Being transgender can inspire these researchers and improve their work, but sometimes their research has nothing to do with their identity.

Whether as a researcher or a healthcare worker, it is difficult to break into medicine as a transgender person. Trans identity is a double-edged sword of invisibility and hypervisibility. On the one hand, trans people are probably under-represented in the field, which can make it difficult to find role models and representation. Trans people may have to fight for trans-inclusive policies that no one has thought to instate before, such as being allowed to use a chosen name rather than a legal name in internal documents and on scientific papers. On the other hand, trans scientists often feel compelled to speak out about inclusion despite the threats of discrimination and verbal abuse.

It is impossible to tell just how under-represented trans people are in science, because they have been systematically excluded from diversity counts. Many surveys that could yield this type of information, such as the 2022 Survey of Earned Doctorates, ask about sex instead of gender and give only the options of ‘male’ and ‘female’.

Recently, some organizations have begun to include trans people in their data collection. The American Association of Medical Colleges’ Matriculating Students Questionnaire, for example, has found a slow but steady rise in trans medical students in recent years, with 0.8% of the 2020 matriculating class identifying as transgender, up from 0.6% in 2017. The 2020 class includes 22,239 students, so about 156 of these future doctors are transgender. This implies that there are a substantial number of trans people in medicine already. Exactly how many is not known.

Nature Medicine spoke to four transgender medical professionals and researchers about what inspires their research, trans inclusivity in science and medicine, and the unique challenges and successes of being trans in these fields.

Ayden Scheim is an assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University in Pennsylvania. He researches the health impacts of stigma and discrimination on marginalized populations. James Mungin is a senior PhD candidate in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Physiology at Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. Before pursuing their PhD, Mungin spent six years researching infectious diseases and drug development at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, the United States Department of Agriculture, and Tuskegee University in Alabama. Kale Edmiston is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a sensory neuroscientist and studies mood and anxiety disorders. Michelle Ross is a psychotherapist and is a co-founder and Director of Holistic Wellbeing Services at CliniQ, a holistic wellbeing and sexual-health service for transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse people, run in partnership with Kings College Hospital, London. She has more than 30 years of experience in sexual health, human immunodeficiency virus and holistic wellbeing.

Ayden Scheim: Research must involve the community

Ayden Scheim did not follow a traditional career path. The sociology major chose to pursue epidemiology only after being seated next to his future principal investigator at a wedding. Speaking with her, he realized that the field just so happened to fit his exact goals in life.

“I chose to go into epidemiology because I saw the opportunity to be involved in trans health research that was really going to be directly relevant to changing policies and changing healthcare practices,” Scheim says. “That sort of applied aspect attracted me at the time, and it’s become more attractive the longer I’m in this work.”

Although Scheim’s experience as a transgender man informs his work, he does not overly rely on it. “To be frank, as a white trans man who transitioned 18 years ago, with every year that goes by, I think that my own personal experience becomes less useful for my research,” he says. Scheim asks questions of local community members to understand their needs, whether that be how trans women of color experience discrimination or what gender-affirming care looks like today. Gender-affirming care may include medical treatments such as hormone therapy or surgery, as well as non-medical care such as speech therapy and facial hair removal.“[There are] so many questions my own personal experience does not give me any special insight on,” he says.

To be sure that Scheim’s research best supports the community, he involves trans people at every stage of his projects. For example, Scheim, who is originally from Canada, investigates the experiences of trans people there through Trans PULSE Canada, of which he is a co-principal investigator. For a recent survey, he identified subpopulations of the trans community in Canada who had not been purposefully included in past research, including sex workers, Indigenous people and disabled people. Committees of trans people with these identities were crucial to helping him develop survey questions.

For Scheim, involvement must be tangible and continuous. “It’s not just about community engagement, but it’s about the [transgender] community having control over the research process and over major decision-making,” Scheim says. Part of that means remaining flexible to meet the needs of transgender people. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Scheim’s team was deep in analysis of data they had collected in 2019. But at the behest of the trans community, they put this research on hold to survey trans people about how COVID-19 impacted them, such as by affecting their mental health or interrupting their access to gender-affirming hormones or surgery.

Scheim, who has a tendency to overbook himself, is also involved in a research project in India investigating the healthcare needs of transgender men and transmasculine non-binary people there. Indian trans women colleagues asked him to consult on the project, and that consultation turned first into grant-writing and then into becoming a major player. “I try not to insert myself in new contexts where I’m an outsider or a guest, but rather work where I’m invited,” he says. As with the Canadian study, Scheim and his colleagues ask Indian transmasculine people to provide input throughout the process.

Scheim has been researching trans health for 15 years. But despite the impressive number of projects he has led, he says that he is not always respected for his work. Sometimes people credit his expertise to being a trans man and not to his substantial contributions to the field. He wishes that cisgender colleagues would see him as an expert because of his academic work and not just because of his personal identity.

That being said, being trans is important to his work. “There’s an ongoing struggle to assert that trans health research be led by trans people,” he says. In the field of epidemiology, that is exactly what he is doing.

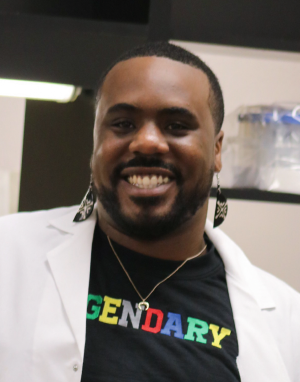

James Mungin: Educate the marginalized

James Mungin focuses on the microscopic. They are invested in the future of nanotechnology for drug delivery and are writing their thesis on the molecular mechanisms of vaginal transmission of Zika virus. But they also go big. For years, Mungin has devoted their energy to health education targeting fellow members of the queer Black community.

“I grew up in under-represented communities. I’m Black, queer, and trans non-binary,” they say. “Having that personal experience, I want to bring that to the scientific space, and also go to the community and bring my scientific expertise there.”

One way that Mungin does this is through sexual-health education. They are passionate about human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention because of the disproportionate effect this epidemic had and continues to have on queer Black and brown men. They have volunteered for several local HIV-prevention projects for people of color, including by serving on a community advisory board. “I have a commitment as far as what I can do to shift how BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] think about sexual health,” Mungin says.

Because of their history with health education, it was only natural that Mungin would turn to teaching their community about COVID-19 when the pandemic hit. “One of the things I noticed was there was a lot of misinformation and conspiracy theories. And so I just kind of wanted to, like, level that out,” they say.

One way Mungin tackles misinformation is through participating in panels and workshops. For example, they recently spoke about the vaccines against COVID-19 on a panel of medical professionals who were all people of color. Mungin has also adapted their Instagram account — @blackqueerscientist — to further their outreach. Through it, they have engaged more than 1,700 followers by providing information about COVID-19 in a way that specifically appeals to their demographic.

Their social media campaign is not huge, and it is not meant to be. It is meant to appeal to a specific population that is often ignored by science communicators. “I talk about science, but again, from more of a Black, queer, trans non-binary lens,” Mungin says. In an Instagram post, they wrote, “The level of fear and frustration my people experience is so intense that I wanted to find a solution to alleviate these pains.” Through informative graphics and videos, Mungin explains topics such as long COVID and how the virus affects pregnancy. They also express their understanding of why members of the Black community do not trust the vaccines, but Mungin makes it clear that they do and lays out why others should too.

In addition to bringing their scientific expertise to their community, Mungin also brings their personal experiences to the lab. Often this means pushing colleagues to think about inequalities in science and medicine, such as by starting conversations about whether a drug that researchers are developing will be accessible to everyone who needs it.

This year, Mungin will graduate with their PhD from Meharry Medical College. They hope to further their career as a postdoctoral researcher and study nanotechnology for targeted drug delivery to treat sexually transmitted infections. However, finding a research position is not all they have to worry about. At Meharry, people are accepting of Mungin as non-binary, but there is no guarantee that will be true wherever they end up. Mungin is not asking their peers to be perfect, but to put in the effort to be inclusive. “[My colleagues] may misgender me from time to time, but I think as long as you’re trying and giving effort, that’s something that I can rock with,” they say.

Kale Edmiston: Being trans does not define my research

Kale Edmiston is performing innovative research on how anxiety intersects with the visual system. Anxious people are more likely to interpret visual information as threatening, so he is experimenting with electrically stimulating the visual cortex to decrease activity in this region of the brain. He hopes that this stimulation could reduce symptoms of anxiety and could one day lead to a new way of treating the condition.

But when he is interviewed about his work by journalists, Edmiston finds that his research does not get the focus it deserves. He is instead asked questions that try to draw out links between his neuroscience work and his identity as a trans man. Those connections do not exist, he says. He has been asked “How does transness impact your work or inspire it?” But it does not.

This does not mean that Edmiston’s trans identity is completely separate from his work life. His secondary professional focus after mood and anxiety research is improving healthcare experiences for trans people. He has been working to improve healthcare experiences for nearly as long as he has been studying neuroscience, but these two aspects of his career remain separate.

“Trans communities everywhere are under-resourced. But in the South [of the USA], it’s just really awful,” he says. So Edmiston started going to doctor’s appointments with transgender people he did not know, such as friends of friends, and created a referral list of trans-competent providers. This work quickly became more than Edmiston could handle on his own, so he co-founded the Trans Buddy Program to get others involved. When Edmiston moved to the University of Pittsburgh, where he is now a professor, he started a local branch of the Trans Buddy Program.

“There’s a general culture of trans people not trusting the healthcare system, and there’s lots of really good reasons for that. But because of that, trans people frequently delay care and may not feel comfortable making appointments in the first place. When they do, they may not feel comfortable being forthright with a provider,” Edmiston says. “Having another person in the room, and having a list of providers that have been vetted by the community, those things can help to facilitate communication and build trust.”

Edmiston is also working on a project to write health-promotion materials for trans people. When most trans people come out, they do not know how to access transition-related services. “There’s a really long tradition of trans people sharing that knowledge amongst each other and helping guide people through that. But because all of that knowledge is shared via word of mouth, it may not necessarily be shared [widely],” he says. The Trans Buddy Program was started to make this information more accessible.

As a neuroscientist, Edmiston does not study trans people’s brains, but he does have thoughts on those who do. “I really wish that people would stop trying to focus on the neural correlates of transness. I think it’s really wrongheaded,” he says. “In the 90s, there was all this research of like, ‘Why are people gay? Let’s try and figure out the biological cause of being gay. Once we figure that out, then people won’t be homophobic anymore,’” he says. “The obvious response to that is you should just be accepting of people, no matter what.”

Instead, Edmiston would like to see more research on interventions that could improve trans lives. “There’s so much mental health disparity in the trans population. And there’s been a lot of work describing that problem for many years now,” he says. “I would love to see a shift towards mental health interventions that are designed with the trans community in mind.”

Michelle Ross: Trust takes time and effort

As a trans woman and a psychotherapist, Michelle Ross began their career by helping gay and bisexual men cope with the HIV epidemic through psychotherapy. As she continued in this field, Ross (who uses ‘she’ and ‘they’ pronouns interchangeably) learned that trans women like herself face a disproportionate HIV burden. They also have unique concerns, such as how feminizing hormones interact with HIV medications. To support these concerns, Ross began dedicating mental-health and sexual-health services to trans people in 2007. Recognizing the importance of this work, Ross surveyed the local trans community in London about their needs and opened CliniQ in 2012 as a space where trans people of all ages can receive sexual-health and holistic wellbeing services.

At other clinics, trans people are often misgendered by being called their birth name rather than their correct name, and by use of the wrong pronouns. They may be asked inappropriate and unnecessary questions about their sexuality and relationships. But because CliniQ is run mostly by trans people, with all cisgender employees and volunteers given in-depth training, it provides a much safer atmosphere for trans care. “You can’t buy that trust. You have to earn it,” Ross says.

CliniQ partners with King’s College Hospital in London to offer health services such as cervical cancer screening, which can often be uncomfortable for trans people. The medical professionals work with the patients to make them feel as safe as possible, such as by allowing them to insert the speculum themselves. If this sort of exam is traumatizing, there are counselors waiting to help patients process the experience.

Sexual-health services such as Pap smears and screening for sexually transmitted infections can be intimidating, so CliniQ has turned the weekly walk-in clinics into a lively event. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, they transformed a hospital waiting area into a community space with tea, coffee, fruit and sandwiches. Friends would meet there, and it was not uncommon for someone to play a guitar or juggle. “It’s like going home,” Ross says of these sessions. Twenty to thirty patients would receive services in a three-hour window.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 has changed that. The clinic took a three-week break, and when it returned, only three people were allowed in the waiting room at a time, with masks and social distancing. Now that many patients are vaccinated, the service has expanded to 12 appointments each Tuesday, with more becoming available soon. In CliniQ itself, demand has skyrocketed during the pandemic, particularly for teletherapy.

Beyond supporting trans people through the pandemic, Ross has big goals for CliniQ. Recently, for the first time, the United Kingdom began collecting data on trans people with HIV. This data will allow researchers to quantify how many trans people are affected by HIV. Now Ross wants the country to collect information about the prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections in the trans community. These data, or lack thereof, inform everything from CliniQ’s funding to staffing to services. “Without data, you’re invisible!” she says. “If you don’t count us, we don’t count.”

Ross also plans to expand CliniQ to cities in the United Kingdom outside of London. But she hopes that one day that will not be necessary. “We don’t want to build an empire,” they say. She would rather trans people be able to go to any health provider and receive adequate and respectful care. “We want to make sure that we’re not needed,” they say. But until that time, Ross and CliniQ will be there to care for their community.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial note: These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santora, T. How four transgender researchers are improving the health of their communities. Nat Med 27, 2074–2077 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01597-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01597-y