Abstract

Fluorescent natural organic matter at tryptophan-like (TLF) and humic-like fluorescence (HLF) peaks is associated with the presence and enumeration of faecal indicator bacteria in groundwater. We hypothesise, however, that it is predominantly extracellular material that fluoresces at these wavelengths, not bacterial cells. We quantified total (unfiltered) and extracellular (filtered at < 0.22 µm) TLF and HLF in 140 groundwater sources across a range of urban population densities in Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, and Uganda. Where changes in fluorescence occurred following filtration they were correlated with potential controlling variables. A significant reduction in TLF following filtration (ΔTLF) was observed across the entire dataset, although the majority of the signal remained and thus considered extracellular (median 96.9%). ΔTLF was only significant in more urbanised study areas where TLF was greatest. Beneath Dakar, Senegal, ΔTLF was significantly correlated to total bacterial cells (ρs 0.51). No significant change in HLF following filtration across all data indicates these fluorophores are extracellular. Our results suggest that TLF and HLF are more mobile than faecal indicator bacteria and larger pathogens in groundwater, as the predominantly extracellular fluorophores are less prone to straining. Consequently, TLF/HLF are more precautionary indicators of microbial risks than faecal indicator bacteria in groundwater-derived drinking water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a rapid, reagentless technique used to characterise fluorescent natural organic matter (OM) in water1,2,3,4,5,6,7. There is substantial evidence that natural waters contaminated with wastewater display enhanced fluorescent OM8,9,10,11,12,13,14. This property led to the suggestion that fluorescence spectroscopy could be an early-warning indicator for the wastewater contamination of drinking water15.

Multiple studies have now demonstrated strong associations between the presence and enumeration of thermotolerant coliform (TTCs), or specifically Escherichia coli, and fluorescent OM peaks in groundwater-derived drinking water16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The associated OM peaks are tryptophan-like fluorescence (TLF) and humic-like fluorescence (HLF) that occur at excitation/emission wavelengths pairs of 280/350 and 320–360/400–480 nm, respectively, and can be quantified instantaneously in-situ with portable fluorimeters.

A wide range of studies demonstrating relationships between TLF/HLF and TTCs may indicate fluorescence is emitted by fluorophores within bacteria cells. Indeed, Fox et al.23 noted that at least 75% of TLF produced from E. coli cells cultured in the laboratory was intracellular in nature. However, E. coli is the favoured organism for the industrial production of tryptophan24 and can also excrete indole that also fluoresces within the TLF region22,25.

In an assortment of surface waters, Baker et al.26 showed 32–86% of TLF was lost following filtration through a 0.2 µm membrane indicating a substantial proportion was associated with particulate and cellular material. They also suggested HLF was mainly as dissolved humic material and showed little change following filtration with 70–96% of the signal remaining after filtration. Samples from the River Leith, NW England, in an area featuring groundwater–surface interaction showed a slightly lower TLF loss following filtration of 20–40%27, albeit through a larger pore-size 0.45 µm membrane that would not remove all microbes. In groundwater, we might expect an even higher proportion of TLF and HLF to be extracellular due to natural filtration during recharge and subsurface flow, as well as, typically, a lower microbial biomass28,29,30,31. This expectation would have implications for TLF/HLF use as faecal indicators in groundwater, which provides the majority of the global drinking water supply.

We hypothesise that TLF and HLF are primarily extracellular within groundwater. Previously, we undertook a pilot investigation of 30 groundwater supplies in rural India and revealed a median of 86% of TLF was extracellular20. We further examine this hypothesis by evaluating the extracellular nature of TLF, as well as HLF for the first time, in a larger groundwater dataset from four countries with contrasting hydrogeological settings and pollution pressures.

Materials and methods

Study areas

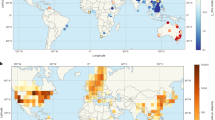

The four study areas together comprise varying degrees of urbanisation from a large city to rural context where pollution sources and pressures vary considerably. Dakar is the large capital city of Senegal with over three million inhabitants constrained within the Cap-Vert peninsular, Kisumu is a medium-sized city of 600,000 residents in Kenya, Lukaya is a small town of around 24,000 people in Uganda, and the rural communities were located in the Lilongwe & Balaka Districts of Malawi (Fig. 1).

modified from https://online.seterra.com/pdf/africa-countries.pdf.

Study site locations in Africa. Continental map

The four study areas have contrasting hydrogeological settings. The unconfined shallow Thiaroye aquifer of Dakar comprises Quaternary fine- and medium-grained sands with a shallow water table less than 2 m below ground level (bgl)32,33,34. The heterogeneous volcano-sedimentary Kisumu aquifer system is a suite of Archaean age metasediments, Tertiary volcanics, Quaternary sediments, colluvium and lateritic soils35,36,37. It is multi-layered with unconfined (5–30 m) and confined (> 30 m) horizons. Lukaya predominantly sits on Precambrian Basement with aquifers developed within the weathered overburden and fractured bedrock, in addition to alluvial aquifers towards Lake Victoria. Rest water levels are between 0.5 and 9 m bgl. Lilongwe District is Precambrian Basement with deeper rest water levels between 15 and 25 m bgl38. The alluvial aquifers in Balaka District are dominated by clays with significant subordinate sand horizons and a typical rest water level of 5–10 m bgl38. Sanitation in all the study areas consists of mainly onsite sanitation39,40,41,42, which has the potential to faecally contaminate underlying groundwater resources that are used by communities in all settings20.

Groundwater sampling and analysis

A total of 140 groundwater sources were sampled: 29 in Dakar, 38 in Kisumu, 32 in Lukaya, and 41 in Lilongwe & Balaka Districts. Sampling was undertaken in the dry season in Dakar and Kisumu and the wet season in Lukaya and Lilongwe & Balaka Districts. The sources comprised a mixture of pumped boreholes, hand pumped boreholes, open wells, and springs. Samples were obtained from open wells using a 12 V submersible WaSP-P5 pump, except for Lilongwe & Balaka Districts where a rope and bucket were used. Prior to sampling, boreholes, open wells (except Lilongwe & Balaka Districts) and hand pumps flowed for at least 1–2 min to ensure pipework was flushed and the sample was representative of the source. Springs were sampled directly from the outlet: either a discharge pipe in a protected setting or from the surface water channel in an unprotected setting.

TLF was determined using a portable UviLux fluorimeter targeting the excitation–emission peak at λex 280 ± 15 nm and λem 360 ± 27.5 nm (Chelsea Technologies Ltd, UK). HLF in Dakar and Lukaya was quantified by a UviLux fluorimeter configured at an excitation–emission peak at λex 280 ± 15 nm and λem 450 ± 27.5 nm (Chelsea Technologies Ltd, UK). This fluorimeter did not target the centres of the HLF peaks, but was aligned at the same excitation as TLF because of the optical overlap between the TLF and HLF regions. Laboratory calibrations were implemented for all fluorescence measurements, which report quinine sulphate units (QSU) where 1 QSU is equivalent to 1 ppb quinine sulphate dissolved in 0.105 M perchloric acid. Fluorescence analysis was conducted in a HDPE beaker placed within a covered black container to prevent interference from sunlight. Analysis was conducted on unfiltered water to indicate total fluorescence, then passed through a low-protein binding 0.22 µm PVDF membrane (Sterivex, Merck KGaQ, Germany) to sterilise the water and quantify extracellular fluorescence.

Repeatability of TLF fluorimeter data was previously investigated in the laboratory using dissolved tryptophan standards18. This study indicated that repeatability was approximately 0.2–0.6 QSU up to 100 QSU, with evidence that absolute repeatability decreased with increasing intensity. To address repeatability in a field situation, including HLF, we calculated 3σ of 74 duplicated measurements in Lukaya. These data ranged between 0–16.5 and 0–49.2 QSU for TLF and HLF, respectively. Repeatability was 0.5 QSU for TLF and 0.3 QSU for HLF.

Specific electric conductivity (SEC), pH, temperature and turbidity were quantified using multiparameter Manta-2 sondes (Eureka Waterprobes, USA) in Dakar, Kisumu, and Lukaya. In Lilongwe & Balaka Districts, temperature, SEC, and turbidity were measured using a HI766EIE1 thermocouple with HI935005 thermometer (Hanna Instruments, USA), S3 portable conductivity meter (METTLER TOLEDO, USA), and 2100Q turbidimeter (Hach Company, USA), respectively.

Thermotolerant coliform (TTC) samples were collected in sterile 250 mL polypropylene bottles and stored in a cool box (up to 8 h) before analysis18. TTCs were isolated and enumerated using the membrane filtration method with Membrane Lauryl Sulphate Broth (MLSB, Oxoid Ltd, UK) as the selective medium. Between 0.1 and 100 mL of sample was passed through a 0.45 µm cellulose nitrate membrane (GE Whatman, UK) to ensure colonies were not too numerous to count, whilst maintaining a limit of detection of 1 cfu/100 mL. The membrane was placed on an absorbent pad (Pall Gelman, Germany) saturated with MLSB broth in a plate and incubated at 44 °C for 18–23 h. Plates were examined within 15 min of removal from the incubator and all cream to yellow colonies greater than 1 mm counted as TTCs.

Samples in Dakar and Lukaya for total (planktonic) bacterial cells were collected in 4.5 mL polypropylene cryovials (STARLAB, UK) that were pre-treated with the preservative glutaraldehyde and the surfactant Pluronic F6843 at final concentrations of 1% and 0.01%, respectively. The samples were frozen at − 18 °C within 8 h of collection, defrosted overnight during transit to the UK, and analysed the following morning on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer equipped with a 488 nm solid state laser (Becton Dickinson UK Ltd, UK). Water samples (500 mL) were stained with SYBR Green I (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) at a final concentration of 0.5% for 20 min in the dark at room temperature, before running on the Accuri at a slow flow rate (14 mL/min, 10 mm core) for 5 min and a detection threshold of 1,500 on channel FL121. A single manually drawn gate was created to discriminate bacterial cells from particulate background, and cells per mL were calculated using the total cell count in 5 min divided by the reported volume run.

Statistical analyses

The non-parametric paired Wilcoxon test was used to assess the impact of filtration using the null hypothesis that the median difference following filtration is zero44. Relationships between change in fluorescence following filtration and various independent variables (total bacterial cells, TTCs, SEC, and turbidity) were assessed using the non-parametric Spearman’s Rank test45. Non-parametric techniques were used because of the non-Gaussian distribution of the datasets. All analyses were undertaken in R version 3.4.0 using core commands wilcox.test and cor.test46. Boxplots display the median, the interquartile range, whiskers denote that 10th and 90th percentiles, and dots the 5th and 95th percentiles; these were produced in SigmaPlot version 13.0.

Results

Variation in TLF and HLF in the study areas

The intensity of TLF/HLF in groundwater relates to the degree of urbanisation at the land surface (Fig. 2a). Median TLF reduces from 17.4 QSU in the large city of Dakar, to 7.0 QSU in the medium-sized city of Kisumu, and 1.1–1.2 QSU in the small town of Lukaya and rural Lilongwe & Balaka Districts. Furthermore, median HLF in Dakar is almost 90-fold that of Lukaya.

Neither variations in water temperature nor turbidity are considered to appreciably impact the fluorescence results (Fig. 2b–d). Water temperature across all data vary between 23.2 and 29.6 °C and within individual study areas by 2.5–6.0 °C. Therefore, uncertainty relating to temperature is likely to be limited to a maximum of < 6 and < 9% for TLF and HLF, respectively47,48,49. Any optical attenuation relating to suspended solids is also likely to have limited influence on TLF/HLF with a median turbidity of 0.3–4.6 NTU and 97% all of data < 46.2 NTU50,51.

TLF/HLF are predominantly extracellular in groundwater

There is a significant change in median TLF following filtration (ΔTLF) across the whole dataset (paired Wilcoxon, p < 0.001). Median ΔTLF is a decline of 0.2 QSU (3.1%), which is within the error of repeatability (Fig. 3). The majority (68.6%) of the supplies show no change when considering repeatability uncertainty, with 28.6% declining, and 2.9% increasing. The lower and upper quartiles highlight limited changes of only − 12.2 and 2.6%, respectively.

Within the individual country datasets, significant changes following filtration were observed in Dakar and Kisumu, but not Lukaya nor Lilongwe & Balaka Districts (Fig. 4). The lack of a significant change in Lukaya and Lilongwe & Balaka Districts could be a result of the low unfiltered TLF intensities (median 1.1–1.2 QSU). Consequently, any changes following filtration could be harder to detect amongst repeatability uncertainty (± 0.5 QSU). Overall median changes following filtration in Dakar, Kisumu, Lukaya and Lilongwe & Balaka Districts were − 0.4 (− 2.8%), − 0.3 (− 4.2%), − 0.1 (− 6.2%), 0 (0%) QSU, respectively. The greatest loss in TLF following filtration across the entire dataset was at a spring in Lukaya 28.6 QSU (78.6%), with a further spring in the town experiencing a loss of 2.7 QSU (69%). These springs were gentle seepages, and could be considered more representative of slow-moving surface waters; algae were also visible in the channel where samples were obtained. Given any changes following filtration are insignificant or minimal within country datasets collected in both the dry and the wet seasons, TLF is likely to be predominantly extracellular perenially.

There was no significant change in HLF following filtration (Fig. 5) across the entire dataset (paired Wilcoxon, p 0.861), or within both the Dakar (paired Wilcoxon, p 0.522) and Lukaya (paired Wilcoxon, p 0.704) datasets individually (Figure S1). Although TLF and HLF are correlated in Dakar (ρs 0.678, p < 0.001), contrasting filtration effects suggest that fluorescence is, in part, emanating from two different sources.

Relationships between TLF change following filtration, total bacterial cells, TTCs, SEC, and turbidity

There is a moderate positive correlation between ΔTLF after filtering and total bacterial cells in Dakar (Fig. 6). Note, though, that there is a significant tendency for ΔTLF to decrease with increasing TLF intensity (Figure S2). No other significant correlations exist between ΔTLF and other variables in any country, including turbidity (Fig. 6). It is unsurprising there is no significant correlations in Lukaya and Lilongwe & Balaka Districts, where no significant ΔTLF was observed, but coefficients are included for completeness.

Discussion

Implications for TLF/HLF as faecal indicators

TLF and HLF are predominantly extracellular in groundwater, which supports findings from our earlier TLF pilot study in rural India20. Extracellular TLF/HLF will have different transport properties to larger faecal indicator bacteria and enteric pathogens, such as bacteria, Cryptosporidium oocysts, and Giardia that are around 1, 5, and 10 µm, respectively52. These organisms will be more readily strained between a faecal source and a groundwater source through both the unsaturated and saturated zones. This behaviour could potentially result in false-positives when organisms are removed completely, whilst an elevated TLF/HLF signal remains. Indeed, false-positives have been highlighted as an issue when defining TLF thresholds to indicate the presence of TTCs22. False-positives will be more likely in aquifers exhibiting matrix flow34 where faecal indicator bacteria and pathogens are typically restricted to only metres or tens of metres from sources such as pit latrines53. Co-transport of TLF/HLF and both TTCs and pathogens is more likely in fractured aquifers where rapid transport of bacteria can occur over several kilometres within a few days, for example Heinz et al.54, or alternatively, irrespective of the aquifer, where a source’s integrity is compromised at or near the surface. Co-occurrence of TLF/HLF and TTCs is also more probable where there is a very shallow water table (< 1 m).

Elevated TLF/HLF in the absence of TTCs may still indicate a groundwater source is at-risk. Viruses are the smallest pathogens (27–75 nm) and are often also found in the absence of faecal indicator bacteria and larger pathogens because they can be more mobile in the subsurface55,56. Future work could explore TLF as an indicator of virus contamination where faecal indicator bacteria are ineffective. Sorensen et al.18 also demonstrated through seasonal sampling that TLF tended to remain perennially elevated in some sources whilst TTCs were more transient. Finally, elevated TLF/HLF is likely to mean a source is better connected to the near surface and potential sources of contamination, even if the fluorescent OM may currently relate to non-faecal sources such as plant litter and soil organic matter.

Our results demonstrate a significant correlation between ΔTLF and total bacterial cells in Dakar, and not between ΔTLF and TTCs. These observations may suggest a proportion of tryptophan-like fluorophores are bound within larger protein molecules within cells, although the relationship could be coincidental and a result of other particulate OM being filtered out. Furthermore, it is supportive of TLF being associated with total microbial biomass34 and activity, as opposed to purely TTCs, such as E. coli. Previous work has shown a vast assortment of microbes exhibit TLF57,58,59, including ubiquitous species in the environment23,60,61.

Implications for fluorescence sampling

The extracellular nature of TLF/HLF means there are minimal concerns over comparing groundwater fluorescence data collected from in-situ field sensors and samples that have been filtered prior to laboratory analysis. The filtration of laboratory samples is undertaken in many studies to remove suspended solids and sterilise the water to minimise biologically driven OM transformation prior to analysis.

There is no evidence for turbidity attenuating TLF/HLF in groundwater (Fig. 6). Samples with the highest turbidity in each country (46–153 NTU) also showed no evidence of appreciable change in TLF following filtration (1, 2, − 3, 5%, respectively). This result further supports Khamis et al.50 in suggesting turbidity is unlikely to have any impact on the in-situ fluorescence monitoring of groundwater. With no observed relationship between ΔTLF and turbidity, and no significant ΔHLF, it is unconfirmed why some ΔTLF/ΔHLF are positive beyond any repeatability error. Many of these positive data are at greater fluorescent intensity, than the repeatability study conducted herein, with previous evidence that error increases with greater intensity; hence, these positives values may not indicate an appreciable change. However, it is also possible some of these data are indicative of either anomalously low unfiltered or high filtered fluorescence values. Anomalous low readings could occur due to air bubbles trapped within the sensor and high readings due to contamination resulting from sensor handling22.

Conclusions

Tryptophan-like fluorophores are predominantly extracellular in groundwater. Significant changes in TLF following filtration were only observed beneath the cities of Kisumu, Kenya, and Dakar, Senegal, where TLF was elevated in comparison to the small town of Lukaya, Uganda and rural Lilongwe & Balaka Districts, Malawi. Nevertheless, TLF was still 93.2–97.2% extracellular on average. In Dakar, tryptophan-like fluorophores associated with the unfiltered > 0.22 µm fraction were moderately correlated with total bacterial cells. Humic-like fluorophores are extracellular in groundwater.

The extracellular nature of TLF/HLF means they will have different transport properties in comparison to faecal indicator bacteria and larger pathogens, which will be more readily strained in both the unsaturated and saturated zones of the subsurface. Co-transport is least likely in intergranular aquifers where the water table exceeds a metre depth below ground level resulting in a higher likelihood of false-positives. TLF/HLF should be considered more precautionary indicators of microbial risks than faecal indicator bacteria in groundwater-derived drinking water.

References

Bieroza, M., Baker, A. & Bridgeman, J. Relating freshwater organic matter fluorescence to organic carbon removal efficiency in drinking water treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 1765–1774 (2009).

Birdwell, J. E. & Engel, A. S. Characterization of dissolved organic matter in cave and spring waters using UV–Vis absorbance and fluorescence spectroscopy. Org. Geochem. 41, 270–280 (2010).

Carstea, E. M., Baker, A., Bieroza, M. & Reynolds, D. Continuous fluorescence excitation–emission matrix monitoring of river organic matter. Water Res. 44, 5356–5366 (2010).

Chen, M., Price, R. M., Yamashita, Y. & Jaffé, R. Comparative study of dissolved organic matter from groundwater and surface water in the Florida coastal Everglades using multi-dimensional spectrofluorometry combined with multivariate statistics. Appl. Geochem. 25, 872–880 (2010).

Fellman, J. B., Hood, E. & Spencer, R. G. Fluorescence spectroscopy opens new windows into dissolved organic matter dynamics in freshwater ecosystems: a review. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 2452–2462 (2010).

Huang, S.-B. et al. Linking groundwater dissolved organic matter to sedimentary organic matter from a fluvio-lacustrine aquifer at Jianghan Plain, China by EEM-PARAFAC and hydrochemical analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 529, 131–139 (2015).

Hudson, N., Baker, A. & Reynolds, D. Fluorescence analysis of dissolved organic matter in natural, waste and polluted waters—a review. River Res. Appl. 23, 631–649 (2007).

Baker, A. Fluorescence excitation-emission matrix characterization of some sewage-impacted rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 948–953 (2001).

Baker, A. & Inverarity, R. Protein-like fluorescence intensity as a possible tool for determining river water quality. Hydrol. Process. 18, 2927–2945 (2004).

Carstea, E. M., Bridgeman, J., Baker, A. & Reynolds, D. M. Fluorescence spectroscopy for wastewater monitoring: a review. Water Res. 95, 205–219 (2016).

Goldman, J. H., Rounds, S. A. & Needoba, J. A. Applications of fluorescence spectroscopy for predicting percent wastewater in an urban stream. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4374–4381 (2012).

Lapworth, D. J., Gooddy, D., Butcher, A. & Morris, B. Tracing groundwater flow and sources of organic carbon in sandstone aquifers using fluorescence properties of dissolved organic matter (DOM). Appl. Geochem. 23, 3384–3390 (2008).

Reynolds, D. & Ahmad, S. Rapid and direct determination of wastewater BOD values using a fluorescence technique. Water Res. 31, 2012–2018 (1997).

Zhou, Y. et al. Dissolved organic matter fluorescence at wavelength 275/342 nm as a key indicator for detection of point-source contamination in a large Chinese drinking water lake. Chemosphere 144, 503–509 (2016).

Stedmon, C. A. et al. A potential approach for monitoring drinking water quality from groundwater systems using organic matter fluorescence as an early warning for contamination events. Water Res. 45, 6030–6038 (2011).

Frank, S., Goeppert, N. & Goldscheider, N. Fluorescence-based multi-parameter approach to characterize dynamics of organic carbon, faecal bacteria and particles at alpine karst springs. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 1446–1459 (2017).

Nowicki, S., Lapworth, D. J., Ward, J. S., Thomson, P. & Charles, K. Tryptophan-like fluorescence as a measure of microbial contamination risk in groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 646, 782–791 (2019).

Sorensen, J. et al. In-situ tryptophan-like fluorescence: a real-time indicator of faecal contamination in drinking water supplies. Water Res. 81, 38–46 (2015).

Sorensen, J. et al. Tracing enteric pathogen contamination in sub-Saharan African groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 538, 888–895 (2015).

Sorensen, J. et al. Are sanitation interventions a threat to drinking water supplies in rural India? An application of tryptophan-like fluorescence. Water Res. 88, 923–932 (2016).

Sorensen, J. et al. Online fluorescence spectroscopy for the real-time evaluation of the microbial quality of drinking water. Water Res. 137, 301–309 (2018).

Sorensen, J. P. et al. Real-time detection of faecally contaminated drinking water with tryptophan-like fluorescence: defining threshold values. Sci. Total Environ. 622, 1250–1257 (2018).

Fox, B., Thorn, R., Anesio, A. & Reynolds, D. The in situ bacterial production of fluorescent organic matter; an investigation at a species level. Water Res. 120, 350–359 (2017).

Ikeda, M. Towards bacterial strains overproducing L-tryptophan and other aromatics by metabolic engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69, 615 (2006).

Cumberland, S., Bridgeman, J., Baker, A., Sterling, M. & Ward, D. Fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool for determining microbial quality in potable water applications. Environ. Technol. 33, 687–693 (2012).

Baker, A., Elliott, S. & Lead, J. R. Effects of filtration and pH perturbation on freshwater organic matter fluorescence. Chemosphere 67, 2035–2043 (2007).

Bieroza, M. Z. & Heathwaite, A. L. Unravelling organic matter and nutrient biogeochemistry in groundwater-fed rivers under baseflow conditions: uncertainty in in situ high-frequency analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 1520–1533 (2016).

Griebler, C. & Lueders, T. Microbial biodiversity in groundwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 54, 649–677 (2009).

Marmonier, P., Fontvieille, D., Gibert, J. & Vanek, V. Distribution of dissolved organic carbon and bacteria at the interface between the Rhône River and its alluvial aquifer. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 14, 382–392 (1995).

Pedersen, K. Exploration of deep intraterrestrial microbial life: current perspectives. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185, 9–16 (2000).

van Driezum, I. H. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of bacterial biomass and activity to understand surface and groundwater interactions in a highly dynamic riverbank filtration system. Sci. Total Environ. 627, 450–461 (2018).

Faye, S. C. et al. Tracing natural groundwater recharge to the Thiaroye aquifer of Dakar Senegal. Hydrogeol. J. 27, 1067–1080 (2019).

Faye, S. C., Faye, S., Wohnlich, S. & Gaye, C. B. An assessment of the risk associated with urban development in the Thiaroye area (Senegal). Environ. Geol. 45, 312–322 (2004).

Sorensen, J. P. et al. In-situ fluorescence spectroscopy indicates total bacterial abundance and dissolved organic carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 139419 (2020).

Consultants, D. Rural domestic water resources assessment Kisumu District. Available at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/824-5816.pdf. (1988).

Okotto-Okotto, J., Okotto, L., Price, H., Pedley, S. & Wright, J. A longitudinal study of long-term change in contamination hazards and shallow well quality in two neighbourhoods of Kisumu, Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 4275–4291 (2015).

Olago, D. O. Constraints and solutions for groundwater development, supply and governance in urban areas in Kenya. Hydrogeol. J. 27, 1031–1050 (2019).

Chavula, G. M. S. in Groundwater availability and use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of 15 countries (eds Paul Pavelic et al.) (International Water Management Institute (IWMI), 2012).

Cole, B., Pinfold, J., Ho, G. & Anda, M. Exploring the methodology of participatory design to create appropriate sanitation technologies in rural Malawi. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 4, 51–61 (2013).

Diédhiou, M. et al. Tracing groundwater nitrate sources in the Dakar suburban area: an isotopic multi-tracer approach. Hydrol. Process. 26, 760–770 (2012).

Nayebare, J. et al. WASH conditions in a small town in Uganda: how safe are on-site facilities?. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2019.070 (2019).

Wright, J. A. et al. A spatial analysis of pit latrine density and groundwater source contamination. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 4261–4272 (2013).

Marie, D., Rigaut-Jalabert, F. & Vaulot, D. An improved protocol for flow cytometry analysis of phytoplankton cultures and natural samples. Cytom. Part A 85, 962–968 (2014).

Hollander, M. & Wolfe, D. A. Nonparametric Statistical Methods (Wiley, New York, 1973).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 15, 72–101 (1904).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org. (2017).

Baker, A. Thermal fluorescence quenching properties of dissolved organic matter. Water Res. 39, 4405–4412 (2005).

Downing, B. D., Pellerin, B. A., Bergamaschi, B. A., Saraceno, J. F. & Kraus, T. E. Seeing the light: the effects of particles, dissolved materials, and temperature on in situ measurements of DOM fluorescence in rivers and streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 10, 767–775 (2012).

Watras, C. et al. A temperature compensation method for CDOM fluorescence sensors in freshwater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 9, 296–301 (2011).

Khamis, K. et al. In situ tryptophan-like fluorometers: assessing turbidity and temperature effects for freshwater applications. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 17, 740–752 (2015).

Saraceno, J. F., Shanley, J. B., Downing, B. D. & Pellerin, B. A. Clearing the waters: Evaluating the need for site-specific field fluorescence corrections based on turbidity measurements. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 15, 408–416 (2017).

Hunt, R. J. & Johnson, W. P. Pathogen transport in groundwater systems: contrasts with traditional solute transport. Hydrogeol. J. 25, 921–930 (2017).

Graham, J. P. & Polizzotto, M. L. Pit latrines and their impacts on groundwater quality: a systematic review. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 521–530 (2013).

Heinz, B. et al. Water quality deterioration at a karst spring (Gallusquelle, Germany) due to combined sewer overflow: evidence of bacterial and micro-pollutant contamination. Environ. Geol. 57, 797–808 (2009).

Borchardt, M. A., Haas, N. L. & Hunt, R. J. Vulnerability of drinking-water wells in La Crosse, Wisconsin, to enteric-virus contamination from surface water contributions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5937–5946 (2004).

Wu, J., Long, S., Das, D. & Dorner, S. Are microbial indicators and pathogens correlated? A statistical analysis of 40 years of research. J. Water Health 9, 265–278 (2011).

Bridgeman, J., Baker, A., Brown, D. & Boxall, J. Portable LED fluorescence instrumentation for the rapid assessment of potable water quality. Sci. Total Environ. 524, 338–346 (2015).

Dartnell, L. R., Roberts, T. A., Moore, G., Ward, J. M. & Muller, J.-P. Fluorescence characterization of clinically-important bacteria. PLoS ONE 8, e75270 (2013).

Determann, S., Lobbes, J. M., Reuter, R. & Rullkötter, J. Ultraviolet fluorescence excitation and emission spectroscopy of marine algae and bacteria. Mar. Chem. 62, 137–156 (1998).

Elliott, S., Lead, J. & Baker, A. Characterisation of the fluorescence from freshwater, planktonic bacteria. Water Res. 40, 2075–2083 (2006).

Nakar, A. et al. Quantification of bacteria in water using PLS analysis of emission spectra of fluorescence and excitation–emission matrices. Water Res. 169, 115197 (2019).

Acknowledgements

BGS authors publish with the permission of the Executive Director, British Geological Survey (UKRI). Any identification of equipment does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the authors and their respective employers. JPRS, AFC, JN, DMLD, AP, RR, JK, LM, SCF, CBG, RK, DO, MO, RGT acknowledge support from the Royal Society/UK Department for International Development (DFID) Africa Capacity Building Initiative AfriWatSan Project [AQ140023] for fieldwork in Kenya, Senegal and Uganda, and co-author contributions. JPRS, JO, DJL acknowledge support from the DFID/Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Future Climate for Africa (FCFA) HyCRISTAL Project [NE/M020452/1] for co-supported fieldwork in Kenya. GG, JSTW, MM, DJL, AMM acknowledge support from the DFID/NERC/Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) UPGro Hidden Crisis Project [NE/L002078/1] and the UKaid funded REACH trigr Project [GA/16F/057] for fieldwork in Malawi. JSTW acknowledges support from SCENARIO NERC Doctoral Training Partnership Grant Number NE/L002566/1. JPRS was supported by the British Geological Survey NC-ODA Grant NE/R000069/1: Geoscience for Sustainable Futures for data analysis and writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.R.S. wrote the manuscript and prepared all the figures. J.P.R.S., S.C.F., C.B.G., R.K., D.J.L., A.M.M., M.M., D.O., M.O., L.C., R.G.T. co-designed the study. J.P.R.S., A.F.C., J.N., D.M.L.D., A.P., R.R., G.G., J.S.T.W., J.K., J.O.O., L.M. acquired the field data. T.G. and D.S.R. undertook laboratory analysis. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sorensen, J.P.R., Carr, A.F., Nayebare, J. et al. Tryptophan-like and humic-like fluorophores are extracellular in groundwater: implications as real-time faecal indicators. Sci Rep 10, 15379 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72258-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72258-2

This article is cited by

-

Field evidences of fluorescent dissolved organic matter (FDOM) as potential fingerprints for agricultural and urban sources in river environment

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Application of the D-A-(C) index as a simple tool for microbial-ecological characterization and assessment of groundwater ecosystems—a case study of the Mur River Valley, Austria

Österreichische Wasser- und Abfallwirtschaft (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.