Abstract

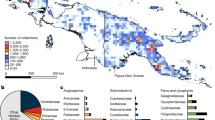

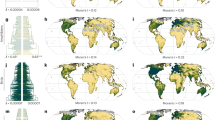

Herbarium collections shape our understanding of Earth’s flora and are crucial for addressing global change issues. Their formation, however, is not free from sociopolitical issues of immediate relevance. Despite increasing efforts addressing issues of representation and colonialism in natural history collections, herbaria have received comparatively less attention. While it has been noted that the majority of plant specimens are housed in the Global North, the extent and magnitude of this disparity have not been quantified. Here we examine the colonial legacy of botanical collections, analysing 85,621,930 specimen records and assessing survey responses from 92 herbarium collections across 39 countries. We find an inverse relationship between where plant diversity exists in nature and where it is housed in herbaria. Such disparities persist across physical and digital realms despite overt colonialism ending over half a century ago. We emphasize the need for acknowledging the colonial history of herbarium collections and implementing a more equitable global paradigm for their collection, curation and use.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data discussed in the paper are either publicly available through GBIF (https://www.gbif.org/; https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.nt5wkx) or Index Herbariorum (https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The_World_Herbaria_2020_7_Jan_2021.pdf) or are in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis is available at https://github.com/shandongfx/paper_specimen_2023.

References

Thiers, B. M. The World’s Herbaria 2020: A Summary Report Based on Data from Index Herbariorum Issue 5.0 (NYBG Steere Herbarium, 2021).

Willis, C. G. et al. Old plants, new tricks: phenological research using herbarium specimens. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32, 531–546 (2017).

Heberling, J. M., Miller, J. T., Noesgaard, D., Weingart, S. B. & Schigel, D. Data integration enables global biodiversity synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018093118 (2021).

Hedrick, B. et al. Digitization and the future of natural history collections. Bioscience 70, 243–251 (2020).

Funk, V. A. 100 uses for an herbarium: well at least 72. Am. Soc. Plant Taxon. Newsl. 7, 17–19 (2003).

Carine, M. A. et al. Examining the spectra of herbarium uses and users. Bot. Lett. 165, 328–336 (2018).

Meineke, E. K., Classen, A. T., Sanders, N. J. & Davies, T. J. Herbarium specimens reveal increasing herbivory over the past century. J. Ecol. 107, 105–117 (2019).

Lang, P. L. M., Willems, F. M., Scheepens, J. F., Burbano, H. A. & Bossdorf, O. Using herbaria to study global environmental change. N. Phytol. 221, 110–122 (2019).

Lavoie, C. Biological collections in an ever changing world: herbaria as tools for biogeographical and environmental studies. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 15, 68–76 (2013).

Davis, C. C., Willis, C. G., Connolly, B., Kelly, C. & Ellison, A. M. Herbarium records are reliable sources of phenological change driven by climate and provide novel insights into species’ phenological cueing mechanisms. Am. J. Bot. 102, 1599–1609 (2015).

Bonal, D. et al. Leaf functional response to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last century in two northern Amazonian tree species: a historical δ13C and δ18O approach using herbarium samples. Plant. Cell Environ. 34, 1332–1344 (2011).

Rudin, S. M., Murray, D. W. & Whitfeld, T. J. S. Retrospective analysis of heavy metal contamination in Rhode Island based on old and new herbarium specimens. Appl. Plant Sci. 5, 1600108 (2017).

Peñuelas, J. & Filella, I. Herbaria century record of increasing eutrophication in Spanish terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 7, 427–433 (2001).

Lees, D. C. et al. Tracking origins of invasive herbivores through herbaria and archival DNA: the case of the horse-chestnut leaf miner. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 322–328 (2011).

Delisle, F., Lavoie, C., Jean, M. & Lachance, D. Reconstructing the spread of invasive plants: taking into account biases associated with herbarium specimens. J. Biogeogr. 30, 1033–1042 (2003).

Vogel, G. Natural history museums face their own past. Science 363, 1371–1372 (2019).

Wintle, C. Decolonizing the Smithsonian: museums as microcosms of political encounter. Am. Hist. Rev. 121, 1492–1520 (2016).

Wandersee, J. H. & Schussler, E. E. Preventing plant blindness. Am. Biol. Teach. 61, 82–86 (1999).

Brockway, L. H. Science and colonial expansion: the role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens. Am. Ethnol. 6, 449–465 (1979).

Shellam, T., Nugent, M., Konishi, S. & Cadzow, A. Brokers and Boundaries: Colonial Exploration in Indigenous Territory (ANU Press, 2016).

Kennedy, D. The Last Blank Spaces (Harvard Univ. Press, 2013).

Reynolds, H. With the White People (Penguin, 1990).

Peterson, A. T., Soberón, J. & Krishtalka, L. A global perspective on decadal challenges and priorities in biodiversity informatics. BMC Ecol. 15, 15 (2015).

Bakker, F. T. et al. The Global Museum: natural history collections and the future of evolutionary science and public education. PeerJ 8, e8225 (2020).

Davis, C. C. The herbarium of the future. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 412–423 (2022).

Voeks, R. A. The Ethnobotany of Eden: Rethinking the Jungle Medicine Narrative (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018).

Webb, C. O., Slik, J. W. F. & Triono, T. Biodiversity inventory and informatics in Southeast Asia. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 955–972 (2010).

Hughes, A. C. et al. Sampling biases shape our view of the natural world. Ecography 44, 1259–1269 (2021).

Brown, J. H. Why are there so many species in the tropics? J. Biogeogr. 41, 8–22 (2014).

Paton, A. et al. Plant and fungal collections: current status, future perspectives. Plants People Planet 2, 499–514 (2020).

Daru, B. H. et al. Widespread sampling biases in herbaria revealed from large-scale digitization. N. Phytol. 217, 939–955 (2018).

Drew, J. A., Moreau, C. S. & Stiassny, M. L. J. Digitization of museum collections holds the potential to enhance researcher diversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1789–1790 (2017).

Breckenridge, K. The politics of the parallel archive: digital imperialism and the future of record-keeping in the age of digital reproduction. J. South. Afr. Stud. 40, 499–519 (2014).

Feng, X. et al. A review of the heterogeneous landscape of biodiversity databases: opportunities and challenges for a synthesized biodiversity knowledge base. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 1242–1260 (2022).

Das, S. & Lowe, M. Nature read in black and white: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections. J. Nat. Sci. Collect. 6, 4–14 (2018).

Eichhorn, M. P., Baker, K. & Griffiths, M. Steps towards decolonising biogeography. Front. Biogeogr. 12, e44795 (2019).

Smith, G. F. The African Plants Initiative: a big step for continental taxonomy. Taxon 53, 1023–1025 (2004).

Rabeler, R. K. et al. Herbarium practices and ethics, III. Syst. Bot. 44, 7–13 (2019).

Tydecks, L., Jeschke, J. M., Wolf, M., Singer, G. & Tockner, K. Spatial and topical imbalances in biodiversity research. PLoS ONE 13, e0199327 (2018).

Asase, A., Mzumara‐Gawa, T. I., Owino, J. O., Peterson, A. T. & Saupe, E. Replacing ‘parachute science’ with ‘global science’ in ecology and conservation biology. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 4, e517 (2021).

Gemmell, N. J. et al. The tuatara genome reveals ancient features of amniote evolution. Nature 584, 403–409 (2020).

Roque, R. & Wagner, K. A. in Cambridge Imperial and Post-colonial Studies Series: Engaging Colonial Knowledge (eds Roque, R. & Wagner, K. A.) 1–32 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Mayer, T. & Zignago, S. Notes on CEPII’s Distances Measures: The GeoDist Database (SSRN, 2011); https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1994531

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the past and continuing contributions of colonized peoples to botanical science and knowledge. This work was largely conducted in institutions on the traditional territory of the Wampanoag, Massachusetts, Miami and Apalachee peoples. We thank the herbaria that contributed data to this work: AAU, AD, ASSAM, ASU, B, BISH, BM, BO, BP, BR, BRI, BRNU, BSA, BSHC, BSID, C, CANB, CAS, CHR, CL, CM, COL, CORD, DAO, DUKE, EA, F, FI, FLAS, FR, G, GB, GH, A, ECON, AMES, FH, NEBC, GJO, GOET, GZU, H, HAL, HIRO, IBSC, SI, K, KH, KW, L, LBL, LE, LIL, LY, M, MA, MEL, MEXU, MICH, MIN, MO, MT, MW, NCU, KB/NIBR, NICH, NSW, NY, O, OULU, P/PC, PAD, PE, PERTH, PRC, PRE/NBG/NH, QFA, RM/USFS, RO, S, SI, SING, SP, STR, TAIF, TASH, TENN, TEX/LL, TNS, TUR, UC, JEPS, UPS, US, USM, VEN, W, WTU and ZT. This work was supported by the Czech Academy of Sciences (grant no. RVO 67985939 to J.D.) and the Komarov Botanical Institute, RAS (grant no. AAAA-A19-119031290052-1 to D. Melnikov). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S.P. and C.C.D. conceived the initial idea, which was refined through discussions with X.F. D.S.P and X.F. analysed the specimen data and designed the questionnaire with C.C.D. D.S.P. supervised the study and wrote the original draft with input from X.F. All other authors provided data from their respective institutions. All authors contributed to further revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Data 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, D.S., Feng, X., Akiyama, S. et al. The colonial legacy of herbaria. Nat Hum Behav 7, 1059–1068 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01616-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01616-7

This article is cited by

-

Urban inequalities

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

Online herbaria databases allow testing the minimum residence time among invasive and non-invasive alien species

Plant Ecology (2024)

-

The past is a foreign country

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)

-

Pressed for space

Nature Plants (2023)

-

The road to herbaria: Teaching and learning about biology, aesthetics, and the history of botany

Journal of Biosciences (2023)