Abstract

We explore the phase space quantum effects, quantum coherence and non-classicality, for two coupled identical qubits with intrinsic decoherence. The two qubits are in a nonlinear interaction with a quantum field via an intensity-dependent coupling. We investigate the non-classicality via the Wigner functions. We also study the phase space information and the quantum coherence via the Q-function, Wehrl density, and Wehrl entropy. It is found that the robustness of the non-classicality for the superposition of coherent states, is highly sensitive to the coupling constants. The phase space quantum information and the matter-light quantum coherence can be controlled by the two-qubit coupling, initial cavity-field and the intrinsic decoherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum effects, quantum coherence and non-classicality, of two-level systems (qubits) are key features of quantum physics. They are operational resources, in modern applications in quantum technology1, as: quantum algorithms2, quantum computation3, and quantum key distribution4. Moreover, the quantum effects and quantum correlations have been explored, both theoretically5,6,7,8,9 and experimentally10. Recently, due to the rapid development of the real qubit systems based on the superconducting circuits11 and quantum dots12, the quantum effects have been further investigated13,14,15.

Phase-space distributions, Wigner function (WF)16 and Q-function (QF)17, are important tools to investigate the quantum effects. The WF distribution18,19 is a powerful appliance to explore the non-classicality via the positivity and negativity of the Wigner function. The negativity of WF is a sufficient but not necessary condition for non-classicality20,21,22,23. Phase space non-classicality can be visualized through the negative part of WF distribution, which cannot occur for classical light. It is a necessary and sufficient identifier for the experimental reconstruction of an entanglement quasiprobability10,24.

The QF distributions are always positive distributions25, and they are useful for exploring the phase-space information, coherence and entanglement. Entanglement and coherence26 are crucial resources for quantum information27. Based on the QF, Wehrl density and Wehrl entropy28 are introduced to quantify the phase space information and the entanglement29. These QF quantifiers were studied only for the phase space of the cavity fields, one-qubit25,29 and one-qutrit30,31. Whereas, in the multi-qubit phase space, the QF, and its applications are still in need of more investigation.

The quantum information entropies [von Neumann entropy32, linear entropy33] are used to measure the quantum coherence. Wehrl entropy delivers a valuable phase space information on the purity and the entanglement. The dynamics of the Wehrl entropy and the von Neumann entropy are very similar. Without decoherence, the von Neumann entropy, linear and Wehrl entropies of a bipartite-system are used to measure the entanglement between the two sub-systems12. Whereas, with the decoherence, the Wehrl entropy is used only to measure the phase space purity-loss of one of them34.

The quantum effects, quantum coherence and non-classicality, deteriorate due to the decoherence effects. The intrinsic decoherence (ID)35 is one of the phenomena which responsible of the coherence destruction. This ID model is previously applied to the two-qubit system in linear interaction with a cavity field36, where the intensity-dependent coupling and the coupling between the qubits are neglected.

Motivated by the important role of the phase space quantum effects, intrinsic decoherence and coherent fields in the quantum information, we introduce analytical solutions for the intrinsic decoherence model of two coupled qubits nonlinearly interacting with a coherent cavity-field. Therefore, the dynamics of the non-classicality, the phase space information and the quantum coherence will be analyzed based on the quasi-probability distributions.

In “Physical model and density matrix” section, the physical intrinsic decoherence model and the dynamics of the density matrix are presented. While the quasi-probability WF distribution is considered in “Wigner distribution” section. In “Q-distribution” section we examine the Q-distribution and its associated measures. We conclude our investigation in “Conclusion” section.

Physical model and density matrix

Hamiltonian

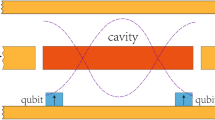

Here, we considered two coupled identical qubits that are interacting nonlinearly with a quantum cavity-field (with the same frequency \(\omega\)) via intensity-dependent coupling. This system can be realized as an artificial atomic system (such as superconducting qubits with a resonator37 or with LC circuit38), in addition to the atomic systems (such as atoms interacting with a cavity field39, nuclear spins interacting with a magnetic field40,41).

In the resonant case and using the rotating wave approximation, the Hamiltonian of the total system, in units of \(\hbar\), is

\(\hat{\sigma }^{(i)}_{\pm }\) and \(\hat{\sigma }^{(i)}_{z}\) represent the Pauli matrices which can be expressed in the bases formed by the excited states \(|e_{i}\rangle\), and ground states \(|g_{i}\rangle\) as: \(\hat{\sigma }^{(i)}_{+}=|e_{i}\rangle \langle g_{i}|\), \(\hat{\sigma }^{(i)}_{-}=|g_{i}\rangle \langle e_{i}|\) and \(\hat{\sigma }^{(i)}_{z}=|e_{i}\rangle \langle e_{i}|-|g_{i}\rangle \langle g_{i}|\). The qubits and the cavity-field have the same frequency \(\omega\). J designs the interaction coupling constant between the two qubits. The operator \(\hat{A}=\sqrt{\hat{a}^{\dag }\hat{a}}\) represents the intensity-dependent operator.

In the space states \(\{ \,|1\rangle _{n}=|e_{1}e_{2},n\rangle , |2\rangle _{n}=|e_{1}g_{2},n+1\rangle , |3\rangle _{n}=|g_{1}e_{2},n+1\rangle , |4\rangle _{n}=|g_{1}g_{2},n+2\rangle \,\}\), the dressed states \(|\Psi ^{n}_{i}\rangle\) and their eigenvalues of Eq. (1) are given by

and

with,

Intrinsic decoherence model

The dynamics of the master equation is described by35

\(\gamma\) represents the ID rate. For the sake of simplicity, we take here \(\hbar =1\).

By using Eq. (4), the dynamics of the dressed state matrices, \(\Lambda ^{mn}_{ij}(0)=|\Psi ^{m}_{i}\rangle \langle \Psi ^{n}_{j}|_{t=0}\), is given by

where, \(D_{F}=e^{-\gamma (E^{m}_{i}-E^{n}_{j})^{2}t}\) is the ID term.

We focus on the case where the initial state of the two qubits is \(\hat{\rho }^{Q_{s}}(0)=|e_{1}e_{2}\rangle \langle e_{1}e_{2}|\), and the cavity is considered initially in a superposition of coherent states,

\(|\alpha \rangle\) is the coherent state with the mean photon number \(|\alpha |^{2}\). The photon distribution function \(\eta _{n}\) is given by

where \(A=1+r^{2}+2r e^{-2|\alpha |^{2}}\). The parameter r takes the values \(-1\), 0 and 1 to get the odd coherent, coherent and even coherent states, respectively. The advantage of using the coherent states results in the fact that they are easy to be implemented and widely used in realistic physical systems42,43,44,45,46. In the dressed state representation based on the basis \(|\Psi ^{n}_{i}\rangle\) we have

From Eqs. (5) and (7), we obtain the following density matrix expression

where \(M_{ij}\) are the elements of the matrix \([\text {M}]\) of Eq. (2). The non-classicality and quantum coherence of the different system partitions, the cavity-field system \(\rho ^{C}(t)\) and the two qubits \(\hat{\rho }^{Q_{s}}(t)\), will be studied via the Wigner- and Q-distributions. The cavity-field and the two-qubit system are respectively represented, in the cavity-field system basis states \(\{|n\rangle \}\) and the two-qubit basis states \(\{|\varpi _{1}\rangle =|e_{1}e_{2}\rangle , |\varpi _{2}\rangle =|e_{1}g_{2}\rangle , |\varpi _{3}\rangle =|g_{1}e_{2}\rangle , |\varpi _{4}\rangle =|g_{1}g_{2}\rangle \}\), as:

The reduced density matrices of the k-qubit (\(k= 1, 2\)) are defined by \(\rho ^{Q_{1}(Q_{2})}(t)= \text {Tr}_{Q_{2}(Q_{1})}\{\rho ^{Q_{s}}(t)\}\).

Wigner distribution

The phase space quasi-probability distributions (QPDs) are the measure of the non-classicality for the state \(\hat{\rho }(t)\), which are defined by47,48:

If the parameter \(s=0, -1\), we get the Wigner and the Q-distributions, respectively. \(|\alpha ,n\rangle =e^{(\alpha \hat{a}^{+}-\alpha ^{*}\hat{a})}|n\rangle\) represents the displaced state number. It is known that the phase space QPDs are built on the density matrix elements. Therefore, the phase space information can be given by the QPDs.

In the representation of the field coherent state \(|\beta \rangle\), the WF of the cavity field is given by47,48,49

\(L_{n}^{m-n}(|\beta |^{2})\) represents the associated Laguerre polynomial. The positivity of the WF of a quantum state is an indicator to its minimization uncertainty, while, its negativity indicates the existence of the quantum correlation50 due to interference terms in \(W(\beta )\). It is also used to explore the classical-quantum boundary.

In Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4, the Wigner function \(W(\beta )\) \((\beta =\text {Re}\beta +i\text {Im}\beta )\) and its partial functions [as: \(W(\text {Re}\beta )\), \(W(\text {Im}\beta )\) and W(t)] of the cavity-filed system are plotted to probe the effects of the different physical parameters; Namely the effect of the non-linear interaction between the two-qubit and the cavity field, the interaction between the qubits and the intrinsic decoherence.

In Fig. 1, the behavior of the Wigner function \(W(\beta )\) of the initial even coherent state, \(\frac{1}{A}[|\alpha \rangle +|-\alpha \rangle ]\), is displayed in the phase space. In Fig. 1a, WF has symmetrical maximum and minimum. The negative and positive parts of the Wigner distribution are clearly detectable in the phase space. The negativity is the natural signature of the non-classicality.

The non-classicality disappears for larger time (see Fig. 1b).

We deduce from Fig. 2a that the generated negativity and positivity are enhanced by increasing the coupling between the two qubits. From Fig. 2b, we observe that the intrinsic decoherence has a clear effect on the Wigner distribution. The negativity and positivity of the \(W(\beta )\) function are reduced.

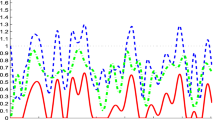

Different color curves show the effects of the two-qubit coupling and the ID rates on the partial Wigner functions \(W(\text {Re}\beta )\) and \(W(\text {Im}\beta )\). They are plotted for different cases \((J, \gamma )=(0, 0)\) (solid curves), \((J, \gamma )=(30\lambda , 0)\) (dash curves), \((J, \gamma )=(0, 0.1\lambda )\) (dash-dot curves) with \(\alpha =4\) at \(\lambda t=\pi\).

In Fig. 3, we plot the partial functions \(W(\text {Re}\beta )\) at fixed value \(\text {Im}\beta =0.06127\pi\) (see Fig. 3a), and \(W(\text {Im}\beta )\) at fixed value \(\text {Re}\beta =0\) (see Fig. 3b). This to analyze the behavior of the minimum of \(W(\beta )\) (at \(\beta _{\text {MV}}=0 + 0.06127\pi i\)).

Solid curves of Fig. 3a show the behavior of the Wigner function \(W(\text {Re}\beta )\) against the real component of complex space \(\beta\).

The Wigner function presents a pronounced non-classicalty propriety around \(\text {Re}\beta =0\), while it is purely classical out of that interval. By increasing the coupling J or the intrinsic decoherence the distinction between the classical and the quantum behaviors of the Wigner function become more noticeable.

Figure 3b, shows the dependence of the Wigner function on the imaginer component of \(\beta\) in the solid curve of \(W(\text {Im}\beta )\). It shows damped oscillator behavior around the origin. This indicates a high sensibility of the nonclassical/classical behaviors of the Wigner function to the imaginary part of the phase space parameter \(\beta\).

Figure 4 displays the dynamics of the minimum of the Wigner function: \(W(t)=W(\beta _{\text {LN}},t)\) (\(\beta _{\text {LN}}=0.009296\pi -0.06127\pi i\) (see Fig. 1a)). The dynamics of the Wigner function W(t) is quasi-periodic. We observe that: (1) The Wigner function is non classical. (2) The coupling between the two qubits leads to the increase of the negativity of W(t) with pronounced oscillations. (3) The intrinsic decoherence rate stabilizes the dynamics of the Wigner function to its stationary state (see Fig. 4b). The negativity is hypersensitive to the intrinsic decoherence and the coupling between the two qubits.

Q-distribution

Phase space information of Wehrl density (WD)

The Wehrl density is one of the applications of the Q-distribution that is used to investigate the phase space information in the coupled two qubit system. The phase space information is determined by the angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\)30,31. When the information is lost, the Wehrl density is independent of the phase space angles.

Using the basis: \(\{|\varpi _{i}\rangle \}\), the two-qubit Bloch coherent states can be written as36:

Consequently, the QF of the two-qubit system \(\rho ^{Q_{s}}(t)\) is

and its partial QFs of the k-qubit (for example for \(k=1\)) is given by

The partial Wehrl density of the k-qubit, \(D_{k}(\theta ,\phi ,t)\), is given by

Figures 5, 6 and 7 show the effects of the non-linear interaction between the two-qubit and the cavity field, the interaction between the qubits and the intrinsic decoherence, on the partial Wehrl density of the A-qubit \(D_{A}(\theta ,\phi )\).

In Fig. 5, the partial Wehrl density \(D_{A}(\theta ,\phi )\) is plotted at \(\lambda t=0\) and \(\lambda t=2.011\pi\) in the phase space for \(\alpha =4\) and \((J,\gamma )=(0, 0)\). We note that the WD function has regular oscillatory surface with \(2\pi\)-period (see Fig. 5a). Figure 5b, at \(\lambda t=2.011\pi\), illustrates that the pecks and bottoms of the partial Wehrl density \(D_{A}(\theta ,\phi )\) are regularly distributed. The contour plots of the WD function confirm the dependence of the heights and depths of the phase space WD distribution on the angular variables \(\theta\) and \(\phi\).

Figure 6a, shows that the phase space information of the Wehrl density can be controlled by the two-qubit interaction coupling. We note from Fig. 6b that the generated pecks and bottoms of the WD disappear completely due to the intrinsic decoherence.

Based on the fact that the partial Wehrl density \(D_{A}(\theta ,\phi )\) has zero-value at \(\theta =\pi\), we displays the dynamics of the Wehrl density \(D(t)=D_{A}(\theta ,\phi )\) in Fig. 7 for \((\theta , \phi )=(\pi , \pi )\). We observe that the dynamics of the Wehrl density has regular oscillations with \(2\pi\)-period. The coupling rate of the two-qubit interaction leads to smoothing and reduction of the WD oscillations. It disappears completely in the presence of the intrinsic decoherence.

Wehrl entropy

In the phase space \(\theta \in [0, \pi ]\) and \(\phi \in [0, 2\pi ]\), we can investigate the purity loss by using the Wehrl entropy28. It is a good measure to the entanglement in the sparable state and the phase space purity-loss in the mixed sate, which are useful tools in quantum information51. The partial Wehrl entropies of the k-qubit are given by

Without loss of generality, we study the Wehrl entropy coherence loss of the A-qubit by the function \(S_{A}(t)\). If the two qubits are initially prepared in the state \(|e_{A}e_{B}\rangle\),

Therefore, the boundary values of the function \(S_{A}(t)\) is30,36,

For the case of one-qubit system, there is a relation between the Wehrl entropy and the other entropies as: von Neumann entropy and linear entropy52. It was proved that they exhibit similar behaviors. The Wehrl entropy can be determined from phase-space distribution. While the von Neumann entropy is calculated from the reduced density matrix.

The Wehrl entropy, \(S_{A}(t)\) is used to measure the mixedness of the A-qubit. In Fig. 8a, the function \(S_{A}(t)\) is plotted for large value \(\alpha =4\) and for different sets of parameters: \((J, \gamma )=(0, 0)\), \((J, \gamma )=(30\lambda , 0)\) and \((J, \gamma )=(0, 0.01\lambda )\). In the absence of the intrinsic decoherence, the Wehrl entropy \(S_{A}(t)\) oscillates quasi-periodically with a \(\pi\)-period. The A-qubit is in mixed state.

Dashed curves of Fig. 8 shows how the coupling between the two qubits, \(J/\lambda\), affects the mixedness of the qubit state. The coupling constant J improves the mixedness of the qubit A. In the presence of the intrinsic decoherence, the mixdness of the A-qubit is enhanced. We also observe that the amplitudes, the regularity and the stability of the generated mixedness can be affected by the initial coherent field intensity.

Conclusion

In this investigation, we have explored analytically, two identical qubits. The two qubits are in resonant and in nonlinear interaction with a quantum field. The positivity and negativity of the Wigner distribution are explored to analyze the non-classicality. The intrinsic decoherence and the coupling between the two qubits lead to notable changes in the dynamical behavior of the non-classicality. The phase space information and the quantum coherence relay on the physical parameters. The generated mixedness can be improved by increasing the coupling between the two qubits. The growth of the Wehrl entropy, due to the cavity-qubits interaction, is enhanced by the increase of the intrinsic decoherence. The control of the non-classicality and the quantum coherence opens the door to the conception of optical states with unconventional proprieties.

Recently, the non-classicality and the quantum coherence were used to realize quantum computations53,54, quantum tomography55, quantum interference56 as well as to implement large cat states in finite-temperature reservoir57.

Change history

20 November 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Streltsov, A., Adesso, G. & Plenio, M. B. Quantum coherence as a resource. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 041003 (2017).

Shi, H.-L. et al. Coherence depletion in the Grover quantum search algorithm. Phys. Rev. A 95, 032307 (2017).

Treutlein, P., Genes, C., Hammerer, K., Poggio, M. & Rabl, P. Hybrid Mechanical Systems (Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G. & Tittel, W. & Binden, Z. H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145 (2002).

Ma, J., Yadin, B., Girolami, D., Vedral, V. & Gu, M. Converting coherence to quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 160407 (2016).

Sete, Eyob A., Eleuch, H., & Das, S. Semiconductor cavity QED with squeezed light: Nonlinear regime. Phys. Rev. A 84, 053817 (2011).

Mohamed, A.-B.A., Eleuch, H. & Raymond Ooi, C. H. Non-locality correlation in two driven qubits inside an open coherent cavity: Trace norm distance and maximum bell function. Sci. Rep. 9, 19632 (2019).

Sete, Eyob A. & Eleuch, H. High-efficiency quantum state transfer and quantum memory using a mechanical oscillator Phys. Rev. A 91, 032309 (2015)

Eleuch, H. Quantum trajectories and autocorrelation function in semiconductor microcavity. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 3, 185 (2009).

Wu, K.-D. et al. Experimental cyclic interconversion between coherence and quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 050401 (2018).

Khan, S. & Tureci, H. E. Frequency combs in a lumped-element josephson-junction ciracuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 153601 (2018).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000).

Sperling, J., Meyer-Scott, Barkhofen, E. S., Brecht, B. & Silberhorn, C. Experimental reconstruction of entanglement quasiprobabilities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 053602 (2019).

Obada, A.-S.F., Hessian, H. A. & Mohamed, A.-B.A. Entropy and entanglement in the Jaynes-Cummings model with effects of cavity damping. J. Phys. B 41, 135503 (2008).

Mohamed, A.-B.A., Eleuch, H. & Raymond Ooi, C. H. Quantum coherence and entanglement partitions for two driven quantum dots inside a coherent micro cavity. Phys. Lett. A 383, 125905 (2019).

Wigner, E. P. On the quantum correction for thermodynamic equilibrium. Phys. Rev. 47, 749 (1932).

Husimi, K. Some formal properties of the density matrix. Proc. Phys. Math. Soc. Jpn. 22, 264 (1940).

Hillery, M., O’Connell, R. F., Scully, M. O. & Wigner, E. P. Distribution functions in physics: Fundamentals. Phys. Rep. 106, 121 (1984).

Miranowicz, A., Leonski, W. & Imoto, N. Quantum-optical states in finite-dimensional Hilbert space; I. General formalism. Adv. Chem. Phys. 119, 155 (2001).

Banerji, A., Singh, R. P. & Bandyopadhyay, A. Entanglement measure using Wigner function: Case of generalized vortex state formed by multiphoton subtraction. Opt. Commun. 330, 85–90 (2014).

Mohamed, A.-B. & Eleuch, H. Non-classical effects in cavity QED containing a nonlinear optical medium and a quantum well: Entanglement and non-Gaussanity. Eur. Phys. J. D 69, 191 (2015).

Ghorbani, M., Faghihi, M. J. & Safari, H. Wigner function and entanglement dynamics of a two-atom two-mode nonlinear Jaynes-Cummings model. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 34, 1884–1893 (2017).

Ren, G. & Zhang, W. Nonclassicality of superposition of photon-added two-mode coherent states. Optik 181, 191–201 (2019).

Harder, G. et al. Local sampling of the Wigner function at telecom wavelength with loss-tolerant detection of photon statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 133601 (2016).

Bolda, E. L., Tan, S. M. & Walls, D. Exponential potentials and cosmological scaling solutions. Phys. Rev. A 57, 4686 (1998).

Baumgratz, T., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Quantifying coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 140401 (2014).

Maleki, Y. Stereographic geometry of coherence and which-path information. Opt. Lett. 44, 5513–5516 (2019).

Wehrl, A. General properties of entropy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 50, 221 (1978).

Yazdanpanah, N., Tavassoly, M. K., Juárez-Amaro, R. & Moya-Cessa, H. M. Reconstruction of quasiprobability distribution functions of the cavity field considering field and atomic decays. Opt. Commun. 400, 69–73 (2017).

Obada, A.-S.F. & Mohamed, A.-B.A. Erasing information and purity of a quantum dot via its spontaneous decay. Solid State Commun. 151, 1824–1827 (2011).

Mohamed, A.-B.A. & Eleuch, H. Coherence and information dynamics of a \(\Lambda\)-type three-level atom interacting with a damped cavity field. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 132, 75 (2017).

von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA, 1955).

Shannon, C. E. & Weaver, W. Mathematical Theory of Communication (Urbana University Press, Chicago, USA, 1949).

Obada, A.-S.F., Hessian, H. A. & Mohamed, A.-B.A. Effect of phase-damped cavity on dynamics of tangles of a nondegenerate two-photon JC model. Opt. Commun. 281, 5189–5193 (2008).

Milburn, G. J. Intrinsic decoherence in quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. A 44, 5401 (1991).

Mohamed, A.-B.A., Eleuch, H. & Obada, A.-S.F. Influence of the coupling between two qubits in an open coherent cavity: Nonclassical information via quasi-probability distributions. Entropy 21, 1137 (2019).

Zhang, J.-Q., Xiong, W., Zhang, S., Li, Y. & Feng, M. Generating the Schrodinger cat state in a nanomechanical resonator coupled to a charge qubit. Ann. Phys. 527, 180 (2015).

Johansson, J. et al. Vacuum rabi oscillations in a macroscopic superconducting qubit L C oscillator system phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 127006 (2006).

Jaynes, E. T. & Cummings, F. W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 51, 89 (1963).

Rabi, I. I. On the process of space quantization. Phys. Rev. 49, 324 (1936).

Rabi, I. I. Space quantization in a gyrating magnetic field. Phys. Rev. 51, 652 (1937).

Sanders, B. C. Review of entangled coherent states. J. Phys. A 45, 244002 (2012).

Maleki, Y. & Zheltikov, A. M. Witnessing quantum entanglement in ensembles of nitrogen-vacancy centers coupled to a superconducting resonator. Opt. Express 26, 17849 (2018).

Maleki, Y. & Zheltikov, A. M. Linear entropy of multiqutrit nonorthogonal states. Opt. Express 27, 8291 (2019).

Maleki, Y. & Zheltikov, A. M. Generating maximally-path-entangled number states in two spin ensembles coupled to a superconducting flux qubit. Phys. Rev. A 97, 012312 (2018).

Maleki, Y., Khashami, F. & Mousavi, Y. Entanglement of three-spin states in the context of SU(2) coherent states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 54, 210 (2015).

Moya-Cessa, H. & Knight, P. L. Series representation of quantum-field quasiprobabilities. Phys. Rev. A 48, 2479 (1993).

Hessian, H. A. & Mohamed, A.-B.A. Quasi-probability distribution functions for a single trapped ion interacting with a mixed laser field. Laser Phys. 18, 1217–1223 (2008).

Cahill, K. E. & Glauber, R. J. Ordered expansions in boson amplitude operators. Phys. Rev. 177, 1857 (1969).

Mohamed, A.-B.A. Long-time death of nonclassicality of a cavity field interacting with a charge qubit and its own reservoir. Phys. Lett. A 374, 4115–4119 (2010).

van Enk, S. J. & Kimble, H. J. On the classical character of control fields in quantum information processing. Quant. Inform. Comput. 2, 1 (2002).

El-Orany, Faisal A. A. Atomic Wehrl entropy for the Jaynes-Cummings model explicit form and Bloch sphere radius. J. Mod. Opt. 56, 99–103 (2009).

Strandberg, I., Lu, Y., Quijandría, F. & Johansson, G. Numerical study of Wigner negativity in one-dimensional steady-state resonance fluorescence. Phys. Rev. A 100, 063808 (2019).

Raussendorf, R., Bermejo-Vega, J., Tyhurst, E., Okay, C. & Zurel, M. Phase-space-simulation method for quantum computation with magic states on qubits. Phys. Rev. A 101, 012350 (2020).

Botelhoa, L. A. S. & Vianna, R. O. Efficient quantum tomography of two-mode Wigner functions. Eur. Phys. J. D 74, 42 (2020).

Xue, Y. et al. Controlling quantum interference in phase space with amplitude. Sci. Rep. 7, 2291 (2017).

Teh, R. Y. et al. Dynamics of transient cat states in degenerate parametric oscillation with and without nonlinear Kerr interactions. Phys. Rev. A 101, 043807 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University under the research project No. 2020/01/11801.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.-B.A.M. and H.E. contributed equally to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, AB.A., Eleuch, H. Quasi-probability information in a coupled two-qubit system interacting non-linearly with a coherent cavity under intrinsic decoherence. Sci Rep 10, 13240 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70209-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70209-5

This article is cited by

-

Dense coding, non-locality correlations and entanglement for two two-level atoms interacting resonantly with a single mode cavity field in intrinsic decoherence model

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2024)

-

Depiction of an external classical field effects on a four-level W-configuration atom embedded in a coherent cavity field

Applied Physics B (2023)

-

Synchronous observation of information loss generating among ions in a long-range Paul trap chain

Applied Physics B (2023)

-

Optical tomography dynamics induced by qubit-resonator interaction under intrinsic decoherence

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Generation of Werner-like states via a two-qubit system plunged in a thermal reservoir and their application in solving binary classification problems

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.