Abstract

A novel magnetic field sensor is proposed based on the combination of in-line tapered photonic crystal fibre (PCF) Mach–Zehnder interferometer and magnetic nanoparticles. The sensor is theoretically investigated and experimentally realized. The effect of the mechanical strain and the magnetic field on the sensitivity of the sensor is studied. It is found that the proposed sensor shows a wavelength-sensitivity of \(-\,0.072\,\text {nm/mT}\) and a strain-sensitivity of \(1\,\text {pm/}\upmu \,\epsilon \,\). To evaluate the effect of the magnetic nanoparticles on the output light intensity, the sensitivity response of the device has been measured under different magnetic field strengths for different length scales. The experimental results show refractive index changes of the magnetic nanoparticles-infiltrated PCF—acting as fibre cladding—under the applied magnetic field leads to variations of the interferometric output. The sensitivity of magnetic field measurement with the sensor with \(30\,\text {mm}\) and \(40\,\text {mm}\) PCF could reach up to \(0.021\,\text {dB/mT}\) and \(0.017\,\text {dB/mT}\), respectively. The results show a very good linear response that is an essential requirement for the practical sensors. The proposed magnetic field sensor finds applications in various areas, such as optical sensing, military, power industry, and tunable photonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of nanotechnology, a new class of smart nano-materials emerges as a promising platform for novel optoelectronic devices. In particular, ferrofluids (FFs) or magnetic fluids, which are stable colloidal solutions containing surfactant-coated magnetic nanoparticles dispersed in an appropriate liquid, possess both the magnetism of magnetic nanoparticles and fluidity of liquid materials1,2. The unique properties of FFs, such as optical anisotropy and birefringence, the Faraday effect, tunable refractive index, and field-dependent transmission, can be tuned by external magnetic fields. Due to these outstanding magneto-optical properties, FFs have been used to design unique photonic devices, such as optical switches3, optical modulators4, tunable optical filters5, optical fibre gratings6, and sensors7,8.

Photonic crystal fibres (PCFs), first invented and demonstrated in 19969, have peculiar properties owing to the complex pattern of air-holes in their cross-section that runs within the fibre. The intrinsic air-holes of the PCF cladding that can be infiltrated by gases, dyes, liquids, or low-viscosity polymers10,11, establish an adaptable platform for developing tunable optofluidic devices. For example, a tunable electro-optical modulator has been realized by filling one air-hole of PCF with liquid-crystal12. Also, it is shown that the infiltration of optofluids into the first ring of the PCF cladding may lead to dispersion engineering for tunable wavelength conversion13. The temperature and refractive index sensors based on in-line Fabry–Pérot interferometer in PCF were reported14. It is shown that the sensitivity can be increased via optimizing the length of PCF. Tapered PCF was employed in an interferometer structure to construct a miniaturized refractive index sensor15. Using the advantages of polarization-maintaining PCFs, a magnetic field sensor with the sensitivity of \(242\,\text { pm/mT}\) is reported16.

Accurate measurements of the magnetic field are of scientific and industrial importance for many applications such as medicine, military, vehicle monitoring, and geological prospecting. In the last few decades, various types of magnetic field sensor are proposed and realized, for example, based on side-polished fibre17, cascaded microfibre coupler18, fibre ring cavity laser19, tapered microfibre20, and birefringence in liquid-core optical waveguide21. Recently, the plasma resonance effect is used in a twin-core PCF to realise the simultaneous measurement of magnetic field and temperature22. Also, the magnetic field sensitivity and resolution of a surface Plasmon resonance (SPR)-based PCF magnetic field sensor is theoretically analysed while optimizing the sensor structure parameters23. An innovative sensor based on tapered few-mode fibre (TFMF) and Magnetic fluid encapsulated outside the TFMF is proposed to detect magnetic fields in different directions24. The sensitivity response of the magnetic field sensors had reported in terms of changes in wavelength shift or output intensity. Among different kinds of magnetic field sensors, fibre-optic interferometric sensors are the ones that have attracted a great deal of research attention due to the compactness, immunity to electromagnetic interference, low-cost and easy fabrication. A fibre-optic interferometer operates based on the interference between two propagating beams either in two different adjacent fibres or through different optical paths in a single optical fibre. Especially, the unique properties of PCFs make them appealing for optical sensing. PCF-based interferometric sensors include Fabry–Pérot interferometer, Mach–Zehnder interferometer, Michelson interferometer, and Sagnac interferometer25,26,27. In particular, to implement an in-line Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI), a beam splitter, and a beam combiner are needed to guide light in the arms of the interferometer28. Generally, an in-line fibre-based interferometer can be realized via core misalignment and collapsing methods. In these methods, a more complicated interference pattern is expected due to the possibility of exciting the high-order cladding modes29.

In this work, we report a low-cost highly-sensitive magnetic field sensor using the advantages of an in-line MZI in an FF-assisted tapered PCF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the magnetic sensitivity of a tapered PCF-MZI is reported. The sensor behavior has been investigated both theoretically and experimentally. In the first step, the \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) magnetic nanoparticles are synthesized using a reverse co-precipitation method. Then, by accurately injecting a small amount of the FF into two innermost air-holes of PCF and exposing the PCF-MZI to the magnetic field, the refractive index variations are verified. Thus, a magnetically-tunable refractive index can lead to changes in output light. The PCF is then tapered using a custom-made tapering machine. It is found that the proposed sensor shows a strain sensitivity of \(1\,\text {pm/}\,\upmu \,\,\varepsilon \,\). For a given length of tapered-PCF, it is shown that the sensitivity of the sensor depends on the applied magnetic field. It is found that the sensitivity is strongly dependent on the length of the MZI. We have shown that the magnetic field of few mT can be detected with higher sensitivity of \(0.024\,\text {dB/mT}\). Compared with other magnetic field sensors, the proposed PCF-MZI sensor has many features, such as a simple compact structure, high sensitivity, and stability. Moreover, since splicing a section of a PCF in between two common single-mode fibres (SMFs) is not complex, the fabrication is simple and cost-effective, making it a good candidate for multi-parameter measurements. The results show a very good linear response that is an essential requirement for the practical sensors.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) magnetic nanoparticle

Iron oxide (\(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\)) magnetic nanoparticles of average size \(\sim \)10–12 nm were synthesized using the reverse co-precipitation method16, which is an efficient low-cost method. Note that in the normal co-precipitation method, the precipitating agent is added to the cation solution that causes the pH value to increase from acidic state to basic state, whereas in the reverse co-precipitation this addition is inversed30. All chemicals used in the experiment were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. In the synthesis, the base solution is prepared by diluting 30% ammonia (\(\text {N}{{\text {H}}_{\text {4}}}\text {OH}\)) with adding doubled distilled water (DDW) (3:2 ratio) in a three-neck flask. The solution is mechanically stirred and heated to \(80\,^{\circ }\text {C}\) under argon. Then, Fe salt solution is prepared by dissolving ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (\(\text {FeS}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\cdot \text {7}{{\text {H}}_{\text {2}}}\text {O}\)) and Iron(III) nitrate \(\text {Fe(N}{{\text {O}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {)}}_{\text {3}}}\) (with 1:2 molar ratio) in \(200\,\text {ml}\) DDW. While keeping the temperature constant at \(80\,^{\circ }\text {C}\), these solutions were mixed under vigorous stirring for 30 min under argon. The final solution was turned from brown to black indicating the nucleation and growth of magnetic nanoparticles. After rapidly cooled down to room temperature using an ice bath, the solution is carefully injected inside the PCF air-holes using a syringe with a 0.5 mm diameter needle. The FF-infiltrated PCF has been left for \(24\,\text {h}\) before any further steps.

Fabrication and sensing principle

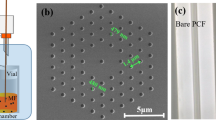

The experimental setup of the magnetic field sensor is shown in Fig. 1a. The sensor structure consists of a broadband light source (BLS) (Thorlabs, SLS202(/M)), a sensing PCF-based interferometer, an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) (Yokogawa, AQ6370D). As shown in Fig. 1b, to implement the in-line PCF-MZI, a small section of PCF is spliced between a lead-in and a lead-out standard SMF-28 fibre. The PCF used in this experiment is a large-mode-area PCF (Thorlabs, LMA-35) which has a core diameter of \(35\, \upmu \text { m}\), outer cladding diameter of \(335\,\upmu \text { m}\), \(\Lambda =23.15\,\,\upmu \text { m}\), \(d/\Lambda =0.5\) and the attenuation of \(<0.01\,\text {dB/m}\) @\(1550\,\text {nm}\). The fusion splicing is performed with a commercial fusion splicing machine (Ericsson FSU-955). The length of the collapsed zones is carefully controlled by changing the intensity and the duration of arc discharge. In the fabricated PCF-MZI, one propagating beam is referred to as the sensing arm and the other one is called the reference arm26. Even though the physical length of the two arms is identical, the interference signal can be detected. Physically, this behavior can be understood from the fact that since the effective indices of the core and cladding are not identical, there will be an optical path difference between the arms of the interferometer. In this case, the phase velocity of the reference and sensing arm is different.

Since the MZI-based sensors are very sensitive to fibre bending, the device was firmly kept constant with the aid of fibre holders. To apply the axial strain, the two sides of inline PCF-MZI were clamped to two stages: a fibre holder of the micro-positioner stage and a fibre holder of the fixed stage. The PCF-MZI is then placed between two poles of an electromagnet, which generates a uniform magnetic field. The intensity of the magnetic field can be adjusted by tuning the power supply. The magnetic field direction is perpendicular to the propagation of light and the optical fibre axis. The operating principle of the sensor is as follows: Light from the BLS is coupled into the lead-in SMF and enters the collapsed zone of the PCF. In this region, light promptly begins to diffract, leading to mode broadening. Then it passes through the PCF region, recombines at the second collapsed zone. The output light is monitored and analyzed by the OSA with the wavelength resolution 0.02 nm. The occurrence of total internal reflection and more importantly the interference between core and cladding modes is dependent on the axial strain, the strength of the magnetic field, and the length of the MZI.

The device can be modeled using a core and cladding mode interference equation given by29

where \({{I}_{\text {out}}}\) is the intensity of the total interference signal, \({{I}_{\text {1}}}\) and \({{I}_{\text {2}}}\) are the intensities of light propagating in the fibre core and cladding. The phase difference between the core and cladding modes, \(\Delta \Phi \), depends on the effective refractive index difference and the physical length of the interferometer, and can be expressed as

where \(\Delta {{n}_{\text {eff}}}=n_{\text {eff}}^{\text {core}}-n_{\text {eff}}^{\text {clad}}\) is the effective refractive index difference between the core and cladding, L is the length of the interferometer, and \(\lambda \) is the central wavelength of the BLS. As a result of the magnetic field dependence of the FF-filled cladding refractive index, this phase difference also depends on the applied magnetic field.

The minimum in the intensity of the output spectrum will occur when

where \(\text {m}\) is the interference order. In the absence of an external magnetic field, the coupling length, \(\zeta \), can be obtained by using the propagation constants of fundamental and cladding modes \({{\beta }_{\text {core}}}\) and \({{\beta }_{\text {clad}}}\) as \(\zeta =2\pi /({{\beta }_{\text {core}}}-{{\beta }_{\text {clad}}})=\lambda /({{n}_{\text {core}}}-{{n}_{\text {clad}}})\)31. The low difference between refractive indices is responsible for the high coupling length and also responsible for high sensitivity32.

Experimental results and discussion

In this section, the main results are presented and the effect of magnetic field and strain on the intensity of output light is investigated. The FF used in our study is \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) nanoparticles synthesized by the chemical reverse co-precipitation method. The crystalline nature of the synthesized magnetic nanoparticles is characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, shown in Fig. 2a. The observed diffraction peaks at \(2\theta =\,{{30.35}^{\circ }},\,{{35.63}^{\circ }},\,{{37.07}^{\circ }}\text {,}\,{{43.40}^{\circ }},\,{{53.87}^{\circ }},\,{{57.41}^{\circ }}\) and \({{63.17}^{\circ }}\) corresponds to (hkl) = (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), and (440) planes of \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) in cubic phase, which is in a good agreement with the literature Joint Committee on. Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS card, No. 19-0629). The average size of crystallite domains D calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation \(D=K\lambda /(\beta \cos \theta )\) is 11.56 nm that confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Here, \(K=0.9\) is a dimensionless shape factor, \(\lambda =0.15406\,\text {nm}\) is the X-ray wavelength, \(\beta \) is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity (FWHM), and \(\theta \) is the Bragg angle. Figure 2b shows a TEM image of synthesized \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) in which most of the nanoparticles are spherical with an average diameter of \(\sim \)10–12 nm.

Figure 2c shows the magnetization curve for as-synthesized \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) magnetic nanoparticles. The saturation magnetization measured at \(300\,^{\circ }\text {K}\) is about \(65\,\text {emu/g}\), exhibiting conformity with previous works33,34. It is known that the optical response of the FFs depends on temperature and magnetic field intensity and simultaneous changes in these parameters cause an inaccurate magnetic field sensing35. The relationship between refractive index and magnetic field for \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) FF has been extensively reported in the literature36,37, and it is found that the refractive index of the magnetic fluid increases with enhancing field strength38. Figure 2d shows the magnetic field dependence of the FF refractive index \({{n}_{FF}}\). The refractive index is measured via the direct contact angle method39. It is observed that \({{n}_{FF}}\) is constant until the applied magnetic field reaches a critical value \({{H}_{c}}=8\,\text {mT}\). Beyond \({{H}_{c}}\), the \({{n}_{FF}}\) increases until it reaches saturation. Therefore, the operating range of the sensor is in the range of \(8\,\text {mT}\) to \(140\,\text {mT}\). Under a constant temperature T, \({{n}_{FF}}\) can be obtained from the Langevin function40,41.

where \({{n}_{i}}\)(= 1.4254 here) is the refractive index of the FFs under magnetic fields lower than \({{H}_{c}}\), \({{n}_{f}}\)(= 1.4469) is the saturated value of the FF refractive index, and \(\alpha \) is a fitting coefficient. Note that \({{H}_{c}}\) depends on the concentration of FFs and the type of carrier liquid40.

Prior to the experimental studies, the numerical simulation carried out with the PCF structural parameters as radius of holes of \(5.8\,\upmu \text { m}\), the lattice constant of \(23.15\,\upmu \text { m}\), the core diameter of \(35\,\upmu \text { m}\), and the outer cladding diameter of \(335\,\upmu \text { m}\). The mode field diameter of LMA-35 PCF is \(26.0\pm 2.5\,\,\upmu \text { m}\), which is almost three times that of a SMF. Figure 3a shows the fundamental core mode of the PCF. The simulation is carried out using commercial software (ANSYS Lumerical 2020). The transmission spectrum of the PCF-MZI in the absence of an external magnetic field is presented in Fig. 3b. It can be observed that the results obtained from the experiment show a very good agreement with the theoretical result. The interferometry spectrum of the PCF-MZI with increasing magnetic field from 0 to \(30\,\text {mT}\) is experimentally obtained and presented in Fig. 3c. During the experiment, both ends of the magnetic field sensor were held straight to prevent the effect of strain variations. It can be realized that the intensity dips are narrow and interference dips shift towards short wavelengths (i.e. dips experience blue-shift), which is consistent with the reduction of \(\Delta {{n}_{\text {eff}}}\) by increasing magnetic field [see Eq. (3)]. Sensitivity of the sensor can be calculated by \(S={\Delta \lambda }/{\Delta H}\;\) (nm/mT), where \(\Delta \lambda \) is the shift of dip wavelength and \(\Delta H\) is the variation of magnetic field intensity. As shown in Fig. 3d, when the magnetic field intensity is less than \(140\,\text {mT}\), the sensitivity behavior of the sensor is primarily a linear relationship. In the linear regime, the sensitivity of the magnetic field sensor is found to be \(-0.072\,\text {nm/mT}\). Beyond \(140\,\text {mT}\), the wavelength shift tends to be constant, as the refractive index of FF gets saturated.

When the involved modes propagate in the PCF, the effective refractive index difference between the core mode and corresponding cladding mode results in an optical phase difference (OPD). Due to the OPD in the sensing and reference arm, interference occurs between the light beams in these arms. Filling the FF solution into the air hole of the PCF reduces the effective refractive index difference between the cladding and the core of the PCF, thereby increasing the sensitivity of sensing structure to the external environment42. As mentioned before, the proposed sensor operates based on light intensity modulation. It is well-known that the refractive index of PCF background material (i.e. Corning 7980 fused Silica) is not sensitive to the magnetic field. However, the randomly homogenous structure of FFs changes under an external magnetic field. Therefore, field-dependent rearrangement of \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) nanoparticles leads to the refractive index variation of the FF, accordingly, light modulation is possible. The intensity dips can also be shifted by changing the length of PCF (L). In order to study the dependence of the Dip A intensity on the physical length of PCF-MZI, two interferometers with different PCF lengths were fabricated. The effect of magnetic field strength on the output light intensity is investigated by gradually increasing the applied magnetic field from 0 to \(140 \,\text {mT}\). Figure 4 shows the variation of intensity dip as a function of magnetic field strength. The magnetic field dependence of the intensity dip is obtained for two different lengths of PCF-MZI. It is found that the dip intensity of output light is an ascending function of the applied magnetic field. The experimental results show that the sensitivity of magnetic field measurement could reach \(0.021\,\text {dB/mT}\), and \(0.017\,\text {dB/mT}\) for the PCF-MZI lengths of \(L=30\,\text {mm}\) and \(L=40\,\text {mm}\), respectively. From Fig. 4a, it can be predicted that the intensity dip of output light changes slightly for the magnetic field below \(8\,\text {mT}\), which is in agreement with previous results43. It is worth mentioning that the intensity of the output light tends to be constant for the magnetic strength range beyond the saturation magnetization of \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) magnetic nanoparticles, which is not investigated in this study.

In the next step, to investigate the wavelength-strain sensitivity of the sensor, the two sides of the inline PCF-MZI were attached to two stages, a moving stage and a fixed one. The axial movement of the micro-positioner stage causes an axial strain on the tapered region along with other PCF section. This leads to a wavelength shift of the interference pattern. Figure 5a shows the axial strain response of the in-line PCF-MZI sensor. From the transmission spectrum of the PCF-MZI, it can be observed that the intensity dip is blue-shifted without a significant change in its shape as the axial strain is increased from 0 to \(1200\,\,\upmu \text { }\varepsilon \,\). The changes in fibre dimensions and the photo-elastic effect of the fibre due to the applied axial strain lead to this shift in the interferometric spectrum. At a constant temperature, the wavelength shift due to the strain can be expressed as \(\Delta \lambda /\lambda =-\left( 1+2\nu +{{p}_{e}} \right) \varepsilon \), where \(\nu \) is the Poisson ratio of the fibre, \({{p}_{e}}\) is the effective strain-optic coefficient, and \(\varepsilon =\Delta L/L\) is the axial strain applied on the fibre44. The relationship between the applied strain and the dip wavelength is presented in Fig. 5b and the strain sensitivity is found to be \(1\,\text { pm/}\upmu \,\varepsilon \,\). A fitting curve of the experimental data shows that the wavelength shift is linear with the correlation factor of \({{\text {R}}^{\text {2}}}=0.99\). To find out the number and power distribution of the interfering modes, the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of transmission spectrum is taken to obtain its corresponding spatial frequency spectra. Figure 5c shows that only one cladding mode is dominantly excited, while the other cladding modes are very weak. It can be observed that applying the strain on the sensor changes the interferometer length, leading to the increment of the power of the cladding modes.

Table 1 provides a brief review of the sensitivities of PCF-based magnetic field sensors. Compared to the previous intensity-modulated magnetic field sensors, the proposed sensor has a higher sensitivity for low magnetic field intensity measurement. At the same time, the sensor exhibits linear response that is an essential requisite for the practical sensors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a highly-sensitive magnetic field sensor based on the combination of an in-line PCF-MZI with the characteristics of the magnetic nanoparticles. First, the \(\text {F}{{\text {e}}_{\text {3}}}{{\text {O}}_{\text {4}}}\) ferrofluid is synthesized using the reverse co-precipitation method. The FF response to the magnetic field intensity exhibits a Langevin function. By infiltrating air-holes of the PCF with FF and fusion splicing with standard SMFs, in-line PCF-MZI is realized. The effect of the magnetic field and the mechanical strain on the sensitivity of the sensor is studied. It is found that the proposed sensor shows a wavelength-sensitivity of \(-0.072\,\text {nm/mT}\) and a strain-sensitivity of \(1\,\text {pm/}\upmu \,\varepsilon \,\). The experimental results show refractive index changes of the FF-filled PCF - acting as fibre cladding - under the applied magnetic field leads to variations of the interferometric output. The sensitivity of magnetic field measurement could reach up to \(0.017 \,\text {dB/mT}\). The results show a very good linear response that is an essential requirement for the practical sensors. The proposed magnetic field sensor finds applications in various areas, such as optical sensing, military, power industry, and tunable photonic devices.

References

Gubin, S. P., Koksharov, Y. A., Khomutov, G. B. & Yurkov, G. Y. Magnetic nanoparticles: preparation, structure and properties. Russian Chem. Rev. 74, 489–520. https://doi.org/10.1070/RC2005v074n06ABEH000897 (2005).

Luo, L., Pu, S., Dong, S. & Tang, J. Fiber-optic magnetic field sensor using magnetic fluid as the cladding. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 236, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2015.10.034 (2015).

Horng, H. E. et al. Tunable optical switch using magnetic fluids. Appli. Phys. Lett. 85, 5592–5594. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1833564 (2004).

Horng, H. E. et al. Designing optical-fiber modulators by using magnetic fluids. Opt. Lett. 30, 543–545. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.30.000543 (2005).

Liu, T. et al. Tunable magneto-optical wavelength filter of long-period fiber grating with magnetic fluids. Appli. Phys. Lett. 91, 121116. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2787970 (2007).

Candiani, A., Margulis, W., Sterner, C., Konstantaki, M. & Pissadakis, S. Phase-shifted bragg microstructured optical fiber gratings utilizing infiltrated ferrofluids. Opt. Lett. 36, 2548–2550. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.36.002548 (2011).

Zhao, Y., Liu, X., Lv, R.-Q., Zhang, Y.-N. & Wang, Q. Review on optical fiber sensors based on the refractive index tunability of ferrofluid. J. Lightw. Technol. 35, 3406–3412 (2017).

Cennamo, N. et al. A magnetic field sensor based on spr-pof platforms and ferrofluids. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Measur. 70, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2020.3035114 (2021).

Knight, J. C., Birks, T. A., Russell, P. S. J. & Atkin, D. M. All-silica single-mode optical fiber with photonic crystal cladding. Opt. Lett. 21, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.21.001547 (1996).

Martelli, C. et al. Evanescent-field spectroscopy using structured optical fibers: Detection of charge-transfer at the porphyrin-silica interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2925–2933. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja8081473 (2009) (PMID: 19203267).

Markos, C., Vlachos, K. & Kakarantzas, G. Bending loss and thermo-optic effect of a hybrid pdms/silica photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Express 18, 24344–24351. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.18.024344 (2010).

Huang, Y. et al. Tunable electro-optical modulator based on a photonic crystal fiber selectively filled with liquid crystal. J. Lightw. Technol. 37, 1903–1908. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2019.2894910 (2019).

Pakarzadeh, H., Derakhshan, R. & Hosseinabadi, S. Tunable wavelength conversion based on optofluidic infiltrated photonic crystal fibers. J. Nonlinear Opti. Phys. Mater. 28, 1950002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218863519500024 (2019).

Dash, J. N. & Jha, R. Inline microcavity-based pcf interferometer for refractive index and temperature sensing. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 27, 1325–1328. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2015.2421308 (2015).

Ahmed, F., Ahsani, V., Melo, L., Wild, P. & Jun, M. B. G. Miniaturized tapered photonic crystal fiber Mach–Zehnder interferometer for enhanced refractive index sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 8761–8766. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2016.2566663 (2016).

Thakur, H. V., Nalawade, S. M., Gupta, S., Kitture, R. & Kale, S. N. Photonic crystal fiber injected with fe3o4 nanofluid for magnetic field detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 161101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3651490 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. All-fiber-optic vector magnetic field sensor based on side-polished fiber and magnetic fluid. Opt. Express 27, 35182–35188. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.035182 (2019).

Mao, L. et al. Magnetic field sensor based on cascaded microfiber coupler with magnetic fluid. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 093102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4962177 (2016).

Bai, X. et al. Magnetic field sensor using fiber ring cavity laser based on magnetic fluid. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 28, 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2015.2487379 (2016).

Ma, Z. et al. A highly sensitive magnetic field sensor based on a tapered microfiber. IEEE Photon. J. 10, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2018.2862949 (2018).

Wang, W., Zhang, H., Li, B., Li, Z. & Miao, Y. Optical fiber magnetic field sensor based on birefringence in liquid core optical waveguide. Opt. Fiber Technol. 50, 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2019.03.011 (2019).

Liu, H., Chen, C., Wang, H. & Zhang, W. Simultaneous measurement of magnetic field and temperature based on surface plasmon resonance in twin-core photonic crystal fiber. Optik 203, 164007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.164007 (2020).

Huang, H. et al. A highly magnetic field sensitive photonic crystal fiber based on surface plasmon resonance. Sensors 20, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185193 (2020).

Fu, X. et al. A multi-directional magnetic field sensor based on tapered few mode fiber and magnetic fluid. Optik 240, 166817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.166817 (2021).

Ding, W., Jiang, Y., Gao, R., Wang, Z. & Liu, Y. An in-line photonic crystal fibre-based mach–zehnder interferometer with temperature compensation. Measur. Sci.Technol. 25, 107002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/25/10/107002 (2014).

Hu, D. J. J., Wong, R.Y.-N. & Shum, P. P. Photonic Crystal Fiber-Based Interferometric Sensors. Select. Top. Opt. Fiber Technol. Appl.https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70713 (2018). (InTech)

Shao, M., Sun, H., Liang, J., Han, L. & Feng, D. In-fiber michelson interferometer in photonic crystal fiber for humidity measurement. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 1561–1567. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2020.3019717 (2021).

Wei, T., Lan, X., Zhang, Y. & Xiao, H. Fiber inline core-cladding-mode interferometer fabricated by CO2 laser irradiation. In Xiao, H., Fan, X. & Wang, A. (eds.) Photonic microdevices/microstructures for sensing, vol. 7322, 7 – 11, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.818624. International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE, 2009).

Choi, H. Y., Kim, M. J. & Lee, B. H. All-fiber Mach–Zehnder type interferometers formed in photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Express 15, 5711–5720. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.15.005711 (2007).

Sangian, H., Mirzaee, O. & Tajally, M. Reverse chemical co-precipitation: An effective method for synthesis of BiFeO3 nanoparticles. Acerp 3, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.30501/ACP.2017.70043 (2017).

Mortensen, N. A., Nielsen, M. D., Folkenberg, J. R., Petersson, A. & Simonsen, H. R. Improved large-mode-area endlessly single-mode photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Lett. 28, 393–395. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.28.000393 (2003).

Mitu, S. A. et al. Design of magnetic fluid sensor using elliptically hole assisted photonic crystal fiber (PCF). J. Superconducti. Novel Magn. 33, 2189–2198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-020-05476-4 (2020).

Nemala, H. et al. Investigation of magnetic properties of fe3o4 nanoparticles using temperature dependent magnetic hyperthermia in ferrofluids. J. Appli. Phys. 116, 034309. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4890456 (2014).

Ghorbani, M., Hamishehkar, H., Arsalani, N. & Entezami, A. A. Preparation of thermo and pH-responsive polymer@Au/Fe3O4 core/shell nanoparticles as a carrier for delivery of anticancer agent. J. Nanopart. Res. 17, 305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-015-3097-z (2015).

Xia, J., Wang, F., Luo, H., Wang, Q. & Xiong, S. A magnetic field sensor based on a magnetic fluid-filled fp-fbg structure. Sensors 16, https://doi.org/10.3390/s16050620 (2016).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Magnetically-modulated refractive index of magnetic fluid films. Appli. Phys. Lett. 81, 4931–4933. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1531831 (2002).

Horng, H. E., Hong, C.-Y., Yang, S. Y. & Yang, H. C. Designing the refractive indices by using magnetic fluids. Appli. Phys. Lett. 82, 2434–2436. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1568147 (2003).

Chen, L. X., Huang, X. G., Zhu, J. H., Li, G. C. & Lan, S. Fiber magnetic-field sensor based on nanoparticle magnetic fluid and fresnel reflection. Opt. Lett. 36, 2761–2763. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.36.002761 (2011).

Yoshida, K., Ohkubo, K., Ojima, N. & Iwata, K. Application of the critical angle method to refractive index measurement of human skin in vivo under partial contact. J. Biomed. Opt. 18, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.18.3.037002 (2013).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Thermal effect on the field-dependent refractive index of the magnetic fluid film. Appli. Phys. Lett. 82, 3481–3483. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1576292 (2003).

Hong, C.-Y., Horng, H. E. & Yang, S. Y. Tunable refractive index of magnetic fluids and its applications. Phys. Status Solidi (c) 1, 1604–1609, https://doi.org/10.1002/pssc.200304388 (2004). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/pssc.200304388.

Wang, J. et al. Magnetic field and temperature dual-parameter sensor based on magnetic fluid materials filled photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Express 28, 1456–1471. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.377116 (2020).

Miao, Y. et al. Magnetic field tunability of optical microfiber taper integrated with ferrofluid. Opt. Express 21, 29914–29920. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.21.029914 (2013).

Li, E. Temperature compensation of multimode-interference-based fiber devices. Opt. Lett. 32, 2064–2066. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.32.002064 (2007).

Lei, X. Q., Peng, B. J., Chen, D. R., Shi, Q. G. & Ma, X. W. An all-fiber magnetic field sensor based on dual-s-shaped optic fiber integrated with magnetic fluid. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2015.2496402 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Novel magnetic field sensor based on magnetic fluids infiltrated dual-core photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Fiber Technol. 20, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2013.12.008 (2014).

Gangwar, R. K., Bhardwaj, V. & Singh, V. K. Magnetic field sensor based on selectively magnetic fluid infiltrated dual-core photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Eng. 55, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.OE.55.2.026111 (2016).

Ding, X. Z. et al. Mach–zehnder interferometric magnetic field sensor based on a photonic crystal fiber and magnetic fluid. Appl. Opt. 57, 2050–2056. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.57.002050 (2018).

Wang, H., Pu, S., Wang, N., Dong, S. & Huang, J. Magnetic field sensing based on singlemode–multimode–singlemode fiber structures using magnetic fluids as cladding. Opt. Lett. 38, 3765–3768. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.38.003765 (2013).

Gao, R. & Jiang, Y. Magnetic fluid-filled microhole in the collapsed region of a photonic crystal fiber for the measurement of a magnetic field. Opt. Lett. 38, 3181–3184. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.38.003181 (2013).

Chen, Y., Han, Q., Liu, T., Yan, W. & Yao, Y. Magnetic field sensor based on ferrofluid and photonic crystal fiber with offset fusion splicing. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 28, 2043–2046. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2016.2555320 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Temperature-compensated magnetic field sensor based on surface plasmon resonance and directional resonance coupling in a d-shaped photonic crystal fiber. Optik 158, 1402–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.01.033 (2018).

qin Lei, X., chao Xu, Y., ting Yu, Y. & jin Peng, B. Fiber in-line magnetic field sensor based on Mach–Zehnder interferometer integrated with magnetic fluid. Optoelectron. Lett. 15, 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11801-019-8087-4 (2019).

Sharma, A. K. & Popescu, V. Magnetic field sensor with truncated honeycomb photonic crystal fiber: analysis under the variations in magnetic fluid composition and temperature for high performance in near infrared. Opti. Quantum Electron. 53, 145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-021-02795-1 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. provided the idea and designed the experiments, F.B. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.Gh. helped perform the experimental analysis with constructive discussions. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taghizadeh, M., Bozorgzadeh, F. & Ghorbani, M. Designing magnetic field sensor based on tapered photonic crystal fibre assisted by a ferrofluid. Sci Rep 11, 14325 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93568-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93568-z

This article is cited by

-

Clad-modified fiber-optic magnetic field sensing characteristics of anion-doped bismuth manganite nanopowders

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.