Abstract

The goal of this study was to explore diagnostic colonoscopy completion in adults with abnormal screening fecal immunochemical test (FIT) results. This was a secondary analysis of the Strategies and Opportunities to Stop Colon Cancer in Priority Populations (Stop CRC) study, a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial to increase uptake of CRC screening in federally qualified community health clinics. Diagnostic colonoscopy completion and reasons for non-completion were ascertained through a manual review of electronic health records, and completion was compared across a wide range of individual patient health and sociodemographic characteristics. Among 2,018 adults with an abnormal FIT result, 1066 (52.8%) completed a follow-up colonoscopy within 12 months. Completion was generally similar across a wide range of participant subpopulations; however, completion was higher for participants who were younger, Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, and had zero or one of the Charlson medical comorbidities, compared to their counterparts. Neighborhood-level predictors were not associated with diagnostic colonoscopy completion. Thus, completion of a diagnostic colonoscopy was relatively low in a large sample of community health clinic adults who had an abnormal screening FIT result. While completion was generally similar across a wide range of characteristics, younger, healthier, Hispanic participants tended to have a higher likelihood of completion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality have declined markedly among Americans ages 50 and older since 1990, a victory partially attributable to improved screening rates1. However, the burden of CRC has not been alleviated among those in the lowest socioeconomic groups2,3. Screening adherence has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of CRC incidence and death, consistent with the assumption that removing pre-cancerous adenomas prevents their progression to carcinoma4. And although CRC screening has increased to the point that those with the highest income meet the Healthy People 2020 goal of 70% screen-compliance, fewer than 40% of those who live below the poverty level are adequately screened5.

Annual fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a cost-effective screening strategy with relatively low patient burden6. Therefore, increasing the uptake of FIT testing in primary care and safety-net clinics has been the focus of several studies7,8,9. An essential corollary to FIT uptake is the delivery of timely follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy for individuals with a positive FIT result. This follow-up makes it possible to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer and prevent more advanced-stage disease; low follow-up colonoscopy completion substantially reduces the effectiveness of FIT screening10,11. In addition, lengthy intervals (e.g., >10 months) between the FIT positive result and follow-up colonoscopy can increase the risk of CRC or advanced-stage disease10. The proportion completing a follow-up colonoscopy after a FIT-positive result has been reported to be approximately 30% to 60% in safety-net and Veterans Affairs health care systems12,13,14,15,16, rising to ~80% in integrated health care organizations17,18. However, interventions, such as nurse navigators, have achieved up to 91% follow-up colonoscopy completion17,19. Clearly, health center systems and resources affect follow-up colonoscopy completion.

In addition to delivery-system-level variation, patient and clinician factors influence follow-up colonoscopy adherence. Patients and clinicians in low-resource clinical settings who comply with FIT screening face additional barriers to completing a timely follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy essential for cancer prevention. Low socioeconomic status (SES) and lack of continuity in care correspond to lower odds of completing follow-up colonoscopy20,21. Within safety-net health care settings, follow-up completion also differs by patient factors, such as race/ethnicity, sex, age, and comorbidities13,14,22, and system or clinician factors, such as referral and scheduling practices14.

In a pragmatic clinical trial of FIT mailing in federally qualified health centers, we have demonstrated increased FIT uptake9, with between 8% and 21% of individuals screening positive23. Given the importance of follow-up colonoscopy in realizing the benefits of improved FIT screening, we investigated individual and neighborhood factors associated with timely follow-up colonoscopy completion.

Methods

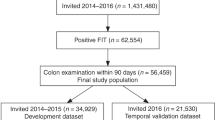

The Strategies and Opportunities to Stop Colon Cancer in Priority Populations (Stop CRC) study is a 26-clinic pragmatic cluster-randomized study of CRC screening in federally qualified community health centers (CHC) in Oregon and California, USA. Stop CRC was designed to test the use of a direct-mail approach to CRC screening as compared to usual care24. The Stop CRC intervention did not include active strategies to increase uptake of follow-up colonoscopies among those with a positive FIT result With few exceptions, Stop CRC clinics used one of three FIT brands: InSure (Enterix, Inc., Edison, NJ; positivity threshold 50 µg hHb/g feces), OC-Micro (Polymedco, Inc., Cortlandt Manor, NY; 20 µg hHb/g), and Hemosure (Hemosure, Inc., Irwindale, CA; 50 µg hHb/g). The current study is a prospective cohort analysis examining completion of follow-up colonoscopy among participants in both the intervention and control groups who had abnormal FIT results.

The Institutional Review Board of Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW IRB) approved all study activities, and participating clinics ceded human subjects review authority to the KPNW IRB. We obtained a waiver of informed consent from the KPNW IRB. Primary outcomes of the Stop CRC trial have been reported9.

Participant eligibility

Within each CHC included in Stop CRC, individuals were eligible if they were (1) 50–74 years old, (2) had attended a clinic visit in the previous year, and (3) were due for CRC screening. Being due for screening was defined as having no evidence in the electronic health record (EHR) of either (1) a fecal test in the previous year, (2) an order for a fecal test in the previous 6 months, (3) a flexible sigmoidoscopy in the previous 4 years, (4) a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years, or (5) an order for a sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy in the previous year. Individuals were excluded if they had EHR evidence of several health conditions that made them poor candidates for fecal testing (e.g., a history of CRC, colon disease, or renal failure)25.

Analytic sample

The current study is limited to the 2,018 participants who returned a FIT and had an abnormal FIT result between February 4, 2014, and August 3, 2016.

Data sources

All data were extracted from EHRs, accessed in collaboration with the Oregon Community Health Information Network (OCHIN). OCHIN is a non-profit health center network with an organization wide EHR that allows researchers to access sociodemographic, clinical, and utilization data across all OCHIN clinic sites. Neighborhood variables were obtained from the ADVANCE Clinical Data Research Network26, based on the participant’s address on February 4, 2014, or the closest record to that date.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a completed colonoscopy within 12 months of the participant’s first positive FIT result. The EHR of every person with an abnormal FIT was manually examined for evidence of a completed colonoscopy. We relied on manual chart abstraction for this outcome rather than electronic clinical databases because colonoscopy services were typically referred to clinics outside the OCHIN network, and in those cases colonoscopy results may have been manually entered into the health record without using the standard procedure code fields that are exported to searchable databases.

In addition, the EHR was examined for notation related to the reason a follow-up colonoscopy was not completed. Reasons were coded into the following categories: the individual declined, had a recent colonoscopy, could not be found and notified, did not come to their scheduled colonoscopy appointment, the clinician considered the individual to be a poor candidate for a colonoscopy, the individual was given a second FIT to confirm the abnormal result before scheduling a colonoscopy, and inadequate or intolerance to prep for the colonoscopy.

Predictors of service use

Individual characteristics

Individual characteristics, including demographics, insurance status, income relative to federal poverty level, and office visits in the year prior to initial eligibility determination, were ascertained through OCHIN EHR. Health conditions in the year prior to eligibility were determined by calculating the Charlson comorbidity index, using the Elixhauser coding algorithms27. EHR evidence of screening behaviors — Pap within the previous 3 years, mammogram within the previous 2 years, and flu shot within the previous year — were also collected.

Neighborhood characteristics

Most neighborhood characteristics were collected at the census tract level, and included Gini Index (a measure of income inequality)28, unemployment rate, population density, median household income, percent of college graduates, and the percentage of residents who are at or below the poverty level. The variable for rate of Emergency Department visits per 1000 Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) enrollees was collected at the county level. Neighborhood characteristics were defined based on the participant’s address at the time of enrollment, which was linked via geocoding to variables from the American Community Survey census data29 and the CMS Geographic Variation database30. These neighborhood-level variables were dichotomized based on associated statistics in the United States, as close to the year 2014 as possible for consistency with the timeline of the study (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Simple frequency tables were constructed to examine the reasons for non-completion of a follow-up colonoscopy and to describe the demographic, socioeconomic, health-related, and neighborhood-level predictors. To examine factors that influenced the likelihood of completing a follow-up colonoscopy, relative risks were calculated using log-linked binomial models, with the dichotomous outcome indicating follow-up colonoscopy completion, and the model included one predictor at a time, controlling for age, sex, and health system. PROC GENMOD in SAS version 9.4 was used for this analysis. Most predictors were dichotomous (e.g., presence or absence of a medical condition) or categorical in nature, and others were dichotomized according to a clinically or otherwise meaningful logic, such as BMI at the standard cut-off for obesity. Predictors that had 20 or fewer participants for either level of the variable were not included in further analyses. All significance testing was 2-tailed, and results were considered statistically significant if the p-value was 0.05 or less.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Overall, 2,018 (17.7%) of 11,427 participants who completed a FIT had an abnormal FIT result. Of these, 1,066 (52.8%) completed a follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy within 12 months of their FIT test. The proportion completing a FIT ranged from 47.2% to 60.9% (data not shown) across health systems, highlighting the importance of controlling for health system in subsequent analyses. The median time to completion was 72 days (interquartile range, 49 to 120).

Reasons for noncompletion were found in the EHR of 546 of the 952 participants who did not complete a follow-up colonoscopy (Table 2). The most common reason for non-completion was that the patient declined, noted for 237 (43.4%) of the 546 participants with a reason recorded. Twenty-two percent had a recent colonoscopy, 12.5% could not be found for notification, and 10.3% did not show up to a scheduled appointment. When the participants who declined the follow-up colonoscopy due to self-report of a recent colonoscopy were removed from the denominator, completion increased slightly, to 56.2% (1066/1897).

Across a wide range of potential predictor categories, follow-up colonoscopy completion fell between 45% and 55% for most participant subgroups. The percent completing a follow-up colonoscopy for demographic and socioeconomic subgroups and the between-group effects are shown in Table 3. Follow-up colonoscopy completion was lower for adults age 65–74 (45.3%) than those aged 50–64 (54.7%, adjusted RR [aRR] = 0.84, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.94), and the highest completion was seen for participants who were Hispanic (63.1%, vs. 52.0% non-Hispanic, aRR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.36) and Spanish-speaking (67.0%, vs. 52.2% and 51.0% for English and other languages, respectively, aRR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.50 relative to English speakers). Participants with a Charlson comorbidity index of 2 or more were less likely to complete a follow-up colonoscopy (47.4%) than those with an index value of zero or one (54.5%, aRR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.98, Table 4). The only specific health condition that was statistically significantly associated completion of a follow-up colonoscopy was renal disease; 39.1% of participants with a diagnosis of renal disease completed a follow-up colonoscopy, compared with 53.4% of those without (aRR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.97). None of the neighborhood-level predictors were associated with completion of a follow-up colonoscopy (Table 5).

Discussion

In this pragmatic trial of FIT screening, 52.8% of participants who had an abnormal FIT completed a follow-up colonoscopy within one year. This finding is consistent with other studies in safety-net health clinics, which have found 52% to 58% of individuals completing follow-up colonoscopies at sites in Chicago22, Texas14, and San Francisco13. Follow-up colonoscopy completion is alarmingly low; given the positive predictive value of the FIT tests used in this study for identifying advanced adenoma or cancer (range 0.17 to 0.3023), an expected 161 to 286 individuals in the Stop CRC cohort of 11,427 participants are at unnecessary risk of disease progression and cancer mortality.

Completion was generally consistent across a wide range of potential sociodemographic, health, and neighborhood-level predictors, including income and insurance status, which may be hypothesized to have an important influence on completion among this economically disadvantaged population. Hispanic and Spanish-speaking participants had higher than average completion of follow-up colonoscopy, however. Interestingly, in a pilot study of one health center in the Stop CRC study examining colonoscopy completion among individuals with an abnormal FIT (n = 56 with an abnormal FIT), we reported that Hispanics and women had markedly lower odds of completing follow-up colonoscopy within 18 months than non-Hispanic whites and men31. In that analysis of a clinic predominantly serving Hispanic individuals, 45% of Hispanics and 70% of non-Hispanic those with a positive FIT received follow-up colonoscopy. It is unclear why results differed so markedly between the pilot and full study, but the fact that colonoscopy completion varied substantially between the pilot and full study hints at the possibility of between-clinic variability in patterns of follow-up colonoscopy. In contrast, another trial found essentially no ethnic difference (70% among Hispanics and 68% among non-Hispanic whites) in the geographically diverse clinics participating in the Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium32. Interestingly, one other study did report an increased likelihood of follow-up colonoscopy among Spanish-speaking individuals in community health centers in Chicago (RR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.36, compared with English-speaking individuals)22.

We found a lower likelihood of follow-up colonoscopy among older (age 65 or more) adults. Other studies have also found similar associations13,14,33, among adults in the age range covered by the USPSTF screening recommendation. For example, a study of a PROSPR consortium CHC clinics in Texas (n = 1,267) found an OR of 1.59 (95% CI 1.15 to 2.17) comparing those aged 61–64 vs. 50–5514. However, other studies have found no age differences in follow-up colonoscopy completion12,18,34.

We also found a lower likelihood of follow-up colonoscopy completion among those with a Charlson index of two or more and in those with renal disease. Similarly, in several other studies individuals who lacked follow-up colonoscopy had more comorbidities14,20. For example, individuals in the PROSPR consortium clinics with a Charlson comorbidity index score ≥3 were less likely to complete a colonoscopy than those with a score of 0 (HR = 0.70)35.

Given the overall low completion of follow-up colonoscopy, effective strategies to increase the likelihood of completion are needed. Several intervention efforts have focused on improving clinician and system factors affecting follow-up colonoscopy referral and scheduling. A recent systematic review found improved colonoscopy completion with the use of personalized letters signed by the participant’s primary care clinician, notification of results by phone, phone reminders to complete a colonoscopy, and the use of patient navigators36. Provider-level interventions that sent reminders or performance data to clinicians were also generally associated with increased rates of follow-up colonoscopy completion36. In addition, the same review identified several system-level intervention studies that demonstrated increased completion rates over usual care, including an automated referral to a gastroenterologist, replacing a pre-colonoscopy visit with a phone call, creating a registry to track individuals with an abnormal FIT, and multi-component quality improvement interventions. These and other strategies should be more widely implemented, and may be particularly important for older adults and those with multiple medical conditions, who had lower completion rates in this study when there were no specific activities to encourage the completion of follow-up colonoscopies.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis has several important limitations. This was an exploratory study which examined the impact of many predictors, making it likely that some statistically significant findings were chance occurrences. However, many of our findings replicated those found previously (e.g. age, presence of multiple comorbidities), improving our confidence in the stability of these findings. Nevertheless, the prior evidence base for some predictors are mixed (e.g., Hispanic individuals) and some predictors lacked prior support (e.g., patients with renal disease). Another limitation is that reasons for non-completion was often missing or was non-specific (e.g., “patient declined”). Colonoscopies were typically referred to external clinicians, so getting results and reasons for non-completion into the participant’s EHR required the successful interface across health entities, leaving room for error. The fact that 121 individuals reported that they had a recent colonoscopy, among those with reasons for non-completion, suggests that some colonoscopy reports were not returned to the individual’s primary medical record. Another limitation was the small numbers of patients with some of the health conditions of interest. Frequently, there were fewer than 100 participants with a target health condition, limiting our confidence in these results and the power to detect differences. A fourth limitation is that our sample had very limited racial/ethnic diversity, with 83% identifying as white and 93% as non-Hispanic. The small absolute numbers of non-white and Hispanic participants reduce our confidence in the generalizability of those results to other CHC settings. In addition, the fact that most participants were from low socioeconomic group limits generalizability to more economically advantaged populations.

Finally, another limitation to our study is that there were a large number of site that conducted colonoscopies, but we did not gather information on colonoscopy site such as location or standard procedures (e.g., requirements for pre-visits, escorts, and transportation) that may affect follow-up colonoscopy completion rates. Colonoscopies were typically referred to specialists outside of the primary care clinic. Chart review was conducted at the primary care clinic, and the findings were limited to procedure reports, pathology reports and physician notes. However, we attempted to mitigate both the impact of the variability in how the colonoscopy sites interacted with the health systems and differences in procedures in the health systems by controlling for health system in our analysis.

A strength of our study was that we conducted a manual health record review, which looked beyond procedure or diagnosis codes in standard fields to include images, scanned documents, and other information noted in free text fields. Capture of outcomes was further enhanced by the nature of the OCHIN consortium, which ensures that patients have a single OCHIN medical record that captures utilization and medical information from any OCHIN-affiliated health system. In addition, the richness of the socioeconomic data is a strength of this study. In addition to the geocoded-neighborhood level data, the OCHIN clinics routinely collect individual-level income data, when is then categorized in terms of the federal poverty level.

Conclusions

In this study set in 26 federally qualified CHCs, only 52.8% of individuals with an abnormal FIT result completed a follow-up colonoscopy within 12 months of the FIT result. The likelihood of completion was generally consistent across a wide range of potential predictors; however, Hispanic and Spanish-speaking individuals showed higher completion, while lower completion was found for those who were older than 65 years, had two or more medical conditions, or had renal disease. Patient refusal was the most commonly cited reason for non-completion. CHCs should consider implementing strategies to increase completion of follow-up colonoscopies after a positive FIT, particularly in older adults and those with multiple existing medical conditions.

References

Siegel, R. L. et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA. Cancer. J. Clin. 67, 177–193, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21395 (2017).

Breen, N., Lewis, D. R., Gibson, J. T., Yu, M. & Harper, S. Assessing disparities in colorectal cancer mortality by socioeconomic status using new tools: Health disparities calculator and socioeconomic quintiles. Cancer Causes Control 28, 117–125, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0842-2 (2017).

Teng, A. M., Atkinson, J., Disney, G., Wilson, N. & Blakely, T. Changing socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: Cohort study with 54 million person-years follow-up 1981–2011. Int. J. Cancer 140, 1306–1316, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30555 (2017).

Shaukat, A. et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 369, 1106–1114, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1300720 (2013).

Huang, D. T. QuickStats: Percentage of adults aged 50–75 years who received colorectal cancer screening*, by family income level† — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6146a10.htm?s_cid=mm6146a10_w (2012).

Knudsen, A. B. et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: Modeling study for the us preventive services task force. JAMA 315, 2595–2609, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.6828 (2016).

Gupta, S. et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 173, 1725–1732, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9294 (2013).

Goldman, S. N. et al. Comparative effectiveness of multifaceted outreach to initiate colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 30, 1178–1184, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3234-5 (2015).

Coronado, G. D. et al. Effectiveness of a mailed colorectal cancer screening outreach program in community health clinics: The STOP CRC cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Internal Medicine 178, 1174–1181, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3629 (2018).

Corley, D. A. et al. Association between time to colonoscopy after a positive fecal test result and risk of colorectal cancer and cancer stage at diagnosis. JAMA 317, 1631–1641, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3634 (2017).

Meester, R. G. et al. Consequences of increasing time to colonoscopy examination after positive result from fecal colorectal cancer screening test. Clin. Gastroentero.l Hepatol. 14, 1445–1451.e1448, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.017 (2016).

Fisher, D. A., Jeffreys, A., Coffman, C. J. & Fasanella, K. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1232–1235, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-05-0916 (2006).

Issaka, R. B. et al. Inadequate utilization of diagnostic colonoscopy following abnormal fit results in an integrated safety-net system. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 112, 375–382, https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.555 (2017).

Martin, J. et al. Reasons for lack of diagnostic colonoscopy after positive result on fecal immunochemical test in a safety-net health system. Am. J. Med. 130, 93.e91–93.e97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07.028 (2017).

Partin, M. R. et al. Organizational predictors of colonoscopy follow-up for positive fecal occult blood test results: An observational study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 24, 422–434, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-14-1170 (2015).

Powell, A. A., Nugent, S., Ordin, D. L., Noorbaloochi, S. & Partin, M. R. Evaluation of a VHA collaborative to improve follow-up after a positive colorectal cancer screening test. Medical Care 49, 897–903, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182204944 (2011).

Green, B. B. et al. Results of nurse navigator follow-up after positive colorectal cancer screening test: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 27, 789–795, https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.06.140125 (2014).

Miglioretti, D. L. et al. Improvement in the diagnostic evaluation of a positive fecal occult blood test in an integrated health care organization. Med. Care 46, S91–96, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817946c8 (2008).

Cha, J. M., Lee, J. I., Joo, K. R., Shin, H. P. & Park, J. J. Telephone reminder call in addition to mailing notification improved the acceptance rate of colonoscopy in patients with a positive fecal immunochemical test. Digestive Diseases &. Sciences 56, 3137–3142, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1720-0 (2011).

Correia, A. et al. Lack of follow-up colonoscopy after positive FOBT in an organized colorectal cancer screening program is associated with modifiable health care practices. Preventive Medicine 76, 115–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.028 (2015).

Morris, S. et al. Socioeconomic variation in uptake of colonoscopy following a positive faecal occult blood test result: A retrospective analysis of the NHS bowel cancer screening programme. British Journal of Cancer 107, 765–771, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.303 (2012).

Liss, D. T. et al. Diagnostic colonoscopy following a positive fecal occult blood test in community health center patients. Cancer Causes Control 27, 881–887, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0763-0 (2016).

Nielson, C. M. et al. Positive predictive values of fecal immunochemical tests used in the STOP CRC pragmatic trial. Cancer Med. 7, 4781–4790, https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1727 (2018).

Coronado, G. D. et al. Strategies and opportunities to STOP colon cancer in priority populations: Design of a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 38, 344–349, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.06.006 (2014).

Petrik, A. F. et al. The validation of electronic health records in accurately identifying patients eligible for colorectal cancer screening in safety net clinics. Fam Pract 33, 639–643, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw065 (2016).

DeVoe, J. E. et al. The ADVANCE network: Accelerating data value across a national community health center network. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 21, 591–595, https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002744 (2014).

Quan, H. et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care 43, 1130–1139, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 (2005).

United States Census Bureau. Census.gov glossary, https://www.census.gov/glossary.

United States Census Bureau. American community survey (ACS), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare geographic variation, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Geographic-Variation/index.html (2019).

Oluloro, A. et al. Timeliness of colonoscopy after abnormal fecal test results in a safety net practice. Journal of Community Health 41, 864–870, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0165-y (2016).

McCarthy, A. M. et al. Follow-up of abnormal breast and colorectal cancer screening by race/ethnicity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 51, 507–512, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.017 (2016).

Rao, S. K., Schilling, T. F. & Sequist, T. D. Challenges in the management of positive fecal occult blood tests. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24, 356–360, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0893-5 (2009).

Carlson, C. M. et al. Lack of follow-up after fecal occult blood testing in older adults: Inappropriate screening or failure to follow up? Archives of Internal Medicine 171, 249–256, https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.372 (2011).

Chubak, J. et al. Time to Colonoscopy after positive fecal blood test in four U.S. health care systems. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 25, 344–350, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0470 (2016).

Selby, K. et al. Interventions to improve follow-up of positive results on fecal blood tests: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine 167, 565–575, https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-1361 (2017).

World Bank Group. GINI index (World Bank estimate), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=US.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases, tables & calculators by subject, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Population with tertiary education (indicator), https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.htm#indicator-chart (2018).

US Census Bureau. Income and earnings summary measures by selected characteristics: 2013 and 2014, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/252/Table 1.pdf (2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergency department visits, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm (2017).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory program (UH2AT007782/4UH3CA18864002). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. This paper has not been presented previously.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.O. planned the analysis and drafted the results and discussion sections of the manuscript. C.N. drafted the introduction and methods sections of the manuscript. A.P. participated in the design of the pragmatic trial and led the implementation of the trial. B.G. participated in the design, obtaining funding and interpretation of results, writing, and editing of the manuscript. G.C. was the principle investigator of the pragmatic trial and responsible for the design, obtaining funding, the execution of the trial, interpretation of results, writing, and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Connor, E.A., Nielson, C.M., Petrik, A.F. et al. Prospective Cohort study of Predictors of Follow-Up Diagnostic Colonoscopy from a Pragmatic Trial of FIT Screening. Sci Rep 10, 2441 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59032-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59032-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.