Abstract

This article introduces data collected in the Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid-19 Project (CAUCP), which surveyed public opinion throughout the Covid-19 pandemic in 11 democracies between March and December 2020. In this paper, we present a unique cross-country panel survey of citizens’ attitudes and behaviors during a worldwide unprecedented health, governance, and economic crisis. This dataset investigates the behavioral and attitudinal consequences of multifaceted Covid19 crisis across time and contexts. In this paper, we describe the design of the CAUCP and the descriptive features of the dataset; we also present promising research prospects.

Measurement(s) | Public Opinoin |

Technology Type(s) | Individual-level survey |

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

This article introduces data collected in the Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid-19 Project (CAUCP), which surveyed public opinion throughout the Covid-19 pandemic from March to December 2020. In this paper, we present the dataset collected in 11 advanced democracies, which is deposited in open access on the Sciences Po Dataverse. It constitutes a unique cross-country panel survey of citizens’ attitudes and behaviors during a worldwide unprecedented health, governance, and economic crisis (N = 27,100 unique respondents over four waves).

Since the Covid-19 crisis tapped into all social dimensions, or crisis characteristics, it affected most peoples’ lives, and generated unprecedented individual and collective challenges to the public’s health, the economy, and social life1. The pandemic has potentially reshaped democratic politics in general and, in particular, has affected attitudes and behaviors on a large range of political issues. We consider that investigating citizens’ adaption and responses to this crisis, as well as their (possibly enduring) consequences is relevant for several reasons. First, according to the democratic responsiveness and accountability perspectives2, governments’ responses to the crisis are conditioned by public opinion. Specifically, in the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, citizens’ (expected) preferences and partisanship have shaped governments’ response to the virus, sometimes at the expense of scientific expertise3. Most existing studies indeed link policy responses to the level of political trust, but they generally overlook other dimensions of public opinion–mostly because of a lack of reliable and comparative data4,5. Second, citizens’ reactions to Covid-19 related policies are also conditional to political attitudes and emotional reactions to the crisis. Specifically, sociodemographic characteristics, personality traits, ideology, and emotions influence compliance with public health measures6. Third, the Covid-19 pandemic has shattered economies and produced a globalized economic crisis of a major magnitude7,8. Economic crises, their perception, and the perception of government responsibility normally have significant electoral and attitudinal consequences9,10.

The unprecedented crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic has generated an enormous amount of survey research. However, because of limitations in resources, narrow methodologies, or absence of a comparative perspective, few studies allow a comprehensive assessment of public opinion from the outbreak of the crisis in March 2020 onwards. For instance, available cross-country surveys are mostly cross-sectional. Thus, they overlook the evolution of public opinion, and the durability of the effect, throughout a (at least) two year-long eventful crisis11. Further, cross-sectional studies cannot establish causal mechanisms on the determinants of public attitude formation and change. On the other hand, existing panel studies are often limited to a single country, falling short of capturing important contextual effects on political behavior12 (e.g. in Austria13 or the Netherlands14). Some studies do combine cross-country comparisons with panel designs through opt-in questions added in already existing panel surveys–although necessarily limiting the breadth of investigation15. The CAUCP addresses these issues by providing public opinion panel data from 11 advanced democracies over the year 2020 to examine the longitudinal and cross-country dynamics of citizens’ preferences, perceptions, and behavior.

The CAUCP cross-country panel survey sets to answer four broad research questions, covering four major dimensions of the effects of the Covid19 pandemic on public opinion. First, [RQ1] Behavioral and attitudinal reaction to Covid-19 related policies sets to explain the reasons why people are more or less likely to support and comply with public Covid-19 related recommendations and under which circumstances, but also how people acquire information about the pandemic. It addresses the causal mechanisms by which people perceive the salience of the pandemic and their reaction to the discourse of public authorities, media outlets, and other public opinion leaders. Second, [RQ2] Political Behavior and Attitudes investigates how people respond to the crisis in terms of political preferences, political trust, and satisfaction, policy evaluation, blame attribution, emotions, and more general preferences around the role of the State. Third, [RQ3] Electoral Behavior examines the electoral consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic to evaluate its effects (if any) on prospective electoral behavior (turnout, vote choices and vote intentions), as well as the influence of retrospective vote choice on behaviors and attitudes linked to the Covid-19 crisis. Fourth, [RQ4] Social Consequences examines the conditions under which the COVID-19 crisis increases fragmentation within societies and affects social cohesion. The survey examines the dynamics of individual economic well-being, social isolation, occupational trajectories, and patterns of socialization.

Methods

Study design

Because of its scale (4 waves, 11 countries) and the constraints of the Covid-19 pandemic, the CAUCP surveys required a resolutely collective research endeavor. The dataset on Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid19 Project (CAUCP) was developed by Sylvain Brouard and Martial Foucault at the CEVIPOF in Sciences Po (France), in close cooperation with multiple research partners and institutional support. The data collection has been piloted by a steering committee also including Michael Becher (IAST Toulouse and IE University in Madrid) and Pavlos Vasilopoulos (University of York).

Case selection

The CAUCP study aims at combining a variety of country-level characteristics in order to offer a broad geographical, sanitary, and institutional scope. The project focuses on advanced democracies, it includes respondents of countries from Western Europe (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, United Kingdom), Eastern Europe (Poland), the Americas (USA, Brazil) and Oceania (Australia, New Zealand). These countries also vary along several factors pertaining directly to the Covid-19 pandemic: intensity of the pandemic (from hardest hit countries such as Brazil, the USA and the UK, to the countries that have been least affected in terms of health such as Australia or New Zealand), but also type of policy response (from most restrictive countries such as New Zealand; France, and Italy to the less constraining countries such as Sweden, the USA and Brazil). Finally, our case selection includes variation along several institutional dimensions: length of democratic rule, centralized vs. de-centralized/federal governance, and membership to the European Union.

Survey design

The CAUCP panel data was collected (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) in four waves, from the outset of the pandemic (Wave 1 in late March 2020) and throughout 2020 (Wave 2 in April 2020, Wave 3 in June 2020, and Wave 4 in December 2020). Therefore, the first wave of the panel covers the implementation of the first health restrictions in mid-March in Europe. The data collection covered the evolution of the pandemic over the summer 2020 (lower intensity of the pandemic and loosened restrictions in the Northern hemisphere vs. higher intensity of pandemic and more stringent policies in the Southern hemisphere), and it extended to December 2020 (as the pandemic dynamic reverses again between South and North). Figure 1a shows the temporality of the waves of the CAUCP panel together with indicators on the strength of the pandemic (number of new cases and covid-related deaths16) and on the stringency of governments’ response to the pandemic (Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker17). Figure 1b summarizes the fieldwork information (date of data collection and number of respondents for each wave). Because of technical and resource constraints, surveys in Brazil, Poland, and Sweden only started from Wave 2.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaires of CAUCP surveys was designed on the basis of existing comparative public opinion studies, covering a large array of socio-demographic, political, attitudinal and behavioral characteristics, as well as questions specifically addressing the consequences of the Covid-19 crisis in terms of attitudes, political behavior, support for Covid-19 policies, and the individual socio-economic consequences of the crisis. Questionnaires have been designed and adopted throughout the fieldwork by the CAUCP Steering Committee. The questionnaire retained most questions throughout the waves to allow the longitudinal analysis of variables, but occasionally required some modifications. For instance, questionnaires were flexible between waves and countries in order to include newly salient topics (e.g. compliance with wearing masks from Wave 2 onwards) and to adapt to the countries’ specific contexts (e.g. questions on multi-level governance, or national/local elections). See Table 2 for overview of selected questions included in the questionnaires.

Ethical validation

The CAUCP data collection has been approved by the Toulouse School of Economics – Institute for Advanced Studies in Toulouse (TSE-IAST) Review Board for ethical Standards in Research in April 2020. The collection of the CAUCP dataset complies with all ethical regulations of public opinion survey data. Participants have been informed of the purpose of the study and consented to sharing their data. Individual data has been entirely anonymized. A similar process is ongoing at Sciences Po to provide the overall ethical approval.

Respondents

CAUCP surveyed of total of 27,100 uniquely identified respondents, which constitutes 53,083 observations across the four panel waves. In order to increase the representativeness of the samples, each panel wave includes a minimum of 1,000 respondents in eight countries and about 2,000 in France, Germany, and the USA.

Data Records

The data generated by the CAUCP project is available in open access on the Sciences Po Dataverse18. We have uploaded sub-datasets for each wave in each country of the study in TAB format. The country*wave sub-datasets have been cleaned to standardized variable names across country and wave sub-datasets datasets. We have also included detailed codebooks for each for each sub-dataset which describes all the variables included in each sub-dataset (variables labels, answer categories, answer labels, country specific variables) in XLSX format. All this material is available at the following link: https://data.sciencespo.fr/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.21410%2F7E4%2FEATFBW.

In addition to the individual country*wave files and documentations uploaded on the institutional repository of Sciences Po, we have uploaded a merged dataset on figshare repository19. This merged dataset includes the observations for the eleven countries and the 4 waves, as well as an extended codebook in XLSX format, detailing variable types, names, labels, values, value labels, and inclusion or not in each panel wave (this codebook includes generic question wordings, as well as separate tabs for each country which details country-specific questions and answer categories).

Technical Validation

The CAUCP included a total of 27,100 individual panelists residing in the country where they are surveyed. Online recruitment of the participants began on March 20, 2020 in Germany (Wave 1) and ended on December 11, 2020 in the USA. The CAUCP panel survey lasted for over 10 months between Wave 1 and Wave 4, and the overall full panel retention is low: 3680 respondents participated in all 4 waves (13.6% of the total sample). However, on average, respondents have participated in 1.96 waves – which ensures that almost all respondents were surveyed more than once throughout the pandemic. Table 1 details the panel structure of the CAUCP data, it presents the number of respondents in each wave; the number of respondents from Wave 1 in Waves 2, 3, and 4; and the number of respondents from each preceding wave in Waves 2, 3, and 4.

Respondents of the CAUCP panel data were selected through quota sampling, which were based on a combination of multiple socio-demographic characteristics. In the 11 countries of the panel, sampling quotas were based on gender, age, occupation, region of residence, type of environment (town size or population density). In some countries, quota samplings also include additional weighting characteristics, such as ethnicity in the USA, or education in France. The full structure of unweighted samples, weighting coefficients and targeted populations for each country and each wave is presented in Appendix A. In each survey, weighting scores were obtained thanks to RIM weighting (Random Iterative Method–‘Raking’).

Identical questionnaires were administered in all countries for each wave of the CAUCP survey–albeit some questions were adapted to country-specific characteristics (notably with regards to ideology, and political and electoral behavior). On average, respondents took around 15 minutes to answer the questionnaire from Wave 1. Because of the additional questions tailored to the development of the pandemic, questionnaires of the Waves 2, 3 and 4 required more time from respondents, and lasted around 20 minutes. (See Appendix B for average response time of each panel wave in each country).

The CAUCP consists of 317 unique variables measured in all countries (some variables were introduced or drop in different waves). Table 2 presents a selection of the most relevant topics and variables covered in CAUCP data, grouped by main research themes. In addition to the variables presented in Table 2, the CAUCP survey includes extensive information on respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, religiosity, income, education, household description, employment status and trajectory). In this overview, the variables related to a series of randomized experiments carried simultaneously to the CAUCP fieldwork are excluded. Such experiments addressed RQ1 (Behavioral and attitudinal reaction to Covid-19 related policies) and focused on individual compliance to health regulations–data and results are presented separately elsewhere20.

Usage Notes

To conclude the presentation of the CAUCP dataset, we present three key dimensions covered by our survey: policy compliance, attitudinal dynamics, and democratic accountability. We describe three key variables to study the possibly large and lasting effects of the Covid-19 crisis on social and political life.

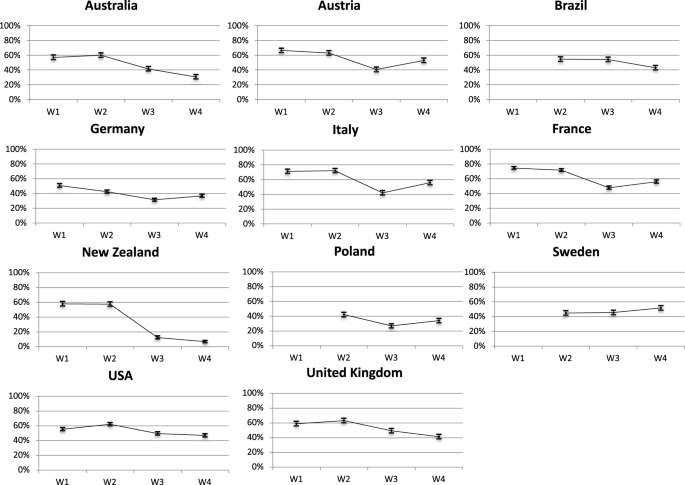

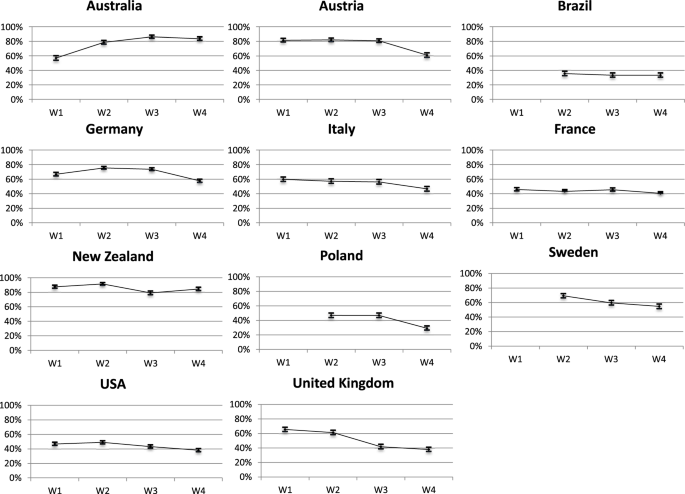

Public health policy compliance

Compliance with Covid-19 related policies is both a salient political debate and constitutes a promising research agenda. Indeed, the preventive and sometimes restrictive policies implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic have been extensively discussed in the public debate. We identify two dimensions of policy compliance: individual behavior (i.e. respecting restrictive regulations) and acceptance/evaluation of Covid-19 related measures (i.e. support for policies restricting individual and civil liberties). Despite sharp political volatility, such as decline (or variations) in trust and negative evaluations of the government, compliance levels to stringent policies remained high21,22 (Newton 2020). However, compliance is mediated by partisanship: support for the parties in government leads to greater compliance23,24. The politics of complying to stringent health policies is certainly influenced by individual and contextual factors. For instance, patterns of compliance to ‘keeping social distance’ diverge across countries, but also evolve over time (Fig. 2). Even in the case of New Zealand which has been less exposed to the coronavirus in terms of fatalities, citizens do react to the Covid-19 related policies and adapt to government recommendations. Indeed, pandemic policies are the most visible policies: virtually all citizens are aware and informed on Covid-19 restrictions. This constitutes a unique research area to evaluate both individual and contextual determinants of policy acceptance.

Compliance: Keeping distance with people outside home. Question wording: “Due to the coronavirus epidemic, in your daily life, would you say that you keep a distance of three feet (1 meter) between yourself and other people outside your home? 0 means “not at all” and 10 means “yes completely”. shows the proportion of respondents who score 10. We consider that the latter respondents are those expressing full compliance to restrictive measures.

Attitudinal dynamics

The Covid-19 pandemic had broad consequences for public attitudes. Many pundits and commentators speculate that the Covid-19 may deeply modify political cleavages. The pandemic may also polarize or de-polarize democratic societies. Alternatively, the political impact of the pandemic may be sectoral only, that is, limited to the specific dimensions linked to the crisis. Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic might not be an influential crisis, as long as citizens’ attitudes are concerned, compared to previous major crises, such as geopolitical shocks or economic crises. Still, findings suggest that the pandemic has triggered important attitudinal changes, which however mask individual-level heterogeneity within each country of our sample (for instance Galasso et al. find sizeable gender differences in attitude during the crisis25). What are the factors driving these attitudinal changes? As new issues appeared on the public agendas, there are also opportunities to study the formation of attitudes. Furthermore, many psychological traits, such as personality characteristics, risk perception, emotions are expected to influence political attitudes. Even more, the enormous amount of (mis-) information on the Covid-19 pandemic may have also influenced political attitudes. Indeed, earlier findings have found evidence that different patterns of news consumption affected levels of trust and compliance with Covid-19 related restrictions22. Descriptive findings of the CAUCP survey tend to indicate that the pandemic has not transformed overall political preferences. Indeed, average ideological preferences (Left-Right 11-point scale) are stable over the waves of the panel, and polarization seems unchanged (roughly measured with the standard deviation of the Left-Right scale). Despite a political anchor such as ideology remaining stable throughout the crisis other attitudes tend to fluctuate across time and contexts. For instance, preferences for closing borders have changed during the crisis, although in contrasted directions (Fig. 3).

Preferences for closing the borders to foreigners. Question wording: “Here is a list of measures that have been taken in some countries against the spread of coronavirus (N-Covid19). Do you agree with them? The closing of the borders for foreigners” - 5-point Likert Scale. shows the proportion of respondents who “completely agree” or “tend to agree”.

Even further, the political consequences of the pandemic seem to be mediated by anxiety rather than a cognitive trigger of the political ‘rally’ effect26. The CAUCP offers a promising agenda for research in political psychology with a large battery of questions on emotions and social interactions.

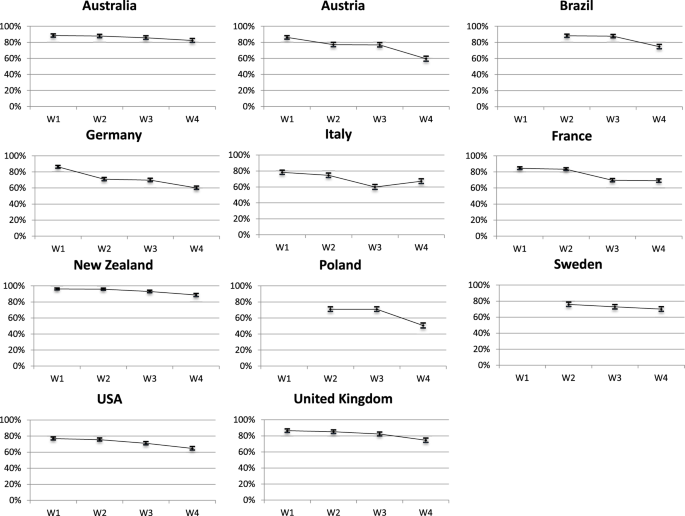

Democratic accountability

Studying the consequences of the Covid19 pandemic in terms of democratic accountability represents a rich research agenda. Citizens’ responses to the unprecedented pandemic policies, and to the subsequent expected economic crisis, is crucial to understand the functioning of democracies and will most likely be multifaceted (electoral behavior, trust and evaluation of institutions and policies, blame attribution). For instance, initial findings on citizens’ response to the Covid-19 pandemic show a ‘rally around the flag effect’27,28. However, this effect should be qualified since it is neither universal29 nor similarly lasting as the crisis endures30, or rather producing a ‘crisis signal effect that benefits incumbents’31. Research suggests that the pandemic has triggered stronger support or satisfaction with the governments and their policy – largely mediated by levels of trust and partisanship32. The CAUCP data confirms that citizens’ policy response is complex and context dependent. Looking at the satisfaction with the government’s handling of the Covid19 crisis, we observe important time and country variation (Fig. 4). Indeed, in the different countries, the level of satisfaction is extremely high (Australia, New Zealand, Austria), average (France, Italy, USA), or generally low (Brazil, Poland). Additionally, trends of satisfaction are either increasing (Australia), stable (France, New Zealand), or declining (Sweden, United Kingdom). In addition to attitudes toward the government, social science research should further investigate the electoral consequences of the crisis. Indeed, local sanitary contexts and corresponding health policies have affected turnout rates in several European local elections, increasing turnout in some cases33 or depressing it in others34,35. Further, the Covid19 pandemic has influenced voting behavior, generally to the benefit of incumbents and Green parties in local elections36. How consistent are these patterns? Are they dependent on the context of the pandemic and the policy response? Do they hold for national and local elections? Such questions enable to investigate promising research venues on the effects of retrospective vote choice on attitudes, as well as on the consequences of the crisis on prospective vote choice, and actual electoral behavior as three countries held national elections in 2020 (USA, New Zealand, and Poland). Evaluating the significance of individual-level health and economic situations on political behavior and attitudes constitute a promising research lead, as most studies examined these questions at the aggregate level thus far.

Code availability

The country*waves files of the CAUCP dataset have been merged using STATA16. The Code is available on the figshare repository.

References

van der Ven, H. & Sun, Y. Varieties of Crises: Comparing the Politics of COVID-19 and Climate Change. Glob Environ Polit 21, 13–22 (2020).

Soroka, S. N. & Wlezien, C. Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Adolph, C., Amano, K., Bang-Jensen, B., Fullman, N. & Wilkerson, J. Pandemic Politics: Timing State-Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID-19. J Health Polit Policy Law 46, 211–233 (2021).

Petridou, E. Politics and administration in times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish response to the COVID-19 crisis. Eur Policy Anal 6, 147–158 (2020).

Greer, S. L., King, E. J., Fonseca, E. M. da & Peralta-Santos, A. The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Glob Public Health 15, 1413–1416 (2020).

Brouard, S., Vasilopoulos, P. & Becher, M. Sociodemographic and Psychological Correlates of Compliance with the COVID-19 Public Health Measures in France. Can J Polit Sci 53, 253–258 (2020).

OECD. G20 GDP Growth-Third quarter of 2020, OECD. G20 GDP growth Quarterly National Accounts (2020).

Baldwin, R. & Weder di Mauro, B. Economics in the Time of COVID-19. (CEPR Press, 2020).

Lewis-Beck, M. S. & Stegmaier, M. Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes. Annu Rev Polit Sci (Palo Alto) 3, 183–219 (2000).

Hernandez, E. & Kriesi, H. The Electoral Consequences of the Financial and Economic Crisis in Europe. Eur J Polit Res 55, 203–224 (2016).

Dryhurst, S. et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res 23, 994–1006 (2020).

Devine, D., Gaskell, J., Jennings, W. & Stoker, G. Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature. Political Stud Rev 19, 274–285 (2020).

Kittel, B. et al. The Austrian Corona Panel Project: monitoring individual and societal dynamics amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Eur Polit Sci https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00294-7 (2020).

Hegewald, S. & Schraff, D. Who rallies around the flag? Evidence from panel data during the Covid-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/dwgsj (2020).

Ares, M., Bürgisser, R. & Haüsermann, S. Attitudinal Polarization Towards the Redistributive Role of the State in the Wake of the COVID-19 Crisis. J Elect Public Opin Parties 31, 41–55 (2020).

Ritchie, H. et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) [dataset]. Published online at OurWorldInData.org.

Hale, T., Webster, S., Petherick, A., Phillips, T. & Kira, B. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Blavatnik School of Government Data use policy: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY standard. (2020).

Brouard, S., Foucault, M. & Michel, E. Citizens’ Attitudes Under COVID-19 Pandemic. Sciences Po Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.21410/7E4/EATFBW. (2021).

Foucault, M., Brouard, S. & Michel, E. Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid-19 Pandemic (CAUCP dataset) https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14743575.v6 (2021).

Daoust, J.-F. et al. A guilt-free strategy increases self-reported non-compliance with COVID-19 preventive measures: Experimental evidence from 12 countries. PLOS ONE 16, e0249914 (2021).

Bargain, O. & Aminjonov, U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J Public Econ 192, 104316 (2020).

Newton, K. Government Communications, Political Trust and Compliant Social Behaviour: The Politics of Covid-19 in Britain. Polit Q 91, 502–513 (2020).

Barrios, J. M. & Hochberg, Y. Risk Perception Through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27008 (2020).

Dyevre, A. & Yeung, T. Y.-C. Partisanship and Compliance with Government Measures: Evidence from Belgium During the Covid-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3587957 (2020).

Galasso, V. et al. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. PNAS 117, 27285–27291 (2020).

Schraff, D. Political trust during the Covid-19 pandemic: Rally around the flag or lockdown effects? Eur J Polit Res 60, 1007–1017 (2021).

Baekgaard, M., Christensen, J., Madsen, J. K. & Mikkelsen, K. S. Rallying around the flag in times of COVID-19: Societal lockdown and trust in democratic institutions. JBPA 3, 1–12 (2020).

Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A. & Loewen, P. J. The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? Eur J Polit Res 68, 497–505 (2020).

Kritzinger, S. et al. Rally ‘round the flag: the COVID-19 crisis and trust in the national government. West Eur Polit 44, 1205–1231 (2021).

Herrera, H., Ordoñez, G., Konradt, M. & Trebesch, C. Corona Politics: The Cost of Mismanaging Pandemics. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3690490 (2020).

De Vries, C. E., Bakker, B. N., Hobolt, S. & Arceneaux, K. Crisis Signaling: How Italy’s Coronavirus Lockdown Affected Incumbent Support in Other European Countries. Political Sci Res Methods 9, 451–467 (2021).

Altiparmakis, A. et al. Pandemic Politics: the determinants of policy evaluation of government responses to COVID-19. West Eur Polit 44, 1159–1179 (2021).

Frank, M., Stadelmann, D. & Torgler, B. Electoral turnout during states of emergency and effects on incumbent vote share. (2020).

Brouard, S. & McAvay, H. Participation aux élections municipales 2020 en métropole: l’effet du COVID-19. (2020).

Noury, A., François, A., Gergaud, O. & Garel, A. How does COVID-19 affect electoral participation? evidence from the French municipal elections. PLOS ONE 16, e0247026 (2021).

Giommoni, T. & Loumeau, G. Lockdown and Voting Behaviour: A Natural Experiment on Postponed Elections during the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3659856 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The local implementation of surveys in individual countries has associated scholars in all the countries of the study: Christoph Hönnige (University of Hannover); Kevin Arceneaux (Temple University); Eric Bélanger (McGill University); Jean-François Daoust (University of Edinburgh), Vincent Pons (Harvard Business School and NBER); Ruth Dassonneville, Erik Lachapelle, Richard Nadeau (University of Montreal); Vincenzo Galasso (Bocconi University); Hanspeter Kriesi (European University Institute); Grégoire Rota-Graziosi (University of Auvergne); Sandra León (University Carlos III); Dominique Reynié (Sciences Po); Daniel Stegmueller (Duke University).Throughout the data collection, the CAUCP project has received financial support from the following institutional partners: Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grant ANR-20-COVI-0079), French Agency for Development (AFD), World Bank, CEVIPOF, France Stratégie, Fondapol, IPSOS – Sopra Steria, Policy Center for the New South, Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Région Occitanie, EUI, IAST funding from ANR under the Investments for the Future (“Investissements d’Avenir”) program, Grant ANR-17-EURE-0010, Unicredit Foundation, University of Hanover, CERDI (CNRS), and IE University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. and M.F. conceived the study design and oversaw the data collection (along with M.B. and P.V.). E.M. drafted the manuscript. S.B., M.F., M.B. and P.V. assisted edited the manuscript. E.M., P.H.B. and N.S. handled the data management, cleaned, and summarized the data, including preparation for open access. S.B., M.F. and M.B. secured the funding and supervision of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brouard, S., Foucault, M., Michel, E. et al. ‘Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid19’, a cross-country panel survey of public opinion in 11 advanced democracies. Sci Data 9, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01249-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01249-x

This article is cited by

-

Familydemic Cross Country and Gender Dataset on work and family outcomes during COVID-19 pandemic

Scientific Data (2023)

-

Capturing the COVID-19 Crisis through Public Health and Social Measures Data Science

Scientific Data (2022)