Abstract

Various clinical disorders, including psychopathy, and autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, have been linked with impairments in Theory of Mind (ToM). However, although these conditions can co-occur in the same individual, the effect of their inter-play on ToM abilities has not been investigated. Here we assessed ToM abilities in 55 healthy adults while performing a naturalistic ToM task, requiring participants to watch a short film and judge the actors’ mental states. The results reveal for the first time that autistic traits and positive psychotic experiences interact with psychopathic tendencies in opposite directions to predict ToM performance—the interaction of psychopathic tendencies with autism traits was associated with a decrement in performance, whereas the interaction of psychopathic tendencies and positive psychotic experiences was associated with improved performance. These effects were specific to cognitive rather than affective ToM. These results underscore the importance of the simultaneous assessment of these dimensions within clinical settings. Future research in these clinical populations may benefit by taking into account such individual differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Theory of mind (ToM), variably referred to as cognitive empathy and mentalizing, represents a core aspect of human social interaction, allowing one to infer the mental states of others1. Importantly, these abilities can be reliably dissociated into cognitive and affective components2. Cognitive ToM refers to the ability to infer the thoughts, intentions, and beliefs of another, while affective ToM allows one to understand another’s feelings and emotions. Evidence to support this distinction is provided by a series of lesion studies showing that patients with lesions to the ventro-medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) were impaired during tasks that require an understanding of another’s emotional state, despite showing preserved cognitive ToM2,3,4. Further, although a similar network of structures is activated during cognitive and affective ToM, affective ToM also recruits additional regions required for the integration of cognitive and affective information5. Importantly, affective ToM should not be confused with emotional empathy, otherwise termed affective resonance or the ability to feel what another is feeling6. Rather, affective ToM refers to the ability to understand others affective mental states.

Evidence suggests that these two broad components of ToM may be differentially affected by several clinical conditions, including psychopathy7, autism spectrum conditions [ASCs]8, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders [SSDs]9, 10. A dimensional view of psychopathology suggests that subclinical manifestations of these conditions are present in the general population, and can co-occur to varying degrees11,12,13,14. We would note that although the co-occurrence of ASCs and SSDs may appear controversial, recent evidence suggests that these conditions co-occur at an elevated rate, and several models have been proposed to explain their co-occurrence13, 15, 16. Furthermore, subclinical manifestations of these conditions can also explain individual differences in ToM and related abilities11, 17,18,19,20. Importantly, when measured simultaneously in the general population, the precise pattern of ToM impairment observed in relation to these disorders has been found to differ17. However, despite recognition that these conditions can co-occur, the extent to which this co-occurrence can explain individual differences in ToM abilities has remained largely unexplored.

Psychopathy refers to a disorder of personality that is characterized by interpersonal and affective features, including interpersonal charm and a lack of empathy, and lifestyle and antisocial features, including recklessness and impulsivity21. Evidence suggests that psychopaths are impaired at identifying the affective rather than cognitive states of others. For example, psychopaths show difficulty judging others emotions based on facial expression information22, and based on simulated interpersonal interactions23. However, psychopaths may perform at a normal level when asked to judge the affective states of others based on pictures of the eye region24. In addition, while psychopathic traits in a forensic sample are associated with impairments in inferring another’s affective state, these traits are unrelated to inferring another’s cognitive state7. Impairments in affective25, but not cognitive20, ToM have also been found in relation to the broader psychopathy phenotype in the general population.

Autistic individuals also show problems in ToM functioning8. Autism refers to a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by social interaction and communication problems, and the presence of restrictive, repetitive behavioural patterns26. Unlike individuals with psychopathy, individuals with autism show problems in both the cognitive27, 28, and affective domains of ToM29. However, it should be noted that the nature of affective ToM impairments in autism has been debated, and it is argued that these may reflect commonly comorbid alexithymia – a condition associated with difficulties in identifying and describing one’s own emotions30. It has also been shown that the broader phenotype of autism in the general population, but not that of psychopathy, is associated with cognitive ToM impairments20. A similar distinction has also been observed in developmental studies of boys with ASCs or psychopathic tendencies31, and it has been shown that both autistic and psychopathic traits are associated with ToM problems in children with conduct problems32. Taken together, these findings suggest that psychopathy and autism are associated with differing ToM profiles33,34,35.

Since both autism and psychopathy are associated with ToM problems, it has been argued that a ‘double-hit’ of psychopathic and autistic traits would lead to a more pronounced impairment in socio-cognitive abilities32. However, to date, there is a lack of empirical support for this position. In one study of 92 adolescents with ASCs, it was found that although psychopathic tendencies co-occurred at an elevated rate, these tendencies were associated with impaired fear recognition but not impairments in cognitive ToM or cognitive flexibility14. In a separate study of 134 children aged three to nine years, unique negative effects were found for both psychopathic tendencies and autistic symptoms on parent-reported levels of ToM32. However, the outcome measure failed to distinguish between cognitive and affective aspects of ToM. Crucially, neither study found evidence to support the hypothesis of a more pronounced impairment in ToM among those showing co-occurring autism and psychopathic tendencies.

In contrast, nascent evidence suggests that co-occurring psychopathy and schizophrenia may be associated with an attenuating effect on ToM difficulties. Patients with schizophrenia are primarily characterized by psychotic symptoms, including hallucinations and delusions, and also negative symptoms that include diminished emotional expression and avolition26. Although patients with schizophrenia typically show impairments in both the cognitive, and the affective components of ToM10, increasing psychopathic tendencies are associated with better ToM abilities in patients with schizophrenia scoring above the cut-off point for a diagnosis of psychopathy12. Thus, although both psychopathy and schizophrenia are associated with difficulties in ToM, their co-occurrence was not associated with further decline.

Other studies have examined the performance of patients with schizophrenia with and without a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) – a disorder that is commonly comorbid with psychopathy – compared with healthy controls. In one study, it was found that patients with schizophrenia in the absence of ASPD showed reduced affective ToM compared with healthy controls36. In contrast, two groups of violent offenders with ASPD, both with and without schizophrenia, showed a level of performance that was similar to healthy controls36. Thus, the co-occurrence of ASPD and schizophrenia was not associated with a further decline in performance compared with those with schizophrenia alone.

It is argued that measures typically used for the assessment of ToM abilities tap a “narrow” bottom-up view of ToM37, and do not tap more cognitively demanding ToM processing. Furthermore, most paradigms assessing ToM in both clinical and sub-clinical populations do not make the distinction between its cognitive and affective components. To account for these significant gaps, we used the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition [MASC]38, a naturalistic and realistic task that distinguishes between cognitive and affective aspects of ToM. Importantly, this task is sensitive in detecting subtle differences in ToM abilities among healthy adults19, 39.

Given that autism and schizophrenia may affect ToM performance differently when co-occurring with psychopathy, the current study aimed to examine the interaction of psychopathic tendencies with autistic traits, and the expression of positive psychotic experiences, in a non-clinical adult sample while performing the MASC. The assessment of positive psychotic experiences is used in this study based on evidence that negative symptoms do not reliably discriminate between ASCs and SSDs40. Based on evidence for better ToM abilities in patients with schizophrenia and high psychopathic traits12, we predicted that co-occurrence of high psychopathy traits with positive psychotic experiences would be associated with improved cognitive ToM abilities. Although earlier research showed the absence of a ‘double hit’ of co-occurring psychopathy and autism on ToM abilities32, we predicted that the use of a more sensitive task that is both naturalistic, and capable of distinguishing between cognitive and affective ToM, would reveal a further decrement in cognitive ToM among individuals presenting with high traits of both autism and psychopathy. In addition, we predicted that psychopathic tendencies would be associated with increasing errors in affective ToM, while autistic traits and positive psychotic experiences would be associated with errors for both cognitive and affective ToM.

Results

Statistical analysis

We tested for the effects of autism traits (Autism Quotient; AQ), positive psychotic experiences (Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences positive subscale; CAPEp), primary psychopathic tendencies (Levenson Self Report Psychopathy primary subscale; P-LSRP), and all two-way interactions on total ToM errors using ordinary least squares regression models. All regression models were calculated using z standardized predictor values. The rationale for the two-way interactions was motivated by evidence for the co-occurrence of autism and conduct disorders/psychopathic tendencies, on the one hand, and for the co-occurrence of psychosis/schizophrenia and psychopathic tendencies, on the other. While controversial, we also included the interaction of autism and psychosis based on evidence for the co-occurrence of ASCs and SSDs13, 15, 16. We did not include the three-way interaction as, to our knowledge, there is no evidence suggesting that psychopathy, autism and psychotic spectrum disorders simultaneously co-occur. Significant interactions were probed with the Johnson-Neyman method using MODPROBE for SPSS41. This method provides a ‘high-resolution picture’ of the interaction by estimating the value(s) of one predictor, at which the other predictor has a significant effect on the outcome measure. This is established by identifying the precise value(s) along the continuum of one predictor for which the regression slopes of the other predictor are estimated to be significantly different from zero.

Table 1 summarizes the sample scores on the various questionnaires and theory of mind measures.

Total ToM errors

There were no significant relationships of full scale IQ, verbal IQ, performance IQ, age, CESD-R, or S-LSRP with total ToM errors (all r < 0.21 and > −0.12, all p > 0.13). In addition, there were no significant correlations between the different predictor variables: P-LSRP, AQ, and CAPEp (all r < 0.22, all p > 0.12). There was also no difference in the number of overall ToM errors between male and female participants (t = 1.05, df = 53, p = 0.30).

The overall regression model was significant F(6, 48) = 7.54, p < 0.001, ΔR 2 = 0.42). Although parameter estimates showed a significant positive relationship of P-LSRP with total ToM errors (β (SE) = 1.68 (0.47), t = 3.60, p < 0.001), this effect should be interpreted in light of a positive interaction of P-LSRP with AQ scores (β (SE) = 0.97 (0.42), t = 2.30, p = 0.026), and a negative interaction with CAPEp scores (β (SE) = −1.71 (0.45), t = 3.81, p < 0.001). No other main effects or interactions were significant.

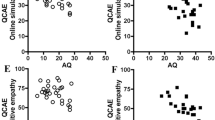

The Johnson-Neyman analysis, presented in Fig. 1a,b, probes the interaction of P-LSRP and AQ. The analysis showed that including the interaction improved the model by 5.65% (F = 5.27, p = 0.026). As shown in Fig. 1a, the relationship of P-LSRP with the number of ToM errors was positive when AQ scores were at and higher than −0.53 SD from the mean (at AQ = −0.53 SD; β (SE) = 1.17 (0.58), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–2.34). Conversely, in Fig. 1b, there was a significant positive relationship of AQ with number of ToM errors when the P-LSRP scores were at and higher than 0.54 SD above the mean (at P-LSRP = .54 SD; β (SE) = 1.00 (0.50), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–2.00) of P-LSRP.

Visualization of the interactive effect of primary psychopathy (P-LSRP) and autism traits (AQ), and of P-LSRP and positive psychotic experiences (CAPEp) on overall theory of mind (ToM) errors. For all panels (a–d), regression lines represent the significant zone (p ≤ 0.05) of the focal predictor at the specified value of the other predictor. Panels 1a and 1b probe the interaction between the P-LSRP and AQ scores. Panel 1a shows that increasing P-LSRP scores significantly increases ToM errors when AQ scores are equal or more than −0.53 SD from the mean. Panel 1b shows that increasing AQ scores significantly increase ToM errors when P-LSRP scores are equal or more than 0.54 SD from the mean. Panels 1c and 1d probe the interaction between the P-LSRP and CAPEp scores. Panel 1c shows that increasing P-LSRP scores significantly increase ToM errors when CAPEp scores are equal or less than 0.39 SD from the mean, but reduce ToM errors when CAPEp scores are more than 2.40 SD from the mean. Panel 1d shows that increasing CAPEp scores significantly increase ToM errors when P-LSRP scores are equal or less than −0.96 SD from the mean, but reduce ToM Errors when P-LSRP scores are equal or more than 0.49 SD from the mean.

Figure 1c,d probes the interaction of P-LSRP and CAPEp. The analysis showed that including the interaction improved the model by 15.54% (F = 14.49, p < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 1c, P-LSRP was associated with an increased number of ToM errors when the CAPEp scores were at and lower than 0.39 SD from the mean (at CAPEp = 0.39 SD; β (SE) = 1.02 (0.51), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–2.04). However, this effect was reversed when the CAPEp scores were at and higher than 2.40 SD from the mean (at CAPE = 2.40 SD; β (SE) = −2.42 (1.20), t = −2.01, p = .05, CI95 = −4.84–0.00). In Fig. 1d, there was a significant positive relationship of CAPEp and number of ToM errors when the P-LSRP scores were at and lower than −0.96 SD from the mean (at P-LSRP = −0.96; β (SE) = 1.31 (0.65), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–2.62). However, this relationship reversed such that there was a significant negative relationship of CAPEp with number of ToM errors when the P-LSRP scores were at and higher than .49 SD from the mean (at P-LSRP = 0.49 SD; β (SE) = −1.17 (0.58), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = −2.34–0.00).

Cognitive and affective ToM errors

Across the full sample, there was no significant difference in the proportion of cognitive and affective errors on the MASC (t = 1.46, p = 0.15). The relationships of full scale, verbal, or performance IQ, age, S-LSRP, or CESD-R with cognitive and affective ToM were non-significant (all r < 0.19 and >−0.17, all p > 0.17). The differences between male and female participants in cognitive (t = 0.97, df = 53, p = 0.34) and affective (t = .86, df = 53, p = 0.39) ToM errors were non-significant.

Proportion of cognitive ToM errors

The overall model for predicting the proportion of cognitive ToM errors was significant F(6, 48) = 7.18, p < 0.001, ΔR 2 = 0.41). Parameter estimates showed that there was a significant relationship of P-LSRP with the proportion of cognitive ToM errors (β (SE) = 0.04 (0.01), t = 2.90, p = 0.006). However, this effect should be interpreted in light of a positive interaction of P-LSRP scores with AQ (β (SE) = 0.03 (0.01), t = 2.26, p = 0.029), and a negative interaction with CAPEp scores (β (SE) = −0.05 (0.01), t = 4.08, p < 0.001) in predicting the proportion of cognitive ToM errors. No other main effects or interactions were significant.

Probing the interaction of P-LSRP with AQ showed that including the interaction improved the model by 5.60% (F = 5.10, p = 0.029). We found a significant positive relationship of P-LSRP scores with the proportion of cognitive ToM errors when the AQ scores were at and higher than −.31 SD from the mean (at AQ = −0.31 SD; β (SE) = 0.028 (0.014), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–0.056). Conversely, the relationship of AQ scores with the proportion of cognitive ToM errors was significantly positive when the P-LSRP scores were at or more than .30 SD from the mean (at P-LSRP = 0.30 SD; β (SE) = 0.025 (0.012), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–0.05).

Probing the interaction of P-LSRP with CAPEp showed that including the interaction improved the model by 18.3% (F = 16.67, p < 0.001). We found a significant positive relationship of P-LSRP scores with the proportion of cognitive ToM errors when the CAPEp scores were at and lower than .21 SD from the mean (at CAPEp = 0.21 SD; β (SE) = 0.026 (0.013), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = 0.00–0.051). However, this effect was reversed such that there was a significant negative relationship of P-LSRP with the proportion of cognitive errors when CAPEp scores were at and higher than 1.79 SD from the mean (at CAPE = 1.79 SD; β (SE) = −0.051 (0.025), t = −2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = −.10–0.00). Conversely, there was a positive relationship of CAPEp and cognitive ToM errors when the P-LSRP scores were at and lower than −1.15 SD from the mean (at P-LSRP = −1.15; β (SE) = 0.038 (0.019), t = 2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = .00–0.075). However, this relationship reversed such that the association between CAPEp and proportion of cognitive ToM errors was negative when the P-LSRP scores were at and higher than .21 SD from the mean (at P-LSRP = 0.21 SD; β (SE) = −0.029 (0.014), t = −2.01, p = 0.05, CI95 = −0.057–0.00).

Proportion of affective ToM errors

The overall model for predicting the proportion of affective ToM errors was significant F(6, 48) = 2.42, p = 0.04, ΔR 2 = 0.14). Parameter estimates suggested that the proportion of affective errors significantly increased with increasing P-LSRP scores (β (SE) = 0.04 (0.02), t = 2.56, p = 0.014). No other main effects or interactions were significant.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the interplay between psychopathic tendencies, autism traits, and positive psychotic experiences in predicting performance on the MASC, a naturalistic and realistic test of ToM abilities. We found that primary psychopathic traits were associated with ToM task performance, but that these relationships depended on levels of both autism traits and positive psychotic experiences. In particular, we found that the interaction of psychopathic tendencies and autism traits was associated with a decrement in ToM performance, whereas the interaction of psychopathic tendencies with positive psychotic experiences was associated with improved ToM performance.

Consistent with our hypothesis, there was a significant interaction of primary psychopathic tendencies with autism traits such that high scores on both measures were associated with a greater overall number of ToM errors. This finding is in contrast to those of an earlier study that failed to find an interaction of psychopathic and autistic traits in a developmental sample32. The results reported here are therefore the first to show support for the expected deleterious effects of this ‘double-hit’ of psychopathic tendencies and autism traits on ToM abilities. Conversely, the interaction of primary psychopathic tendencies with positive psychotic experiences showed that increasing scores on both scales was associated with significantly improved overall ToM performance. Notably, these results are consistent with findings suggesting that extreme levels of psychopathic tendencies among patients with schizophrenia was associated with better ToM abilities, compared with patients with lower psychopathic tendencies12. The results reported here are the first to show evidence for a similar effect in relation to the broader phenotype of these disorders in a non-clinical sample.

When considering the proportion of cognitive and affective ToM errors, it transpires that the interactions we observed for overall ToM errors were specific to cognitive ToM errors. As for the overall ToM errors, the effect of psychopathic tendencies on cognitive ToM errors depended on the relative expression of autism and psychosis traits such that, on the one hand, increasing psychopathic and autistic traits were associated with increased cognitive ToM errors, and on the other hand, increasing psychopathic and psychosis traits were associated with reduced cognitive ToM errors. Affective ToM errors were uniquely and positively associated with psychopathic tendencies.

In an attempt to shed light on the mechanism underlying this pattern of results, we make two main observations. First, autism traits and positive psychotic experiences interacted with psychopathic tendencies in opposite directions. This pattern of results is consistent with the diametric model42, which posits that ASCs and SSDs have opposing effects on ToM abilities, whereby ASCs are associated with reduced ToM and SSDs with hyper-ToM, a tendency to over-attribute/-generate mental states about others43. It has been shown that psychopathy and autism are associated with distinct neurocognitive underpinnings33, 35, 44, and that the features associated with these conditions may not overlap32. Thus, the combined worsening effect of autistic traits and psychopathic tendencies on ToM performance is conceivable in light of robust evidence associating autism, and its broader phenotype, with impaired cognitive ToM20, 31, 34.

The mechanism underlying better cognitive ToM abilities in individuals scoring high on both psychopathic tendencies and positive psychotic experiences is less clear. However, we speculate that if positive psychotic experiences are associated with a greater ability to generate hypotheses about the mental states of others42, 43, then this might be advantageous for individuals with co-occurring high psychopathic tendencies. Imaging studies have shown that individuals with clinically elevated levels of psychopathy or ASPD show a greater reliance on cognitive processes, thought to represent a compensatory mechanism in the absence of affective processing36, 45, 46. Thus, when combined with a greater number of alternative mental state attributions, it is possible that this cognitive route may prove beneficial for individuals with co-occurring high psychopathic tendencies and psychosis traits. Consistent with this hypothesis, there is evidence to suggest that the co-occurrence of psychopathic tendencies in SSDs may be associated with an increased propensity for interpersonal charm, cunning, and instrumental aggression12.

Second, we observe that while psychopathic tendencies had a unique and negative effect on affective ToM errors, its effect on cognitive ToM errors was moderated by the relative expression of autistic traits and psychotic experiences. It has been argued that situations that involve affective ToM entail more self-reflection, and require the integration of affective and cognitive information, compared with situations involving cognitive ToM6. Psychopathic tendencies are associated with reduced affective resonance to others emotional expressions, and reduced activation of regions including the amygdala and anterior insula that are involved in emotion and empathy47. Hypoactivation of these regions has also been observed in relation to psychopathic tendencies during affective ToM task performance, and may reflect a failure to process emotionally salient cues, including facial expressions and body postures48. In contrast, autistic traits, as pointed above, are related to impairments in cognitive ToM, but not in affective resonance or emotional empathy, that is, the ability to feel what another is feeling31, 33, 44. Indeed, individuals with autism may resonate with the emotional experience of others to a normal, or even heightened, degree49, 50. This distinction between psychopathic tendencies and autism traits likely accounts for the absence of a psychopathy-autism interaction in predicting affective ToM.

Taken together, our findings may have implications for understanding the aggressive behaviours associated with psychopathic tendencies. For example, better ToM abilities may be associated with a more cunning and deceitful interpersonal style in psychopathy, and a greater incidence of premeditated or goal directed aggression12, 51, 52. Thus, it may be predicted that the aggressive behaviours of those with elevated psychopathic tendencies and high levels of positive psychotic experiences would be more instrumental compared with those who score relatively more highly on one measure compared with the other. In contrast, adolescents with ASCs and elevated psychopathic traits do not appear to show elevated rates of conduct problems14. This finding is interesting and suggests that psychopathy related impairments that are not seen in autism, including in resonating with others emotions and understanding others affective states, may account for increased rates of aggression in relation to psychopathic, but not autistic traits33, 44.

Our results need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. The sample recruited in this study was relatively small with the majority being female college students. While we observed no effect of participant sex on ToM task performance in the current study, the extent to which there may be sex differences in the relationships should be investigated further, given previous reports highlighting differential relationships among boys and girls in the relationship of psychopathic traits with empathic abilities53. Furthermore, despite recent findings on the relationship of psychopathic tendencies with ToM in patients with schizophrenia12, these results are yet to be mirrored in clinical patient samples with extreme levels of autism.

Our study is the first to show that autistic traits and positive psychotic experiences interact with psychopathic tendencies in opposite directions to predict ToM performance. This modulation is specific to cognitive rather than affective errors. We are aware of the debate regarding the relevance of effects associated with attenuated clinical expressions in the healthy population to clinical entities. However, these results underscore the importance of the simultaneous assessments of these dimensions within clinical settings, particularly given the increased recognition of the co-occurrence of these conditions, and the dimensional view of psychopathology. Perhaps the inconsistencies in the literature with regard to the relationship between psychopathic tendencies and ToM abilities reflect individual differences in the expression of autism and psychosis. Future research concerned with socio-cognitive abilities in these clinical populations may benefit by taking into account such individual differences.

Method

Participants

A sample of 55 healthy adults (16 males, 39 females), aged between 18 and 37 (M (SD) = 20.00 ± 2.59) were recruited from the student population at the University of Birmingham, UK, and participated in return for course credit. Participants reported no history of psychiatric illness, epilepsy, neurological disorders, brain injury or alcohol or substance abuse problems. Written informed consent was received from each participant after the nature of the study had been explained. All experiments were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by the University of Birmingham Research Ethics Committee.

Materials

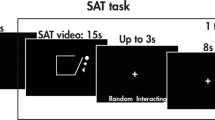

The Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition (MASC)

The MASC38 is a 15-minute video film depicting several scenarios revolving around four friends making arrangements to meet for dinner, preparing and eating a meal, and playing a game. The scenarios are played out in different locations between two, three, or all four of the characters, both in person and over the phone. Across these different social situations the characters show misunderstandings, express irony and ambiguous body language, act flirtatiously, and make insulting comments. The task consists of 51 multiple-choice questions of which six were control questions. The critical 45 questions aimed to test the participants’ abilities to infer the thoughts, intentions, feelings, and emotions of the characters. Each question was presented following a short clip from the movie. The total number of correct responses reflects an individual’s general ToM performance. In addition, the MASC can distinguish between cognitive and affective ToM on the basis of questions that ask about knowledge, beliefs and intentions (28 questions), versus feelings and emotions (17 questions). An example cognitive question asks, “What does Michael think Cliff is laughing about?” An example affective question asks, “What is Sandra feeling?”

Levenson Self Report Psychopathy scale (LSRP)

The LSRP54 assesses psychopathic traits in non-institutionalized populations. It contains 26 items measured on a four-point Likert scale. Sixteen items measure ‘primary’ traits, including selfishness and a lack of care for others, and the remaining items tap ‘secondary’ traits, which include proneness to boredom and impulsivity. Internal consistency in the present study was Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for the primary subscale (P-LSRP) and 0.70 for the secondary subscale (S-LSRP). There is no recommended clinical cut-off for the LSRP.

The Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE)

The 42-item CAPE questionnaire55 is a reliable measure for the assessment of the expression of psychosis dimensions in clinical and research settings. Positive psychotic experiences were assessed using the CAPE’s 20-item positive subscale (CAPEp). The internal consistency of this subscale in this study is good (Cronbach’s α = 0.74). Although there is not a well-established cut-off score for the CAPEp, a score of 50 has been shown to have some validity56.

The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

The AQ29 consists of 50 items that measure the presence of traits associated with the autistic spectrum within the general population. Each item is given a score of 0 or 1. The AQ’s internal consistency in this study is good (Cronbach’s α = 0.71). A score of 32 has been recommended as a clinical cut-off for the AQ57.

The National Adult Reading Test (NART)

The NART58 consists of 50 words of irregular pronunciations. The total number of correct pronunciations is used to predict the full, verbal and performance Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) IQ59.

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised (CESD-R)

The CESD-R60 is a 20-item self-report scale that closely reflects the DSM-IV criteria for depression, and assesses the individual’s level of depressive symptomatology experienced over the last two weeks. The internal consistency in this study is excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.95). Although a score equal to or above 16 has been recommended for identifying a person at risk for clinical depression, this value has been criticised for producing too many false positives61.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brothers, L. & Ring, B. A neuroethological framework for the representation of minds. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 4, 107–118 (1992).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. & Aharon-Peretz, J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective theory of mind: A lesion study. Neuropsychologia 45, 3054–3067 (2007).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Tomer, R., Berger, B. D., Goldsher, D. & Aharon-Peretz, J. Impaired “affective theory of mind” is associated with right ventromedial prefrontal damage. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 18, 55–67 (2005).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Tibi-Elhanany, Y. & Aharon-Peretz, J. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is involved in understanding affective but not cognitive theory of mind stories. Social Neuroscience 1, 149–166 (2006).

Sebastian, C. L. et al. Neural processing associated with cognitive and affective Theory of Mind in adolescents and adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 7, 53–63 (2011).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. The neural bases for empathy. The Neuroscientist 17, 18–24 (2011).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Harari, H., Aharon-Peretz, J. & Levkovitz, Y. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in affective theory of mind deficits in criminal offenders with psychopathic tendencies. Cortex 46, 668–677 (2010).

Baron‐Cohen, S. Autism: the empathizing–systemizing (E‐S) theory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1156, 68–80 (2009).

Abu-Akel, A., Shamay-Tsoory, S. Characteristics of theory of mind impairments in schizophrenia. In Social cognition in schizophrenia: from evidence to treatment (ed. Roberts, D. L. & Penn, D. L.) 196–214 (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Bora, E., Yucel, M. & Pantelis, C. Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research 109, 1–9 (2009).

Abu-Akel, A. M., Wood, S. J., Hansen, P. C., & Apperly, I. A. Perspective-taking abilities in the balance between autism tendencies and psychosis proneness. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282, doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0563 (2015).

Abu-Akel, A., Heinke, D., Gillespie, S. M., Mitchell, I. J. & Bo, S. Metacognitive impairments in schizophrenia are arrested at extreme levels of psychopathy: the cut-off effect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 124, 1102–1109 (2015).

Chisholm, K., Lin, A., Abu-Akel, A. & Wood, S. J. The association between autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a review of eight alternate models of co-occurrence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 55, 173–183 (2015).

Leno, V. C. et al. Callous–unemotional traits in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.159863 (2015).

Kincaid, D. L., Doris, M., Shannon, C. & Mulholland, C. What is the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder and ASD traits in psychosis? A systematic review. Psychiatry Research 250, 99–105 (2017).

Larson, F. V. et al. Psychosis in autism: comparison of the features of both conditions in a dually affected cohort. The British Journal of Psychiatry 210, 269–275 (2017).

Gray, K., Jenkins, A. C., Heberlein, A. S. & Wegner, D. M. Distortions of mind perception in psychopathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 477–479 (2011).

Gillespie, S. M., Rotshtein, P., Wells, L. J., Beech, A. R., & Mitchell, I. J. Psychopathic traits are associated with reduced attention to the eyes of emotional faces among adult male non-offenders. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00552 (2015).

Gökçen, E., Frederickson, N. & Petrides, K. V. Theory of mind and executive control deficits in typically developing adults and adolescents with high levels of autism traits. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46, 2072–2087 (2016).

Lockwood, P. L., Bird, G., Bridge, M., & Viding, E. Dissecting empathy: high levels of psychopathic and autistic traits are characterized by difficulties in different social information processing domains. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00760 (2013).

Hare, R. D. The Hare psychopathy checklist-revised: second edition. (Multi-Health Systems, 2003).

Dawel, A., O’Kearney, R., McKone, E. & Palermo, R. Not just fear and sadness: Meta-analytic evidence of pervasive emotion recognition deficits for facial and vocal expressions in psychopathy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 36, 2288–2304 (2012).

Brook, M. & Kosson, D. S. Impaired cognitive empathy in criminal psychopathy: Evidence from a laboratory measure of empathic accuracy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 122, 156–166 (2013).

Richell, R. A. et al. Theory of mind and psychopathy: can psychopathic individuals read the ‘language of the eyes’? Neuropsychologia 41, 523–526 (2003).

Ali, F. & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. Investigating theory of mind deficits in nonclinical psychopathy and Machiavellianism. Personality and Individual Differences 49, 169–174 (2010).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Baron-Cohen, S. Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind (MIT press, 1997).

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M. & Frith, U. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition 21, 37–46 (1985).

Baron‐Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high‐functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 42, 241–251 (2001).

Oakley, B. F., Brewer, R., Bird, G. & Catmur, C. Theory of mind is not theory of emotion: A cautionary note on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 125, 818–823 (2016).

Jones, A. P., Happé, F. G., Gilbert, F., Burnett, S. & Viding, E. Feeling, caring, knowing: different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 51, 1188–1197 (2010).

Pasalich, D. S., Dadds, M. R. & Hawes, D. J. Cognitive and affective empathy in children with conduct problems: Additive and interactive effects of callous–unemotional traits and autism spectrum disorders symptoms. Psychiatry Research 219, 625–630 (2014).

Gillespie, S. M., McCleery, J. P. & Oberman, L. M. Spontaneous versus deliberate vicarious representations: Different routes to empathy in psychopathy and autism. Brain: A Journal of Neurology 137(e272), 1–3 (2014).

O’Nions, E. et al. Examining the genetic and environmental associations between autistic social and communication deficits and psychopathic callous-unemotional traits. PLOS ONE 10, e0134331, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134331 (2015).

Rogers, J., Viding, E., Blair, R. J., Frith, U. & Happe, F. Autism spectrum disorder and psychopathy: shared cognitive underpinnings or double hit? Psychological Medicine 36, 1789–1798 (2006).

Schiffer, B. et al. Neural mechanisms underlying affective theory of mind in violent antisocial personality disorder and/or schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin doi:10.1093/schbul/sbx012 (2017).

Sharp, C. & Vanwoerden, S. Social cognition: Empirical contribution: The developmental building blocks of psychopathic traits: Revisiting the role of theory of mind. Journal of Personality Disorders 28, 78–95 (2014).

Dziobek, I. et al. Introducing MASC: A movie for the assessment of social cognition. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36, 623–636 (2006).

Smeets, T., Dziobek, I. & Wolf, O. T. Social cognition under stress: differential effects of stress-induced cortisol elevations in healthy young men and women. Hormones and Behavior 55, 507–513 (2009).

Spek, A. A. & Wouters, S. G. Autism and schizophrenia in high functioning adults: Behavioral differences and overlap. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 4, 709–717 (2010).

Hayes, A. F. & Matthes, J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods 41, 924–936 (2009).

Crespi, B. & Badcock, C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 31, 241–261 (2008).

Abu-Akel, A. & Bailey, A. L. The possibility of different forms of theory of mind impairment in psychiatric and developmental disorders. Psychological Medicine 30, 735–738 (2000).

Blair, R. J. R. Fine cuts of empathy and the amygdala: dissociable deficits in psychopathy and autism. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 61, 157–170 (2008).

Kiehl, K. A. et al. Limbic abnormalities in affective processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry 50, 677–684 (2001).

Gordon, H. L., Baird, A. A. & End, A. Functional differences among those high and low on a trait measure of psychopathy. Biological Psychiatry 56, 516–521 (2004).

Seara-Cardoso, A., Sebastian, C. L., Viding, E. & Roiser, J. P. Affective resonance in response to others’ emotional faces varies with affective ratings and psychopathic traits in amygdala and anterior insula. Social Neuroscience 11, 140–152 (2016).

Sebastian, C. L. et al. Neural responses to affective and cognitive theory of mind in children with conduct problems and varying levels of callous-unemotional traits. Archives of General Psychiatry 69, 814–822 (2012).

Smith, A. Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. Psychological Record 56, 3–21 (2006).

Smith, A. Emotional empathy in autism spectrum conditions: weak, intact, or heightened? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39, 1747–1748 (2009).

Bo, S., Abu-Akel, A., Kongerslev, M., Haahr, U. H. & Simonsen, E. Risk factors for violence among patients with schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review 31, 711–726 (2011).

Dolan, M. & Fullam, R. Theory of mind and mentalizing ability in antisocial personality disorders with and without psychopathy. Psychological Medicine 34, 1093–1102 (2004).

Dadds, M. R. et al. Learning to ‘talk the talk’: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50, 599–606 (2009).

Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A. & Fitzpatrick, C. M. Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68, 151–158 (1995).

Stefanis, N. C. et al. Evidence that three dimensions of psychosis have a distribution in the general population. Psychological Medicine 32, 347–358 (2002).

Boonstra, N., Wunderink, L., Sytema, S. & Wiersma, D. Improving detection of first-episode psychosis by mental health-care services using a self-report questionnaire. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 3, 289–295 (2009).

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J. & Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 31, 5–17 (2001).

Nelson, H. E., & Wilson, J. National Adult Reading Test (NART) (NFER-Nelson, 1991).

Crawford, J. R. et al. Estimating premorbid IQ from demographic variables: regression equations derived from a UK sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 28, 275–278 (1989).

Eaton, W. W., Smith, C., Ybarra, M., Muntaner, C., & Tien, A. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R) in The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: instruments for adults, 3rd edition, volume 3 (ed. Maruish, M. E.) 363–377 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004).

Van Dam, N. T. & Earleywine, M. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised (CESD-R): Pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Research 186, 128–132 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by a project grant from the Economic and Social Research Council [ES/L002337/1]. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Stella Pareas, Bessie McDonald-Phelps, and Beril Hassan for their help with data collection and data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.G., I.J.M. and A.A-A. designed the research; S.M.G. and A.A-A. analysed data; S.M.G., I.J.M. and A.A-A. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gillespie, S.M., Mitchell, I.J. & Abu-Akel, A.M. Autistic traits and positive psychotic experiences modulate the association of psychopathic tendencies with theory of mind in opposite directions. Sci Rep 7, 6485 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06995-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06995-2

This article is cited by

-

Schizotypy and psychopathic tendencies interactively improve misattribution of affect in boys with conduct problems

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2021)

-

Spanish Validation of the Autism Quotient Short Form Questionnaire for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019)

-

Does Affective Theory of Mind Contribute to Proactive Aggression in Boys with Conduct Problems and Psychopathic Tendencies?

Child Psychiatry & Human Development (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.