Abstract

This study aims at evaluating the prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and systemic immune-inflammation indexes (SII) in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients treated with cetuximab. Ninety-five patients receiving cetuximab for mCRC were categorized into the high or low NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII groups based on their median index values. Univariate and multivariate survival analysis were performed to identify the indexes’ correlation with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). In the univariate analysis, ECOG performance status, neutrphil counts, lymphocyte counts, monocyte counts, NLR, PLR, and LDH were associated with survival. Multivariate analysis showed that ECOG performance status of 0 (hazard ratio [HR] 3.608, p < 0.001; HR 5.030, p < 0.001, respectively), high absolute neutrophil counts (HR 2.837, p < 0.001; HR 1.922, p = 0.026, respectively), low lymphocyte counts (HR 0.352, p < 0.001; HR 0.440, p = 0.001, respectively), elevated NLR (HR 3.837, p < 0.001; HR 2.467, p = 0.006) were independent predictors of shorter PFS and OS. In conclusion, pre-treatment inflammatory indexes, especially NLR were potential biomarkers to predict the survival of mCRC patients with cetuximab therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cetuximab, as a functional antagonist of the EGF and TGF ligand, is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), leading to the inhibition of the MAPK pathway and therefore suppresses tumor cell differentiation, proliferation, and angiogenesis to regulates tumor progression1,2,3,4,5. In this way, cetuximab has been reported to improve clinical outcomes for patients with wild-type RAS metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC)6. The Combination of cetuximab with chemotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for mCRC patients, especially patients with left-sided mCRC6,7. Several studies that focused on the MAPK pathway have identified some potential biomarkers with questionable accuracy, but validated predictors of efficacy to cetuximab are still not available8,9,10,11.

It has been suggested that systemic inflammatory response plays an important role in the development and progression of cancer, and that several haematological components take part in forming inflammation-based variables associated with survival in various tumor12,13,14. The inflammatory indexes, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) have been reported to be associated with prognosis in several tumors15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Moreover, previous studies have reported that inflammation indexes were potential markers predicting survival in mCRC patients, such as patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastasis, patients treated with capecitabine combined therapy, and patients treated with bevacizumab25,26,27,28.

This study aimed at investigating inflammatory indexes including NLR, PLR, LMR, and SII for their prognostic significance and ability to predict survival in mCRC patients receiving cetuximab. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the role of pre-treatment inflammatory indexes as predictors for prognosis and treatment efficacy of cetuximab in mCRC patients with wild-type RAS.

Results

Patient population

A total of 7207 patients with CRC were identified from the database and 95 patients were enrolled in this study. The selection process is shown in the Supplementary Fig. 1. Follow-up time ranges from 12 to 72 months, with the median time of 40 months. At the final follow-up date, 74 (77.9%) of 95 patients had experienced progression of disease, 62 (65.3%) died, and 33 patients (34.7%) were alive. Patients divided into groups on the basis of the median value of each marker, were all comparable for age, gender, ECOG performance status, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage and chemotherapy regimen. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. There were 58 males and 37 females with a median age of 56 years (range 27–86). Fifty-five patients (57.9%) had a performance status of 0 while 40 (42.1%) had a performance states of 1. Thirty patients (31.6%) suffered from left colon cancer, 12 (12.6%) surfered from right colon cancer while 53 (55.8%) suffered from rectal cancer. Seventy-one patients (74.7%) with liver metastasis and 24 (25.3%) without, while fourty-three (45.2%) pantients with lung metastases and 52 (54.8%) without. Among those 95 patients, 33 (34.7%), 51 (53.7%) and 11 (11.6%) patients had low, median and high pathological differentiation respectively. Thirty-nine patients (41.0%) were diagnosed at M1a stage while others (59.0%) at M1b. Regarding to the chemotherapy regimen, 26 patients (27.4%) received FOLFOX, and 69 (72.6%) received FOLFIRI (Table 1).

Univariate analysis and Kaplan–Meier curves

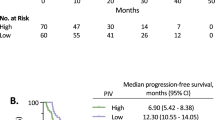

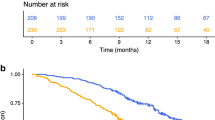

The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.00 months (95% CI 11.67–15.57), and the median overall survival (OS) was 17.00 months (95% CI 17.72–23.04). The results of univariate analysis for the association between each variable (gender, age, performance state, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage and chemotherapy regimen, neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, monocyte counts, platelet counts, NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, lactic dehydrogenase [LDH], carbohydrate antigen 19-9 [CA19-9], and carbohydrate antigen-125 [CA-125]) and PFS or OS are showen in Table 2. In our study, high neutroplil counts, high monocyte counts, high NLR, high PLR and ECOG performance status of 1 were associated with higher risk of disease progression while higher lymphocyte counts was in reverse. As the results suggested that ECOG performance status was the only variable among patient characteristics that significantly affects on survival, patients with performance status of 0 had better median PFS (15.27 vs. 6.40 months, p < 0.001) and OS (25.37 vs. 11.55 months, p < 0.001) than those with performance status of 1. Patients with high neutrophil counts were shown to have significantly worse PFS (14.60 vs. 8.17 months, p < 0.001) and OS (22.97 vs. 13.50 months, p = 0.005), whereas patients with high lymphocyte counts had better PFS (14.07 vs. 6.97 months, p = 0.009) and OS (20.00 vs. 13.40 months, p = 0.037). Patients with high absolute monocyte counts presented shorter median PFS (14.43 vs. 7.92 months, p = 0.018) than patients with low monocyte counts. Patients with high NLR possessed a shorter median PFS (15.90 vs. 6.84 months; p < 0.001) and median OS (24.37 vs. 12.90 months, p = 0.003) compared with those with low NLR. Patients with lower PLR were shown to have a favorable median PFS (13.99 vs. 8.30 months, p = 0.016) compared with those with a higher PLR. Also, patients with high level of LDH were shown to have a poor median PFS (11.60 vs. 9.40 months, p = 0.036). Other factors such as gender, age, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage, chemotherapy regimen, platelet counts, LMR, SII, CA19-9, and CA-125 showed no significant associations with survival (Table 2). Similarly, Kaplan-Meier curves showed that performance status of 1 and high NLR were associated with poor PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p = 0.003), while high PLR was associated with worse PFS (p = 0.016) (Figs 1, 2, 3, Supplementary Figs 2, 3).

Multivariate analysis

The variables that showed association with PFS or OS in univariate analysis were included in the Cox proportional hazard multivariate models. The results of multivariate analysis for the association between each variable (ECOG performance status, neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, monocyte counts, NLR, PLR, and LDH) and PFS or OS are shown in Table 3. The results suggested that neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, NLR and ECOG performance status were independent predictors for both PFS and OS. ECOG performance status of 0 was associated with better median PFS (hazard rate [HR] 3.608, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.096–6.213, p < 0.001) and OS (HR 5.030, 95% CI 2.687–9.417, p < 0.001) than ECOG performance status of 1. High level of neutrophil counts was correlated with unfavorable PFS (HR 2.837, 95% CI 1.664–4.836, p < 0.001) and OS (HR 1.922, 95% CI 1.082–3.414, p = 0.026). High level of absolute lymphocyte counts was correlated with better PFS (HR 0.352, 95% CI 0.210–0.592, p < 0.001) and OS (HR 0.440, 95% CI 0.231–0.692, p = 0.001). Elevated NLR were associated with poor median PFS (HR 3.837, 95% CI 2.117–6.952, p < 0.001) and OS (HR 2.467, 95% CI 1.291–4.717, p = 0.006) (Table 3). In addition, LDH was revealed to be an independent predictive factor of PFS (HR 2.032, 95% CI 1.251–3.300, p = 0.004) but not of OS.

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggested that the inflammatory reaction plays an important role in tumor development29,30,31,32. Accordingly, serum blood cells such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets and monocytes have been assessed in different malignancies and found to be able to predict prognosis and response to treatment33,34,35. Furthermore, several studies have reported that inflammatory indexes including NLR, PLR, LMR and SII were potential prognostic markers for various tumors36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Such parameters were also associated with survival in mCRC patients, including those receiving bevacizumab or palliative chemotherapy25,43. In our study, we observed that pre-treatment inflammatory indexes were potential prognostic factors for survival in mCRC patients receiving cetuximab.

The results of this study suggested that the elevated pre-treatment neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts and NLR were independent predictors for PFS and OS in mCRC patients receiving cetuximab. PLR, LMR and SII showed no significant association with survival. In addition to inflammatory indexes, we analyzed the associations between patients’ clinical factors (gender, age, ECOG performance status, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage, chemotherapy regimen, LDH, CA 19-9, CA-125) and survival. We demonstrated that ECOG performance status was an independent influence factor for both PFS and OS. We also found that patients with low pre-treatment LDH had better PFS but no significant difference in patients’ OS was observed. However, other characteristics such as gender, age, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage and chemotherapy regimen, CA 19-9, and CA-125 showed no significant associations with survival.

Neutrophils promote tumor development through facilitating the secretion of circulating growth factors such asinterlukin-1, interlukin-6 and VEGF while lymphocytes play a significant role in anti-tumor response by promoting cytotoxic cell death and inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and migration14,44,45,46,47. Additionally, neutrophils suppress lymphocytes activities, and therefore suppress the anti-tumor immune response39. Tumor-associated macrophages which are derived from circulating monocytes, promote tumor growth, migration, invasion, and metastasis14,48,49. Thus, neutrophils and monocytes could promote tumor progression, whereas lymphocytes play an important role in the anti-tumor immunity of the host14,47. The role of inflammation in cancer progression is supported by studies which showing that many inflammatory diseases increase the risk of tumors, while aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce the risk14,50,51,52,53. Previous studies suggested that low NLR and high LMR correlated with favorable survival in various cancers, including colorectal cancer, esophagus cancer, gastric cancer and pancreatic cancer16,36,37,38,39,42,54,55,56. The results of this study confirmed that pre-treatment NLR was an independent predictor for PFS and OS. A prognostic factor with RR > 2 is considered useful practical value, which indicated that elevated NLR was a powerful predictive indicator of poor outcome57. This study indicated that LMR was not significantly associated with survival. However, univariable analysis showed a tendency of improved PFS and OS in patients with high LMR which was not an independent prognostic factor. As a result, further studies are expected to confirm the prognostic value of LMR.

Several studies reported that platelets were related to the angiogenesis and tumor invasion through the increasing production of vascular epidermal growth factor in cancer microenvironment58,59. In turn, malignant tumor cells induce platelets aggregation and promote the development of cancer-associated thrombosis60,61. As a result, platelets recruited to the tumor microenvironment consequently allow tumor cells to evade immune surveillance and to be protected from physical clearance61,62. Thus, cancer progression is not only caused by the intrinsic properties of tumor cells but also stimulated by systemic and local inflammatory reactions. In fact, the role of PLR in the prognosis of CRC patients is still controversial. Several studies supported the positive role of pretreatment PLR as a good marker for CRC patients while several studies did not approve this conclusion22,27,28,36,42,48,55,63,64. SII was recently investigated as a prognostic marker in several tumors including esophageal tumor, small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and gastric cancer65,66,67. In the present study, PLR showed significant correlation with PFS but not with OS in univariate analysis. However, no statistically significant correlation was observed about the elevated PLR and poor survival in terms of HR value in the multivariate analysis. Elevated SII indicates high neutrophil counts, high platelet counts and low lymphocyte counts. In this study, we did not confirm the associations of SII with survival. Thus, further studies should be performed to investigate the prognostic value of PLR and SII for the efficacy of cetuximab in mCRC patients.

The limitation of this study lies in its retrospective nature. In addition, our single-center study with a limited number of patients (n = 95) might cause selection bias. Thus, a larger study population, multi-center studies and longer follow-up are needed to validate these results.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that ECOG performance status, neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts and NLR were independent predictors for PFS and OS in mCRC patients, while serum level of LDH was independent predictors for PFS but not for OS. Pre-treatment inflammatory indexes, especially NLR were potential biomarkers to predict the survival of mCRC patients with cetuximab therapy, which would hopefully establish a convenient and inexpensive approach to predict of the efficacy of cetuximab in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patients and inflammatory indexes

We reviewed 7207 colon cancer patients treated at West China hospital between January 2009 and December 2015. Patients who met the following criteria were included: (a) patients with pathological diagnosis of CRC, (b) patients with wild-type RAS mCRC, (c) patients receiving first-line treatment (chemotherapy plus cetuximab), and (d) patients with available and complete basic characteristics, laboratory data and follow-up information. Patients with clinical evidence of acute and chronic inflammation, autoimmune diseases, hematological disorders, or underwent radiotherapy, prior steroid therapy were excluded. The following variables were collected and evaluated in this study: gender, age, ECOG performance status, tumor localization, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, pathological differentiation, M stage and chemotherapy regimen. Laboratory tests results included levels of neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, platelet counts, LDH, CA19-9, and CA-125. All of the data were retrieved from electronic patient record system. Laboratory data were obtained within 10 days prior to the initial administration of cetuximab. Blood cell counting was performed with Sysmex hematology analyzers. Patients were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system. NLR and PLR were defined as the absolute counts of neutrophils and platelets respectively, divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. LMR was calculated by dividing the absolute lymphocyte count by the absolute monocyte count. SII was calculated as platelet count × neutrophil count/lymphocyte count.

All patients were followed every month in the first year, every 3 months in the second year and every 6 months thereafter. The start date of follow-up was the date of patients receiving the first dose of cetuximab, and the end of follow-up was December 2016 or death. This study was approved by the Ethics Administration Office of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. An exemption from informed consent in our study was also approved by this Ethics Administration Office. In addition, all methods in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons on disease-specific variables were performed using Chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables. All p-values were based on two-sided testing, and differences were considered statistically significant when p value is less than 0.05. PFS was defined as the duration from patients primarily receiving cetuximab to the date when radiological evidence of recurrence observed. Patients who died but without progression were not censored to the PFS evaluation. OS was defined as the time interval from patients primary received cetuximab to death from any cause or to the last date of follow-up.

Patients were divided into two groups based on the median index value of NLR (2.34), PLR (142.00), LMR (4.00) and SII (460.66), respectively. NLR ≥2.34, PLR ≥142.00, LMR ≥4.00, and SII ≥460.66 were considered as elevated levels. The cut-off value of neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, monocyte counts and platelet counts were their median value, respectively. In the univariate analysis, the log-rank test (at a significance level of 5%) was used to compare the PFS and OS between two groups. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. All variables with statistic significance in univariate analysis were further evaluated in the multivariate analysis. We investigated the association of multiple variables with survival using the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and their two-sided 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Administration Office of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

References

Pietrantonio, F. et al. First-line anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in panRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 96, 156–166, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.05.016 (2015).

Ciardiello, F. et al. Antiangiogenic and antitumor activity of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor C225 monoclonal antibody in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor antisense oligonucleotide in human GEO colon cancer cells. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 6, 3739–3747 (2000).

Kim, E. S., Khuri, F. R. & Herbst, R. S. Epidermal growth factor receptor biology (IMC-C225). Current opinion in oncology 13, 506–513 (2001).

Polivka, J. et al. New molecularly targeted therapies for glioblastoma multiforme. Anticancer research 32, 2935–2946 (2012).

Voigt, M. et al. Functional dissection of the epidermal growth factor receptor epitopes targeted by panitumumab and cetuximab. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 14, 1023–1031 (2012).

De Roock, W. et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. The Lancet. Oncology 11, 753–762, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70130-3 (2010).

Van Emburgh, B. O. et al. Acquired RAS or EGFR mutations and duration of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. 7, 13665, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13665 (2016).

Bouchahda, M. et al. Early tumour response as a survival predictor in previously- treated patients receiving triplet hepatic artery infusion and intravenous cetuximab for unresectable liver metastases from wild-type KRAS colorectal cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 68, 163–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.011 (2016).

Chen, K. H. et al. Primary tumor site is a useful predictor of cetuximab efficacy in the third-line or salvage treatment of KRAS wild-type (exon 2 non-mutant) metastatic colorectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study. BMC cancer 16, 327, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2358-2 (2016).

Sunakawa, Y. et al. Prognostic Impact of Primary Tumor Location on Clinical Outcomes of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated With Cetuximab Plus Oxaliplatin-Based Chemotherapy: A Subgroup Analysis of the JACCRO CC-05/06 Trials. Clinical colorectal cancer. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2016.09.010 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Potential biomarkers for anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine 37, 11645–11655, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-016-5140-9 (2016).

Kusumanto, Y. H., Dam, W. A., Hospers, G. A., Meijer, C. & Mulder, N. H. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis 6, 283–287, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AGEN.0000029415.62384.ba (2003).

Lu, H., Ouyang, W. & Huang, C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Molecular cancer research: MCR 4, 221–233, https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-05-0261 (2006).

Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Sica, A. & Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07205 (2008).

Asher, V., Lee, J., Innamaa, A. & Bali, A. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio as an independent prognostic marker in ovarian cancer. Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico 13, 499–503, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-011-0687-9 (2011).

Feng, J. F., Huang, Y., Zhao, Q. & Chen, Q. X. Clinical significance of preoperative neutrophil lymphocyte ratio versus platelet lymphocyte ratio in patients with small cell carcinoma of the esophagus. TheScientificWorldJournal 2013, 504365, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/504365 (2013).

Guthrie, G. J. et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 88, 218–230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010 (2013).

Kwon, H. C. et al. Clinical significance of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients with operable colorectal cancer. Biomarkers: biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals 17, 216–222, https://doi.org/10.3109/1354750x.2012.656705 (2012).

Li, M. X. et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of cancer 134, 2403–2413, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28536 (2014).

Malietzis, G. et al. The emerging role of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in determining colorectal cancer treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgical oncology 21, 3938–3946, https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3815-2 (2014).

Smith, R. A. et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. American journal of surgery 197, 466–472, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.057 (2009).

Szkandera, J. et al. The elevated preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio predicts decreased time to recurrence in colon cancer patients. American journal of surgery 208, 210–214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.10.030 (2014).

Wang, D. et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as independent predictors of cervical stromal involvement in surgically treated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. OncoTargets and therapy 6, 211–216, https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s41711 (2013).

Zhou, X. et al. Prognostic value of PLR in various cancers: a meta-analysis. PloS one 9, e101119, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101119 (2014).

Clarke, S. et al. An Australian translational study to evaluate the prognostic role of inflammatory markers in patients with metastatic ColorEctal caNcer Treated with bevacizumab (Avastin) [ASCENT]. BMC cancer 13, 120, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-120 (2013).

Inanc, M. et al. Haematologic parameters in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine combination therapy. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP 15, 253–256 (2014).

Passardi, A. et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictors of prognosis and bevacizumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 7, 33210–33219, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.8901 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios predict chemotherapy outcomes and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastasis. World journal of surgical oncology 14, 289, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-1044-9 (2016).

Alifano, M. et al. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and tumor immune microenvironment determine outcome of resected non-small cell lung cancer. PloS one 9, e106914, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106914 (2014).

Panagopoulos, V. et al. Inflammatory peroxidases promote breast cancer progression in mice via regulation of the tumour microenvironment. International journal of oncology 50, 1191–1200, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2017.3883 (2017).

Park, J. H., Richards, C. H., McMillan, D. C., Horgan, P. G. & Roxburgh, C. S. The relationship between tumour stroma percentage, the tumour microenvironment and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 25, 644–651, https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt593 (2014).

Shrihari, T. G. Dual role of inflammatory mediators in cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 11, 721, https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2017.721 (2017).

Bishara, S. et al. Pre-treatment white blood cell subtypes as prognostic indicators in ovarian cancer. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 138, 71–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.05.012 (2008).

Guillem-Llobat, P., Dovizio, M., Alberti, S., Bruno, A. & Patrignani, P. Platelets, cyclooxygenases, and colon cancer. Seminars in oncology 41, 385–396, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.04.008 (2014).

Kato, T. et al. Clinical significance of urinary white blood cell count and serum C-reactive protein level for detection of non-palpable prostate cancer. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association 13, 915–919, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01440.x (2006).

Azab, B. et al. Pretreatment neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is superior to platelet/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England) 30, 432, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-012-0432-4 (2013).

Feng, J. F., Huang, Y. & Chen, Q. X. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is superior to neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictive factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World journal of surgical oncology 12, 58, https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-58 (2014).

Jiang, N. et al. The role of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients after radical resection for gastric cancer. Biomarkers: biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals 19, 444–451, https://doi.org/10.3109/1354750x.2014.926567 (2014).

Lee, S. et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio in advanced gastric cancer patients treated with FOLFOX chemotherapy. BMC cancer 13, 350, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-350 (2013).

Shin, J. S., Suh, K. W. & Oh, S. Y. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with T1-2N0 colorectal cancer. Journal of surgical oncology 112, 654–657, https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24061 (2015).

Siddiqui, A., Heinzerling, J., Livingston, E. H. & Huerta, S. Predictors of early mortality in veteran patients with pancreatic cancer. American journal of surgery 194, 362–366, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.007 (2007).

Zou, Z. Y. et al. Clinical significance of pre-operative neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors for patients with colorectal cancer. Oncology letters 11, 2241–2248, https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4216 (2016).

Chua, W., Charles, K. A., Baracos, V. E. & Clarke, S. J. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. British journal of cancer 104, 1288–1295, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.100 (2011).

Cools-Lartigue, J. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. The Journal of clinical investigation, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci67484 (2013).

de Visser, K. E., Eichten, A. & Coussens, L. M. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nature reviews. Cancer 6, 24–37, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1782 (2006).

Rossi, L. et al. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio persistent during first-line chemotherapy predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with advanced urothelial cancer. Annals of surgical oncology 22, 1377–1384, https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4097-4 (2015).

Terzic, J., Grivennikov, S., Karin, E. & Karin, M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology 138, 2101–2114.e2105, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058 (2010).

Condeelis, J. & Pollard, J. W. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell 124, 263–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007 (2006).

Evani, S. J., Prabhu, R. G., Gnanaruban, V., Finol, E. A. & Ramasubramanian, A. K. Monocytes mediate metastatic breast tumor cell adhesion to endothelium under flow. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 27, 3017–3029, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.12-224824 (2013).

Baron, J. A. & Sandler, R. S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer prevention. Annual review of medicine 51, 511–523, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.511 (2000).

Daugherty, S. E. et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and bladder cancer: a pooled analysis. American journal of epidemiology 173, 721–730, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq437 (2011).

Garcia-Rodriguez, L. A. & Huerta-Alvarez, C. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer among long-term users of aspirin and nonaspirin nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 12, 88–93 (2001).

Langman, M. J., Cheng, K. K., Gilman, E. A. & Lancashire, R. J. Effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on overall risk of common cancer: case-control study in general practice research database. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 320, (1642–1646 (2000).

Jamieson, N. B. et al. Systemic inflammatory response predicts outcome in patients undergoing resection for ductal adenocarcinoma head of pancreas. British journal of cancer 92, 21–23, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602305 (2005).

Ozawa, T. et al. Impact of a lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in stage IV colorectal cancer. The Journal of surgical research 199, 386–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.014 (2015).

Shibutani, M. et al. Prognostic significance of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. World journal of gastroenterology 21, 9966–9973, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9966 (2015).

Hayes, D. F., Isaacs, C. & Stearns, V. Prognostic factors in breast cancer: current and new predictors of metastasis. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia 6, 375–392 (2001).

Alexandrakis, M. G. et al. Serum proinflammatory cytokines and its relationship to clinical parameters in lung cancer patients with reactive thrombocytosis. Respiratory medicine 96, 553–558 (2002).

Sierko, E. & Wojtukiewicz, M. Z. Platelets and angiogenesis in malignancy. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 30, 95–108, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-822974 (2004).

Goubran, H. A., Stakiw, J., Radosevic, M. & Burnouf, T. Platelets effects on tumor growth. Seminars in oncology 41, 359–369, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.04.006 (2014).

Sharma, D., Brummel-Ziedins, K. E., Bouchard, B. A. & Holmes, C. E. Platelets in tumor progression: a host factor that offers multiple potential targets in the treatment of cancer. Journal of cellular physiology 229, 1005–1015, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24539 (2014).

Jurasz, P., Alonso-Escolano, D. & Radomski, M. W. Platelet–cancer interactions: mechanisms and pharmacology of tumour cell-induced platelet aggregation. British journal of pharmacology 143, 819–826, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0706013 (2004).

Li, Y. et al. Nomograms for predicting prognostic value of inflammatory biomarkers in colorectal cancer patients after radical resection. International journal of cancer 139, 220–231, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30071 (2016).

Ying, H. Q. et al. The prognostic value of preoperative NLR, d-NLR, PLR and LMR for predicting clinical outcome in surgical colorectal cancer patients. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England) 31, 305, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0305-0 (2014).

Feng, J. F., Chen, S. & Yang, X. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is a useful prognostic indicator for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Medicine 96, e5886, https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000005886 (2017).

Hong, X. et al. Systemic Immune-inflammation Index, Based on Platelet Counts and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, Is Useful for Predicting Prognosis in Small Cell Lung Cancer. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine 236, 297–304, https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.236.297 (2015).

Huang, L. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, thymidine phosphorylase and survival of localized gastric cancer patients after curative resection. Oncotarget 7, 44185–44193, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9923 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We greatly thanks to Medbanks(Beijing) Network technology Co. Ltd for patients’ follow-up.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. designed the study, performed the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. X.G. and M.W. performed the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. X.M. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. X.Y. and P.L. participated in the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in the data acquisition and manuscript revising. All authors approved the final manuscript to be submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Guo, X., Wang, M. et al. Pre-treatment inflammatory indexes as predictors of survival and cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with wild-type RAS. Sci Rep 7, 17166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17130-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17130-6

This article is cited by

-

Predictive effect of the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) on the efficacy and prognosis of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer

BMC Surgery (2024)

-

Clinical impact of lymphocyte/C-reactive protein ratio on postoperative outcomes in patients with rectal cancer who underwent curative resection

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-Lymphocyte Ratio in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2022)

-

Preoperative nutrition and exercise intervention in frailty patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Significance of inflammatory indexes in atezolizumab monotherapy outcomes in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer patients

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.