Abstract

Full body impressions and resting traces of Hexapoda can be of extreme importance because they bring crucial information on behavior and locomotion of the trace makers, and help to better define trophic relationships with other organisms (predators or preys). However, these ichnofossils are much rarer than trackways, especially for winged insects. Here we describe a new full-body impression of a winged insect from the Middle Permian of Gonfaron (Var, France) whose preservation is exceptional. The elongate body with short prothorax and legs and long wings overlapping the body might suggests a plant mimicry as for some extant stick insects. These innovations are probably in relation with an increasing predation pressure by terrestrial vertebrates, whose trackways are abundant in the same layers. This discovery would possibly support the recent age estimates for the appearance of phasmatodean-like stick insects, nearly 30 million years older than the previous putative records. The new exquisite specimen is fossilized on a slab with weak ripple-marks, suggesting the action of microbial mats favoring the preservation of its delicate structures. Further prospections in sites with this type of preservation could enrich our understanding of early evolutionary history of insects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some outcrops are clearly more favourable for the preservation of trackways, resting traces and full body impressions than for the organisms themselves. The trackways of arthropods are rather frequent in the fossil record since the Devonian. But they are especially frequent in the continental outcrops of the ‘red’ Permian in Europe and North America1,2,3. Nevertheless, the trackmakers are generally difficult to determine, especially for those attributed to arthropods4. The resting traces and the full-body impressions (FBIs) are more complex than the trackways and give more information on the external morphology of the trackmakers. FBIs can be nearly as well-preserved as a body fossils5. But these are much rarer than the trackways, and among them, those attributed to the Hexapoda are even the rarest, mainly attributed to apterous Archaeognatha (Supplementary Information)5,6,7,8,9,10,11. FBIs of winged insects are extremely rare: only 10 specimens are recorded in the world, from the Carboniferous and Permian (Table 1 in Supplementary Information) and they mostly preserve the ventral side of the trackmaker only.

Here we describe an exquisite full-body impression of an elongate winged insect strongly resembling a Phasmatodea (stick insect), from the Middle Permian of the Luc Basin (Var, Provence, France). It consists in a delicate lateral impression of the entire insect. With only few occurrences from the Middle Triassic to the Cenozoic, the fossil record of the Phasmatodea is very poor compared to that of the other Polyneoptera such as the Orthoptera12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The earliest occurrences of stick insects are scarce and based on incomplete bodies or wing fossils14,17,18,19,20.

Stick insects are one of the most specialised insect orders in term of plant mimicry. New discoveries about their early origins give clue to the development of such a defence strategy, currently known from only a few fossil taxa16,21,22,23,24. Body fossils of Phasmatodea remain unknown from the Palaeozoic. The present discovery would be the oldest evidence of a potential phasmatodean-like insect, suggesting the stick insects were already present more than 30 million years than though through other records, during the Mesozoic14,17. Independently to the taxonomic attribution of this FBI that can be only tentative by nature, the general shape of its narrow and elongate body strongly resembles that of a plant twig. Thus, it would also possibly constitutes the second oldest case of plant mimicry by insects, the first one being based on a leaf mimicry by an Orthoptera Tettigonioidea from the Roadian (Middle Permian) of Dôme du Barrot (France)24.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:985D009E-7D62-4BA4-8245-55E894563F64.

Results

Systematic paleoichnology

Ichnogenus Phasmichnus gen. nov.

-

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:0D2B8221-402F-4C7D-A8EF-D28BA690C857

-

Type species. Phasmichnus radagasti sp. nov.

-

Diagnosis. Lateral impression composed of three tagmata, the median bearing three legs. Very elongated and narrow median and posterior tagmata. Presence of long traces of putative wings whose base is behind hind legs. Abdomen with traces of terminal appendages (cerci and/or ovipositor).

-

Etymology. After Phasmatidae Gray, 1835 and ichnos (Greek for trace).

-

Composition and distribution. Only Phasmichnus radagasti sp. nov. (Middle Permian, France) (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information).

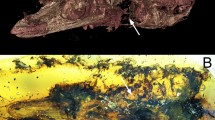

Phasmichnus radagasti sp. nov. (Figs. 1, 2)

Phasmichnus radagasti gen. et nov. sp. Interpretative drawing. Abd abdomen; a antenna; app abdominal appendages; lfw left forewing; lhw left hind wing; H head; MeTh mesothorax; MTh metathorax; mp mouthparts; PTh prothorax; rfl right foreleg; rfw right forewing; rhl right hind leg; rml right median leg; rhw right hind wing. Drawing by A.L. Scale bar, 10 mm.

-

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:3802715B-4815-4DEB-A8B4-88782A44E48F

-

Type material. Holotype MNHN.F.A71341 stored in the collection of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris.

-

Type stratum and age. Pelitic Formation, “Red Permian”, Wordian, Middle Permian.

-

Type locality. Gonfaron, Var, France.

-

Diagnosis. As for the genus.

-

Description. The trace fossil corresponds to a convex epirelief (possibly a counterpart), 43.1 mm long, 3.2 mm wide; with three distinct tagmata impressions; anterior tagma (H), 2.9 mm long and oval with a fine impressions ‘a’, curved forward, on top of ‘H’; thicker at its attachment points and tapering distally; at the bottom front of ‘H’, the impression ‘mp?’ elongated and curved upward in distal part; second tagma ‘Th’ 16.1 mm long, located behind ‘H’; ‘Th’ longer and thicker than ‘H’; ‘Th’ divided into three parts from front to back, their limits being determined by the positions of the legs and wings: first part, 3.2 mm long, appearing very short dorsally and carrying a pair of legs in its ventral part; second part, 7.3 mm long, very long and also carrying posteriorly a pair of legs and a pair of very long and wide structures (forewing tracks lfw and rfg); third part, 5.9 mm long, also very long, carrying one or two visible legs (only distal parts visible, their bases and femora being hidden by forewings) and a pair of hind wing tracks (lhw & rhw) quite distinct from forewing tracks, located just after level of bases of median legs; these wing structures being large, and covering at least 1/2 of total length of impression; third tagma impression ‘Abd’ the longest, 24.1 mm long, longer than ‘H’ and ‘Th’ combined, and of comparable thickness as ‘Th’, subdivided into a dorsal and a ventral parts; numerous indentations visible on it at fairly regular intervals (at least seven); no trace of dorsal or ventral appendages; a small structure ending in two points ‘app’ visible at apex of ‘Abd’.

-

Etymology. Dedicated to the wizard Radagast of the mythology of J.R.R. Tolkien (The Hobbit, 1937) who tames stick-insects in the adaptation of P. Jackson (The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, 2012).

Discussion

The impression most likely corresponds to a winged insect lying on its left side based on the presence of impressions of three tagmata with the anterior tagma much shorter than the two others and carrying structures that would correspond to antennae and possible mouthparts (mp) (Figs. 1a, 2); the median tagma corresponds to a thorax divided into a short prothorax bearing two legs, an elongated mesothorax with a pair of legs located anteriorly and a pair of wings located posteriorly, and a metathorax similar to the mesothorax, also carrying pairs of wings and legs; a segmented, elongated abdomen (Fig. 1c), legless and carrying a pair of complex terminal structures (cerci and/or ovipositor?) (Fig. 1b).

The ‘enlarged’ legs and inconspicuous joints between the thorax and legs indicate a certain viscosity of the substrate and possible weak motion of the legs. This could also be due to low movements of the substrate as indicated by the ripple marks. Most insects are fossilized in a dorsal or ventral position, especially paleopterans, but for the neopteran insects that hold their wings along the body, a lateral impression is possible. FBIs can remain unnoticed because of their shallow relief, requiring appropriate lighting to distinguish them. Here the delicate FBI is visible because the thin pelitic layer is exposed. The slab also has weak ripple-marks at the same level, showing a low-energy current and the presence of a biofilm25,26,27, which allowed the exceptional preservation of Phasmichnus. It is difficult to interpret the moment of life captured by this impression. This FBI probably corresponds to that of dying animal that was transported on fresh mud and laid its impression on it. The insect itself was probably destroyed later by the microbial activity. Evidence of such mats are frequent in the outcrop (folding of the mat, trace of grazing by organisms under the mat, etc.). Similar phenomena have been recorded in the late Jurassic lithographic limestone of Cerin, another well-known outcrop generated by microbial mats28.

No other known ichnotaxon of this size and shape can be brought closer to Phasmichnus gen. nov. Only Knecht et al.5 described an unnamed FBI of winged insect (attributed to an Ephemeropterida or a Plecoptera29,30,31) from the Late Carboniferous of the Massachusetts (USA), presenting an elongated body of comparable dimensions, but lacking distinct head and impressions of wings. It also preserves a possible cerci impression similar to that of Phasmichnus.

The position of the wings on the thorax and abdomen excludes the attribution of Phasmichnus gen. nov. to a Paleoptera because these have their wings unfolded over the body, except in the Diaphanopterodea, which have very different shorter and broader body shapes. The positions of the wing impressions of Phasmichnus exclude an attribution to the Ephemeropterida and Plecoptera and thus to the FBI described by Knecht et al.5. An Odonatoptera Archizygoptera or Zygoptera in which the wings may be lying on the body, especially in the case of a drowned individual with ‘wet’ wings, is conceivable. However, this attribution is unlikely because Odonatoptera have a highly modified thorax. Their short and reduced prothorax is followed posteriorly by a diamond-shaped structure as high as long and formed by the fusion of the meso- and metathorax32. Phasmichnus gen. nov. does not have a thorax of this type at all. We attribute it to a Neoptera capable of folding its wings over the abdomen. The presence of wings, the short prothorax plus the very elongated and narrow thorax and abdomen are only found in Phasmatodea among the extant insects, which also have the bases of their hind wings located behind the mesothoracic legs. This is indeed the case here. The other extant Neoptera have shorter abdomen and thorax in relation to their diameters, with the exception of the Mantophasmatodea, now apterous but whose ancestors were possibly winged. The extant and fossil Mantophasmatodea have the thoracic segments of nearly the same lengths, which is not the case here33. The Palaeozoic Caloneurodea also had narrow bodies but distinctly longer legs; and the Carboniferous Geraridae had an elongate prothorax and long legs, especially the hind legs that have enlarged femora, unlike Phasmichnus gen. nov34. The Late Carboniferous-Early Permian archaeorthopteran clade Cnemidolestidae had also elongate bodies with a relatively short prothorax, but they strongly differ from Phasmichnus gen. nov. in their very long and strong legs, especially the fore legs.

Extant stick insects, even the leaf-mimicking Phylliidae, differ from Phasmichnus gen. nov. in their shortened forewings, much shorter than the hind wings. But the Mesozoic winged representatives of the stem group Phasmatodea had fore- and hind wings of similar lengths, as in Phasmichnus gen. nov.15,17, possibly supporting its attribution to this lineage. Winged stick insects have their mid legs and forewings situated near the posterior margin of the elongate mesothorax as in Phasmichnus gen. nov.

Some molecular dating suggest that the Phasmatodea originated during the Middle Jurassic35,36, while recent paleontological discoveries show that the phasmid crown group was already well diversified at that time15,17. Triassic representatives of their stem group are known14, clearly more in accordance with more recent dating, viz. Permian-Triassic37, Middle Permian with confidence interval Carboniferous-end Permian38, or Carboniferous-Permian for stem group of Phasmatodea and Permian–Triassic for crown group39. The clade ((Mantophasmatodea + Grylloblattodea) + (Phasmatodea + Embioptera)) is considered as sister group of the Dictyoptera40, and therefore at least as old as the Carboniferous41. Thus, it is highly probable that representatives of the stem group of Phasmatodea or of the stem group of the clade ((Mantophasmatodea + Grylloblattodea) + (Phasmatodea + Embioptera)) existed in the Middle Permian. Furthermore, some Permian putative stem Embioptera have been described42, and an undescribed wing of an Embioptera was recently found in the Middle Permian of Southern China (Huang and Nel, in prep.), supporting the existence of stem group representatives of the two sister clades at that time. This would be in accordance to a putative attribution of the present discovery to the stem group Phasmatodea. Phasmichnus radagasti cannot be identified with certainty as a body impression of a stick insect sensu stricto as no anatomical features and no strict apomorphies of stick insects (e.g. fusions of first abdominal tergites and sternites with metathorax) are directly preserved, but it is an evidence of the presence of phasmatodean-like insects in the Middle Permian. A FBI is not a direct representation of the anatomy of the trackmaker: some anatomical structures may not have been imprinted and the overall impression may have undergone deformations, depending on the substrate43.

The typical morphology of Phasmatodea with narrow elongate bodies and elongate wings is clearly present in Phasmichnus. More precisely the general body and wing of Phasmichnus fits well with that of extant Tropidoderus childerni that has a very long body and hind wings and can hide itself in the vegetation with great efficiency (see internet site https://www.flickr.com/photos/petrichor/2177632362).

This type of morphology is consistent with adaptations to mimicry of elongated plant elements such as stems, branches or elongate leaves43, obviously present in the Permian vegetation and allowing concealing from predators. More generally, such narrow elongated body and wings are consistent with mimicry with plants among the extant terrestrial Neoptera (Mantodea, Heteroptera Reduviidae, Neuroptera Mantispidae, etc.), together with other functions such as predation.

The type of fossilization of Phasmichnus does not allow to find more information on this fossil. In particular, the possible pattern of coloration or details of ornamentations (spines, etc.), present in many extant stick insects and increasing the mimicry, are not available.

Several camouflages strategy are known among the late Carboniferous—Permian insects but they generally implicate disruptive strategies (spots and/or bands of different colors or even eyespots on wings). The archaeorthopteran family Cnemidolestidae shows an impressive diversity of such structures45. But plant mimicry is clearly less frequent during these periods. The orthopteran Permotettigonia is the only other case of a large leaf mimicry during the Middle Permian24. The strategy is different in Phasmichnus that would have imitated small branches and/or elongate leaves.

We found several slabs showing tetrapod tracks near Phasmichnus radagasti. The tetrapod ichnofauna of the type locality consists of small temnospondyl amphibians (Batrachichnus salamandroides), bolosaurian parareptiles (Varanopus isp.) and captorhinid eureptiles (Hyloidichnus bifurcatus). All these small vertebrates were probably insect hunters. Permotettigonia is the first accurate case of plant mimicry known in the Middle Permian of France24, Phasmichnus gen. nov. could be the second. The presence of a bio-mat could have been a large reserve of resources for the Hexapoda gathering on small water points and attracting the possible predators aforementioned. The trophic pressure of such potential predators in playa environments was possibly high enough to enable the rise of insects developing strategies of escape and/or plant-mimicry as early as the Middle Permian, in accordance with the opinion of Tihelka et al.39: ‘We recover a Permian to Triassic origin of crown Phasmatodea coinciding with the radiation of early insectivorous parareptiles, amphibians and synapsids’ [the only restriction to make to this sentence is that the Permian to Triassic stick insects did not belong to the crown but to the stem group of Phasmatodea]. Insectivorous synapsids and sauropsids, became very diverse in the Middle Permian46.

Material and methods

Preparation, observation and description

The holotype specimen was photographed with a Nikon D800 macro lens Micro Nikor 60/2,8 and drawn using Krita v.4.2.9 and PhotoFiltre 7 v.7.2.1. The nomenclature of Buatois et al.10 is followed to classify the types of arthropod tracks. The specimen was collected by one of us (RG).

Geological setting

The specimen was collected in the Gonfaron A site, located south-west of the Luc Basin in the Pelitic Formation47,48. The Pelitic Formation corresponds to the upper part of the Luc Basin stratigraphy47. It is currently dated to the Wordian thanks to ichnological studies47. This formation is characterised by red pelites with drying up facies (such as mudcracks) and ripplemarks suggesting shallow non-marine environments49. The Gonfaron A site is located in pelitic badlands (locally named ‘red earth’) on the edge of the Maures plain and topped by a Triassic cliff (Bundsandstein). Sedimentological data from the site indicate a floodplain environment of playa type (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information for a complete interpretation of the stratigraphy of the site). Several fossil arthropods have been found recently50. Others have been collected, also in the adjacent Permian basins and will be described later51.

References

Hunt, A. P. & Lucas, S. G. Tetrapod ichnofacies: A new paradigm. Ichnos 14, 59–68 (2007).

Voigt, S., Lucas, S. G. & Krainer, K. Coastal-plain origin of trace-fossil bearing red beds in the Early Permian of Southern New Mexico, USA. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 369, 323–334 (2013).

Mujal, E. et al. Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction and early Permian ichnoassemblage from the NE Iberian Peninsula (Pyrenean Basin). Geol. Mag. 153, 578–600 (2016).

Minter, N. J. & Braddy, S. J. Walking and jumping with Palaeozoic apterygote insects. Palaeontology 49, 827–835 (2006).

Knecht, R. J., Engel, M. S. & Benner, J. S. Late Carboniferous paleoichnology reveals the oldest full-body impression of a flying insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 6515–6519 (2011).

O’Brien, L. J., Braddy, S. J. & Radley, J. D. A new arthropod resting trace and associated suite of trace fossils from the Lower Jurassic of Warwickshire, England. Palaeontology 52, 1099–1112 (2009).

Dobler Lima, J. H., Netto, R. G., Corrêa, C. G. & Corrêa Lavina, E. L. Ichnology of deglaciation deposits from the Upper Carboniferous Rio do Sul Formation (Itararé Group, Parana Basin) at central-east Santa Catarina State (southern Brazil). J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 63, 137–148 (2015).

Lucas, S.G., Celeskey, M. & Sundstrom, M. Traces of a Permian seacoast: prehistoric Trackways. Natl. Monum. N. M. Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. 1–48 (2011).

Lucas, S. G., Lerner, A. J. & Voigt, S. Scorpionid resting trace from the Lower Permian of Southern New Mexico, USA. Ichnos 20, 195–201 (2013).

Buatois, L. A., Wisshak, M., Wilson, M. A. & Mángano, M. G. Categories of architectural designs in trace fossils: A measure of ichnodisparity. Earth Sci. Rev. 164, 102–181 (2017).

Jung, J., Huh, M. & Choi, B.-D. A comparative study on tracemaker of arthropod trace fossils in the Uhangri Formation, Haenam, Korea. J. Geol. Soc. Korea 56, 3–16 (2020).

Gorochov, A. V. Permian and Triassic walking sticks (Phasmatodea) from Eurasia. Paleontol. J. 28, 83–97 (1994).

Zompro, O. The Phasmatodea and Raptophasma n. gen., Orthoptera incertae sedis, in Baltic amber (Insecta: Orthoptera). Mitteilungen Geol. Paläontol. Inst. Univ. Hamburg 85, 229–261 (2001).

Nel, A., Marchal-Papier, F., Béthoux, O. & Gall, J. C. A ‘stick insect-like’ from the Triassic of the Vosges (France) (pre-Tertiary Phasmatodea). Annales Société entomologique France 40, 31–36 (2004).

Nel, A. & Delfosse, E. A new Chinese Mesozoic stick insect. Acta Paleontologica Polonica 56, 429–432 (2011).

Wedmann, S., Bradler, S. & Rust, J. The first fossil leaf insect: 47 million years of specialized cryptic morphology and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 565–569 (2007).

Shang, L., Béthoux, O. & Ren, D. New stem-Phasmatodea from the Middle Jurassic of China. Eur. J. Entomol. 108, 677–685 (2011).

Poinar, J.-R.G. A walking stick, Clonistria dominicana n. sp. (Phasmatodea: Diapheromeridae) in Dominican amber. Hist. Biol. 23, 223–226 (2011).

Tilgner, E. The fossil record of Phasmida (Insecta: Neoptera). Insect Syst. Evol. 31, 473–480 (2000).

Gorochov, A. V. Phasmomimidae: are they Orthoptera or Phasmatoptera?. Paleontol. J. 34, 295–300 (2000).

Nel, A., Prokop, J. & Ross, A. J. New genus of leaf-mimicking katydids (Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae) from the Late Eocene: Early Oligocene of France and England. C. R. Palevol 7, 211–216 (2008).

Wang, Y.-G. et al. Ancient pinnate leaf mimesis among lacewings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 16212–16215 (2010).

Shcherbakov, D. E. New and little-known families of Hemiptera Cicadomorpha from the Triassic of Central Asia: Early analogs of treehoppers and planthoppers. Zootaxa 2836, 1–26 (2011).

Garrouste, R. et al. Insect mimicry of plants dates back to the Permian. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–6 (2016).

Gall, J.-C. Les voiles microbiens. Leur contribution à la fossilisation des organismes au corps mou. Lethaia 23, 21–28 (1990).

Freytet, P., Lange-Badré, B., Barrier, P., Gand, G. & Montenat, C. L. fossilisation des empreintes de pattes et autres traces biologiques: Rôle du voile algaire et de la diagenèse précoce. Le Naturaliste Vendéen 3, 61–62 (2003).

Davies, N. S., Liu, A. G., Gibling, M. R. & Miller, R. F. Resolving MISS conceptions and misconceptions: a geological approach to sedimentary surface textures generated by microbial and abiotic processes. Earth Sci. Rev. 154, 210–246 (2016).

Gall, J.-C. et al. Influence du développement d’un voile algaire sur la sédimentation et la taphonomie des calcaires lithographiques Exemples du gisement de Cérin (Kimméridgien supérieur, Jura méridional français). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 2(301), 547–552 (1985).

Marden, J. H. Reanalysis and experimental evidence indicates that the earliest trace fossil of a winged insect was a surface-skimming neopteran. Evolution 67, 274–280 (2013).

Benner, J. S., Knecht, R. J. & Engel, M. S. Comment on Marden (2013): Reanalysis and experimental evidence indicate that the earliest trace fossil of a winged insect was a surface skimming neopteran. Evolution 67, 2142–2149 (2013).

Marden, J. H. Reply to Comment on Marden (2013) regarding the interpretation of the earliest trace fossil of a winged insect. Evolution 67, 2150–2153 (2013).

Nel, A., Bechly, G., Prokop, J., Béthoux, O. & Fleck, G. Systematics and evolution of Paleozoic and Mesozoic damselfly-like Odonaptera of the ‘Protozygopteran’ grade. J. Paleontol. 86, 81–104 (2012).

Huang, D.-Y., Nel, A., Zompro, O. & Waller, A. Mantophasmatodea now in the Jurassic. Naturwissenschaften 95, 947–952 (2008).

Béthoux, O. & Nel, A. Wing venation morphology and variability of Gerarus fischeri (Brongniart, 1885) sensu Burnham (Panorthoptera; Upper Carboniferous, Commentry, France), with inferences on flight performance. Org. Divers. Evol. 3, 173–183 (2003).

Misof, B. et al. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 346, 763–767 (2014).

Simon, S. et al. Old World and New World Phasmatodea: phylogenomics resolve the evolutionary history of stick and leaf insects. Front. Ecol. Evol. 7(345), 1–14 (2019).

Evangelista, D. A. et al. An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. (B) Biol. Sci. 286(20182076), 1–9 (2019).

Forni, G. et al. Phylomitogenomics provides new perspectives on the Euphasmatodea radiation (Insecta: Phasmatodea). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 155, 106983 (2020).

Tihelka, E., Cai, C., Giacomelli, M., Pisani, D. & Donoghue, P. C. J. Integrated phylogenomic and fossil evidence of stick and leaf insects (Phasmatodea) reveal a Permian- Triassic co-origination with insectivores. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7(201689), 1–12 (2020).

Wipfler, B. et al. Evolutionary history of Polyneoptera and its implications for our understanding of early winged insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 3024–3029 (2019).

Condamine, F. L., Nel, A., Grandcolas, P. & Legendre, F. Fossil and phylogenetic analyses reveal recurrent periods of diversification and extinction in dictyopteran insects. Cladistics 36, 394–412 (2020).

Shcherbakov, D. E. Permian and Triassic ancestors of webspinners (Embiodea). Rus. Entomol. J. 24, 187–200 (2015).

Marchetti, L. et al. Defining the morphological quality of fossil footprints. Problems and principles of preservation in tetrapod ichnology with examples from the Palaeozoic to the present. Earth Sci. Rev. 193, 109–145 (2019).

Bradler, S. & Buckley, T. R. Biodiversity of Phasmatodea. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, Volume II (eds Foottit, R. G. & Adler, P. H.) (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Nel, A. & Poschmann, M.J. A new representative of the ‘orthopteroid’ family Cnemidolestidae (Archaeorthoptera) from the Early Permian of Germany. Acta Palaeontol. Polonica, in press. (2021).

Steyer, J.S. La terre avant les dinosaures. Editions Belin – Pour la Science, 205 p. (2009).

Durand, M. The problem of the transition from the Permian to the Triassic Series in southeastern France: comparison with other Peritethyan regions. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 265, 281–296 (2006).

Gand, G. & Durand, M. Tetrapod footprint ichno-associations from French Permian basins. Comparisons with other Euramerican ichnofaunas. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 265, 157–177 (2006).

Demathieu, G., Gand, G. & Toutin-Morin, N. L. palichnofaune des bassins permiens provençaux. Geobios 25, 19–54 (1992).

Garrouste, R., Lapeyrie, J., Steyer, J.-S., Giner, S. & Nel, A. Insects in the Red Middle Permian of Southern France: First Protanisoptera (Odonatoptera) and new Caloneurodea (Panorthoptera), with biostratigraphical implications. Hist. Biol. 30, 546–553 (2018).

Garrouste, R., Nel, A. & Gand, G. New fossil arthropods (Notostraca and Insecta: Syntonopterida) in the Continental Middle Permian of Provence (Bas-Argens basin, France). C. R. Palevol 8, 49–57 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Mayor of Gonfaron for authorizations to collect fossils, the Maison de la Nature (Les Mayons) for accommodations, I. van Waveren (Natural History Museum Leiden), J. Fortuny (ICP, Barcelona), T. Arbez (Ottawa University), G. Lemaitre (Phylogenia Association) and the excavation team (M. Raymond, M. Ughetto, X. Pouly, V. Blondel, M. Denis) for their help on the field. This research was supported by the interdisciplinary programs RedPerm I and II, ATM (Action Thématique) MNHN, LabEx ANR-10-LABX-0003-BCDiv, ‘Investissements d’avenir’ ANR-11IDEX-0004-02 (Labex BCDiv ‘Diversite´Biologique et Culturelle’), Projet Fédérateur Department Origin and Evolution, set up by J-S.S., A.N. & R.G. This work in part of joint scientific project set up by J.S.S., A.N., and R.G. about palaeontology and palaeoichnology of the Permian Basins of South of France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. and A.N. described the specimen; R.G. and A.L. performed the morphometric analyses; J.-M.P., R.G., J.-S.S. and A.L. raised the stratigraphic log; A.L., A.N., R.G. and J.-S.S. prepared the manuscript; A.L. and V.N.-M. prepared the figures; R.G. discovered the fossil; J.-S.S. and R.G. jointly supervised this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Logghe, A., Nel, A., Steyer, JS. et al. A twig-like insect stuck in the Permian mud indicates early origin of an ecological strategy in Hexapoda evolution. Sci Rep 11, 20774 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00110-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00110-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.