Abstract

p16Ink4a/CDKN2A is a tumor suppressor that critically regulates the cell cycle. Indeed, p16Ink4a deficiency promotes tumor formation in various tissues. We now report that p16Ink4a deficiency in female mice, but not male mice, induces leanness especially in old age, as indicated by lower body weight and smaller white adipose tissue, although other major organs are unaffected. Unexpectedly, the integrity, number, and sizes of adipocytes in white adipose tissue were unaffected, as was macrophage infiltration. Hence, hypermobility appeared to be accountable for the phenotype, since food consumption was not altered. Histological analysis of the cerebellum and deep cerebellar nuclei, a vital sensorimotor control center, revealed increased proliferation of neuronal cells and improved cerebellum integrity. Expression of estrogen receptor β (ERβ) and PCNA also increased in deep cerebellar nuclei, implying crosstalk between p16Ink4a and ERβ. Furthermore, p16Ink4a deficiency expands LC3B+ cells and GFAP+ astrocytes in response to estrogen. Collectively, the data suggest that loss of p16INK4a induces sexually dimorphic leanness in female mice, which appears to be due to protection against cerebellar senescence by promoting neuronal proliferation and homeostasis via ERβ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Appropriate control of stem/progenitor cell proliferation is essential to maintain tissue homeostasis in multicellular organisms1 and prevent tumor formation. On the other hand, loss of stem/progenitor cell proliferation is implicated in aging and senescence. Although recent medical advances have remarkably extended human life span, there are still challenges to address, including age-associated degenerative diseases like atherosclerosis2, diabetes3, macular degeneration4, osteoporosis5, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease6 and Alzheimer’s disease7, both of which are barely reversible.

p16Ink4a/CDKN2A regulates the cell cycle by slowing the progression from G1 to S phase8. For example, p16Ink4a binds cyclin-dependent kinase 4/69 to induce retinoblastoma-dependent cell-cycle arrest and prevent tumor progression. p16Ink4a is expressed at low levels in normal cells, but is induced by tumorigenic stimuli, and is progressively accumulated with age10,11, correlating with reduced proliferative capacity in various tissues12,13,14. These findings imply that cellular senescence due to p16Ink4a is closely linked to decreased proliferation of stem/progenitor cells. On the other hand, ablation of p16Ink4a induces spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice and increases sensitivity to carcinogens15,16. Indeed, p16Ink4a is one of the most frequently inactivated genes in human cancers along with p5317,18. Hence, p16Ink4a appears to be a key regulator of tissue homeostasis.

Sexual dimorphism is the systemic difference in phenotype between males and females19. Accordingly, the effects of modifying a sexually dimorphic gene may appear predominantly in only one sex. For example, estrogen, a steroid hormone and the major female sex hormone, is essential for the development and regulation of the female reproduction system. However, estrogen also affects numerous cell processes20,21, including neuronal development, as has been documented for years22. Many of these effects are mediated by estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor β (ERβ), which are also regulators of neuronal processes such as Purkinje cell differentiation and expression of neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor23,24. Indeed, ERβ knockout mice exhibit impaired spatial learning, neuronal migration, and increased apoptosis25. Importantly, estrogen therapy initiated at onset of menopause reduces the risk or delays the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in women26,27, suggesting a protective role against neurodegeneration.

We now report that p16Ink4a-deficient female mice gain less weight and accumulate smaller white adipose tissue, effects that became more pronounced with age. These effects are absent from male mice, indicating sexual dimorphism in p16Ink4a activity, probably via crosstalk with estrogen receptors. We also investigated the underlying mechanisms, with a view to characterize this previously unreported function of p16Ink4a.

Results

p16Ink4a deficiency suppresses weight gain in female mice

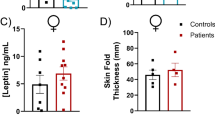

By measuring the weight of p16Ink4a−/− (p16−/−) FVB mice and littermates (p16+/+) at 4–35 weeks from birth, we found that ablation of p16Ink4a suppresses weight gain in female but not male mice. This effect became more pronounced with age (Fig. 1A, left panel), and was also observed in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1A, right panel). In addition, spontaneous proliferating lesions were more frequent in 1 year-old p16−/− mice (Supplemental Table S1), as verified by a blinded pathologist, and in agreement with previous reports demonstrating that p16Ink4a deletion deregulates the cell cycle and promotes tumorigenesis28. However, food intake was comparable between p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB mice at 8 weeks (before weight differences were observed), 18 weeks (at the time weight differences were observed), and 52 weeks (after body weights started to differ) (Fig. 1B), indicating that p16Ink4a deficiency does not induce anorexia due to tumor growth. Blood chemistry data show that p16Ink4a deficiency induces some metabolic changes in 1 year old male but not female mice (Fig. 1C). In addition, most organs, including the brain, liver, kidney, spleen, lung, heart, and brown adipose tissue, were comparable in weight in 1 year-old p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice, but white adipose tissues were dramatically lighter in female but not male p16−/− mice (Fig. 1D,E).

p16Ink4a deficiency inhibits weight gain in female mice of different genetic backgrounds. (A,B) p16+/+ and p16−/− male and female mice were weighed weekly at 4 to 35 weeks while housed specific pathogen-free on diets of 25% protein, 13% fat, and 62% carbohydrates (A). Food intake per mouse was measured at 8, 18, and 52 weeks (B) (n = 5). (C) Blood chemistry analysis of sera from 1 year old p16+/+ and p16−/− male and female mice (n = 9). (D,E) p16+/+ and p16−/− male and female mice were sacrificed at 1 year, and the brain, liver, kidney, spleen, lung, heart, white adipose tissue, brown adipose tissue, and total body were weighed D (n = 5–9). Mice were also imaged after opening the abdominal cavity (E,A,B,D) data are representative of three independent experiments. Results are mean ± SD.

p16Ink4a depletion does not affect adipose tissue physiology

Since estrogen is a major regulator of adipose tissue in female animals29, we examined whether p16Ink4a depletion may affect the expression of estrogen receptors or the number of cells expressing estrogen receptors. Thus, paraffinized sections of white adipose tissue from 1 year-old p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were immunohistochemically stained with antibodies to ERα and ERβ. While ERα-expressing cells were not detected (Fig. 2A, left), ERβ-expressing cells were found throughout the entire tissue section. However, the number of ERβ+ cells was comparable between p16+/+ and p16−/− mice of both sexes (Fig. 2A, right). F4/80+ macrophages, which infiltrate adipose tissues in obese organisms and are significantly and positively correlated with adipocyte size30, were also comparable in number between p16+/+ and p16−/− mice (Fig. 2B). In addition, adipocytes are similar in size among all animals (Fig. 2C), indicating that p16Ink4a deficiency does not affect adipose tissues per se.

p16Ink4a deficiency does not alter homeostasis in white adipose tissue. (A) White adipose tissues from p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were stained with anti-ERα (left panel) and anti-ERβ (right panel). ERβ+ cells (brown) were quantified at high power (n = 15). (B) Number of F4/80+ cells (brown) (n = 15). (C) Adipocyte size (n = 15). HPF, high power field. Results are mean ± SD.

p16Ink4a deficiency promotes neural cell proliferation in female mice

We observed that female p16−/− mice are hyperactive in comparison to female p16+/+ mice. Indeed, movement tracking for 3 min revealed that the former moved across 2-fold longer distance than the latter, suggesting that p16Ink4a deficiency may be linked to hypermobility in females. In contrast, mobility was comparable in male p16+/+ and p16−/− mice (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 1).

Mouse mobility and distribution of estrogen receptors in the cerebellum. (A) Movements of 1 year-old p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB mice were tracked by video for 3 min in a test cage (left images) and total distances were calculated (right graph) (n = 8). (B,C) Cerebellum sections from p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were stained with anti-ERα (B) or anti-ERβ (C) and ERβ+ cells (brown) were quantified (n = 15). HPF, high power field. Results are mean ± SD.

ERα-expressing cells were observed by immunohistochemistry in the thalamus (Supplemental Fig. 2) but not in the cerebellum, which coordinates motor activities31 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, ERβ-expressing cells were pervasive throughout the cerebellum, including in the molecular and granular layer and in deep cerebellar nuclei (Fig. 3C). ERβ+ cells were more abundant in female (~27 cells/high-power field in the molecular and granular layer, ~18 cells/high-power field in deep cerebellar nuclei) than in male mice (~18 cells/high-power field in the molecular and granular layer, ~12 cells/high-power field in deep cerebellar nuclei), but comparable between p16+/+ and p16−/− male mice (Fig. 3C). However, ERβ+ cells were more abundant in female p16−/− mice. In addition, cells expressing proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker of proliferation, were significantly more abundant in the same tissues in female p16−/− mice than in female p16+/+ mice at 18 and 52 weeks (Fig. 4A), even though comparable in number among all male mice. Similarly, cells expressing Ki67, also a marker of proliferation, accumulated at all time points examined in female p16−/− mice only (Fig. 4B). Finally, double immunofluorescence staining indicated that ERβ+ PCNA+ cells in deep cerebellar nuclei were significantly more abundant in p16−/− female mice than in wild type female mice, but comparable among all male mice (Fig. 5), suggesting that suppression of p16Ink4a enhances mobility in female mice, possibly via estrogen-associated neural cell proliferation.

p16Ink4a deficiency promotes proliferation of neural cells in the cerebellum of female mice only. (A,B) Cerebellum sections from p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were stained with anti-PCNA (A, n = 15) and anti-Ki67 (B, n = 9–15), and stained cells in the cerebellum and in deep cerebellar nuclei (brown) were counted in Image J as red dots in a gray background. HPF, high power field. Results are mean ± SD.

Estrogen signaling promotes the proliferation of neural cells in deep cerebellar nuclei region of female p16Ink4a knockout mice. Sections of deep cerebellar nuclei from p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were stained with anti-ERβ (red) and anti-PCNA (green) to quantify ERβ+ PCNA+ cells/field. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) (n = 15–21). Results are mean ± SD.

p16Ink4a deficiency protects female cerebella from aging-associated deterioration

We investigated whether p16Ink4a deficiency may protect the cerebellum from deterioration, which is typically associated with age or neurodegeneration32. Loss of p16Ink4a slightly expanded the granular layer, although the size of the entire cerebellum was not affected (Fig. 6A). In addition, astrocytes, the major cell type that maintains brain integrity33, were more abundant in the deep cerebellar nuclei region of p16−/− mice, as assessed by staining for GFAP (Fig. 6B, white dotted line). Nevertheless, p16Ink4a deficiency did not enhance astrocyte proliferation as assessed by staining for PCNA (Supplemental Fig. 3).

p16Ink4a regulates senescence in the cerebellum. (A) Size of the granular (GL) and molecular layer (ML) in the cerebellum of p16+/+ and p16−/− female FVB mice (n = 15). (B) Sections of deep cerebellar nuclei from p16+/+ and p16−/− female FVB mice were stained with anti-GFAP, and GFAP+ cells (brown, black arrow head) were quantified at high power (right panel) (n = 9). (C) Cerebellum sections from p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB male and female mice were stained with anti-LC3B, and LC3B+ cells (brown) were counted in ImageJ as red dots in a gray background (n = 15). HPF, high power field. Results are mean ± SD.

Autophagy, which is essential for survival of neural cells and is impaired in neurodegenerative disorders and during senescence34,35, is more robust in p16−/− female mice than in female p16+/+ mice, as suggested by the accumulation of LC3B+ cells in the deep cerebellar nuclei region (~19 cells/high-power field in p16+/+, ~27 cells/high-power field in p16−/−). However, autophagy was comparable among male mice (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that p16Ink4a deficiency may protect the cerebellum by activating autophagy.

Discussion

We found that deletion of p16Ink4a, a cell cycle regulator, attenuates age-associated obesity in female mice by inducing hypermobility. Protection against deterioration of the cerebellum, a motor center, appears to be essential to this phenotype, since ablation of p16Ink4a promotes neuronal cell proliferation and increases autophagic cells and astrocytes in this region of the brain. However, p16Ink4a deficiency was not similarly beneficial in male mice, presumably as a result of sexual dimorphism, as seen in many different phenotypes19,36. The dimorphism is likely mediated by estrogen, which is essential to female development but which also regulates brain development and homeostasis, especially in females. Estrogen receptors are also more abundantly expressed in the female brain than in the male brain37, in line with our results.

In specific pathogen-free breeding, mice consume feed continuously in confined spaces with little mobility, such that the abdominal cavity becomes full of fat in most of these mice after a year or so. Remarkably, this phenomenon was not observed in p16Ink4a -deficient female mice. Hence, we hypothesized that ablation of p16Ink4a may affect the development of white adipose tissue or induce metabolic changes. However, we did not find differences in the number of adipocytes expressing estrogen receptors, the size of adipocytes, and the number of infiltrating F4/80+ macrophages, which is significantly and positively correlated with both adipocyte size and body weight30. Therefore, ablation of p16Ink4a has little effect on adipocyte metabolism. On the other hand, senescence of the cerebellum reduces motility, which can also lead to obesity38,39. Remarkably, we found that suppression of p16Ink4a increases proliferation of neuronal cells, delays senescence in the cerebellum, and enhances mobility. In addition, p16−/− female mice were also more responsive to peripheral stimulation than wild type (data not shown).

Homeostasis is critical in the brain, an organ with less proliferation but longer cell life, than in other tissues. GFAP+ astrocytes, which regulate neurotransmitter trafficking and recycling, ion homeostasis, energy metabolism, and defense against oxidative stress to maintain brain homeostasis33, were significantly more abundant in the former (Fig. 6B). Also, autophagy is an important process where age-related loss of autophagy accelerates the progression of neurodegenerative disease due to accumulation of toxic protein aggregates in neurons40, and LC3 was also highly expressed on astrocytes41. Furthermore, neural stem cells (NSCs) are required for generating neural cell, and autophagy plays an important role in stemness and neurogenesis of NSCs42,43. Notably, LC3+ neurons were more abundant in the deep cerebellar nuclei region of p16−/− female mice than in wild type female mice (Fig. 6C). We also found that ERβ+ cells and proliferating ERβ+ cells were increased in p16−/− female (Figs 3 and 5). ERβ is important for maintaining neural homeostasis; in fact, ERβ deficiency in adult mouse has shown increased vulnerability to neurodegeneration44. In addition, ERβ signaling is important for differentiation of neuronal precursors45.

Therefore, there are two possibilities for the increased LC3+ cells in p16−/− condition: (1) promoted proliferation of ERβ+ NSCs, which were highly expressed in LC3, and (2) increased ERβ+ neural progenitor cells were differentiated into neuronal cells, such as LC3+ astrocyte, in response to estrogen signal following the loss of p16Ink4a. We need to further identify the role of the stem, progenitor, or differentiated neuron cells controlled by p16Ink4a in response to estrogen.

As previously reported, loss of p16Ink4a clearly induces development of sporadic cancers. However, tumors develop only after a considerable amount of time even if p16Ink4a is mutated, so modulating p16Ink4a at an advanced age to prevent dementia may still prove beneficial on balance. Alternatively, neuron-specific regulation of p16Ink4a and enhanced estrogen signaling may help overcome various neurological diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yonsei University (IACUC number: 2015–0116) and were compliant with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. FVB and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, maintained in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility under a 12 h light cycle, and provided PicoLab® Rodent Diet 20 (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO USA).

TALENs were designed to cleave downstream of the p16Ink4a start codon to introduce frameshift mutations and thus knock out the gene. Plasmids encoding left- and right-TALENs that recognize the p16Ink4a sequences 5′-TGCATGACGTGCGGGCACTG-3′ and 5′-GTTTCGCCCAACGCCCCGAA-3′, respectively, were obtained from ToolGen. TALEN mRNAs were synthesized using mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and diluted in buffer containing 0.25 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris pH 7.4 and pretreated with diethyl pyrocarbonate. These mRNAs were injected at 50 ng/μL into the cytoplasm of one-cell embryos using a piezo-driven manipulator (Prime Tech, Tsuchiura, Japan), as previously described46. Subsequently, embryos were transferred into foster mothers to generate F0 mice, which were screened by PAGE-PCR as previously described47, using genomic DNA obtained from newborns. PCR products of candidate knockout mice were then cloned in T-Blunt PCR Cloning Vector (SolGent, Deajeon, South Korea), and mutations were validated by direct sequencing (Cosmogenetech, Seoul, South Korea). Mice with the earliest premature stop codons were selected as p16Ink4a knockout strain.

p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB or C57BL/6 mice were maintained by crossing with p16+/− × p16+/−. Four weeks after birth, offspring were separated from mother cage and genotyped with the following primers: 5′-GAGGAGAGCCATCTGGAG-3′ and 5′-CCTTGCCTACCTGAATCG-3′. p16+/+ was amplified to 153 base pair and p16−/− was amplified to 133 bp after PCR reaction.

Antibodies

Antibodies to F4/80 (Cat no: ab6640), Ki67 (Cat no: ab16667), LC3B (Cat no: ab48394), GFAP (Cat no: ab7260) were obtained from Abcam. Antibodies to ERα (Cat no: sc-390244) and PCNA (Cat no: sc-56) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, while anti-ERβ (Cat no: PA1-310B) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Assessment of mouse mobility

Mouse mobility was assessed according to Cho et al.48. Briefly, male and female p16+/+ and p16−/− FVB mice were placed in standard polypropylene rodent breeding cages with standard-depth wood chip bedding, and which were not covered during experiments to prevent internal saturation with odorants. A video camera (HD lens 720P 30FPS Auto Widescreen) was fixed vertically about 1 m above the cage and linked to a Smart 3.0 video-tracking system (Harvard apparatus©, Holliston, MA USA). Mouse behavior was recorded and automatically tracked for 3 min.

Blood chemistry

One-year old p16+/+ and p16−/− male and female FVB mice were sacrificed using by CO2 gas, and total blood was immediately obtained from the heart using 26G 1 ml syringe. To isolate serum form of total blood, blood samples were placed in the MiniCollect® tube (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria) and centrifugation 1 × 104 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. Sera (10 μL) from 1 year-old p16+/+ and p16−/− male and female FVB mice were analyzed on a DRI-chem 4000i (Fuji, Minato, Japan) automated clinical chemistry analyzer to quantify changes in albumin (ALB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol (TCHO), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total bilirubin (TBIL).

Food intake

Each of the two mice groups were bred in a single cage, and were supplied with 200 g of PicoLab® Rodent Diet 20. We measured the amount of food left on a digital scale, and the amount of reduced food was defined as the amount of food the mice ingested. The measurement was performed every other day for two weeks, and the results were converted to the amount of food consumed per week. The amount of food powder that fell to the bottom of the cage was negligible in this measurement, since its amount had no significant effect on the result.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

For immunohistochemistry, tissues were fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and mounted in paraffin blocks by conventional methods. Samples were sectioned at 3 μm, deparaffinized with xylene three times for every 20 min, 100% EtOH three times for every 10 min, 90% EtOH two times for every 10 min, and 75% EtOH for 10 min, and then rehydrated in PBS. Antigens were then retrieved for 15 min at high pressure in Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA). Subsequently, specimens were chilled on ice for 1 h, washed with PBS three times for 5 min, and blocked with 3% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxidase. Slides were washed again with PBS, blocked for 2 h at room temperature with Serum-Free Protein Block (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA), probed at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies (1/1 000 dilution), stained for 30 min with anti-mouse (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA) or anti-rabbit IgG (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, and developed with Liquid DAB + Substrate Chromogen System (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA). Finally, specimens were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Dako, Santa Clara, CA USA) and mounted with Shandon Synthetic Mount (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA).

For immunofluorescence, tissues samples were blocked as described, probed at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies (1/1 000 dilution), labeled for 2 h with anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) or with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to cyanine5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), and stained with DAPI for 15 min. Finally, slides were mounted with ProLong™ Gold antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), imaged on an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and analyzed using Zeiss Zen Blue Edition.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between the two groups was determined by unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and significance was designated with asterisks (N.S., not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). All data were evaluated in GraphPad Prism version 7.0d (GraphPad, San Diego, CA USA) for statistical analyses.

References

Biteau, B., Hochmuth, C. E. & Jasper, H. Maintaining Tissue Homeostasis: Dynamic Control of Somatic Stem Cell Activity. Cell Stem Cell 9, 402–411 (2011).

Conti, P. & Shaik-Dasthagirisaeb, Y. Atherosclerosis: a chronic inflammatory disease mediated by mast cells. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 380–386 (2015).

Vlassara, H., Bucala, R. & Striker, L. Pathogenic Effects of Advanced Glycosylation - Biochemical, Biologic, and Clinical Implications for Diabetes and Aging. Lab. Invest. 70, 138–151 (1994).

Klein, R. J. et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308, 385–389 (2005).

Riggs, B. L. et al. Differential Changes in Bone-Mineral Density of the Appendicular and Axial Skeleton with Aging - Relationship to Spinal Osteoporosis. J. Clin. Invest. 67, 328–335 (1981).

Wakabayashi, K. & Takahashi, H. Neuropathology of autonomic nervous system in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. Neurol. 38, 2–7 (1997).

Pratico, D. & Delanty, N. Oxidative injury in diseases of the central nervous system: Focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Med. 109, 577–585 (2000).

Ausserlechner, M. J., Obexer, P., Geley, S. & Kofler, R. G1 arrest by p16INK4A uncouples growth from cell cycle progression in leukemia cells with deregulated cyclin E and c-Myc expression. Leukemia 19, 1051–1057 (2005).

Serrano, M., Hannon, G. J. & Beach, D. A New Regulatory Motif in Cell-Cycle Control Causing Specific-Inhibition of Cyclin-D/Cdk4. Nature 366, 704–707 (1993).

Krishnamurthty, J. et al. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1299–1307 (2004).

Nelson, J. A. E. et al. Expression of p16INK4a as a biomarker of T-cell aging in HIV-infected patients prior to and during antiretroviral therapy. Aging Cell 11, 916–918 (2012).

Janzen, V. et al. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16(INK4a). Nature 443, 421–426 (2006).

Krishnamurthy, J. et al. p16(INK4a) induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature 443, 453–457 (2006).

Molofsky, A. V. et al. Increasing p16(INK4a) expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature 443, 448–452 (2006).

Serrano, M. et al. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell 85, 27–37 (1996).

Krimpenfort, P., Quon, K. C., Mooi, W. J., Loonstra, A. & Berns, A. Loss of p16(Ink4a) confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature 413, 83–86 (2001).

Hall, M. & Peters, G. Genetic alterations of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, and Cdk inhibitors in human cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 68, 67–108 (1996).

Hainaut, P. et al. Database of p53 gene somatic mutations in human tumors and cell lines: Updated compilation and future prospects. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 151–157 (1997).

Karp, N. A. et al. Prevalence of sexual dimorphism in mammalian phenotypic traits. Nat. Commun. 8, 15475 (2017).

McDevitta, M. A. et al. New insights into the classical and non-classical actions of estrogen: Evidence from estrogen receptor knock-out and knock-in mice. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 290, 24–30 (2008).

Mermelstein, P. G. Membrane-Localised Oestrogen Receptor alpha and beta Influence Neuronal Activity Through Activation of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. J. Neuroendocrinol. 21, 257–262 (2009).

Hedges, V. L., Ebner, T. J., Meisel, R. L. & Mermelstein, P. G. The cerebellum as a target for estrogen action. Front. Neuroendocrin. 33, 403–411 (2012).

Ikeda, Y. & Nagai, A. Differential expression of the estrogen receptors alpha and beta during postnatal development of the rat cerebellum. Brain Res. 1083, 39–49 (2006).

Tsutsui, K. Neurosteroids in the Purkinje cell: Biosynthesis, mode of action and functional significance. Mol. Neurobiol. 37, 116–125 (2008).

Wang, L., Andersson, S., Warner, M. & Gustafsson, J. A. Estrogen receptor (ER)beta knockout mice reveal a role for ER beta in migration of cortical neurons in the developing brain. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 703–708 (2003).

Zhao, L. Z. & Brinton, R. D. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca2+ dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1172, 48–59 (2007).

Zhao, L. Q. et al. 17 beta-Estradiol regulates insulin-degrading enzyme expression via an ER beta/PI3-K pathway in hippocampus: Relevance to Alzheimer’s prevention. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 1949–1963 (2011).

Sharpless, N. E., Ramsey, M. R., Balasubramanian, P., Castrillon, D. H. & DePinho, R. A. The differential impact of p16(INK4a) or p19(ARF) deficiency on cell growth and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 23, 379–385 (2004).

Cooke, P. S. & Naaz, A. Role of estrogens in adipocyte development and function. Exp. Biol. Med. 229, 1127–1135 (2004).

Weisberg, S. P. et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1796–1808 (2003).

Porras-Garcia, M. E., Ruiz, R., Perez-Villegas, E. M. & Armengol, J. A. Motor learning of mice lacking cerebellar Purkinje cells. Front. Neuroanat. 7, 4 (2013).

Cole, D. C. et al. Loss of APOBEC1 RNA-editing function in microglia exacerbates age-related CNS. pathophysiology. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13272–13277 (2017).

Belanger, M. & Magistretti, P. J. The role of astroglia in neuroprotection. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 11, 281–295 (2009).

Komatsu, M. et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 441, 880–884 (2006).

Plaza-Zabala, A., Sierra-Torre, V. & Sierra, A. Autophagy and Microglia: Novel Partners in Neurodegeneration and Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E598 (2017).

Kim, H. I., Lim, H. & Moon, A. Sex Differences in Cancer: Epidemiology, Genetics and Therapy. Biomolecules & Therapeutics 26, 335–342 (2018).

Orikasa, C., Kondo, Y., Hayashi, S., McEwen, B. S. & Sakuma, Y. Sexually dimorphic expression of estrogen receptor beta in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the rat preoptic area: Implication in luteinizing hormone surge. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3306–3311 (2002).

DeKorver, N. W., Lichty, D., van der Hart, M., Rassoulpour, A. & Bonasera, S. J. Increased whole cerebellar serotonin in aged C57BL/6 mice. Matters (Zur) 2017 (2017).

Asp, M., Simonsson, B., Larm, P. & Molarius, A. Physical mobility, physical activity, and obesity among elderly: findings from a large population-based Swedish survey. Public Health 147, 84–91 (2017).

Metaxakis, A., Ploumi, C. & Tavernarakis, N. Autophagy in Age-Associated Neurodegeneration. Cell 5, E37 (2018).

Jin, Y. C., Yang, S. F. & Zhang, X. H. Reduction of neuronal damage and promotion of locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury by early administration of methylprednisolone: possible involvement of autophagy pathway. Rsc. Adv. 7, 2979–2991 (2017).

Kempermann, G. & Gage, F. H. New nerve cells for the adult brain. Sci. Am. 280, 48–53 (1999).

Doetsch, F. A niche for adult neural stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 543–550 (2003).

Khalaj, A. J., Hasselmann, J., Augello, C., Moore, S. & Tiwari-Woodruff, S. K. Nudging oligodendrocyte intrinsic signaling to remyelinate and repair: Estrogen receptor ligand effects. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 160, 43–52 (2016).

Varshney, M. K. et al. Role of estrogen receptor beta in neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E10428–E10437 (2017).

Sung, Y. H. et al. Knockout mice created by TALEN-mediated gene targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 23–24 (2013).

Lee, J. H. et al. Differences between immunodeficient mice generated by classical gene targeting and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout. Transgenic Res. 27, 241–251 (2018).

Cho, H. J. et al. Newly developed method for mouse olfactory behavior tests using an automatic video tracking system. Auris Nasus Larynx 45, 103–110 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (NRF-2016M3A9D5A01952416, 2013M3A9D5072551), National Research Foundation grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2017R1A2B2009850, NRF-2017M3A9F3041234), by Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (14182MFDS978), and by Brain Korea 21 PLUS Project for Medical Science at Yonsei University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. Kim designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Y. Cho, Y. Lee, J. Lee, S.I. Kim, C.H. Kim, and H.W. Lee performed animal experiments. H. Jeong performed immunohistochemistry experiments. K.T. Nam edited the manuscript and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K.H., Cho, Y., Lee, J. et al. Sexually dimorphic leanness and hypermobility in p16Ink4a/CDKN2A-deficient mice coincides with phenotypic changes in the cerebellum. Sci Rep 9, 11167 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47676-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47676-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.