Abstract

Waterfalls are inspiring landforms that set the pace of landscape evolution as a result of bedrock incision1,2,3. They communicate changes in sea level or tectonic uplift throughout landscapes2,4 or stall river incision, disconnecting landscapes from downstream perturbations3,5. Here we use a flume experiment with constant water discharge and sediment feed to show that waterfalls can form from a planar, homogeneous bedrock bed in the absence of external perturbations. In our experiment, instabilities between flow hydraulics, sediment transport and bedrock erosion lead to undulating bedforms, which grow to become waterfalls. We propose that it is plausible that the origin of some waterfalls in natural systems can be attributed to this intrinsic formation process and we suggest that investigations to distinguish self-formed from externally forced waterfalls may help to improve the reconstruction of Earth history from landscapes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All topographic and water surface profiles are available in the Supplementary Information.

References

Weissel, J. K. & Seidl, M. A. in Rivers Over Rock: Fluvial Processes In Bedrock Channels (eds Tinkler, K. & Wohl, E.) 189–206 (Geophysical Monograph, AGU, Washington DC, 1998).

Whipple, K. X., DiBiase, R. A. & Crosby, B. T. in Treatise on Geomorphology Vol. 9 (eds Shroder, J. Jr & Wohl, E. E.) Ch. 9.28, 550–573 (Elsevier, London, 2013).

DiBiase, R. A., Whipple, K. X., Lamb, M. P. & Heimsath, A. M. The role of waterfalls and knickzones in controlling the style and pace of landscape adjustment in the western San Gabriel Mountains, California. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 127, 539–559 (2015).

Crosby, B. T. & Whipple, K. X. Knickpoint initiation and distribution within fluvial networks: 236 waterfalls in the Waipaoa River, North Island, New Zealand. Geomorphology 82, 16–38 (2006).

Howard, A. D., Dietrich, W. E. & Seidl, M. A. Modeling fluvial erosion on regional to continental scales. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 99, 13971–13986 (1994).

Yanites, B. J., Tucker, G. E., Mueller, K. J. & Chen, Y. G. How rivers react to large earthquakes: evidence from central Taiwan. Geology 38, 639–642 (2010).

Malatesta, L. C. & Lamb, M. P. Formation of waterfalls by intermittent burial of active faults. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 130, 522–536 (2018).

Lamb, M. P., Howard, A. D., Dietrich, W. E. & Perron, J. T. Formation of amphitheater-headed valleys by waterfall erosion after large-scale slumping on Hawai’i. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 119, 805–822 (2007).

Matthes, F. E. Geologic History of the Yosemite Valley (USGS Professional Paper 160, United States Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1930).

Gilbert, G. K. The history of the Niagara River, extracted from the sixth annual report to the commissioners of the state reservation at Niagara, Albany, NY. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015059496375;view=1up;seq=1 (1890).

Roberts, G. G., White, N. J. & Shaw, B. An uplift history of Crete, Greece, from inverse modeling of longitudinal river profiles. Geomorphology 198, 177–188 (2013).

Baynes, E. R. C., Lague, D. & Kermarrec, J. Supercritical river terraces generated by hydraulic and geomorphic interactions. Geology 46, 499–502 (2018).

Brooks, P. C. Experimental Study of Erosional Cyclic Steps. Masters thesis, Univ. Minnesota (2001).

Taki, K. & Parker, G. Transportational cyclic steps created by flow over an erodible bed. Part 1. Experiments. J. Hydraul. Res. 43, 488–501 (2005).

Yokokawa, M., Kotera, A. & Kyogoku, A. in Advances in River Sediment Research (eds S. Fukuoka et al.) 629–333 (CRC Press, Leiden, 2013).

Grimaud, J. L., Paola, C. & Voller, V. Experimental migration of knickpoints: influence of style of base-level fall and bed lithology. Earth Surf. Dyn. 4, 11–23 (2016).

Baynes, E. R. C. et al. River self-organisation inhibits discharge control on waterfall migration. Sci. Rep. 8, 2444 (2018).

Izumi, N., Yokokawa, M. & Parker, G. Incisional cyclic steps of permanent form in mixed bedrock-alluvial rivers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 122, 130–152 (2017).

Scheingross, J. S. & Lamb, M. P. A mechanistic model of plunge pool erosion into bedrock. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 122, 2079–2104 (2017).

Gardner, T. W. Experimental study of knickpoint and longitudinal profile evolution in cohesive, homogenous material. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 94, 664–672 (1983).

Holland, W. N. & Pickup, G. Flume study of knickpoint development in stratified sediment. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 87, 76–82 (1976).

Lamb, M. P. & Dietrich, W. E. The persistence of waterfalls in fractured rock. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 121, 1123–1134 (2009).

Lamb, M. P., Finnegan, N. J., Scheingross, J. S. & Sklar, L. S. New insights into the mechanics of fluvial bedrock erosion through flume experiments and theory. Geomorphology 244, 33–55 (2015).

Paola, C., Straub, K., Mohrig, D. & Reinhardt, L. The “unreasonable effectiveness” of stratigraphic and geomorphic experiments. Earth Sci. Rev. 97, 1–43 (2009).

Haviv, I. et al. Amplified erosion above waterfalls and oversteepened bedrock reaches. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 111, F04004 (2006).

Palucis, M. C. & Lamb, M. P. What controls channel form in steep mountain streams? Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7245–7255 (2017).

Lave, J. & Burbank, D. Denudation processes and rates in the Transverse Ranges, southern California: erosional response of a transitional landscape to external and anthropogenic forcing. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 109, F01006 (2004).

DiBiase, R. A., Whipple, K. X., Heimsath, A. M. & Ouimet, W. B. Landscape form and millennial erosion rates in the San Gabriel Mountains, CA. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 289, 134–144 (2010).

Hasbargen, L. E. & Paola, C. Landscape instability in an experimental drainage basin. Geology 28, 1067–1070 (2000).

Scheingross, J. S., Brun, F., Lo, D. Y., Omerdin, K. & Lamb, M. P. Experimental evidence for fluvial bedrock incision by suspended and bedload sediment. Geology 42, 523–526 (2014).

Lamb, M. P., Dietrich, W. E. & Sklar, L. S. A model for fluvial bedrock incision by impacting suspended and bed load sediment. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 113, F03025 (2008).

Finnegan, N. J., Roe, G., Montgomery, D. R. & Hallet, B. Controls on the channel width of rivers: implications for modeling fluvial incision of bedrock. Geology 33, 229–232 (2005).

Portenga, E. W. & Bierman, P. R. Understanding Earth’s eroding surface with 10Be. GSA Today 21, https://doi.org/10.1130/G111A.1 (2011).

Yerkes, R. F. & Campbell, R. H. Preliminary Geologic Map of the Los Angeles 30′ x 60′ Quadrangle, Southern California, Washington DC. Open-File Report 2005–1019 https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2005/1019/ (US Geological Survey, 2005).

Stock, G. Yosemite, CA: El Portal, Mariposa Grove, Yosemite Canyon & Tuolumne Meadows. https://doi.org/10.5069/G9GQ6VP3 (National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM), OpenTopography, 2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Preimesberger for assistance with preliminary experiments, R. DiBiase, W. Dietrich, N. Izumi, G. Parker, J. Prancevic, J. Turowski and M. Yokokawa for discussion, and A. Wickert for a review. We acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (grant EAR-1147381 to M.P.L. and a Graduate Research Fellowship to J.S.S.), NASA (grant 12PGG120107 to M.P.L.), and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (postdoctoral fellowship to J.S.S.). This work includes data services provided by the OpenTopography Facility with support from the National Science Foundation under NSF Award Numbers 1557484, 1557319 and 1557330, and EAR-1043051.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Andrew Wickert and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.S. and M.P.L. designed the study and wrote the manuscript with input from B.M.F. J.S.S. and B.M.F. performed the experiment with input from M.P.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental set-up.

a, Schematic of experimental set-up at t = 0 h. Precut steps visible downstream of the test section extent eroded rapidly to the fixed base level and did not influence the experiment or the development of cyclic steps (which developed throughout the test section). b, Photograph (taken by B.M.F.) of set-up after completion of the experiment.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Experiment photographs showing canyon incision.

a–e, Progressive incision and canyon formation with time. The dashed line highlights the x = 2.3 m cross-section; the arrow points downstream (a 15-cm-long pen is shown to give the scale). Photographs were taken (by authors) after removal of deposited sediment while the experiment was paused. f, Field example of a canyon with similar morphology to our experiment from Pleasant Creek, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah, USA (photo credit: Bret Edge).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Detail view of bedrock channel evolution.

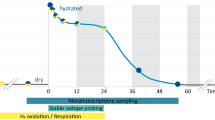

a–f, Time series of bedrock channel (black) and water surface (blue) profiles showing waterfall plunge-pool formation at x ≈ 4 m. Grey lines show previous bedrock surfaces spaced at about 0.3-h intervals and correspond to times shown in Fig. 2a; grey shading denotes areas of deposited sediment. We note that water surface profiles correspond to times about 0.1 h later than bedrock profiles and no water surface profile is available for f. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Relative vertical erosion rates at the waterfall brink and the waterfall plunge-pool floor.

a, Erosion rate versus time for the upstream waterfall centred at x = 4.3. b, Erosion rate versus time for the downstream waterfall centred at x = 6.5. During periods of waterfall formation (2.4 h < t < 3.1 h and 2.1 h < t < 2.8 h for the upstream and downstream waterfall, respectively) erosion at the pool floor (Efloor) outpaced that at the brink (Ebrink), causing an increase in waterfall height. As waterfall plunge pools deepened, their erosion rates slowed below that of the upstream brink, thereby decreasing waterfall height and destroying the original waterfall.

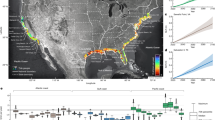

Extended Data Fig. 5 Field examples of putative autogenic waterfalls formed in concert with externally forced riverbed steepening.

a, Lidar shaded relief map of Yosemite Valley, California, USA. b, Detailed view of potentially autogenic waterfalls upstream of Bridalveil Falls (data distributed via OpenTopography35). We note that waterfalls do not align with macroscale jointing or fractures visible in the lidar. c–e, Lidar-extracted long profiles above Bridalveil (c, d) and Upper Yosemite Falls (e). Coloured dots show channel slopes above 30° calculated across a 3-pixel moving window (horizontal length scale of about 3 m). Waterfalls frequently occur at slopes less than 50°, similar to our experiment.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Field examples of putative autogenic waterfalls formed in steady-state landscapes.

a, Shaded relief map of the Central Sierra Madre Block of the San Gabriel Mountains, California, USA, showing locations of the Eaton and Rubio canyons. b, Simplified geological map of Rubio and Eaton canyons after ref. 34, mixed intrusive rocks are dominated by Cretaceous and Triassic granitoids. c, d, Detailed lidar shaded relief maps showing potentially autogenic waterfalls in the Eaton and Rubio canyons (data courtesy of the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) and available in Supplementary Data 2). e, f, Lidar-extracted long profile for Eaton and Rubio canyons with coloured dots showing channel slopes above 30° calculated across a 3-pixel moving window (horizontal length scale of about 3 m).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

Laser scans of bedrock channel profiles, sediment deposition, and water surface profiles over the course of the experiment.

Supplementary Data 2

Zipped file containing gridded, digital elevation models of bare-Earth Lidar data for Rubio Canyon and Eaton Canyon (San Gabriel Mountains). Data were collected and processed by the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) in fall 2009.

Video 1

Upstream autogenic waterfall. Video showing the presence of a waterfall with detached jet at x ~ 4 m at t ~ 3.2 hr. Video is shot primarily from an overhead perspective looking directly down at the experiment. Note that entire surface on which the flume rests (including, for example, the flume sides and the visible measuring tape) is tilted 19.5% with respect to horizontal.

Video 2

Downstream autogenic waterfall. Video showing the presence of a waterfall with detached jet at x ~ 6 m at t ~ 3.2 hr. Video is shot primarily from an overhead perspective looking directly down at the experiment. Note that entire surface on which the flume rests (including, for example, the flume sides and the visible measuring tape) is tilted 19.5% with respect to horizontal.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scheingross, J.S., Lamb, M.P. & Fuller, B.M. Self-formed bedrock waterfalls. Nature 567, 229–233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0991-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0991-z

This article is cited by

-

Identification and geomorphic characterization of fluvial knickzones in bedrock rivers from Courel Mountains Geopark

Environmental Earth Sciences (2023)

-

The bryophyte community as bioindicator of heavy metals in a waterfall outflow

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Experimental evidence that rill-bed morphology is governed by emergent nonlinear spatial dynamics

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The shaping of erosional landscapes by internal dynamics

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2020)

-

Bedrock-alluvial streams with knickpoint and plunge pool that migrate upstream with permanent form

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.