Abstract

The current biodiversity crisis underscores the need to understand how biodiversity loss affects ecosystem function in real-world ecosystems. At any one place and time, a few highly abundant species often provide the majority of function, suggesting that function could be maintained with relatively little biodiversity. However, biodiversity may be critical to ecosystem function at longer timescales if different species are needed to provide function at different times. Here we show that the number of wild bee species needed to maintain a threshold level of crop pollination increased steeply with the timescale examined: two to three times as many bee species were needed over a growing season compared to on a single day and twice as many species were needed over six years compared to during a single year. Our results demonstrate the importance of pollinator biodiversity to maintaining pollination services across time and thus to stable agricultural output.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used to generate the results of this study have been deposited in Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20083916, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20010191, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20010179). The bee specimens on which the data are based are permanently housed at Rutgers University and University of California, Davis.

Code availability

The R code used to generate the results of this study is available on GitHub (https://github.com/nlemanski/Bee_diversity_ecosystem_function).

References

Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486, 59–67 (2012).

Hooper, D. U. et al. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486, 105–108 (2012).

Potts, S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–353 (2010).

Kennedy, C. M. et al. A global quantitative synthesis of local and landscape effects on wild bee pollinators in agroecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 16, 584–599 (2013).

Cameron, S. A. et al. Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 662–667 (2011).

Xu, S. et al. Species richness promotes ecosystem carbon storage: evidence from biodiversity-ecosystem functioning experiments. Proc. Biol. Sci. 287, 20202063 (2020).

Jochum, M. et al. The results of biodiversity–ecosystem functioning experiments are realistic. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1485–1494 (2020).

Isbell, F. et al. High plant diversity is needed to maintain ecosystem services. Nature 477, 199–202 (2011).

Barnes, A. D. et al. Species richness and biomass explain spatial turnover in ecosystem functioning across tropical and temperate ecosystems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 371, 20150279 (2016).

Manning, P. & Cutler, G. C. Ecosystem functioning is more strongly impaired by reducing dung beetle abundance than by reducing species richness. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 264, 9–14 (2018).

van der Plas, F. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in naturally assembled communities. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 94, 1220–1245 (2019).

Blüthgen, N. & Klein, A.-M. Functional complementarity and specialisation: the role of biodiversity in plant–pollinator interactions. Basic Appl. Ecol. 12, 282–291 (2011).

Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: a mechanistic model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5632–5636 (1998).

Loreau, M. et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294, 804–808 (2001).

Tilman, D. The ecological consequences of changes in biodiversity: a search for general principles. Ecology 80, 1455–1474 (1999).

Duffy, J. E., Godwin, C. M. & Cardinale, B. J. Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature 549, 261–264 (2017).

Gonzalez, A. et al. Scaling-up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research. Ecol. Lett. 23, 757–776 (2020).

Garibaldi, L. A. et al. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 340, 1608–1611 (2013).

Greenop, A., Woodcock, B. A., Wilby, A., Cook, S. M. & Pywell, R. F. Functional diversity positively affects prey suppression by invertebrate predators: a meta-analysis. Ecology 99, 1771–1782 (2018).

McGill, B. J. et al. Species abundance distributions: moving beyond single prediction theories to integration within an ecological framework. Ecol. Lett. 10, 995–1015 (2007).

Genung, M. A. et al. The relative importance of pollinator abundance and species richness for the temporal variance of pollination services. Ecology 98, 1807–1816 (2017).

Winfree, R., Fox, J. W., Williams, N. M., Reilly, J. R. & Cariveau, D. P. Abundance of common species, not species richness, drives delivery of a real-world ecosystem service. Ecol. Lett. 18, 626–635 (2015).

Kleijn, D. et al. Delivery of crop pollination services is an insufficient argument for wild pollinator conservation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7414 (2015).

Smith, M. D. & Knapp, A. K. Dominant species maintain ecosystem function with non-random species loss. Ecol. Lett. 6, 509–517 (2003).

Lohbeck, M., Bongers, F., Martinez-Ramos, M. & Poorter, L. The importance of biodiversity and dominance for multiple ecosystem functions in a human-modified tropical landscape. Ecology 97, 2772–2779 (2016).

Balvanera, P., Kremen, C. & Martínez-Ramos, M. Applying community structure analysis to ecosystem function: examples from pollination and carbon storage. Ecol. Appl. 15, 360–375 (2005).

Maureaud, A. et al. Biodiversity–ecosystem functioning relationships in fish communities: biomass is related to evenness and the environment, not to species richness. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191189 (2019).

Genung, M. A., Fox, J. & Winfree, R. Species loss drives ecosystem function in experiments, but in nature the importance of species loss depends on dominance. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 1531–1541 (2020).

Potts, S. G., Vulliamy, B., Dafni, A., Ne’eman, G. & Willmer, P. Linking bees and flowers: how do floral communities structure pollinator communities? Ecology 84, 2628–2642 (2003).

Tilman, D., Isbell, F. & Cowles, J. M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 45, 471–493 (2014).

Craven, D. et al. A cross-scale assessment of productivity–diversity relationships. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 1940–1955 (2020).

Thompson, P. L., Isbell, F., Loreau, M., O’Connor, M. I. & Gonzalez, A. The strength of the biodiversity–ecosystem function relationship depends on spatial scale. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285, 20180038 (2018).

Qiu, J. & Cardinale, B. J. Scaling up biodiversity–ecosystem function relationships across space and over time. Ecology 101, e03166 (2020).

Winfree, R. et al. Species turnover promotes the importance of bee diversity for crop pollination at regional scales. Science 359, 791–793 (2018).

Albrecht, J. et al. Species richness is more important for ecosystem functioning than species turnover along an elevational gradient. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1582–1593 (2021).

Yachi, S. & Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: the insurance hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1463–1468 (1999).

Shanafelt, D. W. et al. Biodiversity, productivity, and the spatial insurance hypothesis revisited. J. Theor. Biol. 380, 426–435 (2015).

Naeem, S. & Li, S. Biodiversity enhances ecosystem reliability. Nature 390, 507–509 (1997).

Tilman, D. Biodiversity: population versus ecosystem stability. Ecology 77, 350–363 (1996).

Herrera, C. M. Variation in mutualisms: the spatiotemporal mosaic of a pollinator assemblage. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 35, 95–125 (1988).

McCormack, M. L., Adams, T. S., Smithwick, E. A. H. & Eissenstat, D. M. Variability in root production, phenology, and turnover rate among 12 temperate tree species. Ecology 95, 2224–2235 (2014).

Wright, K. W., Vanderbilt, K. L., Inouye, D. W., Bertelsen, C. D. & Crimmins, T. M. Turnover and reliability of flower communities in extreme environments: insights from long-term phenology data sets. J. Arid Environ. 115, 27–34 (2015).

Tylianakis, J. M. et al. Resource heterogeneity moderates the biodiversity-function relationship in real world ecosystems. PLoS Biol. 6, e122 (2008).

Kremen, C. Managing ecosystem services: what do we need to know about their ecology? Ecol. Lett. 8, 468–479 (2005).

Iserbyt, S. & Rasmont, P. The effect of climatic variation on abundance and diversity of bumblebees: a ten years survey in a mountain hotspot. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 48, 261–273 (2012).

Houlahan, J. E. et al. Compensatory dynamics are rare in natural ecological communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3273–3277 (2007).

Ernest, S. K. M. & Brown, J. H. Homeostasis and compensation: the role of species and resources in ecosystem stability. Ecology 82, 2118–2132 (2001).

Kremen, C., Williams, N. M. & Thorp, R. W. Crop pollination from native bees at risk from agricultural intensification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16812–16816 (2002).

Allan, E. et al. More diverse plant communities have higher functioning over time due to turnover in complementary dominant species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17034–17039 (2011).

Tilman, D., Reich, P. B. & Knops, J. M. H. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. Nature 441, 629–632 (2006).

Awasthi, A., Singh, M., Soni, S. K., Singh, R. & Kalra, A. Biodiversity acts as insurance of productivity of bacterial communities under abiotic perturbations. ISME J. 8, 2445–2452 (2014).

Tuck, S. L. et al. The value of biodiversity for the functioning of tropical forests: Insurance effects during the first decade of the Sabah biodiversity experiment. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283, 20161451 (2016).

Isbell, F. et al. Quantifying effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning across times and places. Ecol. Lett. 21, 763–778 (2018).

Reich, P. B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss escalate through time as redundancy fades. Science 336, 589–592 (2012).

Perry, C. J., Søvik, E., Myerscough, M. R. & Barron, A. B. Rapid behavioral maturation accelerates failure of stressed honey bee colonies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3427–3432 (2015).

Benjamin, F. E. & Winfree, R. Lack of pollinators limits fruit production in commercial blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Environ. Entomol. 43, 1574–1583 (2014).

Isaacs, R. & Kirk, A. K. Pollination services provided to small and large highbush blueberry fields by wild and managed bees. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 841–849 (2010).

Zhang, Y., Chen, H. Y. H. & Reich, P. B. Forest productivity increases with evenness, species richness and trait variation: a global meta-analysis. J. Ecol. 100, 742–749 (2012).

Baumgärtner, S. The insurance value of biodiversity in the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Resour. Model. 20, 87–127 (2007).

Manning, P. et al. in Advances in Ecological Research (eds Eisenhauer, N., Bohan, D. A. & Dumbrell, A. J.) 323–356 (Academic Press, 2019).

Naeem, S. Species redundancy and ecosystem reliability. Conserv. Biol. 12, 39–45 (1998).

CaraDonna, P. J. et al. Interaction rewiring and the rapid turnover of plant–pollinator networks. Ecol. Lett. 20, 385–394 (2017).

Gonzalez, A. & Loreau, M. The causes and consequences of compensatory dynamics in ecological communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40, 393–414 (2009).

Liu, D., Chang, P.-H. S., Power, S. A., Bell, J. N. B. & Manning, P. Changes in plant species abundance alter the multifunctionality and functional space of heathland ecosystems. New Phytol. 232, 1238–1249 (2021).

Buschke, F. T., Hagan, J. G., Santini, L. & Coetzee, B. W. T. Random population fluctuations bias the Living Planet Index. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1145–1152 (2021).

Almond, R. E. A., Grooten, M. & Peterson, T. Living Planet Report 2020: Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss (World Wildlife Fund, 2020).

Collen, B. et al. Monitoring change in vertebrate abundance: the Living Planet Index. Conserv. Biol. 23, 317–327 (2009).

Wagner, D. L. Insect declines in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65, 457–480 (2020).

Stanghellini, M. S., Ambrose, J. T. & Schultheis, J. R. The effects of honey bee and bumble bee pollination on fruit set and abortion of cucumber and watermelon. Am. Bee. J. 137, 386–391 (1997).

Winfree, R., Williams, N. M., Dushoff, J. & Kremen, C. Native bees provide insurance against ongoing honey bee losses. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1105–1113 (2007).

Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Kleijn, D., van der Putten, W. H. & Marini, L. Pollination contribution to crop yield is often context-dependent: a review of experimental evidence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 280, 16–23 (2019).

Stanghellini, M. S., Ambrose, J. T. & Schultheis, J. R. Seed production in watermelon: a comparison between two commercially available pollinators. HortScience 33, 28–30 (1998).

Reilly, J. R. et al. Crop production in the USA is frequently limited by a lack of pollinators. Proc. Biol. Sci. 287, 20200922 (2020).

Greenleaf, S. S. & Kremen, C. Wild bees enhance honey bees’ pollination of hybrid sunflower. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13890–13895 (2006).

Sáez, A. Managed honeybees decrease pollination limitation in self-compatible but not in self-incompatible crops. Proc. Biol. Sci. 289, 20220086 (2022).

Brittain, C., Williams, N., Kremen, C. & Klein, A. M. Synergistic effects of non-Apis bees and honey bees for pollination services. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280, 20122767 (2013).

Aizen, M. A. & Harder, L. D. The global stock of domesticated honey bees is growing slower than agricultural demand for pollination. Curr. Biol. 19, 915–918 (2009).

Houlahan, J. E. et al. Negative relationships between species richness and temporal variability are common but weak in natural systems. Ecology 99, 2592–2604 (2018).

Winfree, R. Global change, biodiversity, and ecosystem services: what can we learn from studies of pollination? Basic Appl. Ecol. 14, 453–460 (2013).

Greenleaf, S. S., Williams, N. M., Winfree, R. & Kremen, C. Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia 153, 589–596 (2007).

Cariveau, D. P., Williams, N. M., Benjamin, F. E. & Winfree, R. Response diversity to land use occurs but does not consistently stabilise ecosystem services provided by native pollinators. Ecol. Lett. 16, 903–911 (2013).

Gamfeldt, L., Hillebrand, H. & Jonsson, P. R. Multiple functions increase the importance of biodiversity for overall ecosystem functioning. Ecology 89, 1223–1231 (2008).

Zavaleta, E. S., Pasari, J. R., Hulvey, K. B. & Tilman, G. D. Sustaining multiple ecosystem functions in grassland communities requires higher biodiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1443–1446 (2010).

Haupt, R. L. & Haupt, S. E. Practical Genetic Algorithms (Wiley, 2004).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lüdecke, D., Makowski, D., Waggoner, P. & Patil, I. performance: Assessment of regression models performance. R package version 0.7.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3952174 (2020).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S (Springer, 2002).

Brooks, M. et al. glmmTMB: Generalized linear mixed models using template model builder. R package version 1.1.3 https://glmmtmb.github.io/glmmTMB/ (2022).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) DEB no. 2019863 to R.W., NSF DEB no. 1556885 to N.M.W. and U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Agriculture and Food Research Initiative no. 65104-05782 to R.W. (principal investigator) and N.M.W. (co-principal investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.J.L., N.M.W. and R.W. conceived the research question and study design. N.M.W. and R.W. oversaw data collection. N.J.L. performed the analyses and wrote the original manuscript draft. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Marcelo Aizen, Amy Iler and Joanne Bennett for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

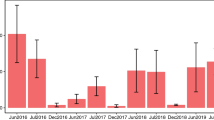

Extended Data Fig. 1 Minimum set analysis on a subsample of the data in which 30 individuals were randomly drawn each different date within a site-year.

We compared the results (dashed blue line) to a null model (solid red line) in which subsamples of 30 individuals were all drawn from the same date. Shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals across 100 replicates of the sampling process. Each point represents the mean across all replicates for a single site-year. The difference between the endpoints of the observed and null accumulation curves represents the increase in the minimum set that is due to turnover across days within a year.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Minimum set analysis on a subsample of the data in which 30 individuals were randomly drawn from each different year within a site.

We compared the results (dashed blue line) to a null model (solid red line) in which subsamples of 30 individuals were all drawn from the same year. Thus, confidence intervals include both variation across sites in the number of bee species needed, and uncertainty from the sampling process. Specifically, shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals across 100 replicates of the sampling process. Each point represents the mean across all replicates for a single site. The difference between the endpoints of the observed and null accumulation curves represents the increase in number of species needed that is due to turnover in species composition across years.

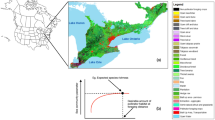

Extended Data Fig. 3 Phenological windows of bee species observed at eastern watermelon farms.

Horizontal lines show the timing of peak abundance for each bee species observed at the eastern watermelon farms. Phenological data is based on all observations of that species across all datasets collected by the lab. Comparable data for species visiting western watermelon farms was not available.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Phenological windows of bee species observed at blueberry farms.

Horizontal lines show the timing of peak abundance for each bee species observed at the blueberry farms. Phenological data is based on all observations of that species across all datasets collected by the lab.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sensitivity analysis of the effect of function threshold on the number of bee species needed for analyses done across the growing season within one year.

The function threshold is a percentage of the mean observed pollination per site-date, averaged across all site-dates.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Sensitivity analysis of the effect of function threshold on the number of bee species needed for analyses done across years.

The function threshold is a percentage of the mean observed pollination per site-date, averaged across all site-dates.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lemanski, N.J., Williams, N.M. & Winfree, R. Greater bee diversity is needed to maintain crop pollination over time. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1516–1523 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01847-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01847-3