria in Yingjiang County to investigate the epidemiological characteristics of malaria and to identify the risk of re-establishment of malaria in this border area in the post-elimination stage.

Results

A total of 895 malaria cases were reported in the entire county in 2013–2019, including 45 indigenous cases and 850 imported cases. All cases were diagnosed by microscopy, and except 7, were also confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). There were no malaria-associated deaths reported during this period. The number of malaria cases was the lowest, at 72, in 2013 and reached a peak of 186 in 2016; then, it decreased to 92 in 2019. Malaria cases occurred predominantly in males (males 70.7%, n = 633; females 29.3%, n = 262), with a sex ratio of 2.42:1, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.2093). The majority of cases occurred in individuals aged 19–59 years (77.3%, 692/895). Most patients were outdoor workers (56.5%, 506/895), who have the highest risk of malaria infection (P < 0.0001); while indoor workers accounted for 27.8% (249/895) of the cases.

The proportion of indigenous malaria cases decreased from 25.0% (18/72) in 2013 to 0.05% (1/185) in 2016. The last indigenous malaria case reported in 2016 in Yunnan Province, was also the last in the whole country. Since 2017, no indigenous cases have been reported. P. vivax was the predominant malaria parasite in Yingjiang County. In 2013–2019, the proportion of P. vivax malaria was 96.6% (range: 89.73–100.0%). P. vivax infection was the most common cause of malaria in Yingjiang County, as well as in Yunnan Province. The annual reported number of P. falciparum cases was less than 10 from 2013–2019, and no P. falciparum cases was reported in 2019. One P. malariae infection and two mixed infections involving P. falciparum and P. vivax were reported (Table 1).

There are 15 townships in Yingjiang County and nine of which border Myanmar (Fig. 1). Most malaria cases were distributed in the southern and southwestern parts of the county. In 2013–2019, 54.0% (483/895) of the malaria cases were reported from Nabang Township, followed by Pingyuan Township, where the local government of Yingjiang County is located, with 15.5% (139/895). In 2013, a total of 72 malaria cases were reported in Yingjiang County; the cases were distributed in 14 out of 15 townships, while only six townships reported malaria cases in 2019. The number of reported malaria cases decreased slightly at the township level over time. In addition, the number of townships with indigenous cases decreased from eight in 2013, to six in 2014, three in 2015 and only one in 2016 (Fig. 1). Among all 45 indigenous cases, 55.6% occurred in Nabang Township, which also had the highest risk of imported malaria. The last indigenous malaria case was reported in Taiping Township in April 2016, which was also the last indigenous malaria case reported in the whole country. Since 2017, no indigenous cases have been reported in China, including these border counties.

The number of reported malaria cases in Yingjiang County displayed well-defined seasonality in 2013–2017, with one peak from May to July and a second smaller peak from November to the following January (Fig. 2). This seasonality was mainly associated with the geographical environment and meteorological factors that are strongly correlated with the abundance of Anopheles. There are only two seasons in the border area of Yingjiang County, the rainy season from May to September and the dry season from October to the following April. In 2018, the number of malaria cases reported from May to July decreased with a lower peak than that observed in previous years. In 2019, there were two similar peaks in June to July and in November (Fig. 2). The monthly trend was mainly caused by imported malaria cases among the migrant population not the natural dynamics of malaria transmission because only imported malaria cases have been reported since 2017.

The number of reported malaria cases in 15 townships and the proportion of indigenous and imported cases at the township level. Townships was colored based on the number of reported malaria cases in each year. The pie indicates the proportion of indigenous cases and imported cases in the townships with indigenous cases reported in 2013–2016. Maps were created by the first author (FH) using ArcGIS version 10.1, https://www.arcgis.com, and data of malaria cases were from publicly available sources (CIDRS, Malaria Elimination Programme, China).

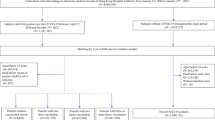

The “1–3–7” approach describes a system of activities dependent on timely diagnosis and response to malaria cases; the strategy includes strict hourly timelines to be followed. Within 24 h, any malaria case must be reported. By the end of day 3, the county’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) must confirm and investigate the case and determine whether there is a risk of spread. By the end of day 7, the county CDC must perform measures or interventions to prevent further spread by testing residents and family members in the community where the malaria case was identified. From 2013 to 2019, there were no delays in the reporting of malaria cases, and 895 malaria cases in Yingjiang County were reported within 1 day. In terms of case investigation and confirmation, an average of 88.9% (range: 64.2–100%) of cases were investigated within 3 days, and this indicator reached 100% in 2014, 2015, and 2016 (Fig. 3). The median case investigation durations from 2013 to 2019 were 0, 0, 1, 1, 33, 3, and 2 days, respectively, and the interquartile range (IQRs) of durations in each year are shown in Fig. 3. There were significant differences between years (P < 0.001). A total of 261 foci were identified during the study period, and 98.5% (256/261) were investigated and responded to within 7 days.

Of the 895 reported malaria cases, 97.1% (n = 869) were diagnosed in a health facility of a county CDC/hospital or township hospital (Table 1). The proportion of cases diagnosed at township hospitals increased slightly, while those diagnosed at county-level health facilities remained at a low level, indicating that relying on the capabilities of township hospitals is key.

Discussion

In 2010, China set an ambitious goal to eliminate malaria by 2020 and established a cooperative agreement among 13 ministries to eliminate malaria nationwide1. The “1–3–7” surveillance and response strategy, introduced after China launched the national malaria elimination programme, successfully reduced the number of indigenous cases of malaria to zero, where it has remained since 20176. Additionally, Yunnan Province, which shares borders with the malaria-endemic countries of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Vietnam, has achieved malaria elimination18,19.

Durations of case investigations and confirmations by county CDCs, 2013–2019. The median, range and upper and lower quartiles, and discrete values of the data were divided by discrete duration ranges. The figure was created in R using ggplot2 package (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2020, www.R-project.org; version 4.0.3).

Yingjiang County is one of 18 counties along the China–Myanmar border and has the highest risk of malaria transmission in Yunnan Province. According to the classification of the Malaria Elimination Action Plan (2010–2020), Yingjiang County was a Type I county (with indigenous cases reported for 3 years and an incidence rate ≥ 1/10,000) that was targeted for the implementation of key strategies to strengthen surveillance and reduce the incidence in the pre-elimination stage4. This study showed that malaria cases in Yingjiang County decreased significantly, with a total of 895 cases reported from 2013 to 2019, and no indigenous malaria cases reported on the Chinese side of the border in the past three years. The decline in indigenous cases on the Chinese side of the border was primarily attributed to the "1–3–7" surveillance and quick response strategy, which was not implemented on the Myanmar side. However, the reduction in imported cases in Yingjiang County was highly associated with malaria transmission in Kachin state, Myanmar, because 99% of imported malaria cases were imported from Myanmar. In the past several years, the malaria burden has been reduced in Kachin state due to cooperation between China and Myanmar regarding malaria elimination. However, the risk of malaria re-establishment in Chinese border areas should be of concern because malaria transmission still occurs on the Myanmar side13,20. Different cross-border activities may result in different temporal patterns of imported cases (e.g., the number of peak transmission seasons). For example, people engaged in frontier trade may frequently cross the border, while local farmers may go to Myanmar for logging or mining during the slack seasons in farming. In November 2019, the Hongbenghe Water Conservancy Construction Site, which was located at the China–Myanmar border in Taiping Township of Yingjiang County, was identified as an epidemic focus, and a total of 22 P. vivax malaria cases were identified. According to the case investigation, the source of infection was the bite of an Anopheles mosquito carrying malaria parasites that was transported from overseas; therefore, these cases were classified as imported malaria cases. This epidemic cluster caused another peak in monthly malaria cases in Yingjiang in 2019 (Fig. 2). Nabang Township, which reported more than half of the malaria cases in the county, borders Laiza in Kachin State of Myanmar. There is one provincial port and several boundary passages in this township and hundreds of migrants cross the border every day. According to local immigration records, approximately fifty thousand border crossings occur monthly at Nabang Port. This migrant population in the rural areas was less educated in preventive measures along with constantly low level of the community’s knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) regarding malaria. Moreover, some sections of the border comprise a stream that is only a few meters wide, and mosquitoes carrying parasites can cross the border easily. Similar geographical environments and meteorological factors along the border area play major roles in malaria transmission, mostly by mediating effects on both the mosquito vector and the development of the malaria parasite inside the mosquito vector23. The species of malaria vectors in Yunnan Province are the most diverse in China. According to a vector survey, a total of 11 Anopheles species have been identified in Nabang and Tongbiguan townships of Yingjiang County. Anopheles minimus is the primary malaria vector, followed by An. sinensis14,23,24.

P. vivax is the most geographically widespread parasite causing human malaria, and over 2.5 billion people are at risk of infection25,26. P. vivax malaria is mainly endemic in Southeast Asia and Central and South America. As reported by the WHO, more than half of P. vivax infections (53%) occur in the WHO South-East Asia region12,27. The proportion of vivax malaria cases in Yingjiang County increased from 2013 to 2019 and no falciparum malaria cases were reported in 2019, indicating that P. vivax was the predominant species on the Myanmar side and the rate of P. falciparum infection in Myanmar was very low because more than 95% of the imported cases were from Myanmar. This change was similar to that in other countries in the Greater Mekong sub-region28,29. The epidemiology of vivax malaria in this region is highly heterogeneous and P. vivax has become a major challenge to malaria elimination in this region30,31.

China’s “1–3–7” surveillance and response strategy was developed and used for malaria elimination nationwide2,3. In this study, we analysed the three indicators included in the “1–3–7” approach in Yingjiang County. All malaria cases were reported to the CIDRS within 24 h, indicating that the web-based case reporting system is sensitive, as it allowed a prompt response, even in township hospitals. The proportion of case investigations and confirmations completed within 3 days was 88.9%, compared with only 64.2% in 2017 (Fig. 3). The main reasons for the lower rate were that some patients were located in very remote and hard-to-reach areas; therefore, it took the county CDC longer than usual to complete the case investigation and confirmation. During the study period, 98.5% (256/261) of the foci were investigated and responded to within 7 days. The “1–3–7” approach was implemented effectively in Yingjiang County at the county level, similar to other counties32. This strategy is not only the technical specification for malaria elimination in China, but it has been adopted by the WHO, and is included in the Malaria surveillance monitoring & evaluation, a reference manual33. Recently, the “1–3–7” approach has been popularized and applied in many countries and regions worldwide and has made great contributions in the progress toward global malaria elimination34,35,36.

Although great achievements have been made in reducing the overall number of cases of malaria and eliminating indigenous cases in China, the elimination campaign faces challenges in areas near international borders22,37. The specific environmental, administrative, anthropological, and geographic characteristics of border areas have a unique impact on the epidemiology of malaria. Cross-border malaria is difficult to manage because of political, economic and geographic constraints38,39. In addition, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected the availability of key malaria control interventions and may cause malaria-associated morbidity and mortality to increase in the future40,41.

Conclusion

Substantial gains have been made in reducing the number of malaria cases and eliminating indigenous malaria in Yingjiang County. Sustaining elimination and preventing the re-establishment of malaria require the strengthening of case detection, surveillance and response system targeting migrant populations in border areas.

Methods

Description of the study area

Yingjiang County is located in western Yunnan Province (97°31′–98°16′N, 24°24′–25°20′E). It shares a long border with Kachin State, Myanmar and had the highest risk of malaria transmission in Yunnan Province (Fig. 4). The land area of Yingjiang County is 4429 km2, with a local population of 316,990 people. Yingjiang County is mountainous with several alluvial plains. The county has various climate types, ranging from tropical to subtropical and temperate zones, and has an average annual temperature of 22.7 °C and annual rainfall of 2.65 m. Intact forests exist in the mountains above 2000 m. The elevation varies from 210 to 3404 m. The county is within a very active seismic zone and was affected by violent earthquakes in 2008, 2009 and 2011. Migration, plantation and logging activities are frequent along the border42. An. sinensis and An. minimus are reported to be the dominant vectors for malaria parasites23,43.

Location of Yingjiang County and the townships along the China–Myanmar border. A total of 15 townships were included in Yingjiang County, nine of which borders Myanmar shown with light red color. Maps were created by the first author (FH) working with ArcGIS version 10.1, https://www.arcgis.com.

Data collection

Malaria case data and demographic information, including sex, age, occupation, residential address, type of disease, date of onset, and date of confirmation were collected from the web-based Chinese Infectious Disease Report System (CIDRS) from 2013 to 201944,45. Malaria cases were classified according to the criteria of the national guidelines of China as laboratory-confirmed malaria, which referred to patients with a positive result on one type of laboratory test, including microscopy, a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), or PCR, or clinically diagnosed malaria, which referred to patients with malaria–like signs and symptoms but without the detection of parasites on blood examination46. Malaria case data from 15 townships were extracted to map the malaria distribution at the township level. In addition, according to the Technical Program for Malaria Elimination in China47, indigenous malaria was defined as malaria infection obtained from within the province in which the diagnosis was made, while imported malaria was defined as malaria whose origin can be traced to a transmission area outside the province in which the malaria diagnosis of malaria was made; moreover, the following criteria for imported malaria was also applied: the patient has received a malaria diagnosis; the patient had a travel history to a malaria-endemic area outside China during the malaria transmission season; and the onset time for malaria was less than 1 month after returning to China during the local transmission season.

Data analysis

R software (Version 4.0.3; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2020; www.R-project.org)48 and SAS software (SAS Institute Inc, Version 9.2, Cary, NC, USA) were used for data processing and statistical analysis. The chi-squared test was used to evaluate differences among the different sub-groups; Fisher's exact test was used if 25% of the cells had expected counts less than 5. Maps were created using ArcGIS 10.1 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc, Redlands, CA, USA). The indicators used to evaluate the implementation of the “1–3–7” approach were determined from the individual case reports downloaded from the CIDRS. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethical Review Committee of National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, No. 2019008.

Data availability

The data used in this study is publicly available.

References

Zhou, X. N. et al. Feasibility and roadmap analysis for malaria elimination in China. Adv. Parasitol. 86, 21–46 (2014).

Feng, X. et al. The contributions and achievements on malaria control and forthcoming elimination in China over the past 70 years by NIPD-CTDR. Adv. Parasitol. 110, 63–105 (2020).

Feng, J. et al. Towards malaria elimination: monitoring and evaluation of the “1–3–7” approach at the China–Myanmar border. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95, 806–810 (2016).

Hu, T. et al. Shrinking the malaria map in China: measuring the progress of the National Malaria Elimination Programme. Infect. Dis. Poverty 5, 52 (2016).

Yang, W. Z. & Zhou, X. N. New challenges of malaria elimination in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 50, 289–291 (2016).

Feng, J. et al. Ready for malaria elimination: zero indigenous case reported in the People’s Republic of China. Malar. J. 17, 315 (2018).

Lo, E. et al. Frequent Spread of Plasmodium vivax malaria maintains high genetic diversity at the Myanmar-China border, without distance and landscape barriers. J. Infect. Dis. 216, 1254–1263 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Risk assessment of malaria in land border regions of China in the context of malaria elimination. Malar. J. 15, 546 (2016).

Xia, Z. G. et al. Lessons from malaria control to elimination: case study in Hainan and Yunnan provinces. Adv. Parasitol. 86, 47–79 (2014).

Xu, J. & Liu, H. The challenges of malaria elimination in Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China. . Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 43, 819–824 (2012).

Zhou, S. S., Wang, Y. & Li, Y. Malaria situation in the People’s Republic of China in 2010. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 29, 401–403 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Effectiveness and impact of the cross-border healthcare model as implemented by non-governmental organizations: case study of the malaria control programs by health poverty action on the China–Myanmar border. Infect. Dis. Poverty 5, 80 (2016).

Huang, F. et al. From control to elimination: a spatial-temporal analysis of malaria along the China–Myanmar border. Infect Dis Poverty 9, 158 (2020).

Zhang, C. L. et al. Evaluation on malaria hotspots in Yingjiang County of the China–Myanmar border area in 2015. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 34, 430–434 (2016).

Liu, H., Xu, J. W. & Bi, Y. Malaria burden and treatment targets in Kachin Special Region II, Myanmar from 2008 to 2016: A retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE 13, e0195032 (2018).

Martens, P. & Hall, L. Malaria on the move: human population movement and malaria transmission. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6, 103–109 (2000).

WHO. China’s road to malaria elimination. (2019).

Wei, C. et al. Epidemic situation of malaria in Yunnan Province from 2014 to 2019. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi 32, 483–488 (2020).

Routledge, I. et al. Tracking progress towards malaria elimination in China: Individual-level estimates of transmission and its spatiotemporal variation using a diffusion network approach. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1007707 (2020).

Zhao, X. et al. Malaria risk map using spatial multi-criteria decision analysis along Yunnan border during the pre-elimination period. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103, 793–809 (2020).

Xu, J. W. & Liu, H. The relationship of malaria between Chinese side and Myanmar’s five special regions along China–Myanmar border: a linear regression analysis. Malar. J. 15, 368 (2016).

Shi, B. et al. Risk assessment of malaria transmission at the border area of China and Myanmar. Infect. Dis. Poverty 6, 108 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Receptivity to malaria in the China–Myanmar border in Yingjiang County, Yunnan Province China. Malar. J. 16, 478 (2017).

Zhang, S. S. et al. Monitoring of malaria vectors at the China–Myanmar border while approaching malaria elimination. Parasit. Vectors 11, 511 (2018).

Howes, R. E. et al. Global epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95, 15–34 (2016).

Mendis, K., Sina, B. J., Marchesini, P. & Carter, R. The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 64, 97–106 (2001).

WHO. World malaria report 2019. (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Dynamics of Plasmodium vivax populations in border areas of the Greater Mekong sub-region during malaria elimination. Malar J 19, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03221-9 (2020).

Kaehler, N. et al. Prospects and strategies for malaria elimination in the Greater Mekong Sub-region: a qualitative study. Malar. J. 18, 203 (2019).

Chen, S. B. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of a Plasmodium vivax clinical isolate exhibits geographical characteristics and high genetic variation in China–Myanmar border area. BMC Genomics 18, 131 (2017).

Cui, L. et al. Malaria in the Greater Mekong Subregion: heterogeneity and complexity. Acta. Trop. 121, 227–239 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. Adapting the local response for malaria elimination through evaluation of the 1-3-7 system performance in the China–Myanmar border region. Malar. J. 16, 54 (2017).

WHO. Malaria surveillance, monitoring & evaluation: a reference manual. (2018).

Aung, P. P. et al. Challenges in early phase of implementing the 1-3-7 surveillance and response approach in malaria elimination setting: A field study from Myanmar. Infect. Dis. Poverty 9, 18 (2020).

Kheang, S. T. et al. Malaria elimination using the 1-3-7 approach: lessons from Sampov Loun Cambodia. BMC Public Health 20, 544 (2020).

Lertpiriyasuwat, C. et al. Implementation and success factors from Thailand’s 1–3–7 surveillance strategy for malaria elimination. Malar. J. 20, 201 (2021).

Arisco, N. J., Peterka, C. & Castro, M. C. Cross-border malaria in Northern Brazil. Malar. J. 20, 135 (2021).

Parker, D. M. et al. Microgeography and molecular epidemiology of malaria at the Thailand-Myanmar border in the malaria pre-elimination phase. Malar. J. 14, 198 (2015).

Carrara, V. I. et al. Malaria burden and artemisinin resistance in the mobile and migrant population on the Thai-Myanmar border, 1999–2011: an observational study. PLoS Med. 10, e1001398 (2013).

Weiss, D. J. et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on malaria intervention coverage, morbidity, and mortality in Africa: a geospatial modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 59–69 (2021).

Rogerson, S. J. et al. Identifying and combating the impacts of COVID-19 on malaria. BMC Med. 18, 239 (2020).

Xu, J. W., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Guo, X. R. & Wang, J. Z. Risk factors for border malaria in a malaria elimination setting: a retrospective case-control study in Yunnan, China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92, 546–551 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Anopheles vectors in mainland China while approaching malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 33, 889–900 (2017).

Bai, B. K., Xu, Z. & Shen, H. H. Infectious disease surveillance in China. J. Infect. 71, 698–700 (2015).

Yan, W. R. et al. Establishing a web-based integrated surveillance system for early detection of infectious disease epidemic in rural China: a field experimental study. BMC Med. Inform Decis. Mak. 12, 4 (2012).

National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Diagnosis of malaria (WS259–2015), Beijing (2016).

National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Technical Programme for Malaria Elimination, Beijing (2011).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staffs for their efforts and assistances in data collection in Yingjiang County. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (No. 18ZR1443400), the National Important Scientific & Technological Project 2018ZX10101002–002), the Fifth Round of Three–Year Public Health Action Plan of Shanghai (No. GWV–10.1–XK13), the Forge Ahead Together for Elimination Towards Malaria free China–Myanmar border and National Malaria Elimination Program of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H., X.N.Z. conceived and designed the study; S.G.L., P.T., X.R.G. and H.N.Z. contributed to malaria data collection; H.N.Z., S.S.Z. and Z.G.X. contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript; F.H and P.T. carried out the data analysis. F.H. drafted the main manuscript text and prepared Figs. 1, 3 and 4. S.G.L and P.T. prepared Fig. 2 and Table 1. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, F., Li, SG., Tian, P. et al. A retrospective analysis of malaria epidemiological characteristics in Yingjiang County on the China–Myanmar border. Sci Rep 11, 14129 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93734-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93734-3

This article is cited by

-

Prompt and precise identification of various sources of infection in response to the prevention of malaria re-establishment in China

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.