Abstract

We report the discovery of 173.4 Ma hotspot-related magmatic rocks in the basement of the Demerara Plateau, offshore French Guiana and Suriname. According to plate reconstructions, a single hotspot may be responsible for the magmatic formation of (1) both the Demerara Plateau (between 180 and 170 Ma) and the Guinea Plateau (circa 165 Ma) during the end of the Jurassic rifting of the Central Atlantic; (2) both Sierra Leone and Ceara Rises (mainly from 76 to 68 Ma) during the upper Cretaceous oceanic spreading of the Equatorial Atlantic ocean; (3) the Bathymetrists seamount chain since the upper Cretaceous. The present-day location of the inferred Sierra Leone hotspot should be 100 km west of the Knipovich Seamount.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

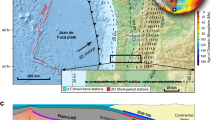

In the northern part of the Equatorial Atlantic, between the St Paul and Doldrums fracture zones, two pairs of submarine plateaus form outstanding reliefs (Fig. 1A):

(A) topography and toponomy of the northern part of the Equatorial Atlantic. (B) Demerara Plateau; (C) Sierra Leone Rise and Bathymetrists seamounts. Same scale for (B,C). Isobaths every 500 m for (A–C) (Bathymetric data from Geomapapp.org v. 3.6.10). 1D: Location (red dots) of DRADEM dredges that recovered magmatic rocks. Bathymetry (depths in meters) from GUYAPLAC10, IGUANES39 and DRADEM6 cruises.

- The Demerara and Guinea marginal plateaus, which extend seaward the continental shelf and slope offshore Suriname and French Guiana on the American side, and offshore Guinea and Guinea-Bissau on the African side;

- The Ceara and Sierra Leone rises, high standing on the abyssal plain on each side of the mid-Atlantic ridge.

The Sierra Leone and Ceara rises constitute an oceanic Large Igneous Province (LIP), formed during the upper Cretaceous at or close to the Atlantic mid-oceanic ridge, and split in two parts during the subsequent oceanic spreading1. The Sierra Leone hotspot2 has been inferred from these submarine reliefs, but its present-day location is elusive, as it has not been related to active or recent aerial or submarine volcanism.

The Demerara and Guinea marginal plateaus also represent conjugated structures, which were initially connected, before being pulled apart during the lower Cretaceous by the opening of the Equatorial Atlantic Ocean. Recent studies3,4 showed that the basement below these two marginal plateaus consists of Seaward Dipping Reflectors (SDRs), up to 20 km-thick in Demerara (Fig. 2). Those thick SDR packages suggest that the two plateaus may have formed during continental rifting as magmatic divergent margins, and may be part of a Large Igneous Province5 (approximate surface 0.15 Mkm2; volume 0.6 Mkm3 for Demerara only, calculated from seismic sections published by Reuber et al.4).

In 2016 the DRADEM oceanographic cruise6 dredged the northern slope of the Demerara Plateau in order to sample the outcropping basement. In this paper we present geochemical and dating results from two sites where magmatic rocks were recovered, and we discuss if both marginal and oceanic plateaus can be related to a single hotspot in this part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Geological setting

South of the Guinean Plateau, and East of the Demerara Plateau, the northern Equatorial Atlantic is an oceanic basin that resulted from continental rifting during the lower Cretaceous (Barremian-Aptian), and oceanic spreading since Late Aptian times7. This rift and the subsequent oceanic spreading axis connected the South Atlantic Ocean (lower Cretaceous in age) with the Central Atlantic, where oceanic spreading started during lower to middle Jurassic8. Consequently, the western edges of the Guinea and Demerara plateaus are Jurassic continental divergent margins, while the South Guinea Plateau, North and East Demerara Plateau represent Cretaceous continental margins. Furthermore, North Demerara and South Guinea plateaus are conjugated transform margins9,10, and thus both plateaus can be defined as transform marginal plateaus11. In both plateaus, the uppermost sedimentary section has been drilled (ODP Leg 20712, FG02 drillhole3,13; Fig. 1B), but the underlying basement was not sampled up until the DRADEM cruise.

The Ceara Rise is an elongated plateau, 700 km long and less than 200 km wide (Fig. 1A). Its surface is gently dipping to the north, and its southern edge is a steep slope acting as a dam that restrains the spreading of the Amazon deep sea fan. The Sierra Leone Rise is 700 km × 350 km in size, gently dipping to the northwest, with a 2 km-high steep eastern slope above the Sierra Leone abyssal plain (Fig. 1C). Geological data are very sparse in both areas. Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) sites 354 (Fig. 1A) and 366 (Fig. 1C) drilled Ceara and Sierra Leone rises, respectively. The oldest recovered sediments are Maastrichtian in age in both drill holes14. These sediments overlie basalts at sites 354, but older interlayered sediments were suggested from local high coring rates, making a common 80 Ma age likely for the initiation of magmatic accretion in both rises14. Jones et al.15 showed that abnormally thick oceanic crust (up to 17 km) underlies the Sierra Leone Rise.

Several groups of seamounts follow the northwest edge of the Sierra Leone Rise (Fig. 1C). They are aligned either in E-W or NE-SW directions. The Grimaldi seamounts follow the E-W trending Guinea Fracture Zone (Fig. 1A), which ends eastward with the transform margin south of the Guinea Plateau. Carter, Krause and Nadir seamounts belong to this chain (Fig. 1A,C). They were emplaced at 58, 54 and 59 Ma, respectively16,17,18. South of the Guinea Fracture Zone, the Bathymetrists seamounts consist of two parallel chains trending NE-SW, ending at 7°N with an E-W trending chain of seamounts (Fig. 1C). This E-W chain has been sampled by dredging, demonstrating that the seamounts are magmatic in origin, hotspot related, and capped by a carbonate platform that developed at sea-level during middle Eocene times19. The westernmost extremity of the Bathymetrists chain is the isolated Knipovitch seamount, with a horizontal quadrangular summit approximately 12 km x 6 km in size at less than 600 m water depth20. Maher et al.21 interpreted the Bathymetrists chain as a hotspot track, initiated at the Carter seamount and presently centered 160 km south of Knipovitch seamount, where it has no bathymetric expression.

Dredging sites

The DRADEM cruise6 dredged six sites along the northern slope of the Demerara Plateau. In two sites (Fig. 1D), a total of three dredges recovered the magmatic rocks on which we focus in this paper. In the other sites, the dredges recovered only sedimentary rocks.

Two dredges were operated on the northern slope of a bathymetric structure called the 60° Ridge at the northeastern edge of the Demerara plateau (Fig. 1D). This WNW-ESE-trending asymmetric ridge rises up to 3400 m deep. It stands up to 200 m above the edge of the Demerara plateau to the south, and 1200 m above the abyssal plain to the south. The average northern slope is 40°, locally 60° towards the crest of the ridge. This steepness is supposed to be inherited from the strike-slip deformation that occurred during the Cretaceous formation of this transform margin. The deep dredge (C1) was operated from 4540 to 4150 m depths, the shallower one (C2) from 4250 m to the crest of the ridge at 3400 m depths.

One dredge was operated on the northern slope of a small plateau (called Bastille Plateau) at the northeast corner of the Demerara Plateau (Fig. 1D). Bastille Plateau presents an almost flat surface at 3700 m depth, standing 300 to 400 m above the deep part of the Demarara plateau (lower plateau10), and 1000 m above the abyssal plain. The Bastille Plateau is elongated in a NW-SE direction, which is oblique relative to the regional trend of the northern edge of the Demerara plateau. Dredge E1 was operated on the northern slope of the Bastille plateau, from 4400 m up to 3740 m depth.

Results

Petrography

The three dredges recovered different types of magmatic rocks (Fig. 3):

Dredge C1 (deep part of 60° Ridge) recovered four pieces with similar lithologies. They present a porphyritic texture, with albite phenocrysts in a quartz and feldspar groundmass (Fig. 3A). Epidote and chlorite veins cut the groundmass (Fig. 3B).

Dredge C2 (shallow part of 60° Ridge) recovered a single block of volcanic rock with microlithic texture, with very few albite phenocrysts in actinote, plagioclase and chlorite mesosthasis (Fig. 3C). Millimetric amygdales are filled either with quartz crystals, or by concentric layers of epidote, quartz and chlorite (from the side to the center) (Fig. 3C). All amygdales flatten along parallel surfaces.

From their textures, these rocks are interpreted as emplaced either in the underground as magmatic stock or dykes (C1), or close to the surface (C2) where magmatic degassing can produce vacuoles, flatten during the compaction of the lava, then filled by secondary minerals. In both cases, epidote and chlorite point out greenschist metamorphic facies, likely to have occurred during post-crystallization cooling for C2, possibly during later deformation for C1. No macroscopic or microscopic sea water alterations were observed in relation to the outside surface of C1 and C2 samples.

Dredge E1 (Bastille Plateau) recovered numerous clasts of magmatic rocks, homogeneous in macroscopic examination. They present a porphyritic texture, with numerous feldspar phenocrysts (Fig. 3D–F). These magmatic rocks were strongly altered, and smectite represents 15 to 30% of the groundmass. Secondary minerals (including smectite) fill vesicles and the spaces in the feldspar lattice (Fig. 3D), suggesting the formation of palagonite from low temperature alteration of volcanic glass in contact with water. In places, one can observe some pseudomorphs of probably former pyroxene (Fig. 3F) and olivine crystals (Fig. 3E).

Geochemistry

Samples cover a wide range of compositions, from basaltic (C2) to rhyolitic (C1) for the 60° Ridge, and trachy-basalts for the Bastille Plateau (E1). SiO2 concentrations range from 45 to 73 wt%, MgO = 0.2–5.3 wt% and (Na2O + K2O) = 4.1–7.8 wt% (Table S1). Loss On Ignition (LOI) is only 0.3% for rhyolite (DRA-C1, Table S1), 2.1% for basalts (DRA-C2, Table S1), where it is probably related to epidote and chlorite that fill the vacuoles. LOI ranges from 3 to 7% for the intermediate volcanic rocks (DRA-E, Table S1), and attests to their altered nature. At least for these intermediate rocks, it is likely that major elements have somehow been modified by interactions with meteoric or seawater fluids (e.g. SiO2 leaching, attested by the negative correlation of SiO2 with the LOI: Fig. S1), and classic magmatic systematics (for example total of alkali vs SiO2) should thus be considered with extreme care. The Ti contents are high, being 3% in the basalt from 60° Ridge, from 2.7 to 4.1% (3.5% in average) in the altered trachy-basalts from Bastille Plateau (Table S1).

Trace elements also display a wide range of compositions (1 to 100 times the primitive mantle) possibly induced by various amounts of interactions with seawater. Nevertheless, rare earth element (REE) signatures (least likely fractionated by weathering processes) can be divided into two groups of almost parallel patterns (Fig. 4), suggesting a possible co-genetic link between two series of rocks. Cerium positive anomalies (Ce/Ce* = 1–2.7 with Ce* = (La+Pr)N/2 × (Ce)chondrite) (Fig. 4), could be accounted for by seawater interactions under oxidative conditions (Ce4+ being less mobile in fluids than Ce3+ and other REE), while Eu negative anomalies can be explained by plagioclase fractionation during magmatic evolution. On an extended trace element spider-diagram (Fig. 5), patterns are mostly dominated by these Ce anomalies, together with Ti, Ta and Nb enrichments. These high field strength element (HFSE) enrichments may also be related to selective leaching processes that may be responsible for the general depletion in all trace elements except for Ce4+ and HFSE. This hypothesis is supported by the correlation existing between Ce and Nb positive anomalies (quantified by Ce/Ce* and Nb/La ratios respectively) (Fig. S2); however, the extent of the HFSE positive anomaly being approximately three times higher than the Ce anomalies, it is likely that a pristine (i.e.: magmatic) enrichment in these elements was present before alteration.

Rare earth element patterns normalized to CI Chondrite60. (A,B) Samples can be divided into two groups (1 and 2) of parallel spectra (likely co-genetic). Symbols discriminate samples considering their major element compositions with rhyolites-like (SiO2 > 70%, yellow squares: C1 samples), basaltic-like (gray square: C2 sample), and intermediate compositions (orange squares: E1 samples).

All samples have mostly parallel trace element patterns, with light Rare Earth Elements (REE) enriched compared to heavy REE ((La/Yb)N = 3–6) and positive Ti, Ta and Nb (“TITAN”) anomalies (Fig. 5). These patterns are common in Oceanic Island Basalts (OIB). Even if TITAN anomalies may be accounted for by partial melting, subsequent differentiations and crustal assimilations rather than deep source compositions22, they may still be indicative of a hotspot origin for the parental magma.

Dating

We identified zircons in C1 rhyolites using a scanning electron microscope. They are less than 30 µm-long euhedral crystals, characterized by angular edges (Fig. 6A) and devoid of zonation when observed by cathodoluminescence. Fourteen 20 µm-wide laser ablation spots23,24 were performed on five zircon crystals in order to measure U/Pb isotopic compositions. They yield a lower intercept age of 173.4 ± 1.6 Ma (Fig. 6B and Table S2). This is interpreted as the crystallization age of magmatic zircons in the rhyolite, given the high Th/U ratios ranging from 0.5 to 1.3, and the absence of zonation.

Kinematic reconstruction

The thick SDR packages observed on both the Demerara and Guinea plateaus suggest that these two plateaus constituted divergent magmatic margins during the Jurassic opening of the central Atlantic, and were likely related to a mantle plume event at that time25. Moreover, the OIB-like geochemical properties of the volcanic rocks sampled in this area also point toward a hotspot connection. Consequently, we propose to further investigate this hypothesis, by searching for a secular hotspot track. The kinematic reconstruction we used is based on the global plate motion model proposed by Müller et al.26. This model is anchored to a fixed reference, such as the spin axis. It uses a hybrid absolute reference frame, based on a moving hotspot model27 for the last 70 Ma, and a true polar wander model28 from 105 to 230 Ma, including a longitudinal shift of 10◦ from 100 to 230 Ma. From 70 to 105 Ma, Müller et al.26 introduced a transition from one reference frame to the other, in order to avoid unlikely plate displacements that may be inferred from a sudden change of reference frames.

Based on the assumption that hotspots are fixed in reference to the rotation axis of the Earth, we investigated the track of a hotspot that was located beneath the Demerara Plateau 173.4 Ma ago. Using the location of C1 dredge as the center of the hotspot at 173.4 Ma, the model of Müller et al.26 reconstructs the hotspot close (less than 300 km) to the mid-Atlantic ridge from 80 to 60 Ma, at the expected time for the formation of the Ceara and Sierra Leone rises, and a present-day position north of the western end of the Bathymetrists chain (Fig. 7). The best fit with both Ceara – Sierra Leone rises and the Bathymetrists chain (Figs. 7 and 8) is provided moving the center of the hotspot 150 km SW of C1 dredge, close to the center of the SDRs mapped by Reuber et al.4 and Mercier de Lépinay3. Assuming a fixed hotspot at this location, the forward displacement of the moving plates fits with the following evidences:

Reconstructed track of the Sierra Leone hotspot. The green dots and red stars represent the track of a hotspot located on the C1 dredge or below Demerara’s SDRs at 173.4 Ma, respectively, using the kinematic model of Müller et al.26; the large star and large dot being the expected present-day locations. Green square and diamond represent the present-day location of the hotspot centered on the C1 dredge at 173.4 Ma, using the kinematic models from Seton et al.47, and Matthews et al.48, respectively. White lines represent the oceanic spreading axis closer than 250 km to the hotspot (red star) at 60, 70 and 80 Ma (see also Fig. 8). Because the hotspot is close to the spreading axis from 80 to 60 Ma (less than 100 km), its track has been reported on both Africa and South America plates. The extension of SDRs below Demerara Plateau is from Reuber et al.4 and Mercier de Lépinay3. All ages are in Ma. Bathymetric data from ETOPO2 (ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/etopo2.html) displayed using Qgis v. 2.14–3.

Track of a hotspot initially located below Demerara SDR’s at 173.4 Ma (red stars), using the kinematic model of Müller et al.26. The South America and Africa plates are almost immobile relatively to the hotspot from 180 to 170 Ma (A), during the supposed formation of the Demerara SDRs. Guinea SDRs may have formed either coeval with Demerara SDRs (A) or circa 165 Ma during the southward drift of the Africa plate above the hotspot (B). The Bahamas (B) may represent the track of the hotspot on the North America plate from 170 to 155 Ma4. The hotspot is closer than 100 km to the spreading axis from 82 to 55 Ma, with the light green surface representing the oceanic crust formed within 250 km from the hotspot (dotted circle D,E) in the same time span (thin lines in E,F are isochrones for 80, 70 and 60 Ma). In (F), the present-day 4 km isobath is superimposed for both Sierra Leone and Ceara Rises. Drawn from results using GPlates 2.0.0.

- The thickness (up to 20 km, Fig. 2) of SDRs below the Demerara Plateau can result from the fixed location of the American plate above the hotspot from 180 to 170 Ma (Fig. 8A), suggesting that the magmatism may have occurred before the emplacement of the sample C1.

- The SDRs of the Guinean Plateau3: prior to the opening of the Equatorial Atlantic, this part of the Guinean Plateau was adjacent to the Demerara Plateau (Fig. 8A,B). Unfortunately, these SDRs have not been sampled or dated, although Mercier de Lépinay3 proposed from seismic lines a Jurassic age, older to contemporaneous with the onset of oceanic spreading west of the Plateau. The SDR of Guinea may be coeval with the SDRs of Demerara (Fig. 8A), or may be formed slightly later, when the Guinean plateau moved above the hotspot from 167 to 165 Ma (Fig. 8B).

- The Ceara and Sierra Leone rises: from 82 to 55 Ma, the postulated hotspot was located less than 100 km from the mid-Atlantic ridge axis, and at the ridge axis from 76 to 68 Ma (Fig. 8D,E). During this time span, and as postulated since Kumar1, the hotspot may have thickened the oceanic crust during its spreading. Since 55 Ma ago, the ridge axis moved away from the hotspot and the oceanic spreading pulled apart the two oceanic plateaus. The part of the spreading axis being closest than 250 km to the hotspot location from 82 to 55 Ma is in good agreement with both Ceara and Sierra Leone shapes (Figs. 7 and 8F). North of Brazil, the 80 Ma isochron (Figs. 7 and 8F) fits with the abnormally thick oceanic crust29, which may represent the westernmost part of the Ceara Rise hidden by the Amazon deep sea fan. The difference in shape (more circular for Sierra Leone, elongated for Ceara) can be explained by the difference in displacement of the lithospheric plates relatively to the hotspot, the South America plate moving faster than the African one.

- The Bathymetrists chain may represent the hotspot trail. In the model of Müller et al.26, the track of the hotspot from 90 to 70 Ma follows the northern NE-SW trending part of the Bathymetrists chain (Fig. 8D,E), while it follows the southern E-W trending chain from 50 Ma to the present day (Fig. 7). The Knipovitch seamount may represent the position of the hotspot 10 Ma ago. The present-day position may be 100 km west of the Knipovitch seamount.

- In this reconstruction, the formation of the volcanoes from the Guinea Fracture Zone (Carter, Krause, Nadir) is not directly related to the hotspot, being> 500 km far from it during their formation (54–59 Ma).

Discussion

The magmatic rocks dredged during the DRADEM cruise represent a previously unknown magmatic event in this part of South America, both by their location and mid-Jurassic age (173 Ma). There are only two previously known magmatic occurrences around the Demerara Plateau. Basalts were drilled at one site on the Plateau (FG02: Fig. 2) and yielded lower Cretaceous (120–126 Ma) ages13. Onshore, numerous dykes are found in French Guiana and Suriname, dated at 196 Ma30, and were assigned to the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP)31.

Basalts and rhyolites from the 60° Ridge (dredges C1 and C2) are not significantly altered and may represent primary and differentiated members of a single magmatic suite, respectively, as frequently observed in large igneous provinces (North Atlantic: Hebrides32, Greenland33; Parana-Etendeka34; Yemen35). Because of alteration, geochemical analysis of magmatic rocks from the Bastille Plateau (dredge E1) should be used with caution. It is likely that the rocks were originally mafic in composition. They share similar REE compositions with 60° Ridge samples, making a common origin possible, although they may be representative of a distinct temporal and/or source magmatic event. It is also noteworthy that all the dredged magmatic rocks have similar REE patterns (Fig. 4) and high-Ti contents (for the mafic rocks: Table S1) with the CAMP-related Guiana tholeiites36 and Sierra Leone intrusions37,38, which are more than 20 Ma older.

Unfortunately, the available seismic lines (GUYAPLAC10 and IGUANES39 cruises) do not permit a robust connection between the outcropping slopes and the SDRs identified and mapped by Reuber et al.4 and Mercier de Lépinay3, implying that their geometrical relationships remain unconstrained. However, SDR formation is older than the upper Jurassic, and sub-contemporaneous with the onset of oceanic spreading west of Demerara3,4, which should have occurred circa 170 Ma8. The age measured from the rhyolite (base of Middle Jurassic: 173.4 Ma) fits well with these stratigraphic constraints. We therefore propose that the dredged magmatic rocks belong to the SDR package. This interpretation brings together OIB lavas and SDRs, as commonly observed along magmatic divergent margins40.

The connection between a large igneous province and a hotspot track should demonstrate secular evolution and thus kinematic models should also be correlative. For example, Maia et al.41 or Le Voyer et al.42 suggest the Sierra Leone hotspot was located close to the St Peter and St Paul islets, based on Schilling et al.43 who used Duncan and Richards44 and Cande et al.45 to extrapolate the present-day location from the vicinity of a fixed hotspot with the mid-Atlantic ridge 75 Ma ago.

In this paper we used the kinematic reconstruction from Müller et al.26 to localize the past position of the Sierra Leone hotspot, and not as a proof of its track. However, as the uncertainties are low for recent times, and hotspot fixity is not discernable from uncertainties46, the recent track (<70 Ma for Müller et al.26) can be used with relative confidence. The track older than 70 Ma is mainly controlled by the correction in longitude applied in the model, explaining the large discrepancies between different models using various corrections: a fixed hotspot below the 60° Ridge at 173.4 Ma results in a present-day location in the Sierra Leone abyssal plain for Seton et al.47, or on the western edge of the Guinea Plateau for Matthews et al.48, both being more than 1000 km East or Northeast of Muller’s position (Fig. 7). Both Seton et al.47 and Matthews et al.48 reconstructions fail to explain the building of the Ceara and Sierra Leone rises with a hotspot location below Demarara at 173.4 Ma.

Therefore, Müller et al.26 kinematic reconstruction succeeds in connecting a single hotspot, namely the Sierra Leone hotspot, to the creation of both pairs of plateaus: that is, the Demerara and Guinea marginal plateaus during lower to middle Jurassic times, and Ceara and Sierra Leone oceanic plateaus during the upper Cretaceous times. Extending back in time the same kinematic model and the same assumptions of stationarity of hotspots brings the postulated Sierra Leone hotspot north of the Blake Plateau49, offshore South Carolina, and below the SDRs of the Carolina trough and the Blake Plateau49,50. In other words, the hotspot was located at the center of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) 201 Ma ago, at the intersection point between the CAMP-related dykes of Africa, North and South America51,52. Burke and Torsvik2 and Ruiz-Martinez et al.53 previously noticed this coincidence between reconstructed locations of the Sierra Leone hotspot and the CAMP. Although the age of the SDRs from the Carolina trough and the Blake Plateau is debated54, they appear to pre-date the onset of oceanic spreading, circa 190 Ma8. Hence a single hotspot may have formed successive sets of SDRs during the southward propagation of the Central Atlantic, from 200–190 Ma along the east coast of North America to 180–170 Ma in Demerara, at the southernmost tip of the Central Atlantic.

However, the duration of hotspot magmatism comes into question. Some of the hotspots were proposed to be perennial since Mesozoic times: Golonka and Bocharova55 proposed to identify the Permo-Triassic Siberian traps with the Iceland hotspot, the Karoo-Ferrar Middle Jurassic LIP with the Bouvet hotspot, and the opening of the Central Atlantic (i.e. the CAMP) with the Sierra Leone hotspot. Here, we suggest a duration of up to 180 Ma (possibly 200 Ma) for the Sierra Leone hotspot. However, its surface expression appears to be mainly controlled by the plate tectonic setting: marginal plateaus (Demerara and Guinea) as oceanic plateaus (Ceara and Sierra Leone) formed by eruption or intrusion of large volumes of magmas when the hotspot was located below a divergent plate boundary, either during the Jurassic rifting of the Central Atlantic, or during the Cretaceous oceanic spreading in the Equatorial Atlantic. We interpret the western part of the Bathymetrists seamounts to represent the morphologic expression of the hotspot track below oceanic lithosphere in intraplate setting, with the Knipovitch seamount interpreted as the most recent volcano, expected to be 10 Ma-old.

On the contrary, the hotspot track does not clearly extend to the continental lithosphere. The Sierra Leone hotspot is expected to have stayed for a long time (from middle Jurassic to the end of Lower Cretaceous, Fig. 8B,C) below the continental margin of the West Africa, where volcanic remnants should be buried below a thick sedimentary cover. Volcanic remnants dated 104–106 Ma offshore Guinea (Los island syenites56 and drilled offshore trachytes57) may however be related to the vicinity of the hotspot (Fig. 8C).

Conclusions

The main result of this study is the discovery of Middle Jurassic (173.4 Ma) magmatism on the northern edge of the Demerara Plateau. The magmatic suite includes mafic (basalts) and differentiated (rhyolites) rocks. Trace element patterns indicate that the basaltic rocks are similar to ocean island basalts (OIB). The magmatism is interpreted to be part of the SDRs observed in the basement of the Demerara Plateau. It supports the previous conclusions of seismic line analysis3,4, concluding that the Demerara Plateau formed during the Jurassic as a magmatic divergent margin at the edge of the Central Atlantic. The OIB-type and the SDRs suggest that this Jurassic magmatism is associated with a hotspot track. Kinematic reconstruction26 allows us to connect the Middle Jurassic creation of the Demerara and conjugated Guinea marginal plateaus, the Upper Cretaceous building of conjugated Ceara and Sierra Leone oceanic plateaus, and the Cenozoic Bathymetrists seamount chain, to a single hotspot track, namely the Sierra Leone hotspot. The last topographic remnant of the hotspot track should be the Knipovitch seamount that we think formed 10 million years ago.

Methods

For geochemical analysis, rock samples were crushed with a stainless steel jaw crusher and then powdered in an agate swing mill. Major element concentrations were obtained using an ICP-AES Jovin Yvon Ultima 2 at University of Brest, after a HF-HNO3 digestion as described in Cotten et al.58. Trace element concentrations were measured with a Thermo Element2 HR-ICP-MS in Brest, after a repeated HF-HClO4 digestion, and HNO3 dilutions (see Mougel et al.59 for details). The repeated analysis of the international standards BHVO2, BCR2 and BIR1 demonstrated an external reproducibility of better than 2–10% depending on the element and concentration, with the exception of Pb (reproducibility 9–25%) (Fig. S4 and Table S1).

References

Kumar, N. Origin of “paired” aseismic rises: Cearà and Sierra Leone rises in the Equatorial, and the Rio Grande Rise and Walvis Ridge in the South Atlantic. Marine Geology 30, 175–191, https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(79)90014-8 (1979).

Burke, K. & Torsvik, T. H. Derivation of Large Igneous Provinces of the past 200 million years from long-term heterogeneities in the deep mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 227, 531–538, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.015 (2004).

Mercier de Lépinay, M. Inventaire mondial des marges transformantes et évolution tectono-sédimentaire des plateaux de Demerara et de Guinée. Ph. D. thesis, University of Perpignan, 335 p. (2016).

Reuber, K. R., Pindell, J. & Horn, B. W. Demerara Rise, offshore Suriname: magma-rich segment of the Central Atlantic Ocean, and conjugate to the Bahamas hot spot. Interpretation 4, T141–T155, https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2014-0246.1 (2016).

Bryan, S. E. & Ernst, R. E. Revised definition of Large Igneous Province (LIPs). Earth-Science Reviews 86, 175–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2007.08.008 (2008).

Basile, C., Girault, I., Heuret, A., Loncke, L. & Poetisi, E. DRADEM campaign, scientific report., https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01418119 (2016).

Basile, C., Mascle, J. & Guiraud, R. Phanerozoic geological evolution of the Equatorial Atlantic domain. Journal of African Earth Sciences 43, 275–282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.011 (2005).

Labails, C., Olivet, J. L., Aslanian, D. & Roest, W. R. An alternative early opening scenario for the Central Atlantic Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 297, 355–368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.06.024 (2010).

Benkhelil, J., Mascle, J. & Tricart, P. The Guinea continental margin: an example of a structurally complex transform margin. Tectonophysics 248, 117–137, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(94)00246-6 (1995).

Basile, C. et al. Structure and evolution of the Demerara Plateau, offshore French Guiana: Rifting, tectonic inversion and post-rift tilting at transform-divergent margins intersection. Tectonophysics 591, 16–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2012.01.010 (2013).

Loncke, L. et al. Transform marginal plateaus. Earth-Science Reviews (in press)., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102940

Mosher, D. C., Erbacher, J. & Malone, M. J. (Eds.). Proc. ODP, Sci. Results, 207 (2007). College Station, TX, https://doi.org/10.2973/odp.proc.sr.207.2007.(Ocean Drilling Program).

Gouyet, S., Unternehr, P. & Mascle, A. The French Guyana margin and the Demerara Plateau: geological history and petroleum plays, in Mascle, A., ed., Hydrocarbon and petroleum geology of France: Springer-Verlag, 411–422 (1994).

Supko, P.R, & Perch-Nielsen, K. General synthesis of Central and South Atlantic drilling results, Leg 39. Deep Sea Drilling Project: Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project: 39, 1099-1131 (1977). U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington D.C, https://doi.org/10.2973/dsdp.proc.39.146.1977.

Jones, E. J. W., McMechan, G. A. & Zeng, X. Seismic evidence for crustal underplating beneath a large igneous province: The Sierra Leone Rise, equatorial Atlantic. Marine Geology 365, 52–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.03.008 (2015).

Skolotnev, S. G., Petrova, V. V. & Peyve, A. A. Origin of submarine volcanism at the Eastern margin of the Central Atlantic: investigation of the alkaline volcanic rocks of the Carter seamount (Grimaldi seamounts). Petrology 20, 59–85, https://doi.org/10.1134/S086959111106004X (2012).

Jones, E. J. W., Goddard, D. A., Mitchell, J. G. & Banner, F. T. Lamprophyric volcanism of Cenozoic age on the Sierra Leone Rise: implications for regional tectonics and the stratigraphic time scale. Mar. Geol. 99, 19–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(91)90080-N (1991).

Bertrand, H., Féraud, G. & Mascle, J. Alkaline volcano of Paleocene age on the Southern Guinean margin: mapping, petrology, 40Ar-39Ar laser probe dating, and implications for the evolution of the Eastern Equatorial Atlantic. Mar. Geol. 114, 251–262, https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(93)90031-P (1993).

Skolotnev, S. G., Peyve, A. A., Bylinskaya, M. E. & Golovina, L. A. New data on the composition and age of rocks from the Bathymetrists seamounts (eastern margin of the Equatorial Atlantic). Doklady Earth Sciences 472, 20–25, https://doi.org/10.1134/S1028334X17010160 (2017).

Robinson, L.F. Reconstructing abrupt changes in chemistry and circulation of the Equatorial Atlantic Ocean: implications for global Climate and deep-water habitats. RRS James Cook Cruise JC094 report, bodc.ac.uk/resources/inventories/cruise_inventory/reports/jc094.pdf (2014).

Maher, S. M., Wessel, P., Müller, R. D., Williams, S. E. & Harada, Y. Absolute plate motion of Africa around Hawaii-Emperor bend time. Geophysical Journal International 201, 1743–1764, https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggv104 (2015).

Peters, B. J. & Day, J. M. D. Assessment of relative Ti, Ta, and Nb (TITAN) enrichments in ocean island basalts. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15, 4424–4444, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005506 (2014).

Paquette, J. L., Piro, J. L., Devidal, J. L., Bosse, V. & Didier, A. Sensitivity enhancement in LA-ICP-MS by N2 addition to carrier gas: application to radiometric dating of U-Th-bearing minerals. Agilent ICP-MS J. 58, 4–5 (2014).

Paquette, J. L., Ionov, D. A., Agashev, A. M., Gannoun, A. & Nikolenko, E. I. Age, provenance and Precambrian evolution of the Anabar shield from U-Pb and Lu-Hf isotope data on detrital zircons, and the history of the northern and central Siberian craton. Precamb. Res. 301, 134–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2017.09.008 (2017).

Courtillot, V., Jaupart, C., Manighetti, I., Tapponnier, P. & Besse, J. On causal links between flood basalts and continental breakup. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 166, 177–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00282-9 (1999).

Müller, R. D. et al. Ocean basin evolution and global-scale plate reorganization events since Pangea breakup. Annual Review Earth Planetary Science 44, 107–138, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012211 (2016).

Torsvik, T. H. & Müller, D. T. Van der Voo, R., Steinberger, B. & Gaina, C. Global plate motion frames: toward a unified model. Reviews of Geophysics 46, RG3004, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007RG000227 (2008).

Steinberger, B. & Torsvik, T. H. Absolute plate motions and true polar wander in the absence of hotspot tracks. Nature 452, 620–623, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06824 (2008).

Rodger, M., Watts, A. B., Greenroyd, C. J., Peirce, C. & Hobbs, R. W. Evidence for unusually thin ocean crust and strong mantle beneath the Amazon Fan. Geology 34(12), 1081–1084, https://doi.org/10.1130/G22966A (2006).

Deckart, K., Féraud, G. & Bertrand, H. Age of Jurassic continental tholeiites of French Guyana, Surinam and Guinea: implications for the initial opening of the Central Atlantic Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 150, 205–220, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(97)00102-7 (1997).

Marzoli, A. et al. Extensive 200-Million-Year-old continental flood basalts of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province. Science 284, 616–618, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.284.5414.616 (1999).

Walsh, J. N., Beckinsale, R. D., Skelhorn, R. R. & Thorpe, R. S. Geochemistry and petrogenesis of Tertiary granitic rocks from the Island of Mull, Northwest Scotland. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 71, 99–116, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00375426 (1979).

Brooks, C. K. The East Greenland rifted volcanic margin. Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland Bulletin 24, 96 pp. (2011).

Peate, D.W. The Parana-Etendeka Province. In: Large Igneous Provinces: continental, oceanic and planetary flood volcanism. Mahoney, J. J. & Coffin, M. F. (eds). Geophysical monograph 100, 217–245 (1997).

Menzies, M., Baker, J. & Chazot, G. Cenozoic plume evolution and flood basalts in Yemen: a key to understanding other examples. In: Mantle plumes: their identification through time. Ernst, R.E & Buchan, K.L. (eds.). Geological Society of America, Special Paper 352, 23-36 (2001).

Deckart, K., Bertrand, H. & Liégeois, J. P. Geochemistry and Sr, Nd, Pb isotopic composition of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) in Guyana and Guinea. Lithos 82, 289–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2004.09.023 (2005).

Callegaro, S. et al. Geochemical constraints provided by the Freetown Layered Complex (Sierra Leone) on the origin of High-Ti Tholeiitic CAMP magmas. Journal of Petrology 58, 1811–1840, https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egx073 (2017).

Marzoli, A. et al. The Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP): A review. In Tanner, L.H. (ed), The late Triassic world, topics in Geobiology 46, Springer, 91–125, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68009-5_4 (2018).

Loncke, L. et al. Structure of the Demerara passive-transform margin and associated sedimentary processes. Initial results from the IGUANES cruise. In Transform margins: development, controls and petroleum systems. Nemcok, M., Rybar, S., Sinha, S.T., Hermeston, S.A & Ledvenyiova, L. (eds). Geological Society, London, Special publications 431, 19 p. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1144/SP431.7

Agranier, A. et al. Volcanic record of continental thinning in Baffin Bay margins: insights from Svartenhuk Halvo Peninsula basalts, West Greenland. Lithos 334-335, 117–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2019.03.017 (2019).

Maia, M. et al. Extreme mantle uplift and exhumation along a transpressive transform fault. Nature Geoscience 9, 619–623, https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2759 (2016).

Le Voyer, M., Cottrell, E., Kelley, K. A., Brounce, M. & Hauri, E. H. The effect of primary versus secondary processes on the volatile content of MORB glasses: an example from the equatorial Mid-Atlantic Ridge (5°N-3°S). Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 120, 125–144, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011160 (2015).

Schilling, J.-G., Hanan, B. B., McCully, M. & Kingsley, R. H. Influence of the Sierra Leone mantle plume on the equatorial Mid-Atlantic Ridge: a Nd-Sr-Pb isotopic study. Journal of Geophysical Research 99(B6), 12005–12028, https://doi.org/10.1029/94JB00337 (1994).

Duncan, R. A. & Richards, M. A. Hotspots, mantle plumes, flood basalts, and true polar wander. Reviews of Geophysics 29, 31–50, https://doi.org/10.1029/90RG02372 (1991).

Cande, S., LaBrecque, J. L. & Haxby, W. B. Plate kinematics of the South Atlantic: Chron 34 to present. Journal of Geophysical Research 93, 13479–13492, https://doi.org/10.1029/JB093iB11p13479 (1988).

O’Neill, C., Müller, D. & Steinberger, B. On the uncertainties in hot spot reconstructions and the significance of moving hot spot reference frames. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, Q04003, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GC000784 (2005).

Seton, M. et al. Global continental and ocean basin reconstructions since 200 Ma. Earth-Sci. Rev. 113, 212–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.03.002 (2012).

Matthews, K. J. et al. Global plate boundary evolution and kinematics since the late Paleozoic. Global and Planetary Change 146, 226–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.10.002 (2016).

Oh, J., Austin, J. A., Phillips, J. D., Coffin, M. F. & Stoffa, P. L. Seaward-dipping reflectors offshore the southeastern United States: Seismic evidence for extensive volcanism accompanying sequential formation of the Carolina trough and Blake Plateau basin. Geology 23, 9–12, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023 (1995).

Austin, J. A. et al. Crustal structure of the Southeast Georgia embayment-Carolina trough: Preliminary results of a composite seismic image of a continental suture (?) and a volcanic passive margin. Geology 18, 1023–1027, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018 (1990).

May, P. R. Pattern of Triassic-Jurassic diabase dikes around the North Atlantic in the context of predrift position of the continents. Geological Society of America Bulletin 82, 1285–1292, https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[1285:POTDDA]2.0.CO;2 (1971).

Ernst, R. E., Head, J. X., Parfitt, E., Grosfils, E. & Wilson, L. Giant radiating dyke swarms on Earth and Venus. Earth-Sci. Rev. 39, 1–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252(95)00017-5 (1995).

Ruiz-Martinez, V. C., Torsvik, T. H., van Hinsbergen, D. J. J. & Gaina, C. Earth at 200 Ma: Global palaeogeography refined from CAMP palaeomagnetic data. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 331-332, 67–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.03.008 (2012).

Heffner, D. M., Knapp, J. H., Akintunde, O. M. & Knapp, C. C. Preserved extend of Jurassic flood basalt in the South Georgia Rift: A new interpretation of the J horizon. Geology 40, 167–190, https://doi.org/10.1130/G32638.1 (2012).

Golonka, J. & Bocharova, N. Y. Hot spot activity and the break-up of Pangea. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 161, 49–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00117-6 (2000).

Moreau, C., Ohnenstetter, D., Demaiffe, D. & Robineau, B. The Los archipelago nepheline syenite ring-structure: a magmatic marker of the evolution of the Central and Equatorial Atlantic. Can. Mineral. 34, 281–299 (1998).

Olyphant, J. R., Johnson, R. A. & Hughes, A. N. Evolution of the Southern Guinea Plateau: implications on Guinea-Demerara Plateau formation using insights from seismic, subsidence, and gravity data. Tectonophysics 717, 358–371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2017.08.036 (2017).

Cotten, J. et al. Origin of anomalous rare-earth element and yttrium enrichments in subaerially exposed basalts - evidence from French Polynesia. Chem. Geol. 119, 115–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)00102-E (1995).

Mougel, B., Agranier, A., Hemond, C. & Gente, P. A highly unradiogenic lead isotopic signature revealed by volcanic rocks from the East Pacific Rise. Nature Comm. 5, 4474, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5474 (2014).

McDonough, W. F. & Sun, S. S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253, https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)00140-4 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the crew and officers of the Pourquoi Pas ? for their commitment during the DRADEM cruise, the Ifremer staff, W. Roest and D. Graindorge for their help in the preparation of the cruise, and the Suriname and French Guiana authorities for allowing the cruise to be performed in their Exclusive Economic Zones. Nathaniel Findling provided help with the scanning Electron Microscope. This work has been supported by Ifremer, INSU, Labex OSUG@2020, ISTerre, CEFREM and Géosciences Océan. Anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Basile, I. Girault, L. Loncke, A. Heuret and E. Poetisi were the scientific team onboard the Research Vessel Pourquoi Pas? during DRADEM cruise (2016), that collected the rock samples. C. Basile was the chief scientist for the cruise. I. Giraud analyzed the samples on thin section (Fig. 3) and on SEM, and localized the zircons. J.L. Paquette performed the U/Pb isotopic analysis and dated the zircons, and wrote the associated part together with Fig. 6. A. Agranier performed and interpreted the geochemical analysis (figs. 4 and 5), wrote the associated part of the manuscript and Supplementary Materials. C. Basile performed the kinematic reconstructions, wrote the first draft and drew the first draft of Figs. 1, 2 and 7 and 8. All contributed to writing and drawing for the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basile, C., Girault, I., Paquette, JL. et al. The Jurassic magmatism of the Demerara Plateau (offshore French Guiana) as a remnant of the Sierra Leone hotspot during the Atlantic rifting. Sci Rep 10, 7486 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64333-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64333-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.