Abstract

Marital disruption is a common life event with potential health implications. We examined the prospective association of divorce/widowhood with subsequent lifestyles, psychological, and overall health outcomes within short and longer terms using three waves of data from the 45 and Up Study in Australia (T1, 2006–09; T2, 2010; T3, 2012–16). Marital status and health-related outcomes were self-reported using validated questionnaires. Nine outcomes were examined including lifestyles (smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity), psychological outcomes (distress, anxiety and depression) and overall health/quality of life. Logistic regression was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and baseline health outcomes. Of the 33,184 participants who were married at T1 (mean age 59.5 ± 9.3 years), after 3.4 years, 2.9% became divorced and 2.4% widowed at T2. Recent divorce was positively associated with smoking, poor quality of life, high psychological distress, anxiety and depression at T2. Similar but weaker associations were observed for widowhood. However, these associations were much attenuated at T3 (5 years from T2). Marital disruption in midlife or at an older age can be detrimental to health, particularly psychological health in the short term. Public awareness of the health consequences of spousal loss should be raised. Resources, including professional support, should be allocated to help individuals navigate these difficult life transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marital status and transitions may have important implications for health. It is generally well recognised that marriage can be protective for health and reduce morbidity and mortality1. Possible explanations for the beneficial effects of marriage may include a sense of greater social and financial support, overall healthier behavioural patterns, and self-selection where healthier individuals tend to marry2. In contrast, transitions out of marriage, such as becoming divorced or widowed, are stressful life events that have been associated with poor health and survival outcomes1,3,4. Marital disruption is a common life event: around 42% of marriages in England and Wales5 and about a third of marriages in Australia end in divorce 6. Between 1990 and 2010, the divorce rate in American adults aged 50 years and above doubled, implying a rising trend of “grey divorce”7. Even if a marriage survives without divorce, it will inevitably end with the death of a spouse, leaving the other one in widowhood, often for years. Several meta-analyses have shown that compared to married adults, divorced and widowed adults have a higher risk of mortality from all causes1,8,9 and specific causes including cardiovascular disease (CVD)4 and cancer10.

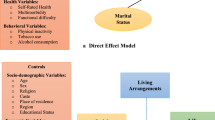

Contrary to the consistent observations about the disadvantage in health and survival following divorce or widowhood, the mechanisms underpinning these associations are less understood11. Amato’s Divorce-Stress-Adjustment Perspective postulates that the process of divorce leads to stressors, which in turn, increases emotional, behavioural and health risk. The risk, which could be either short- or long-term, may differ by individual characteristics and circumstances12. Within this model, psychological distress is a significant intermediate outcome of marital dissolution/bereavement, which may arise from financial and emotional challenges, and can lead to adverse health outcomes11. Another plausible intermediate outcome includes changes in lifestyle behaviours, which may be developed as a coping mechanism to deal with psychological distress, or a response to environmental, financial and other circumstantial changes. Such psychological and behavioural outcomes could in turn affect health, quality of life and wellbeing in the immediate-to-long term and longevity in the long term. To date, there has been limited longitudinal research on how divorce/widowhood affects both psychological wellbeing13 and lifestyle behaviours14,15,16. Furthermore, individuals respond and adjust to marital disruption differently12. Specifically men and women may have different coping strategies to psychological stressors17, and suffer from different consequences as a result of marital disruption18. For example, recent marital disruption has been associated with increased alcohol intake19 and decreased body mass index and vegetable intake in men14, and higher physical activity levels and a higher risk of smoking initiation/relapse in women15. Individuals with better socioeconomic status20 and social resources, such as supportive friends21, have also been reported to better cope with marital disruption.

With most marriages ending in divorce or widowhood, understanding the implications of marital disruption on health has important relevance to the life of many around the world. To date, most research has focused on the more “distal” outcomes, such as mortality. It is important to investigate modifiable and immediate outcomes on the pathways that lead to ill-health so that health deterioration may be prevented. It is also informative to examine whether such potential health effects persist over time. Such knowledge could improve the current understanding of the effects of major life events on health and inform interventions that aim to help individuals during marriage disruption. Moreover, previous research more commonly focused on divorce in younger populations, while the body of literature on divorce in older populations is much smaller despite the large proportion and the rising trend in “grey divorce”7. The objectives of this study were to examine the association of divorce and widowhood with subsequent changes in groups of selected outcomes: (1) health-related lifestyles, (2) psychological health, and (3) overall health and wellbeing, within both immediate and longer terms in middle-aged and older Australian adults.

Methods

Study population

Study participants were a subsample from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study. Between February 2006 and December 2009, 267,153 adults aged 45 years and above from the state of New South Wales, Australia, submitted the baseline survey (T1, participation rate: 18%)22. Prospective participants were randomly sampled from the Services Australia (formerly the Australian Government Department of Human Services) Medicare enrolment database, which provides near complete coverage of the population. People aged 80 and over and residents of rural and remote areas were oversampled. In 2010, the first 100,000 respondents were invited to participate in a sub-sample follow-up study (T2): the Social, Economic, and Environmental Factor study (SEEF) (participation rate: 64.4%)23. Between 2012 and 2016, all living baseline participants were invited to participate in a full-sample follow-up, and 142,500 (53%) returned the survey (T3). Participants completed consent forms for all surveys. The baseline and full-sample follow-up data collection was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: HREC 05035) and the SEEF study by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 10-2009/12187). The reporting of our analysis follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (Supplementary file).

The study sample for the main analysis (Analysis 1) that focused on immediate outcomes included 33,184 men and women who reported to be in a married or cohabiting relationship at T1 and completed the marital status question at T2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). For those with additional follow-up data at T3, we conducted a subgroup analysis on the longer-term effects of marital disruption (Analysis 2) among those who reported to be married at T1, reported marital status at T2 and T3, and did not change marital status between T2 and T3 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Measures

Sex-specific baseline and full-sample follow-up questionnaires can be found at https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/questionnaires/. The SEEF questionnaire is included in Supplementary File.

Exposure variable

For the purpose of the study, both divorce/separation and widowhood were considered marital disruption14,24, but were considered as separate categories in the analysis because the two events usually happen at different stages in life within distinct circumstances and may have different implications on health14. For the purpose of the analysis, we combined those who were married and in a de facto relationship (living with a partner) together as “married”, because in Australia, those in a de facto relationship are considered legally similar to married couples25. In our sample, those in a de facto relationship are slightly younger than their legally married counterparts and account for 7% of the participants who were classified as “married” at T1. For Analysis 1, those who were married at both T1 and T2 were defined as “remained married”, those who were married at T1 but reported to be single, divorced or separated at T2 were defined as “recently divorced/seperated (‘divorced’ thereafter)” and those who were married at T1 but widowed at T2 were defined as “recently widowed”. For Analysis 2, those who reported to be in a married relationship at all three time points were defined as “continuously married”, and those who reported to be single, divorced or separated at T2 and T3 were defined as “remained divorced” and those who reported to be widowed at T2 and T3 were defined as “remained widowed”. Because the objective of Analysis 2 is to examine long-term implications of divorce and widowhood, we focused the analysis on those whose marital status remained the same between T2 and T3, and excluded those who became divorced or widowed between T2 and T3 due to the recency of events (n = 1768), those who remarried/re-partnered between T2 and T3 due to the lack of consistent exposure (n = 145), and those who changed between divorced and widowed because the events were difficult to interpret (n = 27).

Outcome measures

We examined nine self-reported outcome variables in three categories: (1) health-related lifestyles: smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity; (2) psychological outcomes: psychological distress, anxiety and depression; (3) overall health and wellbeing: self-rated health and quality of life. Responses were coded as 1 for being “at risk” and 0 for “not at risk”, as described in Table 1.

Covariates and effect modifiers

The following variables were selected as covariates: age (continuous), sex, educational attainment (up to 10 years, high school/diploma/trade, university), residential location (major city vs regional/remote, based on the Accessibility Remoteness Index of Australia26), country of birth (Australia vs overseas) and follow-up time. Specifically, we selected education, rather than income, as a socioeconomic indicator, because previous research repeatedly concluded that education generally has the strongest effects on health behaviors27, and it has nearly complete data in the 45 and Up Study. Therefore, it has been consistently recommended as a stable and reliable socioeconomic indicator for the current cohort28,29.

In addition, several variables were selected as potential effect modifiers based on evidence from previous studies, including: age categories, sex, educational attainment and social support14,17,21,30,31,32. Based on previous evidence suggesting that friends’, rather than family’s support buffers health deterioration following marriage disruption21, we used one question from the Duke Social Support Index33 to measure social support outside of family. The question asks about the number of people outside of home within one hour of travel one can depend on or feel close to. Based on previous investigation in the SEEF study, this single question had the most consistent association with psychological distress across sex and age categories and was therefore chosen as an indicator for social support34. Responses were dichotomised at the median into low (0–4 people) and high (5 + people).

Statistical analysis

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics and health-related outcomes of the three marital transition groups were compared using ANOVA and χ2 tests. For Analysis 1, those who remained married served as the reference category when comparing outcomes with those who became divorced and widowed. For Analysis 2, those who were “continuously married” between T1 and T3 served as the reference category when comparing outcomes with those who “remained divorced” or “remained widowed”. Separate binary logistic regression models were fitted for each dichotomous outcome, adjusted for all covariates and the value of each outcome at T1. Effect modification was tested by including a multiplicative interaction term in the adjusted model followed by a likelihood ratio test. Given the small amount of missing data (< 8%), we used missingness as a category for analysis. Considering that people who became divorced or widowed by T2 may be at a higher risk for death or loss to follow up by T3, posing threats to selection bias, we conducted additional analyses outlined in Supplementary file (page 5 “Methodological supplement”). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and significance levels were set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

Approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: HREC 05035) and the SEEF study by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 10-2009/12187).

Results

Baseline descriptive statistics

Of the 33,184 participants who were married at baseline (T1, 2006–2009), after a mean follow-up time of 3.35 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.95) years, 31,760 (95.7%) remained married at the first follow-up (T2, 2010), 616 (2.9%) became divorced and 808 (2.4%) became widowed. At T1, compared with those who remained married, those who recently divorced were younger and had slightly higher levels of education, were less likely to live in major cities and more likely to be born overseas. On the contrary, those who recently widowed were much older, predominantly females, had lower educational attainment, and were less likely to live in major cities (Table 2).

At T1, compared with those who remained married, those who recently divorced had around twice the prevalence of fair/poor self-rated health and quality of life, high psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and reported smoking. They also had a slightly higher prevalence of high alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and insufficient fruit and vegetable intake. Those who were recently widowed had a higher prevalence of fair/poor self-rated health and quality of life, high psychological distress, and physical inactivity, but lower prevalence of depression, smoking, at-risk alcohol consumption, and insufficient fruit and vegetable intake.

Analysis 1: short-term health outcomes following marital disruption

After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, health-related outcomes at T1, and follow-up time, those who recently divorced had much higher odds of fair/poor quality of life (Odds Ratio [OR] = 2.98), high psychological distress (OR = 2.78), smoking (OR = 2.40), anxiety (OR = 2.23) and depression (OR = 2.92) at T2 (Table 3). The associations of divorce with fair/poor self-rated health (OR = 1.22), high alcohol consumption (OR = 1.12), physical inactivity (OR = 1.04) and insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption (OR = 1.25) were non-significant. For nearly all outcomes, adjusting for covariates attenuated the associations. When comparing those who were recently widowed with those who remained married, based on adjusted analysis, recent widows had higher odds of fair/poor quality of life (OR = 1.80), high psychological distress (OR = 1.92), anxiety (OR = 1.55), depression (OR = 2.11), smoking (OR = 2.51), and insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption (OR = 1.60). Recent widows also had a marginally lower prevalence of high alcohol consumption at T2 (OR = 0.75).

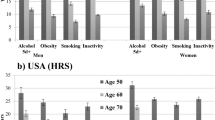

Several sociodemographic characteristics seemed to have moderated the association between marital disruption and short-term health outcomes (Table 4). Specifically, the association between divorce and quality of life was the strongest (OR = 4.91) in the oldest group (75 + years), but the association between widowhood and quality of life was the strongest (OR = 3.35) in the youngest group (45–59 years). On the other hand, the associations of both divorce and widowhood with psychological distress were the strongest in the youngest group (OR = 2.98 and 3.53, respectively). The association between divorce and high psychological distress was stronger among those with lower education attainment (OR = 2.96, up to 10 years education; OR = 3.06, high school/diploma) but the association between widowhood and psychological distress was stronger among those with high educational attainment (OR = 4.20). The association of divorce with depression was much stronger in men (OR = 4.59) than women (OR = 1.60) but the association of widowhood was similar by sex. While there was no significant association between divorce and alcohol consumption, recent widowhood seemed to reduce the risk of high alcohol consumption among women (OR = 0.53). Finally, while there was no observed association between divorce and physical activity, widowhood was significantly associated with insufficient physical activity in those with a medium level of educational attainment only (OR = 1.46).

Analysis 2: long-term health outcomes following marital disruption

After an additional five years (mean = 4.98, SD = 0.53) of follow-up, a total of 21,605 participants reported marital status at the second follow-up (T3, 2012–2016) and did not change relationship status between T2 and T3, so that consistent relationship patterns could be determined and long-term outcomes of marital disruption that occurred between T2 and T3 could be examined. Of this subgroup of participants, 20,900 were consistently married (96.7%), 270 (1.25%) remained divorced and 435 (2.01%) remained widowed. The comparison of baseline characteristics across the three groups remained similar to that from Analysis 1 (Supplementary Table 1). When adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, health-related outcomes at T1, and follow-up time, those who remained divorced still had higher odds for most adverse health outcomes compared with those who were consistently married (Table 5), but the associations were much weaker compared with those observed in Analysis 1, and only reached statistical significance for insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption (OR = 1.55). Compared with those who were consistently married, those who remained widowed did not have consistently higher odds for adverse health outcomes and none of the associations was statistically significant. We did not find significant effect modification by age, sex, educational attainment, or social support.

Discussion

This study examined the short- and long-term health outcomes following divorce and widowhood in a large population-based Australian sample of older men and women. The findings revealed strong and adverse short-term effects of marital disruption on health outcomes, particularly within the psychological health domain. These effects seemed to attenuate in the longer term.

A number of studies have examined the associations between marital status or marriage disruption and health, with relatively consistent findings suggesting a protective effect of marriage, and respectively detrimental effects of marital disruption. For example, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently found an elevated risk of all-cause mortality in adults who are divorced35 or widowed1,8,9, and the effects seemed to be mostly consistent across countries and geographic areas1,9. Wong et al. extended the outcomes for CVD and found similar associations between marital status and CVD events and mortality4. Our current study has extended previous research by examining a broad range of relatively proximal outcomes, and in a population-based sample ranging from middle age to the “oldest old”. Examining proximal outcomes could help understand the potential mechanisms (e.g., psychological distress, unhealthy lifestyles) for the observed association between marital disruption and distal endpoints, such as mortality. Understanding the potential mechanisms has been considered an important research agenda for future studies35. Involving a large sample with a broad age range allows us to examine the effect of marital disruption at different life stages, including the less researched transitions, such as divorce at an old age (grey divorce)7 and widowhood at a younger age.

To date, several proposed mechanisms might explain the health disparities by marital status4. The predominant debate has centered around social selection versus causation36. While selection theory suggests that people with poorer health are less likely to enter or maintain long-term partnerships4,36, social causation theory postulates that marriage and partnership benefit individuals’ health through spousal support, companionship and financial stability36,37,38. Within the causation theory framework, it has been proposed that the stress related to spousal loss could affect physical, mental, emotional and behavioural health4,36,38,39,40. In the current study we tested various components of these theories by: (1) comparing baseline characteristics of participants with different marriage transitions, (2) adjusting for potential confounders that could have caused self-selection into maintained partnership, such as socioeconomic status, and (3) comparing between those who have divorced and widowed, which involve different levels of self-selection.

Based on the baseline comparison of participants with different marital transition categories, those who became divorced at T2 appeared to be distinctly different from the other categories at T1: they had around twice the prevalence of fair/poor self-rated health and quality of life, high psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and current smoking, compared with those who remained married between T1 and T2. In most cases, they had much worse health risk profiles than those who became widowed, despite the latter being significantly older. Such observations may provide supportive evidence for the social selection theory. However, given that the deterioration of marriage is a gradual process, which started from the time when couples still lived together12, a dysfunctional relationship could have adversely affected physical and mental health years before divorce or separation formally took place12. In both short- and longer-term analyses, adjusted associations were much attenuated from the unadjusted associations, suggesting that the potential characteristics underlying social selection to marriages, such as socioeconomic status, may have partially contributed to the observed “marital disruption effects”. However, the adjusted associations remained strong in most cases, implying the plausibility for a causal relationship. Finally, we found generally similar patterns of associations for divorce and widowhood; if social selection was the sole explanation for the detrimental health effects of marital disruption, then one should expect strong effects of divorce but much weaker-to-no effects of widowhood, because spousal death is usually beyond the control of the surviving spouse24.

As an attempt to explore different mechanistic pathways, assuming that marital disruption is causally linked to health deterioration, we tested several domains of health outcomes: health-related lifestyle behaviours, psychological outcomes, and overall health and wellbeing. Our findings suggest that most of the observed “marital disruption effects” occurred within the psychological domain, with divorce and widowhood triggering initial elevations in psychological distress, anxiety and depression. The much higher odds of smoking among those who recently divorced or widowed, similar to findings from a previous study15, could also be stress-related41. Contrary to previous studies14,15,42, we found no overall associations between marital disruption and physical activity or alcohol consumption. We did, however, find a positive association between divorce/widowhood and insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption. Based on a small number of studies, vegetable consumption seemed to decline in men14 and women15 following divorce and widowhood, and the literature has cited a lack of food preparation skills among men14 and meal skipping as a grief reaction among women15. Finally, within the overall health and wellbeing domain, recently divorced and widowed individuals suffered from worsening quality of life but not self-rated health. This could be because the self-rated health question focuses on the physical manifestation of health while the quality of life question holistically captures physical, mental, emotional and other aspects of health, which are more likely to be influenced by marital disruption.

An interesting finding is that although marital disruption seemed to have a detrimental effect on various health outcomes in the short-term, after a further five years of follow-up, the effects were attenuated, and in some cases, disappeared. These findings confirmed the “divorce-stress-adjustment perspective”12, which postulates that marital disruption led to multiple stressors (e.g., loss of custody of children, economic decline), which, in turn, lead to negative emotional, behavioural and health outcomes. The process of “adjustment” takes time, and its severity and duration differ by individual characteristics12. Previous research found a similar “time effect” (where the negative consequences of marital disruption was attenuated over time) with depression43, first-time myocardial infarction44 but mixed results with mortality40,45. However, it is important to distinguish our study from those with morbidity or mortality endpoints, which take longer to manifest. Given that outcomes in our study are conceptually proximal, and that most people have the psychological resilience to eventually recover from marriage disruption46, we could expect on average a stronger effect in the short-term than the long-term.

However, it is important to acknowledge individual differences in resilience to stressful transitions like divorce and widowhood46. We have tested for several potential effect modifiers and found several outcome-specific interactions. For example, overall, younger participants (aged 45–59 years at T1) seemed to have suffered more from both divorce and widowhood in terms of worsening quality of life and increasing psychological distress. This finding is concordant with previous research on marital transition and mortality9. In terms of psychological distress, participants with high educational attainment seemed to have coped with divorce the best but widowhood the worst. This is a new and unexpected finding and may be related to the higher levels of independence, resources and support among those with higher socioeconomic status to cope with an expected traumatic event, such as divorce. Widowhood is less planned and more permanent and may exert severe emotional stress on individuals in the short-term, regardless of skills, resources and support. Divorce had a much stronger impact on depression in men than women, which is consistent with the literature on divorce and mortality8,9. It has been documented that men are more likely to dramatically lose supportive social ties9 and experience declined social support from their children following a divorce47. Finally, interestingly, women who were widowed seemed to have benefited from reduced heavy alcohol consumption. A previous study in France found that women decreased heavy drinking prior to and at the time of widowhood48. Some evidence suggests that husbands may influence wives’ drinking behaviour49, it is plausible that the death of a husband may be associated with reduced drinking occasions.

Limitations

The current study is the first to our knowledge to examine short- and longer-term effects of marital disruption on a broad range of physical, psychological and behavioural health outcomes in middle-aged and older adults. Strengths include a population-based sample, comprehensive proximal health outcomes, and examination of both divorce and widowhood. However, findings should be interpreted in light of limitations. First, some relevant information was not collected by the 45 and Up Study, such as relationship quality, the exact time of marital transition (we could only infer that the event happened between T1 and T2), the long-term cumulative marital history (e.g., the total number of marriages and broken relationships)35. Such information is important to further elucidate whether the adverse health effects of marital disruption are due to social selection or causation. While this study focused on marital disruption, the other type of marital transition, namely remarriage could further affect health behaviours and outcomes. However, we did not model this transition because of the small number of participants who remarried and the lack of repeated measures to ascertain long-term effects of remarriage. Second, there was some evidence for selection bias as those who became divorced or widowed by T2 were more likely to become lost to follow-up by T3 (Supplementary file). Third, the number of participants who became divorced or widowed during the study follow-up was small, limiting the power of detecting potential associations and effect modification. Fourth, the 45 and Up Study cohort was not population representative and participants were on average healthier than the general population. However, a study comparing the current cohort with a population representative sample in New South Wales found the estimates for the associations between risk factors and health outcomes to be similar, despite the differences in risk factor prevalence50. Finally, it is important to note that the current study was conducted based on a sample aged 45 years and above and we only examined the effects of marital disruption in midlife and at an older age. Findings may not generalise to younger populations.

Conclusions

This current Australian study extends previous evidence on marital transition and health and suggests that marital disruption can be a vulnerable life stage, particularly for certain subgroups, such as men. Findings from the study have important public health implications. Given the ubiquitous and inevitable nature of marital disruption, it is important to raise public awareness of its potential health effects and develop strategies to help individuals navigate such difficult life transitions. Physicians and other health practitioners who have access to regularly updated patient information may play an important role in identifying at-risk individuals, monitoring their health and referring them to potential interventions and support programs.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Sax Institute upon application and payment, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Sax Institute.

References

Manzoli, L., Villari, P., Pirone, G. M. & Boccia, A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 64, 77–94 (2007).

Kim, H. K. & McKenry, P. C. The relationship between marriage and psychological well-being: A longitudinal analysis. J. Fam. Issues 23, 885–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251302237296 (2002).

Manfredini, R. et al. Marital status, cardiovascular diseases, and cardiovascular risk factors: A review of the evidence. J. Womens Health 26, 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6103 (2017).

Wong, C. W. et al. Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 1, 1937–1948 (2018).

Office for National Statistics. What Percentage of Marriages End in Divorce? (Office for National Statistics, 2013).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Social Trends, 2007 (No. 4102.0). Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/26D94B4C9A4769E6CA25732C00207644?opendocument (2007).

Brown, S. L. & Lin, I. F. The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 67, 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs089 (2012).

Moon, J. R., Kondo, N., Glymour, M. M. & Subramanian, S. V. Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 6, e23465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023465 (2011).

Shor, E., Roelfs, D. J., Bugyi, P. & Schwartz, J. E. Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: Reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.010 (2012).

Pinquart, M. & Duberstein, P. R. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 75, 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003 (2010).

Sbarra, D. A., Hasselmo, K. & Nojopranoto, W. Divorce and death: A case study for health psychology. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 6, 905–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12002 (2012).

Amato, P. R. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J. Marriage Fam. 62, 1269–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x (2000).

Gähler, M. “To divorce is to die a bit...”: A longitudinal study of marital disruption and psychological distress among Swedish women and men. Fam. J. 14, 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480706290145 (2006).

Eng, P. M., Kawachi, I., Fitzmaurice, G. & Rimm, E. B. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviours in US male health professionals. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 59, 56–62 (2005).

Lee, S. et al. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviours in US women. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34, 69–78 (2005).

Stahl, S. T. & Schulz, R. The effect of widowhood on husbands’ and wives’ physical activity: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Behav. Med. 37, 806–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9532-7 (2014).

Das, A. Spousal loss and health in late life: Moving beyond emotional trauma. J. Aging Health 25, 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312464498 (2013).

Leopold, T. Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: A study of multiple outcomes. Demography 55, 769–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0667-6 (2018).

Pudrovska, T. & Carr, D. Psychological adjustment to divorce and widowhood in mid- and later life: Do coping strategies and personality protect against psychological distress?. Adv. Life Course Res. 13, 283–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(08)00011-7 (2008).

Kulik, L. & Heine-Cohen, E. Coping resources, perceived stress and adjustment to divorce among Israeli women: Assessing effects. J. Soc. Psychol. 151, 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903366453 (2011).

Bookwala, J., Marshall, K. I. & Manning, S. W. Who needs a friend? Marital status transitions and physical health outcomes in later life. Health Psychol. 33, 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000049 (2014).

Banks, E. et al. Cohort profile: The 45 and up study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37, 941–947. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym184 (2008).

Bauman, A. et al. Maximising follow-up participation rates in a large scale 45 and up study in Australia. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 13, 6–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-016-0046-y (2016).

Cornelis, M. C. et al. Bachelors, divorcees, and widowers: Does marriage protect men from type 2 diabetes?. PLoS ONE 9, e106720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106720 (2014).

Australian Government. Guides to Social Policy Law: Social Security Guide. 2.2.5.10 Determining a De Facto Relationship, https://guides.dss.gov.au/guide-social-security-law/2/2/5/10 (2019).

Department of Health and Aged Care. Measuring Remoteness. Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2001).

Pampel, F. C., Krueger, P. M. & Denney, J. T. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36, 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529 (2010).

Stamatakis, E. et al. Associations between socio-economic position and sedentary behaviour in a large population sample of Australian middle and older-aged adults: The Social, Economic, and Environmental Factor (SEEF) Study. Prev. Med. 63, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.009 (2014).

Korda, R. J. et al. Socioeconomic variation in incidence of primary and secondary major cardiovascular disease events: An Australian population-based prospective cohort study. Int. J. Equity Health 15, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0471-0 (2016).

Dupre Matthew, E., George Linda, K., Liu, G. & Peterson Eric, D. Association between divorce and risks for acute myocardial infarction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 8, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001291 (2015).

Floud, S. et al. Marital status and ischemic heart disease incidence and mortality in women: A large prospective study. BMC Med. 12, 42–42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-42 (2014).

Hughes, R., Good, E. S. & Candell, K. A longitudinal study of the effects of social support on the psychological adjustment of divorced mothers. J. Divorce Remarriage 19, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v19n01_03 (1993).

Goodger, B., Byles, J., Higganbotham, N. & Mishra, G. Assessment of a short scale to measure social support among older people. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 23, 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01253.x (1999).

Phongsavan, P. et al. Age, gender, social contacts, and psychological distress: Findings from the 45 and up study. J. Aging Health 25, 921–943. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264313497510 (2013).

Sbarra, D. A., Law, R. W. & Portley, R. M. Divorce and death: A meta-analysis and research agenda for clinical, social, and health psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611414724 (2011).

Wade, T. J. & Pevalin, D. J. Marital transitions and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 45, 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650404500203 (2004).

Espinosa, J. & Evans, W. N. Heightened mortality after the death of a spouse: Marriage protection or marriage selection?. J. Health Econ. 27, 1326–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.001 (2008).

Matthews, K. A. & Gump, B. B. Chronic work stress and marital dissolution increase risk of posttrial mortality in men from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.3.309 (2002).

Quinones, P. A. et al. Marital status shows a strong protective effect on long-term mortality among first acute myocardial infarction-survivors with diagnosed hyperlipidemia—Findings from the MONICA/KORA myocardial infarction registry. BMC Public Health 14, 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-98 (2014).

Brenn, T. & Ytterstad, E. Increased risk of death immediately after losing a spouse: Cause-specific mortality following widowhood in Norway. Prev. Med. 89, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.019 (2016).

Kassel, J. D., Stroud, L. R. & Paronis, C. A. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol. Bull. 129, 270–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270 (2003).

Liew, H. The effects of marital status transitions on alcohol use trajectories. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 3, 332–345 (2012).

Kristiansen, C. B., Kjaer, J. N., Hjorth, P., Andersen, K. & Prina, A. M. The association of time since spousal loss and depression in widowhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54, 781–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01680-3 (2019).

Kriegbaum, M., Christensen, U., Andersen, P. K., Osler, M. & Lund, R. Does the association between broken partnership and first time myocardial infarction vary with time after break-up?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1811–1819. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt190 (2013).

Berntsen, K. N. & Kravdal, O. The relationship between mortality and time since divorce, widowhood or remarriage in Norway. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 2267–2274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.028 (2012).

Sbarra, D. A., Hasselmo, K. & Bourassa, K. J. Divorce and health: Beyond individual differences. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414559125 (2015).

Kalmijn, M. Gender differences in the effects of divorce, widowhood and remarriage on intergenerational support: Does marriage protect fathers?. Soc. Forces 85, 1079–1104. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0043 (2007).

Tamers, S. L. et al. The impact of stressful life events on excessive alcohol consumption in the French population: Findings from the GAZEL cohort study. PLoS ONE 9, e87653. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087653 (2014).

Leonard, K. E. & Das Eiden, R. Husband’s and wife’s drinking: Unilateral or bilateral influences among newlyweds in a general population sample. J. Stud. Alcohol. Suppl. 13, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.130 (1999).

Mealing, N. et al. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 10, 26 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW; and partners: the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division); NSW Ministry of Health; NSW Government Family & Community Services—Ageing, Careers and the Disability Council NSW; and the Australian Red Cross Blood Service. We thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.D. conceptualised the research idea, D.D. and J.G. conducted data analysis, B.N. and D.D. conducted the literature review, D.D. drafted the manuscript with B.N. contributing to parts of the manuscript, all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, D., Gale, J., Bauman, A. et al. Effects of divorce and widowhood on subsequent health behaviours and outcomes in a sample of middle-aged and older Australian adults. Sci Rep 11, 15237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93210-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93210-y

This article is cited by

-

Marital dissolution and associated factors in Hosanna, Southwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study

BMC Psychology (2023)

-

Union Status and Disability Pension

European Journal of Population (2023)

-

Network and solitude satisfaction as modifiers of disadvantages in the quality of life of older persons who are challenged by exclusion from social relations: a gender stratified analysis

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.