Abstract

The geographic expansion of Homo sapiens populations into southeastern Europe occurred by ∼47,000 years ago (∼47 ka), marked by Initial Upper Palaeolithic (IUP) technology. H. sapiens was present in western Siberia by ∼45 ka, and IUP industries indicate early entries by ∼50 ka in the Russian Altai and 46–45 ka in northern Mongolia. H. sapiens was in northeastern Asia by ∼40 ka, with a single IUP site in China dating to 43–41 ka. Here we describe an IUP assemblage from Shiyu in northern China, dating to ∼45 ka. Shiyu contains a stone tool assemblage produced by Levallois and Volumetric Blade Reduction methods, the long-distance transfer of obsidian from sources in China and the Russian Far East (800–1,000 km away), increased hunting skills denoted by the selective culling of adult equids and the recovery of tanged and hafted projectile points with evidence of impact fractures, and the presence of a worked bone tool and a shaped graphite disc. Shiyu exhibits a set of advanced cultural behaviours, and together with the recovery of a now-lost human cranial bone, the record supports an expansion of H. sapiens into eastern Asia by about 45 ka.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the artefacts referred to in this study are curated in the IVPP, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. The basic measurement data of the lithic artefacts can be found in Supplementary Table 1, and the micro-CT reconstruction of the shaped bone tool is in Supplementary Video 1. All other relevant data are available in the main text or the accompanying supplementary materials. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The CQL code for the Bayesian age model is provided in Supplementary Table 9.

References

Fewlass, H. et al. A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 794–801 (2020).

Fu, Q. et al. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449 (2014).

Rybin, E. & Khatsenovich, A. Middle and Upper Paleolithic Levallois technology in eastern Central Asia. Quat. Int. 535, 117–138 (2020).

Zwyns, N. et al. The northern route for human dispersal in central and northeast Asia: new evidence from the site of Tolbor-16, Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 9, 11759 (2019).

Fu, Q. et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2223–2227 (2013).

Li, F., Petraglia, M., Roberts, P. & Gao, X. The northern dispersal of early modern humans in eastern Eurasia. Sci. Bull. 65, 1699–1701 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Chronology and techno-typology of the Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Shuidonggou area, northern China. J. World Prehist. 32, 111–141 (2019).

Bae, C. J., Douka, K. & Petraglia, M. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives. Science 358, eaai9067 (2017).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. Rethinking the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Evol. Anthropol. 24, 149–164 (2015).

Harvati, K. et al. Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia. Nature 571, 500–504 (2019).

Kuhn, S. L. Initial Upper Paleolithic: a (near) global problem and a global opportunity. Archaeol. Res. Asia 17, 2–8 (2019).

Zwyns, N. The Initial Upper Paleolithic in central and East Asia: blade technology, cultural transmission, and implications for human dispersals. J. Paleolit. Archaeol. 4, 19 (2021).

Hajdinjak, M. et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic humans in Europe had recent Neanderthal ancestry. Nature 592, 253–257 (2021).

Sikora, M. et al. The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene. Nature 570, 182–188 (2019).

Dennell, R., Martinón-Torres, M. A., de Castro, J. B. & Gao, X. Demographic history of Late Pleistocene China. Quat. Int. 559, 4–13 (2020).

Wang, F. G. et al. Innovative ochre processing and tool use in China 40,000 years ago. Nature 603, 284–289 (2022).

Li, F., Bae, C. J., Ramsey, B., Chen, F. & Gao, X. Re-dating Zhoukoudian Upper Cave, northern China and its regional significance. J. Hum. Evol. 121, 170–177 (2018).

Devièse, T. et al. Compound-specific radiocarbon dating and mitochondrial DNA analysis of the Pleistocene hominin from Salkhit Mongolia. Nat. Commun. 10, 274 (2019).

Mao, X. W. et al. The deep population history of northern East Asia from the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene. Cell 184, 3256–3266 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Heading north: Late Pleistocene environments and human dispersals in central and eastern Asia. PLoS ONE 14, e0216433 (2019).

Shichi, K. et al. Climate amelioration, abrupt vegetation recovery, and the dispersal of Homo sapiens in Baikal Siberia. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi0189 (2023).

Nian, X., Gao, X. & Zhou, L. Chronological studies of Shuidonggou (SDG) locality 1 and their significance for archaeology. Quat. Int. 347, 5–11 (2014).

Keates, S. G. & Kuzmin, Y. V. Shuidonggou localities 1 and 2 in northern China: archaeology and chronology of the Initial Upper Palaeolithic in north-east Asia. Antiquity 89, 714–720 (2015).

Zhang, J. F. et al. Optically stimulated luminescence dating of cave deposits at the Xiaogushan prehistoric site, northeastern China. J. Hum. Evol. 59, 2453–2465 (2010).

d’Errico, F. et al. Zhoukoudian Upper Cave personal ornaments and ochre: rediscovery and reevaluation. J. Hum. Evol. 161, 103088 (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. After the blades: the late MIS3 flake-based technology at Shuidonggou Locality 2, North China. PLoS ONE 17, e0274777 (2022).

Yu, J. J. et al. The Tongtian Dong Site in Jeminay County, Xinjiang. Archaeology 7, 3–14 (2018).

Li, F. et al. The easternmost Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) from Jinsitai Cave, North China. J. Hum. Evol. 114, 76–84 (2018).

Jia, L. P., Gai, P. & You, Y. Z. The report of excavation at Shiyu site in Shanxi Province. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 1, 39–58 (1972).

You, Y. Z. & Li, Z. W. Discussion on several issues about Shiyu Site. Archaeol. Cult. Relics 5, 44–48 (1982).

Zhang, J. S. Study on the bone fragments from Shiyu. Acta Anthropol. Sin. 3, 333–345 (1991).

Kuzmin, A. Y. Obsidian as a commodity to investigate human migrations in the Upper Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Paleometal of Northeast Asia. Quat. Int. 442, 5–11 (2017).

Yang, S., Deng, C., Zhu, R. & Petraglia, M. The Paleolithic in the Nihewan Basin, China: evolutionary history of an Early to Late Pleistocene record in eastern Asia. Evol. Anthropol. 29, 125–142 (2020).

Beyssac, O., Goffé, B., Chopin, C. & Rouzaud, J. N. Raman spectra of carbonaceous material in metasediments: a new geothermometer. J. Metamorph. Geol. 20, 859–871 (2002).

Gilligan, I. The prehistoric development of clothing: archaeological implications of a thermal model. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 17, 15–80 (2010).

D’Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M. & Queffelec, A. Les galets perforés de Praileaitz I (Deba, Gipuzkoa): la cueva de Praileaitz I (Deba, Gipuzkoa, Euskal Herria). Interv. Arqueol. 2000–2009 1, 453–484 (2017).

Currery, J. D. Bones: Structure and Mechanics (Princeton Univ. Press, 2002).

Kolb, C. et al. Mammalian bone palaeohistology: a survey and new data with emphasis on island forms. PeerJ 3, e1358 (2015).

Bae, C. J. Paleolithic cave home bases, bone tools, and art and symbolism: perspectives from Korea. Hoseo Archaeol. 29, 50–95 (2013).

Norton, C. J. The current state of Korean paleoanthropology. J. Hum. Evol. 38, 803–825 (2000).

Jia, L., Wei, Q. & Li, C. Report on the excavation of Xujiayao Man Site in 1976. Vertebr. Palasiat. 17, 277–293 (1979).

Pei, W. C. On the Upper Cave industry. Palaeontol. Sin. 9, 1–59 (1939).

Sohn, P., Park, Y. & Han, C. Yonggul Cave: palaeontological evidence and cultural behaviour. Bull. Ippa. 10, 92–98 (1991).

Doyon, L., Li, Z., Wang, H., Geis, L. & d’Errico, F. A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. PLoS ONE 16, e0250156 (2021).

Bae, K. Origin and patterns of the Upper Paleolithic industries in the Korean Peninsula and movement of modern humans in East Asia. Quat. Int. 221, 103–112 (2010).

Izuho, M. & Kaifu, Y. in The Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Palaeolithic Asia (eds Kaifu, Y. et al.) 289–313 (Texas A & M Univ. Press, 2015).

Lee, G. K. & Sano, K. Were tanged points mechanically delivered armatures? Functional and morphometric analyses of tanged points from an Upper Paleolithic site at Jingeuneul, Korea. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 2453–2465 (2019).

Bae, C. J. Late Pleistocene human evolution in eastern Asia: behavioral perspectives. Curr. Anthropol. 58, 514–526 (2017).

Massilani, D. et al. Denisovan ancestry and population history of early East Asians. Science 370, 579–583 (2020).

Zhang, D. J. et al. Denisovan DNA in Late Pleistocene sediments from Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau. Science 370, 584–587 (2020).

Jiang, P. A fossil human tooth from Jilin Province. Vertebr. Palasiat. 20, 65–71 (1982).

Xie, J. Y., Zhang, Z. B. & Yang, F. X. The human fossil found in Wushan, Gansu Province. Prehistory 4, 47–51+99 (1987).

Gao, X. & Norton, C. J. Critique of the Chinese ‘Middle Paleolithic’. Antiquity 76, 397–412 (2002).

Brantingham, P. J., Olsen, J. W., Rech, J. A. & Krivoshapkin, A. I. Raw material quality and prepared core technologies in northeast Asia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 27, 255–271 (2000).

Ramsey, B. C., Higham, T. F. G., Bowles, A. & Hedges, R. Improvements to the pre-treatment of bone at Oxford. Radiocarbon 46, 155–163 (2004).

Ramsey, B. C., Higham, T. F. G. & Leach, P. Towards high-precision AMS: progress and limitations. Radiocarbon 46, 17–24 (2004).

Higham, T., Jacobi, R. M. & Bronk Ramsey, C. AMS radiocarbon dating of ancient bone using ultrafiltration. Radiocarbon 48, 179–195 (2006).

Brock, F., Higham, T., Ditchfield, P. & Ramsey, C. B. Current pretreatment methods for AMS radiocarbon dating at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Radiocarbon 52, 103–112 (2010).

Reimer, P. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Ramsey, B. C. OxCal 4.4 Manual, https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/oxcalhelp/hlp_contents.html (2021).

Huntley, D. J., Godfrey-Smith, D. I. & Thewalt, M. L. W. Optical dating of sediments. Nature 313, 105–107 (1985).

Aitken, M. J. An Introduction to Optical Dating: The Dating of Quaternary Sediments by the Use of Photon-Stimulated Luminescence (Oxford Univ. Press,1998).

Roberts, R. G. et al. Optical dating in archaeology: thirty years in retrospect and grand challenges for the future. J. Archaeol. Sci. 56, 41–60 (2015).

Galbraith, R. F., Roberts, R. G., Laslett, G. M., Yoshida, H. & Olley, J. M. Optical dating of single and multiple grains of quartz from Jinmium rock shelter, northern Australia: Part I, Experimental design and statistical models. Archaeometry 41, 339–364 (1999).

Murray, A. S. & Wintle, A. G. The single aliquot regenerative dose protocol: potential for improvements in reliability. Radiat. Meas. 37, 377–381 (2003).

Murray, A. S. & Wintle, A. G. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose procedure. Radiat. Meas. 32, 57–73 (2000).

Li, B. & Li, S. H. Luminescence dating of K-feldspar from sediments: a protocol without anomalous fading correction. Quat. Geochronol. 6, 468–479 (2011).

Zhang, J. F., Zhou, L. P. & Yue, S. Y. Dating fluvial sediments by optically stimulated luminescence: selection of equivalent doses for age calculation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 1123–1129 (2003).

OxCal v.4.1.3 (Univ. Oxford, 2009).

Ramsey, B. C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Jia, W. P. et al. New pieces: the acquisition and distribution of volcanic glass sources in northeast China during the Holocene. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 971–982 (2013).

Perreault, C. et al. Characterization of obsidian from the Tibetan Plateau by XRF and NAA. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 5, 392–399 (2016).

Inizan, M.-L., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche, H. & Tixier, J. Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone (CREP, 1999).

Debénath, A. & Dibble, H. L. Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe (Univ. Pennsylvania Museum, 1994).

Semenov, S. A Prehistoric Technology: An Experimental Study of the Oldest Tools and Artefacts from Traces of Manufacture and Wear (Cory, Adams and Mackay, 1964).

Hayden, B. (ed.) Lithic Use-Wear Analysis (Academic Press, 1979).

Keeley, L. H. Experimental Determination of Stone Tool Uses: A Microwear Analysis (Univ. Chicago Press, 1980).

Vaughan, P. C. Use-Wear Analysis of Flaked Stone Tools (Univ. Arizona Press, 1985).

Knutsson, K. Patterns of Tool Use: Scanning Electron Microscopy of Experimental Quartz Tools (Societas Archaeologica Upsalensis, 1988).

González, J. E. & Ibáñez, J. J. Metodología de Análisis Funcional de Instrumentos Tallados en Sílex (Univ. Deusto, 1994).

Levi Sala, I. A Study of Microscopic Polish on Flint Implements (Tempus Reparatum, 1996).

Odell, G. H. Toward a more behavioral approach to archaeological lithic concentrations. Am. Antiq. 45, 404–431 (1980).

Odell, G. H. The mechanics of use-breakage of stone tools: some testable hypotheses. J. Field Archaeol. 8, 197–209 (1981).

Rots, V. Prehension and Hafting Traces on Flint Tools: A Methodology (Leuven Univ. Press, 2010).

Stordeur, D. Manches et emmanchements préhistoriques: quelques propositions préliminaires. MOM Éd. 15, 11–34 (1987).

Tomasso, S., Cnuts, D., Mikdad, A. & Rots, V. Changes in hafting practices during the Middle Stone Age at Ifri n’Ammar. Quat. Int. 555, 21–32 (2020).

Barham, L. From Hand to Handle: The First Industrial Revolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Ollé, A. et al. Microwear features on vein quartz, rock crystal and quartzite: a study combining optical light and scanning electron microscopy. Quat. Int. 424, 154–170 (2016).

Martín-Viveros, J. I. et al. Use-wear analysis of a specific mobile toolkit from the Middle Palaeolithic site of Abric Romaní (Barcelona, Spain): a case study from level M. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 16 (2020).

Pedergnana, A. & Ollé, A. Building an experimental comparative reference collection for lithic micro-residue analysis based on a multi-analytical approach. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 25, 117–154 (2018).

Bunn, H. et al. FxJj50: an Early Pleistocene site in northern Kenya. World Archaeol. 12, 109–136 (1980).

Blumenschine, R. J. Percussion marks, tooth marks, and experimental determination of the timing of hominid and carnivore access to long bones at FLK Zinjanthropus, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. J. Hum. Evol. 29, 21–51 (1995).

Binford, L. R. Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myths (Academic Press, 1981).

Shipman, R. Life History of a Fossil: An Introduction to Taphonomy and Paleoecology (Harvard Univ. Press, 1981).

Bunn, H. T. Meat-Eating and Human Evolution: Studies on the Diet and Subsistence Patterns of Plio-Pleistocene Hominids in East Africa. PhD dissertation, Univ. California, Berkeley (1982).

Fisher, J. W. FisherBone surface modifications in zooarchaeology. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2, 7–68 (1995).

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., de Juana, S., Galán, A. & Rodríguez, M. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2643–2654 (2009).

Blumenschine, R. J. An experimental model on the timing of hominid and carnivore influence on archaeological bone assemblages. J. Archaeol. Sci. 15, 483–502 (1988).

Blumenschine, R. & Selvaggio, M. Percussion marks on bone surfaces as a new diagnostic of hominid behaviour. Nature 333, 763–765 (1988).

Pickering, T. R. & Egeland, P. C. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 459–469 (2006).

Galán, A. B. et al. A new experimental study on percussion marks and notches and their bearing on the interpretation of hammerstone-broken faunal assemblages. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 776–784 (2009).

Johnson, E. Current developments in bone technology. Adv. Archaeol. Method Theory 8, 157–235 (1985).

Villa, P. & Mahieu, E. Breakage patterns of human long bone. J. Hum. Evol. 21, 776–784 (1991).

Capaldo, S. D. & Blumenschine, J. B. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammerstone percussion and carnivore gnawing on bovid long bones. Am. Antiq. 59, 724–748 (1994).

Miller, J. M., Keller, H. M., Heckel, C., Kaliba, P. M. & Thompson, J. C. Approaches to land snail shell bead manufacture in the Early Holocene of Malawi. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 37 (2021).

Raad, D. R. & Makarewicz, C. A. Application of XRD and digital optical microscopy to investigate lapidary technologies in Pre-Pottery Neolithic societies. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 23, 731–745 (2019).

Gurova, M., Bonsall, C., Bradley, B. & Anastassova, E. Approaching prehistoric skills: experimental drilling in the context of bead manufacturing. Bulg. e-J. Archaeol. 3, 201–221 (2013).

Falci, C. G., Cuisin, J., Delpuech, A., Van Gijn, A. & Hofman, C. L. New insights into use-wear development in bodily ornaments through the study of ethnographic collections. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 26, 755–805 (2019).

Wei, Y., d’Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., Li, F. & Gao, X. An early instance of Upper Palaeolithic personal ornamentation from China: the freshwater shell bead from Shuidonggou 2. PLoS ONE 11, e0155847 (2016).

Wei, Y. et al. A technological and morphological study of Late Paleolithic ostrich eggshell beads from Shuidonggou, North China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 85, 83–104 (2017).

d’Errico, F. et al. Trajectories of cultural innovation from the Middle to Later Stone Age in Eastern Africa: personal ornaments, bone artifacts, and ocher from Panga ya Saidi, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 141, 102737 (2020).

Dayet, L., Erasmus, R., Val, A., Feyfant, L. & Porraz, G. Beads, pigments and early Holocene ornamental traditions at Bushman rock shelter, South Africa. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 13, 635–651 (2017).

Dayet, L. et al. Revisiting the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic archaeology of Gruta do Caldeirão (Tomar, Portugal). PLoS ONE 16, e0259089 (2021).

van Gijn, A. in Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia (eds Louwe, K. L. P. & Jongste, P. F. B.) 195–205 (Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden Univ., 2006).

Van Gijn, A. L. et al. Beads and pendants of amber and jet. Nederlandse Archeol. Rapp. 47, 119–128 (2014).

Vanhaeren, M., d’Errico, F., Van Niekerk, K. L., Henshilwood, C. S. & Erasmus, R. M. Thinking strings: additional evidence for personal ornament use in the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 64, 500–517 (2013).

Strafella, A. et al. Micromorphologies of amber beads: manufacturing and use-wear traces as indicators of the artefacts’ biography. Praehist. Z. 92, 144–160 (2017).

Symes, S. A., L’Abbé, E. N., Stull, K. E., La Croix, M. & Pokines, J. T. Taphonomy and the Timing of Bone Fractures in Trauma Analysis: Manual of Forensic Taphonomy (CRC, 2013).

Backwell, L. R. & d’Errico, F. The first use of bone tools: a reappraisal of the evidence from Olduvai Gorge. Tanzan. Palaeontol. Afr. 40, 95–158 (2004).

Cignoni, M. P. et al. MeshLab: an open-source mesh processing tool. In Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference (eds Scarano, V. et al.) 129–136 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank N.-R. Lin (Department of Archaeology of Graduate School of Arts and Letters, Tohoku University) for assistance with figure preparation. We thank Y.-M. Hou and S.-X. Jiang from the IVPP for help with the micro-CT scan and reconstruction. We thank Y. Cao and D.-J. Wang from the College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, for help with the Raman analysis. Financial support for this research was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 41888101, 42071003, 42177424, 41977380, 41977379 and 42072212; S.-X.Y., J.-F.Z., C.-L.D. and K.-L.Z.), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2020YFC1521500; S.-X.Y.), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. 2020074; S.-X.Y.), the International Partnership Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. 052GJHZ2022024FN; S.-X.Y., M.P., F.d.E. and A.O.), the Key Research Program of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. IGGCAS-201905; S.-X.Y.), the Major Project of the Key Research Base for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education (grant no. 22JJD780005; J.-F.Z.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. E2E40409X2; Y.-X.Z.), the National Social Science Fund of China (grant nos 20VJXG018 and 21BKG005; W.-G.L.), the Beijing Social Science Fund Project (grant no. 21DTR046; W.-G.L.), Griffith University (S.-X.Y. and M.P.), the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme (SFF Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour—SapienCE, project no. 262618; F.d.E.), the Talents programme of the University of Bordeaux Initiative d’Excellence (grant no. 191022_001; F.d.E.), the Grand Programme de Recherche ‘Human Past’ of the Initiative d’Excellence of the same university, the European Research Council under the Horizon 2020 programme (QUANTA project, contract no. 951388; F.d.E.), Spanish MICIN/Feder (grant no. PID2021-122355NB-C32; A.O.), the Catalan AGAUR (grant no. 2021SGR-01239; A.O.) and the Univ. Rovira i Virgili (grant no. 2021-PFR-URV-126; A.O.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-X.Y., J.-F.Z., C.-L.D., F.d.E. and M.P. obtained funding and initiated the project. S.-X.Y., J.-F.Z., Y.-J.G., W.-W.H., J.-M.S., B.-Y.Y. and Y.-R.W. conducted the fieldwork and site sampling. J.-F.Z., R.W., Y.-J.G., L.-P.Z., K.-L.Z. and C.-L.D. conducted the stratigraphic, dating and palaeoenvironmental studies. W.-G.L. and Y.-X.Z. analysed the source of the raw materials. S.-X.Y., J.-P.Y., H.W., F.-X.H., Y.-R.W., Y.-M.H., M.P. and A.O. analysed the stone artefacts. Y.Z. conducted the zooarchaeological analysis. F.d.E. and A.Q. analysed the stone disc. F.d.E. and E.R. analysed the bone tool. S.-X.Y., J.-F.Z., F.d.E. and M.P. wrote the main text and supplementary materials with specialist contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of the radiocarbon dates of the IUP sites in 2 Altai (Russia), Mongolia and North China.

The ages (n = 55) of some IUP sites in the Altai and in northern Mongolia, such as Denisova, Kara-Bom, and Tolbor 16 are similar to or older than Shiyu (with the modeled age of 44.8 ± 1.2 ka). The sites in southern Mongolia are relatively younger; the oldest samples are from Layers 7 and 9 of the Orkhon 7 site, with radiocarbon ages of 43.5 ± 1.2 and 43.4 ± 1.0 cal ka BP. For the Shuidonggou (SDG) Locality 1 site, only three samples from cultural layers were radiocarbon determined, with ages of 20.2 ± 0.6, 29.8 ± 1.6 and 41.2 ± 0.2 cal ka BP, respectively, which are younger than Shiyu. Therefore, we deduced that Shiyu is the oldest IUP site in China, even compared with the IUP sites in south Mongolia, based on radiocarbon dates. Shiyu is the oldest IUP site in China, even compared with the IUP sites in south Mongolia, based on radiocarbon dates.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Location of Shiyu in the Nihewan Basin.

a, location of Shiyu and other key Palaeolithic sites dated to marine isotope stage (MIS) 3 (DEM with a resolution of 12.5 m was downloaded from https://search.asf.alaska.edu). b and c, geographic position of Shiyu and surrounding landscapes (map in panel b is made by DEM data with a resolution of 5 m from https://search.asf.alaska.edu).

Extended Data Fig. 3 The cut-marked bones and radiocarbon dating results.

a, 22SY-44 (OxA-43265), shaft fragment of a large-sized animal (most probably Equus sp.) with a set of cut marks oriented obliquely to the long axis of the bone (photoed by authors); b, 22SY-143 (Ox-43266), shaft fragment of a large-sized animal with series of cut marks parallel to the long axis; c, 22sy-282 (Ox-43267-22sy-282), bone fragment of a large-sized animal with cut marks perpendicular to the long axis; d, The radiocarbon ages obtained on the three cut-marked bones from the Shiyu site.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Scatterplot of Rb, Sr, and Zr measurements for the Shiyu obsidian artefacts and obsidian sources across Eastern Asia.

a-c, comparison of trace element (Rb, Sr, and Zr) content for four obsidian artefacts from Shiyu with volcanic glass sources in China and Far East Siberia71,72. d, the four obsidian lithics from Shiyu. Comparison of trace elements (Rb, Sr, and Zr) for four obsidian artefacts from Shiyu and volcanic glass sources in northeast China and Far East Siberia indicate that the source of artefact SY-315 is located in the Changbai Mountain, Northeast China. Artefacts SY-56, SY-316. SY-226 derive from Gladkaya, Far East Siberia. The Shiyu specimens markedly differ from samples in Tibet (NE Obsidian A, B, C and SW Obsidian A, B.)72. The ‘A1, A2, A3 source of Changbai Mountain’ set consists of data from 27, 18, 14 specimens respectively; the ‘Russian basaltic and Gladkaya’ set consists of data from 82 and 22 specimens respectively; the ‘Jiutai, Laoheishan and Jingpohu’ set consists of data from 7, 14 and 11 specimens respectively; the ‘NE Obsidian A, NE Obsidian B, NE Obsidian C, SW Obsidian A and SW Obsidian B’ set consists of data from 9, 1, 3, 28 and 7 specimens respectively. The reference data are from 13 different areas from within and external to China, with 243 specimens forming the background data.

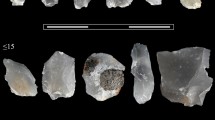

Extended Data Fig. 5 Tool types and lithic byproducts from Shiyu.

a, products from Levallois and blade reduction sequences. 1, 2, 4, Levallois points with well prepared platforms, or ‘chapeau de gendarme’ platforms; 3, Levallois flake (side flake from a Levallois core); 5, crested blade; 6, 7, broken blades; b, tools. 1-4, tanged tools; 5-6, broken tanged tools; 7, notch; 8, borer; 9, 12, denticulates; 10-11, scrapers.

Extended Data Fig. 6 20SY-362, a used Levallois point (46.23×28.83×9.93 mm).

a-b, detail of the distal edge damage: step-hinge termination on the ventral face with opposing initiation on the tip (5X, 10X) burin-like fracture. c, hafting scar from binding contact around the haft limit on the ventral right medial edge (50X). d, bright spots at the end of step-hinge of the distal edge damage. e-g, hafting bright spot on the ventral right and left proximal edge. h-i, hafting bright spot on the ventral right and left proximal edges (100X).

Extended Data Fig. 7 SY20-02, Tanged tool made on chert flake (43.15×26.58×8.81 mm).

a-c, isolated micro-scarring interpreted as binding scars, around the haft limit on the ventral right medial edge (20X, 30X). d, hafting bright spot on the dorsal medial ridge (50X). e, hafting bright spot on the proximal edge (100X). f, g, invasive soft animal mater polish covering the tool edge (50X).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Technological analysis and Raman analysis of the Shiyu disc.

a, Raman spectrum (RAM292) of the disc surface showing bands typical of graphite. b, positioning, in red, of quantitative values extracted from the RAM292 spectrum within a metamorphic gradient (modified from Fig. 8 of Beyssac)36, indicating that the carbon material used for the production of the disc was submitted to a medium to high degree of metamorphism. c, drawing summarising results of the disc analysis: 1, areas covered by labels and varnish; 2, areas abraded on a grindstone and smoothed by use wear and curatorial handling; 3, facet abraded on a grindstone; 4, fractures developed following clivage planes of the raw material; 5, surface of the perforation; 6, unmodified surface; 7, striations left by grinding indicating the direction of the grinding motion. d, microscopic analysis of the Shiyu disc.1-4, close-up view of the perforation and surrounding areas with location of the micrographs presentedNotice the blunt shiny appearance of the perforation and the palimpsest of randomly oriented striations of different size and length covering the surface, interpreted as resulting from wear and curatorial handling.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Bone tool from Shiyu.

a–c, Photograph, 3D model and drawing of different aspects of a bone tool shaped by knapping. Patterns in c identify flake scars (I), spiral fracture (II), unmodified cortical bone (III), and (IV) limits between these areas. Scale = 1 cm. d, Correlation between the length of Shiyu diaphyesal fragments bearing spiral fractures and the number of flake scars occurring on them compared with the artefact interpreted as bone tool highlights the object stands out for its small size and very large number of flake scars. e, Perspective rendering of the bone tool showing the segmented vascular canals (red). f, g, The two planes correspond to the transverse section (red: f) and the longitudinal section (green: g) of the bone tool. Most of the vascular canals are longitudinally oriented as shown by their circularity when viewed in cross section. Radial anastomoses can be observed in the two sections and appear elongated in transverse section (f) and round in the longitudinal plane (g) (white arrows). The longitudinal vascular canals are organized in circular row and circumferential lamellae are discernible in the subperiosteal region (below the red dotted line in f). Secondary osteons delimited by a cement line are scarce and in less mineralized areas (f and g, arrowheads). The CT images also reveal the presence of diagenetic alteration such as microcracks and inclusion of denser (brighter) particles lying mainly inside the bone empty spaces, namely the vascular canals (blue arrows).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information sections A–I.

Supplementary Video 1

Micro-CT images of the shaped bone tool.

Supplementary Table 1

Basic measurements and raw material types of the lithic assemblage.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, SX., Zhang, JF., Yue, JP. et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic material culture by 45,000 years ago at Shiyu in northern China. Nat Ecol Evol 8, 552–563 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02294-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02294-4

This article is cited by

-

Modern humans in Northeast Asia

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

The Persian plateau served as hub for Homo sapiens after the main out of Africa dispersal

Nature Communications (2024)