Abstract

In the situation of high maternal morbidity and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa, less than 80% of pregnant women receive antenatal care services. To date, the overall effect of antenatal care (ANC) follow up on essential newborn practice have not been estimated in East Africa. Therefore, this study aims to identify the effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice in East Africa. We reported this review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). We searched articles using PubMed, Cochrane library, African journal online (AJOL), and HINARI electronic databases as well as Google/Google scholar search engines. Heterogeneity and publication bias between studies were assessed using I2 test statistics and Egger’s significance test. Forest plots were used to present the findings. In this review, 27 studies containing 34,440 study participants were included. The pooled estimate of essential newborn care practice was 38% (95% CI 30.10–45.89) in the study area. Women who had one or more antenatal care follow up were about 3.71 times more likely practiced essential newborn care compared to women who had no ANC follow up [OR 3.71, 95% CI 2.35, 5.88]. Similarly, women who had four or more ANC follow up were 2.11 times more likely practiced essential newborn care compared to women who had less than four ANC follow up (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.33, 3.35). Our study showed that the practice of ENBC was low in East Africa. Accordingly, those women who had more antenatal follow up were more likely practiced Essential newborn care. Thus, to improve the practice of essential newborn care more emphasis should be given on increasing antenatal care follow up of pregnant women in East Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) essential newborn care utilization is a strategic approach to improve the health of newborns through interventions rendered prior to conception, during pregnancy, during delivery and soon after birth and during the postnatal period1.

Globally, neonatal death accounts for about 44% of under-five mortality and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest rates of neonatal mortality accounting 38% of all neonatal deaths2.

In developing countries, neonatal mortality has remained resistant to change3,4. About three-fourths of deaths among new-born occur in the first week of life, and 25–40% occurs in the first 24 h5,6.

Most causes of neonatal death are preventable and related to cord care to decrease sepsis, temperature control by delaying first bath and initiation of early breastfeeding which has the additional benefit of controlling hypothermia7,8,9,10.

Essential Newborn Care (ENBC) utilization is one of the recommended strategies by World Health Organization (WHO) to reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity in both community and facility delivery11. ENBC practices include clean cord care, thermal care and initiating breast feeding immediately or within the first hour after birth3,6,12,13.

The Ethiopian government has paid special attention to the expansion of quality high impact neonatal interventions by establishing basic newborn care units in health centers and in hospital’s neonatal intensive care units14,15.

Most newborn deaths occur at home in low- income countries including east African regions due to a lack of access to health care, a limited number of trained health care personnel, and an overall weak health system in the regions16.

Hence for safe home based deliveries new strategies should be developed. Thus, essential newborn care practice should be designed for neonates who cannot be managed at home in ensuring proper referral. Further, in domestic settings it would help as an appropriate means of the newborns care17.

In developing countries there is low level of adherence to essential new-born care practice despite this recommendation. Accordingly, reports from east African countries demonstrated the low level of essential new-born care practice16,18,19,20,21. For example in Uganda early bathing and spread over materials on cord stump is a custom21,22,23. Similarly, studies done in different parts of Ethiopia also demonstrated the low level of utilization of essential new-born care6,24,25,26,27,28.

In east Africa region the period after delivery is frequently noticeable by traditional practices. Bathing the baby immediately following delivery, applying diverse matters on the umbilical cord and giving various pre-lacteal feeds for the neonates were most important cultural performs hamper the health and survival of the newborn. Even if understanding these cultural practices is an essential part of confirming effective and timely newborn care; there is inadequate documented evidence in east Africa where sub-optimal newborn care practices has been widely described 3,29,30.

Antenatal period (ANC) is one of the instruments to obtain reduction in neonatal mortality by counseling pregnant women to have access for essential newborn care practices preparing them to care for their newborn when they visit health facilities and during home visits made by community health workers3,31.

Various studies have assessed factors affecting essential newborn care utilization in East Africa6,24,25,26,27,28. But none of them identified the pooled effect of ANC on essential new born care use in East Africa. Therefore, this meta-analysis summarizes the effect of ANC on essential newborn care practice among women in East Africa systematically and quantitatively. Thus, the findings will help to determine how much of an impact have antenatal care follow up on essential newborn care practice in East Africa. In addition, this study provides comprehensive information for policy makers and program managers to design strategies that increase the utilization of essential newborn care.

Methods

Searching strategies

This systematic review has been prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline32. The systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number: CRD42020207894).

We searched articles using PubMed, Cochrane library, African journal online (AJOL), and HINARI electronic databases as well as Google/Google scholar search engines.

A medical subject head (MeSH) and keyword items was used in separate and combination using Boolean operator: “OR”, “AND” or “NOT” in order to identify relevant articles. Thus, searches was conducted using Keywords/search terms like “Prevalence”, “proportion”, “magnitude”, “essential”, “essential newborn care” “newborn”, “neonatal care”, “newborn care”, “utilization”, “services”, “practices”, “Antenatal care”, “prenatal care”, “maternal health care”, “delivery care”, “East Africa”.

Inclusion criteria’s

Study design and period: all observational studies conducted in East Africa published until September, 2020 were included in this review and meta- analysis.

Participants: women who delivered either in the health facility or at the home.

Setting: All community-based and facility-based studies reported ENBC utilization and ANC follow up.

Language: Articles published in English language.

Exposure: ANC follow up.

Outcome: Essential newborn care (ENBC) utilization/practice.

We excluded Primary studies inaccessible for full-text article after 2 times author request. In addition, those articles published in non-English languages were also excluded from this review and meta-analysis.

Data extraction and synthesis

A standardized data extraction format was prepared in the form of Microsoft Excel.

The data extraction format includes author, year of publication, study country, year of publication, study period, study setting, study design, sample size, number of subjects with outcome, ANC follow up, and essential newborn care practice.

Three reviewers (ETA, MY, BK) independently extracted the data and any disagreements between the reviewers were solved through consensus. For incomplete data, we excluded the study after attempts to contact the corresponding author through email.

The quality of the studies was assessed using Joana Briggs Institute (JBI) adapted for observational studies by 2 Authors (MA, WM) before analysis and any discrepancy was resolved by discussion and consensus33,34.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

We identified the heterogeneity between the studies using I2 statistics and P values35. A forest plot was used to detect the presence of heterogeneity. Furthermore, subgroup analysis and meta-regression was used to identify the possible source of heterogeneity.

To check publication bias, both objective and subjective (funnel plot) methods were used. The presence of publication bias was checked using subjective method (funnel plot) symmetry. In addition, the statistical significance of publication bias was assessed using objective method s Egger’s and Beggar’s test (P < 0.05)36,37.

Statistical analysis

After extracting the data, we imported into STATA Version 14.0 statistical software for further analysis. The analysis to identify the effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care service use was categorized into two parts. The first analysis was to identify the effect of one or more ANC visits on essential newborn care service use and the second was an analysis of the effect of four or more ANC visits on essential newborn care service use. A random effects meta-analysis model was employed to estimate the DerSimonian and Laird’s pooled effect because of high levels of heterogeneity38. The results were presented in tables and forest plot.

Results

Study selection and screening

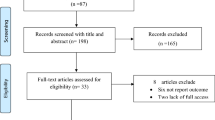

As described in Fig. 1 a total of 741 records were retrieved through database searching. Of this 20 articles were removed due to duplication and about 681 articles were removed after reviewing their title and abstracts. About 40 articles were selected for full text review. From these, 5 studies were excluded for not reporting the outcome variable, 5 studies by the study design, and 3 studies by quality of the study. Finally, 27 articles met the eligibility criteria included in the final Meta-analysis (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Description of studies

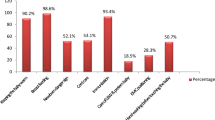

In this review, a total of 34,440 study participants from 27 studies were included. The studies were conducted from 2007 to 2019 and published from 2010 to 2020. Regarding study country, most of the studies (17) were conducted in Ethiopia. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 192 to 22,243. In terms of study design, majority of the studies (26) were cross-sectional. From a total of 27 articles included in this review, about 17 of them were community-based and the remaining 10 were institutional-based studies (Table 1).

The quality of the studies was assessed using Joana Briggs Institute (JBI) adapted for observational studies by independent evaluators before analysis. We included those studies that fitted to 50% and above the quality assessment checklist. Hence, the results of quality assessment ranged from 60 to 80% and all studies were fit for analysis (Table 1).

Meta-analysis

In this review and meta-analysis about 27 studies were included to estimate the pooled estimate of essential newborn care practice among women in East Africa. The level of essential newborn care practice was ranged 1.17–92.91% from the included studies (Fig. 2). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the overall pooled estimate of essential newborn care practice was 38% (95% CI 30.10–45.89). In this study, I2 statistic was detected considerable and significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 99.7, P value < 0.0001). Therefore, a random effect model was used to estimate the overall pooled prevalence of essential newborn care practice in East Africa.

We conducted meta-regression using different factors to identify the possible source of heterogeneity between studies. But, there was no statistical significance variation from the meta-regression result. In addition, subgroup analysis was conducted to explore the source of heterogeneity in Essential newborn care practice using different factors included in the study. But, no significant change was seen as compared with the main meta-analysis. Hence, the heterogeneity might be explained by other covariates which are not included in this study.

Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was done to identify influential studies. According to the analysis, all of the studies were included in the final analysis since no influential studies were detected.

Publication bias

We have checked publication bias of the included studies using Funnel plot and egger tests. Accordingly, Egger’s test showed no statistically significant publication bias (P = 0.64). As depicted in Fig. 3 the funnel plot has also indicated the absence of publication bias since studies represented by dots were asymmetrical (Fig. 3).

Effect of antenatal care follow up on essential newborn care practice

We included a total of 6 cross- sectional studies to estimate the effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice in east Africa. The participants of the studies ranged from 417 to 834 (Table 2). The included studies showed significant heterogeneity and detected using I2 statistic (I2 = 74.0%, P value = 0.002) (Fig. 4). Therefore, a random effect model was used to estimate the overall pooled effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care in the study area.

As described in Fig. 4 the random effect model analysis showed, women who had one or more antenatal care follow up were 3.71 times more likely practiced essential newborn care compared to mothers who had no ANC visit [OR 3.71, 95% CI 2.35, 5.88] (Fig. 4).

In order to identify the effect of four or more ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice about 4 additional studies with 2140 participants were included. The studies were conducted from 2012 to 2018 and published from 2015 to 2019 (Table 3).

Significant heterogeneity was observed between studies and detected using I2 statistic (I2 = 68.1, P = 0.024) (Fig. 5). Thus, a random effect model was used to estimate the pooled effect of four and more ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice in the study area (Table 3).

The pooled effect of 4 studies revealed having four or more ANC follow up was significantly associated with essential newborn care practice in East Africa. Figure 5 illustrated women who had four or more ANC follow up were 2.11 times more likely practiced essential newborn care compared to women who had less than four ANC follow up (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.33, 3.35).

Discussion

Antenatal care has been used as a strategy to reduce maternal and newborn morbidities and mortalities. In developing countries, different strategies have been implemented to improve the effectiveness of Antenatal care. Nowadays, most developing regions including East African regions used the focused ANC approach which was developed by WHO39,40.

Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to estimate the pooled prevalence of newborn care practice and identify the effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice among post-partum women in East Africa.

This review study estimated that the level of Essential newborn care practice among postpartum women in East Africa was 38%. This finding was lower as compared to a meta-analysis done in Ethiopia about 48.77%7, Nepal about 70.7%41, and India about 66.70%42. The possible justification for the discrepancy may be due to differences in socio-economic, differences in socio-cultural aspects, differences in study setting, and differences in sample size. In addition, the discrepancy may be due to the variation in maternal health services coverage across countries based on increased awareness and information about ENBC utilization.

This study revealed that women who attended antenatal care were more likely practiced essential newborn care in the study regions.

Concordant to this result there was a report from low income country43 and Northern Ghana44. This could be related that mothers who visited Antenatal care follow up had an opportunity of obtaining health workers information about the importance of newborn care practice through attending health facilities. Further, Antenatal care has a positive association with essential newborn practices including clean cord care and thermal care44. Furthermore, during immediate ANC visits they told from health professional about essential newborn care practice that helps to provide appropriate and timely periodic advice consult which would in turn increases the utilization newborn care45.

This review and meta-analysis had using large sample size, which meant that it could detect the effect of ANC on essential new born care practice. However, the study does not address other factors that influence essential newborn care practice.

This research is important for understanding the effect of ANC follow up on essential newborn care practice in East Africa. The finding is also relevant for policymakers to establish criteria for improving the quality of maternal and newborn care in East Africa.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that Essential newborn care practice among women in East Africa was low. Women who had one or more antenatal care follow up were more likely practiced essential newborn care in East Africa. Thus, women who attend four or more Antenatal care visits were more practiced essential newborn as compared to those who have less than four follow ups in the study area. Therefore, the governments and concerned bodies should give special attention to increase Antenatal care follow up of women to improve essential newborn care use.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- ENBC:

-

Essential newborn care

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Narayanan, I., Rose, M., Cordero, D., Faillace, S., & Sanghvi, T. The components of essential newborn care; 2004.

Mohammadi, Y. et al. Levels and trends of child and adult mortality rates in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1990–2013; protocol of the NASBOD study. Arch. Iran. Med. 17(3), 176–181 (2014).

Tafere, T. E., Afework, M. F. & Yalew, A. W. Does antenatal care service quality influence essential newborn care (ENC) practices? In Bahir Dar City Administration, North West Ethiopia: A prospective follow-up study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 44, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0544-3 (2018).

Knippenberg, R. et al. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet 365(9464), 1087–1098 (2005).

United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (IGME). Levels and Trends in Child Mortality (UNICEF, 2017).

Efa, B. W. et al. Essential new-born care practices and associated factors among post-natal mothers in Nekemte City, Western Ethiopia. PLoS One 15(4), e0231354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231354 (2020).

Alamneh, Y. et al. Essential newborn care utilization and associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2804-7 (2020).

Gary, L. D. et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: How many newborn babies can we save?. Lancet 365, 977–988 (2005).

Save the Children. Ending Newborn Deaths: Ensuring Every Baby Survives (Save the Children, 2014).

de Graft Johnson, J. et al. Cross-sectional observational assessment of quality of newborn care immediately after birth in health facilities across six sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Open 7, e014680. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014680 (2017).

Workinesh, D., Tsion, A., Mulugeta, S. & Behailu, T. Knowledge and practice of essential newborn care among postnatal mothers in Addis Ababa City Health Centers, Ethiopia. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 11(8), 170–179 (2019).

Marsh, D. R. et al. Advancing newborn health and survival in developing countries: A conceptual framework. J. Perinatol. 22(7), 572–576 (2002).

WHO, United Nations Population Fund, UNICEF. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice, 3rd edn. ISBN: 978 92 4 154935 6 (2015).

Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Management Protocol manual. (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014).

National Newborn and Child Survival Strategy Document Brief Summary. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health 2015-19. 1-13 (2015).

Rosales, A. C. et al. Essential newborn care in rural settings: The case of Warrap State in SouthSudan. Afr. Eval. J. 2(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.4102/aej.v2i1.80 (2014).

Munn, Z., Moola, S., Riitano, D. & Lisy, K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 3(3), 123 (2014).

Amolo, L., Irimu, G. & Njai, D. Knowledge of postnatal mothers on essential newborn care practices at the Kenyatta National Hospital: A cross sectional study. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 28, 97. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.97.13785 (2017).

MOH Burundi. Annual Statistic Data of Health Centers and Hospitals in 2014 (Direction of National Health Information Management System, MOH Burundi, 2015) (French).

Makene, C. L. et al. Improvements in newborn care and newborn resuscitation following a quality improvement program at scale: Results from a before and after study in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-014-0381-3 (2014).

Monebenimp, F. et al. Mothers ‘knowledge and practice on essential newborn care at health facilities in Garoua City, Cameroon. Health Sci. Dis. 14, 2 (2013).

Waiswa, P., Peterson, S., Tomson, G. & Pariyo, G. W. Poor newborn care practices—a population-based survey in Eastern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10(1), 1 (2010).

Saaka, M. & Iddrisu, M. Patterns and determinants of essential newborn care practices in rural areas of Northern Ghana. Hindawi Publ. Corp. Int. J. Popul. Res. 2014, 10 (2014).

Kokebie, T., Aychiluhm, M. & Alamneh, G. D. Community based essential new-born care practices and associated factors among women in the rural community of Awabel District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2013. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 1, 17–27 (2015).

Callaghan-Koru, J. A. et al. New born care practices at home and in health facilities in 4 regions of Ethiopia. BMC Paediatr. 13(1), 1 (2013).

Amsalu, R. et al. Essential newborn care practice at four primary health facilities in conflict affected areas of Bossaso, Somalia: A cross-sectional study. Confl. Health 13, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0202-4 (2019).

Weldeargeawi, G. G., Negash, Z., Kahsay, A. B., Gebremariam, Y. & Tekola, K. B. Community-based essential newborn care practices and associated factors among women of Enderta, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2020(ArticleID 2590705), 7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2590705 (2020).

Mersha, A. et al. Essential newborn care practice and its predictors among mother who delivered within the past six months in Chencha District, Southern Ethiopia, 2017. PLoS One 13(12), e0208984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208984 (2018).

Duysburgh, E. et al. Quality of antenatal and childbirth care in selected rural health facilities in Burkina Faso, Ghana and Tanzania: Similar finding. Trop. Med. Int. Health 18, 534–547 (2013).

Ayiasi, M., Kasasa, S., Criel, B., Orach, G. & Kolsteren, P. Is antenatal care preparing mothers to care for their newborns? A community-based cross-sectional study among lactating women in Masindi, Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(1), 114 (2014).

Bergsjo, P. What is the evidence for the role of antenatal care strategies in the reduction of maternal mortality and morbidity? In Studies in Health Services Organization & Policy, Vol 17 (eds Van Lerberghe, W. et al.) 35–54 (Safe Motherhood Strategies, 2011).

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Control Found. Appl. 4(1), 1 (2015).

Munn, Z., Moola, S., Lisy, K., Riitano, D. & Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13(3), 147–153 (2015).

Moola, S. et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327(7414), 557 (2003).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4), 1088–1101 (1994).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109), 629–634 (1997).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp. Clin. Trials 45, 139–145 (2015).

Tunçalp, Ӧ et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience going beyond survival. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 124(6), 860–862 (2017).

WHO. Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. ISBN: 9789241549912 (2016).

Tuladhar S. The determinants of good newborn care practices in the rural areas of Nepal (University of Canterbury, 2010).

Castalino, F., Nayak, B. S. & D’Souza, A. Knowledge and practices of postnatal mothers on newborn care in tertiary care hospital of Udupi District. Nitte Univ. J. Health Sci. 4(2), 98 (2014).

Tegene, T., Andargie, G., Nega, A. & Yimam, K. Newborn care practice and associated factors among mothers who gave birth within one year in Mandura District, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin. Mother Child Health 12, 1 (2015).

Saaka, M. & Iddrisu, M. Patterns and determinants of essential newborn care practices in rural areas of northern Ghana. Int. J. Popul. Res. 4(1), 1–10 (2014).

Baqui, A. H. et al. Newborn care in rural Uttar Pradesh. Indian J. Pediatr. 74(3), 241–247 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors of the primary studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.T.A.: conception of research protocol, study design, literature review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation and drafting the manuscript. B.K., A.M., Z.F., R.D., Y.D., B.A., W.M.A., M.G., M.Y., M.S., G.B., T.C.M., M.A., and M.A.: data analysis, reviewing the manuscript, data extraction and quality assessment. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amsalu, E.T., Kefale, B., Muche, A. et al. The effects of ANC follow up on essential newborn care practices in east Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11, 12210 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91821-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91821-z

This article is cited by

-

Disparity of Neonatal Care Visits by Region in Indonesia: A Secondary Data from Basic Health Research

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.