Abstract

Metadata from epidemiological studies, including chronic disease outcome metadata (CDOM), are important to be findable to allow interpretability and reusability. We propose a comprehensive metadata schema and used it to assess public availability and findability of CDOM from German population-based observational studies participating in the consortium National Research Data Infrastructure for Personal Health Data (NFDI4Health). Additionally, principal investigators from the included studies completed a checklist evaluating consistency with FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, Reusability) within their studies. Overall, six of sixteen studies had complete publicly available CDOM. The most frequent CDOM source was scientific publications and the most frequently missing metadata were availability of codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Principal investigators’ main perceived barriers for consistency with FAIR principles were limited human and financial resources. Our results reveal that CDOM from German population-based studies have incomplete availability and limited findability. There is a need to make CDOM publicly available in searchable platforms or metadata catalogues to improve their FAIRness, which requires human and financial resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous epidemiological studies have been examining risk factors of chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, which represent a high burden of disease globally1,2. In Germany, where these three disease groups account for 44% of the total disability-adjusted life years (19.5%, 18.8%, 5.8% for cancer, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, respectively in 2019)3, several population-based observational studies are dedicated to the study of risk factors of chronic diseases. The potential of research data derived by these studies to improve our understanding of health and disease can be substantially enhanced by following the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, Reusability), optimizing interpretability and reproducibility of results, as well as reuse of data4. While it is increasingly accepted that all research data should follow the FAIR principles, implementation is not ubiquitous and interoperability across data sources is still limited5,6. In Germany, the consortium National Research Data Infrastructure for Personal Health Data (NFDI4Health, https://www.nfdi4health.de/en/) - with the participation of 26 observational studies – seeks to increase the value of research in epidemiology, public health, and clinical trial-based medicine, by making high quality personal health research data from Germany internationally accessible according to the FAIR principles7.

Research data in population-based observational studies usually refers to the sum of data that characterize each participant in that study, or parts thereof (i.e., personal data, unless anonymized). However, an important step in achieving FAIR data is the availability of rich metadata describing these research data8. The assessment of chronic diseases in observational studies is challenging, and each disease can be assessed in many different ways. Thus, the methods used to assess diseases differ between studies, depending on study aims, design, study population, and resources available9. In the case of chronic diseases, metadata include, among others, information on whether the outcome is prevalent or incident, on disease subtypes assessed and classification system(s) used, how data were collected (i.e., questionnaires, interviews, study examinations, administrative databases, or through a combination of sources), and whether and how self-reported diseases were verified (i.e., confirmed on a case basis) or validated (i.e., plausibility of prevalence or incidence observed in a study population evaluated based on a reference population)10.

Differences in assessment methods used have implications on how the data can be reused and how they should be interpreted. Knowledge of how data are collected is not only important for the scientific community to gain awareness of contextual constraints impacting interpretation, but also to enable reuse of data, for example in meta-analyses or pooled analyses. However, details on chronic disease assessment methods – hereafter referred to as chronic disease outcome metadata (CDOM) – are often difficult to find. Therefore, there is a need for specific reporting guidelines using a common metadata schema capturing the vast characteristics of chronic disease assessment and ascertainment methods used in epidemiological studies.

This study proposes a schema for CDOM in epidemiological studies and applies it to population-based observational studies in Germany, describing the current status of CDOM public availability and findability. Additionally, it assesses perceived consistency of CDOM with FAIR principles within identified studies.

Results

Summary of included studies

Sixteen observational studies participating in NFDI4Health collected chronic disease data (i.e., data on cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus). Of these, most studies had a cohort design (n = 13, with sample size ranging from 1,779 to ~205,000 participants), one was a cross-sectional study (7,124 participants), one had a mixed design with both cross-sectional and cohort characteristics (sample size of 8,152 participants), and one study comprised of multiple cross-sectional surveys (four samples ranging from 19,294 to 24,016 participants). An overview of the included studies is shown in Table 1. CDOM for these studies were searched according to the search strategy and criteria described in the methods section and in Supplementary Table 1.

Publication of chronic disease outcome metadata: evaluation based on proposed schema

A metadata schema with all relevant CDOM was developed within NFDI4Health (see Table 2). CDOM were evaluated in each study per source and outcome and considered to be complete when information about all CDOM fields was available (metadata sources and metadata completeness evaluation scheme described in Tables 3, 4, respectively). For this, an in-depth search within the identified sources of metadata was performed and the identified metadata was recorded in detail by source and metadata field in Supplementary Table 2. This information was then used to summarize our findings in Tables 5, 6, described in the following results subsections. More details are provided in the methods section. Out of the sixteen included studies, publicly available CDOM were complete for all outcomes for 6 studies (CARLA, GEDA, NAKO, KORA, lidA, SHIP/SHIP Trend), complete for some outcomes for 4 studies (EPIC-Heidelberg, EPIC-Potsdam, GHS, IDEFICS/I.Family), and partial for the remaining 6 studies. Table 5 shows the overall status of publicly available CDOM in each study.

Public availability by source

Overall, scientific publications were the most frequent source of publicly available CDOM (n = 16), followed by study websites (n = 15; excluding links and references), study/trial registry databases (n = 11; excluding links and references), and data documentation (n = 10) (Fig. 1). Among the six studies with complete publicly available outcome metadata, the main sources of CDOM were scientific publications (GEDA, NAKO, SHIP/SHIP-Trend) and complementary information obtained both through scientific publications and data documentation (CARLA, KORA, lidA) (Table 5). Eleven studies had a (meta-)data access infrastructure. Of these, seven offered access without registration, three allowed registration by allowing users to sign up or to send a request per email, and one had no registration option (Fig. 2).

Proportion and number of included studies with available and accessible (meta-)data infrastructure (total n = 16). Study-specific internet-accessible portals (through which data documents are often accessible) were considered as (meta-)data infrastructure. Available if the existence of a (meta-)data infrastructure was identified through the study website and/or data document search; accessible if contents could be viewed without registration or registration. (a) Credentials needed, no registration option. (b) Corresponding to (meta-)data access infrastructure not available.

Public availability by metadata field

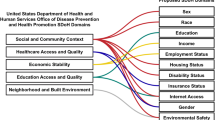

All publicly available CDOM found was recorded in detail in Supplementary Table 2. Table 6 summarizes this information and rates completeness of CDOM to examine what kind of outcome metadata are more often publicly available or more often missing. A score was applied within each study to evaluate public availability of each metadata field (see evaluation scheme in Table 4: “3”, complete for all outcomes; “2”, complete for some outcomes; “1”, partial; “0“, missing/no metadata). Based on these scores, ICD-10 code was the field that was more often missing, with a median score of 2. All other metadata fields were more often publicly available, with a median score of 3. Similarly, Fig. 3 reflects the lower availability of information on whether codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) were used, followed by the fields self-report: reference period and self-report: verification/validation. Conversely, data on prevalent/incident outcome and primary/secondary outcome show the highest proportion of completeness.

Proportion and number of included studies with complete, partial, and missing publicly available chronic disease outcome metadata, by metadata field (total n = 16). na, does not apply (not part of study design). Metadata considered complete if all aspects of the chronic disease outcome metadata schema (Table 2) are covered for all examined cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and cancers.

Perceived consistency with FAIR principles and perceived barriers

Principal investigators from ten out of the sixteen included studies (one principal investigator by study; N = 10 principal investigators) filled out a survey including the CDOM-adapted checklist of the criteria to meet the FAIR guiding principles (Supplementary Table 3) and shared their perceived main barriers for consistency with the FAIR principles. Principal investigators were prompted to answer always yes/no to each item Perceived consistency of CDOM with FAIR principles ranged from 40% to 70% for findability criteria, from 40% to 60% for accessibility criteria (items A1. and A2.), from 50% to 70% for interoperability criteria, and 60% for reusability criteria (item R1.) (Fig. 4). The main perceived barrier was limited human resources (80% very important barrier, 10% moderately important barrier, 10% not an important barrier), followed by limited financial resources (60% very important barrier, 30% moderately important barrier, 10% not an important barrier) (Fig. 5). Other barriers mentioned by principal investigators were related to unavailability of adequate of harmonization tools, organizational barriers, legal barriers, and limited data quality (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Based on the proposed CDOM schema, our findings reveal that CDOM from German observational studies are often not fully described in publicly available metadata sources. Among the sixteen included observational studies, six studies had complete publicly available CDOM. The main source of publicly available CDOM were scientific publications and the most frequently missing metadata were whether ICD-10 codes were available, followed by the reference period for the questions from self-reported outcomes and whether and how self-reported outcomes were verified and/or validated.

While CDOM seem to be only partly publicly available, the majority of studies had a (meta-)data access infrastructure accessible without registration, or registration was possible by requesting access. However, about a third of the included studies did not have such infrastructure or it was not publicly accessible. In such cases, data reuse is mostly limited to scientists within specific networks or to those who are already familiar with the studies in question. Rich CDOM that can be found by external parties would substantially assist the scientific community by increasing data interpretability and reusability and thus the value of data and the range of scientific questions on chronic disease risk and progression that could be addressed within and across existing observational studies. Having access to CDOM before the submission of an analysis request would also facilitate study selection and clarify harmonization needs (e.g., for pooled analysis of multiple studies)11. For example, knowing whether two studies used different disease classification systems could help the planning of the data harmonization process.

It may not be surprising that our findings suggest the richest source of publicly available CDOM is scientific publications, but it highlights a problem for findability: publications are the traditional way how scientists make research results publicly available. However, these publications usually focus on addressing scientific research questions, rather than on publishing metadata. Although some epidemiological journals also allow the publication of papers on study or cohort profiles12, the focus is usually on study design aspects and instruments, rather than on metadata. As a result, metadata are spread across separate documents, often only addressing the necessary information to make sense of the research question(s) addressed in the publication. While finding scientific publications – a time-consuming task that is dependent on search engine and search strategy – may be difficult, finding the metadata within the scientific publications poses another hurdle, as they are not indexed and searchable within the documents5. Ideally, CDOM (together with all study metadata) should be centralized (e.g., metadata catalogue on the study’s website) and accessible; and should be linked to publications, data repositories, and other sources of study metadata. By reducing the number of sources repeating the same information and instead linking to a central metadata catalogue or repository, there is a lower risk of inconsistencies (e.g., updating metadata in the primary source but forgetting secondary sources).

There are various reasons why CDOM are often not all publicly available and consistent with FAIR principles. While the concept of FAIR (meta-)data is fairly new8, the observational studies included in our evaluation date as far as the 1980s and implementing post hoc classifications of data elements to some standard is difficult and would require considerable resources (i.e., financial, human, and technical) that may not be available. This is in line with our observation that most principal investigators in our survey indicated that limited human resources were the main perceived barrier. Despite these difficulties, there is interest from both more recent, and longer existing German observational studies to improve consistency with the FAIR (meta-)data principles, reflected by their participation in consortia such as NFDI4Health7. As the efforts of the included studies to improve adherence to the FAIR principles are ongoing, the findings in this paper reflect the status of CDOM public availability at the time of publication.

Another obstacle for FAIR CDOM is the lack of guidelines or standards for CDOM reporting from observational studies. Our proposed CDOM schema outlines the relevant contextual information that should be included in CDOM reporting to improve interpretability and interoperability. Additionally, it is not clear how FAIRness of CDOM in observational studies should be evaluated. While other FAIR guiding prinples-based evaluation tools have been applied in other fields such as physics and education13,14,15,16, we considered the checklist we implemented – the FAIR guiding principles8 applied to CDOM – to be the most appropriate approach to evaluate the principal investigators’ perception of CDOM FAIRness in their respective observational studies. For this purpose, the breadth of the FAIR guiding principles can allow the principal investigators to consider different implementations of the FAIR principles in their studies. However, comments submitted with the surveys showed that some respondents still found some items difficult to evaluate in the context of CDOM in their study. Other scientists have also found the interpretation challenging and state that the principles should serve as guidelines rather than as standards5. Existing standards and classifications such as ICD-1017, SNOMED CT18, and MIABIS19 could be used to establish a specific vocabulary to report CDOM guided by the FAIR princpiles. As these standards and classifications were developed for use in a clinical or health care setting (biomedical research in the case of MIABIS) – although ICD-10 is frequently implemented in epidemiological research – they cover only some CDOM fields (e.g., disease classification in ICD-10, SNOMED-CT, some disease domains and reference periods asked for self-reported outcomes in SNOMED-CT, study examinations in SNOMED-CT and MIABIS). However, different standards and classifications may be used to complement each other and improve CDOM interoperability, for example, by using Unified Medical Language System (UMLS)20, which supports the use of multiple vocabularies. To achieve a standard approach, agreements on what standards to use for which metadata fields and on a standard CDOM-reporting template are warranted. Maelstrom Research (https://www.maelstrom-research.org/), which was developed to facilitate epidemiological research collaborations, developed a catalogue21 displaying some of the relevant metadata fields for chronic diseases (including ICD-10 disease group classifications); however, it remains mostly on study level metadata, missing outcome-specific metadata. The here proposed CDOM schema offers a blueprint for a more comprehensive metadata model. Resulting comparable contextual information across studies could then be integrated into a common framework such as the ISA-framework in metadata repositories (improved interoperability)22.

Our findings should be interpreted in consideration of the study’s strengths and limitations. While there are no guidelines for CDOM reporting in observational studies, we developed a metadata schema for chronic diseases within a large consortium with many participating large German observational studies. We also identify the status regarding public availability of CDOM among German observational studies, contributing knowledge that can be used to target gaps in CDOM findability and accessibility and improve external collaborations in the scientific community. Some limitations of our study include that public availability was conditional on finding the CDOM based on our search criteria; however, the risk of missing important publicly available CDOM was mitigated by requesting feedback from principal investigators about additional internet-available CDOM. Finally, we cannot generalize about the current status of public available CDOM across all observational studies, as all the studies included were from Germany and had already expressed an interest in FAIR data by joining the NFDI4Health consortium; however, most large observational studies conducted in Germany were included.

In summary, CDOM from many population-based observational studies in Germany are not completely publicly available. Those CDOM that are available stem mostly from scientific publications. As studies do not rely on single papers to publish CDOM, findability of these data is limited. There is a need to shift publicly available CDOM from scientific publications to publicly accessible platforms such as easily findable (e.g., visible on the study’s website and linked elsewhere) metadata catalogues (indexed and searchable), where centralization would support data management efforts and completeness of information. This shift requires the availability of the necessary resources for running these platforms, gathering of necessary information, as well as continuous management to keep this information up-to-date on the study level. Furthermore, guidelines or a common approach for how to achieve FAIR CDOM and how to make them publicly available is warranted; for example, a standardised approach to providing data dictionaries and how CDOM are displayed within them. Our findings provide valuable information for the German scientific community and may help justify and impulse efforts to make CDOM fully available in consolidated metadata platforms.

Methods

Study selection

This study was conducted within the framework of NFDI4Health. In 2018, the German ministry for education and research (BMBF) and state governments commissioned the German Research Foundation (DFG) to establish a National Research Data Infrastructure (NFDI); in 2019, the DFG launched a first call to form consortia that aim to improve management, accessibility, storage, and sustainability of scientific and research data in all areas of science23. NFDI4Health was one of the consortia that successfully applied to the first DFG call, and was selected to be funded for 5 years, starting in 202024. A total of 15 observational studies participated in the funding application for NFDI4Health (i.e., co-applicant studies). NFDI4Health initiated several community workshops to invite potential partners and users from the scientific community to participate in the consortium. Based on this activity, 11 additional observational studies have submitted letters of commitment to participate in the consortium (i.e., participating studies)24.

For the current analysis, we selected studies meeting the following inclusion criteria: 1) observational, population-based co-applicant or participating study in NFDI4Health; and 2) collecting information on cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Chronic disease outcome metadata (CDOM) schema

We developed a list of relevant contextual information about chronic disease outcomes for interpretation and reuse of data pertaining to the collection of chronic disease assessment-related information from observational, population-based studies participating in NFDI4Health. A final list of CDOM – a metadata schema specific to chronic disease ascertainment in epidemiological studies (Table 2) – includes general information about the outcome collected (i.e., prevalent or incident case, specific disease name/classification code, primary or secondary outcome) and the assessment method or data source (i.e., from self-report, from study examinations, from administrative databases), with additional levels of detail pertaining to the assessment method. Data pertaining to these metadata fields were searched for each of the eligible studies.

Sources of chronic disease outcome metadata (CDOM)

Based on an adaptation of previously defined sources contributing to (meta-)data discoverability25, the following sources were considered to provide CDOM from epidemiological studies: 1) scientific publications, 2) study websites, 3) study registry databases, and 4) data documents. Table 3 lists these sources in detail. Completeness of published CDOM for all eligible studies was evaluated based on screening of these four metadata sources. Databases used for searching scientific publications were PubMed and Google Scholar, without language restriction. All other sources of metadata were searched using Google including the following predefined keywords: study name, German city/region of the study, and other metadata-source describing keywords. Study/trial registries were searched additionally within websites of the following study registry databases: DRKS (German Clinical Trials Register, https://www.drks.de/), clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), ISRCTN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number, https://www.isrctn.com/), Maelstrom Research (https://www.maelstrom-research.org/), re3data.org (https://www.re3data.org/), ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, https://trialsearch.who.int/), euCanSHare (https://eucanshare.bsc.es/platform/), MDM Portal (https://medical-data-models.org/), and German Central Health Study Hub NFDI4Health (https://csh.nfdi4health.de/). Additionally, data documents were searched through the studies’ (meta-)data access infrastructure, if available. Different searches were carried out using terms in English and in German language between January and March 2022. The searches were repeated between August and September 2022 to include newly published CDOM. More details about the search criteria are described in Supplementary Table 1.

Evaluation of public availability of chronic disease outcome metadata (CDOM)

Public availability of CDOM was evaluated based only on publicly available information from the four aforementioned sources and was defined in terms of findability and accessibility. In a first step, metadata for all included studies were searched by screening in all the predefined metadata sources according to the search criteria detailed in Supplementary Table 1. To be publicly accessible, CDOM had to be both findable and freely accessible on the internet. Availability and accessibility of a (meta-)data access infrastructure was evaluated separately, for which we considered only internet-accessible portals. The existence of such portals was explored within the study website and the search for data documents. After recording all the identified publicly available CDOM by study, principal investigators from all included studies were invited to provide feedback on any missed publicly available CDOM. Any additional CDOM indicated by the principal investigators were added to the results as long as they were available online.

Evaluation of publicly available CDOM by study

Public availability of CDOM was evaluated overall for each study, and was considered to be complete if a detailed list of all the outcomes of interest that were collected in a study was publicly available and data on all the metadata fields listed in Table 2 was available for each corresponding chronic disease outcome. If data were complete for some outcomes only, published CDOM was considered to be complete for some outcomes. If only some of the outcome metadata fields could be filled for one or more chronic disease outcomes, published CDOM was considered to be partial. If no metadata fields could be filled based on publicly available information, published CDOM was considered to be missing. Table 4 details this evaluation scheme.

Evaluation of publicly available CDOM by metadata source and by metadata field

Publicly available CDOM was also recorded in more detail, distinguishing what kind of metadata were found in what source. Based on this information, we calculated a score summarizing public availability of CDOM across all included studies for each metadata field to examine what kind of outcome metadata are more often publicly available or more often missing. Separately for each study and source of metadata, the following rating scheme was used to evaluate each metadata field: “3”, complete for all outcomes; “2”, complete for some outcomes; “1”, partial; “0“, missing/no metadata (see Table 4). A score of 1 instead of 2 was given when some details about the metadata field were missing, e.g., if there was an indication that a study collected both prevalent as well as incident outcome data, but only a list of the prevalent outcomes was found (i.e., information about this metadata field was partial). This rating was applied to each outcome metadata field found in each metadata source. As the metadata sources study website and study/trial registries may serve both as direct sources (i.e., embedded metadata) and indirect sources (i.e., links and references), we evaluated them both as direct sources only and as direct plus indirect sources of metadata. For the overall rating, the highest metadata field score across metadata sources within each study made up the overall rating for a metadata field, which was then used to compute the median score per metadata field (range 0–3). For instance, if a study obtained a “3” for the metadata field “prevalent or incident outcome” based on data documents, but obtained a “2” based on the other metadata sources, the overall score for “prevalent or incident outcome” would be the highest score, i.e., “3” and it would be considered as complete for all outcomes.

Perceived consistency with FAIR principles by the Principal Investigators

Perceived consistency of CDOM with FAIR principles by the principal investigators was assessed based on the previously published criteria for each of the FAIR guiding principles8 with regard to CDOM (see Supplementary Table 3). These criteria were circulated as a checklist to the principal investigators of each of the included studies (one principal investigator representing one study), who returned the complete templates for their respective study (see Supplementary Fig. 1). For each criterion, principal investigators had the option of writing a comment, e.g., to express lack of clarity or to provide a more specific answer. Additionally, responders were also asked to provide feedback on their perceived barriers to achieve FAIR (meta-)data for their respective study. The following potential barriers were rated as “very important barrier”, “moderately important barrier” or “not an important barrier”: limited financial resources, limited human resources, limited technical resources, limited incentives. Additional barriers could be entered as free text and were rated in the same way.

Data availability

Data evaluated in this article consists of publicly available metadata; all relevant data are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Remington, P. L. & Brownson, R. C. Fifty years of progress in chronic disease epidemiology and control. MMWR Suppl 60, 70–77 (2011).

Brennan, P., Perola, M., van Ommen, G.-J., Riboli, E. & On behalf of the European Cohort, C. Chronic disease research in Europe and the need for integrated population cohorts. European Journal of Epidemiology 32, 741–749, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0315-2 (2017).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare Data Visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2020. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. (Accessed 19 February 2022).

Hasselbring, W., Carr, L., Hettrick, S., Packer, H. & Tiropanis, T. From FAIR research data toward FAIR and open research software. it - Information Technology 62, 39–47, https://doi.org/10.1515/itit-2019-0040 (2020).

Mons, B. et al. Cloudy, increasingly FAIR; revisiting the FAIR Data guiding principles for the European Open Science Cloud. Information Services & Use 37, 49–56, https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-170824 (2017).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. Interoperability and FAIRness through a novel combination of Web technologies. PeerJ Computer Science 3, e110, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.110 (2017).

Fluck, J. et al. NFDI4Health-Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur für personenbezogene Gesundheitsdaten [NFDI4Health- National Research Data Infrastructure for Personal Health Data]. Bausteine Forschungsdatenmanagement 2021, 72–85, https://doi.org/10.17192/bfdm.2021.2.8331 (2021).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3, 160018, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 (2016).

Smith, P. G., Morrow, R. H. & Ross, D. A. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Gordis, L. Epidemiology. Fourth edn, (Saunders Elsevier, 2009).

Pinart, M. et al. Joint Data Analysis in Nutritional Epidemiology: Identification of Observational Studies and Minimal Requirements. The Journal of Nutrition 148, 285–297, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxx037 (2018).

Oxford Academic. International Journal of Epidemiology: Information for Authors, https://academic.oup.com/ije/pages/general_instructions (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. A FAIR and AI-ready Higgs boson decay dataset. Scientific Data 9, 31, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01109-0 (2022).

Roy, A. FAIR Principles for data and AI models in high energy physics research and education. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.15021 (2022).

Torre, D. et al. Datasets2Tools, repository and search engine for bioinformatics datasets, tools and canned analyses. Scientific Data 5, 180023, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.23 (2018).

Raffaghelli, J. E. & Manca, S. Is There a Social Life in Open Data? The Case of Open Data Practices in Educational Technology Research. Publications 7 (2019).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (2023).

SNOMED International, https://www.snomed.org/ (2023).

Minimum Information About Biobank data Sharing (MIABIS), https://github.com/BBMRI-ERIC/miabis (2022).

Unified Medical Language System (UMLS), https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/index.html (2021).

Bergeron, J., Doiron, D., Marcon, Y., Ferretti, V. & Fortier, I. Fostering population-based cohort data discovery: The Maelstrom Research cataloguing toolkit. PLOS ONE 13, e0200926, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200926 (2018).

Sansone, S.-A. et al. Toward interoperable bioscience data. Nature Genetics 44, 121–126, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.1054 (2012).

German Research Foundation (DFG). National Research Data Infrastructure, https://www.dfg.de/en/research_funding/programmes/nfdi/index.html (2023).

Fluck, J. National Research Data Infrastructure for Personal Health Data (NFDI4Health) Proposal. https://doi.org/10.4126/FRL01-006421856 (2019).

McMahon, C. The evaluation and harmonisation of disparate information metamodels in support of epidemiological and public health research, Doctoral thesis (Ph.D), UCL (University College London), (2017).

Greiser, K. H. et al. Cardiovascular disease, risk factors and heart rate variability in the elderly general population: Design and objectives of the CARdiovascular disease, Living and Ageing in Halle (CARLA) Study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 5, 33, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-5-33 (2005).

Lacruz, M. E. et al. Prevalence and Incidence of Hypertension in the General Adult Population: Results of the CARLA-Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e952–e952, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000952 (2015).

Tausch, A. Inzidenz der Herzinsuffizienz in einer älteren Allgemeinbevölkerung in Halle (Saale): die CARLA-Studie (2002-2010) [Heart failure incidence in an older population in Halle (Saale): the CARLA-Study (2002-2010)]. Doctoral dissertation, Universität Halle. (2020).

Hassan, L. et al. The association between change of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor R1 (sTNF-R1) measurements and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality—Results from the population-based (Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle) CARLA study 2002–2016. PLOS ONE 15, e0241213, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241213 (2020).

Herrmann, W. J. et al. Erfassung inzidenter kardiovaskulärer und metabolischer Erkrankungen in epidemiologischen Kohortenstudien in Deutschland [Recording of incident cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in epidemiological cohort studies in Germany]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 61, 420–431, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-018-2712-4 (2018).

Hassan, L. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors, living and ageing in Halle: the CARLA study. European Journal of Epidemiology 37, 103–116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00824-7 (2022).

Univeristy Hospital Halle (Saale) & University Medicine Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. Welcome to the CARLA-Study: “Healthy living with heart” in Halle, Germany, https://webszh.uk-halle.de/carla-studie/.

Medical Data Models: MDM Portal, https://medical-data-models.org/ (2023).

Univeristy Hospital Halle (Saale) & University Medicine Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. Data Dictionaries [CARLA], https://webszh.uk-halle.de/carla-studie/index.php/variablenverzeichnisse/.

Robert Koch Institute. DEGS1: Basispublikation mit Ergebnissen [DEGS1: base publication with results], https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/degs_w1/Basispublikation/basispublikation_node.html.

Scheidt-Nave, C. et al. German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS) - design, objectives and implementation of the first data collection wave. BMC Public Health 12, 730, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-730 (2012).

Robert Koch Institute. DEGS: Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland [DEGS: German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults], https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/degs_node.html.

Robert Koch Institute. Datenangebot des Forschungsdatenzentrums [Data offer of the Research Data Center], https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Forsch/FDZ/Datenangebot/Datenangebot_node.html;jsessionid=8534447A31D0DAFAFCD994CA8EBE4D3E.internet112.

Buyken, A. E., Alexy, U., Kersting, M. & Remer, T. Die DONALD Kohorte [The DONALD cohort]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 55, 875–884, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1503-6 (2012).

Della Corte, K. A. et al. The Prospective Association of Dietary Sugar Intake in Adolescence With Risk Markers of Type 2 Diabetes in Young Adulthood. Frontiers in Nutrition 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.615684 (2021).

Goletzke, J. et al. Habitually Higher Dietary Glycemic Index During Puberty Is Prospectively Related to Increased Risk Markers of Type 2 Diabetes in Younger Adulthood. Diabetes Care 36, 1870–1876, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2063 (2013).

Krupp, D., Shi, L. & Remer, T. Longitudinal relationships between diet-dependent renal acid load and blood pressure development in healthy children. Kidney International 85, 204–210, https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.331 (2014).

Krupp, D., Westhoff, T. H., Esche, J. & Remer, T. Prospective relation of adolescent citrate excretion and net acid excretion capacity with blood pressure in young adulthood. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 315, F1228–F1235, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00144.2018 (2018).

Nyasordzi, J., Penczynski, K., Remer, T. & Buyken, A. E. Early life factors and their relevance to intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery in early adulthood. PLOS ONE 15, e0233227, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233227 (2020).

Oluwagbemigun, K. et al. Developmental trajectories of body mass index from childhood into late adolescence and subsequent late adolescence–young adulthood cardiometabolic risk markers. Cardiovascular Diabetology 18, 9, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0813-5 (2019).

Penczynski, K. J. et al. Flavonoid intake from fruit and vegetables during adolescence is prospectively associated with a favourable risk factor profile for type 2 diabetes in early adulthood. European Journal of Nutrition 58, 1159–1172, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1631-3 (2019).

Schnermann, M. E., Schulz, C.-A., Herder, C., Alexy, U. & Nöthlings, U. A lifestyle pattern during adolescence is associated with cardiovascular risk markers in young adults: results from the DONALD cohort study. Journal of Nutritional Science 10, e92, https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2021.84 (2021).

Shi, L., Krupp, D. & Remer, T. Salt, fruit and vegetable consumption and blood pressure development: a longitudinal investigation in healthy children. British Journal of Nutrition 111, 662–671, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513002961 (2014).

DONALD Studie: Studiendesign und Methoden [The Donald study: study design and methods], https://www.ernaehrungsepidemiologie.uni-bonn.de/forschung/donald-1/studiendesign.

DRKS - German Clinical Trials Register, https://www.drks.de/ (2023).

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal, https://trialsearch.who.int/ (2023).

Metadata portal for observational studies in Nutritional Epidemiology that participated in the INTIMIC project, https://mica.mdc-berlin.de/.

NFDI4Health. German Central Health Study Hub, https://csh.nfdi4health.de/mdr/ (2023).

Li, K., Kaaks, R., Linseisen, J. & Rohrmann, S. Associations of dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation with myocardial infarction and stroke risk and overall cardiovascular mortality in the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg). Heart 98, 920, https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301345 (2012).

Boeing, H., Wahrendorf, J. & Becker, N. EPIC-Germany – A Source for Studies into Diet and Risk of Chronic Diseases. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 43, 195–204, https://doi.org/10.1159/000012786 (1999).

Bergmann, M. M., Bussas, U. & Boeing, H. Follow-Up Procedures in EPIC-Germany – Data Quality Aspects. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 43, 225–234, https://doi.org/10.1159/000012789 (1999).

Li, K. et al. Primary preventive potential of major lifestyle risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in men: an analysis of the EPIC-Heidelberg cohort. European Journal of Epidemiology 29, 27–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9872-1 (2014).

Kühn, T. et al. Albumin, bilirubin, uric acid and cancer risk: results from a prospective population-based study. British Journal of Cancer 117, 1572–1579, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.313 (2017).

Nimptsch, K., Rohrmann, S., Kaaks, R. & Linseisen, J. Dietary vitamin K intake in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: results from the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Heidelberg). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 91, 1348–1358, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28691 (2010).

Srour, B. et al. Ageing-related markers and risks of cancer and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study in the EPIC-Heidelberg cohort. European Journal of Epidemiology 37, 49–65, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00828-3 (2022).

Kharazmi, E., Dossus, L., Rohrmann, S. & Kaaks, R. Pregnancy loss and risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective population-based cohort study (EPIC-Heidelberg). Heart 97, 49, https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.202226 (2011).

Li, K., Kaaks, R., Linseisen, J. & Rohrmann, S. Dietary calcium and magnesium intake in relation to cancer incidence and mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg). Cancer Causes & Control 22, 1375, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-011-9810-z (2011).

Li, K., Kaaks, R., Linseisen, J. & Rohrmann, S. Vitamin/mineral supplementation and cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German prospective cohort (EPIC-Heidelberg). European Journal of Nutrition 51, 407–413, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0224-1 (2012).

Braig, S. et al. The impact of social status inconsistency on cardiovascular risk factors, myocardial infarction and stroke in the EPIC-Heidelberg cohort. BMC Public Health 11, 104, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-104 (2011).

Lu, D.-L. et al. Circulating 27-Hydroxycholesterol and Breast Cancer Risk: Results From the EPIC-Heidelberg Cohort. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 111, 365–371, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy115 (2019).

Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft [German Cancer Research Center in the Helmholtz Association]. EPIC-Heidelberg Study, https://www.dkfz.de/de/epidemiologie-krebserkrankungen/arbeitsgr/ernaerepi/EPIC_p03_EPIC_Heidelberg.html#section2.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), https://epic.iarc.fr/access/submit_appl_access.php.

EPIC Study. Access: How to submit an application for gaining access to EPIC data and/or biospecimens?, https://epic.iarc.fr/access/submit_appl_access.php.

von Ruesten, A., Weikert, C., Fietze, I. & Boeing, H. Association of Sleep Duration with Chronic Diseases in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. PLOS ONE 7, e30972, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030972 (2012).

Drogan, D., Klipstein-Grobusch, K., Dierkes, J., Weikert, C. & Boeing, H. Dietary intake of folate equivalents and risk of myocardial infarction in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)–Potsdam study. Public Health Nutrition 9, 465–471, https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2005863 (2006).

Weikert, C. et al. Joint effects of risk factors for stroke and transient ischemic attack in a German population. Journal of Neurology 254, 315–321, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-006-0358-x (2007).

Cabral, M. et al. Trace element profile and incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: results from the EPIC-Potsdam cohort study. European Journal of Nutrition 60, 3267–3278, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02494-3 (2021).

Schulze, M. B., Hoffmann, K., Kroke, A. & Boeing, H. Risk of Hypertension among Women in the EPIC-Potsdam Study: Comparison of Relative Risk Estimates for Exploratory and Hypothesis-oriented Dietary Patterns. American Journal of Epidemiology 158, 365–373, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg156 (2003).

Spranger, J. et al. Inflammatory Cytokines and the Risk to Develop Type 2 Diabetes: Results of the Prospective Population-Based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes 52, 812–817, https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812 (2003).

Kroke, A. et al. Blood pressure measurement in epidemiological studies: a comparative analysis of two methods. Data from the EPIC-Potsdam Study. Journal of Hypertension 16 (1998).

Heidemann, C. et al. Association of a diabetes risk score with risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, specific types of cancer, and mortality: a prospective study in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam cohort. European Journal of Epidemiology 24, 281–288, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-009-9338-7 (2009).

Galbete, C. et al. Nordic diet, Mediterranean diet, and the risk of chronic diseases: the EPIC-Potsdam study. BMC Medicine 16, 99, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1082-y (2018).

German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke (DIfE). EPIC-Potsdam Study, https://www.dife.de/en/research/cooperations/epic-study/.

Gesundheitliche Lage der Bevölkerung in Deutschland [Health situation of the population in Germany]. Journal of Health Monitoring 1/2017

Lange, C. et al. Data Resource Profile: German Health Update (GEDA)—the health interview survey for adults in Germany. International Journal of Epidemiology 44, 442–450, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv067 (2015).

Fuchs, J., Busch, M., Lange, C. & Scheidt-Nave, C. Prevalence and patterns of morbidity among adults in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 55, 576–586, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1464-9 (2012).

Allen, J. et al. Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell (GEDA 2019/2020-EHIS)-Hintergrund und Methodik. (2021).

GEDA: Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell [GEDA: German Health Update], https://www.geda-studie.de/de/deutsch/ergebnisse/geda-20142015-ehis.html.

Robert Koch Institute. GEDA: Gesundheit Deutschland aktuell [GEDA: German Health Update], https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Geda/Geda_node.html;jsessionid=2BBA9A847CFD1BBA1700B1850FC469D5.internet101.

Schnabel, R. B., Johannsen, S. S., Wild, P. S. & Blankenberg, S. Prävalenz und Risikofaktoren von Vorhofflimmern in Deutschland [Prevalence and risk factors of atrial fibrillation in Germany]. Herz 40, 8–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-014-4199-6 (2015).

Raum, P. et al. Prevalence and Cardiovascular Associations of Diabetic Retinopathy and Maculopathy: Results from the Gutenberg Health Study. PLOS ONE 10, e0127188, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127188 (2015).

Wild, P. S. et al. Die Gutenberg Gesundheitsstudie [The Gutenberg Health Study]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 55, 824–830, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1502-7 (2012).

Hegewald, J. et al. Work-life conflict and cardiovascular health: 5-year follow-up of the Gutenberg Health Study. PLOS ONE 16, e0251260, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251260 (2021).

Rossnagel, K. et al. Long working hours and risk of cardiovascular outcomes and diabetes type II: five-year follow-up of the Gutenberg Health Study (GHS). International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 95, 303–312, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01786-9 (2022).

Schnabel, R. B. et al. Non-invasive peripheral vascular function, incident cardiovascular disease, and mortality in the general population. Cardiovascular Research 118, 904–912, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvab087 (2022).

Panova-Noeva, M. et al. Coagulation and inflammation in long-term cancer survivors: results from the adult population. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 16, 699–708, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13975 (2018).

Reiner, I. C. et al. The association of chronic anxiousness with cardiovascular disease and mortality in the community: results from the Gutenberg Health Study. Scientific Reports 10, 12436, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69427-8 (2020).

Wild, P. S. et al. Distribution and Categorization of Left Ventricular Measurements in the General Population. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 3, 604–613, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.911933 (2010).

Grossmann, V. et al. Profile of the Immune and Inflammatory Response in Individuals With Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 38, 1356–1364, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-3008 (2015).

Prochaska, J. H. et al. Chronic venous insufficiency, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a population study. European Heart Journal 42, 4157–4165, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab495 (2021).

Schnabel, R. B. et al. Multiple Biomarkers and Atrial Fibrillation in the General Population. PLOS ONE 9, e112486, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112486 (2014).

Münzel, T. et al. Heart rate, mortality, and the relation with clinical and subclinical cardiovascular diseases: results from the Gutenberg Health Study. Clinical Research in Cardiology 108, 1313–1323, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-019-01466-2 (2019).

Schmitt, V. H. et al. Cardiovascular profiling in the diabetic continuum: results from the population-based Gutenberg Health Study. Clinical Research in Cardiology 111, 272–283, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01879-y (2022).

Baum, C. et al. Subclinical impairment of lung function is related to mild cardiac dysfunction and manifest heart failure in the general population. International Journal of Cardiology 218, 298–304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.034 (2016).

Börschel, C. S. et al. Noninvasive peripheral vascular function and atrial fibrillation in the general population. Journal of Hypertension 37 https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002000 (2019).

Universitätsmedizin Mainz. Gutenberg Health Study, http://www.gutenberghealthstudy.org/ghs/overview.html?L=1.

Das Gesundheitswesen. Sonderheft 2 (Schwerpunktheft zum Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey 1998) [Healthcare. Special issue 2 (special issue for the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey 1998)] Volume 61, December 1999, https://www.thieme.de/statics/dokumente/thieme/final/de/dokumente/zw_das-gesundheitswesen/gesu-suppl_klein.pdf.

Robert Koch Institute. BGS98: Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey 1998 [GNHIES98: the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey 1998], https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/bgs98/bgs98_node.html;jsessionid=2C012A0D7691B05444747F0ADD205223.internet082.

Jagodzinski, A. et al. Rationale and Design of the Hamburg City Health Study. European Journal of Epidemiology 35, 169–181, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00577-4 (2020).

Kotin, J. et al. Association between periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in the Hamburg City Health Study. Journal of Periodontology 93, 1150–1160, https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.21-0464 (2022).

Lamprecht, R. et al. Cross-sectional analysis of the association of periodontitis with carotid intima media thickness and atherosclerotic plaque in the Hamburg City health study. Journal of Periodontal Research 57, 824–834, https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.13021 (2022).

Struppek, J. et al. Periodontitis, dental plaque, and atrial fibrillation in the Hamburg City Health Study. PLOS ONE 16, e0259652, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259652 (2021).

Hamburg City Health Study, http://hchs.hamburg/.

U.S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (2023).

HCHS Project [study portal for scientists], https://project.hchs.hamburg/.

Lehmann, N. et al. Value of Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification for Risk Prediction of Coronary and Cardiovascular Events. Circulation 137, 665–679, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027034 (2018).

Icks, A. et al. Diabetes incidence does not differ between subjects with and without high depressive symptoms — 5-year follow-up results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Diabetic Medicine 30, 65–69, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03724.x (2013).

Erbel, R. et al. Die Heinz Nixdorf Recall Studie [The Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 55, 809–815, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1490-7 (2012).

Bokhof, B., Eisele, L., Erbel, R. & Moebus, S. Agreement between different survey instruments to assess incident and prevalent tumors and medical records – results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Cancer Epidemiology 38, 181–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2014.01.002 (2014).

Schmermund, A. et al. Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: Rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. American Heart Journal 144, 212–218, https://doi.org/10.1067/mhj.2002.123579 (2002).

Horacek, M. et al. Prävalenz der arteriellen Hypertonie in der westdeutschen Bevölkerung [Prevalence of arterial hypertension in the West German population]. Herz 37, 721–727, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-012-3684-z (2012).

Mahabadi, A. A. et al. Association of bilirubin with coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular events in the general population without known liver disease: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. Clinical Research in Cardiology 103, 647–653, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-014-0697-z (2014).

Hoffmann, B. et al. Air Quality, Stroke, and Coronary Events. Dtsch Arztebl International 112, 195–201, https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0195 (2015).

Kara, K. et al. NT-proBNP is superior to BNP for predicting first cardiovascular events in the general population: The Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. International Journal of Cardiology 183, 155–161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.082 (2015).

Behrens, T. et al. Shift work and the incidence of prostate cancer: a 10-year follow-up of a German population-based cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 43, 560–568, https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3516 (2017).

Icks, A. et al. High Depressive Symptoms in Previously Undetected Diabetes - 10-Year Follow-Up Results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Clin Epidemiol 13, 429–438, https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S294342 (2021).

Kröger, K. et al. Prevalence of Peripheral Arterial Disease – Results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. European Journal of Epidemiology 21, 279, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-006-0015-9 (2006).

Heinz Nixdorf Recall Studie [Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study], https://www.uni-due.de/recall-studie/die-studien/hnr/.

German Biobank Registry. TMF e.V, https://www.tmf-ev.de/BiobankenRegisterEN_Alt/Registry.aspx.

Bammann, K., Lissner, L., Pigeot, I. & Ahrens, W. Instruments for health surveys in children and adolescents. (Springer International Publishing, 2019. (See also https://www.bips-institut.de/en/pages/ifhs.html; accessed 03 Aug 2022)).

Ahrens, W. et al. Cohort Profile: The transition from childhood to adolescence in European children–how I.Family extends the IDEFICS cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology 46, 1394–1395j, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw317 (2017).

Ahrens, W. et al. The IDEFICS cohort: design, characteristics and participation in the baseline survey. International Journal of Obesity 35, S3–S15, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.30 (2011).

Ahrens, W. et al. Metabolic syndrome in young children: definitions and results of the IDEFICS study. International Journal of Obesity 38, S4–S14, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.130 (2014).

IDEFICS - Identification and prevention of Dietary - and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS, https://www.ideficsstudy.eu/index.php?id=1148&L=530%27.

I.Family. IDEFICS/I.Family follow-up study - lifestyle and health, https://www.ifamilystudy.eu/.

Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology - BIPS. I.Family, https://www.bips-institut.de/forschung/forschungsergebnisse/ifamily.html.

BMC. ISRCTN registry, https://www.isrctn.com/ (2023).

NFDI4Health Task Force COVID-19 Study Portal, https://covid19.studyhub.nfdi4health.de/.

BIPS. Instruments for health surveys in children and adolescents, https://www.bips-institut.de/en/pages/ifhs.html.

Meisinger, C., Koenig, W., Baumert, J. & Döring, A. Uric Acid Levels Are Associated With All-Cause and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Independent of Systemic Inflammation in Men From the General Population. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 28, 1186–1192, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160184 (2008).

Mühlenbruch, K. et al. Update of the German Diabetes Risk Score and external validation in the German MONICA/KORA study. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 104, 459–466, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2014.03.013 (2014).

Rathmann, W. et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in Southern Germany: Target populations for efficient screening. The KORA survey 2000. Diabetologia 46, 182–189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-002-1025-0 (2003).

Seyed Khoei, N., Anton, G., Peters, A., Freisling, H. & Wagner, K.-H. The Association between Serum Bilirubin Levels and Colorectal Cancer Risk: Results from the Prospective Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) Study in Germany. Antioxidants 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9100908 (2020).

Holle, R., Happich, M., Löwel, H. & Wichmann, H. E., for the, M. K. S. G. KORA - A Research Platform for Population Based Health Research. Gesundheitswesen 67, 19–25, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-858235 (2005).

Löwel, H., Meisinger, C., Heier, M. & Hörmann, A. The Population-Based Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) Registry of the MONICA/KORA Study Region of Augsburg. Gesundheitswesen 67, 31–37, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-858241 (2005).

Arshadipour, A. et al. Impact of prenatal and childhood adversity effects around World War II on multimorbidity: results from the KORA-Age study. BMC Geriatrics 22, 115, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02793-2 (2022).

Lorbeer, R. et al. Association of antecedent cardiovascular risk factor levels and trajectories with cardiovascular magnetic resonance-derived cardiac function and structure. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 23, 2, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00698-w (2021).

Bamberg, F. et al. Subclinical Disease Burden as Assessed by Whole-Body MRI in Subjects With Prediabetes, Subjects With Diabetes, and Normal Control Subjects From the General Population: The KORA-MRI Study. Diabetes 66, 158–169, https://doi.org/10.2337/db16-0630 (2017).

Peters, A. et al. Multimorbidität und erfolgreiches Altern [Multimorbidity and successful aging]. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie [Journal for gerontology and geriatrics] 44, 41–54, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-011-0245-7 (2011).

Helmholtz Zentrum München. KORA - Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Ausburg [KORA - The Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg], https://www.helmholtz-muenchen.de/kora/index.html.

Maelstrom Research https://www.maelstrom-research.org/ (2021).

KORA.PASST: Project Application Self-Service Tool, https://helmholtz-muenchen.managed-otrs.com/external.

Hasselhorn, H. M. et al. Cohort profile: The lidA Cohort Study—a German Cohort Study on Work, Age, Health and Work Participation. International Journal of Epidemiology 43, 1736–1749, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu021 (2014).

Bergische Universität Wuppertal. lidA - leben in der Arbeit [lidA - German Cohort Study on Work, Age, Health and Work Participation], https://arbeit.uni-wuppertal.de/de/studie/.

Forschungsdatenzentrum der Bundesagentur für Arbeit im In stitut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung [Research data center of the Federal Employment Agency in the Institute for Labor Market and Vocational Research]. lidA - Survey Data, https://fdz.iab.de/en/our-data-products/archived-data/lida/.

Loeffler, M. et al. The LIFE-Adult-Study: objectives and design of a population-based cohort study with 10,000 deeply phenotyped adults in Germany. BMC Public Health 15, 691, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1983-z (2015).

Engel, C. et al. Cohort Profile: The LIFE-Adult-Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, dyac114 https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyac114 (2022).

Buchmann, N. et al. Association between lipoprotein(a) level and type 2 diabetes: no evidence for a causal role of lipoprotein(a) and insulin. Acta Diabetologica 54, 1031–1038, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-017-1036-4 (2017).

Diseases, L. L. R. C. F. C. LIFE-Adult, https://life.uni-leipzig.de/en/adults/life_adult.html.

Leipzig Health Atlas. LIFE Adult, https://www.health-atlas.de/projects/5.

LIFE-Datenportal [LIFE data portal], https://ldp.life.uni-leipzig.de/.

Schipf, S. et al. Die Basiserhebung der NAKO Gesundheitsstudie: Teilnahme an den Untersuchungsmodulen, Qualitätssicherung und Nutzung von Sekundärdaten [The baseline data collection of the NAKO Health Study: Participation in the examination modules, quality assurance and use of secondary data]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 63, 254–266, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03093-z (2020).

German National Cohort Consortium The German National Cohort: aims, study design and organization. European Journal of Epidemiology 29, 371–382, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9890-7 (2014).

Ahrens, W., Greiser, K. H., Linseisen, J., Pischon, T. & Pigeot, I. Erforschung von Erkrankungen in der NAKO Gesundheitsstudie. Die wichtigsten gesundheitlichen Endpunkte und ihre Erfassung [Research into diseases in the NAKO health study. The most important health endpoints and their recording]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 63, 376–384, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03111-0 (2020).

Nimptsch, K. et al. Selbstberichtete Krebserkrankungen in der NAKO Gesundheitsstudie: Erfassungsmethoden und erste Ergebnisse [Self-reported cancers in the NAKO health study: collection methods and first results]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 63, 385–396, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03113-y (2020).

Jaeschke, L. et al. Erfassung selbst berichteter kardiovaskulärer und metabolischer Erkrankungen in der NAKO Gesundheitsstudie: Methoden und erste Ergebnisse [Collecting self-reported cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in the NAKO health study: methods and first results]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 63, 439–451, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03108-9 (2020).

NAKO Gesundheitsstudie [NAKO: German National Cohort], https://nako.de/.

re3data.org: Registry of Research Data Repositories, https://www.re3data.org/ (2023).

NAKO Transferhub, https://transfer.nako.de/transfer/index.

Schipf, S. et al. Low total testosterone is associated with increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in men: results from the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). The Aging Male 14, 168–175, https://doi.org/10.3109/13685538.2010.524955 (2011).

Völzke, H. Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 55, 790–794, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1483-6 (2012).

Völzke, H. et al. Cohort Profile: The Study of Health in Pomerania. International Journal of Epidemiology 40, 294–307, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp394 (2011).

Völzke, H. et al. Prevalence Trends in Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors. Dtsch Arztebl International 112, 185–192, https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0185 (2015).

Angelow, A., Reber, K. C., Schmidt, C. O., Baumeister, S. E. & Chenot, J.-F. Untersuchung der Prävalenz kardiologischer Risikofaktoren in der Allgemeinbevölkerung: Ein Vergleich ambulanter ärztlicher Abrechnungsdaten mit Daten einer populationsbasierten Studie [Investigating the prevalence of cardiological risk factors in the general population: A comparison of outpatient medical billing data with data from a population-based study]. Gesundheitswesen 81, 791–800, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0588-4736 (2019).

Friedrich, N. et al. Correlates of Adverse Outcomes in Abdominally Obese Individuals: Findings from the Five-Year Followup of the Population-Based Study of Health in Pomerania. Journal of Obesity 2013, 762012, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/762012 (2013).

Hoffmann, W. et al. Not Just the Demographic Change – The Impact of Trends in Risk Factor Prevalences on the Prediction of Future Cases of Myocardial Infarction. PLOS ONE 10, e0131256, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131256 (2015).

Ittermann, T. et al. Hyperthyroxinemia is positively associated with prevalent and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in two population-based samples from Northeast Germany and Denmark. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 28, 173–179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.016 (2018).

Markus, M. R. P. et al. Prediabetes is associated with lower brain gray matter volume in the general population. The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 27, 1114–1122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.007 (2017).

Markus, M. R. P. et al. Light to Moderate Alcohol Consumption Is Associated With Lower Risk of Aortic Valve Sclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 35, 1265–1270, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304831 (2015).

Markus, M. R. P. et al. Association between hepatic steatosis and serum liver enzyme levels with atrial fibrillation in the general population: The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Atherosclerosis 245, 123–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.12.023 (2016).

Moeller, M. et al. Mortality is associated with inflammation, anemia, specific diseases and treatments, and molecular markers. PLOS ONE 12, e0175909, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175909 (2017).

Richter, A. et al. The effects of incidental findings from whole-body MRI on the frequency of biopsies and detected malignancies or benign conditions in a general population cohort study. European Journal of Epidemiology 35, 925–935, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00679-4 (2020).

Rotheudt, L. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and vascular disease in the general population. Atherosclerosis 350, 73–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.03.020 (2022).

Schmidt, C. O. et al. Die Integration von Primär- und Sekundärdaten in der Study of Health in Pomerania und die Beschreibung von klinischen Endpunkten am Beispiel Schlaganfall [The integration of primary and secondary data in the Study of Health in Pomerania and the description of clinical endpoints using stroke as an example]. Gesundheitswesen 77, e20–e25, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1395648 (2015).

Schwedhelm, E. et al. Incidence of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Predicted by Symmetric Dimethylarginine in the Population-Based Study of Health in Pomerania. PLOS ONE 9, e96875, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096875 (2014).

Völzke, H. et al. A new, accurate predictive model for incident hypertension. Journal of Hypertension 31 https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328364a16d (2013).

Völzke, H. et al. Cohort Profile Update: The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). International Journal of Epidemiology, dyac034 https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyac034 (2022).

University of Greifswald. SHIP - Study of Health in Pomerania, https://www2.medizin.uni-greifswald.de/cm/fv/ship/.

euCanSHare: An EU-Canada joint infrastructure for next-generation multi-Study Heart research, https://eucanshare.bsc.es/platform/ (2020).

synchros.eu cohort repository, https://synchros.eu/.

The MORGAM Project. Description of MORGAM Cohorts, https://www.thl.fi/morgam/index.html.

Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald, Medizinische Fakultät. FVCM Transferstelle für Daten und Biomaterialien [Transfer unit for data and biomaterials], https://www.fvcm.med.uni-greifswald.de/.

Acknowledgements

This work was done as part of the NFDI4Health Consortium (www.nfdi4health.de; accessed on 19 September 2022). We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project number 442326535.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows – C.S., K.N. and T.P.: designed the research; C.S. conducted the research; W.A., H.M.H., K.H.J., V.K., A.K., B.L., R.M., U.N., I.P., A.P., C.O.S., B.S., M.B.S., A.S., H.Z. and T.P.: provided essential materials; C.S.: wrote the manuscript; C.S., K.N. and T.P. had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwedhelm, C., Nimptsch, K., Ahrens, W. et al. Chronic disease outcome metadata from German observational studies – public availability and FAIR principles. Sci Data 10, 868 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02726-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02726-7