Abstract

In this work, few-layered molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) was functionalized with metal oxide (MxOy) nanoparticles which served as a catalyst for carbon nanotubes (CNT) growth in the chemical vapour deposition (CVD) process. The resulting MoS2/MxOy/CNT functionalized nanomaterials were used for flame retarding application in poly(lactic acid) (PLA). The composites were extruded with a twin-screw extruder with different wt% loading of the nanomaterial. Full morphology characterization was performed, as well as detailed analysis of fire performance of the obtained composites in relation to pristine PLA and PLA containing an addition of the composites. The samples containing the addition of MoS2/MxOy/CNT displayed up to over 90% decrease in carbon oxide (CO) emission during pyrolysis in respect to pristine PLA. Microscale combustion calorimetry testing revealed reduction of key parameters in comparison to pristine PLA. Laser flash analysis revealed an increase in thermal conductivity of composite samples reaching up to 65% over pristine PLA. These results prove that few-layered 2D nanomaterials such as MoS2 functionalized with CNT can be effectively used as flame retardance of PLA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Greater use of conventional petroleum based commodity resins in various applications have led to inevitable rise of its ecological footprint. Various new eco-friendly biodegradable polymers were developed in order to counteract this effect. With its biodegradability, low emission of greenhouse gas and low production energy PLA currently stands as one of popular alternatives for conventional polymer materials1. Due to its high degree of transparency, good mechanical properties, low toxicity and ability to process using equipment as well as relatively low cost and large production volume it shows high potential for packaging, household and biomedical applications. Nevertheless, other potential applications such as in electronics or automotive industry require PLA grades with high impact strength, better processing ability and improved flame retardant behaviour2. In order to meet that demand novel methods of modification need to be developed and applied.

A common way of improving flame retardancy of polymer is through combining its matrix with flame retardant filler. In the past improved flame resistance was achieved by introduction of halogenated flame retardants (HFR). Nowadays, it faces severe restrictions in Europe and North America due to the release of toxic substances and large amounts of smoke during combustion3. Instead, halogen-free flame retardant formulations function more commonly now as an environmentally friendly alternatives for HFR. These include intumescent flame retardants4,5, phosphorus- and nitrogen-containing micro- and nanoparticles6,7,8, inorganic substances and silica derivatives9 which can be used either individually or in combination10 to achieve optimal flame retardant performance.

Polymer/layered inorganic materials composites have high potential for improving thermal properties of polymers. Molybdenum disulfide is a member of a family of transition metal dichalcogenides (TDM). Structurally its crystals are characterized as hexagonal layered configurations. Atoms in the layer are bonded with strong covalent bonding, while layers are packed together to form a sandwich structure with weak Van der Waals forces similarly to graphite or boron nitride11. With their unique electrical, optical, thermal and mechanical properties MoS2 nanosheets can be potentially used for application as fillers for improving properties of polymers. Being a representative of layered inorganic materials MoS2 is expected to disperse and exfoliate in polymers, which results in the physical barrier effects that inhibits the diffusion of heat and gaseous decomposition products12,13. Molybdenum, a transition metal element, promotes the formation of charred layer during the combustion which acts as a physical barrier that slows down the heat and mass transfer11. In order to achieve high-performance homogenous dispersion of MoS2 nanosheets in the polymer hosts and proper interfacial interactions need to be established14. Similarly to metal oxide/graphene hybrid materials addition of metal oxide/MoS2 nanoparticles might prevent the aggregation of MoS2 flakes during preparation of polymer nanocomposites and result in improved flame retardant performance15,16. In addition they can also lead to improved char generation due to catalytic activity of metal oxide as well as suppressed smoke production and reduced toxicity due to catalytic conversion of carbon oxide (CO)17.

Another possible alternative to the use of conventional flame retardants are carbon nanotubes (CNT). These can be introduced into the polymer matrix in pristine form of a small diameter (1–2 nm) single-walled carbon nanotubes or a large diameter (10–100 nm) multi-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT and MWCNT, respectively)18,19,20,21,22,23. In addition to this functionalization of CNT can also be carried out in order to significantly improve the flame retardant performance17. This can be performed in three different ways. Surface modification by coupling agents allows for enhancement of dispersion state of CNT24,25,26. For example, addition of 9 wt% content of CNT functionalized with vinyltriethoxysilane into epoxy composite allowed for increase of limiting oxygen index (LOI) from 22 to 27% and improvement of UL-94 rating from V-1 to V-025. This also resulted in increase of char yield at 750 °C by 46.94%. Char yield can be also enhanced through covalent linkage of organic flame retardants to CNT27,28,29,30 following surface treatment. Functionalization of CNT can facilitate their dispersion within the polymer matrix and enhance interfacial adhesion between the CNT and the polymer30. Formation of genuine composites can be confirmed by an increase in the Young’s modulus and flame resistance of compositions containing pristine CNT28. Finally, hybridization of CNT by inorganic particles can allow for superior flame retardant properties31,32,33. In addition to that other key parameters, such as thermal stability and dielectric properties, can be also enhanced31. Generally speaking, flame retardant actions of CNT/polymer composites involve the condensed phase action. Char layer formed on the entire sample surface acts as insulation layer that reduces the amount of volatiles escaping to the flame. The formation of continuous layer is obtained by formation of three-dimensional network structure when the content of CNT reaches a threshold value17. Good quality char plays major role in reduction of peak heat release rate (pHRR)34,35.

During the scope of presented research few-layered MoS2 nanosheets functionalized with MxOy nanoparticles served as catalysts for growth of CNT in the CVD process were prepared. The obtained nanomaterials were used as flame retarding agents in PLA composites. Detailed description of synthesis, as well as full characteristics and analysis of properties of obtained PLA-based composites were provided. Additionally, a thorough analysis of thermal stability, fire performance and thermal conductivity of these materials was also performed and discussed in details.

Methods

Materials

Bulk MoS2 (powder), N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) (anhydrous, 99.5%), cobalt(II) acetate tetrahydrate (99%), iron(II) acetate (95%) and nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate (98%) were purchased from Merck. PLA was obtained from Goodfellow. Hydrogen peroxide (30%) and ethanol (96%) were purchased from Chempur. Gaseous nitrogen and ethylene were purchased from Messer and Air Liquide, respectively.

Preparation of few-layered MoS2

1 g of bulk MoS2 powder was transferred into a 250 mL flat-bottomed beaker filled with solution of 95 mL of NMP and 5 mL of hydrogen peroxide. This was followed by 30 minutes of continuous sonication in an ultrasonic washer, after which solution was transferred to a 250 mL round bottomed flask, plugged to reflux and consciously stirred at 360 rpm and 35 °C for 24 h. Final dispersion was centrifuged four times at 10000 rpm for 20 minutes and washed with ethanol.

Preparation of MoS2/MxOy/CNT

In order to obtain MoS2/MxOy/CNT modified nanomaterials following procedure was applied. First, 150 mg of few-layered MoS2 and 150 mg of respective source of metal oxide (cobalt(II) acetate tetrahydrate, iron(II) acetate or nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate) were dispersed in ethanol and sonicated in an ultrasonic washer for 2 h. Next, dispersions were stirred for 48 h, after which they were dried under high vacuum at 440 °C for 3 h. This resulted respectively in MoS2/Co2O3, MoS2/Fe2O3 and MoS2/Ni2O3 modified nanomaterials. Next CVD was performed in tube furnace under constant 100 mLmin−1 flow of nitrogen at 850 °C with a 15 minute long, 60 mLmin−1 flow of ethylene as a source of carbon.

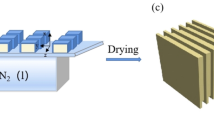

Extrusion of MoS2/MxOy/CNT modified PLA composites

PLA was utilized as a polymer matrix. Four composites were prepared, containing addition of few-layered MoS2, MoS2/Co2O3/CNT, MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT or MoS2/Ni2O3/CNT, respectively. For each composite three samples containing different amounts of nanomaterials additives were prepared − 0.5 wt%, 1 wt% and 2 wt%, respectively. Following 12 h of drying the nanomaterial ware blended with PLA using twin-screw extruder (Zamak Mercator EHP 2 × 12). For reference a sample of pristine PLA was also extruded.

Characterization

Morphology of nanomaterials obtained during each stage was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Tecnai F20, FEI) with 200 kV accelerating voltage. Raman analysis was performed in microscope mode (InVia, Renishaw) with a 785 nm laser in ambient air. Number of layers in few-layered MoS2 samples was determined using atomic force microscopy (AFM) (MultiMode 8, Bruker).

For the obtained composites and pristine PLA following analyses were performed. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using thermal analyzer (SDT Q600, TA Instruments) under airflow of 100 mLmin−1. In each case individual sample (ca. 5 mg in an alumina crucible) was heated from room temperature to 800 °C at a linear heating rate of 10 °Cmin−1. In addition to this, gaseous products from the heating process were analyzed in situ with a mass spectrometer (ThermoStar, Pfeiffer Vacuum) coupled with the TGA, under 100 mLmin−1 argon flow. Microscale combustion calorimetry (MCC) was employed for measurement of flame retardancy using FAA Micro Calorimeter, from FTT. This allowed for determination of pHHR, heat release capacity (HRC) and total heat release (THR) from 2 mg specimens. Thermal conductivity of the obtained samples was measured using laser flash apparatus (XFA 300, Linseis). Prior to this measurement the samples were spray coated with thin layer of graphite in order to facilitate the absorption of laser at the surface.

Results and Discussion

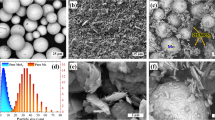

Successful preparation of few-layered MoS2 samples was confirmed using TEM and AFM (Fig. 1). Number of MoS2 layers was determined through analysis of high profile with AFM (Fig. 1C). The flakes were typically 5 nm in height, which corresponded to approximately 7 layers of MoS2 (assuming average thickness of single layer ca. 0.7 nm36 (Dependence between lateral size and aspect ratio in Supplementary information)). This was verified later with Raman spectroscopy as the intensity of \({E}_{2g}^{1}\) and \({A}_{1g}\) peaks changes between bulk MoS2 and few-layered MoS2. With the increased number of layers the frequency of \({E}_{2g}^{1}\) (~382 cm−1 for bulk MoS2) decreases while that of the \({A}_{1g}\) (~407 cm−1 for bulk MoS2) increases. This effect is caused by the interlayer van der Waals force in MoS2 suppressing the atom vibration, which results in higher force constants36,37.

Dispersion of metal oxide nanoparticles on the surface of MoS2 was determined from collected high-resolution TEM images presented in Fig. 2. Metal oxide nanoparticles appeared to be well dispersed on the surface and deposited homogenously. The nanoparticles size was measured and ranged between 5 and 25 nm for all metal oxide nanoparticles. Presence of CNT on samples from the CVD process was confirmed with TEM (Fig. 3). As observed, internal diameter of nanotubes matched the diameter of specific metal oxide nanoparticles. Hallow core and an open end were visible and the surface appeared to be smooth.

Thermal stability

TGA measurements were performed in order to study the influence of MoS2 as well as MoS2/MxOy/CNT nanomaterial on the thermal stability of PLA. Figure 4 presents the TGA curves for PLA/MoS2 and MoS2/MxOy/CNT composites in comparison to pristine PLA. Based on accumulated data T10wt%, T50wt% and Tmax values (which represent temperatures at which 10%, 50% and maximum weight loss occur) were registered and displayed in Table 1. It can be observed that in case of PLA modified only by the addition of few-layered MoS2 (Fig. 4A) at loading of 0.5 wt% thermal decomposition proceeded at a slightly higher rate in comparison to pristine PLA, suggesting accelerated decomposition of polymer matrix as a result of flame retardant (FR) condensed phase action, which affected flow of the polymer38. As recorded in this case T10wt% value was lowered and was equal to 306 °C- it was 18 °C below that of a pristine PLA. In addition to this, further reduction in T50wt% and Tmax values in comparison to pristine PLA was also observed for this sample. In case of samples containing 1 wt% and 2 wt% of loading of few-layered MoS2 only Tmax was strongly affected which suggested that in both cases decomposition of polymer matrix proceeded at a normal rate in initial stages and stopped at a lower temperature. Therefore, it appears that addition of few-layered MoS2 nanoparticles has resulted in disruption of heat and gas diffusion. This effect was dependant on the FR load, as well as quality of dispersion in the polymer matrix. Combined with barrier effect, which limited access to fuel, it has caused the combustion process to finish at lower temperature. For samples containing addition of MoS2/Co2O3/CNT (Fig. 4B) a significant decrease in every recorded value was observed. T10wt% values were lowered by up to 40 °C for sample containing 0.5 wt% load of FR. T50wt% values were as much as 20 °C below that of pristine PLA for samples containing 0.5 wt% and 1 wt% FR load. Highest reduction in Tmax value was observed for sample containing 2 wt% load of FR and was 65 °C below that of pristine PLA. It appears that accelerated decomposition of the PLA matrix was caused by condensed action of the MoS2/Co2O3/CNT38. This resulted in pronounced flow of the polymer and its withdrawal from the sphere of influence. Change in melt-flow properties was confirmed during the preparation of samples for thermal conductivity testing. Composite samples needed to be preheated to glass transition temperature (about 150 °C) to form tablets using a table press. In case of PLA containing addition of MoS2/Co2O3/CNT the glass transition temperature appeared to be significantly lower (equal to about 110 °C) in comparison to another samples. In literature it was reported that poly(lactic acid) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) blends containing addition of isopropylated triaryl phosphate ester flame retardant displayed accelerated breakdown of polymer during the TGA testing, combined with accelerated melt dripping during the UL-94 rating testing, favouring the melt-flow drip mode of extinguishment3. As result of this, PLA/PMMA/FR blends have achieved V-0 classification in the UL-94 test3. In case of MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT (Fig. 4C) only a significant reduction in Tmax value was observed, which was highest (14 °C) for sample containing 2 wt% of nanomaterial, while the largest amount of charred reside was observed with sample containing 1 wt%. Recorded T10wt% and T50wt% values remained within the range of temperatures observed for pristine PLA. The composite samples containing addition of MoS2/Ni2O3/CNT (Fig. 4D) placed between those derived from Co2O3 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles – at lower FR loads polymer decomposition was accelerated but the stability of matrix increased with wt% of FR. In summary, obtained results suggest improved fire resistant performance due to disruption of heat and gas transfer within the composites, as well as barrier effect introduced through the addition of MoS2 and CNT.

CO content analysis performed with use of mass spectrometry during the TGA pyrolysis cycle in argon atmosphere revealed promising results. In each case the amount of CO released was lower in comparison to that observed for pristine PLA (Fig. 5). For PLA modified only with addition of few-layered MoS2 (Fig. 5A) the reduction in CO release ranged from 38 up to 70%, with the highest value recorded for sample containing 1 wt% of nanomaterials which also corresponded to the largest recorded charred residue value. Previously we observed that introduction of few-layered MoS2 into the poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) composite resulted in significant decrease (up to 94%) in permeability of hydrogen gas in comparison to pristine PVA39. This effect was attributed to the incorporation of impermeable MoS2 nanosheets with high aspect ratio. As a result a high number of tortuous pathways was created which restricted the diffusion of penetrants, such as H2 or CO39,40. Reduction of CO emission during pyrolysis was further enhanced in case of MoS2/MxOy/CNT composites. Highest reduction of CO emission in respect to pristine PLA was observed for all samples containing MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT (Fig. 5C), and it was always above 90%. This was attributed to a well developed and thermally stable char barrier, which protected the molten zone from the burning zone, as reported by Attia et al.41 in case of polystyrene composites containing addition of MWCNT.

Flammability studies

Fire performance testing was conducted using MCC, which allowed for laboratory evaluation of fire resistant properties of composites. Examples of heat release rate curves of prepared composites were presented in Fig. 6. Average values for key parameters - pHRR, HRC and THR were calculated from three measurements for each sample and presented in Table 2. All of these values were lowered for samples containing the addition of FR in comparison to pristine PLA. The samples containing an addition of MoS2 (Fig. 6A) showed satisfying FR performance with significant decrease of pHRR and THR values in comparison to pristine PLA. Therefore, it was evident that the addition of MoS2 into the PLA matrix introduced the barrier effect which effectively impeded oxygen filtration, heat and mass transmission and the release of combustible gases produced during the combustion process, as previously reported for PVA, polystyrene (PS) and PMMA11,42,43. Formation of this barrier prevented underlying material from further combustion. For composite samples containing addition of MoS2/MxOy/CNT FR best results were observed for 2 wt% load. This effect could be attributed to strong barrier effect due to formation of an enhanced char layer thanks to the presence of CNT21,44. In case of samples containing addition of MoS2/Co2O3/CNT (Fig. 6B) and MoS2/Ni2O3/CNT (Fig. 6D) there was a visible shoulder within the temperature range of 250–350 °C. This suggested occurrence of an overlapping stage, preceding main combustion of PLA. This may be attributed to the release of FR additive via vaporisation or cleavage. In addition, a secondary peak was also observed for those samples within the temperature range of 425–515 °C which could be attributed to the increase in volume of sample due to intumescence. The intensity of this peak decreased with increase in FR loading, which suggests that rigidity of the barrier was directly tied to the FR contents and it is optimal at 2 wt%. While both of the effects could be also observed for samples containing addition of MoS2 as well as MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT (Fig. 6C), the size of the before mentioned shoulder as well as intensity of the secondary peak were much lower.

Thermal conductivity

In order to verify thermal conductivity of obtained composites samples with a diameter of 12.7 mm were prepared using tablet press. For each composite a batch of 3 tablets were prepared. Thickness of each tablet was measured and recorded. In order to facilitate laser adsorption at the surface all tablets were covered with a thin layer of graphite prior to measurement. Tests were carried out at room temperature, which was measured at 25.4 °C. Obtained data (average out of 3 tablets for each composite) was presented in Table 3. In case of samples prepared with addition of only few-layered MoS2 highest level of thermal conductivity – 0.502 Wm−1K−1 was observed for sample containing addition of 2 wt% of FR and it was 54% higher than that of a pristine PLA sample. Similar effects were reported in literature for epoxy samples containing addition of nanomaterial such as graphene oxide or graphene nanosheets45. For samples containing CNT based structures thermal conductivity increased with increase in loading, resulting in up to 0.538 Wm−1K−1 or a 65% increase over pristine PLA in case of a sample containing 2 wt% of MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT. It is however worth noting that even in case of 0.5 wt% of MoS2/Ni2O3/CNT a 50.9% increase in thermal conductivity was observed. Kashiwagi et al. also observed similar increase in thermal conductivity in case of polypropylene composites containing addition of carbon nanotubes which suggests that further enhancement of thermal conductivity of CNT based composites could be attributed to their presence46.

Conclusions

In this work, in order to improve fire performance of PLA, few-layered MoS2 and MoS2/MxOy/CNT nanomaterials were prepared and introduced into the PLA composites through twin-screw extrusion blending process. TGA analysis revealed 40 °C and 65 °C decrease of Tmax value for samples containing 0.5 wt% of few-layered MoS2 and 2 wt% of MoS2/Co2O3/CNT, respectively. Thanks to the addition of few-layered MoS2 a formation of charred residue layer was observed which allowed for up to nearly 70% decrease in CO emission during burning in case of a sample containing 1 wt% of MoS2. Over 90% of reduction in CO emission was achieved through introduction of MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT into the PLA matrix. MCC analysis showed best performance of few-layered MoS2 and MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT composites, while MoS2/Co2O3/CNT and MoS2/Ni2O3/CNT composites displayed strong effects of secondary stage preceding the main combustion of PLA as well as instability of barrier at 0.5 wt% and 1 wt% of FR. Thermal conductivity of all of the composites was increased in comparison to pristine PLA, up to 65% in case of a composite containing addition of 2 wt% of MoS2/Fe2O3/CNT due to the presence of CNT. In conclusion, introduction of few-layered MoS2 and CNT functionalized MoS2 nanomaterials shows good potential for reduction of fire hazard of the PLA, which could prove beneficial for academic research and practical applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bocz, K. et al. Flame retarded self-reinforced poly(lactic acid) composites of outstanding impact resistance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 70, 27–34 (2015).

Fox, D. M., Lee, J., Citro, C. J. & Novy, M. Flame retarded poly(lactic acid) using POSS-modified cellulose. Polym Degrad Stab. 98, 590–6 (2013).

Teoh, E. L., Mariatti, M. & Chow, W. S. Thermal and Flame Resistant Properties of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Blends Containing Halogen-free Flame Retardant. Procedia Chem 19, 795–802 (2013).

Zhao, X., Gao, S. & Liu, G. A. THEIC-based polyphosphate melamine intumescent flame retardant and its flame retardancy properties for polylactide. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 122, 24–34 (2016).

Liu, X. Q., Wang, D. Y., Wang, X. L., Chen, L. & Wang, Y. Z. Synthesis of functionalized α-zirconium phosphate modified with intumescent flame retardant and its application in poly(lactic acid). Polym Degrad Stab 98, 1731–7 (2013).

Liao, F. et al. A novel efficient polymeric flame retardant for poly (lactic acid) (PLA): Synthesis and its effects on flame retardancy and crystallization of PLA. Polym Degrad Stab 120, 251–61 (2015).

Costes, L. et al. Phosphorus and nitrogen derivatization as efficient route for improvement of lignin flame retardant action in PLA. Eur Polym J 84, 652–67 (2014).

Fontaine, G. & Bourbigot, S. Intumescent polylactide: A nonflammable material. J Appl Polym Sci 113, 3860–5 (2009).

Qian, Y. et al. Aluminated mesoporous silica as novel high-effective flame retardant in polylactide. Compos Sci Technol 82, 1–7 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. Intercalation of phosphotungstic acid into layered double hydroxides by reconstruction method and its application in intumescent flame retardant poly (lactic acid) composites. Polym Degrad Stab 147, 142–50 (2013).

Zhou, K., Liu, J., Zeng, W., Hu, Y. & Gui, Z. In situ synthesis, morphology, and fundamental properties of polymer/MoS2 nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 107, 120–8 (2013).

Wang, D., Xing, W., Song, L. & Hu, Y. Space-Confined Growth of Defect-Rich Molybdenum Disulfide Nanosheets Within Graphene: Application in the Removal of Smoke Particles and Toxic Volatiles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 8, 34735–43 (2016).

Zhou, K. et al. Comparative study on the thermal stability, flame retardancy and smoke suppression properties of polystyrene composites containing molybdenum disulfide and graphene. RSC Adv 3, 25030 (2013).

Guo, Y. et al. Capitalizing on the molybdenum disulfide/graphene synergy to produce mechanical enhanced flame retardant ethylene-vinyl acetate composites with low aluminum hydroxide loading. Polym Degrad Stab 144, 155–66 (2017).

Hong, N. et al. Facile preparation of graphene supported Co3O4 and NiO for reducing fire hazards of polyamide 6 composites. Mater Chem Phys 142, 531–8 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. The effect of metal oxide decorated graphene hybrids on the improved thermal stability and the reduced smoke toxicity in epoxy resins. Chem Eng J 250, 214–21 (2018).

Wang, X., Kalali, E. N., Wan, J.-T. T. & Wang, D. Y. Y. Carbon-family materials for flame retardant polymeric materials. Prog Polym Sci 69, 22–46 (2017).

Kashiwagi, T. et al. Flammability properties of polymer nanocomposites with single-walled carbon nanotubes: Effects of nanotube dispersion and concentration. Polymer (Guildf) 46, 471–81 (2005).

Hapuarachchi, T. D. & Peijs, T. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes and sepiolite nanoclays as flame retardants for polylactide and its natural fibre reinforced composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 41, 954–63 (2016).

Kashiwagi, T. et al. Thermal degradation and flammability properties of poly(propylene)/carbon nanotube composites. Macromol Rapid Commun 23, 761–5 (2002).

Verdejo, R. et al. Carbon nanotubes provide self-extinguishing grade to silicone-based foams. J Mater Chem 18, 3933 (2008).

Zúñiga, C. et al. Convenient and solventless preparation of pure carbon nanotube/polybenzoxazine nanocomposites with low percolation threshold and improved thermal and fire properties. J Mater Chem A 2, 6814–22 (2014).

Wu, Q., Zhu, W., Zhang, C., Liang, Z. & Wang, B. Study of fire retardant behavior of carbon nanotube membranes and carbon nanofiber paper in carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composites. Carbon N Y 48, 1799–806 (2010).

Wang, L. & Jiang, P. K. Thermal and flame retardant properties of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer/modified multiwalled carbon nanotube composites. J Appl Polym Sci 119, 2974–83 (2011).

Kuan, C. F. et al. Flame retardance and thermal stability of carbon nanotube epoxy composite prepared from sol–gel method. J Phys Chem Solids 71, 539–43 (2010).

He, Q. et al. Flame-Retardant Polypropylene/Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites: Effects of Surface Functionalization and Surfactant Molecular Weight. Macromol Chem Phys 215, 327–40 (2013).

Xu, G. et al. Functionalized carbon nanotubes with oligomeric intumescent flame retardant for reducing the agglomeration and flammability of poly(ethylene vinyl acetate) nanocomposites. Polym Compos 34, 109–21 (2013).

Peeterbroeck, S. et al. Mechanical Properties and Flame-Retardant Behavior of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate/High-Density Polyethylene Coated Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites. Adv Funct Mater 17, 2787–91 (2007).

Ma, H. Y., Tong, L. F., Xu, Z. B. & Fang, Z. P. Functionalizing Carbon Nanotubes by Grafting on Intumescent Flame Retardant: Nanocomposite Synthesis, Morphology, Rheology, and Flammability. Adv Funct Mater 18, 414–21 (2008).

Song, P., Xu, L., Guo, Z., Zhang, Y. & Fang, Z. Flame-retardant-wrapped carbon nanotubes for simultaneously improving the flame retardancy and mechanical properties of polypropylene. J Mater Chem 18, 5083 (2008).

Pal, K., Kang, D. J., Zhang, Z. X. & Kim, J. K. Synergistic Effects of Zirconia-Coated Carbon Nanotube on Crystalline Structure of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanocomposites: Electrical Properties and Flame-Retardant Behavior. Langmuir 26, 3609–14 (2016).

Zhang, T., Du, Z., Zou, W., Li, H. & Zhang, C. The flame retardancy of blob-like multi-walled carbon nanotubes/silica nanospheres hybrids in poly (methyl methacrylate). Polym Degrad Stab 97, 1716–23 (2012).

Du, B. & Fang, Z. The preparation of layered double hydroxide wrapped carbon nanotubes and their application as a flame retardant for polypropylene. Nanotechnology 21, 315603 (2014).

Gao, F., Beyer, G. & Yuan, Q. A mechanistic study of fire retardancy of carbon nanotube/ethylene vinyl acetate copolymers and their clay composites. Polym Degrad Stab 89, 559–64 (2005).

Ma, H., Tong, L., Xu, Z. & Fang, Z. Synergistic effect of carbon nanotube and clay for improving the flame retardancy of ABS resin. Nanotechnology 18, 375602 (2007).

Wang, X., Feng, H., Wu, Y. & Jiao, L. Controlled synthesis of highly crystalline MoS2 flakes by chemical vapor deposition. J Am Chem Soc 135, 5304–7 (2013).

Placidi, M. et al. Multiwavelength excitation Raman scattering analysis of bulk and two-dimensional MoS2: Vibrational properties of atomically thin MoS2 layers. 2D Mater 2, 035006 (2015).

Bourbigot, S. & Fontaine, G. Flame retardancy of polylactide: An overview. Polym Chem 1, 1413–22 (2010).

Thakur, S., Bandyopadhyay, P., Kim, S. H., Kim, N. H. & Lee, J. H. Enhanced physical properties of two dimensional MoS2/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 110, 284–93 (2018).

Huang, H. D. et al. High barrier graphene oxide nanosheet/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite films. J Memb Sci 409, 156–63 (2012).

Attia, N. F., Afifi, H. A. & Hassan, M. A. Synergistic Study of Carbon Nanotubes, Rice Husk Ash and Flame Retardant Materials on the Flammability of Polystyrene Nanocomposites. Mater. Today Proc. 2, 3998–4005 (2015).

Zhou, K., Gao, R., Gui, Z. & Hu, Y. The effective reinforcements of functionalized MoS2 nanosheets in polymer hybrid composites by sol-gel technique. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 94, 1–9 (2015).

Zhou, K., Tang, G., Gao, R. & Guo, H. Constructing hierarchical polymer@MoS2 core-shell structures for regulating thermal and fire safety properties of polystyrene nanocomposites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 107, 144–54 (2018).

Aschberger, K., Campia, I., Pesudo, L. Q., Radovnikovic, A. & Reina, V. Chemical alternatives assessment of different flame retardants – A case study including multi-walled carbon nanotubes as synergist. Pergamon 107, 27–45 (2017).

Liu, S., Chevali, V. S., Xu, Z., Hui, D. & Wang, H. A review of extending performance of epoxy resins using carbon nanomaterials. Compos Part B Eng 136, 197–214 (2018).

Kashiwagi, T. et al. Thermal and flammability properties of polypropylene / carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Polymer (Guildf) 45, 4227–39 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the National Science Centre Poland OPUS 10 UMO-2015/19/B/ST8/00648. Research project funded by National Science Centre Poland OPUS 10 UMO-2015/19/B/ST8/00648.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H. prepared all of the samples, gathered, analyzed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. E.M. helped with interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. K.W. prepared TEM images, TGA, XRD and Raman spectroscopy data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Homa, P., Wenelska, K. & Mijowska, E. Enhanced thermal properties of poly(lactic acid)/MoS2/carbon nanotubes composites. Sci Rep 10, 740 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57708-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57708-1

This article is cited by

-

Polymer Blend Nanoarchitectonics with Exfoliated Molybdenum Disulphide/Polyvinyl Chloride/Nitrocellulose

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2023)

-

Two-Stage Modeling of Tensile Strength for a Carbon-Nanotube-Based System Applicable in the Biomedical Field

JOM (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.