Abstract

Ultracold polar molecules combine a rich structure of long-lived internal states with access to controllable long-range anisotropic dipole–dipole interactions. In particular, the rotational states of polar molecules confined in optical tweezers or optical lattices may be used to encode interacting qubits for quantum computation or pseudo-spins for simulating quantum magnetism. As with all quantum platforms, the engineering of robust coherent superpositions of states is vital. However, for optically trapped molecules, the coherence time between rotational states is typically limited by inhomogeneous differential light shifts. Here we demonstrate a rotationally magic optical trap for 87Rb133Cs molecules that supports a Ramsey coherence time of 0.78(4) s in the absence of dipole–dipole interactions. This is estimated to extend to >1.4 s at the 95% confidence level using a single spin-echo pulse. In our trap, dipolar interactions become the dominant mechanism by which Ramsey contrast is lost for superpositions that generate oscillating dipoles. By changing the states forming the superposition, we tune the effective dipole moment and show that the coherence time is inversely proportional to the strength of the dipolar interaction. Our work unlocks the full potential of the rotational degree of freedom in molecules for quantum computation and quantum simulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The rotational states of polar molecules, together with their controllable dipole–dipole interactions, may be used to encode and entangle qubits1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, qudits10, pseudo-spins11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 or synthetic dimensions20,21,22,23. To date, this capability has been exploited to study spin-1/2 XY models in a range of geometries24,25,26,27,28 and to engineer iSWAP gates that prepare pairs of tweezer-confined molecules in maximally entangled Bell states25,26. Such experiments rely on the precise control of molecule position that comes from using optical lattices and tweezer arrays. However, spatially varying and state-dependent light shifts in these traps generally produce a dominant source of decoherence, severely restricting the duration of coherent quantum dynamics.

‘Magic-wavelength’ traps have been invaluable in engineering atomic29 and molecular30,31 clocks that are insensitive to light shifts. The general method is to choose a wavelength where the polarizabilities of the target states are identical. For ultracold molecules, second-scale coherences have been observed between hyperfine states32,33,34, but achieving long coherence for rotational states in ultracold molecules has proved difficult due to anisotropic interactions with the trap light. The resulting differential light shifts cause the transition frequency to vary across the trap. The only implementation of a magic-wavelength trap for rotational transitions has been in 23Na40K molecules35. Here, coherence was limited to ~1 ms by inhomogeneities in the d.c. electric field that was required to decouple the rotational and nuclear angular momenta in the presence of a substantial anisotropic polarizability. Recent experiments using 23Na87Rb in near-magic optical lattices have reported single-particle rotational coherence times of 56(2) ms (ref. 28). Other attempts to produce rotationally magic traps have sought to match polarizabilities by tuning either the polarization36,37,38,39,40 or intensity41 of the light. Here, however, residual differential light shifts may still occur due to hyperfine couplings that are quadratic in intensity42. Microwave pulse sequences can be designed to minimize the effects of single-particle dephasing resulting from small residual light shifts or electric field inhomogeneity. Most notably spin-echo24,38 or XY8 (refs. 25,27) sequences have been used. To date, the longest rotational coherence time reported without rephasing is 93(7) ms for single CaF molecules in optical tweezers with a magic polarization; this was extended to 470(40) ms using a spin-echo sequence39.

In this paper, we report second-scale rotational coherence times in optically trapped 87Rb133Cs molecules (hereafter RbCs). We engineered a magic-wavelength trap by tuning the frequency of the trap light between nominally forbidden molecular transitions. We observed a rotational coherence time of \({T}_{2}^{* }=0.78(4)\) s without rephasing, limited primarily by the stability of the trap laser frequency, in a state configuration without dipole–dipole interactions. By introducing a single spin-echo pulse, we observed no loss of coherence over 0.7 s and estimated a minimum coherence time of T2 > 1.4 s at the 95% confidence level. Under these conditions, dipolar interactions became the dominant source of decoherence for superpositions that generate oscillating dipoles. We controlled the strength of these interactions by changing the states forming the superposition and demonstrated that the coherence time is inversely proportional to the strength of the dipole–dipole interactions.

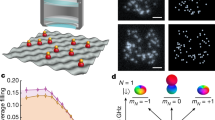

We started by preparing a thermal gas of ultracold RbCs molecules in their ground state in an optical trap (Methods). We produced ~2,400 molecules at a temperature of 1.5 μK and a peak density of 6 × 1010 cm−3. We used resonant microwaves that couple to the molecular frame dipole moment d0 = 1.23 D (ref. 43) to transfer the molecules between the rotational states shown in Fig. 1a. We labelled the states by \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \equiv (N=0,{M}_{N}=0)\), \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle \equiv (1,0)\), \(\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle \equiv (1,1)\), \(\left\vert \bar{2}\right\rangle \equiv (2,-1)\) and \(\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle \equiv (2,2)\). Here, N describes the rotational angular momentum, and MN denotes the dominant projection along the quantization axis. All of these states have dominant nuclear spin projections mRb = 3/2 and mCs = 7/2 (Supplementary Information section I).

a, Relevant rotational states in this work labelled by (N, MN). Wavefunctions for each state are shown with phase information for the states used in this work represented by the colour. b, Electronic structure of RbCs, with the energy corresponding to the 1,145 nm wavelength of the trap laser indicated by the vertical black arrow. c, By tuning the laser frequency between the transitions to \({v}^{{\prime} }=0\) and \({v}^{{\prime} }=1\) vibrational levels of the b3Π potential, we vary only the component of the polarizability parallel to the internuclear axis of the molecule α∥ whilst keeping the perpendicular component α⊥ constant. d, Polarizability for states \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\), for light polarized perpendicular to the quantization axis, as a function of laser detuning from the transition to \({{{b}}}^{3}\Pi ({v}^{{\prime} }=0)\). At a detuning of 0.186 THz, the trap is rotationally magic, and the polarizability for both states is the same. e, Schematic of the relative trap potential for laser detunings such that (i) \({\alpha }_{\left\vert 1\right\rangle } < {\alpha }_{\left\vert 0\right\rangle }\), (ii) \({\alpha }_{\left\vert 1\right\rangle }={\alpha }_{\left\vert 0\right\rangle }\) and (iii) \({\alpha }_{\left\vert 1\right\rangle } > {\alpha }_{\left\vert 0\right\rangle }\).

Optical trapping relies upon light with intensity I interacting with the dynamic polarizability of the molecule α, resulting in an energy perturbation −αI/(2ϵ0c), where ϵ0 is the permittivity of free space and c is the speed of light. In general, the polarizability along the internuclear axis, α∥, is different from that perpendicular, α⊥, with these components arising from different electronic transitions44,45. This results in a polarizability that depends on the orientation of the molecule and can be separated into isotropic α(0) and anisotropic α(2) components such that \(\alpha (\theta )={\alpha }^{(0)}+{\alpha }^{(2)}(3{\cos }^{2}\theta -1)/2\). Here, θ is the angle of the laser polarization with respect to the internuclear axis, α(0) = (α∥ + 2α⊥)/3 and α(2) = 2(α∥ − α⊥)/3. The anisotropic component leads to light shifts that depend on N, MN and the angle between the laser polarization and the quantization axis46.

To produce a rotationally magic trap, we tuned the value of α(2) to zero. We trapped using 1,145 nm wavelength light tuned between the transitions to the \({v}^{{\prime} }=0\) and \({v}^{{\prime} }=1\) vibrational states of the mixed b3Π potential, as indicated in Fig. 1b, following the scheme proposed by Guan et al.47. Transitions to this potential are nominally forbidden from the X1Σ+ ground state but may be driven due to weak mixing of b3Π with the nearby A1Σ+ potential. Coupling to A1Σ+ components allows α∥ to be tuned by varying the frequency of the light, with poles in the polarizability occurring for each vibrational state in the b3Π potential, as shown in Fig. 1c. Meanwhile, α⊥ remains nearly constant as the light is red detuned by ~100 THz from the bottom of the nearest 1Π potential. By setting α∥ = α⊥ with the laser frequency, the polarizability of the molecule becomes isotropic such that α(2) = 0 and α(0) = α⊥. In Fig. 1d,e, we show the effect of tuning the laser frequency for molecules in \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\). The magic condition where the polarizability, and therefore the trap potential, is the same occurs at a detuning of ~186 GHz from the transition to the \({v}^{{\prime} }=0\) state. As the anisotropic polarizability is near zero around this detuning, the light is nearly magic for many rotational states simultaneously47.

To experimentally identify the magic detuning, we performed Ramsey interferometry, as shown schematically in Fig. 2a. In the example shown, a π/2 pulse first prepares the molecules in an equal superposition of states \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\). This is then allowed to evolve freely for a time T, during which the Bloch vector precesses around the equator at a rate proportional to the detuning of the microwaves from resonance. Finally, a second π/2 pulse with variable phase Φ is used to project back onto the state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) for detection. For a given pair of states, we fixed the Ramsey time and measured the contrast of Ramsey fringes as a function of the laser detuning (Methods). We observed maximum fringe contrast when the trap light was tuned to magic, as shown in Fig. 2, indicating that the coherence time for that combination of states has been maximized. There is a small ~1 GHz variation in the magic detuning that depends on the states chosen; this is due to coupling to different rotational levels of the excited vibrational states47. The width of the feature depends on the sensitivity of the light shifts to the laser frequency and is inversely proportional to the Ramsey time.

a, Bloch sphere representation of the Ramsey interferometry sequence. For each step, the dotted and solid red arrows represent the initial and final Bloch vectors, respectively. Solid black arrows indicate the axis about which the Bloch vector is rotated using coherent π/2 pulses performed on microwave transitions between the neighbouring rotational states. Ramsey fringes are observed as a variation in molecule number Nmol in state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) as a function of Φ. b, Fringe contrast as a function of trap laser detuning from the transition to \({{{b}}}^{3}\Pi ({v}^{{\prime} }=0)\) for state combinations and Ramsey times (i) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\), T = 20 ms; (ii) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\), T = 30 ms; and (iii) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 1\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{2}\right\rangle )\), T = 30 ms. Results for combination (iv) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle )\) are shown for Ramsey times of T = 40 ms (empty circles) and T = 175 ms (filled circles). The lines show Gaussian fits to each of the results to identify the magic detuning. c, Example of Ramsey fringes for case (i); the molecule number detected in state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) is plotted as a fraction of the total number \({N}_{{{{\rm{mol}}}}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}\) for various detunings given relative to the magic condition. Error bars in all plots indicate 1σ standard error.

Tuning close to transitions could lead to loss of molecules due to photon scattering. However, our method is compatible with long trap lifetimes. To estimate the scattering rate from the 1,145 nm light, we examined the loss of molecules in \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) from the trap. We began measurement after a hold time in the trap of 0.4 s to lower the density of molecules and therefore reduce collisional losses48,49. We compared the loss from the magic-wavelength trap to the loss when the wavelength was changed to 1,064 nm, with the intensity set such that the molecules experience the same trap frequencies. The results are shown in Fig. 3a, with fits from a model assuming an exponential decay (Supplementary Information section II). We observed similar loss rates, corresponding to lifetimes on the order of ~1 s at either wavelength. Assuming that the photon scattering rate in the 1,064 nm trap was negligible, we estimated an upper limit on the photon scattering rate in the 1,145 nm trap of <0.23 s−1 at the 95% confidence level. We have characterized the linewidths of the relevant transitions, with the closest having linewidths \({\Gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} } = 0}=11.1(1.2)\) kHz, \({\gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} } = 0}=20(3)\) kHz and \({\Gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} } = 1}=7.2(9)\) kHz, \({\gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} } = 1}=103(15)\) kHz. Here, \({\Gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) is the transition width associated with the transition dipole moment from the ground state, and \({\gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) is the natural linewidth of the excited state determined by the rate of spontaneous decay. Therefore, the light was effectively far detuned, with the ratio of the detuning to the linewidth of the nearest transition \(\Delta /{\Gamma }_{{v}^{{\prime} } = 0}\approx 5\times 1{0}^{7}\). It follows that the loss due to photon scattering is not an issue for our magic-wavelength trap.

Molecules were prepared with an initial density of 6 × 1010 cm−3. a, Comparison of loss for molecules prepared in \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) in the magic trap (filled circles) and an equivalent trap using light with wavelength of 1,064 nm (empty stars). b, Comparison of loss from the trap for molecules prepared in either \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle\) with the superposition \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\). Exponential fits are shown for all results, and the error bars indicate 1σ standard error.

When molecules are prepared in superpositions of rotational states connected by dipole-allowed transitions, they exhibit an oscillating dipole moment in the laboratory frame. The resultant dipole–dipole interactions can significantly affect the collisional loss rate48. In Fig. 3b, we compare loss from the magic trap for molecules prepared in either \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle\), or the superposition \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\). For the dipolar superposition, we observed a loss rate that is 2.5 times greater than for molecules in either \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle {\rm{or}}\,\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle\). Therefore, the interrogation time available for dipolar samples is much shorter than for non-interacting samples.

We first measured the coherence time for a non-interacting sample of molecules by examining the coherence between \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle\); these are two states not linked by an electric dipole-allowed transition. We used a pulse sequence composed of one-photon π/2 and π pulses on the electric dipole-allowed transitions \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle\) (Supplementary Information section III). We measured the contrast of the Ramsey fringes as a function of time, normalized to the number of molecules remaining in the sample, as shown by the empty circles in Fig. 4a. We fitted the results with a Gaussian model for decoherence (Supplementary Information section IV), where the fringe contrast \(C(t)=\exp [-{(T/{T}_{2}^{* })}^{2}]\), and find a coherence time \({T}_{2}^{* }=0.78(4)\) s.

a, Fringe contrast as a function of the Ramsey time for non-interacting \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle )\) (black circles) and dipolar \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\) (blue squares) superpositions. Empty markers indicate measurements using a standard Ramsey sequence, and filled markers indicate measurements performed with the addition of a single spin-echo pulse. The non-interacting results were fitted using a Gaussian model for decoherence, and the dipolar results were fitted, assuming an exponential decay in the fringe contrast. The blue lines indicate the decay in the fringe contrast from MACE simulations, as described in the main text. Uncertainties in the fits and simulations are indicated by the shaded regions. The fringes observed for \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle )\) with spin echo at T = 0.7 s are shown inset. Spin-echo fringes are given without normalization for all Ramsey times, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3. In addition, the other inset shows the wavefunction for the dipolar superposition \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\) as a function of time (phase, ϕ). The resultant dipole (white arrow) rotates around the quantization axis (vertical black line) at a frequency proportional to the difference in energy δE between the states. b, Coherence time in the presence of dipole–dipole interactions. We plotted the 1/e coherence time measured with spin echo as a function of the effective laboratory-frame dipole moment, tuned by changing the states used in the spin-echo sequence. The combinations used were (i) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 1\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{2}\right\rangle )\), (ii) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\) and (iii) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\). The fringe contrast as a function of time for each state combination is shown in the top-right inset. The wavefunctions are illustrated with (i) and (ii) yielding dipoles rotating around the quantization axis and (iii) resulting in a dipole that oscillates up and down. The bottom-left inset shows the coherence time plotted as a function of the inverse of the dipole–dipole interaction strength ∝ 1/d2. Error bars in all plots indicate 1σ standard error in the measurements, and the 1σ uncertainties in the fits and simulations are shown by the shaded regions.

The observed coherence time was limited by residual differential a.c. Stark shifts in the trap, which resulted from small detunings from the magic wavelength. We estimated the stability of the trap laser frequency to be ±0.76 MHz (±1σ) over each fringe measurement (~30 min). This corresponds to a variation of the transition frequency of ±0.46 Hz and a limit on the coherence time of 1.1 s. There are smaller contributions to decoherence from the uncertainty in the magic wavelength extracted from the results in Fig. 2b with T = 175 ms (limit of 4.3 s) and from a 10 MHz frequency difference between the two trap beams (limit of 8.3 s). Further details are provided in Supplementary Information section V. Additionally, a small differential magnetic moment between the states of 0.0124 μN limits the coherence time to 10.6 s associated with magnetic field noise (~10 mG). Combining all contributions provides an expected limit on the coherence time of 0.74 s, in excellent agreement with our observations. Up to an order of magnitude improvement in the coherence time may be achieved by using a better method of laser frequency stabilization; for example, frequency stability below 100 kHz can be achieved by referencing to a high-finesse optical cavity50.

We removed most of these decoherence effects by introducing a single spin-echo pulse halfway through the Ramsey time; this is an effective π pulse between \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \hat{2}\right\rangle\) that reverses the direction of precession around the Bloch sphere, thereby cancelling out single-particle dephasing from static inhomogeneities. Figure 4 displays the result, as indicated by the filled circles. We observed no loss of fringe contrast over 0.7 s. We did not measure for longer times, as molecule loss diminishes the signal-to-noise ratio. For all the measurements, at least 500 molecules were detected at the maximum of the Ramsey fringe. The phase of the fringe changes with Ramsey time (Supplementary Fig. 4). This does not lead to any appreciable loss of coherence, although it would indicate a time-varying shift in the energies of the states that causes a different phase to accrue over the two halves of the spin-echo sequence. We fitted our results using the Gaussian model, with confidence intervals defined using the approach of Feldman and Cousins51 to estimate a minimum coherence time consistent with our results to be T2 > 1.4 s at the 95% confidence level. This represents the suppression of all decoherences at the detectable precision of our experiment.

For superpositions of states that lead to oscillating dipoles, dipolar interactions also cause dynamics of the Ramsey fringe contrast, and therefore introduce an additional source of decoherence. The dipole–dipole interactions in the system are described by the Hamiltonian15,16,52

where \({\hat{d}}_{0},\hat{{d}_{1}},\hat{{d}_{-1}}\) are spherical components of the dipole operator, Θij is the angle between the vector connecting two molecules and the quantization axis, and rij is the intermolecular distance. The local spatial configuration of molecules varies across the sample. Moreover, as the molecules are not pinned by an optical lattice, their configuration is time dependent due to motion of the molecules around the trap.

We examined the coherence between \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle\). An equal superposition of these states produces a dipole that rotates around the quantization axis, with a magnitude given by the transition dipole moment \({d}_{0}/\sqrt{3}\). However, due to the factor of 2 in the denominator of the final term of equation (1), this contributes an effective dipole \(d={d}_{0}/\sqrt{6}=0.5\) D in the laboratory frame. At the peak densities in our experiments, this corresponded to an interaction strength of ~h × 2 Hz. The blue squares in Fig. 4a represent the fringe contrast measured as a function of time, both with (filled) and without (empty) a spin-echo pulse. We observed a dramatic reduction in the coherence time measured using either sequence compared to the non-interacting case. Moreover, the results were no longer well described by the Gaussian model. Instead, we fitted the results assuming an exponential decay of fringe contrast \(C(t)=\exp (-T/{T}_{2}^{{{{\rm{DDI}}}}})\) (Supplementary Information section IV). We found a 1/e coherence time of 89(5) ms without spin echo and \({T}_{2}^{{{{\rm{DDI}}}}}\) = 157(14) ms with spin echo. The residual a.c. Stark shifts that affect the results without spin echo vary depending on the combination of states. We expected that the uncertainty in the magic detuning is dominant for this dipolar combination because collisional losses and dipolar decoherence limit the Ramsey time used during the optimization. However, the difference in coherence time between dipolar and non-interacting samples that was observed with the spin-echo pulse can be attributed to dipole–dipole interactions alone.

We tuned the strength of the dipole–dipole interactions by using different state superpositions. In Fig. 4b, we show the coherence time measured with spin echo as the effective dipole moment was varied from 0.31 to 0.65 D. The laser frequency was set to maximize the coherence time for each state combination. As expected, we observed that the coherence time was inversely proportional to the magnitude of the interaction strength Uij ∝ d2, which confirms that dipolar interactions are dominant. Moreover, this demonstrates the application of our magic-wavelength trap to molecules in a range of states, which allows control over the interactions.

We compared the observed decay of the fringe contrast to that calculated using the moving-average cluster expansion (MACE) method53 for molecules fixed in space (Methods). Losses are included in the theory by assuming that molecules are lost at a constant rate independent of other molecules. We included the loss in the MACE calculations using a 1/e loss time of 0.14(5) s, determined from the exponential fit to the experimental results shown as open blue squares in Fig. 3b. We measured similar loss rates for all three dipolar combinations investigated. Decreases in density from loss noticeably slowed down the dynamics, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a. Without fitting, using only the measured loss rates, densities and trap parameters, the MACE calculations reproduced the timescale for the decay in the Ramsey fringe contrast, as well as the dependence on the choice of state pair, and the overall monotonic decrease. The result for \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\) is shown in Fig. 4a. Some details differ, most noticeably that the MACE results predicted modestly but systematically shorter timescales and a more concave dependence on time than the experimental results. The theory contrast is between the measured echo and no-echo contrast, and differs from the echo results by roughly the same factor for all state-pair choices, suggesting a common underlying cause. Molecule motion during the dynamics is a likely source. The reasonably good agreement between the MACE calculations and experiment for the overall timescale of contrast decay, and the dependence of this timescale on the strength of the dipole–dipole interactions, supports the conclusion that dipole–dipole interactions are the main cause of the contrast decay for state combinations that generate oscillating dipoles.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a rotationally magic trap for RbCs molecules, where all experimentally relevant sources of decoherence were suppressed, resulting in a coherence time in excess of 1.4 s for non-interacting rotational superpositions. Crucially, the magic wavelength is sufficiently far detuned from transitions that we observed negligible photon scattering rates and hence long trap lifetimes, and does not require the application of a d.c. electric field (Supplementary Information section VI). This provides unparalleled access to controllable dipole–dipole interactions between molecules. Our approach of trapping using light detuned from the nominally forbidden \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{1}\Sigma (v=0)\to {{{{{b}}}}}^{3}\Pi ({v}^{{\prime} }=0)\) transition may be applicable to some other bi-alkali molecules, such as NaRb (ref. 47).

Our work enables the construction of low-decoherence networks of rotational states, which are the foundation for many future applications of ultracold molecules from quantum computation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,10 and simulation11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 to precision measurement54. The next step will be to construct molecular arrays using light at this magic wavelength. For molecules in optical tweezers, this will enable high-fidelity quantum gates using resonant dipolar exchange, either directly between molecules25,26 or mediated via Rydberg atoms7,8,55. For a 20 μK deep tweezer, we predict a photon scattering rate of 0.18 s−1 leading to a lifetime greater than 1 s. For molecules in optical lattices, long rotational coherence times can be combined with long lifetimes. For a lattice depth of 20 recoil energies, we predict a one-photon scattering rate of 0.006 s−1, corresponding to a lifetime in excess of 100 s. In the magic-wavelength lattice, nearest neighbours will experience an interaction strength of h × 343 Hz for the largest effective dipoles explored here (and Θ = π/2). The timescale for dipolar spin-exchange dynamics is therefore 2.9 ms, far shorter than the coherence time and the lifetime. Techniques for producing ordered lattice arrays of RbCs molecules have been demonstrated56,57 and are compatible with a magic-wavelength lattice. Therefore, our work unlocks the potential of ultracold molecules in optical lattices for simulating quantum magnetism.

Methods

Production of ground-state molecules

We produced ultracold RbCs molecules from a precooled mixture of Rb and Cs atoms. The atomic mixture was confined to a crossed optical dipole trap using light with a wavelength of 1,550 nm, and a magnetic field gradient was applied to cancel the force due to gravity58. To form molecules, we swept the magnetic field down across an interspecies Feshbach resonance at 197 G (ref. 59). We then removed the remaining atoms from the trap by increasing the magnetic field gradient to over-levitate the atoms, following which the magnetic field gradient was removed. With the exception of the measurements shown in Fig. 3a, at this point, the molecules were transferred to the magic trap by ramping the power in the 1,145 nm light for over 30 ms, and then the power in the 1,550 nm trap off over a further 5 ms. Finally, we transferred the molecules to the X1Σ ground state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) using a stimulated Raman adiabatic passage43,60. This final step was performed with the trap light briefly turned off to avoid spatially varying a.c. Stark shifts of the transitions. For the measurements in Fig. 3a, we increased the power in the 1,550 nm trap after the removal of atoms and transferred to the magic trap following the ground-state transfer. Throughout all of the measurements shown, the molecules were subjected to a fixed 181.5 G magnetic field, and there was no electric field. To detect molecules in \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\), we reversed the association process, breaking the molecules back apart into their constituent atoms, which we detected using absorption imaging.

Details of the magic trap

The magic trap was formed from two beams, each with a waist of 50 μm. The beams crossed at an angle of 20°, which was chosen to be close to the 27° crossing angle of the 1,550 nm trap without requiring overlapping of the 1,145 and 1,550 nm light. The beams propagated and were polarized in the plane orthogonal to the applied magnetic field that defined the quantization axis. Both beams were derived from the same laser (a vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting laser from Vexlum), and to avoid interference effects, we set a 10 MHz difference in frequency between the beams. This was implemented using acousto-optic modulators, which were also used to switch the trap beams on and off. The laser detuning shown in Fig. 2b,c was the average detuning of the two beams. The intensities of the beams were not actively stabilized but were monitored to ensure that they were passively stable to <5% variation over the course of each measurement. The typical trap frequencies experienced by ground-state molecules at the magic detuning were [ωx, ωy, ωz] = [29(1), 144(5), 147(5)] Hz for a peak laser intensity of 14 kW cm−2. After 15 ms in the magic trap, we estimated the temperature of the ground-state molecules to be 1.5(2) μK by observing the time-of-flight expansion of the molecules over 6 ms following stimulated Raman adiabatic passage back to the Feshbach state.

The frequency of the 1,145 nm laser was stabilized using a scanning transfer cavity lock61, which was referenced to a 977 nm laser that was in turn locked to a high-finesse cavity with an ultralow expansion glass spacer50. The lock corrected the laser frequency at a rate of ~100 Hz. This slow feedback rate, together with the relatively low finesse of the transfer cavity ~400, limited the frequency stability of the laser in the current experiments.

Coherent state control

We used coherent one-photon microwave pulses to perform the Ramsey interferometry, during which the trap light was turned off. The microwave sources were referenced to a 10 MHz global positioning system clock. We set the microwaves in resonance with the desired transition and calibrated the duration of the pulses using one-photon spectroscopy (described in ref. 62). The pulse sequences used in this study are shown schematically in Supplementary Information section II.

Analysis of Ramsey fringes

We observed Ramsey fringes as a variation in the molecule number Nmol detected in state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) as a function of the phase difference Φ between the initialization and readout microwave pulses. We fitted each measurement with the function

where \({N}_{{{{\rm{mol}}}}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}\) is the total number of molecules in the sample, Φ0 is the phase offset in the Ramsey fringe and C is the contrast.

We used a bootstrap fitting algorithm63 to estimate the uncertainty in the fringe contrast. For a given fringe measurement, we randomly sampled the measured Nmol for each value of Φ to build a new dataset of the same size as the original. We fitted these randomly resampled data to extract a coherence time. This process was repeated 1,000 times to build a distribution of fitted coherence times, from which we calculated a standard deviation that represents the uncertainty in the true value. As the fringe contrast must be between 0 and 1, we constructed confidence intervals for each result using the approach of Feldman and Cousins51. This yielded asymmetric error bars for fringe contrasts close to 1.

Moving-average cluster expansion

We calculated the dynamics of our system using the MACE method53. Particle locations were randomly sampled from the thermal distribution based on the measured trap parameters, temperature and particle number, and were assumed to be fixed for all times at their initial positions. We calculated the dynamics starting from all molecules in the \(\left\vert \to \right\rangle\) state, which is the state (ideally) prepared by the initial π/2 pulse in the Ramsey spectroscopy sequence. We simulated the time evolution of the Hamiltonian in equation (1) projected onto the relevant state pair, which is a spin-1/2 dipolar XX model15,16

where \({\bf{r}}_{ij}={\bf{r}}_{i}-{\bf{r}}_{j}\) is the distance between molecules i and j, θij is the angle between the quantization axis and \({\bf{r}}_{ij}\), \({S}_{i}^{\pm }\) are raising/lowering operators, \({J}_{\perp }=-{\langle \uparrow | {d}_{1}| \downarrow \rangle }^{2}\) for state pairs with angular momentum projections differing by ±1 and \({J}_{\perp }=2{\langle \uparrow | {d}_{0}| \downarrow \rangle }^{2}\) for state pairs with the same angular momentum projection. For the \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert \bar{1}\right\rangle )\) state pair, \(| \frac{{J}_{\perp }\rho }{2h}| =2.26\,{{{\rm{Hz}}}}\), where ρ is the estimated peak density (6 × 1010 cm−3). Each simulation was performed to a time just before the second π/2 pulse, and then the expectation of \({S}^{x}={\sum }_{i}{S}_{i}^{x}\) was calculated, which was the same as the Ramsey contrast after the pulse. The MACE method constructed a cluster for each \({S}_{i}^{x}\) from molecule i and the Nc − 1 other molecules with the strongest interactions with atom i, where Nc is a convergence parameter of the method. We exactly calculated \(\langle {S}_{i}^{x}(t)\rangle\) of each resulting cluster. To assess convergence, we compared the dynamics for Nc = 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The results converged quickly with Nc for the simulation times of interest, and Nc = 6 was used for the results in Fig. 4. The contrast is expected to be converged within widths of the plotted lines over most of the time regime shown.

The dynamics of the Ramsey contrast is already roughly captured if one ignores particle loss, but the loss has non-negligible quantitative effects, which we have included in our calculations shown in the main text. Molecules leaving the trap decrease the density, which causes the contrast to decay more slowly. To include this loss in the MACE calculations, we assumed that molecules were independently lost from the trap at a constant rate, which is consistent with the measured time dependence of the particle number. We experimentally determined the loss rate to be 0.14(5) s. MACE clusters were built based on the particle distribution at time t = 0 and did not change over time. For each cluster, whenever a molecule was lost, we set the interactions between the lost molecule and the remaining molecules to zero. To propagate the dynamics after this event, we re-diagonalized the Hamiltonian. This modestly increased the computational difficulty but only by a factor of Nc in the worst case (when all molecules were lost during the timescale under consideration). To obtain good statistics, we averaged together 10 loss trajectories of ~2,400 molecules each to obtain a stable result. This reduced the statistical error between runs to a maximum of 2% over the timescales we were working with.

The error bars in the theoretical calculations presented in the main text show the result of the experimental uncertainty in the number of molecules, loss rate and temperature. For particle number uncertainty, we computed the Ramsey contrast decay for the ±1σ measured particle numbers and did the same for the loss rate uncertainty and temperature uncertainty. These uncertainties were added together in quadrature to obtain the error bounds shown in Fig. 4. Each of these errors is much larger than the statistical or MACE convergence errors.

Data availability

The data associated with this work are available at https://doi.org/10.15128/r19593tv218.

References

DeMille, D. Quantum computation with trapped polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 067901 (2002).

Yelin, S. F., Kirby, K. & Côte, R. Schemes for robust quantum computation with polar molecules. Phys. Rev. A 74, 050301(R) (2006).

Pellegrini, P. & Desouter-Lecomte, M. Quantum gates driven by microwave pulses in hyperfine levels of ultracold heteronuclear dimers. Eur. Phys. J. D 64, 163 (2011).

Wei, Q., Cao, Y., Kais, S. & Friedrich, B. Quantum computation using arrays of N polar molecules in pendular states. ChemPhysChem 17, 3714 (2016).

Ni, K.-K., Rosenband, T. & Grimes, D. D. Dipolar exchange quantum logic gate with polar molecules. Chem. Sci. 9, 6830 (2018).

Hughes, M. et al. Robust entangling gate for polar molecules using magnetic and microwave fields. Phys. Rev. A 101, 062308 (2020).

Zhang, C. & Tarbutt, M. R. Quantum computation in a hybrid array of molecules and Rydberg atoms. PRX Quantum 3, 030340 (2022).

Wang, K., Williams, C. P., Picard, L. R., Yao, N. Y. & Ni, K.-K. Enriching the quantum toolbox of ultracold molecules with Rydberg atoms. PRX Quantum 3, 030339 (2022).

Asnaashari, K., Krems, R. V. & Tscherbul, T. V. General classification of qubit encodings in ultracold diatomic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 6593–6602 (2023).

Sawant, R. et al. Ultracold polar molecules as qudits. New J. Phys. 22, 013027 (2020).

Barnett, R., Petrov, D., Lukin, M. & Demler, E. Quantum magnetism with multicomponent dipolar molecules in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 190401 (2006).

Micheli, A., Brennen, G. K. & Zoller, P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 2, 341 (2006).

Capogrosso-Sansone, B., Trefzger, C., Lewenstein, M., Zoller, P. & Pupillo, G. Quantum phases of cold polar molecules in 2D optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 125301 (2010).

Pollet, L., Picon, J. D., Büchler, H. P. & Troyer, M. Supersolid phase with cold polar molecules on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 125302 (2010).

Gorshkov, A. V. et al. Tunable superfluidity and quantum magnetism with ultracold polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 115301 (2011).

Gorshkov, A. V. et al. Quantum magnetism with polar alkali-metal dimers. Phys. Rev. A 84, 033619 (2011).

Zhou, Y. L., Ortner, M. & Rabl, P. Long-range and frustrated spin-spin interactions in crystals of cold polar molecules. Phys. Rev. A 84, 052332 (2011).

Hazzard, K. R. A., Manmana, S. R., Foss-Feig, M. & Rey, A. M. Far-from-equilibrium quantum magnetism with ultracold polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 075301 (2013).

Lechner, W. & Zoller, P. From classical to quantum glasses with ultracold polar molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185306 (2013).

Sundar, B., Gadway, B. & Hazzard, K. R. A. Synthetic dimensions in ultracold polar molecules. Sci. Rep. 8, 3422 (2018).

Sundar, B., Thibodeau, M., Wang, Z., Gadway, B. & Hazzard, K. R. A. Strings of ultracold molecules in a synthetic dimension. Phys. Rev. A 99, 013624 (2019).

Feng, C., Manetsch, H., Rousseau, V. G., Hazzard, K. R. A. & Scalettar, R. Quantum membrane phases in synthetic lattices of cold molecules or Rydberg atoms. Phys. Rev. A 105, 063320 (2022).

Cohen, M., Casebolt, M., Zhang, Y., Hazzard, K. R. A. & Scalettar, R. Classical analog of quantum models in synthetic dimensions. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.07017 (2022).

Yan, B. et al. Observation of dipolar spin-exchange interactions with lattice-confined polar molecules. Nature 501, 521 (2013).

Bao, Y. et al. Dipolar spin-exchange and entanglement between molecules in an optical tweezer array. Prepint at ArXix:2211.09780 (2022).

Holland, C. M., Lu, Y. & Cheuk, L. W. On-demand entanglement of molecules in a reconfigurable optical tweezer array. Preprint at ArXiv:2210.06309 (2022).

Li, J.-R. et al. Tunable itinerant spin dynamics with polar molecules. Nature 614, 70 (2023).

Christakis, L. et al. Probing site-resolved correlations in a spin system of ultracold molecules. Nature 614, 64 (2023).

Takamoto, M., Hong, F.-L., Higashi, R. & Katori, K. An optical lattice clock. Nature 435, 321 (2005).

Kondov, S. S. et al. Molecular lattice clock with long vibrational coherence. Nat. Phys. 15, 1118 (2019).

Leung, K. H. et al. Terahertz vibrational molecular clock with systematic uncertainty at the 10−14 level. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011047 (2023).

Park, J. W., Yan, Z. Z., Loh, H., Will, S. A. & Zwierlein, M. W. Second-scale nuclear spin coherence time of ultracold 23Na40K molecules. Science 357, 372 (2017).

Gregory, P. D., Blackmore, J. A., Bromley, S. L., Hutson, J. M. & Cornish, S. L. Robust storage qubits in ultracold polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 17, 1149 (2021).

Lin, J., He, J., Jin, M., Chen, G. & Wang, D. Seconds-scale coherence on nuclear spin transitions of ultracold polar molecules in 3D optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 223201 (2022).

Bause, R. et al. Tune-out and magic wavelengths for ground state 23Na40K molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 023201 (2020).

Kotochigova, S. & DeMille, D. Electric-field-dependent dynamic polarizability and state-insensitive conditions for optical trapping of diatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. A 82, 063421 (2010).

Neyenhuis, B. et al. Anisotropic polarizability of ultracold polar 40K87Rb molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 230403 (2012).

Seeßelberg, F. et al. Extending rotational coherence of interacting polar molecules in a spin-decoupled magic trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 253401 (2018).

Burchesky, S. et al. Rotational coherence times of polar molecules in optical tweezers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 123202 (2021).

Tobias, W. G. et al. Reactions between layer-resolved molecules mediated by dipolar spin exchange. Science 375, 1299 (2022).

Blackmore, J. A. et al. Ultracold molecules for quantum simulation: rotational coherences in CaF and RbCs. Quan. Sci. Technol. 4, 014010 (2018).

Blackmore, J. A. et al. Controlling the ac stark effect of RbCs with dc electric and magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. A 102, 053316 (2020).

Molony, P. K. et al. Creation of ultracold 87Rb133Cs molecules in the rovibrational ground state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 255301 (2014).

Kotochigova, S. & Tiesinga, E. Controlling polar molecules in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 73, 041405(R) (2006).

Vexiau, R. et al. Dynamic dipole polarizabilities of heteronuclear alkali dimers: optical response, trapping and control of ultracold molecules. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 36, 709 (2017).

Gregory, P. D., Blackmore, J. A., Aldegunde, J., Hutson, J. M. & Cornish, S. L. ac Stark effect in ultracold polar 87Rb133Cs molecules. Phys. Rev. A 96, 021402(R) (2017).

Guan, Q., Cornish, S. L. & Kotochigova, S. Magic conditions for multiple rotational states of bialkali molecules in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 103, 043311 (2021).

Gregory, P. D. et al. Sticky collisions of ultracold RbCs molecules. Nat. Commun. 10, 3104 (2019).

Gregory, P. D., Blackmore, J. A., Bromley, S. L. & Cornish, S. L. Loss of ultracold 87Rb133Cs molecules via optical excitation of long-lived two-body collision complexes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 163402 (2020).

Gregory, P. D. et al. A simple, versatile laser system for the creation of ultracold ground state molecules. New J. Phys. 17, 055006 (2015).

Feldman, G. J. & Cousins, R. D. Unified approach to the classical statistical analysis of small signals. Phys. Rev. D 57, 3873 (1998).

Wall, M. L., Hazzard, K. R. A. & Rey, A. M. in From Atomic to Mesoscale (eds Malinovskaya, S. A. & Novikova, I.) Ch. 1 (World Scientific, 2015).

Hazzard, K. R. A. et al. Many-body dynamics of dipolar molecules in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 195302 (2014).

Kłos, J., Li, H., Tiesinga, E. & Kotochigova, S. Prospects for assembling ultracold radioactive molecules from laser-cooled atoms. New J. Phys. 24, 025005 (2022).

Guttridge, A. et al. Observation of Rydberg blockade due to the charge-dipole interaction between an atom and a polar molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 013401 (2023).

Reichsöllner, L., Schindewolf, A., Takekoshi, T., Grimm, R. & Nägerl, H.-C. Quantum engineering of a low-entropy gas of heteronuclear bosonic moleucles in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 073201 (2017).

Das, A. et al. An association sequence suitable for producing ground-state RbCs molecules in optical lattices. Preprint at ArXiv:2303.16144 (2023).

McCarron, D. J., Cho, H. W., Jenkin, D. L., Köppinger, M. P. & Cornish, S. L. Dual-species Bose-Einstein condensate of 87Rb133Cs. Phys. Rev. A 84, 011603(R) (2011).

Köppinger, M. P. et al. Production of optically trapped 87RbCs Feshbach molecules. Phys. Rev. A 89, 033604 (2014).

Molony, P. K. et al. Production of ultracold 87Rb133Cs in the absolute ground state: complete characterisation of the STIRAP transfer. ChemPhysChem. 17, 3811 (2016).

Subhankar, S., Restelli, A., Wang, Y., Rolston, S. L. & Porto, J. V. Microcontroller based scanning transfer cavity lock for long-term laser frequency stabilisation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 90, 043115 (2019).

Gregory, P. D., Aldegunde, J., Hutson, J. M. & Cornish, S. L. Controlling the rotational and hyperfine state of ultracold 87Rb133Cs molecules. Phys. Rev. A 94, 041403(R) (2016).

Efron, B. & Tibshirani, R. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat. Sci. 1, 54 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. M. Hutson for many insightful discussions, and S. Ospelkaus and M. Tarbutt for the loan of tapered amplifiers used in the early stages of this project. The work of the authors from Durham University was supported by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Grants EP/P01058X/1, EP/P008275/1 and EP/W00299X/1; UK Research and Innovation Frontier Research Grant EP/X023354/1; and Royal Society and Durham University. K.R.A.H. acknowledges support from the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1872), National Science Foundation (NSF) (PHY-1848304), Office of Naval Research (N00014-20-1-2695) and W.M. Keck Foundation (Grant No. 995764). The work of S.K. was supported by the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant Nos. FA9550-21-1-0153 and FA9550-19-1-0272, and NSF Grant No. PHY-1908634.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiments were performed by P.D.G., L.M.F., A.L.T. and S.L.B. under the supervision of S.L.C. S.K. developed the magic trap scheme and provided a theory relating to the 1,145 nm transitions in RbCs. J.S., Z.Z. and K.R.A.H. performed the MACE calculations and provided a theory relating to dipolar interactions in the gas.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information I–VI

Supplementary sections I–VI and Figs. 1–5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gregory, P.D., Fernley, L.M., Tao, A.L. et al. Second-scale rotational coherence and dipolar interactions in a gas of ultracold polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 20, 415–421 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02328-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02328-5