Abstract

Some nonlinear radiations such as superfluorescence can be understood as cooperative effects between atoms. We regard cooperative radiations as a manifested effect secondary to the intrinsic synchronization among the two-level atoms and propose the entanglement measure, concurrence, as a time-resolved measure of synchronization. Modeled on two cavity-coupled qubits, the evolved concurrence monotonically increases to a saturated level. The finite duration required for the rising to saturation coincides with the time delay characteristic to the initiation of superfluorescence, showing the role of synchronization in establishing the cooperation among the qubits. We verify concurrence to be a good measure of synchronization by comparing it with asynchronicity computed from the difference between the density matrices of the qubits. We find that the feature of time delay agrees in both measures and is determined by the coupling regimes of the cavity-qubit interaction. Specifically, synchronization is impossible in the weak coupling regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Centuries ago, Huygens studied the correlation among the motions of pendulums and discovered the synchronization pattern of these individual oscillators under the influence of a common oscillator they are coupled to1. How synchronizations arise in different situations has since remained a problem of interest2. In recent years, the study of the classical phenomenon has been revived under the quantum regime. Synchronization is observed between a pair of nanomechanical oscillators3 and on the motions of the Cooper pairs among Josephson-insulated superconducting islands4. It is also ubiquitously predicted between a qubit and an oscillator5, between a cavity field and an oscillator6, between two oscillators7, among a trapped group of cold atoms8, and even between a quantum Van der Pol oscillator and an external drive9.

Here we study the synchronization of two qubits coupled indirectly to each other through a cavity field, in specific relevance to the quantum optical phenomenon of superfluorescence10,11. This nonlinear fluorescent effect embodies Dicke’s formulation of superradiance12, where the nonlinearity exemplifies in the \(N^{2}\)-dependence of the emitted radiation intensity from an ensemble of N atoms. Furthermore, the emitted photonic pulse peaks after a positive time delay13,14 that bears no direct dependence on the atom-field coupling strength, showing the collective interatomic motion to be a nonlinear process. Experimentally recorded on hydrofluoric gas15, cesium16, and most recently rubidium vapor17, this delay shows the necessity of a finite time during which the atoms establish cooperation before the radiation is initiated18.

Such a delay is also characteristic of synchronization: it takes finite time for the classical Huygens pendulums to reach in-phase oscillations. If one regards the correlated atoms as quantized Huygens oscillators concentrated on the lowest two levels at the weak-energy limit, it is not hard to find the resemblance between cooperated radiation and synchronization. In this paper, we formalize the study of this resemblance by analyzing the entanglement dynamics19,20,21 of two cavity-coupled qubits, which is the minimum-dimensional system that emulates the structure of an atomic ensemble undergoing cooperated radiation.

Many different metrics have been proposed over the years to measure synchronization of different quantum systems, such as a set of two-level systems in a shared bath22, quantum dots23, and resonator modes24. We note that synchronization as a quantum correlation can be studied using quantum discord25, as it was for two oscillators26, and non-locality. The advantage of entanglement approach is avoiding the unnecessary constraint to two-party correlation. We use specifically, in contrast to quantum discord, concurrence27 as the entanglement measure to quantify quantum synchronization in order to extract the temporal features of atomic cooperation. Concurrence is broadly applicable, especially for multipartite system. After it was introduced for two-qubit systems27, it was soon extended to the cases of three qubits28 and N-qubits29. Concurrence has then been generalized to two multi-level systems30,31 and finally to multipartite multi-level systems32. Given its generality, concurrence permits synchronization to be exemplified not only between two qubits, but among three parties that include the cavity field. In addition, synchronization is present in a Hilbert space of finite dimensions33, so non-locality is not an essential factor to initiate synchronization.

Further, concurrence is proved to be a good measure for static analysis of collective phenomena such as radiation34,35. Therefore, we extend the employment of multipartite concurrence to the dynamical analysis of the finite-dimensional cavity-qubit system. It is found that the entanglement among the components universally begins at a zero level and rises to a saturated value after a finite delay. The length of the delay and the saturated level depend nonlinearly on the cavity-qubit coupling strength. We use numerical simulations to show that the nonlinear dependence is divisible into weak, strong, and ultrastrong coupling regimes, verifying the role of operation regimes36 in the dynamics of superconducting circuits. Under all coupling strengths, the saturated entangled state is sustained thereafter, where oscillations in concurrence only exists locally about the saturation offset with an amplitude much smaller than the offset. These distinctive features of a synchronized state stand in constrast to the sudden death or death and revival37 one usually sees in entanglement evolution.

To verify the coincidence between the maximization of concurrence and the dynamic process of synchronization, we introduce a synchronization measure computed from the density matrix, which is modified from the synchronization measure introduced on the (x, p)-quadratures of quantum oscillators24. The transition point in time produced from the synchronization measures matches exactly the delay time found in the concurrence evolution, proving that the qubit-to-qubit synchronization is well registered in the entanglement. Moreover, since two-qubit systems on a superconducting circuit can produce superfluorescent pulses38, the synchronization delay is associated with the initiation of superradiance, thereby establishing the dynamic correlation between entanglement and the atomic cooperation for collective phenomena.

Results

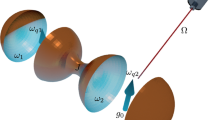

The tripartite system

The derivation for the dynamics discussed above is modeled on a generic cavity quantum electrodynamic (QED) system where each qubit is coupled to the cavity through dipole-field interaction under the rotating wave approximation. The parameters adopted for the numerical analysis are sourced from the superconducting circuit implementation39,40 of the cavity QED system. Hence, the tripartite system can be illustrated from the model Fig. 1, where the cavity is indicated by the stripped waveguide and the qubits are located at the anti-nodes of the cavity field to ensure maximum coupling.

The total system Hamiltonian \(H=H_{0}+H_{\mathrm{int}}+H_{\mathrm {ext}}\) is composed of three parts: the free Hamiltonian, the interactions among the system components, and the external driving, which reads, respectively, \((\hbar =1)\)

In \(H_{0}\), \(\omega _{c}\) denotes the frequency of the cavity mode and \(\Omega _{A}\) (\(\Omega _{B}\)) denotes the transition frequency of the left (right) qubit, associated with the Pauli matrix \(\sigma _{A,z}\) (\(\sigma _{B,z}\)). In \(H_{\mathrm {int}}\), \(\eta _{A}(\eta _{B})\) denotes the coupling strength to the left (right) qubit. In \(H_{\mathrm {ext}}\), the external driving field has frequency \(\omega _{D}\) and driving strength \(\varepsilon _{D}\).

The combined system of a cavity and two qubits has its bare states described by the tensor product state \(\{|e_{A}\rangle ,|g_{A}\rangle \}\otimes \{|n\rangle \}\otimes \{|e_{B}\rangle ,|g_{B}\rangle \}\), where \(|e_{A}\rangle \) (\(|g_{A}\rangle \)) denotes the excited (ground) state of the left qubit; \(|n\rangle \) denotes the Fock number states of the cavity mode; \(|e_{B}\rangle \) (\(|g_{B}\rangle \)) denotes the excited (ground) state of the right qubit. To simplifying the notation, we omit the subscripts A and B when writing the product states and let the first letter denote the state of the left qubit, the middle letter that of the cavity mode, and the last letter that of the right qubit (e.g. \(|e,n,g\rangle =|e_{A}\rangle \otimes |n\rangle \otimes |g_{B}\rangle \)).

The free Hamiltonian \(H_{0}\) and the interaction Hamiltonian \(H_{\mathrm{int}}\) constitute a closed subsystem, for which there exist dressed states that diagonalize \(H_{0}+H_{\mathrm {int}}\). To find an analytical expression for the dressed states, we consider the sets of energy-conserving states \(|e,n,g\rangle \), \(|g,n+1,g\rangle \), and \(|g,n,e\rangle \), which are resonant within single-photon processes, to contribute to a dressed state for each n. In other words, the state \(|e,n,e\rangle \) which is resonant with \(|g,n+2,g\rangle \) through a double-photon process is omitted, allowing the derivation below to be purely analytical. Single-photon processes among the collective states of an ensemble of two-level systems are responsible for the majority of qubit operations useful for quantum information processing, which includes generating the entangled W-state34 and the multistable attractor states41. Such collective states are also experimentally proven on superconducting qubits42.

These single-photon resonant states form an invariant subspace, for which the closed Hamiltonian consists of \(3\times 3\) symmetric block matrices. Therefore, we have the eigen-equation

where the eigenvectors \(|u_{k}^{(n)}\rangle \) denote the dressed states that diagonalize the \(3n\times 3n\) matrix \(H_{0}+H_{\mathrm {int}}\) and the eigenvalues \(E_{k}^{(n)}\) denote the dressed-state energies in the diagonalized space. The index k enumerates \(\{1,2,3\}\) to indicate the dressed levels within the n-th cluster.

Block-diagonalizing \(H_{0}+H_{\mathrm {int}}\) for Eq. (4) results in a cubic equation of \(E_{k}^{(n)}\) for each n, whose roots are

In the equation, \(\Delta =\Omega _{A}-\Omega _{B}\) denotes the detuning between the two qubits and \(\delta =\omega _{c}-\Omega _{A}-\Omega _{B}\) the detuning between the cavity and the two qubits combined. The angle \(\theta \) is defined through its triple-angle formula

The corresponding eigenvector reads

where the transformation coefficients are

with \(Z_{k}^{(n)}\) being the normalization constant

The detailed derivation is given in the Methods section.

In the dressed space spanned by the basis vectors of Eq. (7), the closed Hamiltonian is written in the diagonalized form

while the annihilation operator

under the single-photon processes is transformed to

where the indices j and k enumerate over the set \(\{1,2,3\}\).

The permitted dressed level transitions induced by the external driving can be found by substituting Eq. (14) into Eq. (3). In the following, we consider the weak-energy limit where the transitions are confined to the lowest two clusters of states (\(n=0\) and \(n=1\)). This consideration greatly simplify the numerical analysis of the evolution by confining the matrix representation of the equations of motion to 6 dimensions. It is also realistic since higher clusters require the much less likely occurrence of multi-photon resonance driven by the external \(\varepsilon _{D}\). Though obtaining states of high photon number are possible with the assistance of auxiliary qubits43, they are much shorter-lived. We therefore write the total Hamiltonian as

in the dressed space. Introducing the time-dependent state vector

in the confined state space and applying it to the Hamiltonian above, one has the Schrödinger equations of the time coefficients

where \(\lambda _{l}\) denotes the weight of the summation over the index l for the system component A (the left qubit), B (the right qubit), or C (the cavity), i.e. \(\lambda _{A}=\lambda _{B}=1\) and \(\lambda _{C}=\sqrt{2}\). In the equations, we observe the Einstein summation convention.

In the rotating frame \(c_{j}\left( t\right) =c_{j}^{\prime }\left( t\right) \mathrm {exp}\{-iE_{j}^{(0)}t\}\) and \(d_{j}(t)=d_{j}^{\prime }(t)\mathrm {exp}\{-iE_{j}^{(1)}t\}\), the coupled equations can be written as the linear homogeneous system of differential equations \(\dot{{\mathbf {c}}^{\prime }}=A{\mathbf {c}}^{\prime }\) where \(\mathbf {c^{\prime }}=\left[ c_{1}^{\prime }\;c_{2}^{\prime } \;c_{3}^{\prime }\;d_{1}^{\prime }\;d_{2}^{\prime }\;d_{3}^{\prime }\right] \) and

where the square brackets \([\cdot ]\) indicate \(3\times 3\) submatrices in the matrix A with j and k being the row and the column indices, respectively. We denote \(\zeta _{kj}=\omega _{D}-\left( E_{k}^{\left( 1\right) }-E_{j}^{\left( 0\right) }\right) \) for the detuning between the driving and the dressed states. Since A is integrable, then solving the linear system for \(\{c_{j},d_{j}\}\) and expanding the dressed states by using the bare states in Eq. (16), one can find the expansion coefficients \(\gamma \) of the state vector

back in the bare state space.

Evolution of the state vector

To see that the evolution of the state vector can initiate the synchronization of the two delocalized qubits, we assume the cavity mode is initially driven by the external field to reach a partial population inversion while setting the qubits initially at the ground. In other words, the expansion coefficients at the initial moment are: \(\gamma _{C}^{\left( 0\right) }=\sqrt{0.9}\), \(\gamma _{C}^{\left( 1\right) }=\sqrt{0.1}\), and \(\gamma _{A}^{\left( 0\right) }=\gamma _{B}^{\left( 0\right) }=\gamma _{A}^{\left( 1\right) }=\gamma _{B}^{\left( 1\right) }=0\).

We plot out the evolutions of these coefficients in Fig. 2, using the experimentally accessible parameters of superconducting charge-phase qubits40: \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =\Omega _{B}/2\pi =6.1\) GHz, \(\eta _{A}/2\pi =\eta _{B}/2\pi =500\) MHz, and \(\omega _{c}/2\pi =6.32\) GHz. The frequency of the external field is maintained at \(\omega _{D}/2\pi =5.3\) GHz. The lower set of states with \(n=0\) is given in Fig. 2a whereas the upper set with \(n=1\) is given in Fig. 2b. Note that, for the implementation of cavity QED system on a superconducting circuit, the cavity field refers to the standing microwave field that is sustained in the stripline (Cf. Fig. 1) and coupled capacitively to the Josephson-junction qubit. Hence, by distancing qubits and placing them at different positions relative to the cavity nodes, it is possible to realize arbitrary cavity-qubit interactions. For instance, maximal coupling can be obtained by placing the qubits at antinodes42.

We observe that for both the lower set and the upper set of states, there exists a transition point of the oscillations of the coefficients, which is located at about \(3.7\mu \mathrm {s}\) in the plots. In particular, \(\gamma _{C}^{\left( 0\right) }\) is transited from a region of shrinking oscillation to a region of small fluctuation at this point. Meanwhile, \(\gamma _{A}^{\left( 1\right) }\),\(\gamma _{B}^{\left( 1\right) }\), and \(\gamma _{C}^{\left( 1\right) }\) are transited from an amplifying region to a region of saturated oscillation envelope. The contrasting behavior of the two sets of coefficients demonstrates that the energy excitation that exists in the cavity mode is transferred to the left and the right qubits whose complementary oscillations imply the build-up of the entanglement between them.

Bipartite and tripartite concurrences

To fully capture the evolution characteristics of the two cavity-coupled qubits from a holistic point of view, we apply two entanglement measures—bipartite concurrence and tripartite concurrence—to the state vector of the total system.

The bipartite concurrence quantifies the inseparability of the joint pure state of two coupled systems of arbitrary dimensions by inverting the density matrix. For our case here, the joint state is the product state \(|\psi _{AB}\rangle \) of the indirectly coupled left and right qubits. Thus the inversion is conducted through the superoperator \(S_{D_{1}}\otimes S_{D_{2}}\) where the dimensions \(D_{1}=D_{2}=2\) and the bipartite concurrence is defined as \(C_{2}(\psi _{AB})=\sqrt{\langle \psi _{AB}|S_{2}\otimes S_{2}\left( |\psi _{AB}\rangle \langle \psi _{AB}|\right) |\psi _{AB}\rangle }\). Given the consideration of pure states, for which \(\mathrm {tr}\rho ^{2}=1\) and \(\mathrm {tr}\rho _{A}^{2}=\mathrm {tr}\rho _{B}^{2}\), the definition reduces to \(C_{2}(\psi _{AB})=\sqrt{2\left[ 1-\mathrm {tr}\left( \rho _{A}^{2}\right) \right] }\) where \(\rho _{A}=\mathrm {tr}_{B}\left( \mathrm {tr}_{C}\left( |\psi \rangle \langle \psi |\right) \right) \) is the reduced density matrix of the left qubit.

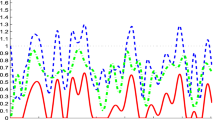

Applying \(|\psi \left( t\right) \rangle \) in Eq. (20) to the formula, we derive the evolution of the bipartite concurrence, shown as the blue curve in Fig. 3. It becomes apparent that the transition point that manifests in Fig. 2a,b signifies the concurrence reaching a maximum after a gradual monotonic increase in the oscillation envelope. This maximum concurrence is retained thereafter. The finite delay time \(\tau _{D}=3.7\mu \mathrm {s}\) that the concurrence spends to reach its maximal value reflects the time the two qubits use to reach a maximal synchronization through their mutual couplings to the cavity mode.

Time evolution of the bipartite concurrence \(C_{2}\left( \psi _{AB}\right) \) between the two qubits (blue) and the tripartite concurrence \(C_{3}\left( \psi \right) \) among the qubits and the cavity (red). A symmetric scenario is assumed between the left and the right qubits: \(\eta _{A}/2\pi =\eta _{B}/2\pi =500\) MHz and \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =\Omega _{B}/2\pi =6.1\) GHz.

The cavity mode plays an active part in initiating the entanglement between the two qubits. From the entanglement-theoretic point of view, the concurrence is distributed among the qubits as well as the cavity. Taking away the pairwise entanglements between any two parties in the tripartite system, one obtains the residual concurrence that remains as an equally distributed entanglement among all three parties28. Extending the original formulation on three-qubit systems, we generalize the inversion operations for two arbitrary-dimensional systems given above to three arbitrary-dimensional system. That is, we introduce the superoperator

for our \(D_{1}\times D_{2}\times D_{3}\) dimension tripartite system, where \(D_{1}=D_{3}=2\) for the qubits and \(D_{2}=n\) for the cavity mode. In Eq. (21), I denotes the identity matrix while \(\rho _{A}\), \(\rho _{C}\), \(\rho _{B}\), \(\rho _{AB}\), \(\rho _{CB}\), and \(\rho _{AC}\) denote the reduced density matrices of the components and the two-component subsystems. Applying the inversion, we thus derive a tripartite residual concurrence

Again, using Eq. (20), we plot the tripartite concurrence as the red curve in Fig. 3. One can verify from the plot that the residual concurrence evolves in a similar fashion, which contains a signifying transition point at the exactly same location \(\tau _{D}\) as that of the bipartite concurrence. Before \(\tau _{D}\), it arises from a zero value under a similarly increasing envelope whereas, after \(\tau _{D}\), it retains a non-zero saturated value. The identical delay time again demonstrates the duration that the system components spend on cooperation before maximal synchronization is reached.

Comparing Figs. 2 and 3, one sees that the energy quantum first dwells on the cavity mode (\(|g,1,g\rangle \) and \(|g,2,g\rangle \)) without being emitted and absorbed by the qubits. Only when the two qubits start to establish a cooperated motion does the qubit-cavity-qubit resonance become effective such that the qubits be excited to their respective excited states \(|e,1,g\rangle \) and \(|g,1,e\rangle \). The entanglement is also established among the three components when the excitation commences.

Comparison of the time evolutions of the tripartite concurrences between the symmetric (red curve) and the asymmetric (green curve) scenarios. For the symmetric case, both qubits are set to \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =\Omega _{B}/2\pi =6.1~\mathrm {GHz}\). For the asymmetric case, the right qubit is adjusted to \(\Omega _{B}/2\pi =7.1\)GHz. Coupling strengths are retained at \(\eta _{A}/2\pi =\eta _{B}/2\pi =500\)MHz throughout.

The concurrences plotted in Fig. 3 are computed upon a symmetric setting of system parameters: the level spacings and the coupling strengths of the qubits are assumed identical. The tripartite concurrence of an asymmetric scenario with the right qubit level spacing raised to \(\Omega _{B}/2\pi =7.1\,\mathrm {GHz}\) is shown as the green curve in Fig. 4 while the rest of the parameters remain unchanged. For comparison, the symmetric case is plotted as the red curve in the background. We observe that the delay to saturated synchronization is inversely correlated with the larger eigenfrequency out of the two qubits. For the case in Fig. 4, increasing \(\Omega _{B}\) reduces delay time \(\tau _{D}\). On the other hand, symmetric settings lead to maximal synchronization at saturation. The asymmetric case given by the green curve has the saturated synchronization reduced to a lower level. Simulation under parameters set to varied values (not shown in figures) verify these observations.

We note that the dynamics originated from the equations of motion (17)–(18) does not take into consideration the relaxation effects which would require a master equation approach under the presence of an environment. Their omission greatly simplifies our derivations and assists the illustration of the temporal features during the synchronization. These features would not be obscured even when environmental effects are observed since their time scales are much shorter than accessible coherence times on superconducting circuits. For instance, the synchronization delays in both settings of Fig. (4) appear within the first 4 µs after initiation. Whereas, superconducting qubits can achieve coherence time up to 100 µs using fabrication techniques44 and even up to hundreds of µs when an error-correcting feedback mechanism is implemented45.

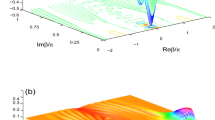

The synchronization between the qubits is also affected by how strong they are driven by the cavity mode, i.e. the coupling strengths \(\eta _{A}\) and \(\eta _{B}\). Shown in Fig. 5 for the symmetric scenario \(\eta _{A}=\eta _{B}\) in a semilog plot, the greater is the coupling, the lesser is the delay \(\tau _{D}\). The numerical fit shows that the delay obeys a quadratic relation over the exponential increase in coupling strength. After the delay, a shorter delay time is associated with a higher saturated level of concurrence, showing a stronger synchronization between the qubits are reflected in both short delay and higher entanglement measure.

The time delay \(\tau _{D}\) is plotted as a function of the dimensionless coupling strength \(\eta /\Omega \) in a semilog scale. Symmetric setting is assumed: the qubit level spacings \(\Omega /2\pi =\Omega _{A,B}/2\pi =6.1\) GHz and the coupling strength \(\eta =\eta _{A,B}\). The circles indicate the data points in the simulation runnings.

Asynchronicity

Multi-partite concurrence as a measure of synchronization reveals a gradual increase between two qubits in the time domain, explaining the existence of a delay in the superfluorescent pulse of cooperated radiation from a system-intrinsic point of view. This synchronization is affected by many factors, among which the symmetry of the system parameters plays an important part. Tuning the system from a symmetric setting to an asymmetric setting is accompanied by tuning the transition rates of the qubits from a synchronous setting to an asynchronous setting. For the latter, we refer to the scenario where the population of the left qubit oscillates at a Rabi frequency not synchronous to that of the right qubit.

However, since two oscillators sharing a common oscillating platform are able to synchronize after certain time duration according to classical mechanics, we expect the qubits sharing the cavity resonator would behave similarly. To precisely describe the transition process from asynchronous regime to synchronous regime, we extend the quantum synchronization measure introduced in Ref.24 for continuous variable systems to discrete systems. We consider instead the measure of asynchronicity

that compares the difference between two density matrices for two two-level systems.

To consider the scenario where the sychronization is initiated from the cavity field as the medium, we let the initial state be only populated in the first and second excited state of the cavity mode, i.e. \(|\psi (0)\rangle =3|g,1,g\rangle /\sqrt{10}+|g,2,g\rangle /\sqrt{10}\). In a superconducting circuit where the cavity mode corresponds to the photonic number state of the stripline resonator, the population is controlled through a resonant microwave pulse, which has a time duration commensurate with the cavity Rabi period, to be fed into the waveguide input46. For example, a \(\pi \)-pulse sends half of the population from \(\left| 0\right\rangle \) to \(\left| 1\right\rangle \). If imaginary phases in the coefficients of the eigenstates are desired, they can be fine-tuned with the assistance of an auxiliary qubit43. \(\left| 2\right\rangle \) is here partially populated to emulate the resonance process where the equally spaced levels of the cavity mode has \(\left| 1\right\rangle \) resonant with \(\left| 2\right\rangle \) simultaneously with \(\left| 0\right\rangle \). Given the initial condition, we find that a symmetric setting \(\Omega _{A}=\Omega _{B}\) would always lead to a zero asynchronicity throughout independent of the coupling strengths \(\eta _{A}\) and \(\eta _{B}\). When \(\Omega _{A}\ne \Omega _{B}\), the asymmetry leads to coupling-dependent asynchronicity, as shown by the plots given in Fig. 6 for five settings of coupling strengths.

Asynchronization \({\mathcal {A}}\) of two cavity-coupled qubits under five different coupling strengths: \(\eta _{A}/2\pi =\eta _{B}/2\pi =200\)MHz (pink), 300MHz (yellow), 400MHz (purple), 500MHz (green), and 600MHz (blue). The qubit level spacings are kept at the asymmetric setting \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =6.1~\mathrm {GHz}\) and \(\Omega _{B}/2\pi =7.1~\mathrm {GHz}\).

No matter the coupling strength, there exists a transition point after which the asynchronicity remains at a stable value. This transition point is identical to the transition point shown in Fig. 4 (green curves) where the tripartite concurrence reaches a maximal value. The coincidence verifies our expectation that the synchronization is maximized when the asynchronicity is minimized. Therefore, synchronization between two qubits reflects the dynamic identity of the two qubits.

Before reaching the stable minimal value, the asynchronicity increases from a non-zero value for a certain duration, which are spent on the cooperation by the qubits. When the coupling is sufficiently weak (below \(\eta \approx 200\) MHz), the minimal stable value is almost vanishing (below \(10^{-5}\)). When the coupling becomes stronger, the feedback from the cavity mode to each of the qubits becomes adverse to the synchronizing motion. However, the feedback effect is not linear. Plotted as a function of the dimensionless coupling strength \(\eta /\Omega _{A}\) at \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =6.1~\mathrm {GHz}\) and \(\Omega _{B}/2\pi =7.1~\mathrm {GHz}\) in Fig. 7, the stable minimal value \(\bar{{\mathcal {A}}}\) of asynchronicity first retains a negligible value in the weak coupling regime. At about \(\eta /\Omega _{A}=0.04\), \({\bar{\mathcal {A}}}\) starts to increase slowly until it reaches a turning point at \(\eta /\Omega _{A}=0.2\). The region between \(\eta /\Omega _{A}=0.04\) and \(\eta /\Omega _{A}=0.2\) can be regarded as a strong coupling regime for synchronization. After that, \(\bar{{\mathcal {A}}}\) enters the ultra-strong coupling regime and increases with the coupling again until \(\eta /\Omega _{A}\approx 0.33\), where stable minimal value of \({\mathcal {A}}\) is no longer discernible.

The stable value \(\bar{{\mathcal {A}}}\) is plotted as a function of the coupling strength \(\eta =\eta _{A}=\eta _{B}\) in the logarithmic dimensionless scale of \(\eta /\Omega _{A}\), where the qubit level spacings are kept at the asymmetric setting \(\Omega _{A}/2\pi =6.1~\mathrm {GHz}\) and \(\Omega _{B}/2\pi =7.1~\mathrm {GHz}\). The circles indicate the data points from the simulation runnings.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have studied the synchronization between the two cavity-coupled qubits using multiple concurrence measures and asynchronicity. These real-valued measures are computed as functionals of dressed state vectors that evolve in time as they are driven by an external field. In all these measures acting as time functions, we obtain consistent features of transitions from an arbitrary initial system state to a final synchronized state. The transition in time reveals a synchronization delay that the qubits use to initiate superfluorescent pulse radiation, which explains the cooperation origin of the collective effect of superradiance.

The characteristics of the synchronization process, including the delay and the value of the stabilized asynchronicity, are highly dependent on the coupling strengths of the qubits relative to the their level spacings. They demonstrate from the entanglement perspective the different behaviors that the circuit QED systems adopt when operating in weak, strong, and ultra-strong coupling regimes. In general, synchronization occurs only in the strong- and ultrastrong-coupling regimes whereas its level of synchronization at the final state increases exponentially with the qubit-cavity coupling strength.

Methods

For each \(3\times 3\) block submatrix of the LHS of Eq. (4), we first split it into the sum of two matrices, one being the identity matrix \(n\omega _{c}I\). The other matrix is the one to be diagonalized, the determinant equation of which is

where \(\lambda \) denotes the eigenvalue to be determined, i.e. \(E_{k}^{(n)}=\lambda +n\omega _{c}\).

This determinant equation is equivalent to the cubic equation

whose roots can be derived by absorbing the quadratic term through the transform \(\lambda =x+\delta /3\). The transformed equation becomes \(x^{3}+px+q=0\), where

In the close cavity-qubit resonance region \(\delta \thickapprox 0\), the discriminant D is simplified to

To let the cubic equation admit three non-degenerate real roots, we consider the range

that makes \(D<0\). Applying the Vieta’s formula, the roots x can be found with a parametric angle \(\theta \) given by Eq. (6).

Using the eigenvalues given in Eq. (5) and expanding the eigenvector \(\left| u_{k}^{(n)}\right\rangle \) in the bare state space given by Eq. (7), we have the column matrix equation

Letting \(\alpha _{C}\) be the proportional constant, we find \(\alpha _{A}=-\eta _{A}\alpha _{C}\Bigl /(\Delta -\lambda )\) and \(\alpha _{B}=\eta _{B}\alpha _{C}\Bigl /(\Delta +\lambda )\). Then normalizing the coefficients, their expressions are given by Eqs. (8)–(10) for the k-th energy level within the n-th cluster.

References

Pikovsky, A., Kurths, J., Rosenblum, M. & Kurths, J. Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

Acebron, J. A., Bonilla, L. L., Perez Vicente, C. J., Ritort, F. & Spigler, R. The Kuramoto model: a simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 137–185 (2005).

Shim, S.-B., Imboden, M. & Mohanty, P. Synchronized oscillation in coupled nanomechanical oscillators. Science 316, 95–99 (2007).

Vinokur, V. M. et al. Superinsulator and quantum synchronization. Nature 452, 613–615 (2008).

Zhirov, O. V. & Shepelyansky, D. L. Synchronization and bistability of a qubit coupled to a driven dissipative oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 014101 (2008).

Ying, L., Lai, Y.-C. & Grebogi, C. Quantum manifestation of a synchronization transition in optomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. A 90, 053810 (2014).

Qiao, G., Gao, H., Liu, H. & Yi, X. X. Quantum synchronization of two mechanical oscillators in coupled optomechanical systems with Kerr nonlinearity. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Heimonen, H., Kwek, L. C., Kaiser, R. & Labeyrie, G. Synchronization of a self-sustained cold-atom oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 97, 043406 (2018).

Walter, S., Nunnenkamp, A. & Bruder, C. Quantum synchronization of a driven self-sustained oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 094102 (2014).

Bonifacio, R. & Lugiato, L. A. Cooperative radiation processes in two-level systems: superfluorescence. Phys. Rev. A 11, 1507 (1975).

Bonifacio, R. & Lugiato, L. A. . Optical bistability and cooperative effects in resonance fluorescence. Phys. Rev. A 18, 1129 (1978).

Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 93, 99 (1954).

Haake, F. et al. Macroscopic quantum fluctuations in superfluorescence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 42, 1740–1743 (1979).

Polder, D., Schuurmans, M. F. H. & Vrehen, Q. H. F. Superfluorescence: quantum-mechanical derivation of Maxwell–Bloch description with fluctuating field source. Phys. Rev. A 19, 1192 (1979).

Skribanowitz, N., Herman, I. P., MacGillivray, J. C. & Feld, M. S. Observation of Dicke superradiance in optically pumped HF gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 30, 309–312 (1973).

Gibbs, H. M., Vrehen, Q. H. F. & Hikspoors, H. M. J. Single-pulse superfluorescence in cesium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 39, 547–550 (1977).

Ariunbold, G. O. et al. Observation of picosecond superfluorescent pulses in rubidium atomic vapor pumped by 100-fs laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 82, 043421 (2010).

Arecchi, F. T. & Courtens, E. Cooperative phenomena in resonant electromagnetic propagation. Phys. Rev. A 2, 1730–1737 (1970).

Abdi, M., Pirandola, S., Tombesi, P. & Vitali, D. Entanglement swapping with local certification: application to remote micromechanical resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 143601 (2012).

Tian, L. Robust photon entanglement via quantum interference in optomechanical interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 233602 (2013).

Huan, T., Zhou, R. & Ian, H. Dynamic entanglement transfer in a double-cavity optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 92, 022301 (2015).

Yokoshi, N., Odagiri, K., Ishikawa, A. & Ishihara, H. Synchronization dynamics in a designed open system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 203601 (2017).

Greilich, A. et al. Mode locking of electron spin coherences in singly charged quantum dots. Science 313, 341–345 (2006).

Mari, A., Farace, A., Didier, N., Giovannetti, V. & Fazio, R. Measures of quantum synchronization in continuous variable systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 103605 (2013).

Ollivier, H. & Zurek, W. H. Quantum discord: a measure of the quantumness of correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 017901 (2001).

Giorgi, G. L., Galve, F., Manzano, G., Colet, P. & Zambrini, R. Quantum correlations and mutual synchronization. Phys. Rev. A 85, 052101 (2012).

Wootters, W. K. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245–2248 (1998).

Coffman, V., Kundu, J. & Wootters, W. K. Phys. Rev. A 61, 052306 (2000).

Hashemi Rafsanjani, S. M., Huber, M., Broadbent, C. J. & Eberly, J. H. Genuinely multipartite concurrence of \(N\)-qubit \(X\)-matrices. Phys. Rev. A 86, 062303 (2012).

Rungta, P., Buzek, V., Caves, C. M., Hillery, M. & Milburn, G. J. Universal state inversion and concurrence in arbitrary dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 64, 042315 (2001).

Mintert, F., Kuś, M. & Buchleitner, A. Concurrence of mixed bipartite quantum states in arbitrary dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 167902 (2004).

Mintert, F., Kuś, M. & Buchleitner, A. Concurrence of mixed multipartite quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 260502 (2005).

Roulet, A. & Bruder, C. Synchronizing the smallest possible system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 053601 (2018).

Ian, H. Quasi-lattices of qubits for generating inequivalent multipartite entanglements. Europhys. Lett. 114, 50005 (2016).

Ian, H. & Liu, Y. Cavity polariton in a quasilattice of qubits and its selective radiation. Phys. Rev. A 89, 043804 (2014).

Forn-Díaz, P. et al. Ultrastrong coupling of a single artificial atom to an electromagnetic continuum in the nonperturbative regime. Nat. Phys. 13, 39–43 (2017).

Yu, T. & Eberly, J. H. Finite-time disentanglement via spontaneous emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 140404 (2004).

Mlynek, J. A., Abdumalikov, A. A., Eichler, C. & Wallraff, A. Observation of Dicke superradiance for two artificial atoms in a cavity with high decay rate. Nat. Commun. 5, 5186 (2014).

Blais, A., Huang, R.-S., Wallraff, A., Girvin, S. M. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: an architecture for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 69, 062320 (2004).

Majer, J. et al. Coupling superconducting qubits via a cavity bus. Nature 449, 443–447 (2007).

Ian, H. Stability branching induced by collective atomic recoil in an optomechanical ring cavity. New J. Phys. 19, 023052 (2017).

Fink, J. M. et al. Dressed collective qubit states and the Tavis–Cummings model in circuit QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 083601 (2009).

Hofheinz, M. et al. Synthesizing arbitrary quantum states in a superconducting resonator. Nature 459, 546–549 (2009).

Rigetti, C. et al. Superconducting qubit in a waveguide cavity with a coherence time approaching 0.1 ms. Phys. Rev. B 86, 100506 (2012).

Shankar, S. et al. Autonomously stabilized entanglement between two superconducting quantum bits. Nature 504, 419–422 (2013).

Niskanen, A. O. et al. Quantum coherent tunable coupling of superconducting qubits. Science 316, 723–726 (2007).

Acknowledgements

H.I. thanks the support by FDCT of Macau under Grant 0130/2019/A3, University of Macau under MYRG2018-00088-IAPME, and National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 11404415.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. performed the derivations and simulations. R.Z. revised the derivations. H.I. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huan, Tt., Zhou, Rg. & Ian, H. Synchronization of two cavity-coupled qubits measured by entanglement. Sci Rep 10, 12975 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69903-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69903-1

This article is cited by

-

Immobilization and Biochemical Characterization of Keratinase 2S1 onto Magnetic Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates and its Application on the Hydrolysis of Keratin Waste

Catalysis Letters (2022)

-

Distributed entanglement generation from asynchronously excited qubits

Frontiers of Physics (2022)

-

Generation of Werner-like states via a two-qubit system plunged in a thermal reservoir and their application in solving binary classification problems

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.