Abstract

This study evaluated the efficiency of the removal of heavy metals from contaminated water via adsorption isotherm and kinetic experiments on two composite mineral adsorbents, CMA1 and CMA2. The developed CMA1 (zeolite with clinoptilolite of over 20 weight percent and feldspar of ~10 percent, with Portland cement) and CMA2 (zeolite with feldspar of over 15 weight percent and ~9 percent clinoptilolite, with Portland cement) were applied to remove Cu, Cd, and Pb ions. Based on the adsorption isotherm and kinetic experiments, the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 exhibited high removal efficiency for Cu, Cd, and Pb ions in solution compared to other adsorbents. In the adsorption kinetic experiment, CMA2 demonstrated better adsorption than CMA1 with the same initial concentration and reaction time, and Cu, Cd, and Pb ions almost reached equilibrium within 180 min for both CMA1 and CMA2. The results of the adsorption kinetic experiments with pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models indicated that the PSO model was more suitable than the PFO model. Comparing the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models, the former showed a very slightly higher correlation coefficient (r2) than the latter, indicating that the two models can both be applied to heavy metal solutions on a spherical monolayer surface with a weak heterogeneity of the surface. Additionally, the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 demonstrated different removal abilities depending on which heavy metals were used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Substantial research has been conducted in the past 20 years on which materials are best for adsorbing heavy metals (Table 1). Garcıa-Sánchez et al.1 evaluated the heavy-metal adsorption capacity of clay minerals (sepiolite, palygorskite, and bentonite) from different mineral deposits with a reduction in metal mobility and bioavailability for remediation of polluted soils in the Guadiamar Valley. Erdem et al.2 studied the adsorption behaviour of natural clinoptilolite with respect to Co, Cu, Zn, and Mn ions and found that the adsorption was dependent on charge density and hydrated ion diameter, showing great potential for natural clinoptilolite to remove cationic heavy metal species from industrial wastewater. Ok et al.3 studied a mixture of zeolite and Portland cement (ZeoAds) as a substitute for activated carbon and tested its efficiency for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions for wastewater treatment. Park and Hwang4 used adsorption tests to evaluate feldspar porphyry as an adsorbent for heavy metals in natural water. Nguyen et al.5 determined the adsorption behaviours of Cd, Cu, Cr, Pb, and Zn individually and collectively on an Australian natural zeolite with an iron coating (ICZ). He et al.6 carried out isotherms and kinetics studies using a synthesized zeolite from fly ash to investigate the adsorption capacity of heavy metal ions (Pb, Cu, Cd, Ni, and Mn) in aqueous solutions. Taamneh and Sharadqah7 evaluated the use of natural Jordanian zeolite (NJ zeolite) as a practical adsorbent for removing Cd and Cu ions. Lee et al.8 evaluated the adsorption performance of valuable metal ions (Cu, Co, Mn, and Zn) using a synthesized zeolite (Z-C2) from fly ash.

Various researchers9,10,11,12,13 have characterized the chemical, surface, and ion-exchange properties of clinoptilolite. Zamzow et al.11 studied the inorganic cation exchange capacity of clinoptilolite and the selectivity series as follows: Pb2+ > Cd2+ > Cs+ > Cu2+ > Co2+ > Cr3+ > Zn2+ > Ni2+ > Hg2+. Jama and Yücel10 recognized a very high preference of clinoptilolite for ammonium ions over sodium and calcium ions but not over potassium ions. Mier et al.12 identified the interactions of Pb2+, Cd2+, and Cr3+ competing for ion-exchange sites in natural clinoptilolite. Regarding the ion exchange of Pb2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, and Cr3+ on natural clinoptilolite, Inglezakis et al.13 found that equilibrium is favourable for Pb2+, unfavourable for Cu2+, and of sigmoidal shape for Cr3+ and Fe3+. Since commercial clinoptilolite is relatively costly, mixtures of zeolite and other less expensive organic and inorganic materials, such as cement, clays, and polymers, have been formulated for specific pollutants14.

Recently, functionalized adsorbents such as nanocomposite materials have been prepared for harmful heavy metal ions and organic compound adsorption and have been used for diverse applications15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Moreover, natural mineral-modified absorbents have the advantage that they can be applied not only to the aqueous phase but also to the soil phase24,25,26,27,28,29. This study aimed to reveal the efficiency of the removal of heavy metals by applying modified natural minerals as adsorbents to contaminated groundwater. For this purpose, we evaluated the cation adsorption performance and adsorption equilibrium characteristics of the composite mineral adsorbents CMA1 (zeolite with clinoptilolite of over 20 weight percent and feldspar of ~10 percent, with Portland cement) and CMA2 (zeolite with feldspar of over 15 weight percent and ~9 percent of clinoptilolite, with Portland cement) through adsorption isotherms and kinetics. Specifically, we looked at how CMA1 and CMA2 performed in the removal of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions from polluted water.

Materials and Methods

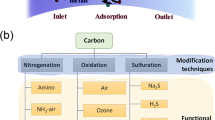

Preparation and characterization of the adsorbents

The preparation procedure of the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 is illustrated in Fig. 1. All experiments were conducted in a 10-L polyethylene reactor equipped with a stirrer. To prepare the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2, clinoptilolite-rich zeolite, slightly weathered feldspars showing a porous structure under a microscope, and normal Portland cement were prepared. Porous feldspar was prepared from weathered feldspar porphyry that was pulverized into 44-µm particles after being heated at 480 °C for 20 min. For the CMA1 adsorbent, a mixture of clinoptilolite-rich zeolite (C) and Portland cement (PC) at a ratio of C:PC = 70:30 wt% was cured for 28 days after adding water and lightweight foam. Finally, the CMA1 adsorbent powder was made by crushing the cured specimen. For the CMA2 adsorbent, a mixture of clinoptilolite-rich zeolite (C), porous feldspar (PF), and Portland cement (PC) at a ratio of C:PF:PC = 40:30:30 wt% was cured for 28 days after adding water and lightweight foam. Eventually, the CMA2 adsorbent powder was produced by crushing the cured specimen.

Crystallization and chemical characterization were performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Philips X’Pert-MPD System). XRD patterns of the samples were scanned on a powder diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) at a diffraction angle of 2θ in the range of 5–50° in 0.02° steps (3 s per step). The crystal morphologies of the samples were analysed by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4200), with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a magnification of 20,000 times. The samples were coated with a thin layer of platinum and mounted on a copper slab using double-sided tape for the SEM analysis.

Methodology

Batch tests were performed for adsorption isotherm and adsorption kinetic experiments using the two adsorbents (CMA1 and CMA2) and standard heavy metal (Cu, Cd, and Pb ions) solutions for the different ion adsorption performance and adsorption equilibrium characteristics. The adsorption isotherm and kinetic experiments were conducted to determine the adsorption characteristics and adsorption rate, respectively, of the heavy metal ions. Fifty millilitres of Cu, Cd, and Pb ion solutions and 0.05 g of CMA1 and CMA2 were placed in a 50-mL conical centrifuge tube (Falcon, 352070) and stirred at 200 rpm using a horizontal shaker (Vision, VS-8480S). For the adsorption kinetic experiment, 0.05 g of the adsorbent was added and stirred with 50 mL of a 1,000 mg/L heavy metal solution, and the residual concentration was analysed at reaction times of 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 360, and 480 min. For the adsorption isotherm experiment, 0.05 g of the adsorbent was added to 50 mL of 50–1,000 mg/L heavy metal solution with stirring, and the residual concentration was analysed after 24 h of reaction time. The pH change experiments were conducted with 1,000 mg/L Cu, Cd, and Pb ion solutions at 25 °C. The initial pH in the solutions was adjusted to 3.0, 5.0, or 7.0 by adding 0.5 M HNO3 or 0.5 M NaOH solution. The pH values were measured using a pH meter (Istek AJ-7724, Korea).

Samples were taken at regular intervals and centrifuged (Vision Scientific VS-5000i2, Korea) for 3 min at 3,000 rpm. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered, and the Cu, Cd, and Pb ion concentrations were analysed by using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 100, Germany).

Theory

Adsorption kinetics

The pseudo-first-order (PFO) rate equation for the adsorption kinetics of solutes from a liquid solution that was proposed by Lagergren30 is:

where q and qe are the amounts of solute adsorbed (mg) per adsorbent (g) at any time and at equilibrium, respectively, and k1 is the PFO rate constant of adsorption. Integrating Eq. (1) for the boundary conditions t = 0 to t and q = 0 to q gives:

The pseudo-second-order (PSO) rate equation for the adsorption kinetics of solutes from a liquid solution proposed by Ho and McKay31 is:

The integration of Eq. (3) for the boundary conditions t = 0 to t and q = 0 to q gives:

where k2 is the PSO rate constant of adsorption. A linear equation can then be obtained from Eq. (4):

The plot of t/q versus t gives a straight line with a slope of 1/qe and an intercept of 1/k2qe2, and then qe and k2 can be evaluated from the slope and intercept, respectively.

Adsorption isotherms

According to the formula by Vanderborght and Van Griekenm32, Q, the solute adsorbed (mg) per adsorbent (g), is

where V is the volume of the adsorbate (L), Ci is the initial concentration of adsorbate (mg/L), Ce is the concentration of the adsorbate after adsorption (mg/L), and W is the weight of the adsorbent (g). The experimentally derived isotherm can be fitted into the Langmuir33 and Freundlich34 adsorption isotherms, which represent, respectively, uniform adsorption energy onto the surface with no transmigration of adsorbate in the plane of the surface and the adsorption on a heterogeneous surface. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm is valid for monolayer adsorption onto a surface that contains a finite number of identical sites. The removal efficiency expressed as the percent of sorption is:

According to Langmuir, the amount adsorbed, Qe (mg/g), is defined as:

where Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L), Qm is the Langmuir constant related to the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g), and KL is the Langmuir isotherm coefficient related to the affinity of the sorbate for the binding sites. Equation (8) can be re-arranged into a linear form:

Using the Freundlich equation, the amount absorbed, Qe (mg/g), is:

Thus, linearizing Eq. (10),

where KF is the Freundlich isotherm coefficient or an approximate indicator of the adsorption capacity (mg/g), 1/n is a function of the strength of the adsorption in the adsorption process, and n is the adsorption intensity35. A value of n = 1 indicates that the partition between the two phases is independent of the concentration, n > 1 indicates normal adsorption, and n < 1 indicates cooperative adsorption36. A value of 1 < n < 10 demonstrates a favourable sorption process37. The constant change of KF and n with an increase in temperature reflects the empirical observation that the quantity adsorbed rises more slowly, such that higher pressures are required to saturate the surface. For the determination of KF and n by data fitting, linear regression is generally used to determine the parameters of the kinetic and isotherm models38. The linear least-squares method and linearly transformed equations have been widely applied to correlate sorption data, where the smaller the 1/n (or heterogeneity parameter), the greater the expected heterogeneity.

Results

Characterization of the adsorbents

The composite mineral adsorbents, CMA1 and CMA2, are composed of clinoptilolite, feldspars, and Portland cement. XRD analysis showed that CMA1 and CMA2 consisted of albite, calcite, dachiardite, clinoptiloite, and mordenite (Fig. 2). Feldspar is reported to have a heavy metal adsorption capacity39,40,41. Clinoptilolite, with the chemical formula of (Na,K)64Al6Si30O72·nH2O, one of most abundant natural zeolites, is found in sedimentary rocks of volcanic origin and occurs with silicate minerals such as feldspar, quartz, other zeolites (members of the tectosilicates subclass), clays (members of the phyllosilicates subclass), and volcanic glass42. Clinoptilolite, along with heulandite and mordenite, has a high cation capacity43. Its tabular morphology shows an open reticular formation with easy access, formed by open channels of 8- to 10-membered rings. Feldspars, anhydrous aluminosilicates composed of potassium, sodium, and calcium, are structured by silicon and aluminium occupying the centres of the tetrahedrals of SiO4 and AlO4. These tetrahedrals are linked to other tetrahedrals at each corner, forming a 3-D, negatively charged framework. Potassium, sodium, and calcium within the voids of the structure can be exchanged with other cations. Portland cement is a very common solidification and stabilization material and is used as a supplement to clinoptilolite for adsorption purposes44. The SEM images of CMA1 and CMA2 presented amorphous porous particles, which are consistent with the aggregated forms of albite, calcite, dachiardite, clinoptiloite, and mordenite (Fig. 3). Overall, dachiardite, clinoptiloite, and mordenite can be considered major minerals involved in adsorption for heavy metal control45,46,47,48.

Effect of initial pH on Cu, Cd, and Pb ions

The adsorption of heavy metals is significantly influenced by the initial pH of the solution since the initial pH determines the surface charge of the adsorbent and the degree of speciation and ionization of the adsorbate49,50,51,52,53. The effects of the initial pH value were evaluated by the Cu, Cd, and Pb adsorption capacities in the solutions (Fig. 4). The adsorption capacities of Cu in the solutions were determined to be 71–107.5, 126–144.5, and 395.5–479.5 mg/g at initial pH values of 2.78, 4.94, and 6.50, respectively. The adsorption capacities of Cd in the solutions were 261–279, 302–311, and 198–222 mg/g at initial pH values of 2.80, 4.76, and 6.45, respectively. Additionally, the adsorption capacities of Pb in the solutions were determined to be 453.1–495.4, 570.2–594.6, and 613.8–646.5 mg/g at initial pH values of 2.83, 4.98, and 7.01, respectively. At pH < 5.0, Cu2+, Cd2+, and Pb2+ are the primary species in the Cu, Cd, and Pb solutions, respectively; the species vary with solution pH, and the adsorption of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions mainly involves divalent metal ions54,55,56. Based on the effect of the initial pH on Cu, Cd, and Pb ions, each of adsorption kinetic experiments was conducted at a pH value less than 5.0.

Adsorption kinetic experiments

To determine the equilibrium reaction time, the adsorption of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions on the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 were plotted as a function of reaction time in Fig. 5. At the same initial concentration and reaction time, the CMA2 demonstrated better adsorption than the CMA1 (Table 2). The Cu, Cd, and Pb ions adsorption on the CMA1 and CMA2 had almost reached equilibrium within 180 min.

PFO and PSO models were applied to the results of the adsorption kinetic experiments for Cu, Cd, and Pb ions on the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2. The PFO and PSO models demonstrated different determination coefficient (r2) values, between 0.7690–0.9515 and 0.9255–0.9977, respectively, indicating that the latter was more suitable than the former (Fig. 5). The adsorption capacities obtained from the experiments did not agree with the values estimated to reproduce the Cu, Cd, and Pb ions adsorption kinetics with the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 from the PFO model. However, the experimental results were similar to the values calculated from the PSO model, and the r2 values were also very close to unity. Therefore, Cu, Cd, and Pb ions adsorption by the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 could be more accurately explained by the PSO model than by the PFO model. Additionally, the adsorbent CMA2 was more effective in removing the heavy metals ions of Pb, Cd, and Cu than the CMA1, in decreasing order of their qe cal values.

Adsorption isotherm experiments

The adsorption isotherms for Cu, Cd, and Pb ions on the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 are plotted in Fig. 6. The isotherm parameters, Qe, KL, n, KF, and r2 obtained from the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms are given in Table 3. The results of the adsorption isotherm experiment for Cu, Cd, and Pb ions on the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 were interpreted by using the Langmuir and Freundlich models. Table 3 and Fig. 6 show that the Langmuir model gave a slightly higher correlation coefficient (r2) than the Freundlich model, indicating that the two models could both be applied to the heavy metal solutions on a spherical monolayer surface with a weak heterogeneity of the surface. The adsorption capacities of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions by the Langmuir model were 145.84–154.71 mg/g, 162.58–177.99 mg/g, and 802.23–932.08 mg/g, respectively, while the adsorption capacities of Cu and Cd ions by Erdem et al.2 and Ok et al.3 were 9.0–23.3 mg/g using clinoptilolite (natural zeolite) and ZeoAds (a mixture of zeolite and Portland cement).

The maximum adsorption capacities (Qm) of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions by using the Langmuir model were determined to be 802.23 mg/g (CMA1) and 932.08 mg/g (CMA2) for Pb, 177.99 mg/g (CMA1) and 162.58 mg/g (CMA2) for Cd, and 145.84 mg/g (CMA1) and 154.71 mg/g (CMA2) for Cu, after dosing the adsorbents with only 1 g/L of the heavy metal solution; and hence, these values are significantly higher than those of the existing adsorbents as presented in Table 1. By comparison, an absorption experiment using a highly porous composite material with immobilization of an organic ligand onto silica monoliths57 that was performed to efficiently remove Pb ions in wastewater resulted in a Qm of 204.34 mg/g, and an absorption experiment using a mesoporous composite material synthesized by the immobilization of an organic ligand onto mesoporous silica for effectively removing Cu ions in aqueous solution obtained a Qm of 197.15 mg/g58.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, the adsorption performance and adsorption equilibrium characteristics of the heavy metal ions were evaluated through adsorption isotherm and adsorption kinetic experiments. We applied the composite adsorbents CMA1 (zeolite with clinoptilolite of over 20 weight percent and feldspar of ~10 percent, with Portland cement) and CMA2 (zeolite with feldspar of over 15 weight percent and ~9 percent clinoptilolite, with Portland cement) to heavy metal (Cu, Cd, and Pb ions) solutions.

The adsorption kinetic experiments results showed that the adsorption of the heavy metal ions almost reached within 180 min. PFO and PSO models for Cu, Cd, and Pb ions on the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2 resulted in different r2 values of 0.7690–0.9515 and 0.9255–0.9977, respectively, indicating that the PSO model was more suitable than the PFO model. Furthermore, the adsorbent CMA2 was more effective in removing the heavy metal ions of Cu, Cd, and Pb than the CMA1, in decreasing order of their qe cal values.

The adsorption isotherm experiments showed that both the Langmuir model and the Freundlich model were applicable to the heavy metal solutions because the adsorbents had spherical monolayer surfaces with a weak heterogeneity of the surface. The maximum adsorption capacities of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions from the Langmuir model resulted were 802.23 mg/g (CMA1) and 932.08 mg/g (CMA2) for Pb, 177.99 mg/g (CMA1) and 162.58 mg/g (CMA2) for Cd, and 145.84 mg/g (CMA1) and 154.71 mg/g (CMA2) for Cu, dosing the adsorbents at only 1 g/L of the heavy metal solution. These maximum adsorption capacities were significantly higher than the maximum adsorption capacities of Cu, Cd, and Pb ions using other adsorbents, as presented in Table 1.

Furthermore, the adsorbent CMA2, including cost-effective natural feldspar, displayed better adsorption capacity than the CMA1. The results of this study can be applied to effectively remove heavy metal ions in contaminated water and wastewater since both absorbents (CMA1 and CMA2) showed excellent removal efficiency of heavy metal ions in solution. Future research will be focused on revealing the mechanism of the different performances on the heavy metal (Cu, Cd, and Pb) ions by the adsorbents CMA1 and CMA2, which is probably related to the feldspar content.

References

Garcıa-Sanchez, A., Alastuey, A. & Querol, X. Heavy metal adsorption by different minerals: application to the remediation of polluted soils. Sci. Total Environ. 242, 179–188 (1999).

Erdem, E., Karapinar, N. & Donat, R. The removal of heavy metal cations by natural zeolites. J Colloid Interface Sci 280, 309–314 (2004).

Ok, Y. S., Yang, J. E., Zhang, Y. S., Kim, S. J. & Chung, D. Y. Heavy metal adsorption by a formulated zeolite-Portland cement mixture. J. Hazard. Mater. 147, 91–96 (2007).

Park, S. B. & Hwang, J. Adsorption characteristics of altered feldspar porphyry for heavy metals. Journal of Korean Earth Science Society 29, 246–254 (2008).

Nguyen, T. C. et al. Simultaneous adsorption of Cd, Cr, Cu, Pb, and Zn by an iron-coated Australian zeolite in batch and fixed-bed column studies. Chem Eng J 270, 393–404 (2015).

He, K., Chen, Y., Tang, Z. & Hu, Y. Removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by zeolite synthesized from fly ash. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23, 2778–2788 (2016).

Taamneh, Y. & Sharadqah, S. The removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution using natural Jordanian zeolite. Appl Water Sci 7, 2021–2028 (2017).

Lee, C. H., Park, J. M. & Lee, M. G. Competitive adsorption in binary solution with different mole ratio of Sr and Cs by zeolite A: adsorption isotherm and kinetics. J. Environ. Sci. Int 24, 151–162 (2015).

Klute, A. Physical and mineralogical methods. Planning 8, 79 (1986).

Jama, M. A. & Yu¨cel, H. Equilibrium studies of sodium-ammonium, potassium-ammonium, and calcium-ammonium exchanges on clinoptilolite zeolite. Sep Sci Technol 24, 1393–1416 (1989).

Zamzow, M. J., Eichbaum, B. R., Sandgren, K. R. & Shanks, D. E. Removal of heavy metals and other cations from wastewater using zeolites. Sep Sci Technol 25, 1555–1569 (1990).

Mier, M. V., Callejas, R. L., Gehr, R., Cisneros, B. E. J. & Alvarez, P. J. Heavy metal removal with Mexican clinoptilolite: multi-component ionic exchange. Water Res. 35, 373–378 (2001).

Inglezakis, V. J., Loizidou, M. D. & Grigoropoulou, H. P. Equilibrium and kinetic ion ex- change studies of Pb2+, Cr3+, Fe3+ and Cu2+ on natural clinoptilolite. Water Res. 36, 2784–2792 (2002).

Noh, J. H. & Koh, S. M. Mineralogical characteristics and genetic environment of zeolitic bentonite in Yeongil area. J. Miner. Soc. Korea. 17, 135–145 (2004).

Awual, M. R. et al. Copper (II) ions capturing from water using ligand modified a new type mesoporous adsorbent. Chem Eng J. 221, 322–330 (2013a).

Awual, M. R. et al. Trace copper (II) ions detection and removal from water using novel ligand modified composite adsorbent. Chem Eng J. 222, 67–76 (2013b).

Awual, M. R. A novel facial composite adsorbent for enhanced copper (II) detection and removal from wastewater. Chem Eng J. 266, 368–375 (2015).

Awual, M. R. et al. Schiff based ligand containing nano-composite adsorbent for optical copper (II) ions removal from aqueous solutions. Chem Eng J. 279, 639–647 (2015).

Awual, M. R. Assessing of lead (III) capturing from contaminated wastewater using ligand doped conjugate adsorbent. Chem Eng J. 289, 65–73 (2016).

Awual, M. R., Hasan, M. M., Khaleque, M. A. & Sheikh, M. C. Treatment of copper (II) containing wastewater by a newly developed ligand based facial conjugate materials. Chem Eng J. 288, 368–376 (2016).

Awual, M. R. New type mesoporous conjugate material for selective optical copper (II) ions monitoring & removal from polluted waters. Chem Eng J. 307, 85–94 (2017).

Awual, M. R. et al. Efficient detection and adsorption of cadmium (II) ions using innovative nano-composite materials. Chem Eng J. 343, 118–127 (2018).

Shahat, A. et al. Large-pore diameter nano-adsorbent and its application for rapid lead (II) detection and removal from aqueous media. Chem Eng J. 273, 286–295 (2015).

Conca, J. L. & Wright, J. An Apatite II permeable reactive barrier to remediate groundwater containing Zn, Pb and Cd. Appl Geochem 21, 1288–1300 (2006).

Liu, Y., Mou, H., Chen, L., Mirza, Z. A. & Liu, L. Cr (VI)-contaminated groundwater remediation with simulated permeable reactive barrier (PRB) filled with natural pyrite as reactive material: environmental factors and effectiveness. J. Hazard. Mater. 298, 83–90 (2015).

Misaelides, P. Application of natural zeolites in environmental remediation: A short review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 144, 15–18 (2011).

Olu-Owolabi, B. I. et al. Fractal-like concepts for evaluation of toxic metals adsorption efficiency of feldspar-biomass composites. J Clean Prod 171, 884–891 (2018).

Wang, S. & Peng, Y. Natural zeolites as effective adsorbents in water and wastewater treatment. Chem Eng J. 156, 11–24 (2010).

Wantanaphong, J., Mooney, S. J. & Bailey, E. H. Natural and waste materials as metal sorbents in permeable reactive barriers (PRBs). Environ Chem Lett. 3, 19–23 (2005).

Lagergren, S. Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption geloster stoffe, Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens. Handlingar 24, 1–39 (1898).

Ho, Y. S. & McKay, G. The kinetics of sorption of basic dyes from aqueous solution by sphagnum moss peat. Can J Chem Eng 76, 822–827 (1998).

Vanderborght, B. M. & Grieken, R. E. V. Enrichment of trace metals in water by adsorption on activated carbon. Anal. Chem. 49, 311–316 (1977).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403 (1918).

Freundlich, H. Kapillarchemie, eine Darstellung der Chemie der Kolloide und verwandter Gebiete (von Dr. Herbert Freundlich, Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, 1909).

Voudrias, E., Fytianos, K. & Bozani, E. Sorption–desorption isotherms of dyes from aqueous solutions and wastewaters with different sorbent materials. Global Nest Int. J. 4, 75–83 (2002).

Mohan, S. V. & Karthikeyan, J. Removal of lignin and tannin colour from aqueous solution by adsorption onto activated charcoal. Environ. Pollut. 97, 183–187 (1997).

Goldberg, S. Equations and models describing adsorption processes in soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 8, 489–517 (2005).

Rosa, G. et al. Recycling poultry feathers for Pb removal from wastewater: kinetic and equilibrium studies. International Journal of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 1, 185–193 (2008).

Aşçı, Y., Nurbaş, M. & Açıkel, Y. S. A comparative study for the sorption of Cd (II) by K-feldspar and sepiolite as soil components, and the recovery of Cd (II) using rhamnolipid biosurfactant. J. Environ. Manage. 88, 383–392 (2008).

Ding, D. et al. U (VI) ion adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics from aqueous solution onto raw sodium feldspar and acid-activated sodium feldspar. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 299, 1903–1909 (2014).

Eba, F. et al. Treatment of aqueous solution of lead content by using natural mixture of kaolinite-albite-montmorillonite-illite clay. Journal of Applied Sciences 11, 2536–2545 (2011).

Tsitsishvili, G. V., Andronikashvili, T. G., Kirov, G. R. & Filizova, L. D. Natural Zeolites (Ellis Horwood, 1992).

Inglezakis, V. J. The concept of “capacity” in zeolite ion-exchange systems. J Colloid Interface Sci 281, 68–79 (2005).

Perraki, T., Kakali, G. & Kontoleon, F. The effect of natural zeolites on the early hydration of Portland cement. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 61, 205–212 (2003).

Huang, C. P. & Hao, O. J. Removal of some heavy metals by mordenite. Environ Technol 10, 863–874 (1989).

Rosales-Landeros, C., Barrera-Díaz, C. E., Bilyeu, B., Guerrero, V. V. & Núnez, F. U. A review on Cr (VI) adsorption using inorganic materials. Am J Analyt Chem 4, 8 (2013).

Seliman, A. F. & Borai, E. H. Utilization of natural chabazite and mordenite as a reactive barrier for immobilization of hazardous heavy metals. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 18, 1098–1107 (2011).

Wang, X. S. Equilibrium and Kinetic Analysis for Cu2+ and Ni2+ adsorption onto Na-Mordenite. The Open Environmental Pollution & Toxicology Journal 1, 107–111 (2009).

Awual, M. R., Rahman, I. M., Yaita, T., Khaleque, M. A. & Ferdows, M. pH dependent Cu (II) and Pd (II) ions detection and removal from aqueous media by an efficient mesoporous adsorbent. Chem Eng J. 236, 100–109 (2014).

Camacho, L. M., Deng, S. & Parra, R. R. Uranium removal from groundwater by natural clinoptilolite zeolite: effects of pH and initial feed concentration. J. Hazard. Mater. 175, 393–398 (2010).

Cho, H., Oh, D. & Kim, K. A study on removal characteristics of heavy metals from aqueous solution by fly ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 127, 187–195 (2005).

Glatstein, D. A. & Francisca, F. M. Influence of pH and ionic strength on Cd, Cu and Pb removal from water by adsorption in Na-bentonite. Appl Clay Sci 118, 61–67 (2015).

Kwon, J. S., Yun, S. T., Lee, J. H., Kim, S. O. & Jo, H. Y. Removal of divalent heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn) and arsenic (III) from aqueous solutions using scoria: kinetics and equilibria of sorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 174, 307–313 (2010).

Kadirvelu, K., Faur-Brasquet, C. & Cloirec, P. L. Removal of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Ni(II) by Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Cloths. Langmuir 16, 8404–8409 (2000).

Boparai, H. K., Joseph, M. & O’Carroll, D. M. Cadmium (Cd2+) removal by nano zerovalent iron: surface analysis, effects of solution chemistry and surface complexation modeling. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 20, 6210–6221 (2013).

Yang, S. et al. Impact of environmental conditions on the sorption behavior of Pb(II) in Na-bentonite suspensions. J. Hazard. Mater. 183, 632–640 (2010).

Awual, M. R. Innovative composite material for efficient and highly selective Pb(II) ion capturing from wastewater. J Mol Liq 284, 502–510 (2019).

Awual, M. R., Hasan, M. M., Rahman, M. M. & Asiri, A. M. Novel composite material for selective copper(II) detection and removal from aqueous media. J Mol Liq 283, 772–780 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF- 2017R1A2B2009033) as well as by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, South Korea as a part of the project titled ‘Development on technology for offshore waste final disposal’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.H., W.R.L. and C.H.L. wrote the manuscript; W.R.L., C.H.L. and H.J.P. conducted the experiment using the composite mineral adsorbents; S.W.K., E.K.C., M.H.O. and S.N.S. developed the composite mineral adsorbents.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, WR., Kim, S.W., Lee, CH. et al. Performance of composite mineral adsorbents for removing Cu, Cd, and Pb ions from polluted water. Sci Rep 9, 13598 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49857-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49857-9

This article is cited by

-

Fabrication of polyamide-12/cement nanocomposite and its testing for different dyes removal from aqueous solution: characterization, adsorption, and regeneration studies

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

A review on zeolites as cost-effective adsorbents for removal of heavy metals from aqueous environment

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2022)

-

A promising chitosan/fluorapatite composite for efficient removal of lead (II) from an aqueous solution

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2021)

-

The influence of application of biochar and metal-tolerant bacteria in polluted soil on morpho-physiological and anatomical parameters of spring barley

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.