Abstract

We investigated the effect of a combination treatment with dapagliflozin (Dapa), a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor and butyrate on weight change in db/db mice. Six-week-old male db/db mice were assigned to four groups: vehicle with normal chow diet (NCD), Dapa with NCD, vehicle with 5% sodium butyrate-supplemented NCD (NaB), or Dapa with 5% NaB. After six weeks of treatment, faecal microbiota composition was analysed by sequencing 16S ribosomal RNA genes. In the vehicle with NaB and Dapa + NaB groups, body weight increase was attenuated, and amount of food intake decreased compared with the vehicle with the NCD group. The Dapa + NaB group gained the least total and abdominal fat from baseline. Intestinal microbiota of this group was characterized by a decrease of the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, a decrease of Adlercreutzia and Alistipes, as well as an increase of Streptococcus. In addition, the proportion of Adlercreutzia and Alistipes showed a positive correlation with total fat gain, whereas Streptococcus showed a negative correlation. Inferred metagenome function revealed that tryptophan metabolism was upregulated by NaB treatment. We demonstrated a synergistic effect of Dapa and NaB treatment on adiposity reduction, and this phenomenon might be related to intestinal microbiota alteration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes and its complications, and increase in adiposity causes severe problems for diabetes management1,2. However, treatment of hyperglycaemia may induce weight gain due to diminished calorie loss through glycosuria3. In contrast to traditional oral hypoglycaemic agents, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, a new class of oral medications, cause glycosuria and lead to pronounced calorie loss4. According to a recent meta-analysis, long-term treatment with SGLT-2 inhibitors led to a loss of 1–2 kg of body weight5. Therefore, SGLT-2 inhibitors are promising treatment options for diabetes as they reduce both hyperglycaemia and obesity.

In preclinical and clinical studies using SGLT-2 inhibitors, weight reduction was generally observed5,6,7, although the magnitude of weight reduction was less than expected8. One factor that is believed to prevent weight loss is compensatory hyperphagia8. Therefore, we need additional intervention strategies to control appetite and modulate adiposity when using SGLT-2 inhibitors. After SGLT-2 inhibitor treatment, a relative increase in glucagon level can induce lipolysis9. However, beta-hydroxybutyrate, the end-product of free fatty acid oxidation, inhibits lipolysis via negative feedback10. As a result, fat cells can reach equilibrium, and lipolysis might not be increased in the long term. Given this condition, administering a substance to induce lipolysis continuously may enhance the reduction in fat mass.

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that is produced by fermentation of dietary fibre by gut microbiota11. In a human study, the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria was increased in subjects with normal glucose tolerance compared with patients with diabetes12. An in vitro study showed that butyrate directly induced lipolysis in 3T3L-1 adipocytes13. Short-chain fatty acids including butyrate can be increased by the role of gut microbiota, which may then induce the production of gut-derived serotonin14, which plays a role in increasing lipolytic enzyme activity15. In mouse models of diet-induced obesity, butyrate attenuated weight gain and improved insulin resistance without decreasing food intake16,17. In other studies, appetite can be controlled by chronic administration of butyrate, which enhances intestinal gluconeogenesis18, modulates nutrient sensing, and augments gut hormones that inhibit the appetite centre in the hypothalamus19. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that butyrate treatment would induce lipolysis and control food intake in an db/db mouse model under dapagliflozin treatment. In addition, we investigated the alteration of gut microbiota composition and its plausible role in modulating host adiposity.

Results

Effects of dapagliflozin and butyrate on body weight, food intake, and glucose metabolism in db/db mice

The percent changes of body weight were not different between the Veh group and the Dapagliflozin (Dapa) group. However, it was significantly lower in the Dapa + sodium butyrate (NaB) group than in the Vehicle (Veh) group (Fig. 1A). The average food intake during 24 h during 6-week observation was comparable between the Veh group and the Dapa group, but it was decreased in the NaB and Dapa + NaB groups compared with the Veh group (Fig. 1B). Serial random glucose levels were lower in the Dapa + NaB group (starting from week three) and in the Dapa and NaB groups (starting from week five) than in the Veh group (Fig. 1C). At week four, glucose levels decreased more in the Dapa + NaB group than in the Dapa group. We also detected a decrease of HbA1c levels in these three treatment groups compared with the Veh group (Fig. 1D). During oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs), glucose excursion in these groups was markedly decreased compared with the Veh group (Fig. 1E,F).

Serial percent changes of body weight (A), food intake during 24 h (B), serial levels of random glucose (C), HbA1c levels after six weeks of treatment (D), glucose profiles during oral glucose tolerance tests (E), and area under the curve of glucose levels (F). Data are represented as mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 vs. Veh + NCD, †P < 0.05 vs. Dapa + NCD.

Fat mass change, and fat and liver histology

Both fat and abdominal fat gain from baseline was not decreased in the Dapa group compared to the Veh group. In the Dapa + NaB group, fat gain was more attenuated than the Dapa group (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, abdominal fat gain was also lower in the Dapa + NaB group than in the Dapa or NaB groups (Fig. 2B). Multilocular lipid droplets of brown adipose tissue (BAT) were found by haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in the Dapa + NaB group (Fig. 2D). The mean adipocyte diameter in inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT) was decreased in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the Veh group (Fig. 2E,G), and small-sized adipocytes in iWAT tended to be increased in the Dapa + NaB group (Fig. 2H). Liver weight was decreased, and fat accumulation in the liver was attenuated in the Dapa, NaB, and Dapa + NaB groups than the Veh group (Fig. 2C,F).

Fat gain from baseline (A), abdominal fat gain from baseline (B), liver weight (C), H&E staining of brown adipose tissue. Scale bars, 200 µm (D), inguinal white adipose tissue. Scale bars, 200 µm. Images on the right are high-magnification images (E), and liver. Scale bars, 200 µm (F), adipocyte diameter (G), and adipocyte size distribution of inguinal white adipose tissue (H). Data are represented as mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05 vs. Veh + NCD, ††P < 0.01 vs. Dapa + NCD, ‡‡P < 0.001 vs. Veh + NaB.

Plasma levels of metabolic hormones and lipolysis-related gene expression in iWAT

Fasting insulin levels tended to be higher in the NaB group than in the Veh group (10.4 ± 1.7 vs. 4.8 ± 1.3 ng/ml, P = 0.057) (Fig. 3A). Accordingly, homeostatic model assessment of beta cell function (HOMA-beta) was higher in the NaB group than in the Veh group (Fig. 3B), but HOMA-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was comparable between groups (Fig. 3C). Glucagon levels were higher in the Dapa + NaB group than in the Veh group (Fig. 3D). The insulin to glucagon ratio (IGR) was decreased in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the NaB group (24.1 ± 6.6 vs. 87.3 ± 21.4 mol/mol, P = 0.032) (Fig. 3E). There was no significant difference in plasma levels of resistin and peptide YY (PYY) between groups (Fig. 3F,G). The fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF-21) levels were significantly increased in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the NaB group (85.0 ± 30.3 vs. 481.4 ± 162.6 pg/ml, P = 0.016) (Fig. 3H). There was higher mRNA expression of perilipin 1 (Plin1), and adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) in iWAT of the NaB group compared with the Veh group (Fig. 3I,J). The mRNA expression of hormone-sensitive lipase (Hsl) in iWAT was increased in the Dapa + NaB group than the Dapa group (Fig. 3K). The activating transcription factor 2 (Atf2) in iWAT derived from Dapa + NaB group was higher compared with the Veh and the Dapa groups (Fig. 3I–L).

Plasma levels of insulin (A), HOMA-beta (B), HOMA-IR (C), plasma levels of glucagon (D), insulin to glucagon ratio (E), plasma levels of resistin (F), peptide YY (G), and FGF-21 (H), mRNA expression of perilipin 1 (I), adipose triglyceride lipase (J), hormone-sensitive lipase (K), and activating transcription factor 2 (L) in inguinal white adipose tissue. Data are represented as mean ± standard error. *P < 0.05 vs. Veh + NCD, ††P < 0.01 vs. Dapa + NCD, ‡P < 0.05 vs. Veh + NaB.

Tryptophan hydroxylase-1 and tight junction protein gene expression in intestine

The mRNA expression of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Thp-1), a rate liming enzyme for serotonin synthesis14 was higher in ileum of the NaB and Dapa + NaB groups than Veh or Dapa groups (Fig. 4A). In colon tissue, the mRNA expression of Thp-1 showed the increased tendency in the Dapa + NaB group compared to other groups (Fig. 4E). In addition, Claudin (Cldn) was significantly higher in the NaB group than the Veh group or the Dapa group (Fig. 4D), but mRNA levels of other tight junction protein did not show any significant difference between groups (Fig. 4B,C). In colon, Zo-2 of Dapa + NaB group was higher than the Dapa group, and Cldn of NaB and Dapa + NaB groups was higher than the Veh group (Fig. 4F,H). There was no difference in Occludin mRNA level between groups (Fig. 4G).

Distinct gut microbiota composition following NCD versus NaB treatment

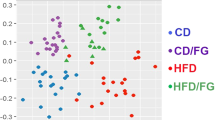

To identify the intestinal microbiota composition in the mice of the four treatment groups, we collected mice stool samples and conducted 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq platform. From the stool samples, a total of 2,366,458 merged sequences and 58,624 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were obtained. We found a significant decrease of microbial diversity in the NaB-treated group, regardless of additional Dapa treatment (Fig. 5A). Principal co-ordinate analysis (PCoA) analysis with weighted UniFrac distances confirmed the heterogeneity of gut microbiota among the four treatment groups. A clear separation between gut microbial communities, driven by NaB, was observed (Fig. 5B). Analysis at the phylum level revealed that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was decreased in the Dapa group, but it was increased following NaB treatment (Fig. 5C). The relative ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes was increased in the Dapa group compared with the Veh group, but it was decreased in the NaB and NaB + Dapa groups compared with the Veh or Dapa groups (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the heat map shows significantly different OTUs in the four treatment groups, with a logarithmic linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score of ≥3.0 as determined by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis (Fig. 5D). The relative abundance of OTUs was well separated by the presence of NaB.

α-Diversity (Chao1) comparison of the gut microbiota of the four treatment groups (A), PCoA plot of weighted UniFrac distances based on 97% similar OTUs across the different groups (B), composition of abundant bacterial phyla in the gut microbiota (C), relative ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (E), and heat map for significantly different OTUs determined by LEfSe analysis (LDA >3.0) according to treatment groups (D).

Microbiota signature changes in relation to body fat change

At the genus level, the mice intestinal microbiota differed in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the Veh group. The relative abundance of the genera Alistipes, Anaerotruncus, Mucispirillum, and Oscillospira was markedly decreased in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the Veh group (Fig. 6A). Compared with the Dapa group, Adlercreutzia, Alistipes, Anaerotruncus, Mucispirillum, and Oscillospira abundance was also decreased in the Dapa + NaB group. However, Streptococcus abundance was significantly increased in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the Dapa group. Interestingly, the amount of fat gain was positively correlated with relative abundance of Adlercreutzia and Alistipes, but negatively correlated with Streptococcus (Fig. 6B).

Characterization of gut microbiota functionality

Metagenome functionality analysis, inferred from the 16S rRNA gene sequences, revealed that amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism were the top three upregulated pathways in the Veh and Dapa groups (Fig. 7a,b). However, glycosaminoglycan degradation, glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism, and D-alanine metabolism were commonly upregulated in the NaB and Dapa + NaB groups (Fig. 7c,d). Interestingly, tryptophan metabolism was commonly upregulated in the NaB and Dapa + NaB groups but it was not upregulated in the other groups.

Discussion

Chronic treatment with dapagliflozin did not reduce body weight and fat gain in db/db mice. However, cotreatment with butyrate and dapagliflozin attenuated increasing adiposity in this mouse model. In addition, butyrate itself can modulate food intake and hyperglycaemia. The combination treatment of butyrate and dapagliflozin increased intestinal serotonin producing enzyme and may have increased lipolysis. The anti-obesity effects of butyrate were highly correlated with alterations of gut microbiota composition, especially the decrease of Adlercreutzia and Alistipes, and the increase of Streptococcus.

The main mechanism of butyrate that modulated adiposity was the decrease of food intake. Interestingly, even though there was no difference in food intake between butyrate monotherapy and the combination treatment with dapagliflozin and butyrate, abdominal fat gain was markedly decreased with the combination treatment compared with butyrate monotherapy. However, the effect of combination treatment on the abdominal fat was not solely related with gut microbiota because there was no big difference in the microbiota composition between the Veh + NaB and Dapa + NaB groups. The main contributor for microbiota change was butyrate. Therefore, we did not see further microbiota change after the dapagliflozin add-on therapy to butyrate compared with butyrate monotherapy. There might be other contributor to regional fat tissue modulation when this combination treatment is used. Histologic analysis revealed decreased diameter of adipocytes and increased proportions of small adipocytes in the combination treatment group. There was evidence that butyrate directly induced fat lipolysis13, and the relative increase of glucagon after SGLT-2 inhibitor treatment could induce breakdown of fat and lead to the use of fatty acids as energy source20,21. Therefore, this combination treatment might be efficient in inducing fat lipolysis. In the same context, we observed higher plasma levels of FGF-21, a key regulator of lipolysis22, and lower levels of IGR in the Dapa + NaB group compared with the NaB group. A recent longitudinal observational study also showed that abnormal subcutaneous fat-cell lipolysis is related to long-term weight gain23. Interestingly, we observed higher Atf2 mRNA levels in iWAT of the Dapa + NaB group compared with the Veh and Dapa groups. ATF2 has been revealed to bind at the Fgf21 gene promoter region and induce Fgf21 gene transcription24. Therefore, efficient fat lipolysis after cotreatment with butyrate and dapagliflozin might be regulated by the ATF2–FGF-21 axis. Furthermore, the increase of glucagon and the decrease of IGR could be related with increase of thermogenesis25 in the combination treatment. In summary, combination treatment reduced abdominal fat much more than single treatments via both the alteration of microbiota and induction of glucagon action, but this hormonal change was not directly associated with microbiota composition.

Butyrate reduced hyperglycemia as much as dapagliflozin did. Butyrate reduced food intake and dapagliflozin induced glycosuria; these mechanisms were distinct from each other. However, we unfortunately did not see a further decrease of hyperglycemia in the combination treatment. In our experiment, we treated butyrate in db/db mice at an early stage of obesity and diabetes from when they were six weeks old. The db/db mice develop hyperphagia-induced obesity and diabetes26. Therefore, the initiation timing of butyrate might be a critical factor to prevent weight gain and severe hyperglycaemia through reducing food intake. Under butyrate, the effect of dapagliflozin might not be apparent in terms of glucose-lowering ability. However, human obesity and diabetes are generally developed by multifactorial conditions rather than just by hyperphagia. From this clinical perspective, it is necessary to test butyrate as a supplement with other anti-diabetic or anti-obesity medication in human studies.

Butyrate is normally produced in high concentration by bacterial fermentation in the distal intestine11. However, we administered NaB mixed into the diet as a supplement. Therefore, butyrate was primarily absorbed via the upper intestine and was not likely to stimulate the distal part of the gut where enteroendocrine cells are abundantly expressed. In addition, plasma PYY levels were not increased in the NaB-treated groups. A previous study also found no increase in distal gut hormones after oral butyrate administration, which contradicts findings reported using a high-fibre diet27. Even though there was the possibility that butyrate did not reach the distal intestine, this intervention altered overall gut microbiota composition. The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was increased in the NaB-treated groups, and that of Firmicutes was decreased. The decreased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes was also observed in a previous study that tested the effects of butyrate administered by oral gavage in db/db mice28. That study showed anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate and its protective role in gut epithelial barrier integrity. Butyrate has a possible role in the modulation of intestinal immunity. Butyrate treatment activates regulatory T cells29 and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced-proinflammatory mediators produced by intestinal macrophages30. Another possible explanation is that the reduction in food intake per se may modulate the microbiota composition. One study found that a low-calorie diet changes the gut microbiota composition31. In our experiments, the expression of the gene encoding intestinal tight junction protein was increased after butyrate treatment. The loss of intestinal integrity could induce low-grade systemic inflammation and finally increase metabolic disorders32. In addition, tryptophan metabolism was upregulated by butyrate treatment, and this upregulation was related to the induction of intestinal serotonin production14. Our findings suggest that butyrate can modulate both gut health and function by changing the gut microbial composition, which may alter aspects of host metabolism such as lipolysis activity.

A previous study using a human-like, diet-induced mice model of obesity also reported microbiota alteration in the faeces after butyrate treatment, and it demonstrated that oral administration of butyrate alone can—in contrast to intravenous administration—suppress food intake33. However, food intake was not reduced after butyrate treatment in vagotomized mice33. Therefore, the metabolic effects of butyrate might be driven via the intestine rather than via direct effects on the central nervous system. If we had used butyrate and dapagliflozin in vagotomized mice model or performed pair-fed experiments, we would have a clear idea about a direct effect of this combination in adipose tissue excluding the effect of calorie restriction.

It is controversial whether the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteriodetes is relates with obesity34 and the role of microbial diversity in obesity is also controversial35. Obesity has been reported to be related to reduced microbial diversity36, but our result and those of others37,38 show reduced microbial diversity even after improvements in host metabolism. It is necessary to consider the altered composition of microbiota in more specific levels and its crosstalk with host. In our study, we showed that Streptococcus, belonging to the Firmicutes phylum, was negatively correlated with fat mass gain, whereas the abundance of Alistipes, within the Bacteroidetes phylum, correlated positively with fat mass gain. A previous study also showed similar association between Alistipes and body fat and inflammatory cytokines39,40. In contrast, using the data from 1,914 Chinese adults, Zeng et al. reported that Alistipes was negatively associated with metabolic abnormalities such as obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia41. Therefore, ethnicity or dietary habits might influence the abundance of Alistipes. In fact, dietary intervention in human studies rapidly altered the microbial composition; for example, Alistipes was increased after an animal-based diet42. In an experimental model, Alistipes was also increased after a high fat diet43. In summary, there were discrepancies in the results of the alteration of Alistipes according to host metabolic status. However, Alistipes might be positively related with obesity, at least in the well-controlled animal experiments39,43. Proof of a direct effect of Alistipes on adiposity will require studies of faecal transplantation or therapeutic administration. In the case of Adlercreutzia, obesity was positively correlated with the high abundance of Adlercreutzia in human studies44,45.

The current study has several limitations. First, we did not compare the metabolic effects with pair-fed groups. However, dapagliflozin monotherapy did not induce hyperphagia as initially expected. Therefore, it is not necessary to match the food intake of the Dapa and Veh groups. Second, we cannot demonstrate a role of gut microbiota in reducing adiposity, because we did not perform faecal transplantation. Third, there were no data on energy expenditure, which could provide insight into the changes of metabolic rates after intervention. Fourth, we used genetically obese mouse model. Therefore, there is a gap between current observation and human biology. Butyrate directly increases leptin expression in adipocytes46 but reduces systemic leptin level in vivo after chronic treatment47; the latter effect may relate to the reduction in whole-body fat mass. Therefore, the systemic leptin level may increase in short-term experiments but may decrease after long-term treatment. However, there was no published evidence that butyrate can recover leptin resistance. In our experiments, we excluded an effect of leptin by using leptin receptor-knockout mice. Butyrate supplementation combined with an SGLT-2 inhibitor should be tested in a high-fat diet-induced obesity mouse model. Obese people with type 2 diabetes may also be a good candidate group for studies to confirm the anti-obesity effect of the combined treatment of butyrate and an SGLT-2 inhibitor. In contrast to GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT-2 inhibitors are the only oral anti-diabetic medication shown to reduce body weight, and they have potential for wide use. Further research is needed to study the effects of other supplements to boost the anti-obesity effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors. Butyrate may be one candidate for application in human studies.

In conclusion, butyrate supplement reduced fat and, in combination with dapagliflozin, further modulated abdominal obesity. Alterations in gut microbiota composition and functionality were related to the anti-obesity effects of butyrate.

Methods

Study animals and treatment

Five-week-old male db/db mice (Envigo, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) were housed in a light- and temperature-controlled facility. To minimize the inter-group difference at baseline, after one week of adaptation, the mice were assigned to four groups according to their body weight and random glucose levels: (1) veh with chow diet (LabDiet 5L79, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA) (Veh group); (2) Dapa (U Chem Co., Anyang-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) with NCD (Dapa group); (3) veh with 5% NaB-supplement NCD (303410, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (NaB group); and (4) Dapa with 5% NaB-supplement NCD (Dapa + NaB group). Dapagliflozin (1 mg/kg) or veh (normal saline) was administered daily via oral gavage for six weeks. The dosages of butyrate and dapagliflozin were chosen based on previous studies of their anti-obesity16,17 and anti-diabetic effects48,49. All animals were allowed food and water ad libitum. Whole body and abdominal fat were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (InAlyzer, Medikors, Seoul, Korea) under general anesthesia with 2% isoflurane. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, South Korea (No. BA 1511-188/072-04). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines on the use of laboratory animal of Seoul National University and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

Oral glucose tolerance test

After six weeks of treatment, OGTTs were performed after 15 h of fasting. Baseline blood glucose levels were measured and then glucose (0.5 g/kg body weight) was given orally as a 20% solution. Serial glucose measurements were performed at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min using an Accu-Chek Performa glucometer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Biochemical analysis

Fasting blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture in mice anesthetized with Zoletil 50 (zolazepam plus tiletamine, Virbac Laboratories, Carros, France). Blood was collected into EDTA tubes containing aprotinin 500 KIU/mL. The tubes were placed on ice immediately and centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Plasma was stored at –80 °C until used for biochemical analysis. HbA1c levels were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (Arkray Inc., Kyoto, Japan) according to the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program standard at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital’s central laboratory. Insulin, glucagon, resistin, and PYY were measured using a Milliplex Mouse Metabolic Hormone Panel (MMHMAG-44K, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). HOMA-IR and HOMA-beta were calculated using fasting glucose and insulin levels50. The IGR was assessed by a previously reported method21. Plasma FGF-21 concentrations were measured using an ELISA kit (Biovender, Brno, Czech Republic).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from iWAT, distal ileum, and colon samples using TRIzol (Ambion, CA, USA). For quantitative real-time PCR analysis, we followed the previously published method51. The 3 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). SYBR Green reactions using the SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) were assembled along with 10 pM primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were performed using the Applied Biosystems ViiA7 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the comparative CT method and normalized to cyclophilin mRNA for iWAT and GAPDH mRNA for distal ileum and colon. mRNA expression levels are displayed relative to Veh control mRNA as specified for each experiment. The sequences of all primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Histology of adipose tissue

Mice were sacrificed by cardiac puncture under anaesthesia. The iWAT from bilateral inguinal area, BAT from the interscapular area, and the liver were collected and fixed in 10% neutral formaldehyde. Remaining tissue was frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Paraffin sections were made and stained with H&E. Slides were scanned with a photomicroscope (Axioskop 40, Carl Zeiss, Germany). We manually drew the maximal diagonal length of each adipocyte in calculating adipocyte diameters.

Faecal DNA extraction and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 0.25 g of each mouse stool sample using the QIAamp PowerFecal Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Amplification of the V4–V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed by PCR using the bacterial-specific primers, 518 F (5′-TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG CCA GCA GCY GCG GTA AN-3′) and 927 R (5′-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA GCC GTC AAT TCN TTT RAG T-3′). The conditions of thermal cycling were 95 °C for 3 min for denaturation, 25 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s), and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The barcoded sequences (Illumina Nextera XT Index Kit v2, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), were incorporated using index PCR primers under the same conditions. Each sample was quantified and qualified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and samples were pooled for MiSeq sequencing performed by Macrogen Corp (Illumina, Seoul, Korea). The raw sequence data used in this study were uploaded to SRA with the accession number SRR8371999 to SRR8372017.

Bacterial phylogenetic analysis

The raw sequencing data were processed and merged using a Python script, iu-merg-pairs (REF) with default options (minimum overlap region size: 15, minimum quality score: 15)52 and the merged paired-end sequences were analysed using the QIIME (Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology) pipeline (version 1.9.1)53. Merged sequences with 97% similarity were clustered into OTUs by UCLUST54, and representative sequences of OTUs were used to assign bacterial taxa from the RDP database55. Sequences assigned to mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are considered eukaryotic DNA sequences, were discarded. The Chao1 index was used to calculate α-diversity, weighted UniFrac distance matrices were used to calculate β-diversity, and PCoA with QIIME script (alpha_diversity.py, beta_diversity.py) was used to visualize results. Statistical significance of treatment differences was determined by analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) with 999 permutations.

Functional prediction

To predict inferred metagenome functions from the 16S rRNA gene sequences, PICRUSt analysis was used56. OTUs with 97% similarity were selected and taxonomically assigned. OTUs corresponding to chloroplasts and mitochondria were removed from the OTUs normalized by copy number. KEGG pathways were analysed at level three and normalized to the total of predicted pathways of each sample. Among the 328 pathways, 93 that are considered to be associated with metabolism were selected.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Time course differences were analysed with two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Two-group or four-group comparisons were conducted using a t test and one-way ANOVA. Area under the curve was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. To compare the specific OTU differences across Dapa and NaB treatment groups, LEfSe analysis was performed57. The threshold for the non-parametric factorial Kruskal–Wallis sum-rank test was α = 0.05. The threshold for the logarithmic LDA score was 3.0. Spearman’s correlation analysis was applied to test the correlation between total fat gain and relative abundance of genera that were significantly different in mice faecal microbiota in the four treatment groups. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (v. 5.0; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and R software (v. 3.3.2; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). To find statistically significant functions across the butyrate treatment, t-test was conducted and local FDR that calculated with respect to a single value was estimated58. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ng, M. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384, 766–781, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 (2014).

Wang, Y. C., McPherson, K., Marsh, T., Gortmaker, S. L. & Brown, M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 378, 815–825, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3 (2011).

Phung, O. J., Scholle, J. M., Talwar, M. & Coleman, C. I. Effect of noninsulin antidiabetic drugs added to metformin therapy on glycemic control, weight gain, and hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. JAMA 303, 1410–1418, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.405 (2010).

Ferrannini, E. & Solini, A. SGLT2 inhibition in diabetes mellitus: rationale and clinical prospects. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8, 495–502, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.243 (2012).

Cai, X. et al. The Association Between the Dosage of SGLT2 Inhibitor and Weight Reduction in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26, 70–80, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22066 (2018).

Devenny, J. J. et al. Weight loss induced by chronic dapagliflozin treatment is attenuated by compensatory hyperphagia in diet-induced obese (DIO) rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20, 1645–1652, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.59 (2012).

Ji, W. et al. Effects of canagliflozin on weight loss in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. PLoS One 12, e0179960, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179960 (2017).

Ferrannini, G. et al. Energy Balance After Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibition. Diabetes Care 38, 1730–1735, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-0355 (2015).

Arafat, A. M. et al. Glucagon increases circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 independently of endogenous insulin levels: a novel mechanism of glucagon-stimulated lipolysis? Diabetologia 56, 588–597, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2803-y (2013).

Taggart, A. K. et al. (D)-beta-Hydroxybutyrate inhibits adipocyte lipolysis via the nicotinic acid receptor PUMA-G. J Biol Chem 280, 26649–26652, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C500213200 (2005).

Kasubuchi, M., Hasegawa, S., Hiramatsu, T., Ichimura, A. & Kimura, I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients 7, 2839–2849, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7042839 (2015).

Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11450 (2012).

Rumberger, J. M., Arch, J. R. & Green, A. Butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids increase the rate of lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. PeerJ 2, e611, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.611 (2014).

Reigstad, C. S. et al. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J 29, 1395–1403, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.14-259598 (2015).

Sumara, G., Sumara, O., Kim, J. K. & Karsenty, G. Gut-derived serotonin is a multifunctional determinant to fasting adaptation. Cell Metab 16, 588–600, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.014 (2012).

Gao, Z. et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 58, 1509–1517, https://doi.org/10.2337/db08-1637 (2009).

den Besten, G. et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Protect Against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity via a PPARgamma-Dependent Switch From Lipogenesis to Fat Oxidation. Diabetes 64, 2398–2408, https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-1213 (2015).

De Vadder, F. et al. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell 156, 84–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016 (2014).

Canfora, E. E., Jocken, J. W. & Blaak, E. E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 577–591, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2015.128 (2015).

Merovci, A. et al. Dapagliflozin improves muscle insulin sensitivity but enhances endogenous glucose production. J Clin Invest 124, 509–514, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI70704 (2014).

Ferrannini, E. et al. Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest 124, 499–508, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI72227 (2014).

Hotta, Y. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates lipolysis in white adipose tissue but is not required for ketogenesis and triglyceride clearance in liver. Endocrinology 150, 4625–4633, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2009-0119 (2009).

Arner, P., Andersson, D. P., Backdahl, J. & Dahlman, I. & Ryden, M. Weight Gain and Impaired Glucose Metabolism in Women Are Predicted by Inefficient Subcutaneous Fat Cell Lipolysis. Cell Metab 28, 45–54 e43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.004 (2018).

Hondares, E. et al. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 286, 12983–12990, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.215889 (2011).

Habegger, K. M. et al. The metabolic actions of glucagon revisited. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 6, 689–697, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2010.187 (2010).

Lutz, T. A. & Woods, S. C. Overview of animal models of obesity. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 5, Unit5 61, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471141755.ph0561s58 (2012).

Vidrine, K. et al. Resistant starch from high amylose maize (HAM-RS2) and dietary butyrate reduce abdominal fat by a different apparent mechanism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 344–348, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20501 (2014).

Xu, Y. H. et al. Sodium butyrate supplementation ameliorates diabetic inflammation in db/db mice. J Endocrinol 238, 231–244, https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-18-0137 (2018).

Arpaia, N. et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504, 451–455, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12726 (2013).

Chang, P. V., Hao, L., Offermanns, S. & Medzhitov, R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 2247–2252, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1322269111 (2014).

Zhang, C. et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota in life-long calorie-restricted mice. Nat Commun 4, 2163, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3163 (2013).

Chelakkot, C., Ghim, J. & Ryu, S. H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp Mol Med 50, 103, https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0126-x (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Butyrate reduces appetite and activates brown adipose tissue via the gut-brain neural circuit. Gut 67, 1269–1279, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314050 (2018).

Duncan, S. H. et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, 1720–1724, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.155 (2008).

Walters, W. A., Xu, Z. & Knight, R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD. FEBS Lett 588, 4223–4233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.039 (2014).

Rosenbaum, M., Knight, R. & Leibel, R. L. The gut microbiota in human energy homeostasis and obesity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 26, 493–501, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2015.07.002 (2015).

Lee, H. & Ko, G. Effect of metformin on metabolic improvement and gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 5935–5943, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01357-14 (2014).

Zhang, Q. et al. Vildagliptin increases butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut of diabetic rats. PLoS One 12, e0184735, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184735 (2017).

Kang, Y. et al. Konjaku flour reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Int J Obes (Lond), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0187-x (2018).

Le Chatelier, E. et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 500, 541–546, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12506 (2013).

Zeng, Q. et al. Discrepant gut microbiota markers for the classification of obesity-related metabolic abnormalities. Scientific reports 9, 13424, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49462-w (2019).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12820 (2014).

Daniel, H. et al. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. The ISME journal 8, 295–308, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.155 (2014).

Yun, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of gut microbiota associated with body mass index in a large Korean cohort. BMC microbiology 17, 151, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1052-0 (2017).

Del Chierico, F. et al. Gut Microbiota Markers in Obese Adolescent and Adult Patients: Age-Dependent Differential Patterns. Front Microbiol 9, 1210, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01210 (2018).

Zaibi, M. S. et al. Roles of GPR41 and GPR43 in leptin secretory responses of murine adipocytes to short chain fatty acids. FEBS Lett 584, 2381–2386, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.027 (2010).

Lin, H. V. et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS One 7, e35240, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035240 (2012).

Terami, N. et al. Long-term treatment with the sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, ameliorates glucose homeostasis and diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. PLoS One 9, e100777, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100777 (2014).

Terasaki, M. et al. Amelioration of Hyperglycemia with a Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor Prevents Macrophage-Driven Atherosclerosis through Macrophage Foam Cell Formation Suppression in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetic Mice. PLoS One 10, e0143396, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143396 (2015).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Lee, Y. K. et al. Perilipin 3 Deficiency Stimulates Thermogenic Beige Adipocytes Through PPARalpha Activation. Diabetes 67, 791–804, https://doi.org/10.2337/db17-0983 (2018).

Eren, A. M., Vineis, J. H., Morrison, H. G. & Sogin, M. L. A filtering method to generate high quality short reads using illumina paired-end technology. PloS one 8, e66643, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066643 (2013).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7, 335–336, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (2010).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 5261–5267, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00062-07 (2007).

Langille, M. G. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol 31, 814–821, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2676 (2013).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12, R60, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 (2011).

Noble, W. S. How does multiple testing correction work? Nat Biotechnol 27, 1135–1137, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1209-1135 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Diabetes Association (2015F-5) and the SNUBH Research Fund (14-2017-011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.O. designed research studies, analyzed data, and wrote and edited the manuscript. W.J.S. and H.N.O. analysed the microbiota data and wrote and edited the manuscript. Y.L. and H.L.L. performed experiments and acquired and analyzed data. S.H.C., K.S.P., and H.C.J. designed research studies, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, T.J., Sul, W.J., Oh, H.N. et al. Butyrate attenuated fat gain through gut microbiota modulation in db/db mice following dapagliflozin treatment. Sci Rep 9, 20300 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56684-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56684-5

This article is cited by

-

Dapagliflozin ameliorates diabetes-induced spermatogenic dysfunction by modulating the adenosine metabolism along the gut microbiota-testis axis

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Consumption of yacon flour and energy-restricted diet increased the relative abundance of intestinal bacteria in obese adults

Brazilian Journal of Microbiology (2023)

-

Colonic expression of calcium transporter TRPV6 is regulated by dietary sodium butyrate

Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology (2022)

-

A bridge for short-chain fatty acids to affect inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease positively: by changing gut barrier

European Journal of Nutrition (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.