Abstract

The standard cosmological model predicts that galaxies are built through hierarchical assembly on cosmological timescales1,2. The Milky Way, like other disk galaxies, underwent violent mergers and accretion of small satellite galaxies in its early history. Owing to Gaia Data Release 23 and spectroscopic surveys4, the stellar remnants of such mergers have been identified5,6,7. The chronological dating of such events is crucial to uncover the formation and evolution of the Galaxy at high redshift, but it has so far been challenging due to difficulties in obtaining precise ages for these oldest stars. Here we combine asteroseismology—the study of stellar oscillations—with kinematics and chemical abundances to estimate precise stellar ages (~11%) for a sample of stars observed by the Kepler space mission8. Crucially, this sample includes not only some of the oldest stars that were formed inside the Galaxy but also stars formed externally and subsequently accreted onto the Milky Way. Leveraging this resolution in age, we provide compelling evidence in favour of models in which the Galaxy had already formed a substantial population of its stars (which now reside mainly in its thick disk) before the infall of the satellite galaxy Gaia-Enceladus/Sausage5,6 around 10 billion years ago.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All raw observational data are publicly available: Kepler light curves at https://archive.stsci.edu/kepler/publiclightcurves.html; Gaia DR2 at https://gea.esac.esa.int/archive and APOGEE DR14 may be accessed via https://www.sdss.org/dr14/. APOGEE DR14 raw data have been used in the top panels of Fig. 2. Processed data such as individual frequencies, orbital and stellar parameters are available in Supplementary Table 1 or on request. Evolutionary tracks are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4032320 and theoretical stellar models and oscillation frequencies are available on request.

Code availability

The asteroseismic modelling results were provided by the code AIMS, available at https://lesia.obspm.fr/perso/daniel-reese/spaceinn/aims/version1.3, and cross-checked using the code PARAM (http://stev.oapd.inaf.it/cgi-bin/param). The peak bagging was performed using the pipeline PBJam (https://github.com/grd349/PBjam) and the orbital parameter determination with galpy (https://www.galpy.org). The codes CLES and LOSC used for stellar evolution and adiabatic oscillation computations are not publicly available, but evolutionary tracks, structure models and oscillation files are available on reasonable request.

References

Peebles, P. J. E. Principles of Physical Cosmology (Princeton Univ. Press, 1993).

Kauffmann, G., White, S. D. M. & Guiderdoni, B. The formation and evolution of galaxies within merging dark matter haloes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 264, 201–218 (1993).

Gaia Collaboration Gaia Data Release 2. Summary of the contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A1 (2018).

Majewski, S. R. et al. The Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE). Astron. J. 154, 94 (2017).

Helmi, A. et al. The merger that led to the formation of the Milky Way’s inner stellar halo and thick disk. Nature 563, 85–88 (2018).

Belokurov, V., Erkal, D., Evans, N. W., Koposov, S. E. & Deason, A. J. Co-formation of the disc and the stellar halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 478, 611–619 (2018).

Myeong, G. C., Vasiliev, E., Iorio, G., Evans, N. W. & Belokurov, V. Evidence for two early accretion events that built the Milky Way stellar halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 488, 1235–1247 (2019).

Borucki, W. J. KEPLER mission: development and overview. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 036901 (2016).

Belokurov, V. et al. The biggest splash. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 494, 3880–3898 (2020).

Di Matteo, P. et al. The Milky Way has no in-situ halo other than the heated thick disc. Composition of the stellar halo and age-dating the last significant merger with Gaia DR2 and APOGEE. Astron. Astrophys. 632, A4 (2019).

Vincenzo, F. et al. The fall of a giant. Chemical evolution of Enceladus, alias the Gaia Sausage. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 487, L47–L52 (2019).

Miglio, A. et al. PLATO as it is: a legacy mission for galactic archaeology. Astron. Nachr. 338, 644–661 (2017).

Haywood, M. et al. In disguise or out of reach: first clues about in situ and accreted stars in the stellar halo of the Milky Way from Gaia DR2. Astrophys. J. 863, 113 (2018).

Mackereth, J. T. et al. The origin of accreted stellar halo populations in the Milky Way using APOGEE, Gaia, and the EAGLE simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 482, 3426–3442 (2019).

Grand, R. J. J. et al. The dual origin of the Galactic thick disc and halo from the gas-rich Gaia-Enceladus-Sausage merger. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 497, 1603–1618 (2020).

Schuster, W. J., Moreno, E., Nissen, P. E. & Pichardo, B. Two distinct halo populations in the solar neighborhood. III. Evidence from stellar ages and orbital parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 538, A21 (2012).

Hawkins, K., Jofré, P., Gilmore, G. & Masseron, T. On the relative ages of the α-rich and α-poor stellar populations in the Galactic halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 445, 2575–2588 (2014).

Das, P., Hawkins, K. & Jofré, P. Ages and kinematics of chemically selected, accreted Milky Way halo stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493, 5195–5207 (2020).

Gallart, C. et al. Uncovering the birth of the Milky Way through accurate stellar ages with Gaia. Nat. Astron. 3, 932–939 (2019).

Helmi, A. Streams, substructures, and the early history of the Milky Way. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 58, 205–256 (2020).

Miglio, A. et al. Galactic archaeology: mapping and dating stellar populations with asteroseismology of red-giant stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 429, 423–428 (2013).

Chaplin, W. J. & Miglio, A. Asteroseismology of solar-type and red-giant stars. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 51, 353–392 (2013).

Miglio, A. et al. Age dissection of the Milky Way discs: red giants in the Kepler field. Astron. Astrophys. 645, A85 (2021).

Reese, D. R. AIMS: Asteroseismic Inference on a Massive Scale (2016); https://ascl.net/1611.014

Hayden, M. R. et al. Chemical cartography with APOGEE: metallicity distribution functions and the chemical structure of the Milky Way disk. Astrophys. J. 808, 132 (2015).

Hayes, C. R. et al. Disentangling the galactic halo with APOGEE. I. Chemical and kinematical investigation of distinct metal-poor populations. Astrophys. J. 852, 49 (2018).

Chaplin, W. J. et al. Age dating of an early Milky Way merger via asteroseismology of the naked-eye star ν Indi. Nat. Astron. 4, 382–389 (2020).

Tolstoy, E., Hill, V. & Tosi, M. Star-formation histories, abundances, and kinematics of dwarf galaxies in the local group. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 47, 371–425 (2009).

Nissen, P. E. & Schuster, W. J. Two distinct halo populations in the solar neighborhood. Evidence from stellar abundance ratios and kinematics. Astron. Astrophys. 511, L10 (2010).

Hawkins, K., Jofré, P., Masseron, T. & Gilmore, G. Using chemical tagging to redefine the interface of the Galactic disc and halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 453, 758–774 (2015).

Fernández-Alvar, E. et al. Disentangling the Galactic halo with APOGEE. II. Chemical and star formation histories for the two distinct populations. Astrophys. J. 852, 50 (2018).

Salvadori, S. & Ferrara, A. Ultra faint dwarfs: probing early cosmic star formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 395, L6–L10 (2009).

Vincenzo, F., Matteucci, F., Vattakunnel, S. & Lanfranchi, G. A. Chemical evolution of classical and ultra-faint dwarf spheroidal galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 441, 2815–2830 (2014).

McWilliam, A., Piro, A. L., Badenes, C. & Bravo, E. Evidence for a sub-Chandrasekhar-mass type Ia supernova in the Ursa Minor dwarf galaxy. Astrophys. J. 857, 97 (2018).

Kirby, E. N. et al. Evidence for sub-Chandrasekhar type Ia supernovae from stellar abundances in dwarf galaxies. Astrophys. J. 881, 45 (2019).

Koppelman, H. H., Helmi, A., Massari, D., Price-Whelan, A. M. & Starkenburg, T. K. Multiple retrograde substructures in the Galactic halo: a shattered view of Galactic history. Astron. Astrophys. 631, L9 (2019).

Gaia Collaboration Gaia Data Release 2. Observational Hertzsprung–Russell diagrams. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A10 (2018).

Chiappini, C. et al. Young [α/Fe]-enhanced stars discovered by CoRoT and APOGEE: what is their origin? Astron. Astrophys. 576, L12 (2015).

Martig, M. et al. Young α-enriched giant stars in the solar neighbourhood. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 2230–2243 (2015).

Jofré, P. et al. Cannibals in the thick disk: the young α-rich stars as evolved blue stragglers. Astron. Astrophys. 595, A60 (2016).

Mackereth, J. T. et al. The origin of diverse α-element abundances in galaxy discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 477, 5072–5089 (2018).

Kruijssen, J. M. D. et al. Kraken reveals itself—the merger history of the Milky Way reconstructed with the E-MOSAICS simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 498, 2472–2491 (2020).

Bignone, L. A., Helmi, A. & Tissera, P. B. A Gaia-Enceladus analog in the eagle simulation: insights into the early evolution of the Milky Way. Astrophys. J. 883, L5 (2019).

Chiappini, C., Matteucci, F. & Gratton, R. The chemical evolution of the galaxy: the two-infall model. Astrophys. J. 477, 765–780 (1997).

Holtzman, J. A. et al. APOGEE Data Releases 13 and 14: data and analysis. Astron. J. 156, 125 (2018).

Brown, T. M., Latham, D. W., Everett, M. E. & Esquerdo, G. A. Kepler input catalog: photometric calibration and stellar classification. Astron. J. 142, 112 (2011).

Leung, H. W. & Bovy, J. Simultaneous calibration of spectro-photometric distances and the Gaia DR2 parallax zero-point offset with deep learning. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 489, 2079–2096 (2019).

Mackereth, J. T. & Bovy, J. Fast estimation of orbital parameters in Milky Way-like potentials. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 130, 114501 (2018).

Bovy, J. galpy: a python library for Galactic dynamics. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 216, 29 (2015).

Gravity Collaboration Detection of the gravitational redshift in the orbit of the star S2 near the Galactic centre massive black hole. Astron. Astrophys. 615, L15 (2018).

Bennett, M. & Bovy, J. Vertical waves in the solar neighbourhood in Gaia DR2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 482, 1417–1425 (2019).

Gravity Collaboration Detection of orbital motions near the last stable circular orbit of the massive black hole SgrA*. Astron. Astrophys. 618, L10 (2018).

Schönrich, R., Binney, J. & Dehnen, W. Local kinematics and the local standard of rest. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 403, 1829–1833 (2010).

Davies, G. R. & Miglio, A. Asteroseismology of red giants: from analysing light curves to estimating ages. Astron. Nachr. 337, 774 (2016).

Kallinger, T. Release note: massive peak bagging of red giants in the Kepler field. Preprint athttp://arxiv.org/abs/1906.09428 (2019).

Mosser, B. & Appourchaux, T. On detecting the large separation in the autocorrelation of stellar oscillation times series. Astron. Astrophys. 508, 877–887 (2009).

Mosser, B. et al. The universal red-giant oscillation pattern. An automated determination with CoRoT data. Astron. Astrophys. 525, L9 (2011).

Vrard, M., Mosser, B. & Samadi, R. Period spacings in red giants. II. Automated measurement. Astron. Astrophys. 588, A87 (2016).

Bedding, T. R. et al. Gravity modes as a way to distinguish between hydrogen- and helium-burning red giant stars. Nature 471, 608–611 (2011).

Mosser, B. et al. Mixed modes in red giants: a window on stellar evolution. Astron. Astrophys. 572, L5 (2014).

Montalbán, J., Miglio, A., Noels, A., Scuflaire, R. & Ventura, P. Seismic diagnostics of red giants: first comparison with stellar models. Astrophys. J. 721, L182–L188 (2010).

Yu, J. et al. Asteroseismology of 16,000 Kepler red giants: global oscillation parameters, masses, and radii. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 236, 42 (2018).

Jönsson, H. et al. APOGEE Data Releases 13 and 14: stellar parameter and abundance comparisons with independent analyses. Astron. J. 156, 126 (2018).

Lund, M. N. & Reese, D. R. Tutorial: Asteroseismic Stellar Modelling with AIMS. Astrophys. Space Sci. Proc. 49, 149–161 (2018).

Rendle, B. M. et al. AIMS—a new tool for stellar parameter determinations using asteroseismic constraints. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 484, 771–786 (2019).

Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D. & Goodman, J. emcee: the MCMC hammer. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 125, 306 (2013).

Lebreton, Y. & Goupil, M. J. Asteroseismology for ‘à la carte’ stellar age-dating and weighing. Age and mass of the CoRoT exoplanet host HD 52265. Astron. Astrophys. 569, A21 (2014).

Gough, D. O. in Progress of Seismology of the Sun and Stars (eds Osaki, Y. & Shibahashi, H.) 283–318 (Springer, 1990).

Ball, W. H. & Gizon, L. A new correction of stellar oscillation frequencies for near-surface effects. Astron. Astrophys. 568, A123 (2014).

Brown, T. M., Gilliland, R. L., Noyes, R. W. & Ramsey, L. W. Detection of possible p-mode oscillations on procyon. Astrophys. J. 368, 599 (1991).

Huber, D. et al. Testing scaling relations for solar-like oscillations from the main sequence to red giants using Kepler data. Astrophys. J. 743, 143 (2011).

Scuflaire, R. et al. CLÉS, code liégeois d’évolution stellaire. Astrophys. Space Sci. 316, 83–91 (2008).

Scuflaire, R. et al. The Liège Oscillation code. Astrophys. Space Sci. 316, 149–154 (2008).

Montalbán, J. et al. Adiabatic solar-like oscillations in red giant stars. Astrophys. Space Sci. Proc. 26, 23–32 (2012).

Handberg, R., Miglio, A., Brogaard, K., Bossini, D. & Elsworth, Y. P. Peakbagging in the open cluster NGC 6819: opening a treasure chest or Pandora’s box? Astron. Nachr. 337, 799–804 (2016).

Casagrande, L. & VandenBerg, D. A. Synthetic stellar photometry—II. Testing the bolometric flux scale and tables of bolometric corrections for the Hipparcos/Tycho, Pan-STARRS1, SkyMapper, and JWST systems. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 475, 5023–5040 (2018).

Lindegren, L. et al. Gaia Data Release 2. The astrometric solution. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A2 (2018).

Khan, S. et al. New light on the Gaia DR2 parallax zero-point: influence of the asteroseismic approach, in and beyond the Kepler field. Astron. Astrophys. 628, A35 (2019).

Hall, O. J. et al. Testing asteroseismology with Gaia DR2: hierarchical models of the red clump. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 486, 3569–3585 (2019).

Zinn, J. C., Pinsonneault, M. H., Huber, D. & Stello, D. Confirmation of the Gaia DR2 parallax zero-point offset using asteroseismology and spectroscopy in the Kepler field. Astrophys. J. 878, 136 (2019).

Green, G. M. et al. A three-dimensional map of Milky Way dust. Astrophys. J. 810, 25 (2015).

Green, G. M. Mapping Milky Way Dust in 3D with Stellar Photometry. PhD thesis, Harvard Univ. (2016).

Green, G. M., Schlafly, E., Zucker, C., Speagle, J. S. & Finkbeiner, D. A 3D dust map based on Gaia, Pan-STARRS 1, and 2MASS. Astrophys. J. 887, 93 (2019).

Rodrigues, T. S. et al. Bayesian distances and extinctions for giants observed by Kepler and APOGEE. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 445, 2758–2776 (2014).

Rodrigues, T. S. et al. Determining stellar parameters of asteroseismic targets: going beyond the use of scaling relations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 467, 1433–1448 (2017).

Paxton, B. et al. Modules for experiments in stellar astrophysics (mesa): planets, oscillations, rotation, and massive stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 208, 4 (2013).

Bressan, A. et al. PARSEC: stellar tracks and isochrones with the Padova and Trieste Stellar Evolution Code. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 427, 127–145 (2012).

Acknowledgements

J.M., J.T.M., A.M., F.V. and E.W. acknowledge support from the ERC Consolidator Grant funding scheme (project ASTEROCHRONOMETRY, G.A. no. 772293). F.V. acknowledges the support of a Fellowship from the Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics at The Ohio State University. M.V. is supported by FEDER - Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional through COMPETE2020 - Programa Operacional Competitividade e Internacionalização by grants PTDC/FIS-AST/30389/2017 and POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030389. C.C. acknowledges partial support from DFG Grant CH1188/2-1 and from the ChETEC COST Action (CA16117), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). G.B. acknowledges fundings from the SNF AMBIZIONE grant no. 185805 (Seismic inversions and modelling of transport processes in stars) and from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 833925, project STAREX). G.R.D. acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (CartographY GA 804752). M.B.N. acknowledges support from the UK Space Agency. O.J.H. acknowledges the support of the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). This article made use of AIMS, a software for fitting stellar pulsation data, developed in the context of the SPACEINN network, funded by the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme. This work has made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular, the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement. The computations described in this paper were performed using the University of Birmingham’s BlueBEAR HPC service, which provides a high-performance computing service to the university’s research community. See http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/bear for more details. We thank S. McGee for reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. led the project, with help from J.T.M., A.M., F.V., C.C. and W.J.C. G.R.D. designed the pipeline for the light-curve analysis. J.M., J.T.M., A.M., F.V., G.R.D., O.J.H., M.B.N., S.K. and W.E.v.R. worked on extracting mode parameters from the Kepler light curves. J.M., A.N. and R.S. performed the stellar modelling and theoretical oscillation frequency computations. J.M., G.B. and B.M.R. worked on the stellar parameter determination from individual frequencies using Bayesian inference code AIMS. A.M. estimated stellar parameters from global observational constraints using the code PARAM. B.M. and M.V. provided global seismic parameters. J.T.M. and F.V. performed the kinematics and chemical composition analysis from Gaia DR2 and APOGEE DR14 datasets. E.W. derived absolute stellar luminosity from Gaia DR2. J.W.F. provided radiative opacity data at low temperature for the alpha-enhanced chemical mixture used in the stellar evolution code. All authors have contributed to the interpretation of the data and the results, and discussion and giving comments on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Astronomy thanks David Soderblom and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

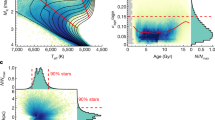

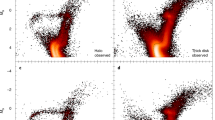

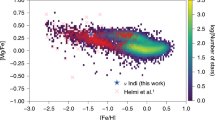

Extended Data Fig. 1 Data samples.

a, Diagram [α/Fe] versus [Fe/H] for all the Kepler-APOGEE-DR14 sample (grey dots). Orange symbols are the targets in our sub-sample: red giant stars with [Fe/H] < − 0.5, and blue ones are the first ascending red giant branch targets selected for characterization in this paper. b, Teff versus \({\nu }_{\max }\) diagram (equivalent to Kiel diagram) of our target sample (color-coded by metallicity), overlying the complete Kepler-APOGEE-DR14 one (grey empty and full symbols). The dashed lines corresponds to two [α/Fe]=0.2 evolutionary tracks: blue M=0.9 M⊙, [Fe/H]=-1.0; orange, same mass but [Fe/H]=-0.5.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Posterior probability distributions for KIC 4143467 stellar properties as inferred by AIMS.

a-f: age, mass, radius, mean density, luminosity and frequency at maximun power, respectively. The oscillation spectra of this target is shown in first panel of Fig. 1. The vertical dash-dotted lines indicate the value of the corresponding parameter in the best-fitting model from the MCMC sampling.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Posterior probability distributions for KIC 12111110 stellar properties as inferred by AIMS.

a-f: age, mass, radius, mean density, luminosity and frequency at maximun power, respectively. The vertical dash-dotted lines indicate the value of the corresponding parameter in the best-fitting model from the MCMC sampling.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Age distribution using PARAM for the APOGEE-Kepler sample with stellar radius limited to 14 R⊙.

a-b, [α/Fe] vs. [Fe/H] distribution of the sample coloured by age (a) and eccentricity (b). The symbol size scales with \({\nu }_{\max }\). c, Age distributions of accreted and in-situ stars, so classified from their [α/Fe] and eccentricity values; d, Kiel diagram of the sample coloured by metallicity. Notice that the ‘very old’ (yellow dots Teff > 5400 K) suggest that we have underestimated the mass loss for those stars.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Age distribution using PARAM for the APOGEE-Kepler sample with stellar radius limited to 8 R⊙.

a-b, [α/Fe] vs. [Fe/H] distribution of the sample coloured by age (a) and eccentricity (b). The symbol size scales with \({\nu }_{\max }\). c, Age distributions of accreted and in-situ stars, so classified from their [α/Fe] and eccentricity values; d, Kiel diagram of the sample coloured by metallicity. Notice that the ‘very old’ (yellow dots Teff > 5400 K) suggest that we have underestimated the mass loss for those stars.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Age and eccentricity distributions for different selection criteria for in-situ and accreted populations.

Age against eccentricity (e) for the stars in the sample coloured by [Fe/H]}. Circles represent age values of the best fitting models, and horizontal lines their uncertainties ([16%-84%] C.I. from full posterior distributions). Uncertainties on e are smaller than the symbol size. The diamond represents ν Indi25 (not included in the distributions). The histogram above reflects the combined posterior distributions for the stars in each selection. a,c, division line [Mg/Fe] = -0.5 [Fe/H]-0.3 (ref. 14). b,d, division line [Mg/Fe] = -0.2 [Fe/H] (ref. 26). Top and bottom panels correspond to eccentricity threshold 0.7 and 0.6 respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Probabilistic graphical model of that used to fit the mean age and intrinsic age spread of the in- and ex-situ populations defined on the basis of element abundances and orbital parameters.

We assume the measured ages are drawn from an underlying true age θ distribution that is Gaussian with a mean μ with a standard deviation τ. We assume that the true age distribution is contaminated by stars whose mass is higher than expected (and therefore appear younger), likely due to some poorly understood process such as binary interactions. We model these contaminants as also being drawn from another normal distribution with a mean μc and spread τc which has a fractional contribution ε to the total age distribution (hence the main population contributes 1 − ε).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table 1 with the stellar parameters for the final sample of 95 targets.

Supplementary Data

Machine-readable version of Supplementary Table 1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montalbán, J., Mackereth, J.T., Miglio, A. et al. Chronologically dating the early assembly of the Milky Way. Nat Astron 5, 640–647 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01347-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01347-7

This article is cited by

-

The discovery space of ELT-ANDES. Stars and stellar populations

Experimental Astronomy (2024)

-

A time-resolved picture of our Milky Way’s early formation history

Nature (2022)

-

Chemical and stellar properties of early-type dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way

Nature Astronomy (2022)