Abstract

Topological operations around exceptional points1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8—time-varying system configurations associated with non-Hermitian singularities—have been proposed as a robust approach to achieving far-reaching open-system dynamics, as demonstrated in highly dissipative microwave transmission3 and cryogenic optomechanical oscillator4 experiments. In stark contrast to conventional systems based on closed-system Hermitian dynamics, environmental interferences at exceptional points are dynamically engaged with their internal coupling properties to create rotational stimuli in fictitious-parameter domains, resulting in chiral systems that exhibit various anomalous physical phenomena9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. To achieve new wave properties and concomitant device architectures to control them, realizations of such systems in application-abundant technological areas, including communications and signal processing systems, are the next step. However, it is currently unclear whether non-Hermitian interaction schemes can be configured in robust technological platforms for further device engineering. Here we experimentally demonstrate a robust silicon photonic structure with photonic modes that transmit through time-asymmetric loops around an exceptional point in the optical domain. The proposed structure consists of two coupled silicon-channel waveguides and a slab-waveguide leakage-radiation sink that precisely control the required non-Hermitian Hamiltonian experienced by the photonic modes. The fabricated devices generate time-asymmetric light transmission over an extremely broad spectral band covering the entire optical telecommunications window (wavelengths between 1.26 and 1.675 micrometres). Thus, we take a step towards broadband on-chip optical devices based on non-Hermitian topological dynamics by using a semiconductor platform with controllable optoelectronic properties, and towards several potential practical applications, such as on-chip optical isolators and non-reciprocal mode converters. Our results further suggest the technological relevance of non-Hermitian wave dynamics in various other branches of physics, such as acoustics, condensed-matter physics and quantum mechanics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dembowski, C. et al. Experimental observation of the topological structure of exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 787–790 (2001).

Gilary, I., Mailybaev, A. A. & Moiseyev, N. Time-asymmetric quantum-state-exchange mechanism. Phys. Rev. B 88, 020102 (2013).

Doppler, J. et al. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point for asymmetric mode switching. Nature 537, 76–79 (2016).

Xu, H., Mason, D., Jiang, L. & Harris, J. G. E. Topological energy transfer in an optomechanical system with exceptional points. Nature 537, 80–83 (2016).

Choi, Y. et al. Extremely broadband, on-chip optical nonreciprocity enabled by mimicking nonlinear anti-adiabatic quantum jumps near exceptional points. Nat. Commun. 8, 14154 (2017).

Uzdin, R., Mailybaev, A. & Moiseyev, N. On the observability and asymmetry of adiabatic state flips generated by exceptional points. J. Phys. A 44, 435302 (2011).

Hassan, A. U., Zhen, B., Soljačić, M., Khajavikhan, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Dynamically encircling exceptional points: exact and polarization state conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 093002 (2017).

Milburn, T. J. et al. General description of quasiadiabatic dynamical phenomena near exceptional points. Phys. Rev. A 92, 052124 (2015).

Klaiman, S., Günther, U. & Moiseyev, N. Visualization of branch points in PT-symmetric waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 080402 (2008).

Rüter, C. E. et al. Observation of parity–time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 192–195 (2010).

Regensburger, A. et al. Parity–time synthetic photonic lattices. Nature 488, 167–171 (2012).

Chang, L. et al. Parity–time symmetry and variable optical isolation in active-passive-coupled microresonators. Nat. Photon. 8, 524–529 (2014).

Peng, B. et al. Parity–time symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat. Phys. 10, 394–398 (2014).

Feng, L., Wong, Z. J., Ma, R.-M., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. Single-mode laser by parity–time symmetry breaking. Science 346, 972–975 (2014).

Gao, T. et al. Observation of non-Hermitian degeneracies in a chaotic exciton-polariton billiard. Nature 526, 554–558 (2015).

Hahn, C. et al. Observation of exceptional points in reconfigurable non-Hermitian vector-field holographic lattices. Nat. Commun. 7, 12201 (2016).

Bender, C. M., Brody, D. C., Jones, H. F. & Meister, B. K. Faster than Hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 040403 (2007).

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 14, 11–19 (2018).

Horsley, S. A. R., Artoni, M. & La Rocca, G. C. Spatial Kramers–Kronig relations and the reflection of waves. Nat. Photon. 9, 436–439 (2015).

Chen, W., Özdemir, Ş. K., Zhao, G., Wiersig, J. & Yang, L. Exceptional points enhance sensing in an optical microcavity. Nature 548, 192–196 (2017).

Hodaei, H. et al. Enhanced sensitivity at higher-order exceptional points. Nature 548, 187–191 (2017).

Assawaworrarit, S., Yu, X. & Fan, S. Robust wireless power transfer using a nonlinear parity–time-symmetric circuit. Nature 546, 387–390 (2017).

Goldzak, T., Mailybaev, A. A. & Moiseyev, N. Light stops at exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 013901 (2018).

Bi, L. et al. On-chip optical isolation in monolithically integrated non-reciprocal optical resonators. Nat. Photon. 5, 758–762 (2011).

Fan, L. et al. An all-silicon passive optical diode. Science 335, 447–450 (2012).

Yu, Z. & Fan, S. Complete optical isolation created by indirect interband photonic transitions. Nat. Photon. 3, 91–94 (2009); corrigendum 3, 303 (2009).

Lira, H., Yu, Z., Fan, S. & Lipson, M. Electrically driven nonreciprocity induced by interband photonic transition on a silicon ship. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 033901 (2012).

Kenyon, A. J. Recent developments in rare-earth doped materials for optoelectronics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 26, 225–284 (2002).

Lin, Q., Painter, O. J. & Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear optical phenomena in silicon waveguides: modeling and applications. Opt. Express 15, 16604–16644 (2007).

Bhattacharya, P. Semiconductor Optoelectronic Devices 2nd edn (Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 1997).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Global Frontier Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, which is funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014M3A6B3063708), the Basic Science Research Program (NRF-2015R1A2A2A01007553), the Presidential Post-Doc Fellowship Program (NRF-2017R1A6A3A04011896) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant RGPIN-2016-04197). We thank J. Hong and Y. Ryu for their support in the spectroscopic phase-sensitive measurement.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Q. Gu, W. Heiss and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., J.W.Y., C.H. and S.H.S. conceived the original concept and initiated the work. J.W.Y. and Y.C. developed the theory and model. Y.C., C.H. and J.W.Y. designed the optimized device samples. K.-Y.Y. and J.Y.L. fabricated and characterized the samples with the support by Y.K., C.S.L., J.K.S. and H.-S.L. J.W.Y., G.K., C.H. and Y.C. performed the spectral measurement. J.W.Y., Y.C., G.K. and S.H.S. analysed the measurement results. All authors discussed the results. J.W.Y., Y.C., P.B. and S.H.S. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Wavelength dispersion of an EEP loop.

a, Wavelength-dependent EEP loop obtained with the proposed approach, which is based on controlling the waveguide width and photonic tunnel gap. The line colour indicates the corresponding free-space wavelength, as shown in the colour bar. EP, exceptional point. b, Wavelength-dependent EEP loop obtained with the direct index-modulation method. For a fair comparison, the Ch1 waveguide is invariant along the z axis, the direct index-modulation profile is applied only to the Ch2 waveguide, and the profile is designed such that the loop at 1.55 μm is identical to that in a at the same wavelength.

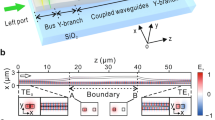

Extended Data Fig. 2 Fabrication of SiO2-encapsulated Si devices for dynamic EEP.

a, Schematic of a device array fabricated on a 10 mm × 30 mm quartz substrate. As shown in the left panel, the array consists of two control Y-branch waveguides at the top and bottom of the layout and four pairs of Si-waveguide devices in the middle (pairs 1–4, from bottom to top; see Extended Data Figs. 4–6). The control Y-branch devices have two identical straight waveguides and do not include a slab-waveguide side-patch. Each Si-waveguide device pair consists of two devices of the same length L, one on top for ACW rotation and the other at the bottom for CW rotation in the p–q plane. Each device includes an FIB-prepared input facet (in region P1; see right panel), a symmetric Y-branch (in P2), the EEP region (spanning P3–P5) and an FIB-prepared output facet (in P6). b, Optical microscope images of the characteristic device sections P1–P6 for a ACW EEP device with L = = 0.5 mm. c, d, Cross-sectional (c) and top-view (d) scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of a sacrificial device (ACW EEP with L = 0.5 mm) fabricated under the processing conditions detailed in Methods. In d, the left panel shows an image of the entire EEP device region, obtained by forming a mosaic of 79 successive SEM images, with the optimized design indicated by the red dashed curves. The right panels show close-up SEM images of P3, P4 and P5.

Extended Data Fig. 3 System used for diffraction-assisted channel interference and spectral response measurements.

Coherent infrared light from a tunable diode laser (MG9638A, Anritsu) is coupled to the device through a lensed single-mode fibre at the input facet. The actual excitation wavelength is monitored with a spectrum analyser (MS9710B, Anritsu). For precise alignment and stable input coupling, the lensed fibre is mounted on a three-axis translation-stage assembly and the sample is mounted on a six-axis translation–rotation-stage assembly. The output light is collected by a z-scanning microscope objective (numerical aperture, 0.3; working distance, 10 mm; from Nachet) imaging tube lens and an infrared camera (Model 7290A Micron Viewer, Electrophysics) to acquire z-dependent diffraction-pattern images. A broadband linear polarizer (LPNIR100-MP2, Thorlabs) is located in front of the infrared camera to filter the transverse electric component (Ex) out of the acquired image. A motorized linear stage (M-505.4PD, Physik Instrumente) with 0.25-μm unit-step resolution is used for position control of the z-scanning microscope objective. The tunable diode laser, spectrum analyser, motorized linear stage and infrared camera are connected to a desktop computer that controls them in a programed order and integrates multiple camera images for high-quality data acquisition on demand.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measured inter-channel interference patterns for device pairs 1 and 2 compared with model-fitted patterns.

a, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 1 (see Extended Data Fig. 2a). b, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 2. The device length is L = 1 mm for both device pairs 1 and 2. In the acquisition of the experimental diffraction patterns, we integrate 100 camera images to remove parasitic low-frequency electrical noise corresponding to 60-Hz harmonics. A tunable diode laser was used as the excitation source in this measurement.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Measured inter-channel interference patterns for device pairs 3 and 4 compared with model-fitted patterns.

a, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 3 (see Extended Data Fig. 2a). b, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 4. The device length is L = 0.5 mm for both device pairs 3 and 4. In the acquisition of the experimental diffraction patterns, we integrate 100 camera images to remove parasitic low-frequency electrical noise corresponding to 60-Hz harmonics. A tunable diode laser was used as the excitation source in this measurement.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Measured inter-channel interference patterns compared with the model-fitted patterns for device pairs excited by an infrared supercontinuum source.

a, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 2 (L = 1.0 mm; see Extended Data Fig. 2a). b, Patterns for ACW–CW EEP device pair 4 (L = 0.5 mm). In the acquisition of the experimental diffraction patterns, we integrate 100 camera images to remove parasitic low-frequency electrical noise corresponding to 60-Hz harmonics. In b, the experimental patterns at 1,600 nm and 1,650 nm for the ACW EEP device are missing owing to the very low signal-to-noise ratio at those conditions.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains the mathematical treatment (Supplementary Note I) for equations (1) and (2) in the main text, detailed description of the device design method (Supplementary Note II), and a detailed description of the numerical fitting procedure (Supplementary Note III) for the experimental results in Figs. 3 and 4 in the main text. This document includes Supplementary Table I, which illustrates structures and the corresponding mode-field configurations associated with the theoretical arguments in Supplementary Note I. In addition, Supplementary Figs. S1–S3 provide parametric effective-index spectra, an optimized loop, and evolution speed profiles, respectively, to support the design method described in Supplementary Note II.

Video 1

Gradual formation of the inter-channel interference patterns due to the free-space diffraction. This video shows continuous change of cross-sectional diffracted-intensity patterns of the final photonic states from the fabricated devices as the collection objective lens scans its object plane position zD from 0 to 60 μm along the optical axis. The characteristic inter-channel interference patterns are clearly identified in the diffraction patterns for zD ≥ 50 μm.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, J.W., Choi, Y., Hahn, C. et al. Time-asymmetric loop around an exceptional point over the full optical communications band. Nature 562, 86–90 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0523-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0523-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chiral transmission by an open evolution trajectory in a non-Hermitian system

Light: Science & Applications (2024)

-

Exceptional classifications of non-Hermitian systems

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Exceptional points and non-Hermitian photonics at the nanoscale

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Dynamically crossing diabolic points while encircling exceptional curves: A programmable symmetric-asymmetric multimode switch

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Non-Hermitian chiral degeneracy of gated graphene metasurfaces

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.