Abstract

Delayed or induced hatching in response to predation risk has been reported mainly in aquatic systems, where waterborne cues from predators and injured neighbouring eggs are available. Newly emerged larvae of the terrestrial predatory mite Neoseiulus womersleyi are vulnerable to predation by con- and heterospecific predatory mites, whereas their eggs are not. We examined whether N. womersleyi embryos delay hatching in response to artificial mechanical stimuli that simulates egg predation attempts. When embryos near the hatching stage were artificially stimulated every 5 min for 60 min, most stopped hatching for the duration of the 60-min period, whereas unstimulated embryos did not. Stimulated embryos resumed hatching when the treatment was stopped, and the proportion of hatched stimulated embryos caught up with that of unstimulated embryos within 120 min after stimuli stopped. Since hatching did not stop in response to changes in gravity direction, the effect of direct mechanical stimuli on the eggs was considered a proximate factor in delayed hatching. These results suggest that N. womersleyi embryos recognise immediate predation risk via mechanical stimuli, and delay hatching until the predation risk is reduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although animals in quiescent stages cannot avoid immediate biotic risks by moving, they can avoid risks by regulating their advance toward the next developmental stages. The embryos of some aquatic animals can either induce hatching in response to egg predators1,2 or delay hatching in response to hatchling predators3,4,5. In such aquatic systems, water-borne chemical cues emanating from predators and/or injured conspecific eggs in the same clutch are thought to be primal proximate factors affecting induced/delayed hatching2,3,4,5. Although such induced/delayed hatching in response to predator cues has yet been reported in arthropods including mites, some insect embryos synchronise hatching in response to vibrations produced by their mothers6,7 or siblings8, demonstrating the potential of arthropod embryos to detect and respond to mechanical stimuli.

Terrestrial predatory mites usually feed on prey such as spider mites, whiteflies and thrips; however, they also predate juveniles of con- and heterospecific predatory mites when there is a low density of prey mites9. Predatory mite larvae are generally vulnerable to intraguild predation immediately after hatching, whereas eggs are not10 because many predatory mite species penetrate the egg chorion with difficulty9. The predatory mite Neoseiulus womersleyi oviposits solitary eggs on abaxial leaf surfaces. Although N. womersleyi adults and nymphs attempt to attack conspecific eggs (Supplemental Fig. 1), they usually fail to pierce the eggs, resulting in mechanical stimuli such as egg shaking and rolling (hereafter predation attempts), which typically last several seconds (Yano, personal observation). If the embryos can perceive and distinguish these stimuli from others, then delaying hatching for the duration of the stimuli might prevent subsequent predation after hatching.

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that arthropod embryos delay hatching in response to mechanical stimuli simulating predation attempts by egg predators, and discuss how predatory mite embryos cope with immediate predation risks.

Materials and Methods

Mites

The N. womersleyi study population was collected from bushkiller plants Cayratia japonica (Thunb.) Gagnep. on the campus of Kyoto University in 2014 and reared on kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) leaf disks pressed onto water-saturated cotton in Petri dishes (diameter, 90 mm; depth, 14 mm). Leaf disks were heavily infested with the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae Koch as prey. We placed the leaf disks in transparent plastic containers maintained at 25 °C and 50% relative humidity under a 16-h light, 8-h dark (L16:D8) photoperiod. All experiments were conducted under these conditions.

Predation on conspecific eggs/larvae

To confirm that N. womersleyi eggs were less preyed upon than larvae, we randomly selected either five eggs (n = 12) or five 0-day-old larvae (n = 12) from the study population. We confined these individuals in a closed space (diameter, 18 mm; height, 5 mm, Fig. 1a) with water and air supplies according to the method of Ogawa and Osakabe11, together with a separately raised starved (thin) adult female N. womersleyi. To promote predation, we used starved females. Eggs were separately placed within the cage. We did not supply larvae with any food because they do not feed during the larval period12. After 24 h, the numbers of consumed eggs or larvae were recorded, and proportions of consumed eggs and larvae were compared using a Mann-Whitney U-test (SAS 9.22; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Predation attempts on conspecific eggs

To confirm egg predation attempts by conspecific adult females and describe their frequency, we controlled the hunger levels of the females by isolating them for either 1 (n = 23) or 4 (n = 21) days in 1.5-mL microtubes (Bioramo Microtube, As One, Osaka, Japan) with a water droplet. We introduced five eggs (one in the middle and four at even intervals near the periphery) on each 10-mm-diameter leaf circle. We then introduced a starved female onto the circle and observed the number and duration of predation attempts within 10 min. Attempts that lasted for more than 1 s were recorded. Numbers and total duration (s) of predation attempts were compared between females that had been starved for 1 and 4 days using a Mann-Whitney U-test (SAS 9.22).

Hatching in response to mechanical stimuli

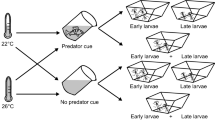

We explored whether simulated egg predation attempts could affect embryo hatching as follows. To obtain ready-to-hatch embryos, we prepared cohorts of N. womersleyi eggs. This process was necessary due to the extreme difficulty of screening embryos just before hatching without careful examination from all directions (i.e., stimulation). We prepared two egg cohorts (n = 62, 61) by collecting eggs oviposited by 240 adult female N. womersleyi within 3 h. We transferred these to one half of one side of each new leaf disk. After 2 days, when 30% of the embryos in each cohort had hatched (i.e., remaining embryos were thought to be nearly hatching), we transferred half of the remaining eggs to symmetrical positions (i.e., the other half) on the leaf disks using a fine brush and manipulated them as described below.

Due to the low frequency of egg predation attempts by starved adult females (less than once per egg within 10 min), we artificially simulated mechanical stimuli that occur during egg predation attempts instead of using actual predators. To simulate immediate predation risk, we stimulated individual eggs by rolling them ca. 90° around their longer diameter with a fine brush every 5 min for 60 min (stimulated eggs, n = 35). We could not stimulate eggs more frequently because each simulated predation attempt involving all 35 eggs required nearly 5 min to complete. The eggs remaining on the other side of the leaf served as a control group (n = 39). We recorded the number of hatched embryos every 15 min until 120 min after the stimulation treatment when the proportion of hatched embryos caught up with that of unstimulated embryos, and removed hatched larvae from among both stimulated and control eggs. Data from two cohorts were pooled for analysis. We compared the proportion of hatched embryos between the stimulated and control eggs at the end of the treatment period (60 min) and again at the end of the experiment (180 min) using Fisher’s exact test (SAS 9.22).

Hatching in response to changes in gravity direction

We explored whether relative changes in the direction of gravity can affect embryo hatching. This experiment was intended to simulate physical stimuli other than predation attempts. We prepared eggs near the hatching stage in the manner described above and transferred them onto a 20 × 20-mm leaf square pressed onto water-saturated cotton in a square dish (36 × 36 mm; depth, 14 mm). The dish was placed on its side to keep the leaf surface perpendicular; the eggs did not fall off because their surfaces are sticky (Fig. 1b). To change the relative gravity direction, the dish was turned upside down every 5 min for 60 min (gravity inversion, n = 72). Eggs on a fixed perpendicular dish served as a control group (n = 76). We observed the number of hatched embryos on perpendicular leaf surfaces every 15 min using a magnifying lens, and compared the proportion of hatched embryos between treatment and control eggs at the end of the experiment (60 min) using Fisher’s exact test (SAS 9.22).

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Predation on conspecific eggs/larvae

The mean ± SE proportion of N. womersleyi eggs preyed upon by a conspecific adult female was 3.33 ± 2.24% (n = 12), whereas that of larvae was 31.30 ± 6.45% (n = 12). These proportions differed significantly (P = 0.003, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fig. 2).

Predation attempts on conspecific eggs

The number of predation attempts on five eggs within 10 min differed significantly between females that had been starved for 1 and 4 days (P < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fig. 3a). The total duration (s) of predation attempts within 10 min also differed significantly between these groups (P < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fig. 3b). The maximum duration of predation attempts was 114 s, by a female starved for 4 days.

Predation attempts on conspecific eggs. The number of predation attempts by a starved adult female on five conspecific eggs within 10 minutes differed significantly between females that had been starved for 1 and 4 days (P < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fig. 3a). The total duration (seconds) of predation attempts also differed significantly (P < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fig. 3b).

Hatching in response to mechanical stimuli

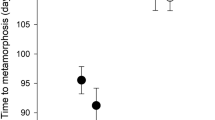

Most stimulated embryos did not hatch during the treatment period (i.e., initial 60 min), and the proportions of hatched embryos at the end of the treatment period (60 min) differed significantly between stimulated and control eggs (P = 0.0004, Fisher’s exact test, Fig. 4). However, stimulated embryos resumed hatching after the treatment was stopped, and the proportion of hatched embryos caught up with that of unstimulated embryos in the subsequent 120 min (P = 0.28, Fisher’s exact test).

Hatching in response to changes in gravity direction

The proportions of hatched embryos at the end of the gravity inversion experiment (60 min) did not differ significantly between the treatment and control eggs (P = 0.80, Fisher’s exact test, Fig. 5).

Discussion

We demonstrated that nearly hatching embryos of predatory mites delayed hatching in response to periodic mechanical stimuli that simulated predation attempts by con- or heterospecific predatory mites. Stimulated embryos resumed hatching after treatment was stopped, clearly indicating that the lower hatching rate observed during treatment was not due to lethal damage caused by the treatment. We also demonstrated that the embryos did not stop hatching in response to changes in gravity direction, which can be caused by natural disturbances such as the wind shaking eggs on leaves. Such disturbances change the direction that gravity acts on the eggs without touching the eggs. Therefore, embryo hatching may cease in response to direct mechanical stimuli or changes in the egg part contacting the leaf surface as a result of such stimuli, likely as an adaptation against predation attempts by predatory mites. Egg predation attempts by conspecifics did occur under experimental conditions, but their frequency seemed to depend on predator conditions. We also demonstrated that eggs are safer than larvae in the presence of conspecific adults. As predatory mite eggs are generally better protected against such predators than are larvae just after hatching9,10, eggs under immediate predation risks remain safer if the egg stage is prolonged. We therefore hypothesised that predatory mite embryos delay their hatching in response to an immediate predation risk until the risk is reduced. Because predation attempts on N. womersleyi eggs by conspecifics lasted for a few minutes at most, the ability of embryos to delay hatching by at least 60 min seems sufficient to mitigate predation risk. Interestingly, stimulated embryos did not hatch immediately after simulated stimuli were stopped, but seemed to hatch gradually over time. This cautious embryo hatching after the stimuli ended may reflect an ‘arms race’ between eggs and predatory mites that might not move away, but rather wait near the eggs for larvae to hatch9,13.

We demonstrated that mechanical stimuli alone can delay hatching in predatory mite embryos. Induced hatching in response to mechanical vibration has been reported in egg masses of a wide range of animals including reptiles14 and insects6,7,8; however, this study is the first report of delayed hatching in response to predator-induced mechanical stimuli. Although it is possible that contact and/or airborne chemical cues from predators may also affect the hatching timing of predatory mite embryos, we speculate that these cues are less important for the following reasons. First, the mites do not oviposit in clusters; we preliminarily observed that none of 32 eggs oviposited on a leaf by 15 females within 24 h were in contact with one another. Therefore, chemical cues from predators attacking nearby conspecific eggs would likely be rare. Second, unlike water-borne chemical cues that affect embryo hatching in aquatic animals2,3,4,5, airborne chemical cues from a distance appear barely detectable by some predatory mites15,16. In contrast, direct mechanical stimuli on eggs, which are generally well defended against predators, may be primary cues of immediate predation risks, as only eggs under attack receive these stimuli. In addition, embryos may respond to non-specific mechanical stimuli because they are typically attacked by both con- and heterospecific predatory mites17, which may possess different forms of contact and/or volatile chemicals.

We hypothesise that delayed embryo hatching in response to predator-induced mechanical stimuli may be widespread in solitary eggs that are robustly defended against predation and in systems in which chemical predation cues are difficult to detect. This hypothesis should be addressed in future studies, especially for arthropods inhabiting terrestrial systems.

Data Availability

All data can be found in the Supplementary Material.

References

Warkentin, K. M. Adaptive plasticity in hatching age: A response to predation risk trade-offs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3507–3510, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.8.3507 (1995).

Chivers, D. P. et al. Predator-induced life history changes in amphibians: egg predation induces hatching. Oikos 92, 135–142, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.920116.x (2001).

Sih, A. & Moore, R. D. Delayed hatching of salamander eggs in response to enhanced larval predation risk. Am. Nat. 142, 947–960, https://doi.org/10.1086/285583 (1993).

Jones, M., Laurila, A., Peuhkuri, N., Piironen, J. & Seppa, T. Timing an ontogenetic niche shift: responses of emerging salmon alevins to chemical cues from predators and competitors. Oikos 102, 155–163, https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12347.x (2003).

Miner, B. G., Donovan, D. A. & Andrews, K. E. Should I stay or should I go: predator- and conspecific-induced hatching in a marine snail. Oecologia 163, 69–78, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-010-1570-z (2010).

Mukai, H., Hironaka, M., Tojo, S. & Nomakuchi, S. Maternal vibration induces synchronous hatching in a subsocial burrower bug. Anim. Behav. 84, 1443–1448, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.09.012 (2012).

Mukai, H., Hironaka, M., Tojo, S. & Nomakuchi, S. Maternal vibration: an important cue for embryo hatching in a subsocial shield bug. PLos One 9, e87932, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087932 (2014).

Endo, J., Takanashi, T., Mukai, H. & Numata, H. Egg-cracking vibration as a cue for stink bug siblings to synchronize hatching. Curr. Biol. 29, 143–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.024 (2019).

Schausberger, P. Cannibalism among phytoseiid mites: a review. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 29, 173–191, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:102583920 (2003).

Faraj, F., Janssen, A. & Sabelis, M. W. The benefits of clustering eggs: the role of egg predation and larval cannibalism in a predatory mite. Oecologia 131, 20–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-001-0846-8 (2002).

Ogawa, Y. & Osakabe, M. Development, long-term survival, and the maintenance of fertility in Neoseiulus californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae) reared on an artificial diet. Exp. Appl. Acaol. 45, 123–136, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-008-9189-z (2008).

Chittenden, A. R. & Saito, Y. Why are there feeding and nonfeeding larvae in phytoseiid mites (Acari, Phytoseiidae)? J. Ethol. 19, 55–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/s101640170018 (2001).

Walzer, A., Blümel, S. & Schausberger, P. Population dynamics of interacting predatory mites, Phytoseiulus persimilis and Neoseiulus californicus, held on detached bean leaves. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 25, 731–743, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016332129137 (2001).

Doody, J. S., Stewart, B., Camacho, C. & Christian, K. Good vibrations? Sibling embryos expedite hatching in a turtle. Anim. Behav. 83, 645–651, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.12.006 (2012).

Zemek, R., Nackman, G. & Ruzickova, S. How does Phytoseiulus persimilis find its prey when foraging within a beab plant? In: Bertrand, M., Kreiter, S., McCoy, K. D., Migeon, A., Navajas, M., Tixier, M.-S. & Vial, L. (eds) Integrative acarology. Proceedings of the 6th European congress. European Association of Acarologists, 2008, pp 390–393 (2008).

Yano, S. & Osakabe, M. Do spider mite-infested plants and spider mite trails attract predatory mites? Ecol. Res. 24, 1173–1178, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-009-0598-1 (2009).

Gotoh, T. et al. Factors determining species displacement of related predatory mite species (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 63, 205–215, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-014-9769-z (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant Number 15K07792 to S.Y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. conceived the study. K.F. and S.Y. conducted experiments. K.F. and S.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuse, K., Yano, S. Delayed mite hatching in response to mechanical stimuli simulating egg predation attempts. Sci Rep 9, 13395 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50007-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50007-4

This article is cited by

-

Spider mites avoid caterpillar traces to prevent intraguild predation

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.