Abstract

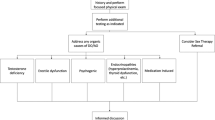

Sexual dysfunction is one of the symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) that motivates women to seek medical help. Women with POP are likely to restrict sexual activity owing to a perceived of loss of attractiveness and fear of incontinence. Conservative (pelvic floor muscles training or pessary) or surgical management (transabdominally or transvaginally) can be offered to treat POP but questions remain regarding sexual outcome. Despite the usual improvement in sexual function after surgery, a risk of de novo dyspareunia exists irrespective of the procedure used with slightly increased risk after transvaginal repair. Preoperative patient counselling, ideally with a cross-disciplinary approach is an important part of management of POP.

Key points

The effect of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) on sexual function does not correlate with its anatomical stage.

Sexual function usually improves after surgery, irrespective of the technique used; this improvement is primarily caused by improved body image in response to correction of the POP.

Sexual well-being before surgery is a major predictor of postoperative sexual well-being. Preoperative counselling is an important step before surgery.

Sacrocolpopexy remains the gold-standard treatment for POP repair, particularly in women <70 years old, with the lowest proportion of de novo dyspareunia. However, although long disparaged, vaginal surgery can be offered to sexually active patients provided the principles of good practice are followed.

The incidence of de novo dyspareunia and the global Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire score is not different between vaginal repair with or without mesh.

With the vaginal approach, occurrence of dyspareunia is much reduced with the new generation of lightweight, flexible, non-absorbable meshes but is still higher than that reported after sacrocolpopexy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fatton, B. Sexual outcome after pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Prog. Urol. 19, 1037–1059 (2009).

Nygaard, I. et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 300, 1311–1316 (2008).

Achtari, C. & Dwyer, P. L. Sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 19, 993–1008 (2005).

Verbeek, M. & Hayward, L. Pelvic floor dysfunction and its effect on quality of sexual life. Sex. Med. Rev. 7, 559–564 (2019).

Rogers, R. G. et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the pelvic organ prolapse/incontinence sexual questionnaire, IUGA-revised (PISQ-IR). Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1091–1103 (2013).

Slieker-ten Hove, M. C. et al. The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse symptoms and signs and their relation with bladder and bowel disorders in a general female population. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 20, 1037–1045 (2009).

Handa, V. L., Garrett, E., Hendrix, S., Gold, E. & Robbins, J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190, 27–32 (2004).

Nygaard, I., Bradley, C., Brandt, D. & Women’s, H. I. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet. Gynecol. 104, 489–497 (2004).

Zeleke, B. M., Bell, R. J., Billah, B. & Davis, S. R. Symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling older Australian women. Maturitas 85, 34–41 (2016).

Samuelsson, E. C., Victor, F. T., Tibblin, G. & Svärdsudd, K. F. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 180, 299–305 (1999).

Tegerstedt, G., Maehle-Schmidt, M., Nyrén, O. & Hammarström, M. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in a Swedish population. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 16, 497–503 (2005).

Vierhout, M. E., Stoutjesdijk, J. & Spruijt, J. A comparison of preoperative and intraoperative evaluation of patients undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 17, 46–49 (2006).

Dietz, H. P. Pelvic organ prolapse — a review. Aust. Fam. Physician 44, 446–452 (2015).

Machin, S. E. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Pelvic organ prolapse: review of the aetiology, presentation, diagnosis and management. Menopause Int. 17, 132–136 (2011).

Vergeldt, T. F., Weemhoff, M., IntHout, J. & Kluivers, K. B. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: a systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 26, 1559–1573 (2015).

Iglesia, C. B. & Smithling, K. R. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am. Fam. Physician 96, 179–185 (2017).

Ellerkmann, R. M. et al. Correlation of symptoms with location and severity of pelvic organ prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185, 1332–1337 (2001).

Løwenstein, E., Ottesen, B. & Gimbel, H. Incidence and lifetime risk of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Denmark from 1977 to 2009. Int. Urogynecol. J. 26, 49–55 (2015).

Smith, F. J., Holman, C. D., Moorin, R. E. & Tsokos, N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 116, 1096–1100 (2010).

Wu, J. M., Matthews, C. A., Conover, M. M., Pate, V. & Jonsson Funk, M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 123, 1201–1206 (2014).

Barber, M. D. Pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ 354, i3853 (2016).

Hagen, S. et al. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383, 796–806 (2014).

Li, C., Gong, Y. & Wang, B. The efficacy of pelvic floor muscle training for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 27, 981–992 (2016).

Panman, C. et al. Two-year effects and cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training in mild pelvic organ prolapse: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BJOG 124, 511–520 (2017).

Radnia, N. et al. Patient satisfaction and symptoms improvement in women using a vginal pessary for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. J. Med. Life 12, 271–275 (2019).

Rantell, A. Vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse and their impact on sexual function. Sex. Med. Rev. 7, 597–603 (2019).

Jonsson Funk, M. et al. Trends in use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 208, e1–e7 (2013).

Farthmann, J. et al. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 291, 573–577 (2015).

Richter, L. A. & Sokol, A. I. Pelvic organ prolapse–vaginal and laparoscopic mesh: the evidence. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 43, 83–92 (2016).

No authors listed]. Pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 23, 353–364 (2017).

Thompson, J. C. & Rogers, R. G. Surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse and its impact on sexual function. Sex. Med. Rev. 4, 213–220 (2016).

Ridgeway, B. M. Does prolapse equal hysterectomy? The role of uterine conservation in women with uterovaginal prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 213, 802–809 (2015).

Gutman, R. E. Does the uterus need to be removed to correct uterovaginal prolapse. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 28, 435–440 (2016).

Korbly, N. B. et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 209, 470.e1–6 (2013).

Frick, A. C. et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 19, 103–109 (2013).

van IJsselmuiden, M. N. et al. Dutch women’s attitudes towards hysterectomy and uterus preservation in surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 220, 79–83 (2017).

Cheon, C. & Maher, C. Economics of pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1873–1876 (2013).

Joint Writing Group of the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association. Joint position statement on the management of mesh-related complications for the FPMRS specialist. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 26, 219–232 (2020).

US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. FDA https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants (2019).

Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 2072–2078 (2008).

Myers, E. M. et al. Randomized trial of a web-based tool for prolapse: impact on patient understanding and provider counseling. Int. Urogynecol. J. 25, 1127–1132 (2014).

Anger, J. T. et al. Robotic compared with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 123, 5–12 (2014).

Kinman, C. L. et al. Use of an iPad™ application in preoperative counseling for pelvic reconstructive surgery: a randomized trial. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 1289–1295 (2017).

Kenton, K., Pham, T., Mueller, E. & Brubaker, L. Patient preparedness: an important predictor of surgical outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197, 654.e1–6 (2007).

Hallock, J. L., Rios, R. & Handa, V. L. Patient satisfaction and informed consent for surgery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 217, 181.e1–181.e7 (2017).

Anger, J. T. et al. Health literacy and disease understanding among aging women with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 18, 340–343 (2012).

Pakbaz, M., Rolfsman, E. & Löfgren, M. Are women adequately informed before gynaecological surgery. BMC Womens Health 17, 68 (2017).

Bovbjerg, V. E. et al. Patient-centered treatment goals for pelvic floor disorders: association with quality-of-life and patient satisfaction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200, 568.e1–6 (2009).

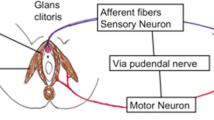

Fatton, B., de Tayrac, R. & Costa, P. Stress urinary incontinence and LUTS in women–effects on sexual function. Nat. Rev. Urol. 11, 565–578 (2014).

Kamińska, A., Futyma, K., Romanek-Piva, K., Streit-Ciećkiewicz, D. & Rechberger, T. Sexual function specific questionnaires as a useful tool in management of urogynecological patients — review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 234, 126–130 (2019).

Omotosho, T. B. & Rogers, R. G. Shortcomings/strengths of specific sexual function questionnaires currently used in urogynecology: a literature review. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 20, S51–S56 (2009).

Rogers, R. G., Coates, K. W., Kammerer-Doak, D., Khalsa, S. & Qualls, C. A short form of the pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 14, 164–168 (2003).

Rogers, R. G. et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the assessment of sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 37, 1220–1240 (2018).

Barber, M. D. et al. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 99, 281–289 (2002).

Handa, V. L., Cundiff, G., Chang, H. H. & Helzlsouer, K. J. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet. Gynecol. 111, 1045–1052 (2008).

Jha, S. & Gray, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int. Urogynecol. J. 26, 321–327 (2015).

Lowenstein, L. et al. Sexual function is related to body image perception in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J. Sex. Med. 6, 2286–2291 (2009).

Roos, A. M., Thakar, R., Sultan, A. H., Burger, C. W. & Paulus, A. T. Pelvic floor dysfunction: women’s sexual concerns unraveled. J. Sex. Med. 11, 743–752 (2014).

Culligan, P. J., Haughey, S., Lewis, C., Priestley, J. & Salamon, C. Sexual satisfaction changes reported by men after their partners’ robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexies. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 25, 365–368 (2018).

Yaakobi, T. et al. Direct and indirect effects of personality traits on psychological distress in women with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 23, 412–416 (2017).

Lowenstein, L., Pierce, K. & Pauls, R. Urogynecology and sexual function research. How are we doing? J. Sex. Med. 6, 199–204 (2009).

Barber, M. D. et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 114, 600–609 (2009).

Altman, D. et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1826–1836 (2011).

Hoda, M. R., Wagner, S., Greco, F., Heynemann, H. & Fornara, P. Prospective follow-up of female sexual function after vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using transobturator mesh implants. J. Sex. Med. 8, 914–922 (2011).

Cundiff, G. W. et al. Risk factors for mesh/suture erosion following sacral colpopexy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, 688.e1–5 (2008).

Nygaard, I. et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA 309, 2016–2024 (2013).

Vandendriessche, D. et al. Complications and reoperations after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with a mean follow-up of 4 years. Int. Urogynecol. J. 28, 231–239 (2017).

Deval, B., Rafii, A., Azria, E., Daraï, E. & Levardon, M. Vaginal mesh erosion 7 years after a sacral colpopexy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 82, 674–675 (2003).

Kemp, M. M. et al. Transrectal mesh erosion requiring bowel resection. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 24, 717–721 (2017).

Balzarro, M., Rubilotta, E., Sarti, A., Curti, P. & Artibani, W. A unique case of late complication of rectum mesh erosion after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Urol. Int. 92, 363–365 (2014).

Sarlos, D., Kots, L., Ryu, G. & Schaer, G. Long-term follow-up of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 25, 1207–1212 (2014).

Jacquetin, B. et al. Total transvaginal mesh (TVM) technique for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: a 5-year prospective follow-up study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1679–1686 (2013).

Nieminen, K. et al. Outcomes after anterior vaginal wall repair with mesh: a randomized, controlled trial with a 3 year follow-up. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 203, 235.e1–8 (2010).

Zielinski, R., Miller, J., Low, L. K., Sampselle, C. & DeLancey, J. O. The relationship between pelvic organ prolapse, genital body image, and sexual health. Neurourol. Urodyn. 31, 1145–1148 (2012).

Lukacz, E. S. et al. Quality of life and sexual function 2 years after vaginal surgery for prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 127, 1071–1079 (2016).

Huang, A. J. et al. Vaginal symptoms in postmenopausal women: self-reported severity, natural history, and risk factors. Menopause 17, 121–126 (2010).

Tyagi, V., Perera, M., Guerrero, K., Hagen, S. & Pringle, S. Prospective observational study of the impact of vaginal surgery (pelvic organ prolapse with or without urinary incontinence) on female sexual function. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 837–845 (2018).

Handa, V. L. et al. Sexual function before and after sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197, 629.e1–6 (2007).

Marschke, J., Hengst, L., Schwertner-Tiepelmann, N., Beilecke, K. & Tunn, R. Transvaginal single-incision mesh reconstruction for recurrent or advanced anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 291, 1081–1087 (2015).

Higgs, P., Goh, J., Krause, H., Sloane, K. & Carey, M. Abdominal sacral colpopexy: an independent prospective long-term follow-up study. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 45, 430–434 (2005).

Andersen, L. L. et al. Five-year follow up of a randomised controlled trial comparing subtotal with total abdominal hysterectomy. BJOG 122, 851–857 (2015).

Flory, N., Bissonnette, F., Amsel, R. T. & Binik, Y. M. The psychosocial outcomes of total and subtotal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 3, 483–491 (2006).

Thakar, R. & Sultan, A. H. Hysterectomy and pelvic organ dysfunction. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 19, 403–418 (2005).

Zucchi, A. et al. Female sexual dysfunction in urogenital prolapse surgery: colposacropexy vs. hysterocolposacropexy. J. Sex. Med. 5, 139–145 (2008).

Detollenaere, R. J. et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: multicentre randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ 351, h3717 (2015).

Zobbe, V. et al. Sexuality after total vs. subtotal hysterectomy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 83, 191–196 (2004).

Costantini, E. et al. Changes in female sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse repair: role of hysterectomy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1481–1487 (2013).

McPherson, K. et al. Psychosexual health 5 years after hysterectomy: population-based comparison with endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Health Expect. 8, 234–243 (2005).

Abramov, Y. et al. Do alterations in vaginal dimensions after reconstructive pelvic surgeries affect the risk for dyspareunia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 192, 1573–1577 (2005).

Given, F. T., Muhlendorf, I. K. & Browning, G. M. Vaginal length and sexual function after colpopexy for complete uterovaginal eversion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 169, 284–287 (1993).

Tunuguntla, H. S. & Gousse, A. E. Female sexual dysfunction following vaginal surgery: a review. J. Urol. 175, 439–446 (2006).

Weber, A. M., Walters, M. D., Piedmonte, M. R. & Ballard, L. A. Anterior colporrhaphy: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185, 1299–1304 (2001).

Colombo, M., Vitobello, D., Proietti, F. & Milani, R. Randomised comparison of Burch colposuspension versus anterior colporrhaphy in women with stress urinary incontinence and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. BJOG 107, 544–551 (2000).

Dua, A., Jha, S., Farkas, A. & Radley, S. The effect of prolapse repair on sexual function in women. J. Sex. Med. 9, 1459–1465 (2012).

Haase, P. & Skibsted, L. Influence of operations for stress incontinence and/or genital descensus on sexual life. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 67, 659–661 (1988).

Nieminen, K., Hiltunen, K. M., Laitinen, J., Oksala, J. & Heinonen, P. K. Transanal or vaginal approach to rectocele repair: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Dis. Colon. Rectum 47, 1636–1642 (2004).

Novi, J. M., Bradley, C. S., Mahmoud, N. N., Morgan, M. A. & Arya, L. A. Sexual function in women after rectocele repair with acellular porcine dermis graft vs site-specific rectovaginal fascia repair. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 18, 1163–1169 (2007).

Paraiso, M. F., Barber, M. D., Muir, T. W. & Walters, M. D. Rectocele repair: a randomized trial of three surgical techniques including graft augmentation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 195, 1762–1771 (2006).

Vollebregt, A., Fischer, K., Gietelink, D. & van der Vaart, C. H. Primary surgical repair of anterior vaginal prolapse: a randomised trial comparing anatomical and functional outcome between anterior colporrhaphy and trocar-guided transobturator anterior mesh. BJOG 118, 1518–1527 (2011).

Shatkin-Margolis, A. & Pauls, R. N. Sexual function after prolapse repair. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 29, 343–348 (2017).

Kahn, M. A. & Stanton, S. L. Posterior colporrhaphy: its effects on bowel and sexual function. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 104, 82–86 (1997).

Weber, A. M., Walters, M. D. & Piedmonte, M. R. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 182, 1610–1615 (2000).

Ulrich, D., Dwyer, P., Rosamilia, A., Lim, Y. & Lee, J. The effect of vaginal pelvic organ prolapse surgery on sexual function. Neurourol. Urodyn. 34, 316–321 (2015).

Kenton, K., Shott, S. & Brubaker, L. Outcome after rectovaginal fascia reattachment for rectocele repair. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 181, 1360–1363 (1999).

Porter, W. E., Steele, A., Walsh, P., Kohli, N. & Karram, M. M. The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 181, 1353–1358 (1999).

Sardeli, C., Axelsen, S. M., Kjaer, D. & Bek, K. M. Outcome of site-specific fascia repair for rectocele. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 86, 973–977 (2007).

Schiavi, M. C. et al. Vaginal native tissue repair for posterior compartment prolapse: long-term analysis of sexual function and quality of life in 151 patients. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 24, 419–423 (2017).

Maher, C. et al. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD012079 (2016).

Doumerc, N. et al. [Efficacy and safety of Pelvicol in the vaginal treatment of prolapse]. Prog. Urol. 16, 58–61 (2006).

Lim, Y. N. et al. A long-term review of posterior colporrhaphy with Vypro 2 mesh. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 18, 1053–1057 (2007).

Lopes, E. D. et al. Transvaginal polypropylene mesh versus sacrospinous ligament fixation for the treatment of uterine prolapse: 1-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 389–394 (2010).

Milani, R. et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG 112, 107–111 (2005).

Deffieux, X. et al. Prevention of complications related to the use of prosthetic meshes in prolapse surgery: guidelines for clinical practice. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 165, 170–180 (2012).

Clemons, J. L. et al. Impact of the 2011 FDA transvaginal mesh safety update on AUGS members’ use of synthetic mesh and biologic grafts in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 19, 191–198 (2013).

Skoczylas, L. C., Turner, L. C., Wang, L., Winger, D. G. & Shepherd, J. P. Changes in prolapse surgery trends relative to FDA notifications regarding vaginal mesh. Int. Urogynecol. J. 25, 471–477 (2014).

Chapple, C. R. et al. Consensus statement of the European Urology Association and the European Urogynaecological Association on the use of implanted materials for treating pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Eur. Urol. 72, 424–431 (2017).

Altman, D. et al. Pelvic organ prolapse repair using the uphold™ vaginal support system: a 1-year multicenter study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 27, 1337–1345 (2016).

Long, C. Y. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes using “elevate anterior” versus “Perigee” system devices for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 479610 (2015).

Rogowski, A. et al. Retrospective comparison between the Prolift and Elevate anterior vaginal mesh procedures: 18-month clinical outcome. Int. Urogynecol. J. 26, 1815–1820 (2015).

Schimpf, M. O. et al. Graft and mesh use in transvaginal prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 128, 81–91 (2016).

Glazener, C. M. et al. Mesh, graft, or standard repair for women having primary transvaginal anterior or posterior compartment prolapse surgery: two parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled trials (PROSPECT). Lancet 389, 381–392 (2017).

Nieminen, K. et al. Symptom resolution and sexual function after anterior vaginal wall repair with or without polypropylene mesh. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 19, 1611–1616 (2008).

Carey, M. et al. Vaginal repair with mesh versus colporrhaphy for prolapse: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 116, 1380–1386 (2009).

Withagen, M. I., Milani, A. L., den Boon, J., Vervest, H. A. & Vierhout, M. E. Trocar-guided mesh compared with conventional vaginal repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 117, 242–250 (2011).

de Tayrac, R. et al. Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 18, 251–256 (2007).

Lowman, J. K., Jones, L. A., Woodman, P. J. & Hale, D. S. Does the Prolift system cause dyspareunia? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, 707.e1–6 (2008).

Milani, A. L., Withagen, M. I., The, H. S., Nedelcu-van der Wijk, I. & Vierhout, M. E. Sexual function following trocar-guided mesh or vaginal native tissue repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 8, 2944–2953 (2011).

Letouzey, V. et al. Utero-vaginal suspension using bilateral vaginal anterior sacrospinous fixation with mesh: intermediate results of a cohort study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 26, 1803–1807 (2015).

Campbell, P., Cloney, L. & Jha, S. Abdominal versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 71, 435–442 (2016).

Ganatra, A. M. et al. The current status of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a review. Eur. Urol. 55, 1089–1103 (2009).

Deffieux, X. et al. Prevention of the complications related to the use of prosthetic meshes in prolapse surgery: guidelines for clinical practice — literature review [French]. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 40, 827–850 (2011).

De Gouveia De Sa, M., Claydon, L. S., Whitlow, B. & Dolcet Artahona, M. A. Robotic versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for treatment of prolapse of the apical segment of the vagina: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 27, 355–366 (2016).

Pan, K., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Y. & Xu, H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of conventional laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 132, 284–291 (2016).

Paraiso, M. F., Jelovsek, J. E., Frick, A., Chen, C. C. & Barber, M. D. Laparoscopic compared with robotic sacrocolpopexy for vaginal prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 118, 1005–1013 (2011).

van Zanten, F., Brem, C., Lenters, E., Broeders, I. A. M. J. & Schraffordt Koops, S. E. Sexual function after robot-assisted prolapse surgery: a prospective study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 905–912 (2018).

Salamon, C. G., Lewis, C. M., Priestley, J. & Culligan, P. J. Sexual function before and 1 year after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 20, 44–47 (2014).

Benson, J. T., Lucente, V. & McClellan, E. Vaginal versus abdominal reconstructive surgery for the treatment of pelvic support defects: a prospective randomized study with long-term outcome evaluation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 175, 1418–1421 (1996).

Lo, T. & Wang, A. Abdominal colposacropexy and sacrospinous ligament suspension for severe uterovaginal prolpase. J. Gynecol. Surg. 14, 59–64 (1998).

Maher, C. F. et al. Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190, 20–26 (2004).

Maher, C. et al. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD012376 (2016).

Atkins, D. et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 328, 1490 (2004).

Siddiqui, N. Y. et al. Mesh sacrocolpopexy compared with native tissue vaginal repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 125, 44–55 (2015).

Gupta, P. et al. Analysis of changes in sexual function in women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse repair with abdominal or vaginal approaches. Int. Urogynecol. J. 27, 1919–1924 (2016).

Descargues, G., Collard, P. & Grise, P. [Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: laparoscopic or vaginal sacrocolpopexy?]. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. 36, 978–983 (2008).

Maher, C. F. et al. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vaginal vault prolapse: a randomized trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204, 360.e1–7 (2011).

Lucot, J. P. et al. [PROSPERE randomized controlled trial: laparoscopic sacropexy versus vaginal mesh for cystocele POP repair]. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 42, 334–341 (2013).

Lucot, J. P. et al. Safety of vaginal mesh surgery versus laparoscopic mesh sacropexy for cystocele repair: results of the prosthetic pelvic floor repair randomized controlled trial. Eur. Urol. 74, 167–176 (2018).

Gauruder-Burmester, A., Koutouzidou, P. & Tunn, R. Effect of vaginal polypropylene mesh implants on sexual function. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 142, 76–80 (2009).

Shveiky, D., Sokol, A. I., Gutman, R. E., Kudish, B. I. & Iglesia, C. B. Patient goal attainment in vaginal prolapse repair with and without mesh. Int. Urogynecol. J. 23, 1541–1546 (2012).

Pilzek, A. L., Raker, C. A. & Sung, V. W. Are patients’ personal goals achieved after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 25, 347–350 (2014).

Lowenstein, L. et al. Changes in sexual function after treatment for prolapse are related to the improvement in body image perception. J. Sex. Med. 7, 1023–1028 (2010).

Fernando, R. J., Thakar, R., Sultan, A. H., Shah, S. M. & Jones, P. W. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 108, 93–99 (2006).

Patel, M. S., Mellen, C., O’Sullivan, D. M. & Lasala, C. A. Pessary use and impact on quality of life and body image. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 17, 298–301 (2011).

Meriwether, K. V. et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J. Sex. Med. 12, 2339–2349 (2015).

Karmakar, D. Commentary on “Sexual function after robot-assisted prolapse surgery: a prospective study”. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 921 (2018).

Weber, A. M., Walters, M. D., Schover, L. R. & Mitchinson, A. Vaginal anatomy and sexual function. Obstet. Gynecol. 86, 946–949 (1995).

Gungor, T. et al. Influence of anterior colporrhaphy with colpoperineoplasty operations for stress incontinence and/or genital descent on sexual life. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 47, 248–250 (1997).

Rogers, G. R., Villarreal, A., Kammerer-Doak, D. & Qualls, C. Sexual function in women with and without urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 12, 361–365 (2001).

Burrows, L. J., Meyn, L. A., Walters, M. D. & Weber, A. M. Pelvic symptoms in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 104, 982–988 (2004).

Ozel, B., White, T., Urwitz-Lane, R. & Minaglia, S. The impact of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function in women with urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 17, 14–17 (2006).

Novi, J. M., Jeronis, S., Morgan, M. A. & Arya, L. A. Sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse compared to women without pelvic organ prolapse. J. Urol. 173, 1669–1672 (2005).

Jelovsek, J. E. & Barber, M. D. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194, 1455–1461 (2006).

Pauls, R. N., Segal, J. L., Silva, W. A., Kleeman, S. D. & Karram, M. M. Sexual function in patients presenting to a urogynecology practice. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 17, 576–580 (2006).

Tok, E. C. et al. The effect of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function in a general cohort of women. J. Sex. Med. 7, 3957–3962 (2010).

Athanasiou, S., Grigoriadis, T., Chalabalaki, A., Protopapas, A. & Antsaklis, A. Pelvic organ prolapse contributes to sexual dysfunction: a cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 91, 704–709 (2012).

Fashokun, T. B. et al. Sexual activity and function in women with and without pelvic floor disorders. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 91–97 (2013).

Edenfield, A. L., Levin, P. J., Dieter, A. A., Amundsen, C. L. & Siddiqui, N. Y. Sexual activity and vaginal topography in women with symptomatic pelvic floor disorders. J. Sex. Med. 12, 416–423 (2015).

Cervigni, M., Natale, F., La Penna, C., Panei, M. & Mako, A. Transvaginal cystocele repair with polypropylene mesh using a tension-free technique. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 19, 489–496 (2008).

Sentilhes, L. et al. Sexual function in women before and after transvaginal mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 19, 763–772 (2008).

Jacquetin, B. et al. Total transvaginal mesh (TVM) technique for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: a 3-year prospective follow-up study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 1455–1462 (2010).

Moore, R. D. et al. Prospective multicenter trial assessing type I, polypropylene mesh placed via transobturator route for the treatment of anterior vaginal prolapse with 2-year follow-up. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 545–552 (2010).

Long, C. Y. et al. Comparison of clinical outcome and urodynamic findings using “Perigee and/or Apogee” versus “Prolift anterior and/or posterior” system devices for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 22, 233–239 (2011).

El Haddad, R. et al. Women’s quality of life and sexual function after transvaginal anterior repair with mesh insertion. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 167, 110–113 (2013).

Hugele, F. et al. Two years follow up of 270 patients treated by transvaginal mesh for anterior and/or apical prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 208, 16–22 (2017).

Laso-García, I. M. et al. Prospective long-term results, complications and risk factors in pelvic organ prolapse treatment with vaginal mesh. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 211, 62–67 (2017).

Nguyen, J. N. & Burchette, R. J. Outcome after anterior vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 111, 891–898 (2008).

de Tayrac, R. et al. Comparison between trans-obturator trans-vaginal mesh and traditional anterior colporrhaphy in the treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse: results of a French RCT. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 1651–1661 (2013).

Mangir, N., Aldemir Dikici, B., Chapple, C. R. & MacNeil, S. Landmarks in vaginal mesh development: polypropylene mesh for treatment of SUI and POP. Nat. Rev. Urol. 16, 675–689 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Review criteria

Medline and PubMed databases were searched without date or language restriction for original articles focusing on sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) using the search terms “sexual function”, “sexual outcome”, “dyspareunia”, “female sexual dysfunction”, “female sexual disorders”, “de novo dyspareunia”, “sacrocolpopexy”, “transvaginal repair”, “transvaginal mesh repair”, “mesh repair”, “native tissue repair”, “pelvic organ prolapse”, “genital prolapse”, “pelvic organ prolapse surgery”, “vaginal surgery”, “laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy” and “robotic sacrocolpopexy”. Reference lists of identified articles were also searched. Relevant data and results were then commented on and discussed and the authors have provided their interpretation of the literature. Priority was given to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), large studies using validated questionnaires and systematic reviews. Retrospective studies and/or studies with small sample sizes have also been included if they provided additional and interesting data in the field of sexual function in women with POP before or after surgery. Owing to the paucity of data on the effect of POP surgery on sexual function, several studies (including RCTs) with incomplete sexual data and some papers with small sample sizes have been included.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article, made a substantial contribution to discussion of the content, and reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission. B.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.F. is a consultant for Astellas, Allergan and Boston Scientific. R.d.T. is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Coloplast. V.L. is a consultant for Cook. S.H. declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Urology thanks L. Cardozo, X. Deffieux, C. Maher, R. Dmochowski and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fatton, B., de Tayrac, R., Letouzey, V. et al. Pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Nat Rev Urol 17, 373–390 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-020-0334-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-020-0334-8

This article is cited by

-

A Comprehensive Evaluation of Sexual Life in Women After Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy using PISQ-IR

International Urogynecology Journal (2024)

-

Evaluation for causal effects of socioeconomic traits on risk of female genital prolapse (FGP): a multivariable Mendelian randomization analysis

BMC Medical Genomics (2023)

-

Shared decision-making in urology and female pelvic floor medicine and reconstructive surgery

Nature Reviews Urology (2022)

-

Urinary and sexual impact of pelvic reconstructive surgery for genital prolapse by surgical route. A randomized controlled trial

International Urogynecology Journal (2022)

-

Turkish day-to-day impact of vaginal aging questionnaire: reliability, validity and relationship with pelvic floor distress

International Urogynecology Journal (2022)