Abstract

Follicular bronchiolitis (FB) is a rare interstitial lung disease (ILD) and has been reported in diverse clinical contexts. Six FB patients demonstrated by surgical lung biopsy (SLB) were reviewed between 2009 and 2017 from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital in China. The average age of subjects was 42 years old (range: 31–55 years). The clinical symptoms were very mild. The laboratory findings showed elevated Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum globulin and anemia. Pulmonary function tests were normal in four cases. Five cases had underlying diseases, such as, Sjo¨gren’s syndrome, multi-centric castlemans’ disease, idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features and abscess. Five cases presented as interstitial lung disease (ILD) on chest imaging with centrilobular or peribronchiolar nodules, ground glass opacities, interlobular septal thickening, cysts and bronchiectasis. Isolated mass was in one patient. The histopathology suggested the changes of FB in all subjects. Prednisone and/or cyclophosphamide were used in four cases, one did the surgery and the other was clinically monitored. All cases were alive at the end of follow up. The adult patients of FB usually have mild symptoms, ILD and underlying diseases. The definite diagnosis needs SLB. The prognosis is depended on their underlying conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Follicular bronchiolitis (FB) is rare bronchiolar disorder characterized by the development of hyperplastic lymphoid follicles with germinal centers around the small airways1. With the enlargement of follicles, the partial bronchial and bronchiolar project into the bronchial lumen. The architecture of the bronchial tree would often be distorted, causing partial bronchial and bronchiolar obstruction. FB is a pathological diagnosis and the precise cause is still unknown. It can be generally classified into primary and secondary form. Secondary FB is usually associated with multiple systemic and pulmonary diseases such as connective tissue disease (CTD) and immunodeficiency, infections, interstitial lung disease (ILD), airway inflammatory diseases2,3. Primary (idiopathic) form of FB is more common in children than in adults4,5. The clinical and radiological features of FB are not specific and relatively little is known about the treatment and survival in adults5. Here is a review of the clinical, laboratory, radiological and pathological findings, treatment and prognosis of six adult patients with FB identified by surgical lung biopsies (SLB) from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital in China.

Subjects and Methods

There were 6076 patients with ILDs admitted to our center between January 2009 and September 2017, and 70 subjects performed surgical lung biopsy (SLB) for diagnosis. Six patients with FB demonstrated by SLB were included in this study. The incidence of FB is about 0.1% in patients with ILD and 8.6% in subjects performed SLB in our single center, respectively. The lung tissue specimens from open lung biopsy (OLB) and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) were reviewed by senior and experienced pathologists. Histological diagnosis of FB required the presence of hyperplastic lymphoid follicles along the distal airways and bronchioles without the evidences of malignant lymphoma6. The data of medical records, laboratory examinations, chest high resolution computed tomography (HRCT), pathology and follow up were analyzed retrospectively. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the ethical committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. Informed consent—for both study participation, and publication of these indirect identifying identifiers and case details in an online open-access publication (when applicable) was attested.

Data availability

The data generated during this present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

There were two male and four female patients in our study. The average age was 42 years (range: 31–55 years old). All patients didn’t have any smoking and dust exposure histories. The clinical complains were very mild and often ignored, including cough (3/6), dyspnea (2/6), intermittent lower fever (1/6), and abnormal opacities on chest X-rays by health screening (3/6). Erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) were increased in all six subjects and serum globulin levels were elevated greatly in 5 cases and 4 patients were presented with mild or moderate anemia and elevated serum C reactive protein (CRP). The findings of pulmonary function tests (PFTs) were normal in four cases, one case with mild decreased forced vital capacity (FVC) pred% and two cases with moderate reduced diffusing capacity carbon monoxide (DLCO) pred%. Underlying systemic and pulmonary diseases were present in five cases, including two patients with Sjogren syndrome (SS) and one developed multi-centric castlemans’ disease (MCD), one with MCD, one with IPAF, and one with abscess, respectively. Only one subjects had no underlying systemic diseases or other possible causes, which may be idiopathic (Shown in Table 1).

Findings of Chest imaging and Histopathology

Chest HRCT showed relatively nonspecific findings including diffuse interstitial changes, such as nodules, ground glass opacities (GGOs) and interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, cysts, lymphadenopathy, and mass. As shown in Table 2, 5 cases (83.3%) with centrilobular or peribronchiolar nodules and GGOs, 4 cases (66.7%) with interlobular septal thickening, 3 cases (50.0%) with bronchiectasis, 3 cases (50.0%) with cysts, 2 cases (33.3%) with “bud-in-tree”, 3 cases (50.0%) with mediastinal and/or hilar lymphadenopathy were present on chest imaging. Only 1 case (17.6%) showed isolated mass. Diffuse ILD was the main pattern on imaging in these patients with FB (5/6, 83.3%) (Table 2 and Figures).

All six patients did SLB, half with OLB and half with VATS. The main pathological manifestation of all subjects was FB, which showed lymphocytic proliferation and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers around the bronchioles, sparing alveolar wall lymphocytic infiltration. Mild peribronchiolar interstitial pneumonitis accompanied with FB were present in 3/6 (50%) cases. One patient was associated with MCD. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), abscess and FB occurred in the same patient with abscess (Table 2 and Figures).

Treatment and Prognosis

Four patients were treated with prednisone, two of them used immunosuppressant (cyclophosphamide or hydroxychloroquine) at the same time. Among the other subjects, the patient with lung mass only had surgery, another had only clinical surveillance, without any special treatment. The duration of follow up was form 15 to 100 months (average time: 54.5 months) after diagnosis. At the end of follow up, all subjects were alive. Three patients were stable. One patient was recurrent after prednisone was discontinued; the other one was only a little worse on chest HRCT, while stable on clinical condition; another one developed MCD and became clinically worse than before (Shown in Table 2).

Case 1

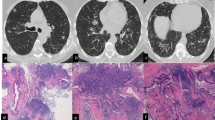

A never-smoking 33-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital because of bilateral multiple nodules on Chest X-ray by healthy screening in May 2009. Chest HRCT showed bilateral centrilobular nodules, cysts, diffuse interlobular septal thickening and GGOs, the nodules were similar to “Tree in bud” in some regions (Fig. 1A,B). PFT was normal. OLB demonstrated FB (Fig. 1C,D). Although the patient had some signs of CTD (serum level of globulin elevated and corneal fluorescent staining positive), it didn’t meet with established classification criteria for a characterisable CTD. It was supposed to be IPAF according the international official statement7. He was initially treated with prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day) and cyclophosphamide (CTX, 400 mg, every 2 weeks), and the dosage of prednisone was tapered gradually. The therapy was continued for 6 months. After six months, the abnormalities on chest CT didn’t have any change compared with before. So prednisone and CTX were stopped. He was free of symptoms and stable on chest imaging during the past 8 years.

Case 1. (A,B) Chest HRCT (May 27, 2009) showed bilateral centrilobular nodules (with partial “bud-in-tree” feature), cysts, diffuse interlobular septum thickening and multiple GGOs in some area. (C,D) Histopathology revealed that FB and peribronchiolar fibrosis, small air way centric lymphoid proliferation with follicular formation and fibrosis reactive germinal center/small mature lymphocytes aggregation (C, HE × 25; D, HE × 200).

Case 2

A 32-year-old woman, non-smoker, presenting with dry cough and dyspnea for 5 years was referred to our medical center in June 2011. Chest HRCT showed centrilobular nodules, patchy consolidation, subpleural cysts and bronchiectasis in both lower lobes (Fig. 2A,B). In local hospital, she had done OLB. The histopathology revealed severe chronic inflammation and lymphocyte hyperplasia. By the consultation of the pathologist in our hospital, the changes of histopathology were consistent with FB. She was diagnosed as FB associated with Primary Sjo¨gren’s syndrome (PSS). Prednisone (40 mg/day), CTX (400 mg, per 2 weeks) and hydroxychloroquine were prescribed to her. The symptoms were improved gradually. Ten months later, the lesions of bilateral lungs were less than before on chest CT scan (Fig. 2C,D). Prednisone was tapered to 5 mg/d and CTX was used only one time every three months. The clinical condition was stable during the past 77 months.

Case 2. (A,B) Chest CT (Jun 23, 2011) showed centrilobular nodules, patchy consolidation and GGOs, subpleural cysts and bronchiolectasis in both lower lobes. (C,D) Chest HRCT (Apr 18, 2012) demonstrated that centrilobular nodules, patchy consolidation and GGOs were all absorbed, and the changes of imaging were better than ten months before.

Case 3

A never-smoker 40-year-old woman complained recurrent fever for 2 years and productive cough and dyspnea for 3 months and was delivered to our center on March 15th, 2012. She was also complained dry mouth during the past few years. PFT showed there was no ventilation impairment, while DLCO was mildly reduced. Chest HRCT revealed nonspecific nodules, interlobular septal thickening, patchy GGOs and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3A–C). We couldn’t get any useful diagnostic information from the pathology of transbronchial lung biopsy which only showed the changes of chronic inflammation. VATS was performed for large samples of lung tissue. The histopathology revealed typical changes of FB and mild peribronchiolar interstitial pneumonitis. We made the final diagnosis as FB associated with PSS. Prednisone (40 mg/d), CTX and hydroxychloroquine were used for this patient. When prednisone was tapered to less than 15 mg/d, the clinical symptoms were recurrent. So, she had used prednisone 20 mg/d for a long time. On May 5th, 2016, chest HRCT showed bilateral multiple nodules and cysts increased, while patchy GGOs decreased compared with before (Fig. 3D,E), The mediastinal lymphadenopathy were larger than before on mediastinal windows (Fig. 3F). In another hospital, she was diagnosed as MCD associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and was treated with chemistry therapy. She planned to do marrow transplantation. The condition was not very well at the end of follow up.

Case 3. (A–C) Chest CT (Mar 16, 2012) showed nonspecific nodules, interlobular septum thickening, diffuse patchy GGOs on lung window and mediastinal lymphadenopath on mediastinal window. (D–F) Chest HRCT (May 5, 2016) revealed increased bilateral multiple nodules and cysts, while decreased patchy GGOs compared with before on lung windows. The mediastinal lymphadenopaths were more and larger than before on mediastinal windows.

Case 4

A 55-year-old woman, never-smoker, was presented with abnormal opacities on chest imaging by healthy screening on June 3, 2013. She didn’t have any symptoms such as fever, cough, sputum or dyspnea. Chest HRCT showed centrilobular nodules, “Tree in bud”, bronchiectasis, patchy GGOs, interlobular septal thickening, mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 4A,B). PFT showed only DLCO pred% was mild decreased. The histopathology of VATS demonstrated FB and interstitial lung disease (Fig. 4C,D). Initially, she was started on prednisone (30 mg/d). The changes on chest HRCT was improved after one year (Fig. 4E,F). Then prednisone was reduced gradually and stopped 2 years later. She had been free of symptoms and didn’t use any medication in the following 2 years. However, the lesions on chest imaging were increased in September 2017, prednisone (30 mg/d) was prescribed to her again.

Case 4. (A,B) Chest HRCT (Jul 3, 2013) showed centrilobular nodules, bronchiolectasis, patchy GGOs, interlobular septum thickening, mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopath. (C,D) The histopathology of VATS demonstrated FB and ILD and small air way centric lymphoid proliferation with follicular formation and reactive germinal center (C, HE × 25; D, HE × 200). (E,F) Chest HRCT scans (Nov 25, 2014) revealed that centrilobular nodules, patchy GGOs and interlobular septum thickening were less than before.

Case 5

A 51-year-old man, non-smoker, was submitted to surgery because of an isolated mass suspected of lung cancer in left upper lobe in March 2016. He had a history of dry cough for more than half a year and expectoration for one month. Chest HRCT showed an isolated mass in the left upper lobe with left hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 5A,B). Bronchoscopy showed the complete obstruction of left upper bronchus. The histopathology of transbronchial lung biopsy demonstrated mucosal chronic inflammation. Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) revealed the consolidation with a little calcium in left upper lung which was regarded as inflammatory mass. He did the lobectomy of left upper lobe. The pathological finding of samples from lobectomy showed FB, lymphocyte interstitial pneumonia (LIP) and abscess. Microscopic appearance showed abscess cavity with chronic inflammatory cells infiltration and fibrosis of cavity wall (Fig. 5C,D). The pathological staining for bacteria, mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungus were all negative. He didn’t have any complaints after the operation for 18 months.

Case 5. (A,B) Chest HRCT (Feb 24, 2016) showed a mass in the left upper lobe with left hilar lymphadenopathy. (C,D) The pathology of samples from lobectomy showed FB, LIP and abscess. Microscopic appearance of abscess cavity with chronic inflammatory cells infiltration and fibrosis of cavity wall (C, HE × 25), peripheral region with FB features (D, HE × 100).

Case 6

A 51-year-old female patient was presented with abnormal opacities on chest-X ray by health screening on May 17, 2016. No wheezes or crackles were heard on bilateral lungs. Laboratory findings revealed anemia with hemoglobin 86 g/l (normal range: 115–150 g/l) and high serum level of globulin with 71.8 g/l (normal range: 20–40 g/l). However, polyclonal immunoglobulin bands were presented in immunofixation electrophoresis and the marrow biopsy demonstrated the changes of neutrophil, blood platelet and hemoglobin were all hyperplastic, without any evidence of malignancy. PFT showed ventilation function was normal and DLCO Pred % was mildly reduced (67.2%). Chest HRCT scan showed that centrilobular and peribronchial nodules, bilateral diffuse thickening of interlobular septum, patchy GGOs, bronchiectasis, and multiple mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 6A,B). The pathology of VATS was consistent with FB and MCD (Fig. 6C,D). Because she didn’t have any complaints, we just monitored her. Although the chest CT scan was a little worse after 6 months, the patient didn’t complain of additional symptoms during the past 15 months.

Case 6. (A,B) Chest HRCT (May 19, 2016) showed that centrilobular and peribronchial nodules, bilateral diffuse thickening of interlobular septum, GGOs, bronchioectasis, multiple mediastinum lymphadenopathy. (C–F) The pathology of VATS was consistent with FB and MCD. The pathology showed lymphoid proliferation with prominent plasma cells infiltration ‘onion-skin’ pattern with CD features in mediastinal lymphonodes (C, HE × 100; D, HE × 400), bronchiocentric lymphoid proliferation, fibrosis with small pulmonary artery adventitial thickening of collegen in lower power (E, HE × 25), ‘onion-skin’ pattern in higher power with CD features (F, HE × 200). The immumohistochemical staining showed both HHV8 and IgG4 were negative (not showed).

Discussion

Follicular bronchiolitis was defined by Bienenstock in 1973, who detailed that stimulation of the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue results in a polyclonal hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles along the bronchioles6. FB is an rare lymphoproliferative lung disease and a histopathological diagnosis by surgical or transbronchial biopsy3. All patients in current study had the definite diagnosis by surgical lung biopsy. Most cases (5/6) had underlying diseases. The incidence of FB is about 0.1% in patients with ILD and 8.6% in subjects performed SLB in our single center, respectively.

The cause of FB is still unclear. Some authors suggested that it may be generated from a hypersensitivity phenomenon to an unknown antigen or related to a protracted infection8. Schmitt et al. proposed that Treg cells restrain autoimmune responses, resulting in an organized and controlled chronic pathological process rather than a progressive disease in a new model of autoimmune FB driven by a steady production of antigen-specific T cells9. Bezrodnik showed that FB may be a phenotype associated CD25 deficiency presenting homozygous missense mutation in the IL-2 receptor (CD25αR) in a female Argentine patient10.

The average age of our six adult patients was 42 years old (range, 31–55 years old). Five cases had underlying diseases and were secondary form, the other one may be idiopathic form. Secondary FB may occur at any age, while the idiopathic form is more commonly seen in pediatric patients5,11,12. Yousem SA et al. indicated that in the setting of CTD, FB occurred mostly in adults, with a mean age of 44 years, while in patients who were immunocompromised, FB tended to occur at a younger age8. FB is just a pathological diagnosis that may be associated with autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency, infections or obstructive airway diseases4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Less frequently it can be idiopathic, especially in adults. Most cases in our study had underlying conditions, only one case was idiopathic. So, FB in adults may be more common in middle age and associated with multiple systemic or pulmonary disorders. It is important to identify the underlying diseases for those with pathological FB due to different treatment modalities and prognosis.

FB patients are usually present with nonspecific signs and symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, fever, hemoptysis, chest pain, weight loss and crackles on auscultation13,20. The clinical symptoms of our six patients were very mild and similar to the published reports, and half cases had no complains. The changes of PFTs were often very mild although the abnormalities on chest imaging were very severe in some cases13,20 ESR is a nonspecific biomarker for acute stages in many diseases, but it was elevated in all six subjects. It may be an interesting phenomenon, but the causes need to be investigated further. Cases with underlying CTDs and MCD could show increased CRP, serum globulin and IgG and anemia, just as our cases15,21,22. However, serum globulin and IgG were decreased greatly in immunodeficiency patients18. Patients with FB usually have mild clinical symptoms and changes in PFTs, the laboratory findings vary greatly depending on the basic clinical settings.

The cardinal imaging features of FB with ILD pattern consist of small centrilobular nodules (1–3 mm), variably peribronchial nodules, and bilateral patchy GGOs1. Howling et al. suggested that nodules were the most common findings in all 12 patients, Ranging from 1–12 mm in size, which were predominantly centrilobular, some were peribronchial1. In our study, patients with ILD had bilateral centrilobular or peribronchial nodules with GGOs. Sometimes nodules can mimic “Tree-in-bud”. Two cases had the classic “Tree in bud”, which may been resulted from the lymphoid follicles becoming densely concentrated in the interstitium adjacent to the bronchioles1,15. Cysts, interlobular septal thickening and bronchiectasis were found in our cases. We speculated that cysts were associated with lymphocytic proliferation just as LIP on chest imaging. Interlobular septal thickening may be due to inflammatory cell infiltration in the interstitium on histology1. Bronchiectasis was a secondary manifestation of FB, which may be due to the compression of bronchiolar lumen by peribronchiolar infiltration. Mediastinal and/or hilar lymphadenopathy on chest imaging were also seen in some of our cases, which could be related to the underlying diseases, such as MCD, PSS and CTD. Infections and small airway diseases are accompanied by the changes of pathological FB2,23,24. The infections of legionella pneumophilia and mycobacterium avium complex could give rise to the development of FB23,25. Ikeri, et al. reported a child FB patient with collapse consolidation of upper left lobe and prominent air bronchograms had left upper lobectomy on account of recurrent cough and progressive shortness of breath, which was very similar to case 6 with the isolated mass of upper left lobe in our study26.

Histological characteristics of FB were hyperplastic lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers distributed along bronchovascular bundles associated with mild degrees of lymphocytic and monocytic cell infiltration in the interlobular septum13. Six subjects in our study were demonstrated FB on histopathology by SLB. The diagnosis of FB required the presence of hyperplastic lymphoid follicles limited to distal cartilaginous airways without histological or immunophenotypic evidence of malignant lymphoma. The main differentiation of FB is with LIP, which shows several histological features that are similar to those seen in FB, and is also seen in patients with CTDs. Distinction between LIP and FB is based mainly on the extent of lymphocytic infiltration, predominantly peribronchial and peribronchiolar in FB but diffuse in LIP1. However, the two conditions can be overlapping just like our one case because they belong to the same spectrum of benign lymphoproliferative lung disease4. A diagnosis of FB can be made when the mononuclear cell infiltration has a predominantly peribronchial and peribronchiolar distribution. This distribution and the focal nature of the infiltrates account for the centrilobular and peribronchial distribution of nodules seen on chest imaging.

Management for FB is usually aimed at the underlying diseases. FB associated with CTDs in adults appeared to partially respond to corticosteroid and immunosuppressant therapy3,13. Iyonaga et al. also showed successful treatment with corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide for 4 year remission in an FB patient related to MCD16. However, Hwangbo et al. described a case of MCD with FB didn’t have any improvement after the therapy of steroid and azathioprine21. Goksel et al. reported FB associated with RA that was controlled successfully by colchicine after she did not respond to systemic steroid therapy2. However, Kinane et al. reported that the response to corticosteroid therapy was minimal in 5 pediatric patients with idiopathich FB5. For those with immunodeficiency, Shipe R et al. suggested that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated FB has been shown to improve with the anti-retroviral therapy17. However, Camarasa EA et al. implied that the lung lesions of FB could progress in spite of proper treatment with immunoglobulins, even though the treatment decreased the frequency and severity of infections18. In our study, four cases were treated with prednisone in combination with CTX or hydroxychloroquine. The responses to steroids and immunosuppressant were similar to published reports3,13, one case progressed, one case was recurrent and another one didn’t response to steroid. Aerni MR reported that one patient was treated with macrolide and then improved, but the role of macrolide therapy for FB need to be explored further13.

The prognosis of FB patients are different between the adults and children. Most of FB patients in adults have underlying diseases and the clinical outcomes are usually associated with the underlying conditions1. Romero S et al. reported that 6 adult patients with FB survived for a mean follow up of 25 months20. Aerni MR. et al. reported 12 FB cases in adults, there was no deaths related to FB or progressive respiratory disease during a median follow-up period of 47 months13. The time of follow up was not very long. Bates CA et al. reported that the younger patients with immunodeficiency may develop a more progressive disease3,27. Idiopathic FB is more common in children. Kinane BT et al. reported 5 pediatric patients with idiopathic FB who were followed up for 2–15 years and the conditions of all subjects improved about 2–4 years of age5. Dias A. et al. reported a child FB with atelectasis was kept asymptomatic for 9 years on daily inhaled corticosteroid after the lobectomy of left upper lung28. FB patients in children reported by Benesch M and Dai YW were all in good conditions for more than 2 years after treatment with steroids or immunosuppressive therapy11,12. Up to the end of follow-up in current study, two cases were stable on clinical conditions and chest imaging; one had recurrence and anther one was worse. Patient with abscess associated FB was stable after operation. The Chest HRCT of the patient with MCD associated FB was a little worse after 15 months, but the clinical condition didn’t deteriorate at all. Therefore, the clinical outcomes of adult patients with FB are up to the underlying conditions and relatively favorable. From all of above, we infer that the prognosis of child FB may be better than adult FB.

Conclusion

Adult FB is associated with several clinical disorders. Patients usually have mild clinical symptoms, elevated ESR and serum globulin, anemia and ILD. The imaging features of FB with ILD are centrilobular or peribronchiolar nodules associated with patchy GGOs. The definite diagnosis needs SBL. Part of patients will respond to corticosteroid therapy. The clinical outcomes of patients with FB in adults depend on their underlying conditions.

References

Howling, S. J., Hansell, D. M., Wells, A. U. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis: thin-section CT and histologic findings. Radiology 212, 637–642 (1999).

Goksel, O., Nart, D., Ergonul, A. G. et al. Successful Colchicine Therapy in a Patient With Follicular Bronchiolitis Presumed to Be Asthma. Respir Care 60, e122–124 (2015).

Tashtoush, B., Okafor, N. C., Ramirez, J. F. et al. Follicular Bronchiolitis: A Literature Review. J Clin Diagn Res 9, Oe01–05 (2015).

Terada, T. Follicular bronchiolitis and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia in a Japanese man. Diagn Pathol 6, 85 (2011).

Kinane, B. T., Mansell, A. L., Zwerdling, R. G. et al. Follicular bronchitis in the pediatric population. Chest 104, 1183–1186 (1993).

Bienenstock, J., Johnston, N. & Perey, D. Y. Bronchial lymphoid tissue. I. Morphologic characteristics. Lab Invest 28, 686–692 (1973).

Fischer, A., Antoniou, K. M., Brown, K. K. et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J 46, 976–87 (2015).

Yousem, S. A., Colby, T. V. & Carrington, C. B. Follicular bronchitis/bronchiolitis. Hum Pathol 16, 700–706 (1985).

Schmitt, E. G., Haribhai, D., Jeschke, J. C. et al. Chronic follicular bronchiolitis requires antigen-specific regulatory T cell control to prevent fatal disease progression. J Immunol 191, 5460–5476 (2013).

Bezrodnik, L., Caldirola, M. S., Seminario, A. G. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis as phenotype associated with CD25 deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol 175, 227–234 (2014).

Dai, Y. W., Lin, L., Tang, H. F. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis in a child. World J Pediatr 7, 176–178 (2011).

Benesch, M., Kurz, H. & Eber, E. et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in two Turkish children with follicular bronchiolitis. Eur J Pediatr 160, 223–226 (2001).

Aerni, M. R., Vassallo, R., Myers, J. L. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis in surgical lung biopsies: clinical implications in 12 patients. Respir Med 102, 307–312 (2008).

Kobayashi, H., Kanoh, S., Motoyoshi, K. et al. Tracheo-broncho-bronchiolar lesions in Sjogren’s syndrome. Respirology 13, 159–161 (2008).

Kinoshita, M., Higashi, T., Tanaka, C. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med 31, 674–677 (1992).

Iyonaga, K., Ichikado, K., Muranaka, H. et al. Multicentric Castleman’s disease manifesting in the lung: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic findings and successful treatment with corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide. Intern Med 42, 182–186 (2003).

Shipe, R., Lawrence, J., Green, J. et al. HIV-associated follicular bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188, 510–511 (2013).

Camarasa Escrig, A., Amat Humaran, B., Sapia, S. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis associated with common variable immunodeficiency. Arch Bronconeumol 49, 166–168 (2013).

Thalanayar, P. M. & Holguin, F. Follicular bronchiolitis in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Australas Med J 7, 294–297 (2014).

Romero, S., Barroso, E., Gil, J. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis: clinical and pathologic findings in six patients. Lung 181, 309–319 (2003).

Hwangbo, Y., Cha, S. I., Lee, Y. H. et al. A Case of Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Presenting with Follicular Bronchiolitis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 74, 23–27 (2013).

Higuchi, T., Nakanishi, T., Takada, K. et al. A case of multicentric Castleman’s disease having lung lesion successfully treated with humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab. J Korean Med Sci 25, 1364–1367 (2010).

Masuda, T., Ishikawa, Y., Akasaka, Y. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis (FBB) associated with Legionella pneumophilia infection. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med 21, 517–24 (2002).

Elliot, J. G., Jensen, C. M., Mutavdzic, S. et al. Aggregations of lymphoid cells in the airways of nonsmokers, smokers, and subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 169, 712–8 (2004).

Wakamatsu, K., Nagata, N., Taguchi, K. et al. A case of follicular bronchiolitis as the histological counterpart to nodular opacities in bronchiectatic mycobacterium avium complex disease. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2012, 214601 (2012).

Ikeri, N. Z., Umerah, G. O., Ugwu, C. E. et al. Follicular Bronchiolitis in a Nigerian Female Child: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Pediatr. 2016, 1096953 (2016).

Bates, C. A., Ellison, M. C., Lynch, D. A. et al. Granulomatous-lymphocytic lung disease shortens survival in common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114, 415–421 (2004).

Dias, Â., Jardim, J., Nunes, T. et al. Follicular bronchiolitis: A rare cause of persistent atelectasis in children. Respir Med Case Rep. 10, 7–9 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Victoria Oluwakemi, Famuyide, D.O. (Grand River Medical group, Dubuque, Iowa, US) for reviewing this manuscript. This work has been partly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670059), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81200049) and Nanjing Medical Science and technique Development Foundation (ORX17005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Lu and Dr Ma collected the data of the patients and wrote the manuscript. Drs Cao, Ma, Zhao and Cai performed the administration of the patents. Dr Meng provided the pictures of the patients and described the changes of histopathology. Dr Wang provided part of the pictures of chest imaging. Dr Cao contributed to the collection and analysis of the data, wrote and reviewed the manuscript and had full access to the vouches for the integrity of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Ma, M., Zhao, Q. et al. The Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Follicular Bronchiolitis in Chinese Adult Patients. Sci Rep 8, 7300 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25670-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25670-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.