Abstract

We examined prospective changes in drinking patterns and their associations with socio-behavioral and health status variables in older adults in Spain using data from a prospective cohort of 2,505 individuals (53.3% women) representative of the non-institutionalized population aged >60 years in Spain. Alcohol consumption was assessed at baseline (2008–10) and at follow-up (2012) with a validated diet history. At risk drinking was defined as consuming >14 g of alcohol/day on average or any binge drinking in the last 30 days; lower amounts were considered light drinking. A total of 26.5% of study participants changed their intake during follow-up. Most participants reduced alcohol intake, but 23.3% of men and 8.9% of women went from light to at risk drinking during the study period. Low social connectivity at baseline was linked to at risk drinking for both sexes. However, the observed associations between changes in social connectivity, morbidity, BMI, or dietary habits and changes in drinking patterns differed by sex. We concluded that since about a quarter of older adults in Spain consume more alcohol than recommended, identifying socio-behavioral factors associated with this behavior is key for designing health campaigns targeting excessive alcohol consumption in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol consumption among older adults has been drawing increasing public health interest due to a rapidly growing elderly population and substantial evidence of a causal association between alcohol and disease burden1,2,3 even at substantially lower consumption levels than those previously deemed “safe”4. Due to physiological changes associated with ageing, older adults have a reduced tolerance to alcohol, may suffer ailments potentially aggravated by alcohol, and are likely to take prescriptions that can interact with alcohol. For these reasons, older adults are at increased risk of adverse effects from relatively modest levels of intake5. Although existing evidence points to a downward trend in alcohol consumption as people age6,7, some specifics are varying. Compared to previous cohorts, upcoming groups of older adults include a higher proportion of individuals reporting alcohol consumption over the recommended levels while the usual age-related decline observed has slowed down8. As a result, it is likely that the burden of disease from alcohol intake in older adults will increase in the future3,9,10. In fact, a significant number of older adults are consuming risky levels of alcohol for their age and prescription use11. Among U.S. Medicare recipients aged ≥65 years, 9% report consuming over 30 drinks per month or >3 drinks in one day12. In Spain, 5 to 8% of older adults diagnosed with hypertension, in treatment for diabetes or thrombosis, or taking sedatives report heavy drinking [≥40 g/day of alcohol in men and ≥24 g/day in women)13.

Several studies have assessed changes in alcohol intake over time, and their determinants, in young and middle-age adults [e.g.14,15], but far fewer studies have been conducted in older adults and, specifically, about the influence of social- and individual-level factors on alcohol intake [e.g.7,10,16]. After the age of 60 profound life transitions such as onset of chronic disease, overall functional deterioration, loss of spouse and other family members, retirement, and weakening social and familiar ties are more likely to come about. These transitions and changes in social networks both define the social context of drinking and could influence consumption patterns as alcohol is often used as a stress-buffering mechanism7,17,18,19. A deeper understanding of these issues could guide interventions to prevent excessive alcohol intake in older adults.

Thus, the aim of this paper is threefold. First, we examine how drinking patterns vary in the Spanish older adult population between two time-points in a 3-year period. Secondly, we explore how baseline socio-behavioral and health status variables are prospectively associated with 3-year changes in alcohol consumption. Finally, we identify how changes in these same variables throughout the 3 years are associated with concurrent changes in alcohol intake. Given the gendered social context surrounding alcohol and the unequal distribution of both consumption and of related disease burden by sex2,7,20, these objectives are addressed for men and women separately.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study design is described in detail elsewhere21,22. Briefly, data come from the Seniors-ENRICA cohort, a longitudinal study including 2,614 individuals selected in 2008–10 through stratified cluster random sampling of the non-institutionalized population of Spain aged 60 years and older. First, the sample was stratified by province and size of municipality. Second, clusters were selected randomly in two stages: municipalities and census sections. Finally, the households within each section were selected by random telephone dialling based on the directory of telephone landlines. Subjects within the households were selected proportionally to the sex and age distribution of the Spanish population.

At baseline, we collected comprehensive information on socio-demographic variables, health behaviors, health status indicators and morbidity through computer-assisted telephone interviews and structured questionnaires. Additionally, trained staff conducted two home visits to record a complete diet and alcohol history, to perform a physical examination, and to collect blood and urine samples.

About 3 years later [February through December 2012), 2,519 surviving participants agreed to participate in a follow-up through telephone and at-home interviews for data updates. All study participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital La Paz in Madrid21,22. This research has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards described in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Study variables

Alcohol consumption

Both at baseline and follow-up, participants were administered a validated diet history, based on the one used in the EPIC-cohort study23,24,25. As part of this diet history, we collected detailed information on habitual average alcohol consumption in the preceding 12 months including binge drinking in the last 30 days.

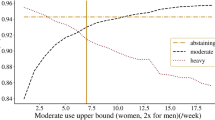

We classified participants of either gender as “at risk drinkers” if they reported consuming more than one U.S. standard drink (>14 g of alcohol) per day on average5,26 or any binge drinking in the last 30 days (≥80 g for men and ≥60 g for women of alcohol in one session)27. Individuals reporting lower consumption, labeled here as light drinkers, correspond to drinkers with the lowest risk of all-cause mortality according to Wood and colleagues4. Non-drinkers included life-long abstainers and very occasional drinkers (i.e., individuals who reported 0 g/day of alcohol intake in the last year but self-described as drinkers). We classified as ex drinkers those individuals who expressed having quit alcohol consumption and reported 0 g/day of alcohol intake in the past 12 months. We differentiated between ex drinkers and non-drinkers because the former may have quit alcohol due to previous health issues (the sick quitter effect) or as a conscious choice for a healthier lifestyle4.

We defined three patterns of drinking change over time for which we had large enough sample sizes: Light drinker at baseline but at risk drinker at follow-up (Light-to-At Risk), light drinker at baseline but ex drinker at follow-up (Light-to-Ex drinker), and at risk drinker at baseline but light drinker at follow-up (At Risk-to-Light). These three categories were compared to those participants who maintained their baseline pattern throughout follow-up. That is, if they were light drinkers at baseline, they also reported light drinking at follow-up and if they were at risk drinkers at baseline, they remained at risk drinkers at follow-up.

Socio-behavioral and health status variables

We included baseline and follow-up variables previously associated with changes in alcohol consumption, including gender, age, educational level, tobacco smoking, marital and employment status, leisure time exercise (expressed in metabolic equivalents-METS), sedentary behavior (time spent watching television or reading per week), obesity, adherence to the Mediterranean diet as per the MEDAS index, physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health-related quality of life based on the SF-12 questionnaire, social support or connectivity (living alone, eating meals alone) [e.g.7,15,19,22,28,29] and the number of physician-diagnoses of the following diseases or conditions: pneumonia, asthma, chronic bronchitis, heart attack, stroke, cardiac failure, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, hip fracture, gallbladder stones, cirrhosis of the liver, urinary tract infection, depression requiring treatment, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, gum disease, and/or cancer. The presence of any of these conditions may have influenced alcohol consumption30 or time spent socializing around alcohol. Participants also reported whether a health care provider had diagnosed them with hypertension, diabetes, and/or high cholesterol levels. We used standard procedures to measure weight and height31 from which we calculated Body Mass Index (BMI) as weight in kg divided by squared height in m.

We calculated change variables using baseline and follow-up values. In the case of continuous variables, we selected cut-points reflecting clinically significant thresholds or the median value at baseline. These values are specified in the corresponding tables.

Statistical analysis

At the bivariate level, we calculated the percentage of participants falling into each of the four consumption patterns at baseline and follow-up. Because aggregate data tend to mask the degree of variation in alcohol consumption over time, we looked at the path participants followed between drinking categories from baseline to follow-up. Given the substantial differences in drinking patterns by gender, all analyses were performed for men and women separately.

At the multivariate level, the dependent variable consisted of each of the two change patterns described above for light drinkers (Light-to-At Risk vs. Continuing Light; Light-to-Ex drinker vs. Continuing Light) plus only one change pattern regarding at risk drinkers (At Risk-to-Light vs. Continuing At Risk) for lack of enough individuals reporting At Risk drinking at baseline and then reporting having quit drinking at follow-up. Thus, we examine a total of three change drinking patterns. In a first model, we summarized the associations of socio-behavioral and health status, and social support variables at baseline with these three changes in drinking patterns using multivariate logistic regression models. These analyses yielded odds ratios (OR) and their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) fully adjusted for the other independent variables of interest in addition to age and baseline alcohol intake. As a next step, we incorporated a set of independent variables capturing changes in socio-behavioral and health variables from baseline to follow-up to the first model. This second model allowed us to estimate relationships between these changes and changes in drinking patterns while controlling for the effect of starting points, i.e., baseline values.

All variables were modeled as categorical using dummy terms, except for the variable capturing the body mass index and the number of morbidities which were kept continuous. Statistical significance was set at two-sided p < 0.05. We used STATA version 11.1 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, 2010) to perform the analyses.

Results

Description of the sample

Of the 2,614 participants from the baseline study, 95 died before the end of follow-up. We also excluded 14 people for lack of data on alcohol consumption, MEDAS, BMI, employment status, or the SF-12. Thus, main analyses were conducted on 2,505 individuals (1,171 men and 1,334 women; 1,546 aged 60–69 years and 959 aged ≥70 years). Almost a quarter had completed secondary level education and one fifth reported university-level degrees. At baseline, 71.5% were married and 18.5% were widowed. Two-thirds were retired (66.3%) and almost 12% were still employed (Table 1).

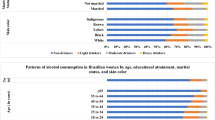

Frequency of main drinking patterns at 2008–10 (T1) and 2012 (T2) by socio-demographic variables

We observed substantial differences in drinking patterns between men and women; for example, women made up a much higher percentage of non-drinkers than men at T1 (83.4 vs. 16.6%), whereas the reverse was true for at risk drinking (21.4 vs. 78.6%). The frequency of light drinkers increased moderately from T1 to T2 whereas the number of non-drinkers decreased to a similar extent. The numbers of ex drinkers and at risk drinkers showed little to no change. The average amount of alcohol consumption increased minimally among light drinkers (0.4 g/day) whereas consumption decreased by 5.5 g/day among at risk drinkers (Table 1).

Individual changes in drinking patterns from T1 to T2

In Tables 2 and 3 we compared drinking patterns reported at T1 (leftmost column) with T2 patterns (top row). Zeros in tables reflect non-viable pattern changes, namely, from any drinking category to non-drinking and from non-drinker to ex drinker. Among men, the ex-drinking and light drinking categories experienced moderate gains (+13.5% and +9.8%, respectively) by drawing from loses in the non-drinking and at risk drinking categories (−22.2% and −5.8%, respectively). In total, 28.6% of men changed the drinking pattern during the 3-year follow-up. Whereas 22.3% (16.7% + 5.6%) of non-drinkers and 28.9% (23.1% + 5.8%) of ex drinkers at T1 reported measurable alcohol consumption (i.e., light or at risk) at T2, 40.5% of all men reported at risk drinking at T2 down from 43.0% at baseline. Among light drinkers at T1, 23.3% became at risk drinkers at T2 (Table 2).

Among women, the group that gained the most individuals during the study period was the ex drinkers (+42.3%), followed by light drinkers (+23.2%). These two categories absorbed those non-drinkers and at risk drinkers who switched patterns (−22.0% and −8.8%, respectively). Overall 24.5% changed drinking patterns over the study’s follow-up. Whereas 22.0% of non-drinkers (20.9% + 1.1%) and 23.1% of ex drinkers (20.2% + 2.9%) at T1 reported measurable alcohol consumption at T2, only 9.4% of all women reported at risk drinking at T2, slightly lower than the 10.3% reported at baseline. Among light drinkers at T1, 8.9% became at risk drinkers at T2 (Table 3).

How are socio-demographic and health-related characteristics at baseline associated with changes in drinking patterns in the following 3 years?

Among male light drinkers at baseline, those living alone were substantially more likely to reach at risk drinking by follow-up than those living with someone (OR 4.72; 95%CI 1.48–14.99). Also, each additional morbidity at baseline was associated with a greater likelihood of quitting alcohol between baseline and follow-up (OR 1.41; 1.01–1.99) (Table 4).

As regards to female light drinkers, those who had all their meals alone more frequently adopted at risk intake at follow-up than those having company at least some times (OR 2.91; 1.17–7.29). Finally, of those presenting at risk drinking at baseline, older women and those spending more time reading were more likely to reduce their intake from at risk to light levels (OR 2.63; 1.05–6.61 and 2.60; 1.08–6.27, respectively) (Table 5).

How are changes in socio-demographic and health-related characteristics between baseline and follow-up associated with changes in drinking patterns during the same period?

Male light drinkers. Among male light drinkers, those who abandoned the Mediterranean diet between baseline and follow-up more than double their likelihood of at risk consumption 3 years later (OR for Light-to-At Risk: 2.29; 1.16–4.50). In contrast, a decrease in time spent reading showed the opposite relationship (OR for Light-to-At Risk: 0.40; 0.17–0.92). Also, each additional morbidity at baseline was inversely associated with at risk consumption (Light-to-At Risk OR: 0.54; 0.35–0.83), and a reduction in number of morbidities during follow-up was linked to more frequent adoption of an at risk pattern (Light-to-At Risk OR: 3.75; 1.60–8.79) independently of how many diagnoses were reported at baseline. However, a decline in the physical component of the SF-12 was positively associated with increased consumption (OR Light-to-At Risk: 1.92; 1.03–3.59) (Table 6).

A reduction in BMI was more likely among those quitting alcohol during follow-up (OR for Light-to-Ex drinker: 9.71; 2.95–31.96) regardless of baseline BMI, which was itself inversely associated with quitting consumption (OR for Light-to-Ex drinker: 0.87; 0.77–0.99). And again, an increase in morbidities during follow-up showed an association with tapering intake during the same time period (OR for Light-to-Ex drinker: 3.25; 1.05–10.05) net of baseline comorbidity, which remained directly associated with quitting drinking (OR for Light-to-Ex drinker: 1.77; 1.04–3.00) (Table 6).

Male at risk drinkers

Men reporting at risk consumption and who reported smoking at baseline were more likely than non- and ex-smokers to continue at risk alcohol consumption rather than switching to light drinking (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 0.42; 0.20–0.87); further, those who quitted tobacco during follow-up were substantially more likely than their counterparts to also quit at risk drinking in favor of light drinking (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 3.20; 1.09–9.38). Baseline BMI was positively associated to improving consumption pattern from at risk to light drinking (OR: 1.08; 1.01–1.15); and, independently of baseline BMI, men who gained weight during follow-up were also more likely to report reducing consumption (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 2.28; 1.01–5.16). Increasing time watching TV during those 3 years was associated to a healthier drinking profile (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 2.00; 1.10–3.65). Lastly, compared to those who did not change their meal habits, individuals who changed from eating in the company of others (at least sometimes) at baseline to always eating alone at follow-up were more likely to reduce their drinking (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 3.03; 1.12–8.20) (Table 6).

Female light drinkers

Among women reporting light drinking at baseline, those who reduced their company during meals to always eating alone at follow-up were more likely to quit drinking (OR for Light-to-Ex drinker: 4.13; 1.34–12.74) (Table 7).

Female at risk drinkers

When examining female at risk drinkers at baseline, those 70 and older and those who abandoned the Mediterranean diet were more likely to have decreased their consumption over the 3-year period (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 4.64; 1.51–14.26 and 4.28; 1.06–17.3, respectively). However, those already retired by baseline were more likely to maintain their at risk consumption (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 0.21; 0.05–0.95) than to reduce it.

Finally, as seen above, women classified at risk drinkers who changed meals habits from eating with others at least sometimes to eating always alone, more frequently reduced alcohol intake (OR for At Risk-to-Light: 13.78; 1.32–144.36). However, the large confidence interval points to small cell sizes and, thus, interpretation should be made with caution (Table 7).

Discussion

In line with previous research supporting increasingly stable alcohol patterns as we age10, our results in older adults from Spain show that over a quarter varied consumption patterns during a 3-year follow-up. In contrast, about 50% of Spanish adults under 60 changed drinking patterns over the same period15. Also as in previous work3,6,7,32, the overall trend denoted a reduction in alcohol intake, except for between one fifth and one fourth of all non-drinkers and 26% of all ex drinkers at baseline who reported measurable alcohol intake 3 years later. This finding is not surprising given the abundant evidence of relapse into alcohol consumption among ex-drinkers, particularly those with a history of problem drinking33.

The overall downward trend in alcohol intake (a reduction of 5.5 g/d in average in 3 years) and the gender and educational differences in consumption are consistent with the country profile recently reported by WHO3, and several studies in older adults7,12,20 but not all34. Also it is worth noting that almost a quarter of older adults at follow-up are still drinking substantial amounts, an average of 2 drinks/day (28.5 g/d). In part, it might simply be the continuation of long-held habits35 and lack of awareness that consumption deemed safe at younger ages may be harmful later in life, especially if taking certain prescriptions. If that were the case, some Spanish elderly may be amenable to change upon receiving correct information12 though reasons for change in consumption levels in older adults vary by age, sex, and social status32. Unfortunately, there is also a great deal of skepticism in this population regarding the harmful effects of alcohol35.

Our results reveal how changes in consumption patterns vary by baseline characteristics and, further, by concurrent changes in those characteristics throughout the 3 years of the follow-up. For both men and women, indicators of low social connectivity at baseline (living/eating alone) were linked to increasing alcohol consumption to potentially harmful levels, as reported by others17,18,19,35,36 and as supported by the notion that social networks rein in negative or unacceptable health behaviors37,38. In contrast, while taking into account loss of spouse/significant other, entering retirement, and changes in perceived mental health-related quality of life, a decrease in social connectivity between baseline and follow-up was accompanied by a reduction in consumption levels. This association challenges the aforementioned studies; however, given we also observed decreased alcohol consumption among men increasing their time watching TV, our findings suggest that substantial reductions in social events (i.e., social connectivity) over a period of time render fewer alcohol consumption opportunities39.

Finally, age-associated changes in drinking patterns varied by sex40 independently of morbidity and both physical and mental components of health-related quality of life. And, as expected, higher morbidity at baseline and subsequent increases in morbid conditions were associated with reductions in alcohol intake, including quitting consumption, in line with previous studies41. Also, the association between reading and healthier drinking patterns in both sexes may reflect higher health literacy levels and/or higher access to health information. The internet has increased the latter greatly; in fact, by 2018 almost half (47%) of Spaniards over 65 had used the internet in the previous 3 months42. Regarding health-related changes, changes in BMI and adherence to a Mediterranean diet were related to changes in alcohol intake patterns43,44 though the direction of these associations varied by drinking pattern. First, BMI at baseline (independently of BMI changes during the follow-up) was directly and significantly associated with a tendency towards light drinking. Thus, as BMI increased, light drinkers at baseline were more likely to stay light drinkers (vs. quitting) and at risk drinkers were more likely to switch to light drinking by the time of follow-up. In turn, changes in BMI during the study period, independently of baseline BMI, showed paradoxical associations with changes in alcohol patterns. We observed a reduction in BMI for light drinkers who quit alcohol but an increase in BMI for at risk drinkers who reduced consumption to light levels. However, these seemingly contradictory findings mirror the overall inconsistency of this field of enquiry45. Previous work shows that the association between alcohol consumption and food intake varies by the individual’s history of alcohol intake. For instance, heavy drinking has been associated with lower energy intake from fat and carbohydrates whereas moderate drinking during meals may increase appetite and caloric consumption45. Overall, our results associating lifestyle and health-status variables with alcohol consumption support previously reported clustering of modifiable health risk factors46.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, these analyses are based on a 3-year follow-up. Whereas follow-up periods under 5 years are not uncommon in this field of inquiry36,38, it may not have been long enough for assessing the real magnitude of variations in drinking patterns. Also, alcohol consumption was self-reported, which allows for both recall error and social desirability bias. Moreover, our category of non-drinkers may have included a small proportion of sporadic drinkers who, at baseline, reported no consumption due to poor memory recall, and who may have slightly increased consumption (or improved recall) at follow-up just enough to cross over to the category of light drinkers. Further, individuals reporting not consuming alcohol may base their response more on self-comparisons with peers or may consider that daily brandy nightcap as self-medicating (e.g., a sleep-aid) rather than drinking, especially among women11. Still, our participants reported not drinking alcohol in very similar proportions as those found in the 2009 European Health Survey in Spain47. In this survey 28.5% of men and 64.7% of women aged 65–74 years reported no alcohol consumption in the previous year. In our study, 19.7% of men and 54.1% of women 60 year-old and older were classified as non-drinkers or ex drinkers in the period 2008–2010. Further, Park, Ryu and Cho30 followed a community-based cohort of 9,001 Korean men and women for 10 years and reported that 76.2% of abstainers at baseline stayed non-drinkers throughout follow-up, which is very similar to our findings (77.8% for men and 78.0% for women after 3 years). The large percentage of women who did not drink in the past year may have reduced our power in the fully adjusted multivariate analyses to detect actual relationships. Finally, although our analyses included measures of physical health, both objective (number of diagnosed conditions) and subjective (perceived physical quality of life) our results are not adjusted for the number of prescription medications.

Major strengths of this study include a longitudinal design of a representative sample of older adults residing in Spain. This Southern Mediterranean country displays drinking patterns and social drinking contexts which are quite different from those in the U.S. or Northern Europe where most published studies are based on. This rich dataset allowed us to examine associations between changes in social connectivity and drinking patterns in the age-group with the highest proportion of widowhood and “empty-nest syndrome.” At a more methodological level, our measure of average alcohol consumption is based on data from a 12-month detailed validated diet history rather than commonly used 30 day-assessments which are less precise capturing current drinkers and heavy drinkers48. Further, our measurement in g/day is an improvement over previous work relying on alcohol data reported in “drinks per day” without specifying the amount of alcohol in one drink [e.g.12] or defining one drink as “a glass of wine…a shot of liquor, or a mixed drink with liquor in it” [e.g.20] which may vary substantially in glass size and amount of alcohol especially if self-served. Finally, by using the NIAAA classification of safe consumption levels specific for healthy older adults not taking prescribed medications5 we were able to identify subtle but clinically significant changes in alcohol intake specific to our population. The use of these lower thresholds rather than those used for younger populations [e.g.14] or the NIAAA-endorsed definition of moderate drinking (≤28 g/day and ≤14 g/day of alcohol for men and women, respectively)49 was recently supported by strong evidence linking modest consumptions to all-cause mortality data4.

In conclusion, whereas prospective research with longer follow-up in this topic is needed, our results indicate that short-term changes in alcohol intake are not infrequent in older ages and that a substantial proportion of older adults are consuming higher amounts of alcohol than recommended. This is especially worrisome given the pervasive underrecognition of alcohol problems50 and the high prevalence of polypharmacy (≥5 prescriptions) in adults aged 65 and older both in Spain (21.9%)51 as well as in Anglosaxon countries like the United States and England (39.0% and 30.9%, respectively)52,53. Ascertaining factors associated with potentially harmful alcohol intake may help health-care providers identify current excessive drinkers or those at risk of becoming one. Finally, these findings may facilitate the development of interventions aimed at minimizing the harmful effects of excessive alcohol intake while maintaining the benefits of socialization, often accompanied by light drinking. Further, strategies should address the various levels of skepticism regarding the harms of alcohol and older people’s susceptibility to “moralizing messaging”54. Interventions should take into account that elderly people are a highly heterogeneous population with different life trajectories, distinctive reasons for drinking or not, diverse alcohol consumption histories, and changing circumstances regarding social connectivity. And that how these factors relate to alcohol consumption vary by gender. Thus, customizing prevention messages as to make them relevant to this group’s diverse concerns, specific needs, and daily routine may serve as a starting point in future prevention strategies.

Data Availability

The data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Breslow, R. A., Castle, I. P., Chen, C. M. & Graubard, B. I. Trends in alcohol consumption among older Americans: National Health Interview Surveys, 1997 to 2014. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 41, 976–986 (2017).

Rehm, J. et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease - An update. Addiction. 112, 968–1001 (2017).

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO, http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/ (2018).

Wood, A. M. et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: Combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet. 391, 1513–1523 (2018).

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Alcohol and your health. Older adults, https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/older-adults (2008).

Brennan, P. L., Schutte, K. K., Moos, B. S. & Moos, R. H. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 72, 308–321 (2011).

Holdsworth, C. et al. Lifecourse transitions, gender and drinking in later life. Ageing Soc. 37, 462–494 (2017).

Anderson, P., Scafato, E. & Galluzzo, L. & VINTAGE project Working Group. Alcohol and older people from a public health perspective. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 48, 232–247 (2012).

World Health Organization. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. Geneva: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66529 (2017).

Sydén, L., Wennberg, P., Forsell, Y. & Romelsjö, A. Stability and change in alcohol habits of different socio-demographic subgroups–a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 14, 525 (2014).

Aira, M., Hartikainen, S. & Sulkava, R. Drinking alcohol for medicinal purposes by people aged over 75: A community-based interview study. Fam Pract. 25, 445–449 (2008).

Merrick, E. L. et al. Unhealthy drinking patterns in older adults: Prevalence and associated characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 56, 214–223 (2008).

León-Muñoz, L. M. et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption in the older population of Spain, 2008–2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 115, 213–24 (2015).

Ilomäki, J. et al. Changes in alcohol consumption and drinking patterns during 11 years of follow-up among ageing men: the FinDrink study. Eur J Public Health. 20, 133–138 (2009).

Soler-Vila, H. et al. Three-year changes in drinking patterns in Spain: A prospective population-based cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 140, 123–129 (2014a).

Perreira, K. M. & Sloan, F. A. Life events and alcohol consumption among mature adults: a longitudinal analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 62, 501–508 (2001).

Das, A. Spousal loss and health in late life: moving beyond emotional trauma. J Aging Health. 25, 221–242 (2013).

Kim, S., Spilman, S. L., Liao, D. H., Sacco, P. & Moore, A. A. Social networks and alcohol use among older adults: A comparison with middle-aged adults. Aging Ment Health. 22, 550–557 (2018).

Watt, R. G. et al. Social relationships and health related behaviors among older US adults. BMC Public Health. 14, 533–543 (2014).

Blazer, D. G. & Wu, L.-T. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Psychiatry. 166, 1162–1169 (2009).

Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. et al. Rationale and methods of the Study on Nutrition and Cardiovascular Risk in Spain (ENRICA). Rev Esp Cardiol. 64, 876–882 (2011).

León-Muñoz, L. M., Guallar-Castillón, P., López-García, E. & Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Mediterranean diet and risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 15, 899–903 (2014).

EPIC Group of Spain. Relative validity and reproducibility of a diet history questionnaire in Spain. I. Foods. EPIC Group of Spain. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 26, Suppl 1, S91–S99 (1997a).

EPIC Group of Spain. Relative validity and reproducibility of a diet history questionnaire in Spain. II. Nutrients. EPIC Group of Spain. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 26, Suppl 1, S100–S109 (1997b).

Guallar-Castillón, P. et al. Validity and reproducibility of a Spanish dietary history. PLoS One. 9, e86074 (2014).

Moore, A. Clinical guidelines for alcohol use disorders in older adults. (American Geriatrics Society, New York, 2003).

Soler-Vila, H. et al. Binge drinking in Spain, 2008-2010. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 38, 810–819 (2014b).

Schröder, H. et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 141, 1140–1145 (2011).

Vilagut, G. et al. Interpretation of SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires in Spain: Physical and mental components. Med Clin. 130, 726–735 (2008).

Park, J. E., Ryu, Y. & Cho, S. I. The Association between health changes and cessation of alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 52, 344–350 (2017).

Gutiérrez-Fisac, J. L. et al. Prevalence of general and abdominal obesity in the adult population of Spain, 2008–2010: the ENRICA study. Obes Rev. 13, 388–392 (2012).

Britton, A. & Bell, S. Reasons Why people change their alcohol consumption in later life: Findings from the Whitehall II Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 10, e0119421 (2015).

Dawson, D. A., Stinson, F. S., Chou, P. & Grant, B. Three-year changes in adult risk drinking behavior in relation to the course of alcohol-use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 69, 866–877 (2008).

Alley, S. J., Duncan, M. J., Schoeppe, S., Rebar, A. L. & Vandelanotte, C. 8-year trends in physical activity, nutrition, TV viewing time, smoking, alcohol and BMI: A comparison of younger and older Queensland adults. PLoS One. 12, e0172510 (2017).

Kelly, S., Olanrewaju, O., Cowan, A., Brayne, C. & Lafortune, L. Alcohol and older people: A systematic review of barriers, facilitators and context of drinking in older people and implications for intervention design. PLoS ONE. 13, e0191189 (2018).

Rezayatmand, R., Pavlova, M. & Groot, W. Socio-economic aspects of health-related behaviors and their dynamics: A case study for the Netherlands. Int J Health Policy Manag. 5, 237–251 (2016).

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R. & Reczek, C. Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annu Rev Sociol. 36, 139–157 (2010).

Umberson, D. & Montez, J. K. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 51(Suppl), S54–S66 (2010).

Moos, R. H., Schutte, K., Brennan, P. & Moos, B. S. Ten-year patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems among older women and men. Addiction. 99, 829–838 (2004).

Molander, R. C., Yonker, J. A. & Krahn, D. D. Age-related changes in drinking patterns from mid-to older age: Results from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 34, 1182–1192 (2010).

Richard, E. L. et al. Alcohol intake and cognitively healthy longevity in community-dwelling adults: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 59, 803–814 (2017).

Abellán García, A. et al. Un perfil de las personas mayores en España, 2019. Indicadores estadísticos básicos. Madrid, Informes Envejecimiento en Red n° 22 (2019). [Profile of older adults in Spain, 2019. Basic statistical indicators. Madrid, Online Reports on Ageing number 22nd, http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/enred-indicadoresbasicos2019.pdf (2019).

Breslow, R. A., Guenther, P. M., Juan, W. & Graubard, B. I. Alcoholic beverage consumption, nutrient intakes, and diet quality in the US adult population, 1999–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 110, 551–562 (2010).

Butler, L., Popkin, B. M. & Poti, J. M. Associations of alcoholic beverage consumption with dietary intake, waist circumference, and body mass index in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2012. J Acad Nutr Diet. 118, 409–420 (2018).

Yeomans, M. R. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav. 100, 82–89 (2010).

Galán, I. et al. Clustering of behavior-related risk factors and its association with subjective health. Gac Sanit. 19, 370–378 (2005).

National Institute of Statistics. European Health Survey in Spain, 2009, http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176784&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195297&idp=1254735573175 (2010).

Midanik, L. T., Ye, Y., Greenfield, T. K. & Kerr, W. Missed and inconsistent classification of current drinkers: Results from the 2005 US National Alcohol Survey. Addiction. 108, 348–355 (2012).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2015–2020, https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix-9/ (2015).

Goldberg, T. H. & Chavin, S. I. Preventive medicine and screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 45, 344–354 (1997).

Carmona-Torres, J. M. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in the older people: 2006–2014. J Clin Nurs. 27, 2942–2952 (2018).

Charlesworth, C. J., Smit, E., Lee, D. S. H., lramadhan, F. & Odden, M. C. Polypharmacy Among Adults Aged 65 Years and Older in the United States: 1988–2010. Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 70, 989–995 (2015).

Dhalwani, N. N. et al. Association between polypharmacy and falls in older adults: A longitudinal study from England. BMJ Open. 7, e016358 (2017).

Kelly, S., Olanrewaju, O., Cowan, A., Brayne, C. & Lafortune, L. Alcohol and older people: A systematic review of barriers, facilitators and context of drinking in older people and implications for intervention design. PLoS One. 13, e0191189 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Plan Nacional sobre Drogas, Ministry of Health of Spain for the support of this work through grant 02/2014. Additional funding was obtained from the FIS grant no. 16/1609 (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, State Secretary of R + D + I and FEDER/FSE). The funding agencies had no role in study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S.V. and F.R.A. conceived and planned the analyses. H.S.V. performed the data analyses with support from R.O. H.S.V. and F.R.A. drafted the paper. R.O., E.G.E. and L.M.L. contributed to the writing of the final manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soler-Vila, H., Ortolá, R., García-Esquinas, E. et al. Changes in Alcohol Consumption and Associated Variables among Older Adults in Spain: A population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 9, 10401 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46591-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46591-0

This article is cited by

-

Association between nutrient intake related to the one-carbon metabolism and colorectal cancer risk: a case–control study in the Basque Country

European Journal of Nutrition (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.