Abstract

We elucidate the evolution of the entrained air in drop impact on a wide range of liquids, using ultrafast X-ray phase-contrast imaging. We elaborate the retraction mechanism of the entrapped air film in terms of liquid viscosity. We found the criterion for deciding if the entrapped air evolves into single or double bubbles, as determined by competition among inertia, capillarity, and viscosity. Low viscosity and low surface tension induce a small daughter droplet encapsulated by a larger air shell bubble, forming an antibubble. We demonstrate a phase diagram for air evolution regarding hydrodynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drop impact on a liquid surface has great importance in many natural and industrial processes. Raindrops or breaking waves can entrain small air bubbles when they fall onto the sea. This process is a crucial mechanism of gas transport from the atmosphere to the ocean and plays a crucial role in climate change and the ecosystem1,2,3,4, and also of great interest in fundamental science and technology. For example, entrapped bubbles can produce underwater noises by their oscillation or enhance nucleate boiling in chemical processes5,6,7. On solid substrates, air entrapment in drop impact has been actively studied8,9,10,11,12,13,14. The air underneath an impacting drop fails to drain and is instead compressed, deforming the bottom surface of the drop. The air layer ruptures thereby, resulting in the entrapment of an air film, eventually evolving into formation of a bubble11,12,13,14. On liquid surfaces, however, the evolution of the air entrapment has been largely unexplored because of difficulty in visualizing its microscale (<100 μm), rapid (<100 μs), and complex dynamics15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. In particular, there is currently no physical model that exactly predicts the morphology of the entrapped bubble in a wide range of liquid properties and impact conditions.

In this paper, we studied the evolution of the air entrained by drop impact on a variety of liquid pools by using high-speed X-ray phase-contrast imaging that enables us to clearly track the rapid evolution of the interfaces in high temporal (~μs) and spatial (~μs) resolutions. The retraction mechanism of an entrapped air film is elaborated in terms of liquid viscosity. The criterion for deciding if the entrapped air evolves into single or double bubbles is rationalized, based on competition among inertia, capillarity, and viscosity. Additionally, it was found that low viscosity and low surface tension induce formation of a small daughter droplet encapsulated by an air shell, resulting in formation of an antibubble. A complete phase diagram for air evolution is demonstrated with respect to hydrodynamic conditions.

Experiments

We studied the impact of a liquid drop on a pool of the same liquid with X-ray imaging. To achieve high-intensity light source, white-beam X-ray with a peak irradiance of ~1014 ph/s/mm2/0.1% bw was used24,25. The detector system comprises a fast scintillator crystal (LuAG:Ce, decay time ~50 ns), a right-angle mirror and the microscope objective (Mitutoyo M Plan APO 10x, NA = 0.21). The images were captured with a CMOS high-speed camera (Photron Fastcam SA1.1). The imaging speed of the camera was synchronized to the X-ray beam using delay generators, enabling us to capture images with period of 3.68 μs and exposure time of 472 ns24,25. The drop-impact setup was installed 150 mm distance from the detector to achieve a strong phase-contrast effect. Liquid drops were dispensed from a syringe needle (26 G) connected with a remote-controlled syringe pump, resulting the droplet diameter to be 1.9 ~ 2.6 mm for different liquids. A laser beam was used to sense the drop and trigger the camera and the fast shutter that is installed before the sample stage. The liquid pool for the substrate was prepared in a cylinder made by Kapton film with a diameter ~20 mm and a depth ~50 mm, considered as a sufficiently deep pool19. The ambient temperature was carefully controlled to 20 °C in every experiment.

Results

X-ray imaging experiments

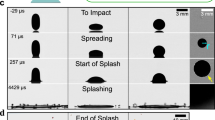

Wo used X-ray imaging experiments equipped with a drop-impact setup, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). The experiments were conducted at XSD 32-ID undulator beamline of the Advanced Photon Source in the Argonne National Laboratory. The air entrainment during drop impact on a liquid pool, as depicted in Fig. 1(b), was successfully taken as shown in Fig. 1(c). The imaging speed of the camera was synchronized to the X-ray beam using delay generators, enabling us to capture images with period of 3.68 μs and exposure time of 472 ns24,25,26. To investigate the effects of liquid viscosity (μ) and surface tension (γ), we tested two model systems: i) alkane oils (heptane (C7H16), dodecane (C12H26), and pentadecane (C15H32)) and ii) mixtures of water and glycerol (Wx-Gy) where x and y denote mass fractions; 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0. The liquid properties at temperature T = 293 K are summarized in Table 1, where all data were retrieved from the literature27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The diameters of liquid drops (D) were ~1.9 mm for oils and ~2.6 mm for W-G. The drop releasing heights (H) were controlled as 8 ~ 30 cm, corresponding to the impact velocities (U) as 1.25 ~ 2.4 m/s. The Weber number for the impacting drop was Wedrop = ρU2D/γ = 50 ~ 210, where ρ is the liquid density, and the Froude number for the impacting drop was Frdrop = U2/gD = 60 ~ 180, where g is the gravitational acceleration. Here the experimental conditions belong to an intermediate regime between bouncing and splashing35.

X-ray imaging setup and air bubble entrapment by drop impact on a liquid pool. (a) Schematic of X-ray imaging coupled with drop-impact setup. (b) Schematic of the bubble entrainment. When a liquid drop falls onto a liquid pool, a thin air film is entrapped and eventually contracts to one bubble or a few bubbles by surface energy minimization. (c) X-ray images corresponding to sketches in (b). The scale bar is 100 μm long.

Figure 2 representatively shows sequential X-ray images that demonstrate the evolution of the entrained air in drop impact on a liquid pool for alkane liquids with small γ (20 ~ 27 mN/m). The external shape as well as the exact internal morphology of the entrained air are clearly visualized in high spatial resolution (~2 μm). The evolution from initial air films to final bubbles seems very elegant but quite complicated to understand. For the pentadecane in Fig. 2(a) and Movie S1, the air film initially evolves into a pancake-shape, is stretched into a vertical column at 118 μs (note that this bubble does not touch the upper interface. The upper horizontal black line is because of the projection of the undisturbed front and back interfaces of the impacted region in X-ray penetration), and finally becomes one bubble at 177 μs. For the dodecane in Fig. 2(b) and Movie S2 with a lower viscosity, a longer vertical air column at 96 ~ 110 μs is formed and split into a double bubble (two bubbles) at 133 μs. For the heptane in Fig. 2(c) and Movie S3 with a much lower viscosity, the evolution becomes more complicated as follow. The central region of a pancake-like air film is punctured during retraction, forming a toroidal shape at 59 ~ 66 μs. The vertical stretching of the toroidal bubble at 66 ~ 81 μs induces the pinch-off of a daughter droplet at 81 ~ 88 μs, finally encapsulated by an air shell, forming an antibubble. The antibubble seems to have a similar configuration with a typical antibubble36,37, but the generation principle is quite different. Whereas the surfactant-stabilized antibubble is formed by oriented surfactant molecules that provide some elasticity to the air/liquid interfaces and ensure air-shell stability36,37, the origin of the the surfactant-free antibubble is the entrapped air by drop impact. These results clearly demonstrate that generation of single or double bubbles and antibubbles can be controlled during drop impact on a liquid pool by simply manipulating liquid viscosity.

X-ray images of air evolution for oils. (a) Impact of the pentedecane drop (μ = 2.8 mPa s) at H = 8 cm, indicating one bubble. (b) Impact of the dodecane drop (μ = 1.5 mPa s) at H = 8 cm, indicating a double bubble. (c) Impact of the heptane drop (μ = 0.4 mPa s) at H = 16 cm, indicating an antibubble. All individual images were taken with one X-ray pulse of 472 ns long. All the images were background-corrected. The time at impact moment was set to t = 0. The scale bar is 100 μm long.

For a water-glycerol mixture with large γ (62 ~ 72 mN/m), we observed a similar viscosity-dependent air evolution, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. During retraction, the air evolved into one bubble for the high-viscosity W0.4G0.6 as shown in Fig. 3(a) and Movie S4 but split into a double bubble (two bubbles) for the intermediate-viscosity W0.6G0.4 in Fig. 3(b) and Movie S5 as well as W0.8G0.2 in Fig. 3(c) and Movie S6. For the low-viscosity pure water, a daughter droplet was formed in Fig. 3(d) and Movie S7 but the toroidal bubble was eventually split at 96 ~ 111 μs into a double bubble. Here we note that the initial retracting discs show undulation (red arrows in Fig. 3) and tiny bubbles were formed in the later stages (yellow circles in Fig. 3).

X-ray images of air evolution for water-glycerol mixtures (W-G). Imaging condition is the same with Fig. 2. (a) Impact of a W0.4G0.6 drop (μ = 10.9 mPa s) at H = 12 cm. (b) Impact of a W0.6G0.4 drop (μ = 3.7 mPa s) at H = 12 cm. (c) Impact of a W0.8G0.2 drop (μ = 1.7 mPa s) at H = 12 cm. (d) Impact of a water drop (μ = 1.0 mPa s) at H = 12 cm. Here, one bubble in (a), a double bubble in (b–d), and additional tiny bubbles (yellow circles) were generated. The scale bar is 100 μm long.

Retraction dynamics

The retraction of the entrained air film in drop impact on a liquid pool has been studied mostly in inviscid liquids17. Here, we systematically investigated retraction dynamics in a wide range of liquids. The retraction dynamics of a thin fluid sheet is governed by the competition among inertia, capillarity, and viscosity38,39,40. Here, we describe the retraction of an air film. For simplicity, the air film is considered as a flat disc with a radius R and a thickness δ. For inviscid fluids, the retraction speed of the air disc determined by a balance between capillary and inertia can be approximated as dR/dt ≈ CiR/τi, where Ci is the inertial proportional coefficient and τi is the inertial relaxation time38,41 as defined as \({\tau }_{i}=\sqrt{\rho (4/3)\pi {R}_{B}^{3}/\gamma }\) with RB as the radius of the final spherical bubble. By a simple integration of the equation of retraction speed, we obtain an equation for inertial retraction40:

where R0 is the initial radius of the disc. For viscous fluids, the retraction speed determined by a balance between capillary and viscosity can be approximated as dR/dt ≈ CvR/τv, where Cv is the viscous proportional coefficient and τv is the viscous relaxation time38,41,42,43 as defined as τv = μRB/γ. Eventually, we obtain an equation for viscous retraction:

The ratio of the two timescales, \({\tau }_{i}/{\tau }_{v}=\sqrt{(4/3)\rho \gamma {R}_{B}}/\mu \), corresponds to the inverse Ohnesorge number (Oh−1): Oh \(=\mu /\sqrt{\rho \gamma {R}_{B}}\) represents the effect of viscosity over inertia and surface tension13.

We measured the radii of air films with time, taking from the maximum lengths of the entrained air films on the X-ray images, as plotted in Fig. 4(a). Importantly, the retraction rate R(t)/R0 follows the inertial exponential decay for liquids with Oh < 0.1. For liquids with Oh > 0.1, however, the retraction rate significantly deviates from the exponential decay. The best-fit values of the proportional coefficients Ci and Cv for each liquid are plotted in Fig. 4(b). At Oh < 0.1, we find that Ci is almost invariant (1.3 ~ 1.8) when Cv linearly increases with Oh, indicating the inertial retraction. In contrast, at Oh > 10, Cv saturates to ~0.5 when Ci is inversely proportional to Oh, indicating the viscous retraction. The comparable values of Ci and Cv at intermediate ranges (0.1 < Oh < 10) indicate that the inertia and the viscosity influence the retraction dynamics. From Eqs. (1) and (2), the specific condition for Ci = Cv (or τi = τv) is expected at Oh \(=\sqrt{4/3}\approx 1.15\), as consistent with Fig. 4(b).

Retraction dynamics of the entrapped air film. (a) The film radius R measured with time t for oils and W-G mixtures. Here R and t are rescaled with R0 and τi, respectively. The solid line is for the theoretical inertial retraction, \(R(t)/{R}_{0}=\exp (-{C}_{i}t/{\tau }_{i})\), with Ci taken as 238,40,41. (b) The best-fit values of the proportional coefficients of liquids, Ci (red closed squares for oils and red open squares for W-G) and Cv (blue closed circles for oils and blue open circles for W-G), plotted as a function of Oh. Red and blue dashed lines are averages of data points. Red solid lines: Ci ≈ 2 for Oh < 0.1 and Ci ≈ Oh−1 for Oh > 10. Blue solid lines: Cv ≈ Oh for Oh < 0.1 and Cv ≈ 0.5 for Oh > 10.

Interestingly, a slight difference in Ci for oils (Ci ~ 1.8) and aqueous solutions (Ci ~ 1.3) was found at the inertial regime (Oh < 0.1). This can be explained by the hydrodynamic instability by large surface tension as in aqueous liquids20. Necklace rims are formed in aqueous liquids in Fig. 3, while smooth rims are formed in alkane liquids in Fig. 2. The necklace rim is responsible for the formation of tiny bubbles (dashed circles in Fig. 3) attributed to the capillary instability along the rim17,20,43.

Phase diagram

The evolution of the entrained air is affected by the interaction among inertia, capillarity, and viscosity. As plotted in Fig. 5, we obtain a phase diagram for the final fate of the air as functions of the inverse Ohnesorge number Oh−1 and the Weber number for the air film as defined as Wefilm = ρν2δ/γ which is the ratio of kinetic energy (inertia) to surface tension, where the retraction velocity ν is taken from the measured retraction speed \(\max (-dR/dt)\)38. In fact, ρ and γ were controlled in Table 1 and ν and δ were measured experimentally in the X-ray imaging. Remarkably, there are three distinct types of air evolution. A simple retraction to one bubble is found at low Oh−1 and low Wefilm (blue region) and a split of one into two bubbles is found at low Oh−1 and high Wefilm (red region). At high Oh−1 (green region), a daughter droplet is robustly formed but all three cases of one and two bubbles, or a shell bubble are possible.

Phase diagram for the bubble evolution with respect to Wefilm and Oh−1. The shape of symbols is analogue to that in Fig. 4(a). Blue open symbols: the simple retraction into one bubble; red open symbols: the breakup into a double bubble; closed symbols: pinch-off of a daughter droplet; blue closed symbols: single or an antibubble; red closed symbols: a double bubble. Inset: Aspect ratio Lo of a bubble, measured as a function of Wefilm for liquids. The solid line is the best fitting of allometric scaling: y = αxβ.

The bubble breakup can be explained with respect to the competition among inertia, capillarity, and viscosity on the bubble columns vertically elongated caused by the inertia of retraction, as seen in Figs. 2 and 3. This inertia of retraction, or retraction speed, is proportional to the impact speed of liquid drop because the initial thickness of air film as well as the size of trapped air bubble become smaller with the impact speed12. Thus, as seen in the inset of Fig. 5, the aspect ratio Lo of the bubbles, measured at their maximum elongation (for example, at t = 96 μs in Fig. 2(c)), increases with the kinetic energy of impacting liquid drop as Lo ~ We\({}_{film}^{\beta }\), where the best-fit exponent β is measured as ~0.486 ± 0.037. We find that the breakup usually occurs at high aspect ratios larger than a critical value, \({L}_{o}^{* } \sim 3.1\) in our data. The critical aspect ratio for typical breakup of fluid columns increases with fluid viscosity44,45,46,47. Thus, it is conceivable that the breakup would be suppressed at high liquid viscosity, i.e. high Oh. Generally, \({L}_{o}^{* }\) for the breakup is predicted to be proportional to Oh1/2 based on linear instability theory45,46. From the relations of Lo ~ We\({}_{film}^{\beta }\) and \({L}_{o}^{* } \sim \) Oh1/2, the dependence of the critical We\({}_{film}^{* }\) on Oh can be rationalized as We\({}_{film}^{* }\) ~ Oh(1/2β). This explains the boundary between breakup and no breakup in the phase diagram (Fig. 5), which is well matched with experimental data.

The formation of daughter droplets at small Oh (< ~ 0.025) in the green region of Fig. 5 is because of the capillary waves on the air film, similar to the case of drop impact on solid surfaces13,48. At the moment of entrapment of the air disc by drop impact on surfaces, capillary waves are generated at the disc edge and travel into the center. As the waves converge, their amplitudes grow and cause the contact of liquids from upside and downside, forming the air film into a toroidal shape. Then pinch-off of a daughter droplet occurs inside the bubble. This process is well illustrated in Fig. 6(a). The capillary waves are balanced with the viscous dissipation: the critical Oh values are 0.026 or (Oh*)−1 = 38.46 for droplet pinch-off49 and 0.052 or (Oh*)−1 = 19.23 for bubble pinch-off 4. Therefore, the daughter droplet can be formed for low-viscosity liquids with Oh−1 > 40 (Oh < 0.025) in Fig. 5. Additionally, decreasing Oh at Oh < 0.03 would increase the daughter droplet size, as seen in the ratio of the daughter droplet volume (VD) to the bubble volume (VB) measured as a function of Oh in Fig. 6(b). The pinch-off driven formation of the daughter droplet at Oh−1 > 40 or Oh < 0.025 is consistent between the theory4,49 and the experiment in Figs. 5 and 6(b).

The interaction of a daughter droplet with the surrounding liquid plays a crucial role in determining the final fate of the bubble. For the heptane, the daughter droplet coalesces axisymmetrically with the surrounding liquid and splits the bubble into a double bubble (Fig. 7(a)) or does not coalesce and instead remains inside the shell bubble, forming an antibubble (Fig. 7(b)). In rare cases, the daughter droplet forms one-sided coalescence with the surrounding liquid, resulting in one bubble (Fig. 7(c)). For water, the daughter droplet forms total coalescence (Fig. 8(a)) or one-sided coalescence at the equator of the vertically elongated bubble (Fig. 8(b)). In some events, the daughter droplet can coalesce with the surrounding liquid at the bottom of the bubble, resulting in one bubble as well (Fig. 8(c)). The coalescence is a random process and may not always happen in the center41. For water, there was no event of shell bubble formation in our experiments.

Sequential X-ray images of evolution of the entrapped bubble for the heptane. (a) The axisymmetric coalescence of the daughter droplet and the surrounding liquid splits the bubble into a double bubble. (b) No coalescence results in an antibubble comprising the daughter droplet inside. (c) One-sided coalescence of the daughter droplet with the surrounding liquid results in one bubble. The scale bar is 100 μm long.

Sequential X-ray images of evolution of the entrapped bubble for water. (a) The axisymmetric coalescence forms the bubble split into two bubbles. (b) The one-sided coalescence results in one bubble. (c) The bottom-sided coalescence of the daughter droplet in a peanut-like bubble also results in one bubble. The scale bar is 100 μm long.

The frequency of all the cases of single, double, or anti- bubbles at various experimental conditions are plotted in Fig. 9(a). The radius of the final spherical bubble RB is the average radius of the final single, double, or anti- bubbles, taken from the final bubble images. In a view of typical hydrodynamics, the air layer between surrounding liquid and the daughter droplet becomes very thin (< 1 μm) after the pinch-off. Thus, the layer is easily broken in water because of its high disjoining pressure, resulting in the split of the bubble into two, as illustrated in Fig. 9(b). Conversely, the thin air layer is not easily broken in oil because of its small surface tension, thus playing as a lubricating layer between the daughter droplet and surrounding oil, as illustrated in Fig. 9(c). Additionally, hydrodynamic instability may induce one-sided coalescence of the daughter droplet, eventually forming one bubble, as illustrated in Fig. 9(d). One interesting point in Fig. 9(a) is that for water, the events of no-split for one bubble are more frequently observed at high impact heights. This can be explained by the decrease in the bubble size with impact height, as shown in the top panel of Fig. 9(a). The increase in Oh by the decreased bubble size results in the decrease of the daughter droplet size, reducing the coalescence probability.

The fate of entrapped air. (a) (bottom) Probability density of the final fate of the entrapped bubbles for water (left) and the heptane (right) at different impact heights. (top) Average radius of the bubbles of water (left) and the heptane (right) at different impact heights. Schematic illustrations for (b) bubble breakup by total coalescence (a double bubble), (c) shell bubble formation (an antibubble), and (d) one-sided coalescence (one bubble).

Discussion

The speed of impacting drop can significantly affect the initial dynamics of air. When the speed is low as U < 0.5 m/s, rupture occurs at numerous locations simultaneously, entrapping a multitude of tiny bubbles, known as the Mesler entrainment18,50. For U > 0.5 m/s, the air layer under the drop ruptures along an azimuthal ring and a disc-shaped air film is stably entrapped18,20. Especially, for U = 1.0 ~ 2.5 m/s, as applied here, the evolution dynamics of the air films is hardly affected by the impacting speed, except for their size dependency on the speed19, as fitted by RB ~ U−0.436 in Fig. 10. This relation estimates RB ~ 70 μm at U ~ 0.25 m/s, as consistent with the previous measurement of RB ~ 60μm51 for an ethanol droplet of 0.9 mm radius at U ~ 0.25 m/s.

Here, the Weber number of the impacting drop was markedly similar between this study for drop impact on liquid pools (Wedrop ~ 50–210) and previous studies for drop impact on solid substrates (55–7013 or 70–90048), but the below boundary condition was markedly different. This study clearly reveals the variety of air evolution dynamics. At very high impact speeds, collapsing of the impact crater would be a main mechanism for the bubble entrainment16, generally known as regular bubble entrainment. Also, unusual phenomena such as the cascade entrapment of bubble-rings21, and the formation of vortex streets also can occur52. By expanding the experimental conditions, one may be able to explore such singular hydrodynamic behavior in drop impact on liquid using novel techniques such as ultrafast X-ray phase-contrast imaging.

Finally, we did not consider the effect of variation of air properties such as air temperature and viscosity. The change in air temperature can modify the properties of liquid, in particular liquid viscosity (generally, the viscosity becomes smaller at a higher temperature), and thus can shift the boundaries between regions in the phase diagram. The change in air viscosity significantly affects the whole dynamics of drop impact53 and thus it would be crucial to investigate the effect of air viscosity on air entrapment during drop impact on a liquid pool. Further studies should be expanded to understand the oblique impact of droplets on deep liquid pools54,55,56, the impact of viscoelastic or viscous droplets57,58,59, and the impact-induced fabrication60,61, with more facilitating of numerical62, theoretical63, and experimental approaches64,65.

Conclusion

In summary, the novel ultrafast X-ray phase-contrast imaging is useful for us to explore the dynamics of the air entrainment during drop impact on a liquid pool. We elaborated two retraction mechanisms of the entrapped air film, inertial and viscous retractions, which strongly depend on the liquid viscosity. We found two crucial dynamic singularities after retraction: (i) the breakup of the bubble, mostly characterized with the bubble geometry and the liquid property, and (ii) the pinch-off of the daughter droplet (at Oh < 0.025) and its effect on the final fate of the bubble, which have been unachievable using conventional imaging techniques. Finally, predicting the morphological evolution of the entrained air would be assessable via the phase diagram with respect to hydrodynamic conditions.

References

Yarin, A. L. Drop impact dynamics: splashing, spreading, receding, bouncing. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 38, 159–192 (2006).

Wanninkhof, R., Asher, W. E., Ho, D. T., Sweeney, C. & McGillis, W. R. Advances in quantifying air-sea gas exchange and environmental forcing. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 213–244 (2009).

Woodcock, A. H., Kientzler, C. F., Arons, A. B. & Blanchard, D. C. Giant condensation nuclei from bursting bubbles. Nature 172, 1144–1145 (1953).

Lee, J. S. et al. Size limits the formation of liquid jets during bubble bursting. Nat. Commun. 2, 367 (2011).

Pumphrey, H. C. & Elmore, P. A. The entrainment of bubbles by drop impacts. J. Fluid Mech. 220, 539–567 (1990).

Prosperetti, A. & Oguz, H. N. The impact of drops on liquid surfaces and the underwater noise of rain. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 25, 577–602 (1993).

Dhir, V. K. Boiling heat transfer. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 39, 365–401 (1998).

Mehdi-Nejad, V., Mostaghimi, J. & Chandra, S. Air bubble entrapment under an impacting droplet. Phys. Fluids 15, 173–183 (2003).

Mandre, S., Mani, M. & Brenner, M. P. Precursors to splashing of liquid droplets on a solid surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 134502 (2009).

Mani, M., Mandre, S. & Brenner, M. P. Events before droplet splashing on a solid surface. J. Fluid Mech. 647, 163–185 (2010).

Hicks, P. D. & Purvis, R. Air cushioning and bubble entrapment in three dimensional droplet impacts. J. Fluid Mech. 649, 135–163 (2010).

Kolinski, J. M. et al. Skating on a film of air: drops impacting on a surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 074503 (2012).

Lee, J. S., Weon, B. M., Je, J. H. & Fezzaa, K. How does an air film evolve into a bubble during drop impact? Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 204501 (2012).

Liu, Y., Tan, P. & Xu, L. Compressible air entrapment in high-speed drop impacts on solid surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 716, R9 (2013).

Oguz, H. N. & Prosperetti, A. Bubble entrainment by the impact of drops on liquid surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 219, 143–179 (1990).

Deng, Q., Anilkumar, A. V. & Wang, T. G. The role of viscosity and surface tension in bubble entrapment during drop impact onto a deep liquid pool. J. Fluid Mech. 578, 119–138 (2007).

Thoroddsen, S. T., Etoh, T. G. & Takehara, K. Air entrapment under an impacting drop. J. Fluid Mech. 478, 125–134 (2003).

Thoroddsen, S. T., Thoraval, M. J., Takehara, K. & Etoh, T. G. Micro-bubble morphologies following drop impacts onto a pool surface. J. Fluid Mech. 708, 469–479 (2012).

Tran, T., de Maleprade, H., Sun, C. & Lohse, D. Air entrainment during impact of droplets on liquid surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 726, R3 (2013).

Thoraval, M. J. & Thoroddsen, S. T. Contraction of an air disk caught between two different liquids. Phys. Rev. E 88, 061001(R) (2013).

Thoraval, M. J., Takehara, K., Etoh, T. G. & Thoroddsen, S. T. Drop impact entrapment of bubble rings. J. Fluid Mech. 724, 234–258 (2013).

Wang, A. B., Kuan, C. C. & Tsai, P. H. Do we understand the bubble formation by a single drop impacting upon liquid surface? Phys. Fluids 25, 101702 (2013).

Hendrix, M. H. W., Bouwhuis, W., van der Meer, D., Lohse, D. & Snoeijer, J. H. Universal mechanism for air entrainment during liquid impact. J. Fluid Mech. 789, 708–725 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Ultrafast X-ray study of dense-liquid-jet flow dynamics using structure-tracking velocimetry. Nat. Phys. 4, 305–309 (2008).

Fezzaa, K. & Wang, Y. Ultrafast x-ray phase-contrast imaging of the initial coalescence phase of two water droplets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 104501 (2008).

Lee, J. S., Weon, B. M. & Je, J. H. X-ray phase-contrast imaging of dynamics of complex fluids. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 46, 494006 (2013).

Cheng, N. S. Formula for the viscosity of a glycerol-water mixture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47, 3285–3288 (2008).

Ernst, R. C., Watkins, C. H. & Ruwe, H. H. The physical properties of the ternary system ethyl alcohol-glycerin-water. J. Phys. Chem. 40, 627–635 (1936).

Queimada, A. J., Quinones-Cisneros, S. E., Marrucho, I. M., Coutinho, J. A. & Stenby, E. H. Viscosity and liquid density of asymmetric hydrocarbon mixtures. Int. J. Thermophys. 24, 1221–1239 (2003).

Ducoulombier, D. et al. Pressure (1–1000 bars) and temperature (20–100 °C) dependence of the viscosity of liquid hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. 90, 1692–1700 (1986).

Grigoryev, B. A., Nemzer, B. V., Kurumov, D. S. & Sengers, J. V. Surface tension of normal pentane, hexane, heptane, and octane. Int. J. Thermophys. 13, 453–464 (1992).

Aralaguppi, M. I., Jadar, C. V. & Aminabhavi, T. M. Density, refractive index, viscosity, and speed of sound in binary mixtures of cyclohexanone with hexane, heptane, octane, nonane, decane, dodecane, and 2,2,4-trimethylpentane. J. Chem. Eng. Data 44, 435–440 (1999).

Korosi, G. & Kovats, E. S. Density and surface tension of 83 organic liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data 26, 323–332 (1981).

Wu, J., Nhaesi, A. H. & Asfour, A. F. A. Viscosities of eight binary liquid n-alkane systems at 293.15 K and 298.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 44, 990–993 (1999).

Rein, M. The transitional regime between coalescing and splashing drops. J. Fluid Mech. 306, 145–165 (1996).

Dorbolo, S., Caps, H. & Vandewalle, N. Fluid instabilities in the birth and death of antibubbles. New J. Phys. 5, 161 (2003).

Vandewalle, N., Terwagne, D., Gilet, T., Caps, H. & Dorbolo, S. Antibubbles, liquid onions and bouncing droplets. J. Colloid Surf. A 344, 42–47 (2009).

Bartolo, D., Josserand, C. & Bonn, D. Retraction dynamics of aqueous drops upon impact on non-wetting surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 545, 329–338 (2005).

Eggers, J., Fontelos, M. A., Josserand, C. & Zaleski, S. Drop dynamics after impact on a solid wall: theory and simulations. Phys. Fluids 22, 062101 (2010).

Kooij, S. A. et al. Sprays from droplets impacting a mesh. J. Fluid Mech. 871, 489–509 (2019).

Aarts, D. G. A. L. et al. Hydrodynamics of droplet coalescence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 164503 (2005).

Debregeas, G., Martin, P. & Brochard-Wyart, F. Viscous bursting of suspended films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3886–3889 (1995).

Weiss, D. A. & Yarin, A. L. Single drop impact onto liquid films: neck distortion, jetting, tiny bubble entrainment, and crown formation. J. Fluid Mech. 385, 229–254 (1999).

Stone, H. A., Bentley, B. J. & Leal, L. G. An experimental study of transient effects in the breakup of viscous drops. J. Fluid Mech. 173, 131–158 (1986).

Eggers, J. Nonlinear dynamics and breakup of free-surface flows. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 865 (1997).

Dong, H., Carr, W. W. & Morris, J. F. An experimental study of drop-on-demand drop formation. Phys. Fluids 18, 072102 (2006).

Castrejon-Pita, A. A., Castrejón-Pita, J. R. & Hutchings, I. M. Breakup of liquid filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 074506 (2012).

Thoroddsen, S. T., Etoh, T. G., Takehara, K., Ootsuka, N. & Hatsuki, Y. The air bubble entrapped under a drop impacting on a solid surface. J. Fluid Mech. 545, 203–212 (2005).

Blanchette, F. & Bigioni, T. P. Partial coalescence of drops at liquid interfaces. Nat. Phys 2, 254–257 (2006).

Esmailizadeh, L. & Mesler, R. Bubble entrainment with drops. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 110, 561–574 (1986).

Bouwhuis, W. et al. Maximal air bubble entrainment at liquid-drop impact. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 264501 (2012).

Thoraval, M. J. et al. von Karman vortex street within an impacting drop. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 264506 (2012).

Zhang, L. V., Toole, J., Fezzaa, K. & Deegan, R. D. Splashing from drop impact into a deep pool: multiplicity of jets and the failure of conventional scaling. J. Fluid Mech. 703, 402–413 (2012).

Gielen, M. V. et al. Oblique drop impact onto a deep liquid pool. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 083602 (2017).

Guo, Y. & Lian, Y. High-speed oblique drop impact on thin liquid films. Phys. Fluids 29, 082108 (2017).

S. A. Reijers, B. Liu, D. Lohse, & H. Gelderblom Gelderblom, Oblique droplet impact onto a deep liquid pool. arXiv:1903.08978 (2019).

Jalaal, M., Kemper, D. & Lohse, D. Viscoplastic water entry. J. Fluid Mech. 864, 596–613 (2019).

Ray, B., Biswas, G. & Sharma, A. Regimes during liquid drop impact on a liquid pool. J. Fluid Mech. 768, 492–523 (2015).

Jain, U., Jalaal, M., Lohse, D. & van der Meer, D. Deep pool water-impacts of viscous oil droplets. Soft Matter 15, 4629 (2019).

Haldar, K. & Chakraborty, S. Effect of liquid pool concentration on chemically reactive drop impact gelation process. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 528, 156–165 (2018).

Wang, W., Ji, C., Lin, F., Wei, X. & Zou, J. Formation of water in oil in water particles by drop impact on an oil layer. Phys. Fluids 31, 037107 (2019).

Liang, G., Shen, S. & Mu, X. Numerical analysis and insight of drop impacting dynamics upon a liquid film. Acta Mechanica 228, 385–400 (2017).

Bouwhuis, W., Hendrix, M. H. W., van der Meer, D. & Snoeijer, J. H. Initial surface deformations during impact on a liquid pool. J. Fluid Mech. 771, 503–519 (2015).

Michon, G.-J., Josserand, C. & Séon, T. Jet dynamics post drop impact on a deep pool. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 023601 (2017).

Marcotte, F., Michon, G.-J., Séon, T. & Josserand, C. Ejecta, corolla, and splashes from drop impacts on viscous fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 014501 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (2006-0050683, NRF-2017R1E1A1A01075274, and 2019R1A6A1A03033215). Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.L., B.M.W. and J.H.J. designed the study. J.S.L. and S.J.P. conducted the main experiments. J.S.L. and B.M.W. collected the data and analyzed the results. J.T.K. and J.P. helped in the experiments. K.F. managed the X-ray imaging facility. J.H.J. supervised the study. J.S.L., B.M.W. and J.H.J. wrote the initial manuscript. B.M.W. and J.H.J. revised the final manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.S., Weon, B.M., Park, S.J. et al. Air evolution during drop impact on liquid pool. Sci Rep 10, 5790 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62705-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62705-5

This article is cited by

-

Spray cooling heat transfer enhancement by ethanol additive: Effect of Sauter mean diameter and fluid volumetric flux

Heat and Mass Transfer (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.