Abstract

A working group from the Global Library of Underwater Biological Sounds effort collaborated with the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) to create an inventory of species confirmed or expected to produce sound underwater. We used several existing inventories and additional literature searches to compile a dataset categorizing scientific knowledge of sonifery for 33,462 species and subspecies across marine mammals, other tetrapods, fishes, and invertebrates. We found 729 species documented as producing active and/or passive sounds under natural conditions, with another 21,911 species deemed likely to produce sounds based on evaluated taxonomic relationships. The dataset is available on both figshare and WoRMS where it can be regularly updated as new information becomes available. The data can also be integrated with other databases (e.g., SeaLifeBase, Global Biodiversity Information Facility) to advance future research on the distribution, evolution, ecology, management, and conservation of underwater soniferous species worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Numerous aquatic and semi-aquatic species, including amphibians, annelids, cephalopods, cetaceans, crustaceans, fishes, pinnipeds, reptiles, and sirenians, use sound underwater for information acquisition and dissemination1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Sounds produced intentionally for the purposes of communication or navigation (i.e., active sounds), and incidentally through other activities (i.e., passive sounds) may both serve numerous ecological functions5,12,13, such as for environmental sensing14, predator or prey detection15,16,17, and competition18,19. Additionally, the remote sensing of these sounds through passive acoustic monitoring (i.e., an observational method to detect and characterize sounds) has applications for invasive species detection20,21, habitat and species management22,23, ecological monitoring24, and optimization of aquaculture operations25, among other possible uses. Underwater sounds and their uses nonetheless face increasing threats from human activities and resulting environmental degradation26,27,28,29,30.

Despite decades of research, documentations of underwater sonifery across different taxa remain highly variable. For example, the majority of whales, dolphins, and porpoises have been confirmed to produce sound31. In contrast, fishes and underwater invertebrates have been relatively less studied when considering the thousands of extant species5,32,33. There have been several recent efforts to review sound production information for larger taxonomic groups globally (e.g., marine mammals31, marine invertebrates33, fishes34), but these have varied in their approaches and definitions of sonifery. As such, a comprehensive inventory of all known underwater soniferous species remains lacking, limiting the ability to document, summarize, or quantify trends in global underwater sound production35.

To address previous data limitations, the effort to create a Global Library of Underwater Biological Sounds (GLUBS)35 in collaboration with the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) created a dataset of information on likely or documented underwater sonifery in aquatic species. The World Register of Marine Species (available at MarineSpecies.org) provides a comprehensive, searchable database of known marine organisms and other taxa, featuring taxonomic information—including numerous accepted, synonymized, misspelled, and unaccepted classifications—along with a growing list of ecological attributes and traits36,37,38. Through its own datasets and connections or associations with other global datasets (e.g., the Ocean Biogeographic Information System, OBIS), the data presented on WoRMS can be used to answer a variety of questions related to distribution, evolution, ecology, management, conservation, and other fields worldwide36. The WoRMS database is widely used among researchers, with consistent growth in visitors since its inception in 2007, and at least 7,000 publications that have cited or mentioned WoRMS and its related registers37,39. As part of ongoing initiatives related to the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) and Above and Beyond - Completing the World Register of Marine Species (ABC WoRMS), WoRMS is encouraging the documentation of species traits to better aid ecological research and provide more comprehensive information to its diverse user base40. Trait information on underwater sonifery by aquatic and semi-aquatic species is in service of these goals.

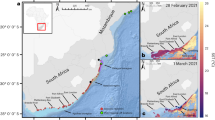

Here, we present a global inventory of 33,462 aquatic and semi-aquatic species and subspecies categorized based on known underwater sound production. To create this dataset, we integrated existing sources for fishes, mysticetes, and odontocetes, and we conducted additional literature surveys for other semi-aquatic and aquatic taxa (Fig. 1). This trait has six categories according to whether a species has been confirmed or is considered likely to produce sound based on the available scientific literature (Table 1) following established definitions of active and passive sound production in natural and unnatural conditions, among other terms (Table 2). We found 729 species documented as producing active and/or passive sounds under natural conditions, with another 21,911 species deemed likely to produce sounds based on evaluated taxonomic relationships (Fig. 2). This dataset is available in the figshare data repository and WoRMS.

Conceptual diagram of the data collection methods used to create a dataset of species categorized by known sonifery. For the marine mammals, other tetrapods, and fishes, species and subspecies in each taxa were established based on the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) database, which were subsequently categorized based on existing sources and additional online literature searching. For invertebrates, online literature searching identified species that had been studied for their sound production, which were then matched to their appropriate listing on the WoRMS database. The resulting dataset was then published on WoRMS and figshare.

Methods

Trait and category definitions

The ecological trait, ‘species exhibits underwater soniferous behavior,’ and its respective categories were defined by a working group of seven scientists, all experts in bioacoustics and the research literature of a variety of aquatic taxa including mammals, fishes, and invertebrates. The various definitions were largely adapted from other recent works (e.g., ancestral state reconstruction41; active sounds5). We also considered whether sounds were produced naturally, based on long-standing concerns of artificial instigation creating unnatural or involuntary sound production behaviors42,43,44. We defined sounds produced under natural conditions as those made in the absence of artificial manipulation, such as an electrical current or direct handling, but may have included sounds made in captive environments, such as tanks. The resulting table of the trait, categories, and definitions were then reviewed and approved by the WoRMS Data Management Team. The trait and category definitions created are listed in Table 1 and additional definitions of terms are provided in Table 2.

Data collection

Our data collection efforts centered on extant species and subspecies as listed on WoRMS. We separated taxa into four groupings for the purposes of our data collection. These groupings allowed us to better respond to the wide disparities in species richness, numbers of publications on sound production, and the existence of soniferous species reviews and inventories for the different taxa (Fig. 1).

Marine mammals

In this context, ‘marine mammals’ refers to fully aquatic marine mammal species and subspecies within the infraorder Cetacea or order Sirenia. All other mammal species for this dataset were examined as ‘other tetrapods.’ We used WoRMS38 as our taxonomic authority and queried the WoRMS database for a list of all accepted, extant marine mammal species and subspecies to base our data collection on, encompassing 148 species and subspecies.

Marine mammal ecological trait categorizations were largely based on work conducted for an upcoming Springer book on Marine Mammal Bioacoustics by Erbe and colleagues, which will provide an overview of sound production in marine mammals. There are many hundreds of publications on the active sounds produced by marine mammals, and their sounds have been summarized in several reviews on specific species groups or regions (e.g., Erbe et al.45). Therefore, it was not necessary to undertake a comprehensive literature search for every species. Rather, for each species and subspecies, we aimed to cite a recent review or summary of its sounds; a publication that documented a great variety of sounds; or one of the original or earliest publications of its sounds—in this order. As WoRMS somewhat differed from other marine mammal taxonomic authorities, such as the Society of Marine Mammalogy46, and the taxonomy associated with marine mammals is in ongoing flux, we also provided geographic areas associated with each species or subspecies based on the publications cited. We only focused on marine mammal active sound production for this review.

There were 19 species and subspecies—mostly offshore, cryptic species, such as some beaked whales (e.g., Berardius minimus)—whose sounds were not reported in available reviews or summaries. For these species, we searched Web of Science47 and Google Scholar48 for reports on their sound production in the peer-reviewed and grey literature. No records of their sounds were found. Based on the documented sounds for species within the same genera or families of these species, all these species with undocumented sound production were deemed ‘likely to produce sound under natural conditions, but unconfirmed’ (i.e., Category 3).

Other tetrapods

For the purposes of this dataset, ‘other tetrapods’ can be summarized as aquatic and semi-aquatic species and subspecies that occur in the following taxa groups: amphibians, hippopotamids, murids, mustelids, penguins, pinnipeds, ursids, and reptiles including crocodilians, lacertids, serpents, and testudines. For each of these groups of taxa, we queried the WoRMS38 database for a list of all accepted, extant marine species and subspecies. Though marine was specified, WoRMS defines ‘marine’ generously, so our taxa also included species that may predominantly live in and around brackish or fresh water or that may only be semi-aquatic (e.g., Alligator mississippiensis, Hippopotamus amphibius, Rana aurora).

Using Google Scholar48 and Scopus49, for each species and subspecies, we searched for papers that included “[scientific name]” OR “[common name]” AND “sound” OR “call” OR “acoustic” OR “vocal” OR “noise” in the title or keywords. We confirmed that papers within the search list referred to underwater sound production of the species in question and evaluated the content using the categories of sound production detailed in Table 1. For each species and subspecies, when applicable, the oldest reference that identified sound production under natural conditions was provided as the source of information for the WoRMS database. On occasion, a later source was retained, instead, if it had more information on the repertoire or behavior of the species than the oldest reference. Papers that provided information on an alternative or additional species outside of the list produced from WoRMS were retained for our dataset and added to the WoRMS database.

There has been no formal assessment (e.g., evolutionary analysis) of the likelihood of underwater sound production for these taxa. Additionally, for these taxa, few studies have been conducted where researchers have attempted to elicit underwater sound production. Therefore, for species that did not have a report of underwater sound production testing, the following actions were taken. If multiple species within the same family were found to produce sound, the species in question was deemed likely to produce sound under natural conditions. For example, most pinnipeds have reports of underwater sound production, but not all, and those that do not have associated reports have not been fully investigated for this behavior. As such, it was deemed likely that all pinniped species produce sound underwater, which can be confirmed when further investigations take place. Similarly, while few penguins reportedly exhibit this trait, the ones that have been studied have produced active sound underwater. Thus, all penguin species without an associated report have currently been assigned to Category 3, as well. For taxa where studies and reports of sound production are few (e.g., crocodilians, mustelids, rodents), species that did not have an associated report of sound production were assigned to Category 1 (i.e., unknown or unconfirmed).

Fishes

For the purposes of this dataset, fishes were defined as any extant, accepted species (not only marine) in the Subphylum Vertebrata, except for any species in the Megaclass Tetrapoda, as listed on WoRMS38. This includes the taxa Agnatha, Chondrichthyes, Sarcopterygii, and Actinopterygii. A complete list of fish species for use in the data collection was downloaded from WoRMS using either the WoRMS website or the R packages taxize50 and worms51.

The categorizations for fishes were adapted from two existing data sources: FishSounds5,34,52 and Rice et al.53. Both data sources used different criteria from the sonifery categories defined for WoRMS to determine the likelihood of sonifery in fishes. Nonetheless, they represent comprehensive resources of scientific knowledge about soniferous fish diversity and therefore allowed us to circumvent the need to re-review the full scope of literature on sound production in fishes, which comprise roughly 35,000 extant species54 and over 1,000 species that have been studied for sound production across more than 800 publications55.

The FishSounds website (available at FishSounds.net) presents a global inventory of fish species examined for sound production in the scientific literature. For each species studied in each reference, FishSounds reports whether the species has been found to produce sound, the sound production type as active and/or passive (as defined in Table 2), the varying methodologies used to examine the species for sound production, and the possibility for uncertainty (see Looby et al.5 for a complete description of the methods). The FishSounds dataset is therefore different in its sonifery determinations than the WoRMS categorizations described herein, but it provided an effective starting point for our data collection. The FishSounds dataset was retrieved from the FishSounds permanent data repository52. As the FishSounds dataset uses FishBase as its taxonomic source54,56, the species in the FishSounds dataset were matched to their respective accepted species entries on WoRMS using its Match Taxa tool38.

Using the FishSounds dataset, species were re-assigned to different WoRMS categories either automatedly or following a re-review process. If a species had been examined morphophysiologically or auditorily for sound production as defined by Looby et al.5 and found to be soniferous but with some amount of doubt in the authors’ conclusions or without visual confirmation of an auditory examination, then the species was placed in Category 3 and the FishSounds dataset was cited. To place fishes into Categories 4, 5, and 6 (Table 1), the FishSounds dataset was filtered to produce a list of species and their associated references that had examined the fish species for sound production auditorily with visual confirmation and had found the species to produce active and/or passive sounds, without doubt or uncertainty associated with their species identification, whether sounds were produced, nor the type of sound produced—all as determined following Looby et al.5 The references in the resulting list were then reviewed to determine whether the fish species produced the reported sounds under natural conditions. A total of 819 species studied across 613 references were assessed this way.

For the species that needed to be re-reviewed, if sound production was reported as naturally occurring in at least one reference in the FishSounds dataset, those species were placed in the appropriate Category 4, 5, or 6, depending on the types of sounds produced as reported in the references. If not, they were placed in Category 3. Because of the widespread use of direct manipulation to elicit fish sound production in the scientific literature across time and taxa42,43,44,57,58,59,60,61,62, authors within each reference had to explicitly specify that sound production occurred without direct human manipulation to be considered natural. One or two references that documented sound production were provided for each of the species that were reviewed with the methods described in this and the previous paragraph. Not all references that studied a particular fish species for sound production were reviewed in this data collection effort, as in some cases a single reference was sufficient to determine a species belonged in Category 4, 5, or 6. Additionally, the references cited for each category are not necessarily the oldest or most comprehensive descriptors of sound production behaviors—they may have just been the first reviewed that reported natural sound production. We recommend viewing the original FishSounds dataset for a more detailed overview of the sound production studies conducted for each species52.

Rice et al.53 conducted an ancestral state reconstruction analysis of sound production in Actinopterygii based on family-level sonifery data taken from the literature. Determinations made by Rice et al.53 of ancestral-state sonifery at the family level were extracted from their Supplemental Figure S1. The families were then used to determine whether species were likely to be soniferous (Category 3) or not likely to be soniferous (Category 2) based on these taxonomic relationships, for any species not covered by the FishSounds dataset. Such categorizations cited the Rice et al.53 publication as their determining source.

Species that were not included in the Rice et al.53 dataset and were examined but not found to produce sound in the FishSounds dataset were placed in Category 2 and the FishSounds dataset was cited. While it is generally assumed that all fish species are capable of making passive sound under certain conditions13, we did not include such an assumption in our categorizations as it remains unclear whether all fishes are likely to produce passive sounds naturally. Species that were not included in either dataset were placed in Category 1 and the FishSounds dataset was cited. Any fish species not listed in the provided dataset should be considered Category 1, as they were either absent from WoRMS, not listed as accepted species on WoRMS at the time of the review, or not covered under the definition of a fish species listed above.

Invertebrates

Since invertebrate species are so numerous with few that have been studied for their sound production, we only included species in our dataset for which we could find relevant publications. Any other species not listed in the dataset should be considered in Category 1 (unknown or undetermined) until further data can be collected or additional research is done.

We conducted both targeted and haphazard searches to compile data on invertebrate underwater sound production. We focused on several taxonomic groups that are more well-studied for their sound production. For crustaceans, we used the Web of Science Core Collection database47 and searched using the string: “TS = (crustacean*) AND ((TS = ((sound* OR noise* OR *acoustic* OR vocal*) NEAR/2 (mak* OR made OR produc* OR emit* OR communicat* OR call*))) OR (TS = (soniferous)))” following Looby et al.5 For mollusks, we searched by each class and group within the phylum (e.g., cephalopods) in Google Scholar using “[class name]” OR “[group name]” AND “sound” OR “call” OR “acoustic” OR “vocal” OR “soniferous”. We also searched haphazardly in Web of Science47, Google Scholar48, and personal reference libraries for any other reports of underwater sound production in these or other invertebrate taxa. Each publication found was read to determine its applicability to the data collection. The species studied were matched to their associated listing on WoRMS38 and placed in their appropriate categories accordingly.

Data Records

The known sonifery data are available in the figshare data repository in a single Excel spreadsheet file63. The spreadsheet contains three tabs: a data dictionary, the reference information, and the sonifery information. The data dictionary provides information defining each column variable present in the other two spreadsheet tabs, including the variable name, allowed values, variable definition, and any needed additional information. The reference information provides the citation information (e.g., authors, publication name) for all the references used to categorize species by known underwater sonifery. The DOIs of the associated references were also provided whenever available to aid in locating the references. The sonifery information contains the taxon names, the soniferous categories assigned to them, and any notes that were included about the categorizations. To relate which reference was cited for each soniferous trait record, the reference information can be linked to the sonifery information through the provided Reference Aphia IDs. The reference IDs were kept consistent with the Aphia ID system utilized by WoRMS but can also be considered independently from WoRMS if using this dataset as a stand-alone source. As scientific names may change with future taxonomic reclassifications, to improve dataset sustainability, for each taxon, we also provided the Taxon Aphia ID as listed in WoRMS, though this may be ancillary or unnecessary to the dataset’s use. The dataset as provided on figshare has also been integrated into WoRMS, where it can be more readily updated with new soniferous information or taxonomic reclassifications. Any R code and associated data files used to generate or summarize the dataset are also provided in figshare63.

Technical Validation

Data were collected by experts in their respective soniferous taxa using either existing data sources or through novel searches of the existing literature using systematized review methodology when possible64. The data collected were verified against other similar reviews65 or estimations of known soniferous species numbers66,67,68 when available to ensure the results provided herein were reasonable. Most of the data collected for the different animal groups identified in the methods were categorized by a single reviewer each, however, with limited external validation at the time of publishing. This may have introduced omissions or mistakes in the dataset based on human error or biases associated with the review methods. The WoRMS database allows for continual editing and so the authors, as WoRMS thematic experts, will continue to update and validate the data as new information becomes available or any corrections are needed. Any users of the compiled dataset should be aware of the possibility of errors and ongoing changes. Users are encouraged to verify any specific reports of sonifery using the references provided and to contact the authors of this data publication if any discrepancies are found.

As both active and passive sounds have potential ecological signaling and monitoring applications5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, the dataset attempted to capture both types of sonifery in its categories. The definitions provided for these sound types in Table 2 were adapted from previously published text and commonly used delineations in the scientific literature that the dataset was meant to encompass5,12,13,31,44,. The distinction between passive and active sounds, however, may exist more along a spectrum as opposed to in stark contrasts5. For example, active sound production may be the result of exaptation in taxa where it is not an ancestral trait69, and passive sounds may be associated with particular behaviors or situations5,70. Determining the use of sounds for intentional communication can often be uncertain and may require further behavioral testing to designate conclusively5,71,72,73. The dataset’s categorizations also relied on reviewers’ interpretations of sound production descriptions in the surveyed references. This process may have simplified more nuanced sonifery descriptions in the source materials. Users are therefore highly encouraged to refer to the provided data sources for additional information on the context surrounding the documented sound production. Because likely many species are capable of passive sound production in certain contexts (e.g., through swimming), species were only categorized as passively soniferous in the dataset if their sounds were detectable in a natural context within a scientific study. We also did not include reports of passive sounds for the tetrapods in our data collection, though there are likely many species that produce them31,71.

Users should be aware of potential limitations or qualifications associated with our categorizations. While our trait and category definitions relied on widely used and established differentiations in the sound production literature, they were relatively conservative in their inclusion of species in Categories 4, 5, and 6 and may therefore have led to the exclusion of species that are indeed naturally soniferous. For example, for the purposes of our data collection, we emphasized species that were shown to produce sounds underwater naturally without contact, electricity, tethering, or other forms of direct manipulation by humans, while still including sounds spontaneously produced in artificial environments (e.g., tanks). This may have led to the exclusion of species that do indeed produce sounds naturally, such as species who may make distress sounds in response to being caught by predators or those that readily produce sounds when handled but may have simply not yet been shown to do so in other agonistic situations7,43,59,74,75,76. Due to frequent uncertainty in studies of underwater sound production5, species may have been similarly excluded from Categories 4, 5, or 6 if their potential sonifery could not be confirmed in the surveyed studies. Additionally, for some taxa, we relied on ancestral state reconstruction analyses or assumptions of sonifery based on taxonomic relationships to determine species likely to be soniferous. There is, nonetheless, the possibility for sound production behaviors to be secondarily lost, thus the species deemed likely soniferous should be treated with caution53,77,78,79,80. Users should be aware of the assumptions and simplifications made by our categorizations, the potential for our understanding of sound production and likely sound production to change, and that the data may later be updated to reflect new research even if the categories themselves may not change.

Usage Notes

We envision numerous possible applications for the dataset described herein to study sound production and other topics related to aquatic and semi-aquatic species worldwide. By listing a soniferous behavior trait on WoRMS, researchers will be able to easily search for and access known sonifery information for any species encompassed by our review. This will aid in identifying both known soniferous species and species lacking documented sound production. In addition to being listed on WoRMS, the soniferous trait data associated with this review is available in a spreadsheet file in figshare that may be easier to use in analyses. The ecological trait data can be easily integrated with other information available on WoRMS itself (e.g., taxonomy, environment) or its associated databases (e.g., conservation status, distribution, invasive status) to study global patterns of sound production behavior and the use of passive acoustics for ecological monitoring. Sonifery has been studied in these contexts before, but only with more limited datasets5,53,65. Researchers interested in conducting such analyses should be aware of the availability of software packages that could be used to easily access related datasets (e.g., the rfishbase56, taxize50, worms51, and rinat81 packages in R). We hope our data will facilitate future research on the distribution, evolution, ecology, management, and conservation of underwater soniferous species worldwide.

Code availability

Code and associated data files are available in the figshare data repository63.

References

Ladich, F. Acoustic communication and the evolution of hearing in fishes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1285–1288, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2000.0685 (2000).

Ladich, F. & Winkler, H. Acoustic communication in terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 2306–2317, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.132944 (2017).

Given, M. F. Does physical or acoustical disturbance cause male pickerel frogs, Rana palustris, to vocalize underwater? Amphib.-Reptil. 29, 177–184, https://brill.com/view/journals/amre/29/2/article-p177_4.xml?language=en (2008).

Stanley, J. A., Radford, C. A. & Jeffs, A. G. Location, location, location: finding a suitable home among the noise. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3622–3631, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0697 (2012).

Looby, A. et al. A quantitative inventory of global soniferous fish diversity. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 32, 581–595, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09702-1 (2022).

Bouwma, P. E. & Herrnkind, W. F. Sound production in Caribbean spiny lobster Panulirus argus and its role in escape during predatory attack by Octopus briareus. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 43, 3–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330909509977 (2009).

Guerra, A. et al. A new noise detected in the ocean. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 87, 1255–1256, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315407058225 (2007).

Goto, R., Hirabayashi, I. & Palmer, A. R. Remarkably loud snaps during mouth-fighting by a sponge-dwelling worm. Curr. Biol. 29, R617–R618, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.047 (2019).

Staniewicz, A., Foggett, S., McCabe, G. & Holderied, M. Courtship and underwater communication in the Sunda gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii). Bioacoustics 31, 435–449, https://doi.org/10.1080/09524622.2021.1967782 (2022).

Landrau‐giovannetti, N., Mignucci‐giannoni, A. A. & Reidenberg, J. S. Acoustical and anatomical determination of sound production and transmission in West Indian (Trichechus manatus) and Amazonian (T. inunguis) manatees. Anat. Rec. 297, 1896–1907, https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.22993 (2014).

Staaterman, E., Paris, C. B. & Kough, A. S. First evidence of fish larvae producing sounds. Biol. Lett. 10, 20140643, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.0643 (2014).

Kasumyan, A. O. Acoustic signaling in fish. J. Ichthyol. 49, 963–1020, https://doi.org/10.1134/S0032945209110010 (2009).

Kasumyan, A. O. Sounds and sound production in fishes. J. Ichthyol. 48, 981–1030 (2008).

Lillis, A., Eggleston, D. B. & Bohnenstiehl, D. R. Oyster larvae settle in response to habitat-associated underwater sounds. PLOS ONE 8, e79337, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079337 (2013).

Banner, A. Use of sound in predation by young lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris (Poey). Bull. Mar. Sci. 22, 251–283, https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/umrsmas/bullmar/1972/00000022/00000002/art00001# (1972).

Ladich, F. Shut up or shout loudly: predation threat and sound production in fishes. Fish Fish. 23, 227–238, https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12612 (2022).

Remage-Healey, L., Nowacek, D. P. & Bass, A. H. Dolphin foraging sounds suppress calling and elevate stress hormone levels in a prey species, the Gulf toadfish. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 4444–4451, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.02525 (2006).

Flood, A. S., Goeritz, M. L. & Radford, C. A. Sound production and associated behaviours in the New Zealand paddle crab Ovalipes catharus. Mar. Biol. 166, 162, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-019-3598-x (2019).

McIver, E. L., Marchaterre, M. A., Rice, A. N. & Bass, A. H. Novel underwater soundscape: acoustic repertoire of plainfin midshipman fish. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 2377–2389, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.102772 (2014).

Schärer-Umpierre, M. T. et al. The purr of the lionfish: sound and behavioral context of wild lionfish in the Greater Caribbean. Gulf Caribb. Res. 30, GCFI15–GCFI19, https://doi.org/10.18785/gcr.3001.17 (2019).

Rountree, R. A. & Juanes, F. Potential of passive acoustic recording for monitoring invasive species: freshwater drum invasion of the Hudson River via the New York canal system. Biol. Invasions 19, 2075–2088, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1419-z (2017).

Walters, S., Lowerre-Barbieri, S., Bickford, J. & Mann, D. Using a passive acoustic survey to identify spotted seatrout spawning sites and associated habitat in Tampa Bay, Florida. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 138, 88–98, https://doi.org/10.1577/T07-106.1 (2009).

Brunoldi, M. et al. A permanent automated real-time passive acoustic monitoring system for bottlenose dolphin conservation in the Mediterranean Sea. PLOS ONE 11, e0145362, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145362 (2016).

Fournet, M. E. H., Stabenau, E. & Rice, A. N. Relationship between salinity and sonic fish advertisement behavior in a managed sub-tropical estuary: making the case for an acoustic indicator species. Ecol. Indic. 106, 105531, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105531 (2019).

Mallekh, R., Lagardère, J. P., Eneau, J. P. & Cloutour, C. An acoustic detector of turbot feeding activity. Aquaculture 221, 481–489, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(03)00074-7 (2003).

Duarte, C. M. et al. The soundscape of the Anthropocene ocean. Science 371, eaba4658, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba4658 (2021).

Cox, K., Brennan, L. P., Gerwing, T. G., Dudas, S. E. & Juanes, F. Sound the alarm: a meta‐analysis on the effect of aquatic noise on fish behavior and physiology. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 3105–3116, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14106 (2018).

Butler, J., Stanley, J. A. & Butler, M. J. Underwater soundscapes in near-shore tropical habitats and the effects of environmental degradation and habitat restoration. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 479, 89–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2016.03.006 (2016).

Gordon, T. A. C. et al. Habitat degradation negatively affects auditory settlement behavior of coral reef fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5193–5198, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719291115 (2018).

Coquereau, L., Lossent, J., Grall, J. & Chauvaud, L. Marine soundscape shaped by fishing activity. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160606, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160606 (2017).

Frankel, A. S. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals Third Edition (eds. Würsig, B., Thewissen, J. G. M. & Kovacs, K. M.) Sound, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00235-1 (Academic Press, 2018).

van der Lee, G. H., Desjonquères, C., Sueur, J., Kraak, M. H. S. & Verdonschot, P. F. M. Freshwater ecoacoustics: listening to the ecological status of multi-stressed lowland waters. Ecol. Indic. 113, 106252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106252 (2020).

Solé, M. et al. Marine invertebrates and noise. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1129057, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1129057 (2023).

Looby, A. et al. FishSounds Version 1.0: a website for the compilation of fish sound production information and recordings. Ecol. Inform. 74, 101953, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101953 (2023).

Parsons, M. J. G. et al. Sounding the call for a global library of underwater biological sounds. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 810156, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.810156 (2022).

Costello, M. J. et al. Biological and ecological traits of marine species. PeerJ 3, e1201, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1201 (2015).

Costello, M. J. et al. Global coordination and standardisation in marine biodiversity through the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) and related databases. PLOS ONE 8, e51629, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051629 (2013).

WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), https://www.marinespecies.org (2023).

Flanders Marine Institute. WoRMS in literature. World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), https://www.marinespecies.org/wormsliterature.php (2023).

Flanders Marine Institute. UN Decade for Ocean Sciences. World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), https://www.marinespecies.org/about.php#oceandecade (2023).

Joy, J. B., Liang, R. H., McCloskey, R. M., Nguyen, T. & Poon, A. F. Y. Ancestral reconstruction. PLOS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004763, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004763 (2016).

Abbott, C. C. Traces of a voice in fishes. Am. Nat. 11, 147–156, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2448098.pdf (1877).

Morgan, L. D. & Fine, M. L. Agonistic behavior in juvenile blue catfish Ictalurus furcatus. J. Ethol. 38, 29–40, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-019-00621-6 (2020).

Fish, M. P. & Mowbray, W. H. Sounds of Western North Atlantic fishes, a reference file of biological underwater sounds (The Johns Hopkins Press, 1970).

Erbe, C. et al. Review of underwater and in-air sounds emitted by Australian and Antarctic marine mammals. Acoust. Aust. 45, 179–241, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40857-017-0101-z (2017).

Committee on Taxonomy. List of marine mammal species and subspecies. The Society of Marine Mammalogy, https://marinemammalscience.org/science-and-publications/list-marine-mammal-species-subspecies/ (2022).

Clarivate. Web of Science, https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search (2023).

Google. Google Scholar, https://scholar.google.com/schhp?hl=en (2023).

Elsevier B. V. Scopus, https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic&zone=header&origin=recordpage#basic (2023).

Chamberlain, S. A. & Szöcs, E. taxize: taxonomic search and retrieval in R. F1000Research 2, 191, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-191.v2 (2013).

Holstein, J. worms: World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) Client https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/worrms/index.html (2020).

Looby, A. et al. FishSounds website data repository, V4. Borealis https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/TACOUX (2021).

Rice, A. N. et al. Evolutionary patterns in sound production across fishes. Ichthyol. Herpetol. 110, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1643/i2020172 (2022).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase Version 02/2023 http://www.fishbase.org/search.php (2023).

Looby, A. et al. FishSounds Version 2, https://fishsounds.net/ (2023).

Boettiger, C., Lang, D. T. & Wainwright, P. C. rfishbase: exploring, manipulating and visualizing FishBase data from R. J. Fish Biol. 81, 2030–2039, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03464.x (2012).

Burkenroad, M. D. Notes on the sound-producing marine fishes of Louisiana. Copeia 1931, 20–28, https://doi.org/10.2307/1436789 (1931).

Iwatani, H., Onuki, A. & Somiya, H. Sound production in fourspine sculpin Cottus kazika, Cottidae: sound properties and seasonal variations of sonic muscle size. Suisan Zoshoku 59, 343–350, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/aquaculturesci/59/3/59_343/_pdf/-char/ja (2011).

Knight, L. & Ladich, F. Distress sounds of thorny catfishes emitted underwater and in air: characteristics and potential significance. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 4068–4078, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.110957 (2014).

Uno, M. & Konagaya, T. Studies on the swimming noise of the fish. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 26, 1069–1073, https://doi.org/10.2307/1538923 (1960).

Parmentier, E., Boyle, K. S., Berten, L., Brié, C. & Lecchini, D. Sound production and mechanism in Heniochus chrysostomus (Chaetodontidae). J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2702–2708, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.056903 (2011).

Bessey, C. & Heithaus, M. R. Alarm call production and temporal variation in predator encounter rates for a facultative teleost grazer in a relatively pristine seagrass ecosystem. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 449, 135–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2013.09.008 (2013).

Looby, A. et al. The inclusion of underwater sonifery within the World Register of Marine Species, figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6704481.v1 (2023).

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26, 91–108, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x (2009).

Rountree, R. A., Bolgan, M. & Juanes, F. How can we understand freshwater soundscapes without fish sound descriptions? Fisheries 44, 137–143, https://doi.org/10.1002/fsh.10190 (2019).

Kaatz, I. M. & Stewart, D. S. Acoustically innovative, lineages: the distribution of sound producing mechanisms among teleost fishes. Am. Zool. 39, 16A (1999).

Kaatz, I. M. Multiple sound-producing mechanisms in teleost fishes and hypotheses regarding their behavioural significance. Bioacoustics 12, 230–233, https://doi.org/10.1080/09524622.2002.9753705 (2002).

Rountree, R. et al. Listening to fish: applications of passive acoustics to fisheries science. Fisheries 31, 433–446, https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446(2006)31[433:LTF]2.0.CO;2 (2006).

Parmentier, E., Diogo, R. & Fine, M. L. Multiple exaptations leading to fish sound production. Fish Fish. 18, 958–966, https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12217 (2017).

Straight, C. A., Freeman, B. J. & Freeman, M. C. Passive acoustic monitoring to detect spawning in large-bodied catostomids. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 143, 595–605, https://doi.org/10.1080/00028487.2014.880737 (2014).

Van Opzeeland, I. C., Corkeron, P. J., Leyssen, T., Similä, T. & Van Parijs, S. M. Acoustic behaviour of Norwegian killer whales, Orcinus orca, during carousel and seiner foraging on spring-spawning herring. Aquat. Mamm. 31, 110–119, https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.31.1.2005.110 (2005).

Buscaino, G., Ceraulo, M., Canale, D. E., Papale, E. & Marrone, F. First evidence of underwater sounds emitted by the living fossils Lepidurus lubbocki and Triops cancriformis (Branchiopoda: Notostraca). Aquat. Biol. 30, 101–112, https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00744 (2021).

Rountree, R. A., Juanes, F. & Bolgan, M. Air movement sound production by alewife, white sucker, and four salmonid fishes suggests the phenomenon is widespread among freshwater fishes. PLOS ONE 13, e0204247, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204247 (2018).

Fine, M. L. et al. Conservation, Ecology, and Management of Catfish: the Second International Symposium (eds. Michaletz, P. H., Vincent H. & Travnichek, V. H.) A primer on functional morphology and behavioral ecology of the pectoral spine of the channel catfish, https://doi.org/10.47886/9781934874257.ch63 (American Fisheries Society, 2011).

Bosher, B. T., Newton, S. H. & Fine, M. L. The spines of the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, as an anti-predator adaptation: an experimental study. Ethology 112, 188–195, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01146.x (2006).

Parmentier, E. et al. Simultaneous production of two kinds of sounds in relation with sonic mechanism in the boxfish Ostracion meleagris and O. cubicus. Sci. Rep. 9, 4962, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41198-x (2019).

Gkenas, C., Malavasi, S., Georgalas, V., Leonardos, I. D. & Torricelli, P. The reproductive behavior of Economidichthys pygmaeus: secondary loss of sound production within the sand goby group? Environ. Biol. Fishes 87, 299–307, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-010-9597-x (2010).

Gerald, J. W. Sound production during courtship in six species of sunfish (Centrarchidae). Evolution 25, 75–87, https://doi.org/10.2307/2406500 (1971).

Pisanski, K., Marsh-Rollo, S. E. & Balshine, S. Courting and fighting quietly: a lack of acoustic signals in a cooperative Tanganyikan cichlid fish. Hydrobiologia 748, 87–97, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-1933-2 (2015).

Spinks, R. K., Muschick, M., Salzburger, W. & Gante, H. F. Singing above the chorus: cooperative Princess cichlid fish (Neolamprologus pulcher) has high pitch. Hydrobiologia 791, 115–125, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-016-2921-5 (2017).

Barve, V., Hart, E. & Guillou, S. rinat: access ‘iNaturalist’ data through APIs https://cloud.r-project.org/web/packages/rinat/index.html (2022).

Acknowledgements

The conception of this project originated within the working group for a Global Library of Underwater Biological Sounds (GLUBS), which includes a number of the co-authors of this dataset. The GLUBS working group is supported by the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research, Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute, and Rockefeller Program for the Human Environment. We thank them for their initiative and support. The Richard Lounsbery Foundation has provided financial support for the continued development of this working group. Thank you to the WoRMS Editorial Board and WoRMS Data Management Team, especially Leen Vandepitte and Stefanie Dekeyzer, for allowing the inclusion of sonifery as a WoRMS trait and for their assistance in data definition and integration with WoRMS. Thank you also to Edward Urban for his assistance with the WoRMS trait and category definitions. This work makes use of data and infrastructure provided by VLIZ and funded by Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO) as part of the Belgian contribution to LifeWatch. The work of the WoRMS Data Management Team is funded by FWO as part of the Belgian contribution to LifeWatch.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.G.P. first conceived of the project. M.J.G.P. and A.L. coordinated with WoRMS. A.L., L.D.I., C.E., T.A.M., M.J.G.P., C.R., A.N.R. and J.S. drafted the data categorizations, with additional input from the other authors. C.E. led the categorization of marine mammals. M.J.G.P. led the categorization of the other tetrapods. A.L. and A.N.R. led the categorization of fishes with input from S.B., K.C., H.L.D., F.J., C.W.M., L.K.R., A.R., R.R., B.S. and S.V. L.D.I., T.A.M., Y.J., C.R. and J.S. led the categorization of invertebrates. A.L. wrote the first outline of the manuscript. All authors contributed to subsequent manuscript drafts and provided editorial feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Looby, A., Erbe, C., Bravo, S. et al. Global inventory of species categorized by known underwater sonifery. Sci Data 10, 892 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02745-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02745-4