Abstract

Recent studies investigated the association of cardiorespiratory fitness with white matter microstructure in children, yet little work has explored to what extent other components of physical fitness (i.e., muscular or motor fitness) are associated with white matter microstructure. Indeed, this association has not been previously explored in children with overweight/obesity who present a different white matter development. Therefore, we aimed to examine associations between physical fitness components and white matter microstructure in children with overweight/obesity. In total, 104 (10.04 ± 1.15 years old; 43 girls) children were included in this cross-sectional study. Physical fitness was assessed using the ALPHA-fitness test battery. Fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity were derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). No association was found between physical fitness and global DTI metrics (all P > 0.082). Within individual tracts, all associations became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Using the voxel-wise approach, we identified a small cluster in the left lateral frontal lobe where children with greater upper-body muscular fitness showed higher FA (PFWE-corrected = 0.042). Although our results cannot conclude physical fitness is related to white matter microstructure in children with overweight/obesity; those findings indicate that the association of muscular fitness with white matter microstructure might be more focal on frontal areas of the brain, as opposed to global differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood is a critical period for neurodevelopment1, especially sensitive to a number of health-related factors that could have an influence on the brain2,3. In particular, physical fitness (i.e., the capacity to perform physical activity) is considered a powerful marker of health in children and adolescents4. Physical fitness is composed of a set of physical components such as cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e. the capacity of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems to carry out prolonged strenuous exercise), muscular fitness (i.e. the capacity to exert work against a resistance), and motor fitness (i.e. the ability to move the body as fast as possible)4. Previous evidence suggests that higher physical fitness levels are positively associated with a better physical and mental health in children and adolescents, both immediately4, 5 and later in life6,7. In addition, recent research has also shed light on the positive role of physical fitness on brain health. For instance, an American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Position Stand based on physical fitness and brain suggested that physical fitness may have a positive influence on brain structure in children2. However, few studies have explored the extent to which physical fitness is associated with white matter microstructure during childhood8,9.

White matter development includes further axon myelination via thickening of the myelin sheaths, axonal growth, and increasing calibre of fibre tracts10. Particularly, white matter is required for efficient transmission of information between brain areas into structural networks to support cognitive function and mental health11,12. To date, only two studies have examined the association between physical fitness and white matter microstructure in young people8,9. Specifically, cardiorespiratory fitness was positively associated with white matter microstructure (i.e., corpus callosum, corona radiata and superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF)) in children8; whereas among, adolescents, cardiorespiratory fitness was negatively associated with white matter microstructure in the corticospinal tract (CST)9. Apart from cardiorespiratory fitness, there are two other physical fitness components (i.e., muscular fitness and motor fitness) that have been proven to differentially influence physical and brain health during childhood4,13. However, previous studies addressing the relationship between physical fitness and white matter microstructure only focused on cardiorespiratory fitness and did not examine muscular fitness or motor fitness.

Lastly, previous literature suggests that excess body mass has been linked to a different structural connectivity14 and white matter15 development in children. For instance, compared with normal weight children, obese children showed differences in white matter organization, mainly in frontal and temporal brain regions15. However, association between physical fitness and white matter microstructure, in pediatric populations, has only been studied in normal-weight youths8,9. Taking into account the lack of studies testing the association between different components of physical fitness and white matter microstructure in children, as well as, the previously observed white matter differences in children with overweight or obesity, there is a clear need for studies that examine how different components of physical fitness (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and motor fitness) associate with white matter microstructure in younger populations, and particularly in children with overweight or obesity.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the associations of components of physical fitness with white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity. On the basis of previous literature8,9, the general hypothesis was that higher levels of physical fitness would relate to greater white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity. However, a specific hypothesis about the potential strength or anatomical location of these relationships remained open.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study is part of the ActiveBrains project (https://profith.ugr.es/activebrains?lang=en), a randomized controlled trial, with the primary aim of examining the effects of exercise on brain, cognition and academic performance in children with overweight or obesity according to sex and age specific World Obesity Federation cut-off points16,17. The complete methodology of the project has been described elsewhere18. In total, 110 children with overweight or obesity, ages 8-to-11 years, were recruited from Granada (southern Spain). Of these, 104 (10.04 ± 1.15 years old; 43 girls) were included in the present analyses. Data were collected from November 2014 to February 2016. Parents or legal guardians were informed of the goal of the study and written informed parental and child consents were obtained. This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada, and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT02295072).

Physical fitness components and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedure

Physical fitness components

Physical fitness components (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness, and motor fitness) were assessed using the extended version of the ALPHA (Assessing Levels of Physical fitness and Health in Adolescents) health-related physical fitness test battery19. This battery has been shown to be valid, reliable, feasible, and safe for the assessment of the physical fitness components in children and adolescents19.

Cardiorespiratory fitness was estimated by the 20-m shuttle-run test20. This test was always performed at the end of the fitness battery testing session. The total number of completed laps were registered. Upper- and lower-body muscular fitness were assessed using the handgrip strength test and the standing long jump test, respectively. A digital hand dynamometer with an adjustable grip (TKK 5101 Grip D, Takei, Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess upper-body muscular fitness. Each child performed the test twice, and the maximum scores of left and right hands were averaged and used as a measurement of absolute upper-body muscular fitness in kilograms (kg). The standing long jump test was performed three times and the longest jump was recorded in centimeters (cm) as a measurement of relative lower-body muscular fitness. In addition, we computed a relative-to-body weight measurement from upper body muscular fitness (kg/body weight) and an absolute measurement from lower body muscular fitness (cm * kg), according to previous research in children with obesity21. Motor fitness was assessed using the 4 × 10-m shuttle-run test. Participants were required to run back and forth twice between two lines 10-m apart. Children were instructed to run as fast as possible and every time they crossed any of the lines, they were instructed to pick up (the first time) or exchange (second and third time) a sponge that had earlier been placed behind the lines. The test was performed twice and the fastest time was recorded in seconds. Since a longer completion time indicates a lower fitness level, for analysis purposes we inverted this variable by multiplying test completion time (s) by − 1. Thus, higher scores indicated higher motor fitness levels.

Image acquisition

MRI data were collected with a 3.0 T Siemens Magnetom Tim Trio scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data were acquired using an echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3,300 ms, echo time (TE) = 90 ms, flip angle = 90, matrix = 128 × 128, field of view (FOV) = 230 mm × 230 mm, slice thickness = 4 mm, number of slices = 25 and voxel resolution = 1.8 × 1.8 × 4 mm3. One volume without diffusion weighting (b = 0 s/mm2) and 30 volumes with diffusion weighting (b = 1000 s/mm2) were collected.

Image preprocessing

DTI is able to sample features of the microstructural architecture of white matter22. To quantify total DTI metrics, we use fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD), as two of the most common derived scalar metrics from DTI23. FA expresses the degree to which water diffuses preferentially along one axis, and has shown to increase with age23 during development and to be lower in the context of various neurological and psychiatric diseases24. MD is a scalar describing the average diffusion in all directions, with higher levels indicating relatively unimpeded diffusion (i.e., negatively correlated with FA)25.

Functional MRI of the Brain Software Library (FSL) (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk) was used to processed MRI data26,27. First, images were adjusted for minor head motion28, which included a Gaussian process for outlier replacement29. Then, the resulting transformation matrices were used to rotate the diffusion gradient direction table30,31. Non-brain tissue was removed using the FSL Brain Extraction Tool32. Lastly, the diffusion tensor was fit, and common scalar maps (i.e., FA and MD) were subsequently computed.

Probabilistic fiber tractography

Fully automated probabilistic fiber tractography was performed using the FSL plugin, “AutoPtx” (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/AutoPtx). Diffusion data were processed using the Bayesian Estimation of Diffusion Parameters Obtained using Sampling Techniques (BEDPOSTx), accounting for two fiber orientations at each voxel33,34. Then, for each subject, the FA map was aligned to the FMRIB-58 FA template image with the FSL nonlinear registration tool (FNIRT). Next, the inverse of this nonlinear warp field was computed, and applied to a series of predefined seed, target, exclusion, and termination masks provided by the AutoPtx plugin35. Probabilistic fiber tracking was then execute with the FSL Probtrackx module using these supplied tract-specific masks (i.e., seed, target, etc.) that were warped to the native diffusion image space of each subject33. Lastly, the resulting path distributions were normalized to a scale from 0 to 1 using the total number of successful seed-to-target attempts and were subsequently thresholded to remove low-probability voxels likely related to noise.

White matter tract segmentation was performed by thresholding the normalized tract density images based on previously established values by de Groot et al.35 (i.e., cingulate gyrus part of cingulum (CGC): 0.01, CST: 0.005, forceps major (FMA): 0.005, forceps minor (FMI): 0.01, inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF): 0.005, SLF: 0.001, uncinate fasciculus (UNC): 0.01). Average FA and MD values were then computed for each fiber bundle. Connectivity distributions were estimated for the 7 large fiber bundles previously named and selected based on previous reports36,37,38. Average of FA and MD in the left and right hemisphere was calculated in those tracts present in both hemispheres (i.e., CGC, CST, FMA, FMI, ILF, SLF, and UNC).

To assess whether physical fitness components (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness, and motor fitness) were related to global measures of white matter microstructure (i.e., global FA, MD), selected tracts were combined into a single factor (“global factor”). The global factor was computed by averaging all tracts and weighting this average by the size (volume) of the tracts.

Tract-based spatial statistics

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) was used to perform voxel-wise statistical analyses of the DTI data (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/TBSS/UserGuide39. A mean FA image was calculated and thinned to create a mean FA skeleton, which represents the center of white matter tracts. A threshold of FA > 0.2 was selected to exclude voxels not belonging to white matter. FA maps of each participant were then projected onto the skeleton. The same procedure was applied to the MD maps.

Image quality assurance

Raw image quality was assessed via visual inspection. In addition, the sum-of-squares error (SSE) maps from the tensor estimation were calculated and visually inspected for structured noise12. Image quality was rated using a 4-point scale, with 1 = “excellent”, 2 = “minor”, 3 = “moderate”, and 4 = “severe”. Datasets determined to be of insufficient quality (i.e., moderate and severe) for statistical analyses were excluded (n = 2). Lastly, probabilistic tractography data were inspected visually. First, the native space FA map registration was inspected to ensure images were all properly aligned to the template (masks were properly mapped to native space). Second, all tracts were visualized to ensure accurate path reconstruction.

Covariates

Body weight and height were performed with participants having bare feet and wearing underclothes; weight was measured with an electronic scale (SECA 861, Hamburg, Germany) and height (cm) with a stadiometer (SECA 225, Hamburg, Germany). Both measurements were performed twice, and averages were used. BMI was expressed in kg/m2. PHV is a common indicator of maturity in children and adolescents40. PHV was obtained from anthropometric variables (weight, height and/or seated height) using Moore’s equations41. The total composite IQ was assessed by the Spanish version of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT), a validated and reliable instrument42. This test consists of vocabulary and matrices subtests which provided indicators of crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence, respectively. The typical punctuation of both, crystallized and fluid indicators of intelligence, were computed and a total intelligence score was obtained from the sum of them. Parental education was assessed by the educational level of mother and father reported (i.e., no elementary school, elementary school, middle school, high school and university completed). Parent answers were combined into a trichotomous variable (i.e., none of the parents had a university degree, one of the parents had a university degree and both parents had a university degree). Lastly, the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC), level-2 for children aged 6–12 years old, was used to assess behavioral and emotional functioning. A total behavioral symptoms index (including aggressively, hyperactivity, attention problems, atypical behaviors, anxiety and depression) was extracted from the questionnaire43.

Statistical analysis

All analyses, with the exception of TBSS analyses, were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0, Armonk, NY, P set at < 0.05). The characteristics of the study sample are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or percentages. In addition, we tested the correlation of BMI with global DTI metrics and physical fitness components. Interaction analyses of sex with physical fitness variables were also performed. No significant interactions with sex were found (P ≥ 0.10) and therefore analyses are presented for the whole sample. In addition, we explored the association of several confounders (i.e., sex, PHV, BMI, IQ, parental education, and emotional and behavioral problems) with tractography-derived white matter variables using a Pearson's bivariate correlation analysis (data no shown). Among all of the potential confounders, parental education, socioeconomic status, and emotional and behavioral problems were not significantly related to white matter microstructure (all P values > 0.1) and were therefore excluded from the subsequent analyses.

Separate linear regression analyses adjusted for sex, PHV, BMI and IQ were performed to examine the association between physical fitness components and global-extracted DTI scalar metrics (i.e., global FA and MD). Each regression model examined separately the relationships between a single physical fitness component and a single DTI scalar metric.

Then, in order to determine whether the association of physical fitness with white matter microstructure was indeed only global or restricted to a particular set of white matter bundles, and to facilitate comparison with future studies, we applied two commonly used methodologies: (1) probabilistic tractography of large, commonly studied white matter tracts and (2) TBSS, which is a voxel-based approach. For probabilistic tractography analyses, false discovery rate (FDR. Benjamini–Hochberg method) was used to adjust for multiple comparisons44. Correction for multiple comparisons was based on 7 tracts, 2 DTI metrics and 6 physical fitness components for a total of 84 tests. For TBSS analyses, the association between physical fitness components and DTI scalar metrics were tested voxel-wise using general linear models, including sex, PHV, BMI and IQ as covariates. A permutation-based statistical approach (5,000 permutations) within FSL's Randomise39 was performed including the threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) multiple comparison correction method. Significance was set at P < 0.05, corrected for family-wise error.

Results

Table 1 presents demographic participant characteristics. No correlation was found between BMI and global DTI metrics. However, a higher BMI was correlated with a lower cardiorespiratory fitness, motor fitness and relative muscular fitness (r ranges from − 0.490 to − 0.341). Of note, BMI was positively correlated with absolute muscular fitness, including upper-body muscular fitness (r = 0.276) and lower-body muscular fitness (r = 0.372). The association between physical fitness components (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness, and motor fitness) and global FA and global MD is shown in Table 2. Briefly, no associations were found between physical fitness components and any of the global white matter metrics (i.e., FA and MD) (all P values > 0.05).

Association between physical fitness components and tract-specific FA and MD is shown in Table 3. Cardiorespiratory fitness was positively associated with FA in the ILF (β = 0.273, P = 0.039). In addition, relative upper-body muscular fitness was negatively associated with MD in the ILF (β = − 0.237, P = 0.035). All these associations became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons (all P values > 0.05). No association was found between motor fitness and tract-specific FA and MD (all P values > 0.05).

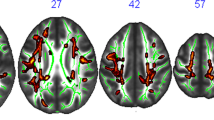

Figure 1 presents the results of the voxel-wise DTI parameter analyses (i.e. TBSS). A statistically significant positive association between absolute upper-body muscular fitness and FA in the left lateral frontal lobe (XMNI = − 25, Y = 30, Z = 34, cluster size = 13, PFWE-corrected = 0.042) was found after correction for multiple comparisons.

Positive association between absolute upper-body muscular fitness and FA in the left lateral frontal lobe (Montreal Neurological Institute—MNI-coordinates x = − 25, y = 30, z = 34; cluster size = 13; corrected P = 0.042). A = sagittal view and B = axial view. The colour bar represents P values, with yellow colour indicating higher significant association. The left hemisphere corresponds to the right side of the axial view.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the associations of physical fitness components (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness, and motor fitness) with white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity. No significant association was found between physical fitness components and global DTI scalar metrics (i.e., global FA, and global MD). Within individual tracts, all associations became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. However, results of the voxel-wise DTI parameter analyses showed that absolute upper-body muscular fitness was positively associated with FA in the left lateral frontal lobe after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Cardiorespiratory fitness was not related to global metrics of DTI (i.e., global FA, and global MD) in children with overweight or obesity. The current study found that cardiorespiratory fitness was positively associated with FA in the ILF, although this association became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. These findings were consistent with the TBBS analyses showing no association with cardiorespiratory fitness. Chaddock-Heyman et al.8, using data from the FITKids project, found that higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness were associated with greater FA in sections of the corpus callosum, corona radiata and SLF in children. These associated tracts differ from our results and may be partially explained by the different analysis approach used (i.e., Chaddock et al. used region-of-interest analyses vs. our study that used data-driven analysis adjusted for multiple comparison). In addition, measurement differences differ between the studies (e.g., different methodology of cardiorespiratory fitness assessment, differences among the MRI scanners or the MRI sequence acquisition parameters, participant demographics, participants BMI, etc.). Of note, our group, using data from the ActiveBrains and FITKids project, recently published that the white matter brain regions volumes associated with cardiorespiratory fitness were mainly located in the SLF and the ILF in children with overweight or obesity of the same approximate ages45. Consequently, although our results cannot conclude that cardiorespiratory fitness is related to white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity, these results, in line with previous literature8, seem to indicate that the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity might be more focal than global white matter, and related to long association fiber tracts.

Regarding the other two physical fitness components, both muscular and motor fitness were not related to global metrics of DTI (i.e., global FA, and global MD) in children with overweight or obesity. In addition, while motor fitness was not associated with tract-specific white matter microstructure, relative upper-body muscular fitness was negatively associated with MD in the ILF. Of note, this association became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. However, when using the TBSS approach, we identified a small cluster in the left lateral frontal lobe where children with greater absolute upper-body muscular fitness showed higher FA, after adjusting for multiple comparison. Previous literature regarding both muscular and motor fitness in relation to white matter microstructure is not available, which hampers direct comparisons with other studies. Nonetheless, in line with our results, previous studies found that adolescents with higher muscular fitness, specifically upper-body muscular fitness, had a 20–30% lower risk of death from suicide and were 15–65% less likely to have any psychiatric diagnosis such as schizophrenia and mood disorders46. In addition, it was found that higher muscular fitness during adolescence predicts lower risk of obtaining disability pension due to all causes7. Of note, our group recently published that higher upper-body muscular fitness was negatively associated with stress and negative affect, and positively associated with self-esteem in children with overweight or obesity47. Therefore, we speculate that muscular fitness plays an undefined role in white matter microstructure which in turn could mediate or moderate mental health. Future work with a larger sample should confirm or contrast this hypothesis.

The underlying plausible mechanisms of the role of muscular fitness on white matter in children with overweight or obesity cannot be elucidated in our study. However, previous literature suggested that muscle contraction induced peripheral factors (e.g., irisin, and cathepsin B) which passes through the blood–brain barrier to enhance brain-derived neurotrophic factors and hence neurogenesis, memory and learning48. However, it is unknown whether this myokine is a determining factor in muscle-induced enhanced white matter microstructure in children. It has been also suggested that exercised skeletal muscle leads to upregulation of PGC1α in mouse model and human skeletal muscle cells49. Likewise, endurance exercise training can lead to activation of the PGC1α, which stimulates the expression of kynurenine aminotransferase within skeletal muscle49. Moreover, higher expression of kynurenine aminotransferase can lead to increased conversion of neurotoxic kynurenine into neuroprotective kynurenic acid. The fact that kynurenic acid is not able to cross the blood–brain barrier protects the brain from stress-induced kynurenine accumulation, neuroinflammation and changes in synaptic plasticity. Therefore, although much still needs to be explored about the mechanisms that explain a relationship between muscular fitness and white matter microstructure in children, based on previous evidence in animal models, the positive associations between upper-body muscular fitness and greater FA in the frontal lobe is neurologically and biologically plausible.

The limitations of this study include (1) its cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to draw causal associations; (2) our focus on children with overweight or obesity, which limits the generalizability of our findings to the entire range of the BMI distribution; (3) the relatively small sample size, which could explain the few associations found in the analyses, although the sample size is respectable for neuroimaging studies in children; (4) and the voxel size which was a 4-mm-section nonisotropic voxel (1.8 × 1.8 × 4 mm3). Therefore, FA could be underestimated in regions containing crossing fibers (i.e., SLF). On the other hand, the FA measured in regions without crossing fibers (i.e., CST) is not prone to underestimation50. Lastly, the effect sizes for the association between physical fitness components and white matter microstructure were statistically non-significant or relatively small. Larger effects may not be expected due to the preservation of white matter microstructural development in the majority of young people, which probably has not yet achieved the maturational peak in most of the tracts23. Key strengths of the current study are the inclusion of neuroimaging data, and the combination of probabilistic fiber tractography and voxel-wise analyses of white matter tracts.

Conclusion

We found that physical fitness components are not associated with global DTI metrics (i.e., global FA, and global MD). Within individual tracts, all associations became non-significant when analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. However, using the TBSS approach, we identified a small cluster in the left lateral frontal lobe where children with greater absolute upper-body muscular fitness showed higher FA, after adjusting for multiple comparison. Our results cannot conclude that physical fitness components are related to white matter microstructure; however, the results seem to indicate that the association between physical fitness components (i.e., specifically muscular fitness) and white matter microstructure is more focal on specific tracts, as opposed to global differences. Future longitudinal and randomized control trials should explore the role of different physical fitness components on white matter microstructure.

References

Lenroot, R. K. & Giedd, J. N. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 718–729 (2006).

Donnelly, J. E. et al. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 48, 1197–1222 (2016).

Andersen, S. L. Trajectories of brain development: Point of vulnerability or window of opportunity?. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 27, 3–18 (2003).

Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., Castillo, M. J. & Sjöström, M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int. J. Obes. Lond. 32, 1–11 (2008).

Smith, J. J., Eather, N., Morgan, P. J. & Lubans, D. R. The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 44, 1209–1223 (2014).

Henriksson, P. et al. Physical fitness in relation to later body composition in pre-school children. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 22, 574–579 (2019).

Henriksson, H., Henriksson, P., Tynelius, P. & Ortega, F. B. Muscular weakness in adolescence is associated with disability 30 years later: a population-based cohort study of 1.2 million men. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018; 2017–098723.

Chaddock-Heyman, L. et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with greater white matter integrity in children. Front Hum Neurosci. 8, 584 (2014).

Herting, M. M., Colby, J. B., Sowell, E. R. & Nagel, B. J. White matter connectivity and aerobic fitness in male adolescents. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 7, 65–75 (2014).

Paus, T. Growth of white matter in the adolescent brain: myelin or axon?. Brain Cogn. 72, 26–35 (2010).

Schmithorst, V. J. & Yuan, W. White matter development during adolescence as shown by diffusion MRI. Brain Cogn. 72, 16–25 (2010).

Muetzel, R. L. et al. Tracking brain development and dimensional psychiatric symptoms in children: a longitudinal population-based neuroimaging study. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 54–62 (2018).

Esteban-Cornejo, I. et al. A whole brain volumetric approach in overweight/obese children: examining the association with different physical fitness components and academic performance. The ActiveBrains project. Neuroimage 159, 346–354 (2017).

Augustijn, M. J. C. M. et al. Structural connectivity and weight loss in children with obesity: a study of the “connectobese”. Int. J. Obes. 43, 2309–2321 (2019).

Ou, X., Andres, A., Pivik, R. T., Cleves, M. A. & Badger, T. M. Brain gray and white matter differences in healthy normal weight and obese children. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 42, 1205–1213 (2015).

Bervoets, L. & Massa, G. Defining morbid obesity in children based on BMI 40 at age 18 using the extended international (IOTF) cut-offs. Pediatr Obes. 9, e94–e98 (2014).

Cole, T. J. & Lobstein, T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 7, 284–294 (2012).

Cadenas-Sánchez, C. et al. An exercise-based randomized controlled trial on brain, cognition, physical health and mental health in overweight/obese children (ActiveBrains project): rationale, design and methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 47, 315–324 (2016).

Ruiz, J. R. et al. Field-based fitness assessment in young people: the ALPHA health-related fitness test battery for children and adolescents. Br. J. Sports Med. 45, 518–524 (2011).

Léger, L. A., Mercier, D., Gadoury, C. & Lambert, J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J. Sports Sci. 6, 93–101 (1988).

Thivel, D., Ring-Dimitriou, S., Weghuber, D., Frelut, M.-L. & O’Malley, G. Muscle strength and fitness in pediatric obesity: a systematic review from the European Childhood Obesity Group. Obes. Facts 9, 52–63 (2016).

Basser, P. J., Mattiello, J. & LeBihan, D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys. J. 66, 259–267 (1994).

Slater, D. A. et al. Evolution of white matter tract microstructure across the life span. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 2252–2268 (2019).

White, T. et al. Global white matter abnormalities in schizophrenia: a multisite diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 222–232 (2011).

Dennis, E. L. & Thompson, P. M. Typical and atypical brain development: a review of neuroimaging studies. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 15, 359–384 (2013).

Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W. & Smith, S. M. FSL. NeuroImage 62, 782–790 (2012).

Gorgolewski, K. et al. Nipype: a flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in Python. Front. Neuroinform. 5, 13 (2011).

Andersson, J. L. R. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 125, 1063–1078 (2016).

Andersson, J. L. R., Graham, M. S., Zsoldos, E. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. Incorporating outlier detection and replacement into a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images. Neuroimage 141, 556–572 (2016).

Jones, D. K. & Cercignani, M. Twenty-five pitfalls in the analysis of diffusion MRI data. NMR Biomed. 23, 803–820 (2010).

Leemans, A. & Jones, D. K. The B-matrix must be rotated when correcting for subject motion in DTI data. Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 1336–1349 (2009).

Smith, S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 143–155 (2002).

Behrens, T. E. J., Berg, H. J., Jbabdi, S., Rushworth, M. F. S. & Woolrich, M. W. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: what can we gain?. Neuroimage 34, 144–155 (2007).

Behrens, T. E. J. et al. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 50, 1077–1088 (2003).

De Groot, M. et al. Tract-specific white matter degeneration in aging: the Rotterdam Study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 11, 321–330 (2015).

Navas-Sánchez, F. J. et al. White matter microstructure correlates of mathematical giftedness and intelligence quotient. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 2619–2631 (2014).

Muetzel, R. L. et al. Tracking brain development and dimensional psychiatric symptoms in children: a longitudinal population-based neuroimaging study. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 54–62 (2017).

Schmithorst, V. J., Wilke, M., Dardzinski, B. J. & Holland, S. K. Cognitive functions correlate with white matter architecture in a normal pediatric population: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 26, 139–147 (2005).

Smith, S. M. et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31, 1487–1505 (2006).

Malina, R. M. et al. Biological maturation of youth athletes: assessment and implications. Br. J. Sports Med. 49, 852–859 (2015).

Moore, S. A. et al. Enhancing a somatic maturity prediction model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 47, 1755–1764 (2015).

Kaufman, A. & Kaufman, N. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (Tea, Madrid, 2000).

Reynolds, C. R. & Kamphaus, R. W. Behavior Assessment System for Children 2nd edn. (American Guidance Service, Inc., Circle Pines, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12055.

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing (1995).

Esteban-Cornejo, I. et al. Physical fitness, white matter volume and academic performance in children: findings from the ActiveBrains and FITKids2 projects. Front Psychol. 10, 208 (2019).

Ortega, F. B., Silventoinen, K., Tynelius, P. & Rasmussen, F. Muscular strength in male adolescents and premature death: cohort study of one million participants. BMJ 7279, 1–12 (2012).

Rodriguez-Ayllon, M. et al. Physical fitness and psychological health in overweight/obese children: a cross-sectional study from the ActiveBrains project. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 21, 179–184 (2017).

Pedersen, B. K. Physical activity and muscle–brain crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 383 (2019).

Agudelo, L. Z. et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1α1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and mediates resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell 159, 33–45 (2014).

Oouchi, H. et al. Diffusion anisotropy measurement of brain white matter is affected by voxel size: underestimation occurs in areas with crossing fibers. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 28, 1102–1106 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank children and parents who participated in this study. We are grateful to Ms. Ana Yara Postigo-Fuentes for assistance with the English language. This work is part of the María Rodriguez-Ayllon Ph.D. Thesis conducted in the Biomedicine Doctoral Studies of the University of Granada, Spain. This work study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (DEP2013-47540, DEP2016-79512-R, and DEP2017-91544-EXP), the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)”, the European Commission (No 667302), and the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. This study was partially funded by the University of Granada, Research and Knowledge Transfer Fund (PPIT) 2016, the Excellence Actions Programme: Units of Excellence; Scientific Unit of Excellence on Exercise and Health (UCEES), the Andalusian Regional Government, the Regional Ministry of Economy, Knowledge, Entreprises and University, and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), ref. SOMM17/6107/UGR. IE-C is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (RTI2018-095284-J-100). In addition, this study was further supported by the SAMID III network, RETICS, funded by the PN I + D + I 2017-2021 (Spain). JM-G and AP-F are supported by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (FPU14/06837, FPU 16/02760, respectively). CC-S is supported by the Government of Andalusian, Integrated Territorial Initiative 2014-2020 for the province of Cádiz (PI-0002-2017). JVR is supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (FJCI-2017-33396).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MRA, IEC, JMG, CCS, APF, PMG, FBO participated in the study design, data collection, and data interpretation. MRA, JVR, RLM were involved in the data analysis. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Esteban-Cornejo, I., Verdejo-Román, J. et al. Physical fitness and white matter microstructure in children with overweight or obesity: the ActiveBrains project. Sci Rep 10, 12469 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67996-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67996-2

This article is cited by

-

Early morning physical activity is associated with healthier white matter microstructure and happier children: the ActiveBrains project

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2024)

-

The Role of Chronic Physical Activity in Alleviating the Detrimental Relationship of Childhood Obesity on Brain and Cognition

Journal of Cognitive Enhancement (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.