Abstract

If gamma-ray bursts are at cosmological distances, they must be gravitationally lensed occasionally1,2. The detection of lensed images with millisecond-to-second time delays provides evidence for intermediate-mass black holes, a population that has been difficult to observe. Several studies have searched for these delays in gamma-ray burst light curves, which would indicate an intervening gravitational lens3,4,5,6. Among the ~104 gamma-ray bursts observed, there have been a handful of claimed lensing detections7, but none have been statistically robust. Here we present a Bayesian analysis identifying gravitational lensing in the light curve of GRB 950830. The inferred lens mass Ml depends on the unknown lens redshift zl, and is given by \((1+z_{\rm{l}})M_{\rm{l}} = 5.{5}_{-0.9}^{+1.7}\times 1{0}^{4}\,M_{\odot}\) (90% credibility), which we interpret as evidence for an intermediate-mass black hole. The most probable configuration, with a lens redshift zl ≈ 1 and a gamma-ray burst redshift zs ≈ 2, yields a present-day number density of about \(2.{3}_{-1.6}^{+4.9}\times 1{0}^{3}\,{\text{Mpc}}^{-3}\) (90% credibility) with a dimensionless energy density \({{{\varOmega }}}_{{\rm{IMBH}}}\approx 4.{6}_{-3.3}^{+9.8}\times 1{0}^{-4}\). The false alarm probability for this detection is ~0.6% with trial factors. While it is possible that GRB 950830 was lensed by a globular cluster, it is unlikely as we infer a cosmic density inconsistent with predictions for globular clusters ΩGC ≈ 8 × 10−6 at 99.8% credibility. If a significant intermediate-mass black hole population exists, it could provide the seeds for the growth of supermassive black holes in the early Universe.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The BATSE data catalogue is available from the NASA data archive at https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/compton/data/batse/trigger. We use the ‘discsc’, ‘tte’ and ‘tte_list’ datatypes in our search. The data used in our analysis of GRB 950830 can be found at https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/compton/data/batse/trigger/03601_03800/03770_burst/tte_bfits_3770.fits.gz and https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/compton/data/batse/trigger/03601_03800/03770_burst/tte_list_3770.fits.gz. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The analysis code PyGRB55 has been written in Python56 by J.P. and is freely available at https://github.com/JamesPaynter/PyGRB under the BSD 3-Clause License. PyGRB is built around Monash University’s Bilby nested sampling wrapper, with additional FITS I/O functionality provided by AstroPy57. The software uses the NumPy58 and SciPy59 computational libraries. Plotting makes use of the Matplotlib60 and corner61 libraries62.

References

Paczynski, B. Gamma-ray bursters at cosmological distances. Astrophys. J. Lett. 308, L43–L46 (1986).

Paczynski, B. Gravitational microlensing and gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 317, L51–L55 (1987).

Wambsganss, J. A method to distinguish two gamma-ray bursts with similar time profiles. Astrophys. J. 406, 29–35 (1993).

Nowak, M. A. & Grossman, S. A. Can we identify lensed gamma-ray bursts? Astrophys. J. 435, 557–572 (1994).

Muñoz, J. B., Kovetz, E. D., Dai, L. & Kamionkowski, M. Lensing of fast radio bursts as a probe of compact dark matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 091301 (2016).

Ji, L., Kovetz, E. D. & Kamionkowski, M. Strong lensing of gamma ray bursts as a probe of compact dark matter. Phys. Rev. D 98, 123523 (2018).

Hirose, Y., Umemura, M., Yonehara, A. & Sato, J. Imprint of gravitational lensing by population III stars in gamma-ray burst light curves. Astrophys. J. 650, 252–260 (2006).

Portegies Zwart, S. F., Baumgardt, H., Hut, P., Makino, J. & McMillan, S. L. W. Formation of massive black holes through runaway collisions in dense young star clusters. Nature 428, 724–726 (2004).

Aasi, J. et al. Advanced LIGO. Class. Quantum Grav. 32, 074001 (2015).

Acernese, F. et al. Advanced Virgo: a 2nd generation interferometric gravitational wave detector. Class. Quantum Grav. 32, 024001 (2015).

Abbott, B. P. et al. Binary black hole population properties inferred from the first and second observing runs of advanced LIGO and advanced Virgo. Astrophys. J. 882, L24 (2019).

Abbott, B. P. et al. GW190521: a binary black hole merger with a total mass of 150 M⨀. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 101102 (2020).

King, A. GSN 069—a tidal disruption near miss. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493, L120–L123 (2020).

Oka, T., Tsujimoto, S., Iwata, Y., Nomura, M. & Takekawa, S. Millimetre-wave emission from an intermediate-mass black hole candidate in the Milky Way. Nat. Astron. 1, 709–712 (2017).

Takekawa, S., Oka, T., Iwata, Y., Tsujimoto, S. & Nomura, M. The fifth candidate for an intermediate-mass black hole in the Galactic Center. Astrophys. J. 890, 167 (2020).

Lin, D. et al. A luminous X-ray outburst from an intermediate-mass black hole in an off-centre star cluster. Nat. Astron. 2, 656–661 (2018).

Press, W. H. & Gunn, J. E. Method for detecting a cosmological density of condensed objects. Astrophys. J. 185, 397–412 (1973).

Fishman, G. J., Meegan, C. A., Wilson, R. B., Paciesas, W. S. & Pendleton, G. N. The BATSE experiment on the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory: status and some early results. In NASA Conference Publication Vol. 3137, 26–34 (NASA, 1992).

Costa, E. et al. Discovery of an X-ray afterglow associated with the γ-ray burst of 28 February 1997. Nature 387, 783–785 (1997).

Narayan, R. & Wallington, S. Determination of lens parameters from gravitationally lensed gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. 399, 368–372 (1992).

Mao, S. Gravitational lensing, time delay, and gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 389, L41–L44 (1992).

Krauss, L. M. & Small, T. A. A new approach to gravitational microlensing—time delays and the galactic mass distribution. Astrophys. J. 378, 22–29 (1991).

Blaes, O. M. & Webster, R. L. Using gamma-ray bursts to detect a cosmological density of compact objects. Astrophys. J. Lett. 391, L63–L66 (1992).

Geiger, B. & Schneider, P. The light-curve reconstruction method for measuring the time delay of gravitational lens systems. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 282, 530–546 (1996).

Norris, J. P. et al. Attributes of pulses in long bright gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. 459, 393–412 (1996).

Thrane, E. & Talbot, C. An introduction to Bayesian inference in gravitational-wave astronomy: parameter estimation, model selection, and hierarchical models. Pub. Astron. Soc. Aust. 36, E010 (2019).

Baumgardt, H. & Hilker, M. A catalogue of masses, structural parameters, and velocity dispersion profiles of 112 Milky Way globular clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 478, 1520–1557 (2018).

Elbert, O. D., Bullock, J. S. & Kaplinghat, M. Counting black holes: the cosmic stellar remnant population and implications for LIGO. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 473, 1186–1194 (2018).

Hurley, K. et al. A search for gravitationally lensed gamma-ray bursts in the data of the interplanetary network and konus-wind. Astrophys. J. 871, 121 (2019).

Marani, G. F., Nemiroff, R. J., Norris, J. P., Hurley, K. & Bonnell, J. T. Gravitationally lensed gamma-ray bursts as probes of dark compact objects. Astrophys. J. Lett. 512, L13–L16 (1999).

Williams, L. L. R. & Wijers, R. A. M. J. Distortion of gamma-ray burst light curves by gravitational microlensing. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 286, L11–L16 (1997).

Wyithe, J. S. B. & Turner, E. L. Gravitational microlensing of gamma-ray bursts at medium optical depth. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 319, 1163–1168 (2000).

Lewis, G. F. Gravitational microlensing time delays at high optical depth: image parities and the temporal properties of fast radio bursts. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 497, 1583–1589 (2020).

Walker, M. A. & Lewis, G. F. Nanolensing of gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. 589, 844–860 (2003).

Gould, A. Femtolensing of gamma-ray bursters. Astrophys. J. Lett. 386, L5–L7 (1992).

Nemiroff, R. J. et al. Searching gamma-ray bursts for gravitational lensing echoes—implications for compact dark matter. Astrophys. J. 414, 36–40 (1993).

Ougolnikov., O. S. A search for possible mesolensing of cosmic gamma-ray bursts: II. Double and triple bursts in the BATSE catalog. Cosmic Res. 41, 141–146 (2003).

Biltzinger, B., Kunzweiler, F., Greiner, J., Toelge, K. & MichaelBurgess, J. A physical background model for the Fermi Gamma-ray Burst Monitor. Astron. Astrophys. 640, A8 (2020).

Nemiroff, R. J. et al. Gamma-ray burst lensing limits on cosmological parameters. AIP Conf. Proc. 526, 663 (2000).

Li, C. & Li, L. Search for strong gravitational lensing effect in the current GRB data of BATSE. Sci. Chin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 57, 1592–1599 (2014).

Davidson, R., Bhat, P. N. & Li, G. Are there gravitationally lensed gamma-ray bursts detected by GBM? AIP Conf. Proc. 1358, 17 (2011).

Bagoly, Z. & Veres, P. Achromatic search for gravitational lensing in Fermi data. AIP Conf. Proc. 1279, 293 (2010).

Oguri, M. Strong gravitational lensing of explosive transients. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 126901 (2019).

Hakkila, J., Horváth, I., Hofesmann, E. & Lesage, S. Properties of short gamma-ray burst pulses from a BATSE TTE GRB pulse catalog. Astrophys. J. 855, 101 (2018).

Ashton, G. et al. Bilby: a user-friendly bayesian inference library for gravitational-wave astronomy. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 241, 27 (2019).

Skilling, J. Nested sampling. AIP Conf. Proc. 735, 395 (2004).

Skilling, J. Nested sampling for general Bayesian computation. Bayesian Anal. 1, 833–859 (2006).

Feroz, F., Hobson, M. P. & Bridges, M. MULTINEST: an efficient and robust Bayesian inference tool for cosmology and particle physics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 398, 1601–1614 (2009).

Higson, E., Handley, W., Hobson, M. & Lasenby, A. Dynamic nested sampling: an improved algorithm for parameter estimation and evidence calculation. Stat. Comput. 29, 891–913 (2019).

Speagle, J. S. DYNESTY: a dynamic nested sampling package for estimating Bayesian posteriors and evidences. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493, 3132–3158 (2020).

Band, D. et al. BATSE observations of gamma-ray burst spectra. I. Spectral diversity. Astrophys. J. 413, 281–292 (1993).

Xiao, L. & Schaefer, B. E. Redshift catalog for Swift long gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. J. 731, 103 (2011).

Paciesas, W. S. et al. The fourth BATSE gamma-ray burst catalog (revised). Astrophys. J. Suppl. 122, 465–495 (1999).

Jordán, A. et al. The ACS Virgo Cluster Survey. XII. The luminosity function of globular clusters in early-type galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 171, 101–145 (2007).

Paynter, J. R. Pygrb: a pure Python gamma-ray burst analysis package. J. Open Source Softw. 5, 2536 (2020).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F. L. Python 3 Reference Manual (CreateSpace, 2009).

Collaboration, A. et al. Astropy: a community Python package for astronomy. Astron. Astrophys. 558, A33 (2013).

van der Walt, S., Colbert, S. C. & Varoquaux, G. The numpy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 13, 22–30 (2011).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Hunter., J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Foreman-Mackey, D. corner.py: scatterplot matrices in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 1, 24 (2016).

Meade, B., Lafayette, L., Sauter, G. & Tosello, D. Spartan HPC-Cloud Hybrid: Delivering Performance and Flexibility (Univ. Melbourne, 2017); https://doi.org/10.4225/49/58ead90dceaaa

Acknowledgements

E.T. is supported through Australian Research Council grant no. CE170100004 and no. FT150100281. The analysis software was run on The University of Melbourne’s Spartan HPC system. This research has made use of data provided by the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center (HEASARC), which is a service of the Astrophysics Science Division at NASA/GSFC and the High Energy Astrophysics Division of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. J.P. acknowledges S. Wyithe, M. Trenti and A. Melatos for constructive comments in analysing and interpreting the data and results. J.P. also thanks C. Shrader for assistance in understanding the BATSE instrumentation, and J. M. Burgess for constructive feedback on PyGRB and the proper analysis of gamma-ray data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.W. contributed to the initial planning of the project with later additions from J.P. and E.T. J.P. contributed the data analysis through the pulse-fitting software package PyGRB under the guidance of E.T. The manuscript was drafted by J.P. and E.T. J.P. and R.W. contributed the gravitational lensing calculations while E.T. contributed the Bayesian framework. J.P. and E.T. responded to questions and comments from the referees. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Astronomy thanks Zsolt Bagoly, Kevin Hurley, Masamune Oguri and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The individual pulses that make up channel 1 (red: 20-60 keV) of Figure 2.

a, The solid red lines are the median of 60,000 FRED-X pulses sampled from the posterior distributions. 200 of these curves are sampled and shown in black. b, The same as a) for the sine-Gaussian residual. c, The sum of the medians of the pulses in a and b.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The individual pulses that make up channel 2 (yellow: 60-110 keV) of Figure 2.

a, The solid yellow lines are the median of ~ 60, 000 FRED-X pulses sampled from the posterior distributions. 200 of these curves are sampled and shown in black. b, The same as a) for the sine-Gaussian residual. c, The sum of the medians of the pulses in a and b.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The individual pulses that make up channel 2 (green: 110-320 keV) of Figure 2.

a, The solid green lines are the median of ~ 60, 000 FRED-X pulses sampled from the posterior distributions. 200 of these curves are sampled and shown in black. b, The same as a) for the sine-Gaussian residual. c, The sum of the medians of the pulses in a and b.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The individual pulses that make up channel 2 (blue: 320-2,000 keV) of Figure 2.

a, The solid blue lines are the median of ~ 60,000 FRED-X pulses sampled from the posterior distributions. 200 of these curves are sampled and shown in black. b, The same as a) for the sine-Gaussian residual. c, The sum of the medians of the pulses in a and b.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The Hardness-Duration plot of BATSE GRBs.

The T90 durations are taken from the BATSE data tables: https://gammaray.nsstc.nasa.gov/batse/grb/catalog/4b/index.html. We calculate the hardness ratios for each of the GRBs with a listed T90. The short γ-ray burst population is shown in purple, and the long GRB population in red. Iso-likelihood contours of a two-component Gaussian mixture model are plotted in grey. The plotted uncertainties in the hardness ratio are defined by 1- σ statistical errors on the number of counts in the numerator and denominator.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The autocorrelation of the light curve of GRB 950830.

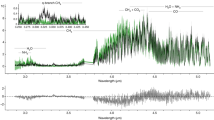

a, The sum of the four energy channels, ~ 20-2,000 keV. b, The autocorrelation function of the summed light curve, where the autocorrelation is defined in equation (6). The black dotted line is a fit to the light curve with a 3rd order Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter with a 101 bin smoothing window. The vertical red dotted line is the point of maximum deviation between the ACF and the Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter at δt= 0.390 seconds. The blue shaded regions delineate regions of 1 − σ, 3 − σ, and 5 − σ away from the Savitzky-Golay fit. The dispersion between the autocorrelation function and the fit, σ2, is defined in equation (7). c, The autocorrelation function for each of the 4 BATSE large area detector broadband energy channels. Each colour indicates a different energy channel, red: 20-60 keV, yellow: 60-110 keV, green: 110-320 keV, blue: 320-2,000 keV. The shaded regions delineate 3-σ deviance from the Savitzky-Golay fits, which are omitted for clarity.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The autocorrelation of the light curve of GRB 911031.

a, The sum of the four energy channels, 20-2,000 MeV. b, The autocorrelation function of the summed light curve, where the autocorrelation is defined in equation (6). The dotted line is a fit to the light curve with a 3rd order Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter with a 101 bin smoothing window. The blue shaded regions delineate regions of 1 − σ, 3 − σ, and 5 − σ away from the Savitzky-Golay fit. The dispersion between the autocorrelation function and the fit, σ2, is defined in equation (7). c, The light curve for each of the 4 BATSE large area detector broadband energy channels. Each colour indicates a different energy channel, red: 20-60 keV, yellow: 60-110 keV, green: 110-320 keV, blue: 320-2,000 keV. d, The autocorrelation function for each light curve channel. The shaded regions delineate 3 − σ deviance from the Savitzky-Golay fits, which are omitted for clarity.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The gravitational lens parameter posterior distributions for a model fit to GRB 911031 for each of the 4 BATSE large area detector broadband energy channels.

Each colour indicates a different energy channel, red: 20-60 keV, yellow: 60-110 keV, green: 110-320 keV, blue: 320-2,000 keV. Contours contain 39.3%. 86.4%, and 98.9% of the probability density. The light curve of GRB 911031 is shown in Extended Data Fig. 7.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Optical depth as a function of source redshift zs.

We estimate the optical depth for mean source redshifts zs=0.1: blue, zs: orange, zs=1.0: green, zs=1.34: black, zs=2.0: red, zs=5.0: purple based on Eq. (38). The median Cmax/Cmin values of 1.5, 2.2, and 2.5 taken as the magnification limit cutoff (Eq.(32)) are shown as solid, dash-dot, and dashed curves respectively. The solid black horizontal line is the estimate lens probability based on seeing one event in 2,679 light curves. The dotted black vertical line is the estimated globular cluster density, Ωgc. The dash-dot vertical black line is the naive estimate for the density Ωlens ~ τ. The calculated lens densities for each redshift are summarized in Extended Data Fig. 10.

Extended Data Fig. 10 The inferred lens densities Ωl for mean source redshift zs.

A median peak counts ratio \(\tilde{C}=2.5\) from the BATSE \({{\rm{C}}}_{\max }/{{\rm{C}}}_{\min }\) table for 1,024ms integration times is assumed. The peak count ratios are defined through \({\rm{C}}\equiv {{\rm{C}}}_{\max }/{{\rm{C}}}_{\min }\). \({{\rm{C}}}_{\max }\) is the maximum detected counts over a given integration period. \({{\rm{C}}}_{\min }\) is the minimum number of counts that would trigger the second most brightly illuminated detector at that time. Further details are given in the Methods section calculation of optical depths.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Light curve of GRB 950830 with fits.

Source Data Fig. 2

Four overlapping coloured circles and a black circle. Time delay and magnification ratio posteriors for GRB 950830.

Source Data Fig. 3

Coloured probability densities.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Red lines.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Yellow lines.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Green lines.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Blue lines.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Hardness duration plot.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Three-panel autocorrelation of GRB 950830.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Four-panel autocorrelation of GRB 911031.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Four colinear coloured circles. Magnification ratio and time delay posterior GRB 911031.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Lens probability graph.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paynter, J., Webster, R. & Thrane, E. Evidence for an intermediate-mass black hole from a gravitationally lensed gamma-ray burst. Nat Astron 5, 560–568 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01307-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01307-1

This article is cited by

-

Searching for Strong Gravitational Lenses

Space Science Reviews (2024)

-

Emulator-based Bayesian inference on non-proportional scintillation models by compton-edge probing

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Rates of compact object coalescences

Living Reviews in Relativity (2022)

-

Strong lensing time-delay cosmography in the 2020s

The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review (2022)

-

High-resolution imaging for advances in astronomy

Journal of Optics (2021)