Abstract

The presently increasing demand for rare earth elements (REE), particularly in high-tech and “green energy” applications, has led to global interest in the distribution, origins and formation conditions of REE deposits. The World’s first hard-rock REE sources, the polymetallic deposits of Bastnäsfältet in Bergslagen, central Sweden, were also the place of the original discovery of several REE and many of their host minerals. Similar deposits with high concentrations of REE occur along a > 100 km corridor in the region and they share a number of geological and mineralogical features; all comprising Palaeoproterozoic, skarn-hosted magnetite-REE mineralisation of ambiguous origin. Here we report oxygen isotope data for magnetite and quartz, and oxygen and carbon isotope data for carbonates from ten of these classic deposits, to model and assess their mode of origin. Combined with existing geological observations, the isotope results support an origin in a c. 1.9 Ga shallow-marine back-arc, sub-seafloor setting, where felsic magmatic-sourced, high-temperature fluids reacted with pre-existing limestone interlayers, leading to localised skarn formation and magnetite-REE-mineral precipitation. These findings help us to better understand the geological processes that have produced economic REE mineralisation and may assist future exploration for these critical commodities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

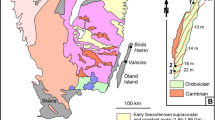

The rare earth elements (REE) are critical components in a vast range of modern high-tech products and technologies. These include many types of industrial, research and consumer electronics, as well as increasingly abundant “green energy” applications such as wind power and electric vehicles1,2,3,4,5. Economic projections suggest an even greater demand for REE in the immediate future, especially since numerous countries aim at phasing out fossil fuel-based transportation and energy production6,7. This demand, combined with the present lead of China as the main supplier of REE, has led to a renewed global interest in REE deposits of various types and geological origins. In Europe, one of the regions with the largest exploration potential for critical metals such as the REE is the Fennoscandian Shield (Fig. 1), where a multitude of REE-bearing mineralisations occur8. Of these, one of the most iconic, yet puzzling ore types is the REE-enriched magnetite skarns in the Palaeoproterozoic Bergslagen ore province in south central Sweden (Fig. 1). While not being mined at present, their presence and high grades have warranted recent and on-going exploration for REE in the area.

Maps and sampling locations. (a) Overview map of the Fennoscandian Shield and part of the Caledonian orogen (yellow), with the Bergslagen ore province (stippled line) and the REE-line (black) indicated. (b) Geological map of the REE-line, Bergslagen, central Sweden. The ten Bastnäs-type deposits sampled in this study are marked. The towns of Nora, Riddarhyttan and Norberg are included as landmarks. Grid is Swedish national grid RT90.

The mines of Bastnäsfältet (the Bastnäs field) in Bergslagen (Fig. 1), and in particular Ceritgruvan (the cerite mine), was from the mid-19th century where the first hard-rock underground mining was performed to extract REE9. The main REE minerals in the ore are cerite-(Ce) [(Ce,LREE,Ca)9(Mg,Fe)[SiO4]6[SiO3OH](OH)3] and ferriallanite-(Ce) [Ca(Ce,LREE)Fe3+AlFe2+[SiO4][Si2O7]O(OH)]. Moreover, Bastnäsfältet was also the location of the original discovery of cerium, lanthanum, and “didymium” (a mixture from which praseodymium and neodymium were later isolated)10,11,12, as well as numerous minerals, including the already mentioned cerite and the eponymous bastnäsite-(Ce) [(Ce,LREE)(CO3)F]11,13. After the initial discovery at Bastnäsfältet by Hisinger14, bastnäsite was to become one of the World’s major sources of REE4. As additional mineralisations were recognised to have a similar character as those at Bastnäsfältet, the term “Bastnäs-type deposit” was coined15,16. The Bastnäs-type deposits are characterised by skarn-hosted magnetite-REE mineralisation, with or without additional polymetallic assemblages11,15,17. These deposits occur as clusters along the so-called “REE-line”18; a more than 100 km long, narrow belt in the western Bergslagen region of variably Na, K and/or Mg altered, c. 1.90–1.88 G.y. old felsic metavolcanic rocks with intercalated marble layers (Fig. 1). This volcano-sedimentary sequence formed during magmatic activity in what has been interpreted as a shallow-marine, but principally continental back-arc setting19. Both the magnetite-REE ore bodies and the host rocks have been affected by later, polyphase deformation and greenschist to amphibolite facies metamorphism at c. 1.85–1.80 Ga during the Svecokarelian orogeny20,21,22,23. In the Bergslagen ore province, where base metal mineralisations and iron oxide ores predominate23,24,25,26,27, the REE-line represents both a geological anomaly and a zone of significant concentration of in general light REE, but also yttrium, and the heavy REE16. The REE minerals in these deposits are dominantly silicates [allanite- and dollaseite-group minerals, cerite-(Ce), fluorbritholite-(Ce), törnebohmite-(Ce)], and the carbonate bastnäsite-(Ce), besides numerous low-volume accessory phases16,17. The skarns hosting the magnetite-REE mineralisations are calc-silicate aggregates, typically amphibole-dominated, featuring actinolitic to tremolitic, as well as anthophyllitic compositions28,29,30. Magnetite was always the main ore mineral mined in these deposits, besides the REE mineralisations, but copper as well as cobalt ores have also been locally exploited29,30.

The genesis of the Bastnäs-type REE deposits has been critically debated with respect to their formation process, and their temporal relationships to host rocks and to other mineralisation types11,15,16,17,18,28,30,31. Their genesis, and that of the associated skarn iron ores and extensive host rock alteration, was originally interpreted to be related to large-scale, so-called “magnesia metasomatic” processes, generated by abundant granitoid intrusions during the waning stage of regional (Svecokarelian) metamorphism15,27. Later studies have rendered this theory obsolete17,18,31,32, and they mostly revolve around an essentially syn-volcanic hydrothermal formation scenario at c. 1.90–1.88 Ga, or somewhat later. Here we employ mineral oxygen and carbon isotopes to unravel the fundamental process involved in the formation of the Bastnäs-type REE deposits, and to provide robust constraints on the temperature and source(s) of ore-forming fluids.

Results and Interpretation

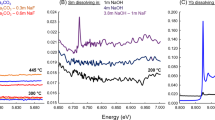

Representative, variably mineralised rock samples were both collected in the field and sourced from the collections of the Geological Survey of Sweden in Uppsala and the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. The sample suite encompasses ten different Bastnäs-type deposits from within the REE-line, Bergslagen (Fig. 1), and comprises massive magnetite ore (from Bastnäsfältet, Myrbacksfältet, Östra Gyttorpsgruvan and Rödbergsgruvan), skarn and skarn ore with disseminated-type magnetite (from Knutsbogruvorna, Östanmossagruvan, Södra Hackspikgruvan, Johannagruvan, Malmkärragruvan and Bastnäsfältet) and magnetite-skarn-bearing banded iron formation (BIF) ore (from Högforsfältet; Table 1). Magnetite concentrates (n = 25) were separated from all the ore types and have δ18O values ranging from −2.3 to +2.6‰, whereas co-existing quartz (n = 3) separated from the BIF-hosted magnetite-skarn assemblages have δ18O values between +7.2 and +8.3‰ (Table 1). Carbonate minerals (n = 12) were separated from a suite of the variably magnetite- and REE-bearing skarn assemblages. The carbonate separates comprise both calcite [CaCO3] and dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2], as well as mixtures between the two, and have δ18O values from +5.8 to +10.0‰ and δ13C values from −5.4 to −2.8‰ (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Distribution of δ18O and δ13C values and numerical models for carbonates from Bergslagen. The analysed carbonates associated with magnetite-REE mineralisation in Bastnäs-type deposits (blue diamonds; this study) and complementary data (blue triangles) from Holtstam et al.31 are shown. Also shown are literature data for carbonates from the Bergslagen province (red dots)34, encompassing non-mineralised, Palaeoproterozoic marine carbonate rocks (blue field), carbonates from stratiform iron oxide deposits (purple field), carbonates from iron oxide skarn deposits (grey field), and carbonates from granite-related tungsten-molybdenum (W-Mo) skarn deposits (red field). Reference fields for Proterozoic marine calcite and dolomite (brown field)56 and primary magmatic waters (yellow field)35,37,38,39,40,41 are also included. Trajectories A-C represent Rayleigh-type de-volatilisation of local, non-mineralised marine carbonate rocks of average composition, using the indicated fractionation factors35. Lines 1–3 are binary mixing trajectories at 5% intervals between local marine carbonate rocks and a typical magmatic aqueous fluid composition. The calculated magmatic fluid-carbonate mixing trajectories envelop essentially all of the analysed carbonates from the Bastnäs-type deposits. See text for detailed explanation.

Thermometry

Thermometric calculations for magnetite-quartz oxygen isotope pairs (n = 3), using the fractionation factor of Zheng & Simon33, yielded a temperature range of 425 to 545 ± 25 °C (Table 1). Although only a small dataset, these temperatures are in agreement with published fluid inclusion data for bastnäsite-(Ce) from the REE-line. The fluid inclusions are moderately to highly saline (6–29 wt.% CaCl2) and show (uncorrected) homogenisation temperatures of 370 to 460 °C31. Considering that significant lithostatic pressures are likely to have prevailed at the depths of skarn formation (c.f.19), and that, in general, bastnäsite-(Ce) is paragenetically late relative to magnetite, the fluid inclusion homogenisation temperatures should represent lower-end estimates of the range of mineralisation temperatures. Thus, the combined oxygen isotope and fluid inclusion evidence suggest that primary magnetite-REE mineralisation in Bastnäs-type deposits formed, at least initially, from fluids with temperatures of ≥450 °C.

Oxygen and carbon isotope modelling for carbonates

The carbonates from Bastnäs-type deposits have δ18O and δ13C values that are significantly lower than those of non-mineralised, Palaeoproterozoic marine carbonate rocks in the Bergslagen province (δ18O = +12.5 to +19.6‰, δ13C = −1.8 to +1.7‰34; Fig. 2). However, they plot partly within the fields for previously analysed carbonates from iron oxide skarns and carbonates from granite-related (metasomatic) tungsten-molybdenum skarns34 (Fig. 2). To test for possible process scenarios behind the observed shifts in carbonate isotopic compositions for the Bastnäs-type deposits, we calculated two different numerical models. Trajectories A–C in Fig. 2 represent Rayleigh-type de-volatilisation of non-mineralised, Palaeoproterozoic marine carbonate rocks of average composition. Rayleigh de-volatilisation is defined as (shown for δ18O below):

where F is the molar fraction of oxygen that remains in the rock after de-volatilisation; α is the fractionation factor; and δ18Oi and δ18Of are the initial and final oxygen isotope compositions of the rock, respectively35. This model is based on the so-called “calc-silicate limit“, which assumes that all carbon is released as CO2 while c. 60% of the oxygen remains in the rock if the reaction goes to completion35. Unlike what has locally been observed in other marble-skarn environments in Bergslagen (e.g.36), the analysed carbonates from the Bastnäs-type deposits do not plot on the steep or near-vertical trends of pure thermal decarbonation (A-C in Fig. 2). These results suggest that such reactions alone cannot realistically have produced the observed isotopic distribution. Lines 1–3 in Fig. 2, in turn, represent binary mixing trajectories between the same non-mineralised, Palaeoproterozoic marine carbonates and a typical magmatic aqueous fluid composition (δ18O = +5.3 to +10.0‰, δ13C = −8.0 to −4.0‰)35,37,38,39,40,41, using different end-member compositions. Mixing is defined as:

where RM is the isotope ratio of element X in a mixture of compositions A and B; XA and XB are the concentration of X in A and B, respectively; and f is the weight fraction of A defined as f = A/(A + B)41. The calculated magmatic fluid-carbonate mixing trajectories envelop essentially all of the analysed carbonates from the Bastnäs-type deposits (Fig. 2). Based on these results, we interpret that progressive CO2 release during interaction between a magmatic-derived, aqueous hydrothermal fluid and local, marine carbonate horizons caused the observed shifts to lower δ18O and δ13C values in the primary (protolith) carbonates, as well as re-precipitation of secondary (hydrothermal) carbonates of similar compositions (cf.35,42,43,44). Such processes have, notably, been recognised at magnetite skarn deposits elsewhere (e.g. Turgai belt, Kazakhstan45) and at several magma-carbonate contacts (e.g. Vesuvius volcanic system, Italy46 and Merapi volcano, Indonesia47).

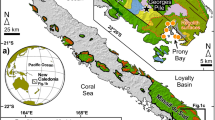

Oxygen isotope fluid modeling

Oxygen isotope compositions of hydrothermal aqueous fluids in equilibrium with magnetite from Bastnäs-type deposits were modelled for a temperature range of 200 to 600 °C (Fig. 3A), using the average (−0.4‰), minimum (−2.3‰) and maximum (+2.6‰) δ18O values measured in magnetite, respectively, and established fractionation factors33. For the proposed temperatures of mineralisation (c. 370 to 545 °C), fluids in equilibrium with magnetite of average composition have δ18O values ranging from +6.4 to +7.6‰ (Fig. 3A). These results are consistent with equilibration between magnetite and a magmatic-derived fluid (δ18O = +5.3 to +10.0‰)35,37,38,39,40,41. If the upper end of the temperature range is used, fluids in equilibrium with magnetite with the lowest δ18O value are slightly lower than primary magmatic waters (δ18O = +4.5‰; Fig. 3A). This trend may reflect mixing between original magmatic fluids and surface water with lower δ18O value. For the lower end of the temperature range, fluids in equilibrium with magnetite with the highest δ18O value are, in turn, higher than typical magmatic waters (δ18O = +10.7‰; Fig. 3A). Higher-than-magmatic fluid δ18O values are explained by interaction with pre-existing carbonate rocks (Fig. 3A).

Oxygen isotope compositions of aqueous fluids in equilibrium with magnetite and carbonates from Bastnäs-type deposits at temperatures of 200 to 600 °C. (a) Equilibrium fluid compositions calculated based on the average, minimum and maximum δ18O values measured in magnetite, respectively. The red stippled lines indicate fluid compositions for specific temperatures, within the range given by magnetite-quartz oxygen isotope pairs and published fluid inclusion data for bastnäsite-(Ce)31. Reference fields include primary magmatic waters35,37,38,39,40,41, local carbonate rocks34 and the SMOW line. (b) Similarly modelled oxygen isotope compositions of equilibrium fluids for carbonates. The combined magnetite-carbonate data imply an initially high-temperature, magmatic-dominated hydrothermal system that evolved through decreasing temperature and an increasing input from non-magmatic, low-δ18O fluid sources. See text for detailed explanation. Abbreviations: Bas – bastnäsite; Cb – carbonate; FI – fluid inclusions; Mgt – magnetite; Qtz – Quartz; SMOW – Standard Mean Ocean Water.

The oxygen isotope compositions of hydrothermal fluids in equilibrium with carbonates from these deposits were also calculated for temperatures of 200 to 600 °C (Fig. 3B), based on the fractionation factors of Zheng48 and Sheppard & Schwarz49. Equilibrium fluid δ18O values in the range of primary magmatic waters, from +5.8 to +8.0‰, are only produced for the highest δ18O value (+10.0‰) of the analysed carbonates (Fig. 3B). The average (+7.4‰) and lowest (+5.8‰) carbonate δ18O values give significantly lower equilibrium fluid δ18O values. With decreasing temperature, they range from the lowermost limit of magmatic fluids down to +2.0‰ (Fig. 3B). Unlike the physically and chemically refractory magnetite, which is much more likely to retain its original chemical and isotopic composition (e.g.50,51), the reactive carbonates are more easily affected by both high-temperature processes that could lead to, e.g., de-volatilisation, and low-temperature fluid overprinting, either during primary skarn and ore formation or during subsequent phases of regional metamorphism and granitoid intrusion. Such retrograde isotopic modification may be more marked in some carbonates than in others, explaining the variation in carbonate equilibrium fluid δ18O values (Fig. 3B) relative to the more limited, essentially magmatic range for magnetite fluids (Fig. 3A).

Overall, the gradual transition from higher to lower equilibrium fluid δ18O values observed in the combined magnetite-carbonate datasets suggests that they record the progressive evolution of a hydrothermal system that commenced with high-temperature, magmatic-dominated fluids, via decreasing temperatures and gradual input (dilution) from external, non-magmatic water sources.

Conclusions

The new oxygen and carbon isotope data together with the generated numerical models demonstrate that the magnetite-REE-mineralised skarn assemblages from Bergslagen formed from high-temperature hydrothermal fluids of a predominantly magmatic origin. These fluids reacted with local, Palaeoproterozoic marine carbonate rocks and, over time, the hydrothermal system cooled and experienced influx of isotopically distinct (low-δ18O) water sources, such as seawater. Combined with available geological, geochronological and textural observations15,16,17,18,19,23,28,29,30,31,32, the new results are most easily reconciled with a scenario involving sub-seafloor, felsic magmatic activity at c. 1.90–1.88 Ga, within a shallow-marine back-arc setting (Fig. 4). In this setting, magmatic-sourced, metal- and silica-rich hydrothermal fluids were introduced to, and reacted with limestone interlayers in an otherwise pyroclastic-dominated volcano-sedimentary succession, leading to skarn formation and magnetite-REE-mineralisation.

Cartoon model illustrating a likely scenario during the formation of the Bastnäs-type REE deposits in Bergslagen. These deposits are interpreted to have formed in a c. 1.9 Ga shallow-marine back-arc, sub-seafloor setting associated with extensive felsic volcanism and plutonism. High-temperature hydrothermal fluids, enriched in silica, iron and REE among other components, exsolved from a sub-volcanic magma and reacted with nearby interlayers of limestone and carbonate-bearing BIF. This led to skarn formation and magnetite-REE-precipitation within the carbonate units, while extensive hydrothermal alteration affected the surrounding volcanic host rocks. Over the life of the hydrothermal system there was progressive involvement of surface waters. See text for detailed explanation.

Our study provides new evidence for a magmatic origin of the World’s original hard-rock source of REE, the Bastnäs-type REE deposits of central Sweden. These findings help us to better constrain the geological processes associated with formation of economic REE mineralisation, and will thus assist exploration for these critical commodities in the future. Specifically, the Bastnäs-type deposits represent a large-scale (>100 km) feature of high-grade REE concentration in the Bergslagen province (Fig. 1), but are currently unknown in the form of direct analogues from other locations globally. We propose that geological terranes elsewhere that constitute shallow-marine, sub-seafloor settings within continental back-arcs may be prospective for Bastnäs-type REE mineralisation. In such settings, evidence of extensive felsic magmatism combined with the presence of nearby carbonate horizons constitute key first-order exploration criteria (Fig. 4). Determining the cause of original REE enrichment in the magmatic systems that produced Bastnäs-type deposits, and whether or not it is unique to this tectonic setting, remains an important avenue for future research.

Methods

Mineralogical characterisation

Representative rock samples were cut and prepared as polished thin and thick sections, and subjected to transmitted and reflected polarised light microscopy and reconnaissance scanning electron microscopy with an energy dispersive scanning system (SEM-EDS). In selected cases, subsequent field emission electron microprobe analyses (FE-EPMA) were performed on a JEOL JXA-8530F Hyperprobe at the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University.

To determine the composition of carbonate separates prior to stable isotope measurements, samples were subjected to powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm. The samples were first crushed to a fine powder and placed in a silicon holder. They were then analysed using a PANalytical X’pert PRO automated diffractometer, utilising an acceleration voltage of 45 kV and a beam current of 40 mA. The 2θ angles were measured in the interval 5–70° for 11 minutes, and mineral identification was done off-line using the Highscore Plus software.

Stable isotopes

Stable isotope data were produced at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Magnetite and quartz separates were analysed following the laser fluorination technique described in Harris & Vogeli52. Each sample was reacted in the presence of 10 kPa BrF5, after which purified O2 gas was collected onto a 5 Å molecular sieve within a glass storage bottle. Carbonate separates were analysed using a conventional carbonate line, where purified CO2 gas was extracted after reacting the samples with 100% phosphoric acid53. Oxygen isotope ratios of magnetite, quartz and carbonates, and carbon isotope ratios of carbonates, were measured off-line using a Finnigan Delta XP mass spectrometer in dual-inlet mode. For magnetite and quartz analysed using laser fluorination, the Monastery Garnet standard54 was used to normalise the raw data and to correct for drift. Carbonates were analysed alongside the Namaqualand Marble standard55, and the raw data was corrected based on the calcite:dolomite ratio determined previously for each sample by XRD. The δ18O data are reported in per mil (‰) relative to the Standard Mean Ocean Water (SMOW) standard, and the δ13C data in per mil relative to the Pee Dee Belemnite (PDB) standard. Both types of analyses gave 2σ errors of 0.2‰.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data are available within the article.

References

Haxel, G., Hedrick, J. & Orris, G. Rare earth elements — critical resources for high technology. USGS Fact Sheet 087–02 (2002).

Hatch, G. Dynamics in the global market for rare earths. Elements 8, 341–346 (2012).

Chakhmouradian, A. R. & Wall, F. Rare earth elements: minerals, mines, magnets (and more). Elements 8, 333–340 (2012).

Wall, F. Rare earth elements. In Critical Metals Handbook (ed. Gunn, A. G.) 312–339 (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Guyonnet, D. et al. Material flow analysis applied to rare earth elements in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 107, 1–26 (2015).

Alonso, E. et al. Evaluating rare earth element availability: a case with revolutionary demand from clean technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3406–3414 (2012).

Binnemans, K. et al. Recycling of rare earths: a critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 51, 1–22 (2013).

Goodenough, K. M. et al. Europe’s rare earth element resource potential: an overview of metallogenetic provinces and their geodynamic setting. Ore Geol. Rev. 72, 838–856 (2016).

Carlborg, H. Ekonomisk-teknisk beskrivning. In Riddarhytte Malmfält i Skinnskattebergs Socken, Västmanlands Län. 139–343 (Victor Pettersson, 1923).

Hisinger, W. & Berzelius, J. Cerium, en ny Metall, Funnen i Bastnäs Tungsten från Riddarhyttan i Westmanland. 24 p. (Henrik A. Nordström, 1804).

Andersson, U. B. et al. The Bastnäs-type REE mineralisations in north-western Bergslagen, Sweden. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Rapp. Medd. 119, 34 (2004).

Williams-Jones, A. E., Migdisov, A. A. & Samson, I. M. Hydrothermal mobilisation of the rare earth elements – a tale of “ceria” and “yttria”. Elements 8, 355–360 (2012).

Jonsson, E. et al. The Norra Kärr REE-Zr Project and the Birthplace of Light REEs: Excursion Guidebook SWE3, SWE6 & SWE7. 82 p. (Society for Geology Applied to Mineral Deposits, 2013).

Hisinger, W. Analyser af några svenska mineralier 2: basiskt fluor-cerium från Bastnäs. K. Vet. Akad. Handl. 187, 1–9 (1838).

Geijer, P. The geological significance of the cerium mineral occurrences of the Bastnäs type in central Sweden. Arkiv Mineral. Geol. 3, 99–105 (1961).

Holtstam, D. & Andersson, U. B. The REE minerals of the Bastnäs-type deposits, south-central Sweden. Can. Mineral. 45, 1073–1114 (2007).

Jonsson, E., Högdahl, K., Sahlström, F., Nysten, P. & Sadeghi, M. The Palaeoproterozoic skarn-hosted REE mineralisations of Bastnäs-type: overview and mineralogical-geological character. In ERES Abstracts and Proceedings 1, 382–389 (2014).

Jonsson, E. & Högdahl, K. New evidence for the timing of formation of Bastnäs-type REE mineralisation in Bergslagen. In Proceedings of the Biennial SGA Meeting (eds Jonsson, E. et al.) 12, 1724–1727 (2013).

Allen, R. L., Lundström, I., Ripa, M., Simeonov, A. & Christofferson, H. Facies analysis of a 1.9 Ga, continental margin, back-arc, felsic caldera province with diverse Zn-Pb-Ag-(Cu-Au) sulfide and Fe oxide deposits, Bergslagen region, Sweden. Econ. Geol. 91, 979–1008 (1996).

Welin, E. Isotopic results of the Proterozoic crustal evolution of south-central Sweden; review and conclusions. GFF 114, 299–312 (1992).

Andersson, U. B., Högdahl, K., Sjöström, H. & Bergman, S. Multistage growth and reworking of the Palaeoproterozoic crust in the Bergslagen area, southern Sweden: evidence from U–Pb geochronology. Geol. Mag. 143, 679–697 (2006).

Hermansson, T., Stephens, M. B., Corfu, F., Andersson, J. & Page, L. Penetrative ductile deformation and amphibolite-facies metamorphism prior to 1851 Ma in the western part of the Svecofennian orogen, Fennoscandian Shield. Precambr. Res. 153, 29–45 (2007).

Stephens, M. B. et al. Synthesis of the bedrock geology in the Bergslagen region, Fennoscandian Shield, south-central Sweden. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. Ba 58, 259 (2009).

Tegengren, F. Sveriges ädlare malmer och bergverk. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. Ca 17, 406 (1924).

Magnusson, N. H. Persbergs Malmtrakt och Berggrunden i de Centrala Delarna av Filipstads Bergslag. 231 p. (Victor Petterson, 1925).

Geijer, P. & Magnusson, N. H. De mellansvenska järnmalmernas geologi. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. Ca 35, 654 (1944).

Magnusson, N. H. The origin of the iron ores in central Sweden and the history of their alterations. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. C 643, 127 (1970).

Geijer, P. The cerium minerals of Bastnäs at Riddarhyttan. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. C 304, 24 (1921).

Geijer, P. Geologisk beskrivning. In Riddarhytte Malmfält i Skinnskattebergs Socken, Västmanlands Län. 1–138 (Victor Pettersson, 1923).

Geijer, P. Norbergs berggrund och malmfyndigheter. Sver. Geol. Undersök. Ser. Ca 24, 162 (1936).

Holtstam, D., Andersson, U. B., Broman, C. & Mansfeld, J. Origin of REE mineralisation in the Bastnäs-type Fe-REE-(Cu-Mo-Bi-Au) deposits, Bergslagen, Sweden. Miner. Deposita 49, 933–966 (2014).

Andersson, U. B., Holtstam, D. & Broman, C. Additional data on the age and origin of the Bastnäs-type REE deposits, Sweden. In Proceedings of the Biennial SGA Meeting (eds. Jonsson, E. et al.) 12, 1639–1642 (2013).

Zheng, Y.-F. & Simon, K. Oxygen isotope fractionation in hematite and magnetite: a theoretical calculation and application to geothermometry of metamorphic iron-formations. Eur. J. Mineral. 3, 877–886 (1991).

De Groot, P. A. & Sheppard, S. M. Carbonate rocks from W. Bergslagen, central Sweden: isotopic (C, O, H) evidence for marine deposition and alteration by hydrothermal processes. Geol. Mijnbouw 67, 177–188 (1988).

Valley, J. W. Stable isotope geochemistry of metamorphic rocks. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 16, 445–489 (1986).

Jonsson, E. Fissure-Hosted Mineral Formation and Metallogenesis in the Långban Fe-Mn-(Ba-As-Pb-Sb…) Deposit, Bergslagen, Sweden. 110 p. (PhD thesis, Stockholm University, 2004).

Taylor, H. P. The application of oxygen and hydrogen isotope studies to problems of hydrothermal alteration and ore deposition. Econ. Geol. 69, 843–883 (1974).

Sheppard, S. M. Characterization and isotopic variations in natural waters. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 16, 165–183 (1986).

Taylor, B. E. Magmatic volatiles; isotopic variation of C, H, and S. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 16, 185–225 (1986).

Taylor, B. E. Degassing of H2O from rhyolite magma during eruption and shallow intrusion, and the isotopic composition of magmatic water in hydrothermal systems. Geol. Surv. Japan Report 279, 190–194 (1992).

Bowman, J. R. Stable-isotope systematics in skarns. Mineral. Assoc. Can. Short Course 26, 1–49 (1998).

Taylor, B. E. & O’Neil, J. R. Stable isotope studies of metasomatic Ca-Fe-Al-Si skarns and associated metamorphic and igneous rocks, Osgood Mountains, Nevada. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 63, 1–49 (1977).

Bowman, J. R., O’Neil, J. R. & Essene, E. J. Contact skarn formation at Elkhorn, Montana, II: origin and evolution of C-O-H skarn fluids. Am. J. Sci. 285, 621–660 (1985).

Orhan, A., Mutlu, H. & Fallick, A. E. Fluid infiltration effects on stable isotope systematics of the Susurluk skarn deposit, NW Turkey. J. Asian Earth Sci. 40, 550–568 (2011).

Hawkins, T. et al. The geology and genesis of the iron skarns of the Turgai belt, northwestern Kazakhstan. Ore Geol. Rev. 85, 216–246 (2017).

Jolis, E. et al. Skarn xenolith record crustal CO2 liberation during Pompeii and Pollena eruptions, Vesuvius volcanic system, central Italy. Chem. Geol. 415, 17–36 (2015).

Whitley, S. et al. Crustal CO2 contribution to subduction zone degassing recorded through calc-silicate xenoliths in arc lavas. Sci. Rep. 9, 8803, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44929-2 (2019).

Zheng, Y.-F. Oxygen isotope fractionation in carbonate and sulfate minerals. Geochem. J. 33, 109–126 (1999).

Sheppard, S. M. & Schwarz, H. P. Fractionation of carbon and oxygen isotopes and magnesium between coexisting metamorphic calcite and dolomite. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 26, 161–198 (1970).

Johnson, C. A. Partitioning of zinc among common ferromagnesian minerals and implications for hydrothermal mobilization. Can. Mineral. 32, 121–132 (1994).

Jonsson, E. et al. Magmatic origin of giant ‘Kiruna-type’ apatite-iron-oxide ores in Central Sweden. Sci. Rep. 3, 1644, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01644 (2013).

Harris, C. & Vogeli, J. Oxygen isotope composition of garnet in the Peninsula Granite, Cape Granite Suite, South Africa: constraints on melting and emplacement mechanisms. S. Afr. J. Geol. 113, 401–412 (2010).

McCrea, J. M. On the isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale. J. Chem. Phys. 18, 849–857 (1950).

Harris, C., Smith, H. S. & le Roex, A. P. Oxygen isotope composition of phenocrysts from Tristan da Cunha and Gough Island lavas: variation with fractional crystallization and evidence for assimilation. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 138, 164–175 (2000).

Faure, K., Harris, C. & Willis, J. P. A profound meteoric water influence on genesis in the Permian Waterberg coalfield, South Africa: evidence from stable isotopes. J. Sediment. Res. 65, 605–613 (1995).

Veizer, J. & Hoefs, J. The nature of O18/O16 and C13/C12 secular trends in sedimentary carbonate rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 40, 1387–1395 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This study was performed within the framework of a project on rare and critical metals in central Swedish mine dumps and associated mineralisations, funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet). Additional support from the Geological Survey of Sweden is acknowledged. We thank Sherissa Roopnarain, Jaroslaw Majka and Gary Wife for technical assistance during the stable isotope, FE-EPMA and SEM-EDS analyses, respectively. We also thank Jörgen Langhof for helpful assistance during sampling at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.J. and K.H. conceived the study. Field work and sampling were carried out by E.J. and K.H. Sample preparation was done by F.S. Mineralogical analyses were performed by F.S., E.J. and F.W. Isotope analyses and data interpretation were carried out by C.H., F.S., E.J., V.R.T., E.M.J. and K.H., while illustrations were prepared by F.S. and K.H. The manuscript was written by F.S. and E.J. with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahlström, F., Jonsson, E., Högdahl, K. et al. Interaction between high-temperature magmatic fluids and limestone explains ‘Bastnäs-type’ REE deposits in central Sweden. Sci Rep 9, 15203 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49321-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49321-8

This article is cited by

-

Crystal chemistry of ferriallanite-(Ce) from Nya Bastnäs, Sweden: Chemical and spectroscopic study

Mineralogy and Petrology (2023)

-

Iron isotopes constrain sub-seafloor hydrothermal processes at the Trans-Atlantic Geotraverse (TAG) active sulfide mound

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.