Abstract

Deep-sea scleractinian coral reefs are protected ecologically and biologically significant areas that support global fisheries. The absence of observations of deep-sea scleractinian reefs in the Central and Northeast Pacific, combined with the shallow aragonite saturation horizon (ASH) and high carbonate dissolution rates there, fueled the hypothesis that reef formation in the North Pacific was improbable. Despite this, we report the discovery of live scleractinian reefs on six seamounts of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and Emperor Seamount Chain at depths of 535–732 m and aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) values of 0.71–1.33. Although the ASH becomes deeper moving northwest along the chains, the depth distribution of the reefs becomes shallower, suggesting the ASH is having little influence on their distribution. Higher chlorophyll moving to the northwest may partially explain the geographic distribution of the reefs. Principle Components Analysis suggests that currents are also an important factor in their distribution, but neither chlorophyll nor the available current data can explain the unexpected depth distribution. Further environmental data is needed to elucidate the reason for the distribution of these reefs. The discovery of reef-forming scleractinians in this region is of concern because a number of the sites occur on seamounts with active trawl fisheries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seamounts with deep-sea scleractinian coral reefs fall into the classification of vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs) and ecologically and biologically significant areas (EBSAs), thus they receive special protection status, even on the high seas1. Deep-sea coral reefs are vulnerable to anthropogenic stresses, including fisheries trawling, which is known to destroy reef structures2 with recovery likely to take decades to centuries3, 4. In addition, anthropogenically induced shoaling of the aragonite saturation horizon (ASH), due to global climate change and ocean acidification, is expected to lead to loss of suitable habitat for slow-growing reef-forming coral species5. Thus, determining the locations of deep-sea scleractinian reef sites is important in fisheries management and aids in the development of local, national and international conservation and protection policies6.

Deep-sea scleractinian coral reefs are found throughout the North Atlantic and the South Pacific, but thus far have not been discovered in the Central and Northeast Pacific region. Instead, dense beds of octocorals and antipatharians dominate deep-sea hard substrates in this area7,8,9,10,11. Although there are many species of scleractinians in deep waters of the North Pacific, they are predominantly solitary cup corals or individual colonies, rather than the type that accumulate into reefs9, 12. The general absence of observations of deep-sea scleractinian reefs in the North Pacific, despite a reasonable amount of exploration, has led to the hypothesis that reef formation in the North Pacific is “unlikely, if not impossible”5. This hypothesis is based on two lines of reasoning: one is the relatively shallow ASH in the North Pacific (50–600 m) compared to other regions of the worlds’ oceans; the other is that carbonate dissolution rates in the North Pacific exceed those of the North Atlantic by a factor of two5, 13. Consistent with these observations, habitat suitability modeling for deep-sea scleractinians also shows very little suitable habitat in the North Pacific except for some scattered locations above the ASH14, 15.

Despite these expectations, here we report the discovery of live scleractinian reefs at six sites in the North Pacific on seamounts of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) and Emperor Seamount Chain (ESC) during an exploratory Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) survey to examine recovery of deep-sea coral communities following fisheries trawling at these sites. We compare the observed reef distribution to the available environmental data for the sites where they occur, including aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) and other abiotic factors, to gain insight into how reefs are able to form despite the challenging carbonate chemistry.

Results

Scleractinians reefs were observed on six of the 10 features within our surveyed depth range and occurred at depths of 535–732 m (the maximum depth surveyed) (Figs 1, 2 and 3, Table 1). The linear length of the reefs ranged from ~3–786 m. These values should be viewed as conservative estimates for reef length as the AUV employed in this study follows a preset course heading regardless of what is on the seafloor, as opposed to a survey with a research submersible or Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), which would map out the full extent of the reef.

Example AUV images of observed scleractinian reefs taken ~5 m above the bottom. The reef at (A). 641 m on Northwest Hancock and (B) 637 m on Southeast Hancock, were predominantly a species with orange polyps, most likely Solenosmilia. (C) The purple scleractinian reef, most likely formed by Enalopsammia, at 596 m on Yuryaku. Images obtained by the authors using the AUV Sentry.

The range of the available environmental parameters observed at the locations at which the scleractinian reefs occurred are summarized in Table 2. The occurrence of reef was shallower moving to the northwest along the seamount chain (Fig. 3A), with a statistically significant non-parametric Spearman Rank correlation (Rho = −0.389, p < 0.0001) between depth of occurrence and longitude. The Ωarag of seawater at the locations of the reef sites ranged from 0.71–1.33. The ASH deepens moving to the northwest along the NWHI and ESC chains, with the mean depth of scleractinian reefs at several sites falling below the ASH (Fig. 4).

Depth of the aragonite saturation horizon (ASH) at each site with the mean depth of occurrence of scleractinian reef for each site. Black squares are mean ASH depth for each site. White triangles are mean + 1 SD for reef occurrence depth. Note that the mean depth of reefs falls below the ASH for most sites.

Given the altitude above the seafloor at which the images were taken, the species identification of the scleractinians in most images could not be determined. The depth distribution curve for observed reef structure across sites (Fig. 3B) was bimodal suggesting at least 2 species are present. Based on the purple coloration of the polyps and colony morphology, Enalopsammia rostrata, a species known to occur at other sites in the Hawaiian Archipelago as individual colonies, was the likely reef-former at Academician, Kammu, Northwest Hancock and Yuryaku Seamounts (Fig. 2C). A second morphotype with orange polyps that is likely Solenosmilia variabilis was the abundant species on Koko and both Hancock Seamounts (Fig. 2A,B). At several sites both morphotypes occurred in the same images. We could not do a quantitative analysis of the distribution of either species separately because in many images the resolution was not sufficient to distinguish between them.

Principle Components Analysis (PCA) was performed to determine which environmental factors correlate most strongly with the distribution of scleractinian reefs. PCA shows that each site groups strongly with other points from the same seamount (Fig. 5). Scleractinian reefs sites occupy a small range of PCA axis 2, but a broad range of each of the other four PCA axes. PCA axis 2 was most strongly correlated with sound velocity and the east-west component of the surface current velocity (‘u’), suggesting currents may be the most influential of the measured factors on the occurrence of scleractinian reefs (Table 3). There is a clear shift in current direction near the location where the reefs begin, with westward currents dominating to the southeast and eastward currents dominating to the northwest (Fig. 6A).

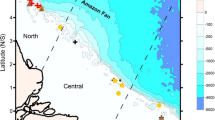

(A) One year average (2015–2016) raster of the eastward surface water velocity (u) across the study area. Positive values (blue) show predominance of eastward currents. Negative values (red) represent westward prevailing currents. Figure created using ArcMap 10.4.1 using HYCOM data as described in the methods. (B) Eight year average composite raster of surface chlorophyll-a concentration (2008–2016). Black contour delimits 0.07 mg/m3 chl-a concentration. Figure created using ArcMap 10.4.1 using satellite data obtained from Aqua-MODIS satellite available on the ERDDAP42 data set as described in the methods. In both panels white circles indicate the location of transects with scleractinian reefs and stars indicate transects which did not include reef structures.

Discussion

Extensive explorations from Bank 11 to the southeast in the NWHI had so far not discovered any deep-sea coral reefs, even though both submersible dives and ROV explorations had included the same depth zones at several different islands and seamounts11. Indeed, it was thought to be improbable that scleractinian reefs would occur in the North Pacific due to carbonate chemistry that is expected to make reef formation and accumulation challenging. The carbonate dissolution rate in the North Pacific peaks between 400–600 m then decreases rapidly with depth13. This depth range overlaps with the relatively shallow range of the ASH in the North Pacific (50–600 m). Thus, theoretically, the most challenging depth range for reef formation in the North Pacific would begin somewhere around 600 m depth, and continue deeper. Yet, here we document observations of reefs at six seamounts in the NWHI and ESC at depths of 535–732 m.

This begs the question, how is it that the reefs can occur at these sites? One potential insight comes from a closer examination of the ASH depth in Feely et al.13, which indicates that the ASH becomes deeper moving to the northwest along the NWHI (confirmed by our results in Fig. 4). This suggests that, if the reef-forming species have a narrow depth range tolerance, the likelihood of finding reefs would increase moving to the northwest along the NWHI. That is indeed what we found, reefs were observed on every feature explored to the northwest of Academician Berg except Bank 11. However, if the ASH were the main factor governing the distribution of these corals, we would expect their depth range to stay the same or deepen moving northwest along the chain, paralleling the ASH. Instead the observed depth range becomes shallower. Further, a number of reef sites also occur below the ASH, with measured Ωarag values of 0.71–1.33, together these suggest the ASH is not the primary controlling factor for the distribution of reefs.

Although the ASH would be expected to be a limiting factor for calcifying deep-sea coral species that produce aragonite5, results are mixed with respect to the response of calcifying species to low Ωarag and pH. Supporting the idea that the ASH would be limiting, laboratory CO2 exposure experiments have shown that calcification rates of deep-sea corals decrease with decreasing Ωarag 16,17,18,19,20, that deep-sea corals produce skeletons that are more susceptible to erosion under low Ωarag conditions21, and that net dissolution occurs in live corals in undersaturated (Ωarag < 1) waters18,19,20. However, other experimental studies have shown no response in calcification and respiration rates to changing Ωarag 19, 22, 23, and it has been well documented that deep-sea corals can live and calcify in undersaturated waters24, 25. For example, Thresher et al.24 also found a number of deep-sea corals on seamounts south of Tasmania living below the ASH and calcite saturation horizon. An important exception that they note though is that the reef-forming scleractinians, including Enalopsammia and Solenosmilia, were limited to depths “saturated or near saturated” with respect to aragonite. In contrast, we find scleractinian reefs in waters with Ωarag well below 1 in the NWHI and ESC.

In fact, a number of studies have suggested that some deep-sea coral species have physiological mechanisms to compensate for undersaturation and to maintain their calcifying processes and internal pH25,26,27. For example, Thresher et al.24 postulated that the non-reef forming scleractinian corals below the ASH might be able to survive due to high regional productivity resulting in an abundant food supply. This food supply could provide the excess energy needed for calcification in undersaturated waters. In contrast, Maier et al.18 found that feeding in laboratory experiments did increase calcification rates of the Mediterranean deep-sea coral Madrepora oculata at ambient Ωarag, but feeding had no effect on calcification rates under low Ωarag conditions. While the authors attribute this to the small fraction (1–3%) of the total metabolic energy demand required for calcification in Madrepora oculata, this does not explain why feeding appears to have enhanced calcification at ambient Ωarag. Georgian et al.28 found that net calcification, respiration and prey capture rates of Lophelia pertusa from the Gulf of Mexico decreased with decreasing pH and Ωarag but, in the same species from Norway, respiration and prey capture rates increased, and calcification only decreased slightly with declining Ωarag. These results suggest that local environmental conditions, including food supply, could result in regional differences in the ability of deep-sea corals to adapt and/or acclimate to ocean acidification.

While the main Hawaiian Islands and much of the NWHI are located in oligotrophic waters, there is a transition to higher chlorophyll waters moving to the northwest, characterized by a front referred to as the Transition Zone Chlorophyll Front (TZCF). The position of this front varies seasonally and annually, crossing the Archipelago somewhere near 180° longitude in the years it reaches its maximum extent29, very close to our southeastern most site with reefs, Academician Berg at 178.84°W. Figure 6B shows the annual mean surface water chlorophyll concentration across this region averaged over the period 2008–2016. Sites with reefs have higher mean annual chlorophyll than those without. Thus higher chlorophyll, while not an explanation for why the corals occur shallower, could at least be a plausible explanation for why these reefs occur from Academician and further northwest. Consistent with this, PCA analyses indicates that particulate organic carbon (POC) and Chlorophyll a (Chl-a) were most strongly correlated with PCA axis 1 (Fig. 5, Table 3). However, sites with scleractinians were distributed broadly across the PCA 1 axis, suggesting that potential food supply alone cannot explain the distribution of these reefs.

Of the five PCA axes, transects with scleractinian reefs occupied a very narrow range of PCA axis 2 when graphed relative to the four other axes. PCA axis 2 was most strongly correlated with sound velocity and the east-west component of surface currents. This suggests there is a very narrow range of current velocity needed for the survival of the deep-sea scleractinian reef-forming species. That currents might be tied to the distribution of deep-sea coral reefs is not at all surprising because the occurrence of corals near topographic highs with maximum current velocities has been recognized since some of the earliest work on seamounts30. However many other transects without reefs also fell within the same range of the PCA 2 axis as the scleractinian reef sites, suggesting currents are also not the only factor critical for reef occurrence. In addition, surface current data may not necessarily represent what the corals are experiencing at depth and alone could not explain why the depth distribution of reefs decreases to the northwest.

More research is clearly needed to explain the distribution of these reefs. Ideally we would use species distribution modeling to analyze the factors most correlated with the distribution of these species as well as to determine the locations of possible areas of suitable habitat14, 15, 31, but we currently do not have high enough resolution data for key parameters that would go into such modeling, in particular backscatter, in situ currents, and other important factors.

The occurrence of the observed coral reefs in the NWHI and ESC was limited to sites located outside the pre-2016 expansion boundaries of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, including several seamounts with active trawling. This raises concern for protection of these fragile habitats and the question of what their extent might have been in this region prior to trawling. Additionally, the long-term response to increasing seawater CO2 levels by marine calcifying organisms susceptible to ocean acidification32 is a major concern for the management and conservation of corals. Determining the tie of these species distributions to Ωarag is becoming time-critical because the ASH is expected to continue shoaling in this region as anthropogenic CO2 continues to increase in the atmosphere and ocean5, 33, which could further limit suitable habitat and thus threaten reef-forming scleractinians.

Methods

As part of a project examining the recovery potential of deep-sea coral communities impacted by trawling in the NWHI and ESC, we explored 10 seamounts at depths of 200–700 m using the AUV Sentry during cruises in 2014 and 2015 (Table 1, Fig. 1). On each seamount three sides of the seamount were surveyed and on each side, replicate photo transects of 1000 m length were conducted. During image transects, the speed of the AUV was 0.5–0.7 m/s and the vehicle was approximately 5 m above the bottom.

All images taken during and between transects were scanned for presence of scleractinian reefs using enlarged thumbnails on a Macintosh computer. Images with scleractinians were then viewed more closely in Preview v 7.0 (Apple Inc.) and categorized into one of four categories – “Definite live reef” – which included images of reef that had visible open polyps; “Likely live reef” – images of reef with no visible polyps but areas of lighter colored skeleton similar to the skeleton found on the colonies with live polyps. Generally these images also occurred in proximity to images with definitely live reef. “Reef patches” – areas with smaller clusters of colonies that appeared live but did not form a continuous reef structure, and “Coral rubble” – areas with an accumulation of scleractinian coral skeleton fragments but no evidence of live colonies. For the environmental analyses, only images that fell into the first three categories were used.

Environmental data for the seamounts were obtained from several sources. A Seabird SBE49 Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) with a Seapoint optical backscatter (OBS) sensor and a Anderaa optode (model 4330) oxygen concentration sensor on the AUV Sentry provided in situ temperature, salinity, depth, dissolved oxygen and turbidity data that was linked directly to each image that was taken.

A Sea-Bird Electronics, Inc. (SBE) 911plus conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) instrument with a rosette of twenty-four 10 L Niskin bottles was used to record water column environmental profiles and collect water samples. The CTD included sensors to measure temperature, salinity, pressure, sound velocity (Chen-Millero [m/s]), dissolved oxygen (SBE 43 [μmol/l]), and fluorescence (Wetlab ECO-AFL/FL [mg/m3]). The hydrocasts were conducted down to 800 to 1200 m water depth as close to the AUV survey areas as possible, typically within 1–4 km. At each site, at least one “high resolution” profile was completed with water samples taken at uniform standard depths (5, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000, 1200 m) with the final sample taken as near to the bottom as possible (~25 m off of the bottom). At least 3 Niskin bottles were used as duplicate samples. Additional “low resolution” profiles with water samples taken at 5, 125, 300, 700 and 1000 m and CTD only characterizing profiles were made at additional locations around the site to characterize the local heterogeneity. All hydrographic data were processed using the SBE data processing software using current manufacture calibrations. The locations, water depths, and sampling depths are listed in Table 1.

Dissolved nutrient seawater samples collected at each CTD station were stored in acid-cleaned high-density polyethylene 20 mL scintillation vials. Vials were rinsed and triple filled with sample seawater before saving the final sample for analysis. Samples were immediately frozen until analyzed at the Geochemical and Environmental Research Group at Texas A&M University, College Station. Nutrient samples were analyzed on an Astoria-Pacific auto-analyzer using nitrate/nitrite/silicate methods based on Armstrong et al.34; phosphate methods based on Bernhardt and Wilhelms35; and ammonium methods based on Harwood and Kuhn36. The dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) concentrations were calculated as the sum of nitrite, nitrate, and ammonium concentrations. Analytical detection limits were 0.01 μM for phosphate, 0.003 μM for nitrite, 0.05 μM for nitrate and silicate, and 0.08 μM for ammonium.

Discrete water samples were collected from Niskin bottles for total alkalinity (TA) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) measurements into 250 ml borosilicate glass bottles by rinsing and triple filling, taking care to prevent bubbles in the sampling tubing and bottles. Water samples were preserved with 100 µl of saturated mercuric chloride (HgCl2) and ground glass stoppers were sealed with Apeizon grease and electrical tape. TA and DIC analyses were performed with a Versatile Instrument for the Determination of Titration Alkalinity (VINDTA) produced by Marianda Marine Analytics and Data. The VINDTA uses coulometric titration for DIC analysis and an open cell potentiometric titration for TA analysis. DIC and TA measurements were standardized with certified reference materials obtained from Andrew Dickson at Scripps Institution of Oceanography37, 38. Analyses of replicate samples yielded a mean precision of approximately 2.5 μmol kg−1 and 2 μmol kg−1 for DIC and TA analyses, respectively. The full seawater CO2 system was calculated using in-situ salinity, temperature, TA, and DIC data using an Excel Workbook Visual Basic for Applications translation of the original CO2SYS program39 by Pelletier, Lewis, and Wallace at the Washington State Department of Ecology, Olympia, WA. The CO2SYS program was run with carbonate constants from Mehrbach et al.40 refit by Dickson and Millero41.

Surface Chl-a and POC were extracted from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Environmental Research Division’s Data Access Program (ERDDAP) Data Set42. Surface current (zonal (u, east-west) and meridional (v, north-south)) data were extracted from HYCOM (HYbrid Coordinate Ocean Model). Daily values of surface current data (1/12 degree resolution) were extracted from January 1, 2015 to January 1, 2016. Monthly composites of surface Chl-a (0.025 degree resolution) and POC (4 km resolution) data were derived from Aqua-MODIS satellite from January 2008 to December 2016. All data (*.NetCDF) were imported into Matlab for quality control and then exported into ArcMap (10.4.1)43 to calculate raster statistics (average, maximum, and minimum) for all data sets.

Seafloor bathymetric and backscatter data was collected by Kongsberg EM122 multibeam echo sounders during cruises in 2014–2015 on R/V Falkor, R/V Sikuliaq, and R/V Kilo Moana. Processed bathymetric data were imported into QGIS and then analyzed for slope and roughness. Slope was calculated as a percentage and measures the inclination to the horizontal. Roughness is calculated by the largest bathymetric difference between a central pixel and its surround cells in a 3 × 3 grid44. Point vector layers of AUV Sentry transects were overlaid onto the slope, roughness, and backscatter layers and data from those layers were extracted into the transect points. Values were then averaged for a final per transect measurement.

Summary statistics for the environmental data and determination of depth distributions were completed in JMP pro v 12.0.145. These analyses included all images with scleractinian reefs, regardless of whether they were taken on a transect or during transits between transects. Oceanographic CTD profiles were plotted using Ocean Data View software46.

To try to tease out what environmental factors were most correlated with scleractinian distributions, we performed a PCA including all transects from the AUV Sentry regardless of scleractinian presence or absence. We did not include data for transits between the transects in the PCA. Environmental data for the PCA plot were log (x + 1) transformed and normalized in Primer v. 7.047. Draftsmen plots showed a strong correlation among many of the environmental variables even after transformation and normalization. Thus the environmental data was reduced by eliminating 1 environmental variable out of each pair with a >90% correlation (Supplemental Table 1). Correlational PCA was then completed in PRIMER using 22 environmental variables.

References

Parker, S. J., Penney, A. J. & Clark, M. R. Detection criteria for managing trawl impacts on vulnerable marine ecosystems in high seas fisheries of the South Pacific Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 397, 309–317 (2009).

Clark, M. R. & Rowden, A. A. Effect of deepwater trawling on the macro-invertebrate assemblages of seamounts on the Chatham Rise, New Zealand. Deep-Sea Res. I. 56, 1540–1554 (2009).

Althaus, F. et al. Impacts of bottom trawling on deep-coral ecosystems of seamounts are long-lasting. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 397, 279–294 (2009).

Williams, A. et al. Seamount megabenthic assemblages fail to recover from trawling impacts. Mar. Ecol. 31, 183–199 (2010).

Guinotte, J. M. et al. Will human-induced changes in seawater chemistry alter the distribution of deep-sea scleractinian corals? Front. Ecol. Environ. 4, 141–146 (2006).

Ardron, J. A. et al. A systematic approach towards the identification and protection of vulnerable marine ecosystems. Mar. Policy 49, 146–154 (2014).

Parrish, F. A. & Baco, A. R. In The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States: 2007 (eds Lumsden, S. E., Hourigan, T. F., Bruckner, A. W. & Dorr, G.) 115–194 (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2007).

Baco, A. R. Exploration for deep-sea corals on north Pacific seamounts and islands. Oceanography 20, 108–117 (2007).

Cairns, S. D. Deep-water corals: an overview with special reference to diversity and distribution of deep-water scleractinian corals. Bull. Mar. Sci. 81, 311–322 (2007).

Stone, R. P. & Shotwell, S. K. In The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States (eds Lumsden, S. E., Hourigan, T. F., Bruckner, A. W. & Dorr, G.) 65–108 (NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP-3, 2007).

Parrish, F. A., Baco, A. R., Kelley, C. & Reiswig, H. In The State of Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems of the United States (eds Hourigan, T. F., Etnoyer, P. J. & Cairns, S. D.) 1–38 (NOAA Technical Report, 2015).

Whitmire, C. E. & Clarke, M. E. In The State of Deep Coral Ecosystems of the United States (eds Lumsden, S. E., Hourigan, T. F., Bruckner, A. W. & Dorr, G.) 109–154 (NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP-3, 2007).

Feely, R. A. et al. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science 305, 362–366 (2004).

Tittensor, D. P. et al. Predicting global habitat suitability for stony corals on seamounts. J. Biogeogr 36, 1111–1128 (2009).

Davies, A. J. & Guinotte, J. M. Global habitat suitability for framework-forming cold-water corals. PloS One 6, e18483 (2011).

Maier, C., Hegeman, J., Weinbauer, M. G. & Gattuso, J.- Calcification of the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa, under ambient and reduced pH. Biogeosciences 6, 1671–1680 (2009).

Maier, C., Watremez, P., Taviani, M., Weinbauer, M. G. & Gattuso, J. P. Calcification rates and the effect of ocean acidification on Mediterranean cold-water corals. Proc. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 279, 1716–1723 (2012).

Maier, C. et al. Effects of elevated pCO2 and feeding on net calcification and energy budget of the Mediterranean cold-water coral Madrepora oculata. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3208–3217 (2016).

Form, A. U. & Riebesell, U. Acclimation to ocean acidification during long‐term CO2 exposure in the cold‐water coral Lophelia pertusa. Global Change Biol. 18, 843–853 (2012).

Lunden, J. J., McNicholl, C. G., Sears, C. R., Morrison, C. L. & Cordes, E. E. Acute survivorship of the deep-sea coral Lophelia pertusa from the Gulf of Mexico under acidification, warming, and deoxygenation. Front. Mar. Sci. 1, 78 (2014).

Hennige, S. J. et al. Hidden impacts of ocean acidification to live and dead coral framework. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 282, 20150990 (2015).

Maier, C. et al. End of the century pCO2 levels do not impact calcification in Mediterranean cold-water corals. PloS One 8, e62655 (2013).

Maier, C. et al. Respiration of Mediterranean cold-water corals is not affected by ocean acidification as projected for the end of the century. Biogeosciences 10, 5671–5680 (2013).

Thresher, R. E., Tilbrook, B., Fallon, S., Wilson, N. C. & Adkins, J. Effects of chronic low carbonate saturation levels on the distribution, growth and skeletal chemistry of deep-sea corals and other seamount megabenthos. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 442, 87–99 (2011).

Lebrato, M. et al. Benthic marine calcifiers coexist with CaCO3‐undersaturated seawater worldwide. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1038–1053 (2016).

Dupont, S., Dorey, N., Stumpp, M., Melzner, F. & Thorndyke, M. Long-term and trans-life-cycle effects of exposure to ocean acidification in the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis. Mar. Biol. 160, 1835–1843 (2013).

Wood, S. et al. El Nino and coral larval dispersal across the eastern Pacific marine barrier. Nature Communications 7, 1–11 (2016).

Georgian, S. E. et al. Biogeographic variability in the physiological response of the cold‐water coral Lophelia pertusa to ocean acidification. Mar. Ecol. 37, 1345–1359 (2016).

Baker, A. R. et al. Dry and wet deposition of nutrients from the tropical Atlantic atmosphere: Links to primary productivity and nitrogen fixation. Deep Sea Res. I 54, 1704–1720 (2007).

Genin, A., Dayton, P. K., Lonsdale, P. F. & Spiess, F. N. Corals on seamount peaks provide evidence of current acceleration over deep-sea topography. Nature 322, 59–61 (1986).

Silva, M. & MacDonald, I. R. The mesophotic coral habitat in northeastern Gulf of Mexico: Suitability Modeling. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. (in review).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742 (2007).

Feely, R. A. et al. Decadal changes in the aragonite and calcite saturation state of the Pacific Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3001 (2012).

Armstrong, F. A. J., Stearns, C. R. & Strickland, J. D. H. The measurement of upwelling and subsequent biological process by means of the Technicon Autoanalyzer® and associated equipment (Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts Ser. 14, Elsevier, 1967).

Bernhardt, H. & Wilhelms, A. The continuous determination of low level iron, soluble phosphate and total phosphate with the AutoAnalyzer (Technicon Symposia Ser. 1, 1967).

Harwood, J. E. & Kühn, A. L. A colorimetric method for ammonia in natural waters. Water Res 4, 805–811 (1970).

Dickson, A. G. Reference material for oceanic CO2 measurements. Oceanography 14, 21–22 (2001).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. In Guide to best practices for ocean CO 2 measurements. (North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 2007).

Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. In Program developed for CO 2 system calculations (Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, managed by Lockheed Martin Energy Research Corporation for the US Department of Energy Tennessee, 1998).

Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C., Hawley, J. E. & Pytkowik, R. Measurement of apparent dissociation-constants of carbonic-acid in seawater at atmospheric-pressure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 6, 897–907 (1973).

Dickson, A. G. & Millero, F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep Sea Res. A 34, 1733–1743 (1987).

Simons, R. A. ERDDAP–The Environmental Research Division’s Data Access Program. Available at http.coastwatch.pfeg.noaa.gov/erddap [2016] (2011).

ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.4.1 Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute (2016).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS 2.14.3 Geographic Information System User Guide. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Electronic document: http://docs.qgis.org/2.14/en/docs/user_manual (2016).

SAS Institute Inc., JMP®, Version 12.0.1. Cary, NC (1989–2007).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View. 2012. (2015).

Clarke, K. R. & Gorley, R. N. In Getting started with PRIMER V7 (Plymouth, Plymouth Marine Laboratory, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the crew of the RV Sikuliaq and RV Kilo Moana as well as the AUV Sentry team. Shamberger NSF REU students Jahna Brooks and Ashley Davis assisted with carbonate chemistry analyses. Arvind Shantharam, Mackenzie Schoemann, and John Schiff provided assistance at sea. Stephen Cairns and Sandra Brooke assisted with tentative identifications of the scleractinian images. Ron Etter, Markus Huettel, Sven Kranz and Mike Stukel provided valuable discussion on regression statistics. This work was conducted through support from NSF grant #s OCE-1334652 to ARB and OCE-1334675 to EBR. Work in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument was permitted under permit #PMNM-2014-028. We used the publicly available output from http://hycom.org. Funding for the development of HYCOM has been provided by the National Ocean Partnership Program and the Office of Naval Research. Data assimilative products using HYCOM are funded by the U.S. Navy. Computer time was made available by the DoD High Performance Computing Modernization Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: A.R.B., E.B.R., designed research; N.M., E.B.R., A.R.B., K.M., performed field research; N.B.M. and A.R.B. analyzed images, K.E.F.S., K.M., E.B.R., analyzed water column chemistry; M.S. obtained and analyzed chlorophyll, POC and surface current data; A.R.B. compiled and analyzed the datasets; A.R.B., N.B.M., M.S., K.E.F.S. and E.B.R. wrote the manuscript.; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baco, A.R., Morgan, N., Roark, E.B. et al. Defying Dissolution: Discovery of Deep-Sea Scleractinian Coral Reefs in the North Pacific. Sci Rep 7, 5436 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05492-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05492-w

This article is cited by

-

Population genetic structure of the deep-sea precious red coral Hemicorallium laauense along the Hawaiian Ridge

Marine Biology (2023)

-

Natural variability in seawater temperature compromises the metabolic performance of a reef-forming cold-water coral with implications for vulnerability to ongoing global change

Coral Reefs (2022)

-

The Northeast Atlantic is running out of excess carbonate in the horizon of cold-water corals communities

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.