Abstract

Mechanisms governing the relationship between genetic and cultural evolution are the subject of debate, data analysis and modelling efforts. Here we present a new georeferenced dataset of personal ornaments worn by European hunter-gatherers during the so-called Gravettian technocomplex (34,000–24,000 years ago), analyse it with multivariate and geospatial statistics, model the impact of distance on cultural diversity and contrast the outcome of our analyses with up-to-date palaeogenetic data. We demonstrate that Gravettian ornament variability cannot be explained solely by isolation-by-distance. Analysis of Gravettian ornaments identified nine geographically discrete cultural entities across Europe. While broadly in agreement with palaeogenetic data, our results highlight a more complex pattern, with cultural entities located in areas not yet sampled by palaeogenetics and distinctive entities in regions inhabited by populations of similar genetic ancestry. Integrating personal ornament and biological data from other Palaeolithic cultures will elucidate the complex narrative of population dynamics of Upper Palaeolithic Europe.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used for the statistical tests can be found in the Supplementary tables.

Code availability

Code used is available from the corresponding author upon request and is detailed in the Supplementary Information.

References

Jordan, P. Technology as Human Social Tradition: Cultural Transmission Among Hunter-Gatherers Vol. 7 (Univ. California Press, 2014).

O’Brien, M. J. & Lyman, R. L. Evolutionary archeology: current status and future prospects. Evol. Anthropol. 11, 26–36 (2002).

Pettitt, P. The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial (Routledge, 2013).

Bar-Yosef, O. & Kuhn, S. L. The big deal about blades: laminar technologies and human evolution. Am. Anthropol. 101, 322–338 (1999).

Bon, F. At the crossroad. Palethnol. Archéol. Sci. Hum. https://doi.org/10.4000/palethnologie.680 (2015).

Kuhn, S. L. et al. The early upper paleolithic occupations at Üçağızlı cave (Hatay, Turkey). J. Hum. Evol. 56, 87–113 (2009).

Bennett, E. A. et al. The origin of the Gravettians: genomic evidence from a 36,000-year-old Eastern European. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/685404 (2019).

Fu, Q. et al. The genetic history of ice age Europe. Nature 534, 200–205 (2016).

Posth, C. et al. Paleogenomics of upper paleolithic to neolithic European hunter-gatherers. Nature 615, 117–126 (2023).

Villalba-Mouco, V. et al. A 23,000-year-old southern Iberian individual links human groups that lived in Western Europe before and after the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 597–609 (2023).

Eisenmann, S. et al. Reconciling material cultures in archaeology with genetic data: the nomenclature of clusters emerging from archaeogenomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 13003 (2018).

Riede, F. in Investigating Archaeological Cultures: Material Culture, Variability, and Transmission (eds Roberts, B. W. & Vander Linden, M.) 245–270 (Springer, 2011).

Riede, F., Hoggard, C. & Shennan, S. Reconciling material cultures in archaeology with genetic data requires robust cultural evolutionary taxonomies. Palgrave Commun. 5, 55 (2019).

Joyce, R. A. Archaeology of the body. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 34, 139–158 (2005).

Plog, S. E. & Richman, K. Symbols in action: ethnoarchaeological studies of material culture. Ian Hodder. Am. Anthropol. 85, 718–720 (1983).

Alvarez-Fernandez, E. Los Objetos de Adorno-colgantes del Paleolítico Superior y del Mesolítico en la Cornisa Cantábrica y en el Valle Del Ebro: Una Visión Europea (Univ. Salamanca, 2006).

Rigaud, S., Manen, C. & García-Martínez de Lagrán, I. Symbols in motion: flexible cultural boundaries and the fast spread of the Neolithic in the western Mediterranean. PLoS ONE 13, p.e0196488 (2018).

Rigaud, S., d’Errico, F. & Vanhaeren, M. Ornaments reveal resistance of North European cultures to the spread of farming. PLoS ONE 10, e0121166 (2015).

Sehasseh, E. M. et al. Early middle stone age personal ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi8620 (2021).

Vanhaeren, M. & d’Errico, F. Aurignacian ethno-linguistic geography of Europe revealed by personal ornaments. J. Anthropol. Sci. 33, 1105–1128 (2006).

Aubry, T., Santos, A. T. & Martins, A. Côa Symposium. Novos olhares sobre a arte paleolítica. New perspectives on palaeolithic art. Repositório Comum http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/38285 (2021).

Bouzouggar, A. et al. 82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behaviour. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9964–9969 (2007).

d’Errico, F., Henshilwood, C., Vanhaeren, M. & Van Niekerk, K. Nassarius kraussianus shell beads from Blombos Cave: evidence for symbolic behaviour in the Middle Stone Age. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 3–24 (2005).

Grün, R. et al. U-series and ESR analyses of bones and teeth relating to the human burials from Skhul. J. Hum. Evol. 49, 316–334 (2005).

Miller, J. M. & Wang, Y. V. Ostrich eggshell beads reveal 50,000-year-old social network in Africa. Nature 601, 234–239 (2022).

Iliopoulos, A. Early body ornamentation as ego-culture: tracing the co-evolution of aesthetic ideals and cultural identity. Semiotica 2020, 187–233 (2020).

Janowski, M. in Beads and Bead Makers: Gender, Material Culture and Meaning (eds Sciama, L. D. & Eicher, J. B.) 213–246 (Berg Publishers, 1998).

Weiner, A. B. The Trobrianders of Papua New Guinea (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1988).

Cangelosi, A. Evolution of communication and language using signals, symbols, and words. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 5, 93–101 (2001).

Kuhn, L. S. & Stiner, M. C. Paleolithic ornaments: implications for cognition, demography and identity. Diogenes 214, 40–48 (2007).

Newell, R. R., Kielman, D., Constandse-Westermann, T. S., van der Sanden, W. A. B. & van Gijn, A. An Inquiry into the Ethnic Resolution of Mesolithic Regional Groups. The Study of Their Decorative Ornaments in Time and Space (Brill, 1990).

Hamilton, M. J., Milne, B. T., Walker, R. S., Burger, O. & Brown, J. H. The complex structure of hunter–gatherer social networks. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 2195–2203 (2007).

d’Errico, F. & Vanhaeren, M. in Upper Palaeolithic Mortuary Practices: Reflection of Ethnic Affiliation, Social Complexity, and Cultural Turnover (eds Renfrew, C. et al.) 45–62 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Jordan, P. & Shennan, S. Cultural transmission, language, and basketry traditions amongst the California Indians. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 22, 42–74 (2003).

Kovacevic, M., Shennan, S., Vanhaeren, M., d’Errico, F. & Thomas, M. G. in Learning Strategies and Cultural Evolution During the Palaeolithic (eds Mesoudi, A. & Aoki, K.) 103–120 (Springer, 2015).

Lycett, S. J. Confirmation of the role of geographic isolation by distance in among-tribe variations in beadwork designs and manufacture on the High Plains. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 2837–2847 (2019).

Shennan, S. Genes, Memes, and Human History: Darwinian Archaeology and Cultural Evolution (Thames & Hudson, 2002).

Shennan, S. J., Crema, E. R. & Kerig, T. Isolation-by-distance, homophily, and ‘core’ vs. ‘package’ cultural evolution models in Neolithic Europe. Evol. Hum. Behav. 36, 103–109 (2015).

Hardy, O. J. & Vekemans, X. Isolation by distance in a continuous population: reconciliation between spatial autocorrelation analysis and population genetics models. Heredity 83, 145–154 (1999).

Wright, S. Isolation by distance. Genetics 28, 114–138 (1943).

Kozłowski, J. The origin of the Gravettian. Quat. Int. 359, 3–18 (2015).

Taller, A. & Conard, N. J. Were the Technological Innovations of the Gravettian Triggered by Climatic Change? Insights from the Lithic Assemblages from Hohle Fels, SW Germany. PaleoAnthropology 2022, 82–108 (2022).

Wilczyński, J. et al. New radiocarbon dates for the late Gravettian in eastern Central Europe. Radiocarbon 62, 243–259 (2020).

Broglio, A. & Dalmeri, G. Pitture Paleolitiche Nelle Prealpi Venete: Grotta di Fumane e Riparo Dalmeri Vol. 9 (Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, 2005).

de Sonneville-Bordes, D. L’évolution du Paléolithique supérieur en Europe occidentale et sa signification. Bull. Soc. Préhist. Française 63, 3–34 (1966).

Hahn, J. Aurignacien, das ältere Jungpaläolithikum in Mittel-und Osteuropa Vol. 9 (Böhlau, 1977).

Teyssandier, N. L’émergence du Paléolithique supérieur en Europe: mutations culturelles et rythmes d’évolution. PALEO https://doi.org/10.4000/paleo.702 (2007).

Zilhão, J. & d’Errico, F. The Chronology of the Aurignacian and of the Transitional Technocomplexes. Dating, Stratigraphies, Cultural Implications (Instituto Português de Arqueologia, 2003).

Calvo, A. & Arrizabalaga, A. Piecing together a new mosaic: Gravettian lithic resources and economic territories in the Western Pyrenees. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 282 (2020).

Conard, N. J. & Moreau, L. Current research on the Gravettian of the Swabian Jura. Mitt. Ges. Urgesch. 13, 29–57 (2004).

Marreiros, J. & Bicho, N. Lithic technology variability and human ecodynamics during the Early Gravettian of Southern Iberian Peninsula. Quat. Int. 318, 90–101 (2013).

Moreau, L. Geißenklösterle. The Swabian Gravettian in its European context: Geißenklösterle. Das schwäbische Gravettien im europäischen Kontext. Quartär 57, 79–93 (2010).

Polanská, M., Hromadová, B. & Sázelová, S. The Upper and Final Gravettian in Western Slovakia and Moravia. Different approaches, new questions. Quat. Int. 581–582, 205–224 (2021).

Vignoles, A. et al. Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32–28 ky cal. BP) in France. Quat. Sci. Rev. 253, 106766 (2021).

Delporte, H. L’image de la femme dans l’art préhistorique. Rev. Archeol. Centre France 18, 183–184 (1979).

Tripp, A. in Cultural Phylogenetics: Concepts and Applications in Archaeology (ed. Mendoza Straffon, L.) 179–202 (Springer, 2016).

Zilhão, J. & Trinkaus, E. (eds) Portrait of the Artist as a Child. The Gravettian Human Skeleton from the Abrigo Do Lagar Velho and Its Archaeological Context (Min. da Cultura, 2002).

Klaric, L., Guillermin, P. & Aubry, T. Des armatures variées et des modes de production variable. Réflexions à partir de quelques exemples issus du Gravettien d’Europe occidentale (France, Portugal, Allemagne). Gall. Prehist. 51, 113–154 (2009).

Laville, H. & Rigaud, J.-P. The Perigordian V industries in Périgord: typological variations, stratigraphy and relative chronology. World Archaeol. 4, 330–338 (1973).

Rigaud, J.-P., Dibble, H. & Monte-White, A. in Upper Pleistocene Prehistory of Western Eurasia (eds Dibble, H. L. & Monte-White, A.) 387–396 (Univ. Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1988).

Hoffecker, J. F. The Eastern Gravettian ‘Kostenki culture’ as an Arctic adaptation. Anthropol. Pap. Univ. Alsk. 2, 115–136 (2002).

Johnson, R. J., Lanaspa, M. A. & Fox, J. W. Upper Paleolithic figurines showing women with obesity may represent survival symbols of climatic change. Obesity 29, 11–15 (2021).

Weber, G. W. et al. The microstructure and the origin of the Venus from Willendorf. Sci. Rep. 12, 2926 (2022).

Bradtmöller, M., Marreiros, J., Pereira, T. & Bicho, N. Lithic technological adaptation within the Gravettian of the Iberian Atlantic region: results from two case studies. Quat. Int. 406, 3–24 (2016).

Kozłowski, J. K. in The Lithic Raw Material Sources and the Interregional Human Contacts in the Northern Carpathian Regions (ed. Mester, Z.) 63–85 (Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, Institute of Archaeological Sciences of the Eotvos Lorand University Budapest, 2013).

d’Errico, F. et al. Zhoukoudian Upper Cave personal ornaments and ochre: rediscovery and reevaluation. J. Hum. Evol. 161, 103088 (2021).

Kassam, A. Traditional ornament: some general observations. Kenya Past Present https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA02578301_68 (1988).

Fernández, E. A. La explotación de los moluscos marinos en la Cornisa Cantábrica durante el Gravetiense: primeros datos de los niveles E y F de La Garma A (Omoño, Cantabria). Zephyrvs https://revistas.usal.es/uno/index.php/0514-7336/article/view/5567 (2007).

d’Errico, F. & Rigaud, S. Crache perforée dans le Gravettien du sire (Mirefleurs, Puy-de-Dôme). PALEO https://doi.org/10.4000/paleo.2172 (2011).

d’Errico, F. & Vanhaeren, M. in Death Shall Have No Dominion: The Archaeology of Mortality and Immortality, a Worldwide Perspective (eds Renfrew, C. et al.) 35–48 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Taborin, Y. in Hunters of the Golden Age. The Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Eurasia 30,000–20,000 BP (eds Roebroeks, W. et al.) 135–142 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

Lisá, L. et al. The role of abiotic factors in ecological strategies of Gravettian hunter–gatherers within Moravia, Czech Republic. Quat. Int. 294, 71–81 (2013).

Wilczyński, J. et al. Population mobility and lithic tool diversity in the Late Gravettian – the case study of Lubná VI (Bohemian Massif). Quat. Int. 587, 103–126 (2021).

Chapais, B. in Mind the Gap (eds Kappeler, P. & Silk, J.) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02725-3_2 19-51 (Springer, 2010).

Walker, R. S., Hill, K. R., Flinn, M. V. & Ellsworth, R. M. Evolutionary history of hunter–gatherer marriage practices. PLoS ONE 6, e19066 (2011).

Beresford-Jones, D. et al. Rapid climate change in the Upper Palaeolithic: the record of charcoal conifer rings from the Gravettian site of Dolní Vĕstonice, Czech Republic. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 1948–1964 (2011).

Haws, J. et al. Human adaptive responses to climate and environmental change during the Gravettian of Lapa do Picareiro (Portugal). Quat. Int. 587–588, 4–18 (2020).

Maier, A. Population and settlement dynamics from the Gravettian to the Magdalenian. Mitt. Ges. Urgesch. 26, 83–101 (2017).

Bradley, R. The destruction of wealth in later prehistory. Man 17, 108–122 (1982).

Testart, A. Des Dons et des Dieux. Anthropologie Religieuse et Sociologie Comparative (ERRANCE1, 2006).

Riel-Salvatore, J. & Gravel-Miguel, C. in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial (eds Stutz, L. N. & Tarlow, S.) Ch. 17 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Oliva, M. Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Moravia Vol. 11 (Moravian Museum, 2005).

Kacki, S. et al. Complex mortuary dynamics in the Upper Paleolithic of the decorated Grotte de Cussac, France. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 14851–14856 (2020).

Duarte, C. et al. The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7604–7609 (1999).

Einwögerer, T. et al. Upper Palaeolithic infant burials. Nature 444, 285 (2006).

Sinitsyn, A. A. Earliest Upper Palaeolithic layers at Kostenki 14 (Markina gora): preliminary results of the 1998–2001 excavations. BAR Int. Ser. 1240, 181–190 (2004).

Wilczyński, J. et al. A mid Upper Palaeolithic child burial from Borsuka Cave (southern Poland). Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 26, 151–162 (2016).

Abramovitch, H. Death, anthropology of. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.12052-5 (2015).

Formicola, V., Pontrandolfi, A. & Svoboda, J. The Upper Paleolithic triple burial of Dolní Věstonice: pathology and funerary behavior. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 115, 372–379 (2001).

Grosman, L., Munro, N. D. & Belfer-Cohen, A. A 12,000-year-old Shaman burial from the southern Levant (Israel). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17665–17669 (2008).

Kaufman, S. R. & Morgan, L. M. The anthropology of the beginnings and ends of life. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 34, 317–341 (2005).

Petru, S. Identity and fear–burials in the Upper Palaeolithic. Doc. Praehist. 45, 6–13 (2018).

Formicola, V. & Buzhilova, A. P. Double child burial from Sunghir (Russia): pathology and inferences for Upper Paleolithic funerary practices. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 124, 189–198 (2004).

Trinkaus, E. & Buzhilova, A. P. Diversity and differential disposal of the dead at Sunghir. Antiquity 92, 7–21 (2018).

Bicho et al. Early Upper Paleolithic colonization across Europe: time and mode of the Gravettian diffusion. PLoS ONE 12, e0178506 (2017).

Bocquet-Appel, J.-P., Demars, P.-Y., Noiret, L. & Dobrowsky, D. Estimates of Upper Palaeolithic meta-population size in Europe from archaeological data. J. Archaeol. Sci. 32, 1656–1668 (2005).

Housley, R. A., Gamble, C. S., Street, M. & Pettitt, P. Radiocarbon evidence for the Lateglacial human recolonisation of northern Europe. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 63, 25–54 (1997).

Ramsey, C. B. Radiocarbon calibration and analysis of stratigraphy: the OxCal program. Radiocarbon 37, 425–430 (1995).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Dubin, L. S. The History of Beads: From 30,000 B.C. to the Present (Thames and Hudson, 1987).

Erikson, J. M. The Universal Bead (W.W. Norton, 1969).

Taborin, Y. La parure en coquillage au Palaéolithique. Gall. Prehist. https://www.persee.fr/doc/galip_0072-0100_1993_sup_29_1 (1993).

Whallon, R. & Brown, J. Essays on Archaeological Typology (Center for American Archaeology Press, 1982).

Adams, W. Y. & Adams, E. W. Archaeological Typology and Practical Reality: A Dialectical Approach to Artefact Classification and Sorting (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991).

Whittaker, J. C., Caulkins, D. & Kamp, K. A. Evaluating consistency in typology and classification. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 5, 129–164 (1998).

Lartet, E. & Christy, H. Cavernes du Périgord: Objets Gravés et Sculptés des Temps Pré-historiques dans L’europe Occidentale (Revue Archéologique, 1864).

Riviere, É. Note sur l’homme fossile des cavernes de Baoussé-Roussé (Italie), dites grottes de Menton. Bull. Mem. Soc. Anthropol. Paris 7, 584–589 (1872).

d’Errico, F. & Villa, P. Holes and grooves: the contribution of microscopy and taphonomy to the problem of art origins. J. Hum. Evol. 33, 1–31 (1997).

Liiv, I. Seriation and matrix reordering methods: an historical overview. Stat. Anal. Data Min. 3, 70–91 (2010).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electronica 4, 4 (2001).

Newman, M. E. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8577–8582 (2006).

Anderson, M. J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (Department of Statistics, Univ. Auckland, 2005).

McArdle, B. H. & Anderson, M. J. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82, 290–297 (2001).

Jaccard, P. Étude comparative de la distribution florale dans une portion des Alpes et des Jura. Bull. Soc. Vaud. Sci. Nat. 37, 547–579 (1901).

Rogers, D. S. & Ehrlich, P. R. Natural selection and cultural rates of change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3416–3420 (2008).

Shennan, S. J. & Bentley, R. A. in Cultural Transmission and Archaeology: Issues and Case Studies (ed. O'Brien, M. J.) 164–177 (Society for American Archaeology, 2008).

Ricotta, C., Podani, J. & Pavoine, S. A family of functional dissimilarity measures for presence and absence data. Ecol. Evol. 6, 5383–5389 (2016).

Bathke, A. C. et al. Testing mean differences among groups: multivariate and repeated measures analysis with minimal assumptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 348–359 (2018).

Gower, J. C. Some distance properties of latent root and vector methods used in multivariate analysis. Biometrika 53, 325–338 (1966).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Evans, J. D., Cann, J. R., Renfrew, A. C., Cornwall, I. W. & Western, A. C. Excavations in the Neolithic settlement of Knossos, 1957-60. Part I. Annu. Br. Sch. Athens 59, 132–240 (1964).

Collard, M., Shennan, S. J., Buchanan, B. & Bentley, R. A. in Handbook of Archaeological Theories (eds Bentley, R. A. et al.) 203–223 (Altamira Press, 2008).

Gray, R. D., Greenhill, S. J. & Ross, R. M. The pleasures and perils of Darwinizing culture (with phylogenies). Biol. Theory 2, 360–375 (2007).

Steele, J., Jordan, P. & Cochrane, E. Evolutionary approaches to cultural and linguistic diversity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 3781–3785 (2010).

Gray, R. D., Bryant, D. & Greenhill, S. J. On the shape and fabric of human history. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 3923–3933 (2010).

Greenhill, S. J., Currie, T. E. & Gray, R. D. Does horizontal transmission invalidate cultural phylogenies? Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 2299–2306 (2009).

Bryant, D. & Moulton, V. Neighbor-net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 255–265 (2004).

Bryant, D., Filimon, F. & Gray, R. D. in The Evolution of Cultural Diversity (eds Mace, R. et al.) 77–93 (Routledge, 2016).

Huson, D. H. & Bryant, D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 254–267 (2006).

Holland, B. R., Huber, K. T., Dress, A. & Moulton, V. δ plots: a tool for analyzing phylogenetic distance data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 2051–2059 (2002).

Meirmans, P. G. The trouble with isolation by distance. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2839–2846 (2012).

Mantel, N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 27, 209–220 (1967).

Borcard, D. & Legendre, P. Is the Mantel correlogram powerful enough to be useful in ecological analysis? A simulation study. Ecology 93, 1473–1481 (2012).

Hammer, Ø. Spectral analysis of a Plio-Pleistocene multispecies time series using the Mantel periodogram. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 243, 373–377 (2007).

Legendre, P. & Fortin, M. J. Spatial pattern and ecological analysis. Vegetatio 80, 107–138 (1989).

Gallardo-Cruz, J. A., Meave, J. A., Pérez-García, E. A. & Hernández-Stefanoni, J. L. Spatial structure of plant communities in a complex tropical landscape: implications for β-diversity. Community Ecol. 11, 202–210 (2010).

Baddeley, A., Rubak, E. & Turner, R. Spatial Point Patterns: Methodology and Applications with R (CRC Press, 2015).

Legendre, P. Comparison of permutation methods for the partial correlation and partial Mantel tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 67, 37–73 (2000).

Smouse, P., Long, J. & Sokal, R. Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the Mantel test of matrix correspondence. Syst. Zool. 35, 627–632 (1986).

Baker, J., Rigaud, S., Vanhaeren, M. & d’Errico, F. Cro-Magnon personal ornaments revisited. PALEO 32, 40–73 (2022).

Zilhão, J. et al. Revisiting the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic archaeology of Gruta do Caldeirão (Tomar, Portugal). PLoS ONE 16, e0259089 (2021).

QGIS Geographic Information System (QGIS.org., 2020).

ETOPO 2022 15 Arc-Second Global Relief Model (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, accessed 25 August 2023); https://doi.org/10.25921/fd45-gt74

Lambeck, K. & Chappell, J. Sea level change through the last glacial cycle. Science 292, 679–686 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Barraquand and F. Santos for useful advice regarding the statistical analyses. This work was supported by the French National Research Agency under the IDEX Bordeaux NETAWA Emergence project No. ANR-10-IDEX-03-02 ‘Out of the Core: Exploring social NETworks at the dawn of Agriculture in Western Asia 10,000 years ago’ (S.R., D.P.), the CNRS Momentum Project (S.R., D.P.), the ERC Synergy QUANTA (Grant No. 951388) (F.d’E., L.A.C.), the University of Bordeaux ‘Grand Programme de Recherche’ ‘Human Past’ (F.d’E., S.R., D.P.), the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, SFF Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour (SapienCE), project number 262618 (F.d’E.), the Talents Programme (Grant No. 191022_001) (F.d’E.) and the ‘Projet Collectif de Recherche’ ‘Gravettien’ (J.B., S.R., F.d’E.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B., S.R. and F.d’E. wrote the paper. J.B., S.R., D.P., L.A.C. and F.d’E. conceived and designed the experiments. J.B., D.P. and L.A.C. performed the experiments. J.B., S.R., D.P., L.A.C. and F.d’E. analysed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

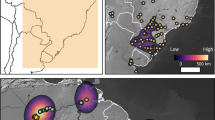

Extended Data Fig. 1 Map showing the locations of Gravettian occupation and burial sites containing personal ornaments.

a) Geographical distribution of the Gravettian burials yielding personal ornaments. BS1, Krems-Wachtberg; BS2, Lagar Velho; BS3, Paviland; BS4, Arene Candide; BS5, Kostenki 14; BS6, Ostuni; BS7, Fanciulli; BS8, Paglicci; BS9, Dolni Vestonice; BS10, Brno; BS11, Cro-Magnon; BS12, Baousso da Torre; BS13, Barma Grande; BS14, Grotta del Caviglione; BS15, Veneri Parabita; BS16, Predmosti; BS17, Borsuka Cave. b) Geographical distribution of the Gravettian occupation sites yielding personal ornaments in Europe with the Dordogne region enlarged at the bottom right (c). S1, Poiana Ciresului-Piatra Neamt; S2, Kostenki 17; S3, Foradada Cave; S4, Riparo Mochi; S5, Franchthi Cave; S6, Mitoc-Malu Galben; S7, Brinzeni Cave; S8, Duruitoarea Veche Cave; S9, Cosauti; S10, Climauti; S11, Molodova V; S12, Gargas Cave; S13, Brillenhohle; S14, Geisenklosterle; S15, Hohle Fels; S16, Ollersdorf/Heidenberg; S17, Mainz-Linsenberg; S18, Nerja Cave; S31, Isturitz Cave; S32, Abri des Pecheurs; S33, Baume Perigaud; S34, Pushkari; S35, Grotta della Serratura; S36, Vale Boi; S37, El Cuco; S38, Sire; S39, Tibrinu; S40, Gura Cheii-Rasnov Cave; S41, Garma A; S42, Cova Gran de Santa Linya; S43, La Grotte du Figuier; S44, Cova de les Cendres; S45, Cova del Comte; S47, Grub-Kranawetberg; S48, Grotte du Renne; S49, Krakow Spadzista; S50, Grotte du Pape; S52, Kostenki 21; S53, Kostenki 8; S54, Kostenki 4; S55, Aitzbitarte; S56, Amiens-Renancourt; S57, Mollet; S58, Arbreda Cave; S59, Jaksice; S60, Les Bossats; S61, La Bergerie; S62, Lapa do Picareiro; S63, La Fuente del Salin; S66, Krems-Wachtberg; S67, Willendorf; S70, Buran-Kaya; S71, Weinberghohlen; S72, Krems-Hundsteig; S73, Obere Klause; S74, Betche-aux-Rotches de Spy; S75, Goyet; S77, Dolni Vestonice 1; S80, Le Blot; S81, Pavlov; S82, Oblazowa Cave; S83, Ciaoarei Cave; S84, Reclau Viver Cave; S85, Paviland; S86, La Vina; S87, Cueto de la Mina; S88, Cueva Morin; S89; Bolinkoba; S90, Amalda; S91, Alkerdi; S92, Antolinako Koba; S93, Abric Romani; S94, Cueva de Ardales; S95, Gruta do Caldeirao; S96, Cova Beneito; S97, Zajara; S98, Los Morceguillos. c) Geographical distribution of the Gravettian occupation sites yielding personal ornaments from the Dordogne region. S19, Le Facteur; S21, Labattut; S20, Le Flageolet; S22, Laussel; S23, Le Poisson; S24, Les Rochers de l’Acier; S25, Le Roque-Saint-Christophe; S26, Le Ruth-Pages; S27, Grotte de Tourtoirac; S28, Abri Laraux; S29, Grotte de Pair-non-Pair; S30, Le Roc de Gavaudun; S46, Le Fourneau du Diable; S51, La Gravette; S64, Les Vachons; S65, La Ferrassie; S68, Le Petit-Puyrousseau; S69, Abri Pataud; S78, Laugerie-Haute; S79, Masnaigre. Maps created on QGIS using ETOPO1 Global Relief Model data with a modern and Gravettian coastline at −100 m142.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Two-tailed Mantel correlogram established for the bead-type associations recorded at Gravettian occupation sites.

(a), and burial sites (b). Unit of geographic distance for a1 and b1: 500 km, a2 and b2: 250 km, a3 and b3: 100 km. Black squares indicate significant P-values, white squares non-significant P-values.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Boxplot of radiocarbon ages associated with Gravettian occupation and burial sites yielding personal ornaments in different regions of Europe.

Maximum value = 36,280.5 years, Minimum = 23,525 years. Dark grey = occupation sets, light grey = burial sets. The box extends from the lower to upper quartile, with the whisker variability indicating outside the upper and lower quartiles. ‘eastern Europe’ = N = 8, ‘south Iberia’ = N = 8, ‘northwestern Europe’ = N = 4, ‘north Iberia’ = N = 8, ‘Central Europe’ = N = 9, ‘eastern (Burials)’ = N = 9, ‘north Italy (Burials)’ = N = 11, ‘south Italy (Burials)’ = N = 6. Total = N = 63.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Results 1 and 2, Figs. 1–5 and Tables 1–6.

Supplementary Table 1

Bead coding. An excel spreadsheet containing each of the discrete bead types and the code used for each.

Supplementary Table 2

All datasets. An excel spreadsheet containing 7 separate worksheets.

Supplementary Table 3

Occupation Table. An excel spreadsheet containing the attributes and personal ornaments of the occupation sites.

Supplementary Table 4

Burial Table. An excel spreadsheet containing the attributes and personal ornaments of the buried individuals.

Supplementary Table 5

All distance matrices. An excel spreadsheet containing 14 separate worksheets.

Supplementary Table 6

All datasets used for the Mantel test modelling. An excel spreadsheet containing 5 separate worksheets.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, J., Rigaud, S., Pereira, D. et al. Evidence from personal ornaments suggest nine distinct cultural groups between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago in Europe. Nat Hum Behav 8, 431–444 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01803-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01803-6

This article is cited by

-

Signalling Palaeolithic identity

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)