Abstract

Individual lifestyle risk factors have been associated with an increased risk of mortality. However, limited evidence is available on the combined association of lifestyle risk factors with mortality in non-Western populations. The analysis included 37,472 participants (aged ≥19 years) in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (2007–2014) for whom the data were linked to death certificates/medical records through December 2016. A lifestyle risk score was created using five unhealthy behaviors: current smoking, high-risk alcohol drinking, unhealthy weight, physical inactivity, and insufficient/prolonged sleep. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). During up to 9 years of follow-up, we documented 1,057 total deaths. Compared to individuals with zero lifestyle risk factor, those with 4–5 lifestyle risk factors had 2.01 times (HR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.43–2.82) and 2.59 times (HR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.24–5.40) higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, respectively. However, higher lifestyle risk score was not significantly associated with cancer mortality (p-trend >0.05). In stratified analyses, the positive associations tended to be stronger in adults aged <65 years, unemployed, and those with lower levels of education. In conclusion, combined unhealthy lifestyle behaviors were associated with substantially increased risk of total and cardiovascular mortality in Korean adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individual lifestyle risk factors such as obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, heavy alcohol use and poor diet have been associated with increased risk of various chronic diseases and premature death1,2,3,4. More recently, insufficient or prolonged sleep has been identified as a predictor of adverse health outcomes5,6. Generally, lifestyle behaviors have complex relationships and they tend to cluster in specific combinations within populations7,8. Moreover, having multiple lifestyle risk factors can have synergistic effects on diseases. Thus, it is important to evaluate the combined effects of lifestyle factors on health outcomes to quantify disease burden and provide valuable public health messages for disease prevention.

A number of epidemiological studies have examined the combined association of major lifestyle factors including obesity, smoking, alcohol, and physical activity in relation to mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies showed that adherence to at least four healthy lifestyle behaviors was associated with a 66% reduced risk of all-cause mortality, although high heterogeneity (I2 = 94%) was observed between study populations9. Subsequent studies consistently suggested the importance of healthy lifestyle behaviors for the prevention of diseases10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. However, majority of the studies were conducted in Western populations (e.g., US and Europe). Limited data are available for non-Caucasians, especially Asians16,19,20,21 including Koreans10,12,18 whose lifestyle patterns are different from Western populations22,23. In addition, these studies had relatively small sample size and restricted study population or did not consider emerging lifestyle factors such as insufficient or prolonged sleep. Recent Korean studies also showed that major lifestyle risk factors were clustered in specific combinations for which the patterns varied by demographic/socioeconomic factors7,24.

We therefore used a large nationally representative cohort of Koreans to examine the combined association of 5 major lifestyle risk factors, including unhealthy weight, smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity and insufficient/prolonged sleep, in relation to all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality. We also examined whether the association between lifestyle risk factors and mortality differs by demographic and socioeconomic factors. Lastly, we further explored different combinations of lifestyle risk factors in relation to mortality.

Methods

Study population and database information

The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey which has been carried out since 1998 by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) to monitor health and nutritional status of Korean citizens25. The details of KNHANES are described elsewhere26. Briefly, the survey includes three parts: health examination, health interview, and nutrition survey. Upon participants’ consent, the KNHANES 2007–2015 data were linked to death certificates and medical records from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2016. All participants provided informed consent and the survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the KCDC (2007-02CON-04-P, 2008-04EXP-01-C, 2009-01COM-03-2C, 2010-02CON-21-C, 2011-02CON-06-C, 2012-01EXP-01-2C, 2013-07CON-03-4C, and 2013-12EXP-03-5C). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

To allow at least two years of follow-up, we restricted the analysis to the KNHANES 2007–2014 participants. The current analysis included the KNHANES participants who responded to the survey from 2007 to 2014 and consented to mortality follow-up. Among 59,559 participants, we excluded participants who aged <19 years (n = 14,252), those who had a history of cancer (n = 1,349) or cardiovascular disease (n = 1,855), those with missing information on lifestyle risk factors (unhealthy weight, smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity and insufficient/prolonged sleep) (n = 4,520), and those who died during the first year of follow-up (n = 111). Participants with missing information on lifestyle risk factors had similar characteristics with those included in this study (Supplementary Table 1). As a result, a total of 37,472 individuals (15,827 men, 21,645 women) were included in this study.

Mortality assessment

Date and causes of death from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2016 were ascertained by reviewing death certificates and medical records. Using the International Classification of Disease, 10th version (ICD-10), we identified all-cause mortality (n = 1,057), deaths from cardiovascular diseases (I00-I99) (n = 213) and cancers (C00-D48) (n = 347).

Lifestyle risk score

Lifestyle risk score was calculated based on the information from five different lifestyle risk factors (current smoking, high-risk alcohol drinking, unhealthy weight, physical inactivity, insufficient/prolonged sleep)13 that have been associated with increased risks of chronic diseases and mortality. Height and weight were measured at physical examination. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2) and those with BMI < 18.5 or ≥25 kg/m2 were considered unhealthy weight based on the Asia-Pacific regional guidelines of the World Health Organization27. Other lifestyle factors were assessed via health interview. Current smokers were defined as those who have smoked ≥100 cigarettes (five packs) in lifetime and reported as a current regular smoker. To rule out recent initiators, we used ≥100 cigarettes criteria to define current smokers. High-risk alcohol drinking was defined as drinking ≥14 drinks/wk for men and ≥10 drinks/wk for women during the past year13,28. Physical activity was assessed using International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)29 in 2005–2013 and Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) since 2014, which asked the average weekly total time spent on walking, moderate-intensity, and vigorous-intensity physical activity. Participants who engaged in at least 150 min/wk of moderate-intensity activity, at least 75 min/wk of vigorous-intensity activity, or a combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity were considered engaging in sufficient physical activity following the national guideline30, and those who did not meet this criteria were considered having insufficient physical activity. Insufficient/prolonged sleep (<7 or ≥9 hr/d) was defined using 7–8 hr/d sleep in the past 24 hours as the reference point31. For each of the five selected lifestyle risk factors, participants received a score of 1 if they practiced the unhealthy behavior, otherwise received a score of 0. A total lifestyle risk score ranged from 0 to 5, indicating the sum of these five scores. Higher scores indicate an unhealthier lifestyle. Because information on only few dietary factors was available for the current mortality follow-up study, we did not include dietary factors in the calculation of lifestyle risk score. In secondary analyses only, we further considered excess sodium and total dietary fat intakes (assessed via a single 24-hour recall), separately, as a dietary risk factor in score calculation. Excess sodium intake was defined as ≥2000 mg of sodium intake per day following the World Health Organization recommendation. Excess total dietary fat intake was defined as >25% of total calorie intake from dietary fat according to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in Korea. In these secondary analyses, the lifestyle risk score ranged from 0 to 6.

Statistical analysis

Participants were followed from the survey (baseline) to the date of death or to the end of follow-up on December 31, 2016, whichever occurred first. We performed Cox proportional hazards models, with age (in month) as the time metric and stratifying by the calendar year of survey, to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationships between the lifestyle risk score (0, 1, 2, 3, 4–5) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Because less than 1% of participants had all 5 lifestyle risk factors, we combined lifestyle risk scores 4 and 5. All models were adjusted for potential confounders: sex (men, women), household income (in quartiles, missing), education (<highs school, high school, college or higher, missing), occupation (white collar, blue collar, unemployed/other, missing), residential area (metropolitan area, small cities, rural areas), and marital status (married/live with a partner, unmarried/separated, missing). Potential confounders were selected a priori based on the literature on lifestyle and mortality7,9,24. Standard errors were adjusted for complex sampling design using sandwich robust variance estimation method. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by time-dependent covariate analysis. Wald test for continuous variable was used to investigate whether there was a linear trend in the association between lifestyle risk score and mortality. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate cumulative mortality according to lifestyle risk score. To examine whether the association is driven by one of the five lifestyle factors that contributed to the lifestyle risk score, we compared models excluding one lifestyle factor at a time while adjusting for the excluded factor. Moreover, we conducted stratified analyses by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (sex, age, education, income level, occupation, residential area, and marital status) and tested for interaction. In secondary analyses, we repeated the analyses after adding dietary factors (excess sodium or total dietary fat intake) in calculating lifestyle risk score and using different definition for sleep as a risk factor (considering insufficient sleep or prolonged sleep only, without grouping them together). To reduce reverse causation by subclinical diseases, we conducted a sensitivity analysis further excluding deaths occurred during the first 3 years of follow-up (n = 448). To further explore different patterns of lifestyle risk factors, we created all possible mutually exclusive combinations of the five lifestyle factors and examined their relationships with all-cause mortality.

Results

An average duration of follow-up was 6.01 years. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study participants according to lifestyle risk score. Approximately 19% of the participants had zero lifestyle risk factor and 3% had 4 or 5 lifestyle risk factors. Individuals with higher lifestyle risk score were more likely to be male, younger, and employed. Among the five selected lifestyle risk factors, the most prevalent lifestyle risk factor was insufficient/prolonged sleep (49.3%) followed by unhealthy weight (36.1%), inadequate physical activity (25.3%), smoking (21.3%) and high-risk alcohol drinking (11.5%). The Pearson correlation coefficients among the five lifestyle risk factors ranged from 0.001 to 0.28, with the highest correlation between alcohol drinking and smoking (Supplementary Table 2).

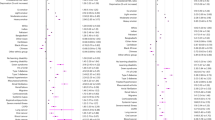

Higher lifestyle risk score was significantly positively associated with all-cause (4–5 vs. 0: HR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.43–2.82, p-trend < 0.001; Fig. 1A) and CVD mortality (4–5 vs. 0: HR = 2.59, 95% CI = 1.24–5.40, p-trend = 0.004; Fig. 1B) but not associated with cancer mortality (4–5 vs. 0: HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.18–1.43, p-trend = 0.82; Fig. 1C). The Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative all-cause and cause-specific mortality showed consistent results (Supplementary Fig. 1). When we further included sodium intake or total dietary fat intake in the score calculation, few participants practiced 5 or more lifestyle risk factors but we consistently observed a positive association with all-cause mortality (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, we found similar positive associations when using only ‘insufficient sleep’ (or ‘prolonged sleep’) instead of ‘insufficient or prolonged sleep’ (Supplementary 4).

Table 2 presents the associations between lifestyle risk score and all-cause mortality after excluding one lifestyle factor at a time. We found a statistically significant, linear positive trend with scores excluding high-risk alcohol drinking (p-trend < 0.001), unhealthy weight (p-trend < 0.001), physical activity (p-trend=0.004), or sleep duration (p-trend < 0.001). The magnitude of the positive associations became weaker after excluding current smoking, high-risk alcohol drinking, inadequate physical activity, and sleep duration.

Table 3 shows the results from stratified analyses by sex, age, education level, income level, occupation, residential area, and marital status. We observed stronger associations in adults <65 years (vs. adults ≥65 years), lower (vs. higher) education levels, unemployed (vs. employed), and single/divorced/separated (vs. married). However, the interactions were only statistically significant for education level, occupation, and marital status (p-interaction < 0.001 for all).

We also examined all combinations of five lifestyle risk factors and their associations with mortality (Supplementary Table 5). Among participants with 2 or more risk factors, the most common combinations were unhealthy weight + insufficient/prolonged sleep (9.5%), followed by inadequate physical activity + insufficient/prolonged sleep (6.1%). Among single lifestyle risk factors, the strongest positive association with all-cause mortality was shown for smoking (HR = 1.89), followed by inadequate physical activity (HR = 1.56). Among multiple lifestyle risk factor combinations, several combinations tended to show stronger associations with all-cause mortality: smoking + high-risk alcohol drinking + insufficient/prolonged sleep (HR = 2.49), high-risk alcohol drinking + inadequate physical activity + insufficient/prolonged sleep (HR = 2.49), and smoking + high-risk alcohol drinking + inadequate physical activity + insufficient/prolonged sleep (HR = 3.28). In a sensitivity analysis excluding deaths occurred during the first 3 years of follow-up, the association between lifestyle risk score and all-cause and cause-specific mortality did not change materially (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

Among 37,472 Korean men and women, having more unhealthy lifestyle risk factors was associated with considerably higher risk of mortality. Compared to Korean adults with no unhealthy lifestyle habits, those with 4 to 5 unhealthy lifestyle habits had a 2-fold higher risk of all-cause mortality and a 2.6-fold higher risk of cardiovascular mortality. In contrast, we found no association between lifestyle risk factors and cancer mortality among Korean adults. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the combined impact of major lifestyle factors on all-cause and cause-specific mortality using a large nationally representative sample of Korean adults.

A large body of existing evidence shows that being obese, physically inactive, smoking and heavy alcohol use respectively have harmful effects on diverse diseases and overall health1,2,3,4. However, relatively fewer studies have examined the combined effects of these major lifestyle factors on health outcomes9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Moreover, most of the existing studies have been conducted among Western populations (i.e., Caucasians) and found a strong inverse association between a combined healthy lifestyle habits and overall mortality. On the other hand, we identified a limited number of studies from Asian populations16,19,20,21 including three Korean studies10,12,18. A large prospective cohort followed Korean adults who participated in a medical examination at the Severance Health Promotion Center and found that having a combination of four unhealthy lifestyle factors (obesity, smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity) was associated with approximately 2-fold increased risk of total mortality10. This study did not specifically examine cardiovascular mortality, but they found similar magnitude of the associations for cancer and non-cancer mortality. Another study that included 9,945 Koreans with an average age of 60 years from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging reported similar results: compared to participants with no lifestyle risk factor, those with three or more lifestyle risk factors had 3.5- and 5.4-fold higher risk of total and cardiovascular mortality, respectively18. The Seoul Male Cohort Study used a modified lifestyle score and examined the association of 7 cardiovascular health metrics, including BMI, smoking, physical activity and diet, with mortality among middle-aged Korean men12. Although the factors included in the metric was not directly comparable to other studies, this study also suggested that healthy lifestyle habits were associated with markedly lower risk of total and cardiovascular mortality.

Beyond the traditional lifestyle factors including obesity, smoking, alcohol, and physical inactivity, our study additionally considered an emerging risk factor (‘insufficient or prolonged sleep’) in the lifestyle risk score. Recent studies have shown convincing evidence that insufficient or prolonged sleep (e.g., 6≤ or ≥10 hours) is associated with a number of chronic diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular and cancers5,6. Two cohort studies from Japan20 and Australia13 examined the combined impact of lifestyle risk behaviors including short or long sleep duration and found a positive association with mortality. Interestingly, in the Australian study, lifestyle patterns that included insufficient/prolonged sleep (e.g., physical inactivity + prolonged sitting time + long sleep/smoking + high alcohol + short sleep) showed relatively stronger positive associations than the other common risk combinations13.

In our secondary analyses, we consistently found a positive association between combined lifestyle risk score and mortality after excluding each lifestyle risk factor from the score. However, we observed greater attenuation of the association when smoking was excluded from the score, indicating that smoking is more deleterious than other lifestyle risk behaviors. We also found similar patterns when we explored different combinations of five lifestyle risk factors in relation to mortality. Among those with the same number of lifestyle risk behaviors, participants who had smoking as one of their lifestyle risk behavior tended to have higher risk of mortality. Our findings suggest that smoking cessation could be more effective strategy than other healthy lifestyle behaviors. Nevertheless, we clearly observed increased mortality risk with higher number of lifestyle risk behaviors and thus it is important to emphasize adopting overall healthy lifestyle behaviors rather than focusing on single factors to maximize the prevention of disease and premature death.

Although we considered five important lifestyle factors, our lifestyle risk score has some limitations. We did not have sufficient dietary information to evaluate overall diet quality, which is also an important lifestyle factor. Several studies have demonstrated that healthy dietary patterns were associated with lower risk of coronary heart disease and mortality in Korean adults32,33,34. Our findings (i.e., lifestyle risk score) do not fully capture the additional benefits of maintaining healthy diets. With the limited dietary information (a single 24-hour recall only), we conducted a secondary analysis further including ‘high sodium or total dietary fat intake’ as a proxy of poor diets. In this analysis, we observed a stronger but non-significant positive association with total mortality, which is likely due to a small number of participants with all six lifestyle risk factors. Given the growing number of studies showing the important role of diet35 and other modifiable factors (e.g., prolonged sitting)13 on health, more studies are needed to examine the association of comprehensive lifestyle risk score including diet quality and emerging risk factors in relation to mortality in Korean adults.

When we conducted stratified analysis, the positive association between combined lifestyle risk factors and mortality tended to be stronger in adults aged <65 years and participants with lower education and unemployed status. Intriguingly, a previous study indicated that the aforementioned groups are more susceptible to having multiple lifestyle risk factors7. These findings suggest that adherence to healthy lifestyle habits may also have greater impact on disease prevention for younger adults or those with lower socioeconomic status. There were very limited studies that thoroughly explored the associations by demographic/socioeconomic factors in Korean or other populations. This is most likely due to restricted study population and limited sample size of individual studies to perform adequate subgroup analyses. From public health perspective, it is critical to identify individuals who are more vulnerable to adverse health-related conditions that are attributable to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors for more effective and efficient lifestyle intervention targeting.

There are several strengths of the current study. First, a prospective design of the study minimizes the concern of differential misclassification. Moreover, we excluded deaths occurred during the first year of follow-up, which further reduced bias due to reverse causation. Second, this is one of few data from Asian populations and the first Korean study to examine the combined association of lifestyle risk factors and mortality using a large nationally representative sample of Koreans. Findings from this study has high generalizability. Third, we included five lifestyle risk factors including four traditional and one emerging risk factors, and they were assessed using validated methods by trained personnel. This study has limitations as well. We only used baseline lifestyle factors, and hence we were not able to capture the changes in lifestyle factors over the follow-up period. Moreover, we had a relatively short follow-up period (mean of 6 years) and limited number of deaths. Some of our analyses did not have enough power to detect significant results. Especially, our null finding for cancer mortality, which is contrary to previous studies that showed an inverse association between healthy lifestyles and cancer mortality36, can be due to limited follow-up time and number of cancer deaths, or by chance and thus should be interpreted with caution. More prospective studies with longer follow-up period are needed to reexamine cause-specific mortality in this population. Lastly, although we carefully adjusted for potential confounders, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured factors.

In conclusion, we found that unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, including smoking, heavy alcohol use, obesity, physical inactivity and insufficient/prolonged sleep, in combination were strongly associated with increased risks of total and cardiovascular mortality in Korean men and women. Interventions and strategies promoting multiple healthy lifestyle behaviors may have substantial implications to reduce chronic diseases and premature death among Korean adults.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

Ng, M. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The lancet 384, 766–781 (2014).

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 389, 1885–1906 (2017).

Lee, I.-M. et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The lancet 380, 219–229 (2012).

Rehm, J. et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The lancet 373, 2223–2233 (2009).

Liu, Y., Wheaton, A. G., Chapman, D. P. & Croft, J. B. Sleep duration and chronic diseases among US adults age 45 years and older: evidence from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep 36, 1421–1427 (2013).

Von Ruesten, A., Weikert, C., Fietze, I. & Boeing, H. Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. PloS one 7, e30972 (2012).

Ha, S., Choi, H. R. & Lee, Y. H. Clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors among Korean adults with metabolic syndrome. Plos one 12, e0174567 (2017).

Shankar, A., McMunn, A. & Steptoe, A. Health-related behaviors in older adults: relationships with socioeconomic status. American journal of preventive medicine 38, 39–46 (2010).

Loef, M. & Walach, H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive medicine 55, 163–170 (2012).

Yun, J. E., Won, S., Kimm, H. & Jee, S. H. Effects of a combined lifestyle score on 10-year mortality in Korean men and women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 12, 673 (2012).

Carlsson, A. C. et al. Seven modifiable lifestyle factors predict reduced risk for ischemic cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality regardless of body mass index: a cohort study. International journal of cardiology 168, 946–952 (2013).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Cardiovascular health metrics and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among middle-aged men in Korea: the Seoul male cohort study. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 46, 319 (2013).

Ding, D., Rogers, K., van der Ploeg, H., Stamatakis, E. & Bauman, A. E. Traditional and emerging lifestyle risk behaviors and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and older adults: evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort. PLoS medicine 12, e1001917 (2015).

Petersen, K. E. et al. The combined impact of adherence to five lifestyle factors on all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular mortality: a prospective cohort study among Danish men and women. British Journal of Nutrition 113, 849–858 (2015).

Veronese, N. et al. Combined associations of body weight and lifestyle factors with all cause and cause specific mortality in men and women: prospective cohort study. Bmj 355, i5855 (2016).

Zhang, Q.-L. et al. Combined impact of known lifestyle factors on total and cause-specific mortality among chinese men: a prospective cohort study. Scientific reports 7, 5293 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancies in the US population. Circulation 138, 345–355 (2018).

Lee, I., Kim, S. & Kang, H. Lifestyle Risk Factors and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: Data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging. International journal of environmental research and public health 16, 3040 (2019).

Nechuta, S. J. et al. Combined impact of lifestyle-related factors on total and cause-specific mortality among Chinese women: prospective cohort study. PLoS medicine 7, e1000339 (2010).

Tamakoshi, A. et al. Healthy lifestyle and preventable death: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study. Preventive medicine 48, 486–492 (2009).

Tsubono, Y. et al. Health practices and mortality in Japan: combined effects of smoking, drinking, walking and body mass index in the Miyagi Cohort Study. Journal of epidemiology 14, S39–S45 (2004).

Ford, E. S. et al. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Archives of internal medicine 169, 1355–1362 (2009).

King, D. E., Mainous, A. G. III, Carnemolla, M. & Everett, C. J. Adherence to healthy lifestyle habits in US adults, 1988–2006. The American journal of medicine 122, 528–534 (2009).

Ryu, S. Y., Park, J., Choi, S. W. & Han, M. A. Associations between socio-demographic characteristics and healthy lifestyles in Korean Adults: the result of the 2010 Community Health Survey. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 47, 113 (2014).

Kim, Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiology and health 36, e2014002, https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2014002 (2014).

Kim, Y. The Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiology and health 36 (2014).

Who, E. C. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet (London, England) 363, 157 (2004).

Health, A. G. N. & Council, M. R. (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & science in sports & exercise 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

The Physical Activity Guide for Koreans. Available at: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=032901&CONT_SEQ=337139 (2013).

Liu, T.-Z. et al. Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality: a flexible, non-linear, meta-regression of 40 prospective cohort studies. Sleep medicine reviews 32, 28–36 (2017).

Lee, J. E. et al. Dietary pattern classifications with nutrient intake and health-risk factors in Korean men. Nutrition 27, 26–33 (2011).

Lim, J. et al. An association between diet quality index for Koreans (DQI-K) and total mortality in Health Examinees Gem (HEXA-G) study. Nutrition research and practice 12, 258–264 (2018).

Oh, K.-W. et al. A case-control study on dietary quality and risk for coronary heart disease in Korean men. Journal of Nutrition and Health 36, 613–621 (2003).

Schwingshackl, L. & Hoffmann, G. Diet quality as assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension score, and health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115, 780–800. e785 (2015).

Zhang, Y.-B. et al. Combined lifestyle factors, incident cancer, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. British Journal of Cancer, 1–9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the pilot study of the “Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey linked Cause of death data’’ by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. H.O. and S.K. were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (2019R1G1A1004227, 2019S1A3A2099973) and Korea University Grant (K1808781).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.O. and J.Y.N. performed statistical analyses. D.H.L. and J.Y.N. interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. H.O. designed and conducted the research and made substantial contributions to interpretation of data, and critical revision and editing of the manuscript. S.K., N.K., J.L., M.S. made substantial contributions to interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. All authors revised manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D.H., Nam, J.Y., Kwon, S. et al. Lifestyle risk score and mortality in Korean adults: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 10, 10260 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66742-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66742-y

This article is cited by

-

Lifestyle behaviors and risk of cardiovascular disease and prognosis among individuals with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 71 prospective cohort studies

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2024)

-

The effect of alcohol consumption on all-cause mortality in 70-year-olds in the context of other lifestyle risk factors: results from the Gothenburg H70 birth cohort study

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

-

Metabo-tip: a metabolomics platform for lifestyle monitoring supporting the development of novel strategies in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine

EPMA Journal (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.