Abstract

For recessive Mendelian disorders, determining the pathogenicity of rare, non-synonymous variants in known causative genes can be challenging without expanded pedigrees and/or functional analysis. In this study, we proposed to establish a database of rare but benign variants in recessive deafness genes by systematic carrier re-sequencing. As a pilot study, 30 heterozygous carriers of pathogenic variants for deafness were identified from unaffected family members of 18 deaf probands. The entire coding regions of the corresponding genes were re-sequenced in those carriers by targeted next-generation sequencing or Sanger sequencing. A total of 32 non-synonymous variants were identified in the normal-hearing carriers in trans with the pathogenic variant and therefore were classified as benign. Among them were five rare (minor allele frequencies less than 0.005) variants that had previously undefined, disputable or even misclassified function: p.A434T (c.1300 G > A) in SLC26A4, p.R266Q (c.797 G > A) in LOXHD1, p.K96Q (c.286 A > C) in MYO15A, p.T123N (c.368 C > A) in GJB2 and p.V1299I (c.797 G > A) in CDH23. Our results suggested that large scale carrier re-sequencing may be warranted to establish a database of rare but benign variants in causative genes in order to reduce false positive genetic diagnosis of recessive Mendelian disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing impairment, resulting from genetic, environmental and other causes, overall occurs in approximately 2–3‰ of children. Among them, an estimated 50–60% of cases can be attributed to genetic causes1. The genetic etiology of deafness is extremely heterogeneous. To date, over 80 genes have been reported to be associated with non-syndromic deafness (The hereditary hearing loss homepage, http://hereditaryhearingloss.org). With recent development and applications of targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), the number of the reported variants for deafness has been drastically increased in just a few years2,3,4,5. On the other hand, it becomes imperative to determine the pathogenicity of the numerous non-synonymous variants identified from the deaf patients. In a recent study, for example, Shearer et al. re-categorized 4.2% of 2197 reported pathogenic variants for deafness as benign based on ethnic-specific differences in minor allele frequencies (MAFs)6. Conventional approaches to determine the pathogenicity of a variant include: (1) repeated documentations of the variant segregating with a disorder in various families; (2) detection of statistically significant differences in the allele frequency between large populations of cases and controls; and (3) extensive genotype–phenotype analyses7,8,9. Those approaches have been critical in providing a comprehensive understanding of correct variant prioritization, phenotypic outcome and clinical prognosis. This task, however, usually takes considerable time and effort to obtain the data. For rare variants with extremely low allele frequencies, it may be impossible to collect enough cases to complete such approaches. The task becomes even more challenging for recessive deafness, which accounts for approximately 80% of the genetic cases, as many such deaf patients do not have family history of deafness, limiting the use of intrafamilial genotype-phenotype co-segregation as an interpretation criterion10. Functional analysis, though convincing in some studies of specific deafness genes and variants, was not generally applicable in comprehensive diagnostic testing due to the large number of variants in question. Other criteria, such as evolutionary conservation analysis of the affected amino acids and computational prediction of the functional effect, provide suggestive rather than conclusive evidence.

Understanding of pathogenic variants is continuously changing in light of newly emerging large-scale population sequencing data. In this study, we proposed a new supporting strategy to identify the rare but benign variants by re-sequencing of the corresponding genes in carriers with known pathogenic variants. For fully penetrant disorders like most cases of recessive genetic deafness, any additional variant identified in the normal-hearing carriers in trans can be classified as benign.

Results

Recruiting of carriers with well-established pathogenic variants in recessive deafness genes

In previous studies, we have identified bi-allelic pathogenic mutations in recessive deafness genes in a number of deaf probands by targeted NGS11. Among these probands, 20 probands were selected who harbored bi-allelic, well-established pathogenic mutations. To qualify for the well-established pathogenic mutations, we chose the variants that were either previously reported with strong genetic evidence (such as linkage analysis, association study or functional study) or truncating variants (nonsense variants, frameshifting indels, etc) in genes in which similar truncating variants have been proven to be pathogenic. First- or second-generation normal-hearing relatives of the probands were then recruited and genotyped for the corresponding variants. From 18 such families, a total of 30 normal-hearing carriers (23 to 38 years old, mean age of 31.3 years) were identified with well-established pathogenic variants. Those pathogenic variants (bold in Supplementary Table S1) included 4 splice site variants, 10 nonsense variants, 8 frameshift variants and 3 missense variants in 11 recessive deafness genes.

Carrier re-sequencing of the corresponding deafness genes

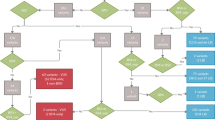

Carrier re-sequencing of the corresponding deafness genes were then performed by Sanger sequencing or targeted NGS in all 30 carriers. The workflow of the data analysis is shown in Fig. 1. Based on family segregation analysis (Fig. 2 and data not shown), a total of 32 non-synonymous variants were identified in trans with the pathogenic variants (Supplementary Table S1). Since the carriers had normal hearing, those variants should be classified as benign.

Family segregation and sequencing of the five rare, nonsynonymous variants. The normal-hearing carriers were marked by the asterisks. Carriers with the rare, non-synonymous variants were pointed by the arrows. The five rare, nonsynonymous variants are presumed benign based on the family segregation data.

Among the 32 non-synonymous variants, 27 variants had MAF higher than 0.005, which rendered them likely benign by the MAF filtering criterion alone as suggested by Shearer et al.6. The remaining five variants, p.A343T in SLC26A4, p.R266Q (c.797 G > A) in LOXHD1, p.V1299I (c.797 G > A) in CDH23, p.K96Q (c.286 A > C) in MYO15A and p.T123N (c.368 C > A) in GJB2, had extremely low MAFs (<0.0007) in the NHLBI and GnomAD databases (Table 1) and changed a highly conserved amino acid (Fig. 3). As shown in Table 1, those five variants were either predicted to be pathogenic by computational tools such as Polyphen2, PROVEAN, SIFT or Mutation Taster, or documented as pathogenic in variant databases such as Deafness Variation Database (DVD), Human Genome Mutation Database (HGMD) or ClinVar. Those previously undefined, disputable or even misclassified function variants were examples whose function can be clarified as benign by the carrier re-sequencing approach.

Clinical re-evaluation of the probands and carriers

For the five families (Fig. 2) with newly-clarified benign variants, we re-evaluated the clinical features of proband 1597-1, 271-1, D1735-1, D1803-1 and D918-1 who harbored known mutations in SLC26A4, LOXHD1, CDH23, MYO15A and GJB2, respectively. Consistent with previous genotype-phenotype correlation studies, all probands had prelingual, profound hearing loss. As expected for patients with pathogenic mutations in SLC26A4, inner ear CT scans showed that Proband D1597-1 with the c.919-2 A > G/c.915insG mutation in SLC26A4 had enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA). As many Chinese Han non-syndromic EVA patients in early childhood, she did not have any thyroid abnormality resembling Pendred Syndrome at age 10 months. The corresponding carriers, D1597-4, D271-4, D1735-3, D1803-3 and D918-3 (Fig. 2), were all over 25 years old at the time of the test. Since most patients with recessive mutations in SLC26A4, LOXHD1, CDH23, MYO15A and GJB2 had congenital or early-onset (<10 years) hearing loss, those carriers were deemed having true normal hearing phenotype. No signs of EVA, such as thyroid abnormality, were observed in carrier D1597-4.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed a simple but effective approach to establish a database of rare but benign variants in recessive deafness genes by carrier re-sequencing. In previous studies, recessive pathogenic mutations have been identified in a large number of deaf patients worldwide. Many normal-hearing family members of those patients may carry a pathogenic variant in a given recessive deafness gene. Under the complete-penetrance mode for most reported recessive genetic deafness cases, any variants identified in trans with the pathogenic variants in the normal-hearing carriers can be classified as benign. In theory, sequencing of the corresponding genes in those carriers will generate a database of benign variants, which would be valuable for reducing the false positive diagnosis during genetic testing and counseling.

In this pilot study, we re-sequenced 30 carriers with well-established pathogenic variants in 11 recessive deafness genes. A total of 32 non-synonymous variants were identified in trans with the pathogenic variants (Supplementary Table S1) and were classified as benign by this carrier re-sequencing approach. Among them, five rare variants with previously undefined, disputable or even misclassified function were best examples to validate this approach (Table 1).

The p.A434T (c.1300 G > A) variant in SLC26A4 was reported as a dominant or de novo pathogenic variant resulting in congenital sensorineural deafness and palmoplantar lichen in a previous study12. This variant was classified as pathogenic in the Deafness Variation Database (DVD) and the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). The LOXHD1 p.R266Q (c.797 G > A) and MYO15A p.K96Q (c.286 A > C) variants were novel. Both were predicted to be pathogenic by computational tools SIFT and Mutation Taster. The functional roles of the GJB2 p.T123N (c.368 C > A) and CDH23 p.V1299I (c.797 G > A) variants were disputable. The p.T123N (c.368 C > A) variant in GJB2 was documented as “pathogenic” in DVD, “deafness?” in HGMD, but “benign/likely benign” in ClinVar. It was predicted as benign by all four computational tools but was reported as pathogenic by several previous studies13, 14. The p.V1299I (c.797 G > A) variant in CDH23 was documented as “likely benign” in both DVD and ClinVar, but was classified as “unclassified variants (UV)” in the original report15, meaning it could not be confidently classified as either pathogenic or neutral based on a grading system recommended by the British Society of Human Genetics. It was predicted as possibly pathogenic by Polyphen2, pathogenic by SIFT and Mutation Taster. Combining the previous reports, variant database documentation, computational prediction and the extremely low MAFs (all less than 0.0007 in the GnomAD and NHLBI databases) of these five variants, our results showed that those functionally undefined, disputable or even misclassified function variants could be demonstrated as benign by the carrier re-sequencing approach. Our pilot study could serve as a blueprint for much larger-scale re-sequencing projects in the next stage and be expanded to other Mendelian genetic disorders.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The deaf probands and the normal-hearing family members were recruited through Ear Institute, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. All subjects signed a written informed consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Auditory evaluation

Auditory evaluation was performed for all subjects including otoscope examination, tympanometry and pure-tone audiometry. The degree of hearing impairment was defined by the average level of hearing loss in the better ear for air pure-tone threshold in speech frequencies at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 kHz. The severity of hearing impairment was calculated as mild (20–40 dB), moderate (41–70 dB), severe (71–95 dB) and profound (>95 dB). Normal hearing was defined as pure-tone thresholds less than 20 dB.

Sequencing

The genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood. Sequencing of GJB2 was completed by Sanger sequencing. Sequencing of all other deafness genes were completed by targeted NGS using the MyGenotics gene enrichment system (MyGenotics, Boston, MA, USA) and the Illumina HiSeq. 2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described16, 17. Data analysis and bioinformatics processing were performed as previously described18. The Reads were aligned to HG19 using the BWA software and the variants were called using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK), both with the default parameters. SNVs and indels were presented using Variant Call Format (VCF) version 4.1 and annotated using the ANNOVAR software. The 144 targeted deafness genes were listed in Supplementary Table S2. Among those 144 genes, only the 86 genes with recognized autosomal recessive inheritance were analyzed, while the remaining 58 genes with dominant and X-linked dominant/recessive inheritance were excluded from the current study.

Computational analysis

MAFs of the variants were obtained from NHLBI (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/, 6503 samples) and GnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/, 123,136 samples) databases. Pathogenicity of the variants were predicted by computational tools PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org), PROVEAN and SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org). Documentation of the pathogenicity of the variants was drawn from Deafness Variation Database (DVD v8.0, http://deafnessvariationdatabase.org/), Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/).

References

Nance, W. E., Lim, B. G. & Dodson, K. M. Importance of congenital cytomegalovirus infections as a cause for pre-lingual hearing loss. J Clin Virol 35, 221–225, doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.017 (2006).

Mutai, H. et al. Diverse spectrum of rare deafness genes underlies early-childhood hearing loss in Japanese patients: a cross-sectional, multi-center next-generation sequencing study. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 8, 172, doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-172 (2013).

Shearer, A. E. et al. Comprehensive genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss using massively parallel sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 21104–21109, doi:10.1073/pnas.1012989107 (2010).

Vona, B. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of deafness genes in hearing-impaired individuals uncovers informative mutations. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 16, 945–953, doi:10.1038/gim.2014.65 (2014).

Yang, T., Wei, X., Chai, Y., Li, L. & Wu, H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 8, 85, doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-85 (2013).

Shearer, A. E. et al. Utilizing ethnic-specific differences in minor allele frequency to recategorize reported pathogenic deafness variants. American journal of human genetics 95, 445–453, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.001 (2014).

Roux, A. F. et al. Molecular epidemiology of DFNB1 deafness in France. BMC medical genetics 5, 5, doi:10.1186/1471-2350-5-5 (2004).

Shi, G. Z. et al. GJB2 gene mutations in newborns with non-syndromic hearing impairment in Northern China. Hearing research 197, 19–23, doi:10.1016/j.heares.2004.06.012 (2004).

Tang, H. Y. et al. DNA sequence analysis of GJB2, encoding connexin 26: observations from a population of hearing impaired cases and variable carrier rates, complex genotypes, and ethnic stratification of alleles among controls. American journal of medical genetics. Part A 140, 2401–2415, doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31525 (2006).

Morton, N. E. Genetic epidemiology of hearing impairment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 630, 16–31 (1991).

Yang, T., Wei, X., Chai, Y., Li, L. & Wu, H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 8, 85, doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-85 (2013).

Ogawa, A. et al. A case of palmoplantar lichen planus in a patient with congenital sensorineural deafness. Clin Exp Dermatol 38, 30–32, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04374.x (2012).

Bonyadi, M. J., Fotouhi, N. & Esmaeili, M. Spectrum and frequency of GJB2 mutations causing deafness in the northwest of Iran. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78, 637–640, doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.01.022 (2014).

Oguchi, T. et al. Clinical features of patients with GJB2 (connexin 26) mutations: severity of hearing loss is correlated with genotypes and protein expression patterns. J Hum Genet 50, 76–83, doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0223-7 (2005).

Le Quesne Stabej, P. et al. Comprehensive sequence analysis of nine Usher syndrome genes in the UK National Collaborative Usher Study. J Med Genet 49, 27–36, doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100468 (2012).

Chai, Y. et al. The homozygous p.V37I variant of GJB2 is associated with diverse hearing phenotypes. Clinical genetics 87, 350–355, doi:10.1111/cge.12387 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing in Uyghur families with non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss. PloS one 10, e0127879, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127879 (2015).

Wei, X. et al. Identification of sequence variants in genetic disease-causing genes using targeted next-generation sequencing. PLoS One 6, e29500, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029500PONE-D-11-19083 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from National Science Foundation of China (81371101 and 81570930 to TY, 81330023 to HW), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission (14DZ1940102 to TY; 14DZ2260300 and 14DJ1400201 to HW), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission – Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant (20152519 to TY), Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine - Gaofeng IV Project (2017GJ004 to TY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: T.Y. and H.W. Performed the experiments: L.H. Analyzed the data: T.Y. and L.H. Collected the samples and reviewed the phenotypes: T.Y., L.H., X.P., P.C. and X.W. Wrote the paper: T.Y. and L.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., Pang, X., Chen, P. et al. Carrier re-sequencing reveals rare but benign variants in recessive deafness genes. Sci Rep 7, 11355 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10099-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10099-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.