Abstract

Swimming performance is a key feature that mediates fitness and survival in aquatic animals. Dispersal, habitat selection, predator–prey interactions and reproduction are processes that depend on swimming capabilities. Testing the critical swimming speed (Ucrit) of fish is the most straightforward method to assess their prolonged swimming performance. We analysed the contribution of several predictor variables (total body length, experimental water temperature, time step interval between velocity increments, species identity, taxonomic affiliation, native status, body shape and form factor) in explaining the variation of Ucrit, using linear models and random forests. We compiled in total 204 studies testing Ucrit of 35 inland fishes of the Iberian Peninsula, including 17 alien species that are non-native to that region. We found that body length is largely the most important predictor of Ucrit out of the eight tested variables, followed by family, time step interval and species identity. By contrast, form factor, temperature, body shape and native status were less important. Results showed a generally positive relationship between Ucrit and total body length, but regression slopes varied markedly among families and species. By contrast, linear models did not show significant differences between native and alien species. In conclusion, the present study provides a first comprehensive database of Ucrit in Iberian freshwater fish, which can be thus of considerable interest for habitat management and restoration plans. The resulting data represents a sound foundation to assess fish responses to hydrological alteration (e.g. water flow tolerance and dispersal capacities), or to categorize their habitat preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Swimming performance represents one of the most important features that mediate fitness and survival of fish and other aquatic animals1,2,3,4. It plays a crucial role in dispersal, migration, habitat selection, predator–prey interactions and reproduction5,6,7,8,9,10. Swimming performance in fish is traditionally assessed using swim tunnels and ecohydraulic flumes8,11,12,13,14,15 and can be classified into three categories: sustained, prolonged and burst swimming16. Sustained swimming is aerobically fueled and can be maintained for long time periods, typically more than 200 min, without muscular fatigue17,18,19. The maximum swimming speed of which fish are capable is burst swimming, which can be maintained only for shorter periods (typically < 20–30 s) and is fueled anaerobically16,19. Prolonged swimming is the transitional mode between sustained and burst swimming and is not barely distinguishable from burst swimming in some species19. Prolonged swimming is partly fueled by aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, and can be maintained for intermediate intervals of time (1–200 min)16,19.

Since Brett’s work20, many authors have opted for determining critical swimming speed (Ucrit), as a measurement of prolonged swimming performance, while measuring oxygen consumption rates at the same time21. To measure Ucrit, individual fish are forced to swim against water flow of increasing velocity until fatigue, i.e. the moment at which the fish can no longer swim and maintain its position in the current5,22.

Ucrit is well known to be positively related to body size, including both body length10,16 and body mass23,24. Swimming performance also depends on body shape25,26,27,28 and fin form8,25,29,30. For example, most of the fast-cruising fish have well streamlined bodies that reduce drag forces and recoil energy losses31. Muscle function32,33, swimming mode31,34,35, and fish behavior36 are also important factors that influence fish swimming performance. Thus, Ucrit is strongly size-dependent36 and specific to groups of species displaying similar swimming performances10,14. Ucrit is also known to depend on the experimental setups and, increases with shorter step-time intervals between velocity increments during the experiment37.

Previous studies have shown that abiotic factors, such as water temperature affect the Ucrit. In fact, a bell-shaped relationship between temperature and Ucrit has repeatedly been reported38,39,40. This means that Ucrit ascends as temperature rises below the optimum temperature and descends as temperature rises above the optimum temperature12,21. Nevertheless, some studies only detected significant decrease in swimming performance with lower water temperatures12,41. Similar bell-shaped relationships have also been observed between swimming speed and pH39 or salinity39,42,43,44,45. Other studies have noted the negative effects of several pollutants such as metals and nutrients on fish swimming performance37,39,46,47,48,49,50,51.

The demands of fish on locomotion in flowing water differ from those in still water as fish need to avoid downstream displacement in lotic environments such as rivers and streams52. In general, fish species that inhabit in fast flowing riverine habitats tend to show higher Ucrit than those that inhabit in slower flowing riverine or lentic habitats53,54. Because of the close relationship between habitat conditions and fish swimming performance, several studies have assessed Ucrit of species in different environments to understand the ecological consequences of anthropogenic perturbations in rivers such as hydrologic alteration, habitat fragmentation55, or navigation10, and to suggest corresponding mitigation measures. For example, Ucrit has commonly been used to estimate maximum flow velocities in fish passes that assist species to move up or downstream of barriers or that impede the spread of invasive species14,15,36,56,57.

The number of studies and the availability of data regarding Ucrit in fish have consistently grown in the last years14,36. However, many studies on fish swimming speeds have focused either on salmonids13 because of their commercial and recreational interest42,51,58,59, and on long-distance migratory fish such as potamodromous and diadromous species36,60. By contrast, studies evaluating Ucrit for many other species are rather limited61. This is particularly the case for many Mediterranean fish62, specifically for rare or local endemic species, which are frequently threatened63. Thus, general knowledge on the effects of factors such as body length and temperature on swimming performance in many of these Mediterranean fish species is lacking. Moreover, many regions in the world such as our study area, the Iberian Peninsula, are increasingly invaded by alien species. It has been shown that alien species replace the more flow-adapted native species in hydrologically altered systems64,65. However, the mechanisms by which the invasive species have competitive advantage over native species in calm, stagnant waters are still poorly understood. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the swimming capacities of both native and alien species may provide insights into the reasons of this replacement, which can be a result of great importance for the management of water bodies (e.g. habitat assessments of alien and native species, and development of efficient fish passages at physical or velocity barriers for native fish).

The objectives of this study are: (1) to compile the most comprehensive empirical dataset of Ucrit for Iberian freshwater fishes; (2) to compare the role of species identity, taxonomic affiliation, body length, body shape, time step interval between velocity increments and experimental temperature on Ucrit, using for the first time the machine learning technique ‘random forests’ (RF), and (3) to test for differences in Ucrit between native and alien species. We hypothesized that larger fish and more streamlined species would show higher Ucrit5 and that temperature would be one of the main factors that influence Ucrit39. Particular temperature effects are expected when experimental temperatures are beyond a species’ ecological thermal range. We also hypothesized that alien species would show weaker swimming performance than native fishes because many successful freshwater invaders in the Iberian Peninsula are considered limnophilic, i.e. preferring lentic habitats, compared to the more flow-adapted, often rheophilic native species64,65.

Results

The eight explanatory variables used in the RF model (i.e. species identity, family, fish total length [TL], body shape, form factor, time step interval, water temperature and native status) explained 72.8% of the variation in Ucrit. The most important explanatory variable out of the eight tested was TL (54.1% variable importance), followed by family (9.9%), time step interval (5.1%) and species identity (1.7%). Form factor (1.1%), temperature (0.4%), body shape (0.3%) and native status (0.2%) were of low importance (Fig. 1). Analysis of partial dependence of Ucrit on TL revealed a steady but nonlinear increase of Ucrit up to a body size TL ≤ 400 mm (Fig. S1) where it reached a plateau, since very few fish in the dataset were longer than 400 mm. In contrast, the partial dependence plot on time step intervals showed a decrease of Ucrit up to a time step interval ≤ 40 min (Fig. S2) where it stabilized. After accounting for fish body length and all other predictor variables, common roach (Rutilus rutilus), European bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), perch (Perca fluviatilis), zander (Sander lucioperca) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) displayed the highest Ucrit. By contrast, largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), European flounder (Platichthys flesus), channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Tagus and Douro nase (Pseudochondrostoma polylepis and P. duriense) and pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) showed the lowest Ucrit (Fig. 2).

Variable importance of predictors of Ucrit according to the random forest model. Variable importance is the difference in prediction accuracy (i.e. the number of observations classified correctly) before and after permuting a variable, averaged over all trees123; and represents the effect of a variable in both main effects and interactions. Total percentage of explained variation was 72.8%. Figure created using R120.

Partial dependence of Ucrit across fish species based on the random forest model. Figure created using R120.

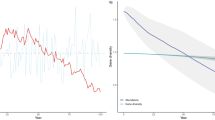

In the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, 84.6% of the variance was explained by the considered explanatory variables: TL, species identity, and their interaction, temperature and time step interval. The TL × species identity interaction was significant, i.e. the slopes of the Ucrit—TL relationship varied markedly among species (Table 1, Fig. 3), but was generally positive (approximately linear on a log–log scale) for species with significant relationships. In cyprinids for example, slope was flatter for common carp (Cyprinus carpio) than for roach (Fig. 3a, Table S1).The ANCOVA was in agreement with the RF model, showing that fish body length (i.e. log10 TL) and fish species identity (and its interaction with length) explained most of the variation in Ucrit (Table 1). In agreement also with the RF model, time step interval showed a significant negative effect on Ucrit. Temperature was much less important but significant in the linear model, whereas its quadratic term was not (Table 1). Figure 4 shows the relationship of Ucrit with TL and temperature for two common and well-studied fish species (roach and brown trout). Again, Ucrit showed an increase with fish body length, reaching its maximum at intermediate temperatures, as observed particularly in roach (Fig. 4a).

Relationship of Ucrit with fish total length (TL) across species belonging to: (a) Cyprinidae and Leuciscidae; (b) Salmonidae; (c) Percidae, Moronidae, Centrarchidae and Esocidae; and (d) other families. Only lines for significant regressions are shown (see Table S1 for statistics). Figure created using R120.

Surface plots relating Ucrit with fish total length (TL) and temperature for two well-studied species: (a) Rutilus rutilus, and (b) Salmo trutta. Note log10-transformations for Ucrit and TL variables. Figure created using R120.

The relationship between Ucrit and TL also varied notably among families, both in intercepts and slopes (Fig. S3, Tables S2 and S3). Cyprinids for example, displayed lower swimming performance than other families studied, especially for longer fish lengths. However, the model accounting for family explained about 1.6% less of the total variance compared to the model with species identity, because there was some variability among species within families, e.g. within cyprinids, leuciscids and salmonids (Fig. 3a,b).

A linear model with only body shape and TL but without species identity explained much less variation, despite being significant (Table S3). The slopes were also significantly different among groups of body shape with fusiform and elongated species showing higher swimming performance for a given length than species with eel-like and short and deep forms (Fig. S4). By contrast, native and alien species did not show significant differences (Fig. S5 and Table S3). The estimated marginal means (EMMs) revealed that (after controlling for length) zander, roach, perch and brown trout were the species with the highest Ucrit, whereas European flounder, eel, pumpkinseed and Spanish toothcarp (Aphanius iberus) showed the lowest Ucrit (Fig. S6). Comparing the EMMs and the partial dependence of Ucrit on species obtained with the RF model, we observed that both results were highly correlated (r = 0.680, Fig. S7) and showed no clear differences (mean difference = -2.19, 95% confidence interval = [-8.74, 4.36], Fig. S8).

Finally, the results of the linear mixed model (LMM) showed that fixed effects (TL, time step interval and water temperature) explained 50.5% of the variation (marginal R2), whereas the variation explained with the model also including random effects (species) increased up to 88.2% (conditional R2). This again highlights the differences in Ucrit among species and the heterogeneity of slopes of the Ucrit—length relationship. Overall, the LMM revealed a positive effect of TL (coef. = 0.604, SE = 0.072, P < 0.001, Fig. S9) and a negative effect of time step interval (coef. = -0.003, SE = 0.002, P = 0.004) on Ucrit. By contrast, the effect of temperature was statistically not clear in the LMM (coef. = 0.012, SE = 0.002, P = 0.987).

Discussion

This study is the first that comprehensively compiles and investigates a well-established measurement of prolonged swimming performance, i.e. critical swimming speed (Ucrit), for 35 freshwater fish species currently inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula. Our results reinforce the importance of several factors that influence Ucrit, with fish body length and taxonomic family being the most important predictors, followed by time step interval, species, the form factor, water temperature, species’ body shape and native status.

Analogously to previous studies, our results revealed that fish body length is a key biological factor to understand swimming performance9,14,16,36. It is well known that absolute critical swimming speed (Ucrit expressed in cm s−1) scales with fish body length66, as already described in earlier studies of sustained and prolonged swimming67. Furthermore, for many species Ucrit generally increases with the square root of fish length14,36. In our study, Ucrit scales with fish body length following the typical allometric equation or power function, which is generally estimated through linear regression of log-transformed variables:

where U is swimming speed and L is fish body length16. However, other studies also described the relationship with simple linear regressions without log-transformations66,68. Besides body length, it is important to note that body mass may also be an important predictor of Ucrit, especially when it comes to comparing swimming abilities among species with different body shapes, swimming and propulsion types8,16,69,70. Although not tested in this study, body mass is directly related to body volume and, therefore, to energy expenditure needed to move against the flow23,71. Moreover, energy costs of swimming (i.e. the amount of energy necessary to transport one unit of body mass per unit of distance) are negatively associated with body mass because of the lower surface area to volume ratio in larger fish72,73. Thus, the surface in contact with water per unit of volume is larger in small fish, increasing the friction drag and the relative dissipated energy31. In addition, there is a direct association between body volume and muscle mass and number of myofilaments, which favors swimming performance21. As expected, body shape significantly influenced fish swimming performance. Earlier studies showed that body shape also influences the energetic costs associated with swimming24,69,70. In general, streamlined fish tend to maximize thrust while minimizing drag and recoil energy losses72,74. Correspondingly, fish evolve body forms that enhance steady swimming (i.e. swimming at constant-speed in a straight line) in open-water habitats, high-flow environments, and areas with relatively high competition for patchily-distributed resources74. Steady swimming is generally enhanced with a streamlined body shape, a shallow caudal region and a high aspect ratio of the caudal fin75,76. In agreement with this, our results showed that elongated and fusiform body shapes are better adapted to swim steadily. On the other hand, species that present the opposite suite of morphological traits such as eel-like and short and deep bodies tend to optimize unsteady swimming (i.e. more complicated locomotor patterns in which changes in velocity or direction occur, such as fast-starts, rapid turns, braking, and burst-and-coast swimming)28.

Despite the general Ucrit – body length relationship, we found large variability among fish species as indicated by the significant interaction of TL and species identity and associated contrasting slopes. For example, we found that eastern mosquitofish has lower Ucrit than many other species for a given length, as shown in a previous study23. These differences might be due to fish species and populations having evolved over long-term periods, thereby adopting different abilities and strategies towards environmental and ecological conditions36. For example, a previous study showed that cyprinids living in fast flowing habitats showed higher Ucrit values compared to fish species preferring slow flowing waters, independently of phylogenetic relationships77. Other studies found that long-distance migratory fish show higher swimming capabilities than those migrating over shorter distances1. Moreover, other species adapted to a specific environment such as bottom-dwelling or flatfish species, usually perform poorly in Ucrit1,78,79. Consistent with these earlier findings, our results also indicated that benthic and flatfish species like European flounder have relatively lower Ucrit. In addition, our results revealed taxonomic family as a good predictor of Ucrit despite marked differences in lifestyle and form among species within the same family80. For example, in salmonids we revealed brown trout as a species with a high estimated Ucrit, while brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) showed comparably lower Ucrit for a given body length. These differences in swimming capacity might be related to differences in their habitat preferences with brook charr being generally found in slow-flowing pools whereas brown trout prefers faster riffle areas59. The relationships of habitat preferences and swimming capacity have also been shown in cyprinids and leuciscids because of their distribution in a wide variety of habitats and their associated morphological diversity77,80,81. However, we acknowledge that our analyses might have been affected by differences in data availability which might also affect the predictive power of the variable ‘species’.

In agreement with previous research, the duration of the step-test interval had an effect on mean critical velocity37. Ucrit increases for short time steps and reaches an asymptote at time step intervals between 30 and 60 minutes37, as we observed in our results. Thus, given these differences in swimming performance when using different time intervals, we therefore strongly recommend standardizing and carefully choosing the Ucrit protocol to prevent misleading understanding of fish swimming performances. In addition, we also examined the effects of temperature on Ucrit, which is also one of the most important abiotic factors influencing fish swimming performance72,82,83,84. Specifically, the relationship between Ucrit and temperature is commonly described by a bell-shaped curve39. Others demonstrated this bell-shaped relationship for juvenile sea bass, whose swimming speed increased as temperature rose from 15 to 25 °C and then decreased38. Mechanistically, this can be explained by a general decline of all physiological processes at low temperatures (e.g. a decrease in power generated by the muscle) that also reduces Ucrit13,39. As temperature increases, there is a positive effect on muscle functioning, and its associated power generation contributes to an increase in swimming performance85,86. Nevertheless, when temperature exceeds the optimum range, the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood decreases and restrains oxygen delivery to the tissues39. In contrast to this bell-shaped relationship of temperature and Ucrit, we only found a positive relationship with temperature. This lack of observed decline at high temperatures might be due to different reasons. On one hand, the bell-shaped curve is strongly influenced by rates of temperature acclimation previous to the experiment, being most marked in fishes that are exposed to intense temperature change, and increasingly less pronounced with acclimation time13. On the other hand, most experiments were conducted only at temperatures that are within the normal thermal tolerance range of a species, i.e. optimum or colder temperatures, rather than covering a long temperature gradient87. Finally, some studies revealed asymmetric relationships between temperature and Ucrit showing only significant swimming performance decreases at low temperatures12,41.

Our results revealed that both native and alien species have similar prolonged swimming performance, after accounting for body size. This finding is fairly surprising according to the apparent differences in habitat preferences between the two class of groups. Several studies showed that alien fish dominate Iberian reservoir habitats with their artificially stable limnological conditions88,89,90,91,92,93. By contrast, native species, mostly cypriniforms, are considered more adapted to lotic habitats with naturally more fluctuating flow regimes and, in particular, with frequent occurrence of high-flow events23,94,95,96. However, several invasive species that are often classified as limnophilic97 showed relatively high swimming capacities (e.g. zander, northern pike [Esox lucius], common bleak [Alburnus alburnus]). These species have in common that are pelagic and some of them also have high trophic level lifestyles, which has been shown to favor swimming performance and maximum aerobic capacity80. It suggests, therefore, that the classification of fish according to their habitat preferences is not always a good proxy of their prolonged swimming performance, and that Ucrit may be more related to ecological demands of species77. In addition, not all invasive fish of the Iberian Peninsula are inhabiting reservoirs or lentic habitats, as in the case of the non-native rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that rather prefer rivers with moderate to rapid flows98. Moreover, the native freshwater fish fauna of the Iberian Peninsula is characterized by a low number of families, but with a considerable degree of diversification of species98. Thus, it may be further hypothesized that the high diversity of species and forms could have counteracted the variation in Ucrit across species, independently of their origin (native or invasive). Ultimately, some invaders can colonize novel environments using other swimming strategies, like fast-start swimming99, and specific meso- or microhabitats. Thus, Ucrit might not be necessarily the main character determining ecological success and, therefore, invasiveness.

Our results might be limited by different issues. First, reported measurements of Ucrit might be skewed by experimental setups, such as the effects of chamber type and length. Indeed, it has been shown that fish can reach higher Ucrit values in longer flumes61,100,101,102. However, when taking data from different sources, we were not able to control for the effect of the flume characteristics on swimming performance measurements because they are often not reported. Second, small sample sizes and the narrow ranges of investigated fish lengths studied for some species might contribute to the large variability in regression line slopes found in this study. This was considered in our results and only provided significant regression lines (e.g. for species with larger sample sizes). Moreover, issues of data availability also affected the selection of predictors. For example, we were not able to analyze the effect of some variables like fish weight, which is often not provided in swimming performance studies, or habitat preference which is often rather unclear for the endemic species of the Iberian Peninsula97.

To sum up, this study showed that fish body length is the most relevant explanatory variable of Ucrit out of the eight considered predictor variables. Other important predictors were fish taxonomic affiliation (family and species identity) and the time step interval between velocity increments used during the experiment. Even though we found overall effects of body shape, form and water temperature on Ucrit, their relative importance as predictors were much lower. In contrast to our expectations, we did not find clear differences in Ucrit between native and alien fish species, after accounting for size. Therefore, this suggests that prolonged swimming performance might not be always related to the invasiveness of species in recipient ecosystems, although this needs further testing. We conclude that, besides advancing the fundamental understanding of prolonged swimming performance in Iberian freshwater fishes, our findings also provide the foundation to support their management. The compiled dataset comprises the so far most comprehensive information on Ucrit of the Iberian ichtyofauna. However, we note that swimming speed determined for fishes confined in a respirometer do not necessarily translate directly to free-swimming individuals in the field101 and thus should be used cautiously. However, until additional research is conducted on free-swimming fish, Ucrit data represent the best information available103. Thus, our results may be used as species-specific estimates of Ucrit: (i) to design fish bypasses estimating maximum allowable water velocities in order to improve river connectivity103, (ii) to develop barriers for the exclusion of invasive species14, (iii) to assess the effects of damming and hydrologic alteration on river fish, and (iv) to categorize fish habitat preferences and restrictions, since a species swimming performance might be a limiting factor of its presence in a given habitat.

Methods

Data compilation

We attempted to compile Ucrit data for all the current inland fish species inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula, including native and established alien species. The list of species mainly followed Doadrio et al.104 and Kottelat & Freyhof105 and was completed with few more recently described native species106 and alien species lately recorded107,108,109,110,111,112. Out of the 68 native and 32 alien naturalized inland fishes of the Iberian Peninsula, we found Ucrit data for 35 species (18 native and 17 alien), from 79 literature sources published from 1959 to 2020 (Table S4), which include data for 8 species (3 native and 5 alien) from our previous work23,24,70. Data extraction occasionally implied digitizing figures, using ImageJ2 software113, to estimate Ucrit values that were not provided in tables or within the text of the respective literature. We excluded works that investigated gradients or extreme values beyond the salinity or pH natural range of species, or that investigated the effect of pollution on swimming performance. In addition to Ucrit values, we collated eight additional explanatory variables for further analyses. Besides species identity, family and native status (native vs. alien), these included fish body length, body shape, body form factor, time step interval and water temperature as described for the experiments. We used body length rather than body mass due to better data availability. Ucrit and fish body length were converted to uniform units: relative Ucrit (BL s−1) was converted to absolute Ucrit (cm s−1); fork length (FL) or standard length (SL) were converted to total length (TL) using published length-length relationships114,115. We obtained the species-specific body shapes indicating whether a fish has a fusiform (i.e. spindle-shaped and streamlined body), elongated (i.e. tubular body), short and deep (i.e. almost circular and laterally compressed body), or eel-like form (i.e. long and snake-like body) from FishBase114. Finally, we calculated the species-specific body form factor (a3.0)75 using the parameters a and b of the weight-length relationship retrieved from FishBase using the following equation:

where S is the slope of the regression of log a vs. b. For cases of insufficient data on weight–length relationships to estimate S, we used the recommended mean value of −1.35875. The form factor is an estimate of the coefficient a if exponent b was 3. This form factor is commonly used to compare body shape differences among populations or species116,117 and increases from eel-like to elongated, fusiform and short and deep body shapes75. All the experiments considered were carried out at temperatures within a natural thermal range of each species. Raw data compiled are available at figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10260722).

Statistical analysis

We used random forest (RF)118, as implemented in the package “party”119 of the R software120, to analyze which of the six predictors best explained Ucrit. RF is a machine-learning technique that is frequently used because of their advantages, including computational efficiency on large databases with many correlated predictors, the provision of estimates of variable importance, the ability to impute missing data while maintaining accuracy, and the handling of non-linearities and interactions118,121. Specifically, RF computed with package “party” has the advantage of providing unbiased variable selection compared to other software packages, because it is more accurate when predictors are correlated and vary in their measurement scale or number of categories122,123. We used species identity, family, native status (native vs. introduced) and body shape (eel-like, elongated, fusiform or short and deep) as categorical factors, and TL, time step interval, water temperature and form factor as continuous predictors. In a first step, we searched for the optimal hyperparameters, i.e. number of trees (“ntree”) and number of variables per level (“mtry”) using the “mlr” R-package124. Consequently, we used 550 trees to build the RF as increasing the number of trees did not substantially affect the results of explained variation or variable importance125, and seven variables were randomly sampled as candidates at each split. We measured the percentage of variation explained (i.e. pseudo-R2) of the final model obtained. We used the conditional permutation scheme to estimate variable importance, which reflects the true impact of each predictor more reliably than a marginal approach123. For species, TL and time step interval, we generated partial dependence plots126 to graphically illustrate the conditional effect of a predictor while accounting for other predictors.

We used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to further investigate the effects and explanatory power of the predictors considered in the RF and to test for specific hypotheses. The general model included fish TL, species identity, and their interaction to test the assumption of homogeneous slopes in the standard ANCOVA127; time step interval and temperature and its quadratic term as predictors, since bell-shaped relationship is commonly accepted as the typical effect of temperature on Ucrit38,39. Another model included fish TL, species identity, time step interval, temperature and its quadratic term as predictors without considering interaction terms. Similarly to the RF-approach, we used the ANCOVA model to compute estimated marginal means (EMMs), using the “emmeans” package128,129, for the species identity factor and to compare the predicted Ucrit values with those obtained using RF. For that purpose, we applied the Bland–Altman analysis130, an established protocol for assessing agreement between two different measuring methods, using the “blandr” R package131. Specific hypotheses that we tested using ANCOVA were: whether there is an overall difference in Ucrit between (i) native and alien species, (ii) among families, and (iii) among body shape categories, after accounting for fish body length. We did not consider the length × factor interaction when it was clearly non-significant (P > 0.10) and thus used a standard ANCOVA in these cases127. In all models, TL and the response variable (Ucrit) were log10-transformed to satisfy the assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity and linearity.

Finally, we used a linear mixed model (LMM) accounting for species-specific differences using the R-package “lme4”132 to quantify the relative roles of species and other predictors and further test for heterogeneous slopes. We used Ucrit as response variable, TL, time step interval and temperature as fixed-effect covariates and species as random effects in a random slopes model. This approach allows each species to have different slopes, i.e. the covariates have different effects for each species. The random slopes model was selected over the random intercepts model due to lower AIC values (AIC = -147.3 and AIC = -124.6, respectively) and a significant likelihood ratio test (χ2 = 52.7, df = 15, P < 0.001). We also used the “ranova” function of the R-package “lmerTest”133 to test the random-effect terms in the model. Finally, we calculated p values and the marginal and conditional R2134,135,136,137 with the “lmerTest”133 and “MuMIn” R-packages134,135,136,137, respectively. The marginal R2 describes the variability explained by the fixed effects, while the conditional R2 describes the variability jointly explained by the fixed and the random effects.

Data availability

Critical swimming speed data underlying the analyses of this study are available as *.csv files via the figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10260722).

References

Tudorache, C., Viaene, P., Blust, R., Vereecken, H. & De Boeck, G. A comparison of swimming capacity and energy use in seven European freshwater fish species. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 17, 284–291 (2008).

Jones, D. R., Kiceniuk, J. W. & Bamford, O. S. Evaluation of the swimming performance of several fish species from the Mackenzie River. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 31, 1641–1647 (1974).

Burgess, E. A., Booth, D. T. & Lanyon, J. M. Swimming performance of hatchling green turtles is affected by incubation temperature. Coral Reefs 25, 341–349 (2006).

Watkins, T. B. Predator-mediated selection on burst swimming performance in tadpoles of the pacific tree frog, Pseudacris regilla. Physiol. Zool. 69, 154–167 (1996).

Kolok, A. S. Interindividual variation in the prolonged locomotor performance of ectothermic vertebrates: a comparison of fish and herpetofaunal methodologies and a brief review of the recent fish literature. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 700–710 (1999).

Reidy, S. P., Kerr, S. R. & Nelson, J. A. Aerobic and anaerobic swimming performance of individual Atlantic cod. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 347–357 (2000).

Taylor, E. B. & McPhail, J. D. Variation in burst and prolonged swimming performance among British Columbia populations of Coho Salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42, 2029–2033 (1985).

Videler, J. J. Fish Swimming (Chapman & Hall, London, 1993).

Plaut, I. Critical swimming speed: Its ecological relevance. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 131, 41–50 (2001).

Wolter, C. & Arlinghaus, R. Navigation impacts on freshwater fish assemblages: the ecological relevance of swimming performance. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 13, 63–89 (2003).

Wilson, R. W. & Egginton, S. Assessment of maximum sustainable swimming performance in rainbow trout. J. Exp. Biol. 192, 299–305 (1994).

Claireaux, G., Couturier, C. & Groison, A. Effect of temperature on maximum swimming speed and cost of transport in juvenile European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3420–3428 (2006).

McKenzie, D. J. & Claireaux, G. The effects of environmental factors on the physiology of aerobic exercise. in Fish Locomotion: An Eco-ethological Perspective (eds. Domenici, P. & Kapoor, B. G.) 296–332 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1201/b10190.

Katopodis, C. & Gervais, R. Fish swimming performance database and analyses. 2016/002, (DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2016/002. vi + 550 p., 2016).

Katopodis, C., Cai, L. & Johnson, D. Sturgeon survival: The role of swimming performance and fish passage research. Fish. Res. 212, 162–171 (2019).

Beamish, F. W. H. Swimming capacity. in Fish Physiology. Vol. VII. Locomotion. (eds. Hoar, W. S. & Randall, D. J.) 101–187 (1978).

Brett, J. R. Swimming performance of Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) in relation to fatigue time and temperature. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 24, 1731–1741 (1967).

Beamish, F. W. H. Swimming endurance of some Northwest Atlantic Fishes. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 23, 341–347 (1966).

Hoover, J. J., Zielinski, D. P. & Sorensen, P. W. Swimming performance of adult bighead carp Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (Richardson, 1845) and silver carp H. molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 33, 54–62 (2017).

Brett, J. R. The respiratory metabolism and swimming performance of young Sockeye Salmon. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 21, 1183–1226 (1964).

Hammer, C. Fatigue and exercise tests with fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 112, 1–20 (1995).

Beecham, R. V., Pearson, P. R., LaBarre, S. B. & Minchew, C. D. Swimming performance and metabolism of cultured golden shiners. N. Am. J. Aquac. 71, 59–63 (2009).

Srean, P., Almeida, D., Rubio-Gracia, F., Luo, Y. & García-Berthou, E. Effects of size and sex on swimming performance and metabolism of invasive mosquitofish Gambusia holbrooki. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 26, 424–433 (2016).

Rubio-Gracia, F. et al. Differences in swimming performance and energetic costs between an endangered native toothcarp (Aphanius iberus) and an invasive mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki). Ecol. Freshw. Fish 29, 230–240 (2020).

Webb, P. W. Form and function in fish swimming. Sci. Am. 251, 72–82 (1984).

Walker, J. A. Does a rigid body limit maneuverability?. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3391–3396 (2000).

Boily, P. & Magnan, P. Relationship between individual variation in morphological characters and swimming costs in brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) and yellow perch (Perca flavescens). J. Exp. Biol. 205, 1031–1036 (2002).

Webb, P. W. Body form, locomotion and foraging in aquatic vertebrates. Am. Zool. 24, 107–120 (1984).

Plaut, I. Effects of fish size on swimming performance, swimming behaviour and routine activity of Zebrafish Danio rerio. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 813–820 (2000).

Nicoletto, P. F. The relationship between male ornamentation and swimming performance in the guppy, Poecilia reticulata. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 28, 365–370 (1991).

Sfakiotakis, M., Lane, D. M. & Davies, J. B. C. Review of fish swimming modes for aquatic locomotion. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 24, 237–252 (1999).

Webb, P. W. & Weihs, D. Fish Biomechanics 398 (Praeger Publ., New York, 1983).

Kieffer, J. D. Limits to exhaustive exercise in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 126, 161–179 (2000).

Hertel, H. Structure, Form, Movement 251 (Reinhold Publishing Corp, New York, 1966).

Müller, U. K., Smit, J., Stamhuis, E. J. & Videler, J. J. How the body contributes to the wake in undulatory fish swimming: flow fields of a swimming eel (Anguilla anguilla). J. Exp. Biol. 204, 2751–2762 (2001).

Katopodis, C. & Gervais, R. Ecohydraulic analysis of fish fatigue data. River Res. Appl. 28, 444–456 (2012).

Peterson, R. H. Influence of Fenitrothion on Swimming Velocities of Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 31, 1757–1762 (1974).

Koumoundouros, G., Sfakianakis, D. G., Divanach, P. & Kentouri, M. Effect of temperature on swimming performance of sea bass juveniles. J. Fish Biol. 60, 923–932 (2002).

Randall, D. & Brauner, C. Effects of environmental factors on exercise in fish. J. Exp. Biol. 160, 113–126 (1991).

Oufiero, C. E. & Whitlow, K. R. The evolution of phenotypic plasticity in fish swimming. Curr. Zool. 62, 475–488 (2016).

Fangue, N. A., Mandic, M., Richards, J. G. & Schulte, P. M. Swimming performance and energetics as a function of temperature in Killifish Fundulus heteroclitus. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 81, 389–401 (2008).

Glova, G. J. & McInerney, J. E. Critical speeds of Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) fry to Smolt stages in relation to salinity and temperature. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 34, 151–154 (1977).

Yetsko, K. & Sancho, G. The effects of salinity on swimming performance of two estuarine fishes, Fundulus heteroclitus and Fundulus majalis. J. Fish Biol. 86, 827–833 (2015).

Nelson, J. A., Tang, Y. & Boutilier, R. G. The effects of salinity change on the exercise performance of two Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) populations inhabiting different environments. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 1295–1309 (1996).

Plaut, I. Resting metabolic rate, critical swimming speed, and routine activity of the euryhaline cyprinodontid, Aphanius dispar, acclimated to a wide range of salinities. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 73, 590–596 (2000).

Howard, T. E. Swimming performance of Juvenile Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) exposed to bleached Kraft Pulpmill Effluent. J. Fish. Res. Board Canada 32, 789–793 (1975).

Nikl, D. L. & Farrell, A. P. Reduced swimming performance and gill structural changes in juvenile salmonids exposed to 2-(thiocyanomethylthio)benzothiazole. Aquat. Toxicol. 27, 245–263 (1993).

Brown, D. R., Thompson, J., Chernick, M., Hinton, D. E. & Di Giulio, R. T. Later life swimming performance and persistent heart damage following subteratogenic PAH mixture exposure in the Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36, 3246–3253 (2017).

Beaumont, M. W., Butler, P. J. & Taylor, E. W. Exposure of brown trout, Salmo trutta, to sub-lethal copper concentrations in soft acidic water and its effect upon sustained swimming performance. Aquat. Toxicol. 33, 45–63 (1995).

Beaumont, M. W., Butler, P. J. & Taylor, E. W. Plasma ammonia concentration in brown trout in soft acidic water and its relationship to decreased swimming performance. J. Exp. Biol. 198, 2213–2220 (1995).

Shingles, A. et al. Effects of sublethal ammonia exposure on swimming performance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Exp. Biol. 204, 2691–2698 (2001).

McGuigan, K., Franklin, C. E., Moritz, C. & Blows, M. W. Adaptation of rainbow fish to lake and stream habitats. Evolution (NY) 57, 104–118 (2003).

Leavy, T. R. & Bonner, T. H. Relationships among swimming ability, current velocity association, and morphology for freshwater lotic fishes. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 29, 72–83 (2009).

Langerhans, R. B. Predictability of phenotypic differentiation across flow regimes in fishes. Integr. Comp. Biol. 48, 750–768 (2008).

Toepfer, C. S., Fisher, W. L. & Haubelt, J. A. Swimming performance of the threatened leopard darter in relation to road culverts. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 128, 155–161 (1999).

Peake, S. J. Behavior and passage performance of northern pike, walleyes, and white suckers in an experimental raceway. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 28, 321–327 (2008).

Katopodis, C. Developing a toolkit for fish passage, ecological flow management and fish habitat works. J. Hydraul. Res. 43, 451–467 (2005).

Booth, R. K., Scott McKinley, R., Økland, F. & Sisak, M. M. In situ measurement of swimming performance of wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) using radio transmitted electromyogram signals. Aquat. Living Resour. 10, 213–219 (1997).

Peake, S., McKinley, R. S. & Scruton, D. A. Swimming performance of various freshwater Newfoundland salmonids relative to habitat selection and fishway design. J. Fish Biol. 51, 710–723 (1997).

Silva, A. T. et al. The future of fish passage science, engineering, and practice. Fish Fish. 19, 340–362 (2018).

Haro, A., Castro-Santos, T., Noreika, J. & Odeh, M. Swimming performance of upstream migrant fishes in open-channel flow: a new approach to predicting passage through velocity barriers. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 61, 1590–1601 (2004).

Alexandre, C. M., Branca, R., Quintella, B. R. & Almeida, P. R. Critical swimming speed of the southern straight-mouth nase Pseudochondrostoma willkommii (Steindachner, 1866), a potamodromous cyprinid from southern Europe. Limnetica 35, 365–372 (2016).

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019-1. (2019). Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed: 6 May 2019)

Boix, D. et al. Response of community structure to sustained drought in Mediterranean rivers. J. Hydrol. 383, 135–146 (2010).

Bae, M. J., Murphy, C. A. & García-Berthou, E. Temperature and hydrologic alteration predict the spread of invasive Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Sci. Total Environ. 639, 58–66 (2018).

Mateus, C. S., Quintella, B. R. & Almeida, P. R. The critical swimming speed of Iberian barbel Barbus bocagei in relation to size and sex. J. Fish Biol. 73, 1783–1789 (2008).

Thompson, D. W. On growth and Form (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1917).

Romão, F., Quintella, B. R., Pereira, T. J. & Almeida, P. R. Swimming performance of two Iberian cyprinids: the Tagus nase Pseudochondrostoma polylepis (Steindachner, 1864) and the bordallo Squalius carolitertii (Doadrio, 1988). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 28, 26–30 (2012).

Ohlberger, J., Staaks, G. & Hölker, F. Swimming efficiency and the influence of morphology on swimming costs in fishes. J. Comp. Physiol. B Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 176, 17–25 (2006).

Rubio-Gracia, F., García-Berthou, E., Guasch, H., Zamora, L. & Vila-Gispert, A. Size-related effects and the influence of metabolic traits and morphology on swimming performance in fish. Curr. Zool. 1–11 (2020).

Ohlberger, J., Staaks, G., Van Dijk, P. L. M. & Hölker, F. Modelling energetic costs of fish swimming. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Comp. Exp. Biol. 303, 657–664 (2005).

Webb, P. W. Hydrodynamics and energetics of fish propulsion. Bull. Fish Res. Board Canada 190, 1–159 (1975).

Schmidt-Nielsen, K. Locomotion: energy cost of swimming, flying, and running. Science (80.-) 177, 222–228 (1972).

Langerhans, R. B. & Reznick, D. N. Ecology and Evolution of Swimming Performance in Fishes: Predicting Evolution with Biomechanics. Fish Locomotion: an ethoecological perspective (Oxford, 2010).

Froese, R. Cube law, condition factor and weight-length relationships: History, meta-analysis and recommendations. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 22, 241–253 (2006).

Weihs, D. Optimal fish cruising speed. Nature 245, 48–50 (1973).

Fu, S. J. et al. Interspecific variation in hypoxia tolerance, swimming performance and plasticity in cyprinids that prefer different habitats. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 590–597 (2014).

Knaepkens, G., Maerten, E. & Eens, M. Performance of a pool-and-weir fish pass for small bottom-dwelling freshwater fish species in a regulated lowland river. Anim. Biol. 57, 423–432 (2007).

Duthie, G. G. The respiratory metabolism of temperature-adapted flatfish at rest and during swimming activity and the use of anaerobic metabolism at moderate swimming speeds. J. Exp. Biol. 97, 359–373 (1982).

Killen, S. S. et al. Ecological influences and morphological correlates of resting and maximal metabolic rates across teleost fish species. Am. Nat. 187, 592–606 (2016).

Schönhuth, S., Vukić, J., Šanda, R., Yang, L. & Mayden, R. L. Phylogenetic relationships and classification of the Holarctic family Leuciscidae (Cypriniformes: Cyprinoidei). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 127, 781–799 (2018).

Fry, F. E. J. The effects of the environment on animal activity. Publ. Ontario Fish. Res. Lab. 68, 1–62 (1947).

Fry, F. E. J. The effect of environmental factors on the physiology of fish. in Fish Physiology. Vol. VI. Environmental Relations and Behavior (eds. Hoar, W. S. & Randall, D. J.) (1971).

Brett, J. R. Energetic responses of salmon to temperature. A study of some thermal relations in the physiology and freshwater ecology of Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Am. Zool. 11, 99–113 (1971).

Johnston, I. A. & Temple, G. K. Thermal plasticity of skeletal muscle phenotype in ectothermic vertebrates and its significance for locomotory behaviour. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2305–2322 (2002).

Rome, L. C. The effect of temperature and thermal acclimation on the sustainable performance of swimming scup. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 362, 1995–2016 (2007).

Videler, J. J. & Wardle, C. S. Fish swimming stride by stride: speed limits and endurance. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1, 23–40 (1991).

Aparicio, E., Vargas, M. J., Olmo, J. M. & de Sostoa, A. Decline of native freshwater fishes in a Mediterranean watershed on the Iberian Peninsula: a quantitative assessment. Environ. Biol. Fishes 59, 11–19 (2000).

Leunda, P. M. Impacts of non-native fishes on Iberian freshwater ichthyofauna: current knowledge and gaps. Aquat. Invasions 5, 239–262 (2010).

Carol, J. et al. The effects of limnological features on fish assemblages of 14 Spanish reservoirs. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 15, 66–77 (2006).

Clavero, M., Blanco-Garrido, F. & Prenda, J. Fish fauna in Iberian Mediterranean river basins: biodiversity, introduced species and damming impacts. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 14, 575–585 (2004).

Corbacho, C. & Sánchez, J. M. Patterns of species richness and introduced species in native freshwater fish faunas of a mediterranean-type basin: the Guadiana river (Southwest Iberian Peninsula). River Res. Appl. 17, 699–707 (2001).

Rodríguez-Ruiz, A. Fish species composition before and after construction of a reservoir on the Guadalete River (SW Spain). Arch. Hydrobiol. 142, 353–369 (1998).

Propst, D. L. & Gido, K. B. Responses of native and nonnative fishes to natural flow regime mimicry in the San Juan River. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 133, 922–931 (2004).

Gido, K. B., Propst, D. L., Olden, J. D. & Bestgen, K. R. Multidecadal responses of native and introduced fishes to natural and altered flow regimes in the American Southwest. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 70, 554–564 (2013).

Pool, T. K. & Olden, J. D. Assessing long-term fish responses and short-term solutions to flow regulation in a dryland river basin. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 24, 56–66 (2015).

Cano-Barbacil, C., Radinger, J. & García-Berthou, E. Reliability analysis of fish traits reveals discrepancies among databases. Freshw. Biol. 65, 863–877 (2020).

Doadrio, I. Atlas y Libro Rojo de los Peces Continentales de España. (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, 2001).

Tierney, K. B., Kasurak, A. V., Zielinski, B. S. & Higgs, D. M. Swimming performance and invasion potential of the round goby. Environ. Biol. Fishes 92, 491–502 (2011).

Tudorache, C., Viaenen, P., Blust, R. & De Boeck, G. Longer flumes increase critical swimming speeds by increasing burst-glide swimming duration in carp Cyprinus carpio L. J. Fish Biol. 71, 1630–1638 (2007).

Peake, S. J. & Farrell, A. P. Fatigue is a behavioural response in respirometer-confined smallmouth bass. J. Fish Biol. 68, 1742–1755 (2006).

Kern, P., Cramp, R. L., Gordos, M. A., Watson, J. R. & Franklin, C. E. Measuring Ucrit and endurance: equipment choice influences estimates of fish swimming performance. J. Fish Biol. 92, 237–247 (2018).

Peake, S. J. Swimming performance and behavior of fish species endemic to Newfoundland and Labrador: a literature review for the purpose of establishing design and water velocity criteria for fishways and culverts. Can. Manuscr. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2843, 1–52 (2008).

Doadrio, I., Perea, S., Garzón-Heydt, P. & González, J. L. Ictiofauna continental española. Bases para su seguimiento. (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino, 2011).

Kottelat, M. & Freyhof, J. Handbook of European freshwater fishes. (Publications Kottelat, 2007).

Mateus, C. S., Alves, M. J., Quintella, B. R. & Almeida, P. R. Three new cryptic species of the lamprey genus Lampetra Bonnaterre, 1788 (Petromyzontiformes: Petromyzontidae) from the Iberian Peninsula. Contrib. Zool. 82, 37–53 (2013).

Benejam, L., Carol, J., Alcaraz, C. & García-Berthou, E. First record of the common bream (Abramis brama) introduced to the Iberian Peninsula. Limnetica 24, 273–274 (2005).

López, V. et al. Atles dels peixos del delta de l’Ebre. (Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament d’Agricultura, Ramaderia, Pesca i Medi Natural. Parc Natural del Delta de l’Ebre., 2012).

Merciai, R. et al. First record of the asp Leuciscus aspius introduced into the Iberian Peninsula. Limnetica 37, 341–344 (2018).

Aparicio, E. First record of a self-sustaining population of Alpine charr Salvelinus umbla (Linnaeus, 1758). Graellsia 71, 1–3 (2015).

Aparicio, E., Carmona-Catot, G., Kottelat, M., Perea, S. & Doadrio, I. Identification of Gobio populations in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula: first record of the non-native Languedoc gudgeon Gobio occitaniae (Teleostei, Cyprinidae). BioInvas. Rec. 2, 163–166 (2013).

Ribeiro, F., Rylková, K., Moreno-Valcárcel, R., Carrapato, C. & Kalous, L. Prussian carp Carassius gibelio: a silent invader arriving to the Iberian Peninsula. Aquat. Ecol. 49, 99–104 (2015).

Rueden, C. T. et al. Image J2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 1–26 (2017).

FishBase. (2019).

Ramseyer, L. J. Total Length to fork length relationships of Juvenile Hatchery-reared Coho and Chinook Salmon. Progress. Fish-Culturist 57, 250–251 (1995).

Verreycken, H., Van Thuyne, G. & Belpaire, C. Length-weight relationships of 40 freshwater fish species from two decades of monitoring in Flanders (Belgium). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 27, 1416–1421 (2011).

Neat, F. C. & Campbell, N. Proliferation of elongate fishes in the deep sea. J. Fish Biol. 83, 1576–1591 (2013).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Hothorn, T., Hornik, K. & Zeileis, A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 15, 651–674 (2006).

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2020).

Tuulaikhuu, B. A., Guasch, H. & García-Berthou, E. Examining predictors of chemical toxicity in freshwater fish using the random forest technique. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 10172–10181 (2017).

Strobl, C., Boulesteix, A.-L., Zeileis, A. & Hothorn, T. Bias in random forest variable importance measures: Illustrations, sources and a solution. BMC Bioinform. 8, 1–25 (2007).

Strobl, C., Boulesteix, A.-L., Kneib, T., Augustin, T. & Zeileis, A. Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinform. 9, 307 (2008).

Bischl, B. et al. mlr: machine learning in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–5 (2016).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by random forest. R news 2, 18–22 (2002).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

García-Berthou, E. & Moreno-Amich, R. Multivariate analysis of covariance in morphometric studies of the reproductive cycle. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 50, 1394–1399 (1993).

Searle, S. R., Speed, F. M. & Milliken, G. A. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least squares means. Am. Stat. 34, 216–221 (1980).

Lenth, R. Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (2018).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 8, 307–310 (1986).

Datta, D. blandr: a Bland-Altman Method Comparison package for R. (Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.824514, https://github.com/deepankardatta/blandr, 2017).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Barton, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. (2018).

Johnson, P. C. D. Extension of Nakagawa & Schielzeth’s R2GLMM to random slopes models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 944–946 (2014).

Nakagawa, S. & Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 133–142 (2013).

Nakagawa, S., Johnson, P. C. & Schielzeth, H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 1–11 (2017).

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (project CGL2016‐80820-R, AEI/FEDER/EU). Further funding support was provided by the 2015-2016 BiodivERsA COFUND call and the Spanish Ministry of Science (project ODYSSEUS, BiodivERsA3-2015-26, PCIN-2016-168, RED2018‐102571‐T, and PID2019-103936GB-C21) and the Government of Catalonia (ref. 2017 SGR 548). CCB, MA, and FRG benefitted from pre-doctoral fellowships of the Spanish Ministry of Science (ref. BES-2017-081999), the Government of Catalonia (FI 2016 Gencat), and the University of Girona (IFUdG17), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EGB and AVG devised the study. CCB, MA, FRG and AVG compiled the data. Statistical analyses were carried out by CCB with specific assistance from JR and EGB. CCB wrote the original draft, and all authors commented on and contributed to revising the draft versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cano-Barbacil, C., Radinger, J., Argudo, M. et al. Key factors explaining critical swimming speed in freshwater fish: a review and statistical analysis for Iberian species. Sci Rep 10, 18947 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75974-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75974-x

This article is cited by

-

Survival, healing, and swim performance of juvenile migratory sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) implanted with a new acoustic microtransmitter designed for small eel-like fishes

Animal Biotelemetry (2023)

-

A review and meta-analysis of the environmental biology of bleak Alburnus alburnus in its native and introduced ranges, with reflections on its invasiveness

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (2023)

-

Fish body geometry reduces the upstream velocity profile in subcritical flowing waters

Aquatic Sciences (2022)

-

Pre-reproductive movements of potamodromous cyprinids in the Iberian Peninsula: when environmental variability meets semipermeable barriers

Hydrobiologia (2022)

-

Individual differences in dominance-related traits drive dispersal and settlement in hatchery-reared juvenile brown trout

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.