Abstract

Resistance plasmids play a crucial role in the transfer of antimicrobial resistance from the veterinary sector to human healthcare. In this study plasmids from foodborne Escherichia coli isolates with a known (ES)BL or tetracycline resistance were sequenced entirely with short- and long-read technologies to obtain insight into their composition and to identify driving factors for spreading. Resistant foodborne E. coli isolates often contained several plasmids coding for resistance to various antimicrobials. Most plasmids were large and contained multiple resistance genes in addition to the selected resistance gene. The majority of plasmids belonged to the IncI, IncF and IncX incompatibility groups. Conserved and variable regions could be distinguished in each of the plasmid groups. Clusters containing resistance genes were located in the variable regions. Tetracycline and (extended spectrum) beta-lactamase resistance genes were each situated in separate clusters, but sulphonamide, macrolide and aminoglycoside formed one cluster and lincosamide and aminoglycoside another. In most plasmids, addiction systems were found to maintain presence in the cell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistance plasmids are instrumental in spreading resistance within and between veterinary and human healthcare1,2,3,4. The spread of resistance genes happens fast between cells of similar, but also different species of bacteria5,6. With increasing frequency Escherichia coli infections become untreatable due to extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) or beta-lactamases (BL) encoded on resistance plasmids and the WHO assigned highest priority to research on this subject7. In livestock (ES)BL and tetracycline resistance, which are mostly plasmid mediated, cause the greatest risks8. Tetracycline resistance was present in 77% of E. coli strains isolated from a swine feeding facility9 and chicken meat isolates in Germany showed high prevalences of (ES)BLs with the highest resistance percentage found for cefotaxime (74%)10. This antibiotic resistance can transfer from cattle directly to farmers11,12 as well as from foodstuffs to human healthcare13. Sources such as uncooked meat can spread antibiotic resistance14. To better understand the spreading of resistance mediated by plasmids, we need to understand the composition and maintenance systems of these plasmids.

Plasmids are classified usually by incompatibility group15. Incompatibility is assumed to be caused by competition for replication systems16. The idea is that two plasmids that compete for the same replication system cannot co-exist within a cell line over multiple generations. This characteristic is used to classify plasmids accordingly. The most common incompatibility group associated with (ES)BL resistance is IncF17. (ES)BL resistance has also been found in other incompatibility groups that are considered endemic resistance plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae such as IncI.

Plasmids contain a conserved region and a variable region18. The conserved region harbors the incompatibility group/replication genes, the genes for transfer and sometimes those for maintenance of the plasmid19,20. These genes are found to be similar per incompatibility group. The variable region contains mostly accessory genes such as resistance genes and can differ from plasmid to plasmid18. Transfer systems and mechanisms have been extensively described as well as some maintenance systems such as genes involved in partitioning21,22,23,24,25. Resistance genes have been researched in depth on function26. The composition of a single plasmid isolated from Aeromonas hydrophila was examined by comparative sequence analysis grouping the genes mainly based on function27. Comparison of this plasmid with sequences of similar plasmids in databases resulted in patterns found in similar plasmids from different species, including E. coli, and from different hosts such as human, bovine, beef, chicken and fish. The same prevalence of comparable plasmids was found using similar approaches across different species and a wide variety of locations28,29.

Analysis of the overall composition of resistance plasmids may provide insights into the spreading dynamics and what type of resistance plasmids can be transferred from livestock to human health care. Most studies have focused on certain elements within these plasmids, such as the transfer system22,30, resistance genes11,17,31,32,33,34, addiction system25,35,36, etc. While this proves useful information in their respective fields, the analysis of all information encoded on plasmids can discern patterns that explicate how plasmids function and behave. This can in turn explain the spread of antibiotic resistance mediated by these plasmids.

This research focusses on the composition and architecture of plasmids from veterinary E. coli species, given their role in spreading resistance to human health care. Two main questions are addressed: is it possible to distinguish specific regions or gene clusters in these plasmids that are linked to resistance, transfer, or maintenance? Are resistance gene regions or clusters conserved or variable within a plasmid and can this explain the mobility of the resistance genes? To answer these questions, plasmids present in E. coli isolated from chicken, turkey and beef that coded for (ES)BL or tetracycline resistance were sequenced using both long and short read technology. The results were hybrid assembled and analyzed for their composition and architecture. The entire plasmids per strain were mapped and analyzed for patterns. These patterns are used to explain epidemiological observations.

Results

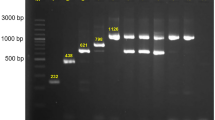

Gel electrophoresis of plasmids isolated from different E. coli strains from meat destined for the consumer market shows that most strains contained several plasmids of different sizes (Fig. 1). Figure 1 should only be regarded as an illustration since the sizes are not determined well due to supercoiling and because the larger plasmids were underrepresented in these particular samples. Out of 17 strains analyzed 14 contained more than one plasmid (Table 1). Ample quantities of isolated plasmids were analyzed by next generation de novo-sequencing in order to obtain sufficient genetic material also of the largest plasmids, up to 190 kb.

None of the strains contained two plasmids belonging to the same incompatibility group (Table1). The most common incompatibility groups in this set of strains are part of the IncI-family, IncX-family and IncF-family 34 out of 42 plasmids. IncI was found far more in poultry isolates (eight out of nine plasmids) than in beef isolates (one out of nine plasmids). All other plasmid types were distributed equally over the different kinds of meat. Other plasmids found were IncB/O/K/Z, IncR, IncN and P0111 as well as some plasmids containing mainly phage like genes (phage/phage plasmid) (8 out of 42 plasmids). Out of 16 plasmids containing IncF-group replicons, ten contained two or three replicons within a single plasmid. While this is not common for other incompatibility groups, multiple replicons found in a plasmid is common in the IncF-family37. The size of plasmids corresponded to the replicon-type for IncI and IncX, at between 90 and 120 kb and 30–60 kb, respectively. The plasmids containing IncF replicons differed in size: from around 40 kb up to more than 190 kb. Measurements of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) using six antimicrobials of five different classes revealed that all strains were resistant to more than one antibiotic (data not shown). The MIC showed in some cases discrepancies with the AMR genes found. This was in most cases due to a resistance that is most likely genomic, since it showed up in the MIC but not as AMR gene on the plasmid. The most striking difference was found for strain ESBL3284, were it was expected to find beta-lactam gene CMY-2 on a plasmid (as screened before by WBVR) and showed a slightly higher MIC for ampicillin and amoxicillin than sensitive strains. The plasmid however did not harbour the CMY-2 gene and hence this is most likely a genomic resistance. Sequencing of the genome has not been performed, but transfer experiment data suggest that since no successful transfers were found, this gene might be genomic. Out of 42 plasmids recovered, 31 contained between 1 and 10 resistance genes (Table 1). Most plasmids coded for multiple resistant genes (18 out of 42), some did not contain resistance genes (13 out of 42) and 13 contained only a single resistance gene. The most common belonged to the (ES)BL-group (bla), others were part of the tetracycline group (tet), aminoglycoside group (aad, aac, ant & aph), sulphonamides (sul), trimethoprim (dfr), chloramphenicol (cat, cml & flo), fluoroquinolone (qnr), macrolides (mac), lincosamides (lnu) and colistin (mcr). The macAB and floR genes were never accompanied by another resistance gene on the same plasmid. Most plasmids contained a toxin-antitoxin system, also referred to as an addiction system25. Only 8 out of the 42 plasmids examined here did not contain such a system. The phd-doc system was mostly found in IncI replicon types, while hicAB or relE-relB/stbD were mostly associated with IncX replicon types. IncF-type plasmids contained a wide variety in addiction systems and often multiple systems were discovered in a single plasmid. In all, 16 plasmids contained only one addiction system, while the maximum number of addiction systems found was five.

The structures of the plasmids were analyzed for common elements and recurring gene clusters. The clusters described were selected on the basis of common elements in resistance genes. In Fig. 2 clusters are shown that were found in plasmids coding for beta-lactam, tetracycline, macrolide, sulphonamide and aminoglycoside resistance. Specific clusters encoding for beta-lactam resistance genes were identified including blaCMY-2, blaCTX-M-1 and genes from the blaTEM family. The resistance gene clusters were accompanied by mobile genetic elements, such as transposases and insertion sequences. Some of the clusters contained an additional small multi-drug resistance gene. The tetracycline resistance cluster contained tetA and tetR next to a permease of the drug/metabolite transporter superfamily, a transposase from the Tn3-family and a relaxase (Fig. 2A). The macrolide/sulphonamide/aminoglycoside resistance cluster contained the mobile genetic element IS26, macrolide resistance gene mefB, sulphonamide resistance gene sul3 (dihydropteroate synthase), a transposase, small multidrug resistance gene qacE, and 2 aminoglycoside resistance genes from the aadA family (Fig. 2B). Lincosamide/aminoglycoside cluster was associated with mobile genetic element IL-IS_2, integrase intI1 and transposase Tn21 (Fig. 2C). The cluster around beta-lactamase blaCMY-2 included mobile genetic element ISEc9, lipocalin blc, small multidrug resistance gene sugE (Fig. 2D). The cluster containing blaCTX-M-1 existed in two different modes: while always associated with a tryptophan synthase, it was either found next to insertion sequence ISEc9 (Fig. 2E1) or next to a replication protein and insertion sequence IS26 (Fig. 2E2). The plasmids described also contained other types of blaCTX-M genes, but these where not located in the same cluster. Beta-lactamases of the blaTEM-family were often found in a cluster next to transposase Tn3 and a recombinase (Fig. 2F). While the cluster around blaCMY-2 was always linked with the IncI replicon, the other clusters were distributed among different plasmid types. Additional clusters associated with resistance against heavy metals were also identified but are not described here.

Shows six different resistance gene clusters found over different plasmids. Showing cluster (A) including genes coding for tetracycline resistance, cluster (B) with genes encoding for macrolide, sulphonamide and aminoglycoside resistance, and small multidrug resistance sugE, cluster (C) containing genes encoding for lincosamide and aminoglycoside resistance, cluster (D) containing specific beta-lactamase resistance gene blaCMY-2, cluster (E) containing specific beta-lactamase resistance gene CTX-M-1 in 2 versions and cluster (F) including specific beta-lactamase resistance gene from the TEM family. (G) contains a table showing the number of times a cluster was found in the dataset and the corresponding E. coli strain and Inc plasmid type.

Table 2 shows the specific subtypes found for the three most commonly found incompatibility groups in this data set: IncF, IncI and IncX. The IncF plasmids show the highest number of subtypes and only two of the subtypes are found twice. Some of the subtypes also include novel alleles not found in the database. The IncI plasmids show more similarities in subtypes, where subtype 3 and 12 are found multiple times. The IncX plasmids in this study can be split into two groups, since only the X1 and X4 subtypes were detected.

Figure 3 shows the homology of the four most commonly found plasmid/replicon types. The IncI containing plasmids showed the most overlap and least and smallest gaps (Fig. 3A). Subtype 3 as found in ESBL2057, 2073 and 3153 shows an even higher overlap, but in general the subtypes are all quite similar. The IncB/O/K/Z plasmids were also compared with the IncI plasmids, since they showed a high homology in architecture. IncF containing plasmids have the least amount of overlap. They can be grouped together in three sets of plasmids showing higher homology among each other. The subtypes do not seem to be linked to these three groups as well as the size of the plasmids. The IncX subtypes IncX1 and IncX4 were split into two groups which have high homology within, but not between each other. Both showed a high amount of conservation within their subtypes with few gaps. The clusters shown in Fig. 2 are located in these gaps. These gaps further contain accessory genes like, heavy metal or other types of resistances and addiction systems.

In Fig. 4, a single consensus sequence is presented for IncI, IncX1 and IncX4. Hypothetical proteins of unknown function have been omitted. An IncF consensus sequence could not be reconstructed, because of lower homology and higher variation between these plasmids. Regions can be identified in all consensus sequences that correspond to clusters of genes involved in plasmid transfer and clusters involved in plasmid maintenance. The IncI replicon containing plasmids all harbor plasmid transfer genes from the tra-family, where the IncX plasmids contain type IV secretion system genes (virB) for transfer. Plasmid maintenance genes that are preserved for the IncI plasmids contain the addiction system phd-doc, SOS inhibition genes (psiAB), some plasmid partition and stability genes, a surface exclusion gene and a post-segregation killing gene (unidentified addiction system). The IncX1 plasmids contained more plasmid maintenance genes than the IncX4 harboring plasmids, such as partition genes parA and parG, the kikA gene as well as the addiction system relE-relB/stbD. Interestingly, the IncX1 also included a preserved resistance gene for chloramphenicol, where the other two types of plasmids do not. The IncX4 plasmids had only one addiction system (hicAB) and the kikA gene as homologous genes involved in plasmid maintenance. Both IncX4 and IncX1 plasmids also had the replication gene conserved (PI protein) in contrast to IncI plasmids which contained multiple subtypes of the different IncI-family replication genes. Some mobile elements were also preserved within the consensus sequences. The two separate IncX consensus sequences had a few of the same genes in common, especially belonging the type IV secretion system.

Three examples of plasmid architecture based on consensus domains are presented in Fig. 5. The replicons and sequences of IncI immediately downstream from the origin were considerably different from each other, causing an area with little alignment, defined as less than 70% homology (Fig. 5A). The remainder of the plasmids showed increasing homology as demonstrated by the colors and the decreasing number of gaps. Five clusters can be identified. A first cluster appears after between 9 and 17 kb and includes the doc toxin and 3′,5′-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Starting around 20–30 kb we find a cluster including a resolvase, putative plasmid partition protein, plasmid stability proteins, lesion bypass DNA polymerase umuCD and adenine specific methyltransferases. The third cluster spans from around 30 to 76 kb containing ykfF, psiAB, eea, ardA, ydfB, mobile element proteins, relaxosome component, relaxase, conjugal transfer proteins, post-segregation killing protein, phage minor tail protein, surface exclusion protein, transfer proteins traW, traU, traS, traR, traJ, traI, traH, traG and a shufflon-specific DNA recombinase. From 76 to 88 kb, a fourth cluster is described containing only pilus or conjugative transfer proteins known as pilV, pilT, pilS, pilR, pilQ, pilP, pilN, pilM, pill, pilK and pilI. The last cluster contains three more transfer proteins, traA, traB and traC and spans over the section from 88 to 91 kb.

Alignment of IncI plasmids (A), IncX1 plasmids (B) and IncX4 plasmids (C) showing the alignment of all similar plasmids among all E. coli strains tested in this dataset against the annotated consensus sequence. Colors indicate the homology, where full color show 100% identity, slightly lighter color indicates 90% identity or higher, grey indicates 70% identity or higher and no color indicates less than 70% homology.

IncX1 has higher homology and shows no separated clusters, but instead consists of one complete plasmid (Fig. 5B). The plasmid starts with a DNA distortion protein, followed by partition protein parA, parG and again parA, then a section containing mobile elements proteins including resolvase, transposase and relaxases, followed by a chloramphenicol resistance gene (floR), transcriptional regulator lysR, haemolysin expression modulating protein, transfer gene of the traE-type, kikA, and a cascade of type IV secretion system genes, virD4, virB11, virB10, virB9, traG, virB5, virB3, virB4, virB2, virB1 and traR. The last bit includes another DNA distortion protein, addiction system relE-relB/stbD and ends with the replication protein (PI protein).

The IncX4 alignment can be split into two parts: one of high homology that contains all known genes and one with lower homology where no known genes could be annotated in the tail of the plasmid (Fig. 5C). The highly homologous part starts with the replication protein (PI protein), followed by mobile element proteins, dnaJ, addiction system hicAB, transfer genes belonging to the type IV secretion system including traR, traG, virB1, virB3/4, virB5, virB6, virB10 and virB11. Furthermore, it also contains the kikA protein, a putative nuclease, a traR-type gene, haemolysin expression modulating protein and a DNA-binding protein.

Discussion

Most research on resistance plasmids has focused either on comparisons of resistance genes, or on one type of plasmid, or on mobile genetic elements38, as opposed to overall plasmid composition in multiple strains. In this study, we attempt to find common elements and unifying principles in sets of plasmids found in E. coli resistant to antimicrobials. While in no way repudiating the value of other approaches, we feel that this point of view focusing on architecture and shared components adds novel insights to the understanding of plasmids.

Two separate types of regions can be distinguished in plasmids; conserved and variable regions18. The conserved regions mostly contain genes involved in replication, stability and mobility, while the variable regions contain accessory genes. In the plasmids described in this study, the consensus sequence, defined as the conserved regions per incompatibility group, is composed of genes for plasmid transfer and maintenance. The variable regions that contain the resistance genes are located in the gaps seen in the consensus sequence or in mobile genetic element sites (Figs. 2, 4 and 5). This implies that the plasmid can preserve its integrity by inserting new genes solely into designated regions and between essential genes.

Within these E. coli strains the IncI plasmids were more conserved compared to IncF-like plasmids. A variation in conserved regions within the IncF group was earlier also observed by Fernandez-Lopez et al.19, separating the IncF group into five different classes. These classes, however, did not always correspond to the range found in this study. The consensus of IncI, IncX1 and IncX4 outlines the minimum requirement for a plasmid to be classified as this type of plasmid according to this dataset. This set of similar genes suggests that crucial genes for classification are those that are involved in plasmid maintenance and plasmid transfer18,39. Possibly these represent the minimum number of genes necessary for transfer and maintenance for the corresponding plasmid type.

This study supports the theory of incompatibility16, as no two plasmids belonging to the same incompatibility group were located in the same strain. Incompatibility is caused by the competition between two plasmids using the same replication and partitioning system40,41. Hence, in theory, plasmids of two similar but not identical incompatibility groups could co-exist within one strain, if these plasmids also harbor other genes enhancing their survival such as partitioning genes or addiction systems. The less similar their incompatibility region is, the more likely plasmids are to be able to coexist within one cell42. In contrast, it is common to find multiple replicons of the same incompatibility group within one plasmid, especially for IncF and IncI type plasmids43.

Strains to be included in the study were selected for either (ES)BL or tetracycline resistance, not for multiple resistance, though further characterization often showed this. Resistance genes were frequently assembled in clusters flanked by MGEs suggesting that multiple types of resistance can be easily transferred from plasmid to plasmid or from plasmid to chromosome38. Since clusters of this kind are highly mobile, they stimulate the spread of antimicrobial resistance44. The presence of these clusters sometimes multiple times within a single strain is in line with the concept of mobile genetic elements being able to move around separately from the plasmid38,45.

Two types of multiple resistance clusters have been identified: (1) Sulphonamide, macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance and (2) lincosamide and aminoglycoside resistance (Fig. 2). The (extended spectrum) beta-lactamases and tetracycline resistance genes are more often located each in a separate cluster, suggesting that these MGEs only transfer one type of resistance. In a dataset comprising 2522 bacterial genomes antimicrobial resistance clusters were positioned close to heavy metal or chemical resistance genes46. This observation supports the idea that these categories of genes only insert within specific places within a plasmid rather than randomly47. Tetracycline clusters flanked by Tn10 are wide-spread in gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria48,49.

Beta-lactam resistance “clusters” are associated mostly with the same IS elements or transposases but not necessarily always with the same “accessory genes”31,45,48,49,50,51,52. The various clusters of CTX-M genes are highly prevalent in plasmids32,53. This in turn suggests that this class of genes might be transferred more often from cell to cell or from plasmid to plasmid than other resistance genes. Indeed, other studies have shown that ESBL plasmids can be transferred at a higher rate than tetracycline resistance plasmids54,55. The presence of TEM clusters in multiple plasmids within one cell suggests that the transposition of these genes had already taken place. The blaCMY-2 cluster is associated in this dataset only to IncI-like plasmids, as opposed to other findings that the blaCMY-2 gene itself is also associated to other replicon types such as IncA/C, IncFIA-FIB, IncNT53 as well as the entire cluster being found in IncK and/or IncB/O plasmids51. When beta-lactam resistance is induced, a section of the genome of E. coli that contains a similar cluster including ampC, the chromosomal equivalent of blaCMY-2, is replicated in high numbers56.

Addiction systems that allow plasmids to maintain themselves within a cell by producing a stable toxin and unstable anti-toxin25 are widespread35,36. Addiction systems can explain why multiple large plasmids remain in the cell over generations even in the absence of selective pressure57. Almost all plasmids in this study contained a toxin-antitoxin system. Whether these addiction systems are associated with certain plasmid types is a matter of debate. Zielenkiewicz and Ceglowski25 state: “there is no uniform pattern for the placement of stability cassettes on plasmids”. Addiction systems were judged to be randomly distributed over plasmids rather than to be associated with specific types24. Later a link was found between the beta-lactamase blaCTX-M and the addiction genes ccdAB, vagCD, and pndAC58. In the present study the phd-doc system was located on the IncI plasmids and the hicAB and relE-relB/stbD systems on the IncX plasmids, also suggesting a correlation between addiction systems and incompatibility types.

In conclusion, resistance plasmids recovered from foodborne E. coli strains share common characteristics in structure and contents that correlate to their incompatibility groups. The shared features include essential genes for plasmid transfer and maintenance. Most plasmids maintain their presence in the cell with the assistance of addiction systems59. Specific resistance clusters can be positioned in any of the plasmids investigated. As a result, resistance genes move easily and rapidly between plasmids and from plasmid to chromosomes5,6.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains

Escherichia coli strains were isolated from foodstuffs by the Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA) and characterized by Wageningen Bioveterinary Research (WBVR). Dr. Kees Veldman of WBVR selected and donated 28 strains that were known to contain plasmids. Strains originated from chicken, turkey or bovine meat and were selected for having either a beta-lactam or tetracycline resistance. The resistance was established by the NVWA by sensitivity tests60 and confirmed afterwards using MIC assays61. Plasmid presence was initially confirmed by the by detection of the incompatibility group62 and later confirmed by successful plasmid transfer experiments54 and gel electrophoresis. All E. coli strains were cultivated before plasmid isolation by first plating the strains on LB-agar plates with 64 μg/ml amoxicillin or tetracycline (to prevent plasmid loss) overnight at 37 degrees Celsius. One colony was picked and grown first in 5 ml LB with antibiotics before scaling up to 400 ml LB with antibiotics. From the final volume, cell pellets were collected.

Plasmid preparation and sequencing

The plasmids were isolated using a Qiagen Plasmid Maxi Kit, checked for purity with Nanodrop and if samples had low concentration of DNA or were too contaminated with salts they were purified with ethanol precipitation. Sequencing was performed by BaseClear B.V. (Leiden, the Netherlands) using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and PacBio systems. Hybrid de novo assembly was performed using both the generated Illumina short read and PacBio long read data. In most cases several plasmids originated from a single strain and as a result the correct assembly of the plasmids turned out to be problematic and to pose severe methodological problems. Short read data only were insufficient for plasmid assembly. In the end hybrid assembly combining long and short read data has provided high quality scaffolds that are reliable and translated back into single plasmids. Hybrid assembly was performed by first improving the quality of the Illumina reads by trimming of low-quality bases using BBDuk, part of BBMap suite version 36.77 (Bushnell B., sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). High-quality reads were assembled into contigs using ABySS version 2.0.263. The long reads were mapped to the draft assembly using BLASR version 1.3.164. Based on these alignments, the contigs were linked together and placed into scaffolds. The orientation, order, and distance between the contigs were estimated using SSPACE-LongRead version 1.065. Using Illumina reads, gapped regions within scaffolds were (partially) closed using GapFiller version 1.1066. Finally, assembly errors and the nucleotide disagreements between the Illumina reads and scaffold sequences were corrected using Pilon version 1.2167. The assembly of strains that afterwards still showed too low quality were not included in this paper. Low quality refers to too many unassembled small scaffolds, too many gaps and too low coverage of reads mapping to a scaffold. Hybrid assembly can sometimes result in the artificial fusion of plasmids within one scaffold, as also seen by Margos et al.68. This artifact was mostly caused by identical regions present in two plasmids within the same cell. These were separated afterwards, based on gel photos showing multiple bands, Illumina only data showing these specific plasmids as separated and transfer experiments resulting in the transfer of single separated plasmids. Fusion plasmids or hybrid plasmids do also occur in nature and this needs to be taken into account before splitting fused plasmids69. The scaffolds thus obtained were tested for circularity to determine if one scaffold corresponds to one full plasmid. This was determined by considering whether the scaffolds contained a full sequence of a plasmid or an overlapping gene found partly at the start and partly at the end of the sequence, as checked through BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Circularity was also based on the annotation similarities between the start and end of the sequence, such as genes commonly found next to each other. Scaffolds not corresponding to a full sequence are distinguished from the other plasmids by name. Establishing circularity was also attempted using other softwares and then seems highly likely, but could not be proven beyond any doubt.

Data analysis

The scaffold sequences were screened for resistance genes and their incompatibility group using CGEs ResFinder 4.070 and PlasmidFinder 2.171. Full annotation was performed afterwards using RAST 2.072. The annotated sequences were further analyzed using Snapgene viewer 5.1.7 (from Insightful Science; available at snapgene.com). Plasmid subtyping was done using CGEs pMLST 2.071. Plasmid alignment for the specific incompatibility groups was done using CLC Genomics Workbench 7 (https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com) and BRIG 0.9573. Imperfectly assembled plasmids were included in the alignment, but are distinguished by adding scaffold to the name. CLC workbench alignments provided a general view of matching parts in the sequences and were used to create a consensus sequence for each incompatibility group. BRIG was used to visualize the annotated consensus and the matching plasmids sequences.

References

Carattoli, A. Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 298–304 (2013).

Levy, S. B. & Marshall, B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: Causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10, S122–S129 (2004).

Lopatkin, A. J. et al. Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 8, 1689 (2017).

Sommer, M. O. A., Munck, C., Toft-Kehler, R. V. & Andersson, D. I. Prediction of antibiotic resistance: Time for a new preclinical paradigm?. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 689–696 (2017).

Dionisio, F., Matic, I., Radman, M., Rodrigues, O. R. & Taddei, F. Plasmids spread very fast in heterogeneous bacterial communities. Genetics 162, 1525–1532 (2002).

Threlfall, E. J., Ward, L. R., Frost, L. S. & Willshaw, G. A. The emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in food-borne bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 62, 1–5 (2000).

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet. Infect. Dis 18, 318–327 (2018).

Verraes, C. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the food chain: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 2643–2669 (2013).

Stine, O. C. et al. Widespread distribution of tetracycline resistance genes in a confined animal feeding facility. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29, 348–352 (2007).

Kaesbohrer, A. et al. Diversity in prevalence and characteristics of ESBL/pAmpC producing E. coli in food in Germany. Vet. Microbiol. 233, 52–60 (2019).

Dierikx, C. et al. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase- and AmpC-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Dutch broilers and broiler farmers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 60–67 (2013).

Fischer, J. et al. Simultaneous occurrence of MRSA and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae on pig farms and in nasal and stool samples from farmers. Vet. Microbiol. 200, 107–113 (2017).

Mughini-Gras, L. et al. Attributable sources of community-acquired carriage of Escherichia coli containing β-lactam antibiotic resistance genes: A population-based modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e357–e369 (2019).

CDC. 2020. Antibiotic Resistance, Food, and Food Animals. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/challenges/antibiotic-resistance.html. (Accessed 29 July 2020).

Couturier, M., Bex, F., Bergquist, P. L. & Maas, W. K. Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 52, 375–395 (1988).

Thomas, C. M. Plasmid incompatibility. Mol. Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6436-5_565-2 (2014).

Brolund, A. Overview of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae from a Nordic perspective. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 4, 10.3402/iee.v4.24555. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v4.24555 (2014).

Orlek, A. et al. Plasmid classification in an era of whole-genome sequencing: Application in studies of antibiotic resistance epidemiology. Front. Microbiol. 8, 182 (2017).

Fernandez-Lopez, R., de Toro, M., Moncalian, G., Garcillan-Barcia, M. P. & de la Cruz, F. Comparative genomics of the conjugation region of f-like plasmids: five shades of F. Front. Mol. Biosci. 3, 71 (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. Replicon-based typing of inci-complex plasmids, and comparative genomics analysis of incigamma/K1 plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 10, 48 (2019).

Arutyunov, D. & Frost, L. S. F conjugation: Back to the beginning. Plasmid 70, 18–32 (2013).

Llosa, M., Gomis-Rüth, F. X., Coll, M. & de la Cruz, F. Bacterial conjugation: A two-step mechanism for DNA transport. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1–8 (2002).

Schroder, G. & Lanka, E. The mating pair formation system of conjugative plasmids-A versatile secretion machinery for transfer of proteins and DNA. Plasmid 54, 1–25 (2005).

Unterholzner, S. J., Poppenberger, B. & Rozhon, W. Toxin-antitoxin systems: Biology, identification, and application. Mob. Genet. Elements 3, e26219 (2013).

Zielenkiewicz, U. & Ceglowski, P. Mechanisms of plasmid stable maintenance with special focus on plasmid addiction systems. Acta Biochim. Pol. 48, 1003–1023 (2001).

van Hoek, A. H. et al. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes: An overview. Front. Microbiol. 2, 203 (2011).

Del Castillo, C. S. et al. Comparative sequence analysis of a multidrug-resistant plasmid from Aeromonas hydrophila. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 120–129 (2013).

Bennett, P. M. Plasmid encoded antibiotic resistance: Acquisition and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153(Suppl 1), S347–S357 (2008).

Stokes, H. W. & Gillings, M. R. Gene flow, mobile genetic elements and the recruitment of antibiotic resistance genes into Gram-negative pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 790–819 (2011).

Costa, T. R. D. et al. Structure of the bacterial sex F pilus reveals an assembly of a stoichiometric protein-phospholipid complex. Cell 166(1436–1444), e10 (2016).

Bonnet, R. Growing group of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: The CTX-M enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 1–14 (2004).

Canton, R., Gonzalez-Alba, J. M. & Galan, J. C. CTX-M enzymes: Origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 3, 110 (2012).

Falgenhauer, L. et al. Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in Germany. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 16, 282–283 (2016).

Lo, W. U. et al. Highly conjugative IncX4 plasmids carrying blaCTX-M in Escherichia coli from humans and food animals. J. Med. Microbiol. 63, 835–840 (2014).

Moritz, E. M. & Hergenrother, P. J. Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and plasmid-encoded in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 311–316 (2007).

Williams, J. J., Halvorsen, E. M., Dwyer, E. M., DiFazio, R. M. & Hergenrother, P. J. Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are prevalent and transcribed in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 322, 41–50 (2011).

Rozwandowicz, M. et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1121–1137 (2018).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, 1–61 (2018).

Shintani, M., Sanchez, Z. K. & Kimbara, K. Genomics of microbial plasmids: Classification and identification based on replication and transfer systems and host taxonomy. Front. Microbiol. 6, 242 (2015).

Austin, S. & Nordström, K. Partition-mediated incompatibility of bacterial plasmids. Cell 60, 351–354 (1990).

Ebersbach, G., Sherratt, D. J. & Gerdes, K. Partition-associated incompatibility caused by random assortment of pure plasmid clusters. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1430–1440 (2005).

Novick, R. P. Plasmid incompatibility. Microbiol. Rev. 51, 381–395 (1987).

Sykora, P. Macroevolution of plasmids: A model for plasmid speciation. J. Theor. Biol. 159, 53–65 (1992).

von Wintersdorff, C. J. et al. Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front. Microbiol. 7, 173 (2016).

Poirel, L., Decousser, J. W. & Nordmann, P. Insertion sequence ISEcp1B is involved in expression and mobilization of a bla(CTX-M) beta-lactamase gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2938–2945 (2003).

Pal, C., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Kristiansson, E. & Larsson, D. G. Co-occurrence of resistance genes to antibiotics, biocides and metals reveals novel insights into their co-selection potential. BMC Genom. 16, 964 (2015).

Sota, M. et al. Region-specific insertion of transposons in combination with selection for high plasmid transferability and stability accounts for the structural similarity of IncP-1 plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3091–3098 (2007).

Partridge, S. R. Analysis of antibiotic resistance regions in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 820–855 (2011).

Tauch, A., Götker, S., Pühler, A., Kalinowksi, J. & Thierbach, G. The 27.8-kb R-plasmid pTET3 from Corynebacterium glutamicum encodes the aminoglycoside adenyltransferase gene cassette aadA9 and the regulated tetracycline efflux system Tet 33 flanked by active copies of the widespread insertion sequence IS6100. Plasmid 48, 117–129 (2002).

Lafond, M., Couture, F., Vézina, G. & Levesque, R. C. Evolutionary perspectives on multiresistance b-lactanase transposons. J. Bacteriol. 171, 6423–6429 (1989).

Seiffert, S. N. et al. Plasmids carrying blaCMY-2/4 in Escherichia coli from poultry, poultry meat, and humans belong to a novel IncK subgroup designated IncK2. Front. Microbiol. 8, 407 (2017).

Yamamoto, T., Yamagata, S., Horii, K. & Yamagishi, S. Comparison of transcription of b-lactamase genes specified by various ampicillin transposons. J. Bacteriol. 150, 269–276 (1982).

Carattoli, A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 2227–2238 (2009).

Handel, N., Otte, S., Jonker, M., Brul, S. & ter Kuile, B. H. Factors that affect transfer of the IncI1 beta-lactam resistance plasmid pESBL-283 between E. coli strains. PLoS ONE 10, e0123039 (2015).

Schuurmans, J. M. et al. Effect of growth rate and selection pressure on rates of transfer of an antibiotic resistance plasmid between E. coli strains. Plasmid 72, 1–8 (2014).

Hoeksema, M., Jonker, M. J., Brul, S. & Ter Kuile, B. H. Effects of a previously selected antibiotic resistance on mutations acquired during development of a second resistance in Escherichia coli. BMC Genom. 20, 284 (2019).

Tsang, J. Bacterial plasmid addiction systems and their implications for antibiotic drug development. Postdoc J. 5, 3–9 (2017).

Jo, S. J. & Woo, G. J. Molecular characterization of plasmids encoding CTX-M beta-lactamases and their associated addiction systems circulating among Escherichia coli from retail chickens, chicken farms, and slaughterhouses in Korea. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 270–276 (2016).

Makarova, K. S., Wolf, Y. I. & Koonin, E. V. Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of type 2 toxin-antitoxin systems and related mobile stress response systems in prokaryotes. Biol. Direct. 4, 19 (2009).

National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. 2020. Nethmap-Maran 2020. The Netherlands.

Schuurmans, J. M., Nuri Hayali, A. S., Koenders, B. B. & ter Kuile, B. H. Variations in MIC value caused by differences in experimental protocol. J. Microbiol. Methods 79(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2009.07.017 (2009).

Garcia-Fernandez, A., Fortini, D., Veldman, K., Mevius, D. & Carattoli, A. Characterization of plasmids harbouring qnrS1, qnrB2 and qnrB19 genes in Salmonella. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63, 274–281 (2009).

Jackman, S. D. et al. ABySS 2.0: Resource-efficient assembly of large genomes using a Bloom filter. Genome Res. 27, 768–777 (2017).

Chaisson, M.J., Tesler, G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with succesive refinement (BLASR): Application and theory. BMC Bioinform. 13, 238. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-13-238 (2012).

Boetzer, M. & Pirovano, W. SSPACE-LongRead: Scaffolding bacterial draft genomes using long read sequence information. BMC Bioinform. 15, 211 (2014).

Boetzer, M. & Pirovano, W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 13, 1–9 (2012).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Margos, G. et al. Lost in plasmids: Next generation sequencing and the complex genome of the tick-borne pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi. BMC Genom. 18, 422 (2017).

Brandt, C. et al. Assessing genetic diversity and similarity of 435 KPC-carrying plasmids. Sci. Rep. 9, 11223 (2019).

Bortolaia, V. et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkaa345 (2020).

Carattoli, A. et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903 (2014).

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 9, 75 (2008).

Alikhan, N. F., Petty, N. K., Ben Zakour, N. L. & Beatson, S. A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 12, 402 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kees Veldman en Ben Wit for providing the resistant strains and Sarah Duxbury for assistance in identifying appropriate proper analysis programs and all three for stimulating discussions. The MSc students Lisa Daniels, Sidra Kashif, Selin Alpagot and Eva Kozanli performed plasmid isolations and transfer experiments as part of their degree requirements. We thank Ali Farmand Kabir Noori for programming software to circularize plasmids and assistance with data analysis using AI methodologies.

Funding

This study was funded by Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.D. and B.K. conceived the project. S.B. assisted in the design of experiments. T.D., B.K.S. and K.B. performed experiments. T.D. performed analysis of the data. T.D. and B.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darphorn, T.S., Bel, K., Koenders-van Sint Anneland, B.B. et al. Antibiotic resistance plasmid composition and architecture in Escherichia coli isolates from meat. Sci Rep 11, 2136 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81683-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81683-w

This article is cited by

-

Multidrug-resistant conjugative plasmid carrying mphA confers increased antimicrobial resistance in Shigella

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Examining the impact of zinc on horizontal gene transfer in Enterobacterales

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Higher prevalence of CTX-M-27-producing Escherichia coli belonging to ST131 clade C1 among residents of two long-term care facilities in Southern Spain

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.