Abstract

Specialized electromagnetic fields can be used for nanoparticle manipulation along a specific path, allowing enhanced transport and control over the particle’s motion. In this paper, we investigate the optical forces produced by a curved photonic jet, otherwise known as the “photonic hook”, created using an asymmetric cuboid. In our case, this cuboid is formed by appending a triangular prism to one side of a cube. A gold nanoparticle immersed in the cuboid’s transmitted field moves in a curved trajectory. This result could be used for moving nanoparticles around obstacles; hence we also consider the changes in the photonic hook’s forces when relatively large glass and gold obstacles are introduced at the region where the curved photonic jet is created. We show, that despite the obstacles, perturbing the field distribution, a particle can move around glass obstacles of a certain thickness. For larger glass slabs, the particle will be trapped stably near it. Moreover, we noticed that a partial obstruction of the photonic jet’s field using the gold obstacle results in a complete disruption of the particle’s trajectory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of electromagnetic radiation producing mechanical action on particles has a long history and a wide array of practical applications1. During the 19th century, P. N. Lebedev showed the first experimental demonstration of this phenomena2. Using auxiliary structures such as hyperbolic metamaterials3,4, photonic crystals4,5,6, optical nanofibers and waveguides7,8, localized plasmons9,10 or propagating surface plasmon-polaritons11,12, one can create structured electromagnetic fields for generating optical forces more complex than those in simple optical traps, opening a room of opportunities for enhanced optical transport and flexible control over the motion of particles. These methods of optical manipulation have recently attracted significant attention as they pave the way to the development of complex nano-mechanical devices13 and optically reconfigurable nanostructures14,15.

It is known that dielectric microparticles with refractive index between 1 and 2 allow the creation of a so called “photonic nanojet” (PNJ), a highly-localized, subwavelength, low-divergence beam16. This system could be considered as a perspective auxiliary system for optical manipulation. In particular, PNJs are studied for their capability to go beyond the diffraction limit17, and they can be used for various applications such as biological manipulation18,19, high-resolution microscopy16,17,20, and enhancing inelastic spectroscopy21,22,23. PNJs are primarily generated using symmetric systems such as dielectric spheres, cylinders16,24 and much more rarely – using non-symmetrical particles17,25. It was also previously found that a dielectric corner26 and asymmetric systems can create curved PNJs27.

The structured field of PNJ may induce specific optical forces. In their pioneer work, Cui et al.28 calculated the forces acting on a metallic nanoparticle immersed in a PNJ; among the results they found was the reversion of the optical force for different polarizations of the incident beam. Other previous works on the topic include generating a PNJ from a sphere trapped using double co-propagating optical tweezers29, the forces from a PNJ near subwavelength slits30,31, and another study showing that the standing waves produced by a pair of elongated PNJs is suitable for trapping nanoparticles32. Three-dimensional optical traps using PNJs were also considered33. We emphasize that the previous works regarding PNJ-induced optical forces focused on trapping particles along the axis of symmetry.

In this paper, we present a curved photonic jet, “photonic hook” – a structured field formed by an asymmetric dielectric particle27 – as a method of generating optical forces for moving particles in a curved trajectory. Hence, the photonic hook field combines the features of both PNJs and Airy beams and other self-accelerating beams34. The forces produced by self-accelerating beams were previously studied35,36, however, the generation of accelerating beams is usually achieved using complex, expensive, and demanding techniques37 or through a cylindrical telescopic system38. The presence of bulky optical elements makes regular implementations of self-accelerating beams unsuitable for microfluidic applications and ‘lab-on-a-chip’ platforms. On the contrary to the usual self-accelerating beams, the photonic hook can be created with a compact microscopic optical element, glass cuboid27. Here, we show that this simple asymmetric cuboid works as an auxiliary structure for advanced subwavelength optical micromanipulation, as a method of particle transport along a curved trajectory for potential physical and biological applications. The opto-mechanical effects of structured field that incorporates properties of PNJs and self-accelerating beams were never studied before and in this respect our research is absolutely novel. We consider the behavior of the photonic hook and optical forces in the cases when obstacles of gold or glass with various thicknesses are introduced at the shadow side. We demonstrate that a particle could go around the glass obstacle or be stably trapped near it, which allows new applications in optical tweezing, as well as in making nanomanipulation more flexible.

Forces from Unobstructed Photonic Hook

We consider the cuboid geometry shown in Fig. 1: The cuboid material has refractive index of 1.46 (which corresponds to fused silica in the visible spectral range39), illuminated by a plane wave, wavelength 625 nm, propagating along the x-axis, and polarized along the y-direction, embedded in air. The detailed description of the numerical simulation can be found in the Methods section. The amplitude of electric field E in the z = 0 plane is shown in Fig. 2a. Comparing this photonic jet to the one produced by a cube, shown in Fig. 2b, made of the same material and illuminated with the same wave, we see that the photonic nanojet becomes curved due to the wedge introduced in the system27. We also note that the field produced by the photonic hook has a slightly higher intensity than that of the cube.

An illustration of the system and the produced photonic hook. The hook is shown as an isosurface of the amplitude of the electric field protruding from the cuboid. The grid intersecting the cuboid represents the z = 0 plane. The parameters are taken from27.

Comparison of the field strength E relative to the incident field Ei produced by the (a) asymmetric cuboid and a (b) cube shown in Fig. 1. The directions of the axes shown here are used for all figures throughout the paper. Parameters of the cuboid are shown in Fig. 1; The cube has edges with length of 3λ. Both figures use the same colorbar scale.

When introducing the prism adjacent to the irradiated surface (the input) of the cube, the phase of the transmitted wave in upper and lower parts of the system changes due to the varying thickness of the prism. Accordingly, the electric field strength, illustrated in Fig. 2a, becomes non-symmetric, showing a concave deformation and this forms the curved photonic jet near the shadow surface. Thus, the symmetry breaking allows controlling the shape and the length of the photonic jet: when the triangular prism is added at the irradiated side of the cube, the photonic jet transforms into a pronounced photonic hook. A more detailed consideration of photonic hook phenomenon is described in ref.27. If we introduce the prism adjacent to the shadow surface (the output) of the cube, the photonic hook will not be formed27. Let us now consider the possibility to employ this outstanding property to achieve curved trajectory of the motion of a trapped nanoparticle, which was previously obtained with help of Airy beams only35. One possible application of this study is for optical fractionation40: a mixture of particles with differing refractive indices can be separated using their respective response to the field.

Mathematically, the optical forces acting on an arbitrary object could be obtained by integrating the Maxwell stress tensor41,42 over the surface, surrounding the object. However, this method requires a long computation time: to obtain the full force field, the simulations need to be performed again every time the probe particle is moved around the domain. To simplify the calculation procedure, the forces can be calculated in an approximation of the particle by an electric dipole; this method applies for Rayleigh particles (particle much smaller than the incident wavelength). The formula for the force in electric dipole approximation is41

where x i is the spatial coordinate (i = 1, 2, 3), \({\alpha }={\alpha }{^{\prime} }+i{\alpha }{^{\prime\prime} }\) is the particle’s complex polarizability, and E is the electric field acting on the particle. From this formula, the force can be written as the superposition of gradient and scattering forces41,

The first term of Eq. (2), the gradient force, is proportional to the intensity variation of the electric field; this force is responsible for particle trapping. The second term, the scattering force, arises from the momentum of photons; this non-conservative force acts in the direction of the light propagation (φ is the field phase) and can cause unrestricted particle motion.

First, we investigate the forces produced by the photonic hook without the presence of any obstacles, to figure out if a curved trajectory can be achieved. Here, we compare the results obtained with help of integrating the Maxwell stress tensor on a spherical surface around a gold probe particle, with size 0.03 µm and complex refractive index43 ϵ = −11.208 + 1.3184 i, shown in Fig. 3a, as well as the results, obtained using the dipolar approximation (Eq. (1)), shown in Fig. 3b.

Optical forces obtained for the cuboid using MST integration (a) and the dipolar approximation (b). The color map shows the force magnitude; the streamlines and arrows represent the possible trajectories and force direction correspondingly. The black region at the left represents the location of the cuboid and the white region has the thickness equal to the particle radius. Both figures use the same colorbar scale.

Figure 3a and b show that the resulting forces are nearly identical, since the size of the probe particle used is within the Rayleigh regime. We also compared the forces generated by a Gaussian beam in free space with waist diameter equals to λ; the force generated by the unobstructed photonic hook is about ten times larger in magnitude than that of the Gaussian beam. Additionally, it was previously shown4 that the presence of the Rayleigh probe does not drastically change the field, hence we will use the semi-analytical model (numerically calculated field distributions which are used for analytical calculations of forces) for simplification in later results.

Obstructed Photonic Hook Forces

It is well known that the introduction of a large particle, beyond the Rayleigh regime, in the path of a laser beam can introduce a disturbance in the field due to absorption and scattering. Since we aim to consider the application of photonic hook for guiding particles around obstacles, we then analyze the case of gold and glass slabs placed above the hook’s path (i.e., the obstacle does not completely block the field of the original hook and a nanoparticle is supposed to go around the obstacles). The obstacles have length of 3λ along the z-axis, length of 1.5λ along the y-axis, and the width along the x-axis is varied. In this paper, we chose widths of λ/2 and λ/4, which are 312.5 nm and 156.25 nm, respectively. The obstacles are placed at a length λ/2 away from the cuboid’s right edge, which roughly corresponds to the location of maximum curvature of the hook.

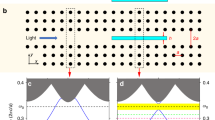

The field perturbation, produced by the glass obstacle above the jet reveals an interesting effect: the trajectory of the particle in the region x > 2500 nm lays above the y-axis for the λ/2 case, and in the λ/4 case, the trajectory nearly coincides with the y-axis, shown in Fig. 4c and d, respectively. The phase difference produced by the field as it goes through the obstacle creates the new jet, shown in Fig. 4a. The gradient force is dominant in this case and is responsible for the trapping seen below the y-axis for the λ/2 case (trapping position is indicated with white circle in Fig. 4c); the influence of the scattering force makes the particle move away from the system in the region x >2 µm. In general, the force is attracting for the probe in the close proximity of the cuboid, but as the probe moves away from the cuboid, the particle is pushed away. Hence, in the case of the glass obstacle, the particle will move around an obstacle with λ/4 thickness, however, for a λ/2-thick glass obstacle, the particle will be trapped.

(a,b) Comparison of the field strength E relative to the incident field Ei produced when the (a) λ/2 glass and (b) λ/2 gold obstacles are introduced. (c–f) Forces produced by the cuboid system with an additional (c,d) glass obstacle with (c) width λ/2 and (d) width λ/4, and a (e,f) gold obstacle with (e) width λ/2 and (f) width λ/4. The color plot represents the force magnitude, the streamlines and arrows represent possible trajectories and the force direction, respectively. The black region at the left represents the cuboid and the white regions have thickness equal to the particle radius. White circles in (c), (e), and (f) show the locations of trapping. Figures (a) and (b); (c) and (d); and (e) and (f) use the same color scales.

In contrast to the previous case shown in Fig. 4c and d, the introduction of the λ/4 gold obstacle to the cuboid system strongly disturbs the photonic hook, making it almost straight as can be seen in Fig. 4b. This is an interesting result because the gold obstacle is out of path of the original jet. This strong disturbance happens because the jet is produced by the wave with varying phase along the cuboid’s shadow side, so the disruption of one part of the wave leads to the disruption of the original jet (in the first case - the glass obstacle is transparent leading to the rather weak disturbance). The forces, shown in Fig. 4e for width of λ/2 and Fig. 4f for λ/4, produced by this system, create two stable trapping locations near the obstacle, as indicated by the white circles. The force pushing the particle away from the system still exists, but it is very small. The field between the cuboid and the obstacle, shown in Fig. 4b, has an appearance similar to the interference pattern of a standing wave; the forces produced by a standing wave nanojet have been previously studied32,44, hence we did not consider this case in our paper.

Conclusion

To conclude, we investigated in detail the optomechanical application of the curved photonic nanojet, photonic hook, produced by an asymmetric cuboid formed by appending a triangular prism to a cube. Using numerical methods, we showed that the trajectory of a probe nanoparticle in the shadow side of the cuboid is curved. Upon the addition of the large glass obstacle to the system, the trajectory shifts towards another path, albeit losing some of its curvature in the long-range; the particle trajectory is seen bending around the glass obstacle for the λ/4 case thickness of the obstacle, whereas a stable trapping point is seen for the λ/2 case. On the other hand, upon the addition of the gold obstacle, the jet is reduced in size; the forces in the long-range are decreased as well. Additionally, stable trapping points are seen around the obstacle for both λ/4 and λ/2 thicknesses.

The revealed new optomechanical effect allows moving particles around a specific path, paving the way to enhanced and more flexible optical manipulation of nanoparticles and their transport along non-straight trajectories without the complicated employment of Airy beams. Moreover, experimental demonstrations of forces from Airy beams35,45 have shown results for manipulating microparticles, whereas we have shown that our method works on the scale of much smaller nanoparticles. The microscopic dimensions and simplicity of our system allows its easy integration into microfluidic devices and ‘lab-on-a-chip’ platforms. For future study, we propose embedding this cuboid on a substrate, representing a more realistic case in which this system can be used in an integrated device. The possibility to bend the particle trajectory around transparent obstacles without changing an optomechanical system opens a room of opportunities for optical, mechanical, biological research and applications, and microfluidics.

Methods

We first simulated the cube-prism structure illustrated in Fig. 1 using Finite Element Method (FEM) software Comsol Multiphysics46. The ratio between the microparticle size and the wavelength of incident light is taken from ref.27 to obtain a pronounced photonic hook. Perfectly matched layers (PML) bound the simulation space at the all sides. At the cube’s/cuboid’s shadow side, additional space with the width 6λ is added to visualize and study the resulting photonic hook and optical forces. We used a free tetrahedral mesh with maximum element size λ/5 for the free-space regions, and λ/5/1.5 for the cuboid. Additionally, we used a free triangular mesh with maximum element size λ/20 for the z-plane to obtain figures of better resolution – the need for very fine meshes in PNJ numerical simulations is a known problem28, and an even finer mesh is required for obtaining the field’s spatial derivatives to obtain the forces.

For the all force maps presented, we introduced a gold sphere with radius 0.03 µm as a probe particle. The incident wavelength is set to 625 nm (f = 480 THz), which corresponds to red visible light. At this frequency, the probe has dielectric permittivity43 ϵ = −11.208 + 1.3184 i. For the simulation used to produce Fig. 3a, the forces were evaluated in a 10 × 10 rectangular grid behind the cuboid (shadow side), and the results were interpolated and plotted using Matlab.

References

Wördemann, M. Structured Light Fields: Applications in Optical Trapping, Manipulation, and Organisation. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Lebedev, P. Untersuchungen über die Druckkräfte des Lichtes. Ann. Phys. 311, 433–458 (1901).

Shalin, A. S., Sukhov, S. V., Bogdanov, A. A., Belov, P. A. & Ginzburg, P. Optical pulling forces in hyperbolic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. A 91 (2015).

Bogdanov, A. A., Shalin, A. S. & Ginzburg, P. Optical forces in nanorod metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 5, 15846 (2015).

Ang, A. S., Sukhov, S. V., Dogariu, A. & Shalin, A. S. Scattering forces within a left-handed photonic crystal. Sci. Rep. 7, 41014 (2017).

Benabid, F., Knight, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Particle levitation and guidance in hollow-core photonic crystal fiber. Opt. Express 10, 1195–1203 (2002).

Xin, H., Cheng, C. & Li, B. Trapping and delivery of Escherichia coli in a microfluidic channel using an optical nanofiber. Nanoscale 5, 6720 (2013).

Shalin, A. S., Ginzburg, P., Belov, P. A., Kivshar, Y. S. & Zayats, A. V. Nano-opto-mechanical effects in plasmonic waveguides. Laser Photonics Rev. 8, 131–136 (2014).

Juan, M. L., Righini, M. & Quidant, R. Plasmon nano-optical tweezers. Nat. Photonics 5, 349–356 (2011).

Shalin, A. S. & Sukhov, S. V. Optical forces in plasmonic nanoantennas. Quantum Electron. 42, 355–360 (2012).

Shalin, A. S. & Sukhov, S. V. Plasmonic nanostructures as accelerators for nanoparticles: Optical nanocannon. Plasmonics 8, 625–629 (2013).

Ivinskaya, A. et al. Plasmon-assisted optical trapping and anti-trapping. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16258 (2016).

Rahneshin, V., Khosravi, F., Ziolkowska, D. A., Jasinski, J. B. & Panchapakesan, B. Chromatic mechanical response in 2-D layered transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDs) based nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 6, srep34831 (2016).

Liu, M., Powell, D. A., Guo, R., Shadrivov, I. V. & Kivshar, Y. S. Polarization-induced chirality in metamaterials via optomechanical interaction. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, n/a-n/a (2017).

Shadrivov, I. V., Kapitanova, P. V., Maslovski, S. I. & Kivshar, Y. S. Metamaterials controlled with light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 083902 (2012).

Chen, Z., Taflove, A. & Backman, V. Photonic nanojet enhancement of backscattering of light by nanoparticles: a potential novel visible-light ultramicroscopy technique. Opt. Express 12, 1214–1220 (2004).

Luk’yanchuk, B. S., Paniagua-Domínguez, R., Minin, I. V., Minin, O. V. & Wang, Z. Refractive index less than two: photonic nanojets yesterday, today and tomorrow [Invited]. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 1820 (2017).

Li, Y.-C. et al. Manipulation and detection of single nanoparticles and biomolecules by a photonic nanojet. Light Sci. Appl. 5, e16176 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Trapping and detection of nanoparticles and cells using a parallel photonic nanojet array. ACS Nano 10, 5800–5808 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Optical virtual imaging at 50 nm lateral resolution with a white-light nanoscope. Nat. Commun. 2, ncomms1211 (2011).

Kasim, J. et al. Near-field Raman imaging using optically trapped dielectric microsphere. Opt. Express 16, 7976–7984 (2008).

Yi, K. J., Wang, H., Lu, Y. F. & Yang, Z. Y. Enhanced Raman scattering by self-assembled silica spherical microparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 063528 (2007).

Lecler, S. et al. Photonic jet driven non-linear optics: example of two-photon fluorescence enhancement by dielectric microspheres. Opt. Express 15, 4935–4942 (2007).

Zhao, L. & Ong, C. K. Direct observation of photonic jets and corresponding backscattering enhancement at microwave frequencies. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 123512 (2009).

Minin, I. V., Minin, O. V. & Geints, Y. E. Localized EM and photonic jets from non-spherical and non-symmetrical dielectric mesoscale objects: Brief review. Ann. Phys. 527, 491–497 (2015).

Kotlyar, V. V., Stafeev, S. S. & Kovalev, A. A. Curved laser microjet in near field. Appl. Opt. 52, 4131 (2013).

Minin, I. V. & Minin, O. V. Diffractive Optics and Nanophotonics. (Springer International Publishing), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24253-8 (2016).

Cui, X., Erni, D. & Hafner, C. Optical forces on metallic nanoparticles induced by a photonic nanojet. Opt. Express 16, 13560–13568 (2008).

Neves, A. A. R. Photonic nanojets in optical tweezers. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 162, 122–132 (2015).

Valdivia-Valero, F. J. & Nieto-Vesperinas, M. Optical forces on cylinders near subwavelength slits: effects of extraordinary transmission and excitation of Mie resonances. Opt. Express 20, 13368–13389 (2012).

Valdivia-Valero, F. J. & Nieto-Vesperinas, M. Optical forces on cylinders near subwavelength slits illuminated by a photonic nanojet. Opt. Commun. 294, 351–360 (2013).

Wang, H., Wu, X. & Shen, D. Trapping and manipulating nanoparticles in photonic nanojets. Opt. Lett. 41, 1652–1655 (2016).

Yannopapas, V. Photonic nanojets as three-dimensional optical atom traps: A theoretical study. Opt. Commun. 285, 2952–2955 (2012).

Mathis, A. et al. Arbitrary nonparaxial accelerating periodic beams and spherical shaping of light. Opt. Lett. 38, 2218–2220 (2013).

Baumgartl, J., Mazilu, M. & Dholakia, K. Optically mediated particle clearing using Airy wavepackets. Nat. Photonics 2, 675–678 (2008).

Schley, R. et al. Loss-proof self-accelerating beams and their use in non-paraxial manipulation of particles’ trajectories. Nat. Commun. 5, ncomms6189 (2014).

Siviloglou, G. A., Broky, J., Dogariu, A. & Christodoulides, D. N. Observation of accelerating Airy beams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 213901 (2007).

Papazoglou, D. G., Suntsov, S., Abdollahpour, D. & Tzortzakis, S. Tunable intense Airy beams and tailored femtosecond laser filaments. Phys. Rev. A 81, 061807 (2010).

Malitson, I. H. Interspecimen comparison of the refractive index of fused silica. JOSA 55, 1205–1209 (1965).

MacDonald, M. P., Spalding, G. C. & Dholakia, K. Microfluidic sorting in an optical lattice. Nature 426, 421–424 (2003).

Novotny, L. & Hecht, B. Principles of Nano-Optics. (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Gao, D. et al. Optical manipulation from the microscale to the nanoscale: fundamentals, advances and prospects. Light Sci. Appl. 6, lsa201739 (2017).

Johnson, P. B. & Christy, R. W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370 (1972).

Minin, I. V., Minin, O. V., Pacheco-Peña, V. & Beruete, M. Subwavelength, standing-wave optical trap based on photonic jets. Quantum Electron. 46, 555–557 (2016).

Zheng, Z., Zhang, B.-F., Chen, H., Ding, J. & Wang, H.-T. Optical trapping with focused Airy beams. Appl. Opt. 50, 43–49 (2011).

COMSOL Multiphysics. Available at: https://www.comsol.com/. (Accessed: 22nd August 2017).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Russian Fund for Basic Research within the project 18-02-00414, the Israeli Ministry of Trade and Labor—Kamin Program, Grant. No. 96717, and partially supported by the Interdisciplinary Engineering-Health Sciences Grant of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. A.S.S acknowledges the support of the President of Russian Federation in the frame of Scholarship SP-4248.2016.1 and the support of Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (GOSZADANIE, Grant No. 3.4982.2017/6.7). I.V.M. was partially supported by Tomsk Polytechnic University within the framework of Tomsk Polytechnic University Competitiveness Enhancement Program and RFBR grant 18-58-80009. The results leading to this manuscript were obtained during the joint PhD program between BGU (under supervision of Alina Karabchevsky) and ITMO (under supervision of Alexander S. Shalin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S.A. performed the numerical simulations and prepared initial draft of the manuscript. A.K. and A.S.S. supervised the project. The paper was written by A.S.A., A.K., I.V.M., O.V.M., S.V.S., and A.S.S. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, A.S., Karabchevsky, A., Minin, I.V. et al. ‘Photonic Hook’ based optomechanical nanoparticle manipulator. Sci Rep 8, 2029 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20224-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20224-4

This article is cited by

-

Optical force on a Rayleigh particle generated by photonic jet

Optical Review (2024)

-

Plasmonic tweezers: for nanoscale optical trapping and beyond

Light: Science & Applications (2021)

-

Twin photonic hooks generated from two adjacent dielectric cylinders

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2020)

-

Optical vacuum cleaner by optomechanical manipulation of nanoparticles using nanostructured mesoscale dielectric cuboid

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Optical hooks

Nature Photonics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.