Abstract

Heteroresistance - the simultaneous presence of drug-susceptible and -resistant organisms - is common in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In this study, we aimed to determine the limit of detection (LOD) of genotypic assays to detect gatifloxacin-resistant mutants in experimentally mixed populations. A fluoroquinolone-susceptible M. tuberculosis mother strain (S) and its in vitro selected resistant daughter strain harbouring the D94G mutation in gyrA (R) were mixed at different ratio’s. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against gatifloxacin were determined, while PCR-based techniques included: line probe assays (Genotype MTBDRsl and GenoScholar-FQ + KM TB II), Sanger sequencing and targeted deep sequencing. Droplet digital PCR was used as molecular reference method. A breakpoint concentration of 0.25 mg/L allows the phenotypic detection of ≥1% resistant bacilli, whereas at 0.5 mg/L ≥ 5% resistant bacilli are detected. Line probe assays detected ≥5% mutants. Sanger sequencing required the presence of around 15% mutant bacilli to be detected as (hetero) resistant, while targeted deep sequencing detected ≤1% mutants. Deep sequencing and phenotypic testing are the most sensitive methods for detection of fluoroquinolone-resistant minority populations, followed by line probe assays (provided that the mutation is confirmed by a mutation band), while Sanger sequencing proved to be the least sensitive method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heteroresistance, a phenomenon defined as co-existence of drug-susceptible (usually wildtype; WT) and drug-resistant (usually mutant) organisms in the same sample or clinical isolate, can result from the concurrent presence of two different strains (mixed infection) or from a changing bacterial subpopulation within the same strain (clonal evolution)1. It is common in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has been reported for several antibiotics, and is suggested to cause worse treatment outcome in tuberculosis2. Rapid detection of heteroresistance can be important to prevent selection of DR during antibiotics treatment3.

The capacity of phenotypic and genotypic assays to detect heteroresistance largely depends on the technique applied. Phenotypic drug-susceptibility testing (pDST), based on the proportion method as originally described by Canetti4, aims to determine whether 1% or more of the bacterial population is drug resistant. Accordingly, genotypic assays should be able to detect the simultaneous presence of WT and mutant populations of the relevant genes at different ratios.

Although most studies describing resistance to fluoroquinolones (FQs) among clinical isolates do not provide specific data on heteroresistance, the few studies that do, report frequencies ranging from 14% to 38% of all FQ resistance in some high burden countries, suggesting that FQ specific heteroresistance may be more common than heteroresistance to other anti-TB drugs and relevant for predicting the response to treatment with FQs2,5,6,7,8,9,10. In this study, we aimed to determine the limit of detection (LOD) of genotypic assays to detect gatifloxacin resistant mutants in experimentally mixed populations relative to the LOD of 1% for phenotypic assays. Gatifloxacin is a powerful fourth generation FQ11. We compared culture-based determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and PCR-based techniques: line probe assays (LPAs), Sanger sequencing and targeted next generation sequencing (targeted NGS). Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) served as reference method for absolute quantification and detection of mutant DNA, as its technological principles enable the accurate detection of rare mutations in a background of wildtype sequences, including drug-resistant subpopulations12,13,14,15.

Results

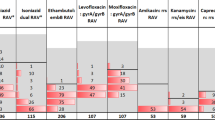

The average fractional abundance of the D94G allele by ddPCR was ≥99.9% for R100S0 triplicates, while none was detected in R0S100 or H37Rv. In the mixtures, fractional abundance of the D94G mutant was detected with overall increasing frequencies from R1S99 to R50S50, albeit with intra- and inter-experiment variability (Table 1; Fig. 1; See web-only Supplementary Table). In the third experiment, an internal inconsistency was observed with an abundance of 21.6% for R10S90 compared to only 16.9% for R20S80 and 20.1% for R40S60.

Phenotypic analysis showed an MIC < 0.25 mg/L in all triplicates for the fully susceptible control suspension (R0S100) and the H37Rv control strain (Table 1). The R1S99 suspensions had an MIC of 0.5 mg/L in all triplicates (i.e. growth on 0.25 mg/L that exceeded growth on the 1/100 diluted control), whereas the R5S95 suspension showed an MIC of 0.5 mg/L in replicate 2 and 1.0 mg/L in the other two replicates. The higher MIC observed for R5S95 replicates 1 and 3 is in line with the higher than expected ddPCR value of 9.2% mutants for these replicates. The remaining heteroresistant bacterial suspensions and the fully resistant suspension showed an MIC of 1.0 mg/L. Longer incubation of the tubes (three versus six weeks) did not alter MIC values. Applying a breakpoint concentration of 0.25 mg/L would allow detection of ≥1% (R1S99) resistant bacilli, whereas a breakpoint of 0.5 mg/L would allow detecting on average 7.9% (6.5–9.2) (R5S95) resistant bacilli.

On LPA testing, the WT band was absent and the mutant band present for all R100S0 suspensions in both assays, while for the R0S100 and R1S99 suspensions and the H37Rv control strain only the WT band was present. The MTBDRsl allowed detection of heteroresistance when on average 7.4% (5.9–8.8)(R5S95) of the mutant bacteria were present, whereas below 3.7% mutants (R1S99) remained undetected (Table 1; See web-only Supplementary Fig. 2). Testing of a single sample set on MTBDRsl version 2 did not alter the outcome (See web-only Supplementary Fig. 2). The FQ + KM TB II showed higher variability of the results, with the LOD varying from R5S95 to R30S70 across replicates. The assay was less sensitive, requiring on average ≥17.3% (15.5–19.2) mutants for a clear 2c band to be observed (Table 1; See web-only Supplementary Fig. 3). Testing of the additional sample set with the D94G mutation alone allowed the detection of 5% mutants visualized by probe 2a (See web-only Supplementary Fig. 3).

The automated analysis of Sanger sequences unequivocally revealed the ambiguous ‘R’ call, within the range of 21% to 55% resistant bacilli (Table 1; See web-only Supplementary Fig. 4). Around 15%, sequences showed slightly varying peak heights resulting in different software interpretation: in replicate 1 heteroresistance was detected at 14.4% while in the third replicate 16.9% was scored as WT. Lower proportions systematically showed a WT sequence only (‘a’ nucleotide). Careful manual inspection revealed the presence of additional small peaks distinguishable from background in two cases (11.7% and 16.9%), but not in any of the suspensions with <10% mutants. On average, Sanger sequencing required 15.9% (14.2–17.6) mutant bacteria for detecting the resistant population.

Targeted NGS (cluster density: 227 K/mm2; clusters passing filter: 85.5%; ≥Q30: 91.4%; sequence depth >6250 reads) proved to be sensitive enough in detecting heteroresistance in all mixtures (Table 1). Notably, background noise of 0.23% to 0.35% was observed in the R0S100 and H37Rv controls, which may partially explain the overall slightly higher mutant proportions in targeted NGS compared to ddPCR (Table 1; Fig. 2). Nonetheless, observed NGS and ddPCR proportions were tightly correlated.

Discussion

Overall, pDST and targeted NGS assays achieved the highest sensitivity in detecting gatifloxacin heteroresistance whereas MTBDRsl had an LOD around 5% and Sanger sequencing would consistently detect mutants >15%.

While ddPCR results revealed variability among experimentally prepared mixtures used in this study - possibly resulting from pipetting errors or incomplete homogenisation of the mother suspensions - the observed variability among biological triplicate tests was overall within the criteria of acceptability, i.e. for each of the mixtures the intra-triplicate standard deviation was smaller than the intended value to measure.

Recently, the WHO endorsed 0.25 mg/L as critical concentration for gatifloxacin susceptibility testing in MGIT and 0.5 mg/L on Löwenstein-Jensen medium, but no recommendation was given for 7H11 agar medium16. Giannoni and colleagues reported all gyrA mutants to have a gatifloxacin MIC of ≥0.5 mg/L when tested on 7H11 agar17. Our MIC analysis showed that presence of 1 to 3.7% resistant bacilli was associated with an MIC of 0.5 mg/L, while higher mutant proportions resulted systematically in an MIC of 1 mg/L. Hence a breakpoint of 0.25 mg/L on 7H11 would allow to detect approximately 1% D94G mutants, while >5% mutants should be present to be detectable at 0.5 mg/L, favouring a critical concentration of 0.25 mg/L. This observation is consistent with the reported good performance of phenotypic DST to detect heteroresistance18,19, including to moxifloxacin20.

LPAs are much faster than pDST with results available in just one day when performed directly from a clinical specimen. Direct testing is not only faster, but also avoids selection bias through the culture process, in which one population may out-grow another one21. Although it should be considered that visual inspection of LPA strips in our study might have been potentially influenced by the prior knowledge of the involved mutant and expected banding profile, MTBDRsl (version 1 and 2) proved slightly less sensitive than phenotypic testing, detecting ~5% D94G mutants, in line with the reported LOD of heteroresistance for rifampicin and isoniazid using MTBDRplus18,19. Heteroresistance assessment by LPAs is hampered since it is limited to mutants for which a probe is available on the strip, leaving heteroresistance by other mutants undetectable. However, the five mutant probes incorporated in the Genotype MTBDRsl assays represent 83% of moxifloxacin resistant strains worldwide (A90V, S91P, D94A/N/Y/G/H)22, limiting the impact of this shortcoming. The FQ + KM TB II includes only three of these most prevalent mutations (A90V, D94G/A). In addition, the lower sensitivity of probe 2c decreases the ability to detect heteroresistance in case of combined D94G + S95T polymorphism. Finally, further investigation would be required to ascertain if LPA profiles from direct testing from clinical specimens will result in equally clear bands as those from indirect testing.

As shown previously for rifampicin, isoniazid and moxifloxacin18,19,20, Sanger sequencing was found to be less sensitive in detecting heteroresistance than pDST and LPAs, with the need for the presence of about 15% mutant bacilli to detect heteroresistance using common softwares. On the other hand, sequencing has the advantage that it can detect all genetic variants in the sequence under investigation, and the technique is widely implemented in reference laboratories. Manual re-investigation of the Sanger chromatograms further improved the LOD to 10–15%. Such manual reading is however rather subjective and time consuming.

NGS offers new opportunities to provide comprehensive information for surveillance and clinical management of drug-resistant TB23,24,25. Daum and colleagues identified FQ heteroresistance in 15% of the M. tuberculosis isolates by whole genome sequencing (WGS), even with an average reproducible coverage depth of around 30x26. Deep targeted sequencing generates more copies per position compared to standard WGS, increasing the probability of detecting minority populations9,27. Our current findings confirm that ultra-deep sequencing (>5000x) is suitable to detect as little as 1% of resistant bacteria in a mixed population. However, since our study was limited to the analysis of just D94G, it remains to be proven that NGS would have equivalent performance for other mutants.

In general, all approaches tested provided more accurate estimates for FQ heteroresistance compared to melting temperature assays using molecular beacons or dual-labelled probes, previously reported to require for detection of heteroresistance 10–70% and 30–100% of mutants, respectively28. GeneXpert MTB/RIF Ultra – using melting curves to detect rifampicin resistance – can detect 5–40% mutants depending on the mutation type29.

The clinical importance of heteroresistance is likely substantial, akin to’fixed‘ (100%) resistance. The proportion method for pDST, which has been around for over half a century, by design, tests for ≥1% resistant subpopulations, with strong predictive value for poor treatment outcome, at least for the core drugs like FQs and rifampicin30. High-level FQ resistance has been associated with poor treatment outcome31,32, and specific gyrA mutations like D94G predict poor outcome32. In the same study, software based Sanger sequencing detected heteroresistance in 9.2% of gyrA/B mutants32. While the sample size was too small to identify treatment outcome differences between heterogeneous versus homogenous populations, their MIC levels fell in the same range, which is in agreement with the current MIC findings. Taken together, this implicates that any (molecular) detection of ≥1% heteroresistance, is probably key (for core drugs), notwithstanding the lack of direct evidence on clinical impact.

In conclusion, targeted NGS analysis reached an LOD of at least 1% mutant variants, equalling the 1% critical concentration applied for pDST, whereas LPAs and Sanger sequencing required higher mutant proportions to be detectable (5% and 15% respectively). Their direct application on (heteroresistant) clinical samples requires further evaluation. Based on indirect testing, our findings suggest that targeted deep sequencing may become the gold standard for the detection of heteroresistance directly in clinical samples. The LOD of direct testing, including on samples with low bacterial burden such as Xpert-positive microscopy-negative samples, will need to be determined in future studies, including the clinical relevance of small proportions of mutant populations.

Methods

Experimentally mixed populations

FQ resistance in M. tuberculosis is mainly caused by mutations in the FQ-resistance determining regions in the gyrA and gyrB genes, encoding for DNA gyrase, the target of FQs22. Two isogenic strains were used to minimize bias by inter-strain variability: a pan-susceptible mother strain with a phylogenetic polymorphism in gyrA (ITM 011738, S; gyrA agc95acc (S95T) and gyrB WT) and it’s in vitro selected ofloxacin-resistant daughter showing in addition a gyrA gac94ggc D94G mutation (ITM 130481) (see web-only See web-only Supplementary M&M). D94G was chosen as it represents 21–32% of FQ-associated mutations in clinical isolates and has been related to high MICs, negatively impacting MDR-TB treatment outcome32. For each strain, a 1 mg/mL bacterial suspension was prepared by transferring colonies from 3-weeks old Löwenstein-Jensen slants in sterile 0.01% Tween80 solution, followed by 1 minute vortexing, as per laboratory’s routine practice. Homogeneous suspensions were mixed in the following proportions (R%S%): R0S100, R1S99, R5S95, R10S90, R20S80, R30S70, R40S60, R50S50, R100S0. These suspensions were prepared thrice on different days to generate biological triplicates allowing to determine reproducibility of results (Fig. 2). The H37Rv M. tuberculosis reference strain (BCCM/ITM 083715) was included as control in each experiment.

To check the mutant/WT proportion in each of the mixtures and replicates, droplet ddPCR analysis was performed on a QX100 ddPCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using PrimePCR Custom Assay hydrolysis probes (See web-only Supplementary M&M; See web-only Supplementary Fig. 1).

MIC determination

The MIC for gatifloxacin was determined on Middlebrook 7H11 agar medium at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mg/L after three and six weeks of incubation as described before32. A difference of 1 dilution in MIC values among triplicates was considered acceptable.

Heat inactivation

DNA extraction by heat inactivation was performed as previously described32. Heat inactivated suspensions were shipped by courier at ambient temperature from Antwerp (Belgium) to Milan (Italy) for targeted NGS and ddPCR.

Sanger sequencing of the gyrA and gyrB genes

Amplification of gyrA and gyrB was done as described33. An isolate was defined as heteroresistant if both WT nucleotides and mutant nucleotides conferring resistance at a specific locus were detected, either by the CLC Sequence Viewer software (version 7.0.1) calling ‘ambiguous’ nucleotides like ‘R’ representing the simultaneous detection of a and t nucleotides, or by blinded manual re-inspection of the chromatograms using Finch TV (version 1.4.0) (Geospiza Inc.) (Fig. 3). For the manual interpretation, we only considered peaks that were centered under the main peak and of which the height exceeded background noise (See web-only Supplementary M&M).

Examples of Sanger sequence analysis from the gyrA gene for experimentally mixed strains, representing the reverse string. Left: automated software interpretation (limit of detection for FQ heteroresistance = 20%) Right: manual interpretation showing a double peak that remained undetected by the software (limit of detection = 10%). R10S90 = 10% mutant bacilli + 90% susceptible bacilli; R20S80 = 20% mutant bacilli + 80% susceptible bacilli; RS100 = 100% susceptible bacilli; R100S0 = 100% mutant bacilli.

GenoType MTBDRsl (version 1, Hain Lifescience, Germany) and GenoScholar-FQ + KM TB II (Nipro, Japan)

DNA amplification and hybridization were done according to the manufacturers’ instructions using the Twincubator (MTBDRsl) or Multiblot NS-4800 (FQ + KM TB II providing a fully automated hybridization process). To document non-inferiority of the newly released version 2 of the MTBDRsl, one set of samples was repeated. The LPA profile readout was performed manually by two readers. In case of heteroresistance with a D94G mutation, the MUT3C band in MTBDRsl and all WT bands of the gyrA gene had to be visible, whereas complete resistance would result in the absence of WT3 in presence of MUT3C, and complete susceptibility in the absence of MUT3C in presence of all WT bands (Fig. 4A). Similar profiles would be obtained for the FQ + KM TB II, yet with the 2c band reacting, representing the combined D94G and S95T polymorphism (Fig. 4B). To challenge the 2a probe – representing the D94G mutation alone – another set of mixtures with a WT strain (H37Rv) and a D94G mutant (ITM 102197) was tested once with the FQ + KM TB II.

Examples of MTBDRsl (V1) (A) and Genoscholar FQ + KM TB II (B) strips from experimentally mixed strains, showing a limit of detection of 5% resistant bacilli (WT + MUT band present). The Genoscholar FQ + KM TB II strips show the results of the mixtures with an isolate containing the D94G mutant, yet not having the S95T polymorphism. WT = wildtype; MUT = mutant; R5S95 = 5% mutant bacilli + 95% susceptible bacilli; RS100 = 100% susceptible bacilli; R100S0 = 100% mutant bacilli.

Illumina targeted NGS

A fraction of the gyrA gene including the QRDR (genomic coordinates: 7077-7721; amplicon length: 645 bp) was amplified using a standard amplification protocol (See web-only Supplementary M&M).

Data Availability

Upon request, materials or information described in this study can be made available without restrictions, apart from the experimental mixtures that have been used almost entirely for these and additional analysis.

References

Rinder, H., Mieskes, K. T. & Löscher, T. Heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 5, 339–345 (2001).

Zetola, N. M. et al. Mixed Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex infections and false-negative results for rifampin resistance by GeneXpert MTB/RIF are associated with poor clinical outcomes. J Clin Microbiol 52, 2422–2429 (2014).

Streicher, E. M. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis population structure determines the outcome of genetics-based second-line drug resistance testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 2420–2427 (2012).

Canetti, G. et al. Advances in techniques of testing mycobacterial drug sensitivity, and the use of sensitivity tests in tuberculosis control programmes. Bull World Health Organ 41, 21–43 (1969).

Mokrousov, I. et al. Molecular characterization of ofloxacin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from Russia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 2937–2939 (2008).

Hillemann, D., Rüsch-Gerdes, S. & Richter, E. Feasibility of the GenoType MTBDRsl assay for fluoroquinolone, amikacin-capreomycin, and ethambutol resistance testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 47, 1767–1772 (2009).

Eilertson, B. et al. High proportion of heteroresistance in gyrA and gyrB in fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 3270–3275 (2014).

An, D. D. et al. Beijing genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is significantly associated with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Vietnam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53, 4835–4839 (2009).

Operario, D. J. et al. Prevalence and extent of heteroresistance by next generation sequencing of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. PLoS One 12, e0176522 (2017).

Singhal, R. et al. Sequence analysis of fluoroquinolone resistance-associated genes gyrA and gyrB in clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients suspected of having multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol 54, 2298–2305 (2016).

Chiang, C. Y., Van Deun, A. & Rieder, H. L. Gatifloxacin for short, effective treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. (Perspective). Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 20, 1143–1147 (2016).

Bunz, F. et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest 104, 263–9 (1999).

Hindson, C. M. et al. Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nat Methods 10, 1003–5 (2013).

Pholwat, S., Stroup, S., Foongladda, S. & Houpt, E. Digital PCR to detect and quantify heteroresistance in drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 8(2), e57238, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057238 (2013).

Taylor, S. C., Carbonneau, J., Shelton, D. N. & Boivin, G. Optimization of Droplet Digital PCR from RNA and DNA extracts with direct comparison to RT-qPCR: Clinical implications for quantification of Oseltamivir-resistant subpopulations. Journal of Virological Methods 224, 58–66 (2015).

World Health Organization. Technical report on critical concentrations for drug susceptibility testing of medicines used in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. World Health Organization Document WHO/CDS/TB/2018.5, 1–106 (2018).

Giannoni, F. et al. Evaluation of a new line probe assay for rapid identification of gyrA mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49, 2928–33 (2005).

Bek Folkvardsen, D. et al. Can molecular methods detect 1% isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol 51, 1596–1599 (2013).

Folkvardsen, D. B. & Thomsen, V. Ø. Rifampin heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures as detected by phenotypic and genotypic drug susceptibility test methods. J Clin Microbiol 51, 4220–4222 (2013).

Bernard, C. et al. In vivo Mycobcacterium tuberculosis fluoroquinolone resistance emergence: a complex phenomenon poorly detected by current diagnostic tests. J Antimicrob Chemother 71, 3465–3472 (2016).

Metcalfe, J. Z. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis subculture results in loss of potentially clinically relevant heteroresistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61, e00888–17 (2017).

Avalos, E. et al. Frequency and geographic distribution of gyrA and gyrB mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates: a systematic review. PLoS One 10, e0120470 (2015).

Papaventsis, D. et al. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for detection of drug resistance: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect 23, 61–68 (2017).

Zignol, M. et al. Population-based resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to pyrazinamide and fluoroquinolones: results from a multicountry surveillance project. Lancet Infect Dis 16, 1185–1192 (2016).

Tagliani, E. et al. Culture and next-generation sequencing-based drug susceptibility testing unveil high levels of drug-resistant-TB in Djibouti: results from the first national survey. Sci Rep 7, 17672 (2017).

Daum, L. T. et al. Next-generation sequencing for characterizing drug resistance-conferring Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes from clinical isolates in the Ukraine. J Clin Microbiol 56, e00009–18 (2018).

Trauner, A. et al. The within-host population dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis vary with treatment efficacy. Genome Biol 18, 71 (2017).

Roh, S. S. et al. Comparative evaluation of sloppy molecular beacon and dual-labeled probe melting temperature assays to identify mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis resulting in rifampin, fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance. PLoS One 10, e0126257 (2015).

Chakravorty, S. et al. The new Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra: improving detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and resistance to rifampin in an assay suitable for point-of care testing. mBio 8, e00812–17 (2017).

Van Deun, A. et al. Principles for constructing a tuberculosis treatment regimen: the role and definition of core and companion drugs. (Perspective). Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 22, 239–245 (2018).

Aung, K. J. M. et al. Successful ‘9-month Bangladesh regimen’ for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among over 500 consecutive patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 18, 1180–1187 (2014).

Rigouts, L. et al. Specific gyrA gene mutations predict poor treatment outcome in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 71, 314–323 (2016).

Von Groll, A. et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and mutations in gyrA and gyrB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53, 4498–4500 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Damien Foundation, Belgium. BdJ and LR were supported by a European Research Council Starting Grant INTERRUPTB (311725). The in vitro selected mutant was generated by Nele Coeck, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. Genoscholar FQ + KM TB II kits were kindly provided by NIPRO (Japan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R., B.d.J. and M.S. designed and coordinated the study. M.S., P.d.R. and P.L. performed the M.I.C., L.P.A. and Sanger sequence assays. P.M., A.C., S.G., V.L. and D.M.C. designed and performed the ddPCR and N.G. assays. All authors contributed to data analysis, manuscript drafting and reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rigouts, L., Miotto, P., Schats, M. et al. Fluoroquinolone heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: detection by genotypic and phenotypic assays in experimentally mixed populations. Sci Rep 9, 11760 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48289-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48289-9

This article is cited by

-

Mixed infections in genotypic drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Antibiotic heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials (2021)

-

Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance against fluoroquinolones in the northeast of Iran

BMC Infectious Diseases (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.