Abstract

Changes in health insurance coverage may disrupt access to and continuity of care, even for those who remain insured. Continuity of care is especially important in schizophrenia, which requires ongoing medical and pharmaceutical treatment. However, little is known about continuity of insurance coverage among those with schizophrenia. The objective was to examine the probability of insurance transitions for individuals with schizophrenia who were continuously insured and whether this varied across insurance types. The Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database identified individuals with schizophrenia aged 18–64 who were continuously insured during a two-year period between 2014 and 2018. A logistic regression estimated the association of having an insurance transition – defined as having a change in insurance type – with insurance type at the start of the period, adjusting for age, sex, ZIP code in the lowest quartile of median income, and ZIP code with concentrated poverty. Overall, 15.1% had at least one insurance transition across a 24-month period. Insurance transitions were most frequent among those with plans from the Marketplace. In regression adjusted results, individuals covered by the traditional Medicaid program were 20.2 percentage points [pp] (95% confidence interval [CI]: 24.6 pp, 15.9 pp) less likely to have an insurance transition than those who were insured by a Marketplace plan. Insurance transitions among individuals with schizophrenia were common, with more than one in six people having at least one transition in insurance type during a two-year period. Given that even continuously insured individuals with schizophrenia commonly experience insurance transitions, attention to insurance transitions as a barrier to care access and continuity is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to care and continuity of care is important for people with schizophrenia1, which requires ongoing medical and pharmaceutical treatment. Schizophrenia is a chronic severe mental illness with an estimated prevalence between 0.25% and 0.64% in the United States (US)2. In the US, healthcare access is strongly connected to health insurance coverage3. Health insurance is a key component of timely access to care, timely diagnosis, and on-going treatment. Non-elderly adults with schizophrenia have high rates of public insurance coverage (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, or dual Medicaid and Medicare)4,5,6, but also rely on private coverage. The ACA increased insurance coverage of individuals with schizophrenia with 96% of those diagnosed with schizophrenia having insurance coverage in the 2014–2020 period5, which is a much higher rate than the overall population7.

Insurance disruptions result when individuals experience a change in their health insurance coverage type or specific insurance plan or experience a period of uninsurance. All insurance disruptions can negatively impact access to care and continuity of care for individuals, even for those who remain insured. For example, switching insurance types or insurance plans may require changing healthcare providers due to changes in the included provider network8,9. Studies have found that individuals who experience insurance disruptions – either changes in insurance type or periods of uninsurance – have worse access to care and outcomes than those who are stably insured by the same insurance type9,10,11,12,13. Prior research has shown that switching insurance type and coverage gaps, especially longer gaps, are associated with more healthcare utilization that might indicate crisis or deterioration, such as inpatient visits and emergency room visits, including among individuals with schizophrenia or serious mental illness13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Additionally, longer enrollment with an insurer may create incentives for insurers to provide better preventive care that may not have immediate impacts but be cost-saving in the future; if enrollees are frequently changing insurance types or plans, these incentives for insurers are blunted20,21.

Prior research has found that individuals with serious mental illness experience frequent insurance disruptions22,23,24, and individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to experience an insurance disruption – often a coverage gap – compared to other types of serious mental illness25. However, most studies examining insurance stability for those with schizophrenia were conducted before the ACA, limited to those with either first episode psychosis or first diagnosis of schizophrenia, or limited to young adults22,23,24. In the most closely related study, Pesa and colleagues focused on a small sample of young adults (18-34 years) in Colorado with private insurance at the start of period and a new schizophrenia diagnosis, requiring one year of observation prior to observing a diagnosis. They found that more than half of this selected sample experienced changes in insurance type over a 48-month period26. Although studies have shown that low-income adults in general are less likely to experience periods of uninsurance after the ACA27,28, much less is known about insurance stability among those who remain continuously insured, including the broader population of non-elderly adults with schizophrenia. Adults with schizophrenia are disproportionately publicly insured and less likely to be uninsured than the general working-age adult population5; however, little is known about whether they experience transitions among different insurance types.

To better understand insurance dynamics for insured non-elderly adults with schizophrenia, we used the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database (APCD) to examine insurance transitions for adult individuals (18–64 years) with schizophrenia who were continuously insured over a two-year period.

Methods

Data

We used the Massachusetts APCD v8.0, obtained from the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, from 2014 to 2018 for our analysis. The APCD contains health claims data and insurance eligibility details from public and many private insurance providers in Massachusetts29,30. There is full reporting by Traditional Medicaid and Medicaid managed care insurers, Marketplace plans, the Health Safety Net, and Medicare Advantage; there is partial reporting for private insurers as reporting is optional for self-insured employers. The Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis uses a proprietary algorithm to match individuals across insurance carriers over time31; we conduct additional analyses to remove records that may represent incorrect matches. Eligibility records for those covered by Traditional Medicare are not included, with the exception of those enrolled in integrated Medicare-Medicaid coverage.

Analytic sample

We identified adults with schizophrenia as those who had at least one claim with a principal or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia based on International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision (ICD-9) and ICD-10 diagnosis codes (ICD-9: 295.X excluding 295.7; ICD-10: F20.X)32,33. We limited to adults with schizophrenia who were 18 to 64 years old and a Massachusetts resident for the entire 2-year period. We further limited the sample to individuals who were continuously insured by one or more included plans during the two-year period. We made this decision as we cannot disentangle the reasons patients who transition to no longer being observed in the Massachusetts APCD; for example, individuals may become unobserved if they transition to a non-reporting private insurance plan or a Traditional Medicare plan, or they may become unobserved if they become uninsured. Individuals with data errors that could indicate issues with the unique identifier linkage process were excluded from the analysis.

Measures

Our primary outcome of interest was a binary indicator of any transition in insurance type in each person-period. We examine transitions among seven categories of insurance coverage: (1) private; (2) Traditional Medicaid; (3) Medicaid managed care; (4) plans from the health insurance marketplace; (5) Health Safety Net; (6) Medicare Advantage; and (7) integrated Medicare and Medicaid. Each period included two consecutive calendar years, which we chose to observe a multi-year period allowing for analysis of within versus across-year transitions. In our study, we had four 24-month periods (2014–2015; 2015–2016; 2016–2017; 2017–2018), which means each patient could have been included for up to four periods. An insurance transition was defined as a change in insurance type between adjacent months in the 2-year period. For example, an insurance transition could include changing from private insurance to public insurance. If multiple transitions between types were observed, we counted these even if the individual was transitioning back to the insurance type in which they were enrolled at the beginning of the period. Due to data limitations, we did not consider changes between health plans within a specific insurance type to be an insurance transition.

Massachusetts Medicaid beneficiaries generally have the choice to select either Traditional Medicaid administered by the state or a plan from a Medicaid-managed care organization. While individuals who chose the traditional state-administered program can switch into a Medicaid-managed care plan at any time, individuals who are enrolled in a Medicaid-managed care plan can generally only change during the annual plan enrollment periods34,35. Medicaid redetermination and moving between regions in the state also allows beneficiaries to switch between Medicaid plan types36.

Marketplace plans are those plans purchased from the health insurance exchange or marketplace created by the ACA. The Health Safety Net is a Massachusetts program covering specific health services at acute care hospitals or community health centers for individuals who are uninsured and underinsured; however, it does not qualify as minimum essential coverage under ACA requirements37. Individuals enrolled in the Health Safety Net were included as they had access to some care and can be observed in the data; however, in other states, these individuals are likely to be uninsured. The dataset includes Medicare Advantage, but does not include eligibility or claims information for those insured by Traditional Medicare. In October 2013, MassHealth (Medicaid) and Medicare created One Care, which is Medicare plus MassHealth for dual-eligible individuals who are between 21 to 64 years old38,39. Based on enrollment reports, 22.8% who are eligible enroll in One Care40; patients with One Care or Medicare Advantage plus secondary Medicaid would be observed in the dataset while individuals with Traditional Medicare plus secondary Medicaid outside of One Care would not be observed.

In addition, we created a binary measure for patient sex and a categorical measure for age at the start of the 2-year period. To understand the association of insurance transitions with socioeconomic status, we used patient 5-digit ZIP code to identify those living in areas in the lowest quartile of median household income41 and areas with concentrated poverty42. Concentrated poverty was defined as a ZIP code with an overall poverty rate greater than 30%43.

Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to compare any insurance transition by sample characteristics and used chi-square tests to evaluate the significance of differences between those with and without an insurance transition. Next, we estimated a multivariable logistic regression model for the binary outcome of any insurance transition with the primary independent variable being a categorical measure of insurance type at the start of the 2-year period. We included covariates of age, sex, residence in a ZIP code in the lowest quartile of median income, and residence in a ZIP code with concentrated poverty. We presented predicted probabilities of any insurance transition. Lastly, we displayed any insurance transition by insurance type using a Sankey diagram. To further display information about enrollment duration, we analyzed the timing of the initial transition for those with at least one transition, and constructed a figure showing enrollment durations in each insurance type.

We conducted three sensitivity analyses. We first repeated the main analysis with the sample but combined the Medicaid coverage into one category rather than separating into Medicaid and Medicaid managed care as in the primary analysis. Next, we repeat the analysis removing the 2014 to 2015 period to see how the results changed for dual-eligible enrollees given that One Care began in October 2013 and was still coming into effect in 2014. Lastly, we repeat the analysis using two-year periods that do not align with calendar years to determine whether our results are not sensitive to the start month of the analysis. We defined a person-period as a period of two consecutive calendar years starting on April 1 of a given year.

Standard errors were clustered at the 5-digit patient ZIP code. Standard errors for predicted probabilities are calculated using the delta method. An alpha of 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. All analysis was conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and Stata-MP 16.0 (College Station, TX). Our study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Amherst Institutional Review Board.

Results

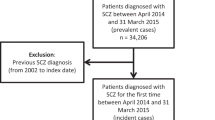

The analytic sample included 36,754 person-period observations for 19,217 unique individuals aged 18 to 64 in Massachusetts with a schizophrenia diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. 1). At the start of the study period, 39.0% were covered by Traditional Medicaid and 37.0% by Medicaid managed care (Table 1). Almost half (46.3%) of the sample resided in a ZIP code with the lowest-quartile median income, and 10.9% of patients lived in a ZIP code with concentrated poverty. Overall, more than one-sixth (15.1%) experienced at least one insurance transition over a 2-year period. Among those with any insurance transition, 70.9% experienced one insurance transition, 22.0% had two insurance transitions, and 7.1% had three or more insurance transitions. Insurance transitions were more frequent among those covered by Traditional Medicaid, Marketplace plans, and the Health Safety Net.

Figure 1 shows the regression-adjusted predicted probabilities of insurance transitions by insurance type at the start of period. In regression-adjusted results, insurance transitions were significantly less common among private insurance, Traditional Medicaid, Medicaid managed care, Health Safety Net, Medicare Advantage, and integrated Medicare and Medicaid coverage compared to individuals with Marketplace insurance (Fig. 1; full multivariate logistic regression results in Supplementary Table 1). The findings were similar in unadjusted analyses (Supplementary Fig. 2). In regression-adjusted results, individuals insured with Traditional Medicaid were 20.2 percentage points [pp] (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: −24.6 pp, −15.9 pp) less likely to have an insurance transition than those who were insured by a Marketplace plan (21.4% vs. 41.6%). In comparison, individuals insured with private insurance and Medicaid managed care plan were 32.1 pp (95% CI: −36.3 pp, −28.0 pp) and 33.5 pp (95% CI: −37.6 pp, −29.4 pp), respectively less likely to have an insurance transition compared to those who had Marketplace coverage (predicted probabilities of 9.5% private vs. 8.1% Medicaid managed care vs. 41.6% Marketplace). Insurance transitions were less common for older individuals in regression-adjusted results (Fig. 2), which was similar in unadjusted analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3). The regression-adjusted probability of a 56- to 64-year-old with schizophrenia having an insurance transition was 7.7 pp lower (95% CI: −9.1 pp, −6.4 pp) than an 18- to 25-year-old with schizophrenia.

N = 36,754 person-period observations. Adjusted results control for age, sex, residence in a ZIP code in the lowest quartile of median income, and residence in a ZIP code with concentrated poverty. Standard errors are clustered at the 5-digit ZIP code level. *Indicates a statistically significant difference in predicted probability from the reference group (Marketplace insurance) at the 5% level. 95% Confidence intervals for each group are shown with vertical bars.

N = 36,754 person-period observations. Adjusted results control for insurance type at the start of the period, sex, residence in a ZIP code in the lowest quartile of median income, and residence in a ZIP code with concentrated poverty. Standard errors are clustered at the 5-digit ZIP code level. *Indicates a statistically significant difference in predicted probability from the reference group (age 18–25 years) at the 5% level. 95% Confidence intervals for each group are shown with vertical bars.

Figure 3 displays the insurance transitions over the study period at four time points (Year 1 January, Year 1 December, Year 2 January, and Year 2 December). In the figure, it shows that insurance transitions happen not only between calendar years, but within calendar years as well. Supplementary Table 2a and b present transition matrices. The proportion of individuals who experienced an insurance transition increased over the period from 1.3% in Year 1 February to 15.1% in Year 2 December (Supplementary Fig. 4), with a modal duration of 14 months for those with at least one insurance transition (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In the sensitivity analysis combining Traditional Medicaid and Medicaid managed care, we found similar regression adjusted predicted probabilities of insurance transitions except for people insured with either Traditional Medicaid or Medicaid managed care (Fig. 4; full multivariate logistic regression results in Supplementary Table 3 and unadjusted results in Supplementary Fig. 6). In regression adjusted results, individuals insured with either Traditional Medicaid or Medicaid managed care were 36.2 pp (95% CI: −40.4 to −32.0 pp) less likely to have an insurance transition than those who were insured by a Marketplace plan (4.2% for Traditional Medicaid or Medicaid managed care vs. 40.4% Marketplace). We also display the insurance transitions over the study period for the sensitivity analysis combining Traditional Medicaid and Medicaid managed care (Supplementary Fig. 7). Similar to the main results, most insurance transitions do not happen between calendar years but occur during the calendar year.

N = 36,754 person-period observations. Adjusted results control for age, sex, residence in a ZIP code in the lowest quartile of median income, and residence in a ZIP code with concentrated poverty. Standard errors are clustered at the 5-digit ZIP code level. *Indicates a statistically significant difference in predicted probability from the reference group (Marketplace insurance) at the 5% level. 95% Confidence intervals for each group are shown with vertical bars.

In the sensitivity analysis removing the 2014 to 2015 period, the findings were consistent with the main analysis (Supplementary Table 4). In the adjusted regression results, individuals insured with integrated Medicare and Medicaid coverage were 19.6 pp (95% CI: −25.9 pp, −13.3 pp) less likely to have an insurance transition than those who were insured by a Marketplace plan.

In the sensitivity analysis changing the period to an April start, the findings were consistent with the main analysis (Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, 15.8% experienced at least one insurance transition over a 2-year period, and regression adjusted results were similar.

Discussion

Overall, we found one in six continuously insured people with schizophrenia had at least one insurance transition among insurance types during a two-year period. Our results indicate that insurance transitions were particularly common for individuals with Marketplace plans, those covered by the Traditional Medicaid program, and those in the Health Safety Net. Among those with at least one insurance transition, we found approximately 30% had more than one insurance transition over a 2-year period.

Our findings align with other studies examining individuals with serious mental illness experiencing frequent insurance disruptions, including either moving between insurance types or experiencing coverage gaps22,23,24. We found that insurance transitions between insurance types among non-elderly continuously insured adults with schizophrenia are frequent, although less common than in the most closely related study, which was done in a more limited sample. In that study, Pesa and colleagues found 54 and 85% of young adults with a newly observed schizophrenia diagnosis experienced a change in insurance type after 12 months and 48 months, respectively26. Given their focus on young adults with private insurance at start of period – something that is relatively uncommon among those with schizophrenia5, they found the most common insurance transition was from private insurance plan to a Medicaid plan26, which might be impacted by the ACA provision of dependent coverage ending at age 26 or new qualification for public insurance programs after a schizophrenia diagnosis. We similarly found that younger individuals were more likely to experience an insurance transition compared to oldest age category (56–64) with schizophrenia.

Next, insurance transitions were particularly common among those covered by the Traditional Medicaid program while people with a Medicaid managed care plan had more stable coverage. Our findings are consistent with the literature indicating that people covered by Medicaid plans are particularly vulnerable to insurance disruptions – either a change in insurance type or a coverage gap – including people who are dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare44,45,46,47,48. The literature has also shown that Traditional Medicaid is more vulnerable to insurance disruptions compared to Medicaid-managed care45. Medicaid insurance disruptions – primarily coverage gaps – are associated with increased care utilization, including inpatient hospitalization and outpatient services14,15,16,17,18. Our findings show that after the ACA, continuously insured individuals with schizophrenia covered by Medicaid experience high rates of insurance transitions; thus, examining Medicaid eligibility and redetermination policies might be beneficial to understand why these transitions occur49. For instance, automatic re-enrollment policies have been seen as beneficial tools in preventing insurance disruptions50; although primarily designed to avoid coverage gaps, these automatic re-enrollment policies may have a role in reducing insurance transitions as well.

Besides insurance transitions being common among those with Traditional Medicaid, transitions were also frequent for individuals with a Marketplace plan. This finding is consistent with prior research showing Marketplace plans have high rates of disruptions9,51, which can occur after relatively small changes in income or changes in family status. Increasing the stability of Marketplace coverage may be a policy priority given high-risk populations insured by this coverage.

Overall, individuals with schizophrenia require consistent treatment to address symptoms and decrease untreated psychosis52. Increased provider continuity for mental health care has been associated with lower costs for Medicaid plans53. Health insurance transitions, even without gaps in coverage, may result in negative impacts in care utilization and outcomes9,10,11,12,13. In addition, insurance type may impact the type and amount of care received and whether continuity of care can be maintained with their clinicians54,55. Given provider networks differ across plans and insurance type8,9,56,57, continuity of care, especially for more specialized care, might be difficult for those who experience an insurance transition despite being continuously insured.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our study was limited to Massachusetts and thus may not be representative of the population with schizophrenia nationally. However, although Massachusetts has the lowest uninsurance rate in the US7, uninsurance rates among those with schizophrenia nationally are very low after the ACA5. Given the limitation of our findings to Massachusetts, there may be different types of insurance transitions in other states based on the setup and eligibility requirements of their state Medicaid program and programs for dual eligible, higher rates of Medicaid disruptions, and/or have a smaller proportion of the population with schizophrenia who is continuously insured. Second, our data do not allow us to discern reasons for insurance transitions, so identifying policy responses to ensure more coverage stability is difficult. However, attention by state Medicaid programs to minimizing disruptions among different Medicaid types may be a key priority to maintain continuity. Third, some individuals have multiple eligibility records for the same month in the Massachusetts APCD. We have used a prioritization algorithm to ensure that we maintain continuity of insurance type, when possible, but multiple eligibility records may be an indicator of not disenrolling from a plan from which one is no longer actively receiving benefits. For example, an individual could still be enrolled in Medicaid but potentially move, die, or be incarcerated. One study found that only 3% of individuals with serious mental illness who were incarcerated were disenrolled from their Medicaid plan58. Thus, this Medicaid eligibility record might persist for some time – other insurance types may be quicker to remove eligibility, and thus we may overestimate transitions back into Medicaid coverage. Fourth, our study does not examine changes between plans within an insurance type. While an individual could have the same insurance type throughout the period, they could have experienced insurance transition by switching health plans. Switching health plans within an insurance type could also impact access to care and continuity of care due to differences in provider network and benefits59, and thus our estimates are a conservative measure of insurance transitions. Fifth, due to Gobeille v Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., the APCD does not contain full reporting by self-insured employers60; additionally, due to access restrictions, it does not include those with Traditional Medicare. As a result, we do not observe individuals with continuous insurance from non-reporting insurance plans, which may result in overstating or understating the insurance transitions for people with schizophrenia. However, given most individuals with schizophrenia are enrolled in public insurance, the lack of private non-reporting insurance plans is less of a concern; among those otherwise eligible who begin the two-year period in private insurance, 7% of those dropped from the dataset altogether over the period (author’s analysis).

Conclusions

Continuously insured adults with schizophrenia encounter frequent insurance transitions over a two-year period, which may leave them vulnerable to barriers in accessing care and high-quality care. These transitions were particularly common among those covered by the Traditional Medicaid program and by Marketplace plans, suggesting that attention to maintaining stable insurance within the Traditional Medicaid program and the Marketplace may be important to improve care for this population. The insurance transitions may lead to decreased care continuity and access to care for this population. Further research is needed to identify the impacts of insurance transitions on care utilization among individuals with schizophrenia.

Data availability

The Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database is available for purchase to qualified researchers from the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis.

Code availability

The codes used for this study can be accessed upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Puntis, S., Rugkåsa, J., Forrest, A., Mitchell, A. & Burns, T. Associations between continuity of care and patient outcomes in mental health care: a systematic review. Psychiatr. Serv. 66, 354–363 (2015).

National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia

Villarroel, M. A. & Cohen, R. A. Health Insurance Continuity and Health Care Access and Utilization, 2014. NCHS Data Brief 249, 1–8 (2016).

Khaykin, E., Eaton, W. W., Ford, D. E., Anthony, C. B. & Daumit, G. L. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 61, 830–834 (2010).

Geissler, K. H., Ericson, K. M., Simon, G. E., Qian, J. & Zeber, J. E. Differences in Insurance Coverage for Individuals With Schizophrenia After Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 278–279 (2023).

Wu, E. Q., Shi, L., Birnbaum, H., Hudson, T. & Kessler, R. Annual prevalence of diagnosed schizophrenia in the USA: a claims data analysis approach. Psychol. Med. 36, 1535–1540 (2006).

Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly 0-64, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-0-64/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Orfield, C., Hula, L., Barna, M. & Hoag, S. The Affordable Care Act and Access to Care for People Changing Coverage Sources. Am. J. Public Health 105, S651–S657 (2015).

Sommers, B. D., Gourevitch, R., Maylone, B., Blendon, R. J. & Epstein, A. M. Insurance Churning Rates For Low-Income Adults Under Health Reform: Lower Than Expected But Still Harmful For Many. Health Aff. (Millwood) 35, 1816–1824 (2016).

Brugnoli-Ensin, I. & Mulligan, J. Instability in Insurance Coverage: The Impacts of Churn in Rhode Island, 2014-2017. R I Med J (2013) 101, 46–49 (2018).

Lavarreda, S. A., Gatchell, M., Ponce, N., Brown, E. R. & Chia, Y. J. Switching health insurance and its effects on access to physician services. Med. Care 46, 1055–1063 (2008).

Banerjee, R., Ziegenfuss, J. Y. & Shah, N. D. Impact of discontinuity in health insurance on resource utilization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 10, 195 (2010).

Barnett, M. L. et al. Insurance Transitions and Changes in Physician and Emergency Department Utilization: An Observational Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 32, 1146–1155 (2017).

Pilon, D. et al. Are Medicaid Coverage Gaps Associated with Higher Health Care Resource Utilization and Costs in Patients with Schizophrenia? Popul Health Manag 23, 234–242 (2020).

Harman, J. S., Hall, A. G. & Zhang, J. Changes in health care use and costs after a break in Medicaid coverage among persons with depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 58, 49–54 (2007).

Harman, J. S., Manning, W. G., Lurie, N. & Christianson, J. B. Association between interruptions in medicaid coverage and use of inpatient psychiatric services. Psychiatr. Serv. 54, 999–1005 (2003).

Ji, X., Wilk, A. S., Druss, B. G. & Cummings, J. R. Effect of Medicaid Disenrollment on Health Care Utilization Among Adults With Mental Health Disorders. Med. Care 57, 574–583 (2019).

Ji, X., Wilk, A. S., Druss, B. G., Lally, C. & Cummings, J. R. Discontinuity of Medicaid Coverage: Impact on Cost and Utilization Among Adult Medicaid Beneficiaries With Major Depression. Med. Care 55, 735–743 (2017).

Burns, M. E., Huskamp, H. A., Smith, J. C., Madden, J. M. & Soumerai, S. B. The Effects of the Transition From Medicaid to Medicare on Health Care Use for Adults With Mental Illness. Med. Care 54, 868–877 (2016).

Dong, J., Zaslavsky, A. M., Ayanian, J. Z. & Landon, B. E. Turnover among new Medicare Advantage enrollees may be greater than perceived. Am. J. Manag. Care 28, 539–542 (2022).

Fang, H., Frean, M., Sylwestrzak, G. & Ukert, B. Trends in Disenrollment and Reenrollment Within US Commercial Health Insurance Plans, 2006-2018. JAMA Network Open 5, e220320–e220320 (2022).

Rabinowitz, J., Bromet, E. J., Lavelle, J., Hornak, K. J. & Rosen, B. Changes in insurance coverage and extent of care during the two years after first hospitalization for a psychotic disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 52, 87–91 (2001).

Golberstein, E., Busch, S. H., Sint, K. & Rosenheck, R. A. Insurance Status and Continuity for Young Adults With First-Episode Psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 72, 1160–1167 (2021).

Dodds, T. J. et al. Who is paying the price? Loss of health insurance coverage early in psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 62, 878–881 (2011).

Wilson, A. B. et al. Patterns in Medicaid Coverage and Service Utilization Among People with Serious Mental Illnesses. Community Ment. Health J. 58, 729–739 (2022).

Pesa, J. et al. Real-world analysis of insurance churn among young adults with schizophrenia using the Colorado All-Payer Claims Database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 28, 26–38 (2022).

Fung, V., Yang, Z., Cook, B. L., Hsu, J. & Newhouse, J. P. Changes in Insurance Coverage Continuity After Affordable Care Act Expansion of Medicaid Eligibility for Young Adults With Low Income in Massachusetts. JAMA Health Forum 3, e221996–e221996 (2022).

Goldman, A. L. & Sommers, B. D. Among Low-Income Adults Enrolled In Medicaid, Churning Decreased After The Affordable Care Act. Health Aff. (Millwood) 39, 85–93 (2020).

Center for Health Information and Analysis. Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database, https://www.chiamass.gov/ma-apcd/

Center for Health Information and Analysis. Overview of the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database. Report No. 16-258-CHIA, (Boston, MA, 2016).

Center for Health Information and Analysis. CHIA’s New MA APCD Master Patient Index, https://www.chiamass.gov/assets/docs/p/apcd/MA-APCD-CY2021/MA-APCD-CY2021-Overview-of-New-MA-APCD-Master-Patient-Index.pdf (December 2022).

Stewart, C. C. et al. Impact of ICD-10-CM Transition on Mental Health Diagnoses Recording. EGEMS (Wash DC) 7, 14 (2019).

Simon, G. E. et al. First Presentation With Psychotic Symptoms in a Population-Based Sample. Psychiatr. Serv. 68, 456–461 (2017).

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Plan Selection Period, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/plan-selection-period

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Primary Care Clinician (PCC) Plan for MassHealth Members, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/primary-care-clinician-pcc-plan-for-masshealth-members

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Fixed Enrollment Period, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/fixed-enrollment-period

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Health Safety Net for Patients, https://www.mass.gov/service-details/health-safety-net-for-patients

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. One Care Administrative Information, https://www.mass.gov/one-care-administrative-information

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. One Care, https://www.mass.gov/one-care

Commonwealth of Massachusetts & Executive Office of Health & Human Services. One Care: December 2019 Enrollment Report, https://www.mass.gov/doc/december-2019-enrollment-report-0/download

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table S1901, https://data.census.gov/table?q=S1901&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S1901

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table S1701, https://data.census.gov/table?q=S1701&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S1701

Meade, E. E. Researchers most often define concentrated poverty as a significantly high proportion of areas residents living below the poverty level., https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/overview-community-characteristics-areas-concentrated-poverty (2014).

Ku, L. The Stability and Continuity of Medicaid Coverage. Ann. Intern. Med. 176, 127–128 (2023).

Sommers, B. D. Loss of health insurance among non-elderly adults in Medicaid. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 24, 1–7 (2009).

Riley, G. F., Zhao, L. & Tilahun, N. Understanding factors associated with loss of medicaid coverage among dual eligibles can help identify vulnerable enrollees. Health Aff. (Millwood) 33, 147–152 (2014).

Ndumele, C. D., Lollo, A., Krumholz, H. M., Schlesinger, M. & Wallace, J. Long-Term Stability of Coverage Among Michigan Medicaid Beneficiaries: A Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 176, 22–28 (2023).

Frenier, C. & McIntyre, A. Insurance Coverage Transitions After Disenrollment From Medicaid in Minnesota. JAMA Network Open 6, e239379–e239379 (2023).

Capoccia, V., Croze, C., Cohen, M. & O’Brien, J. P. Sustaining enrollment in health insurance for vulnerable populations: lessons from Massachusetts. Psychiatr. Serv. 64, 360–365 (2013).

McIntyre, A. & Shepard, M. Automatic Insurance Policies - Important Tools for Preventing Coverage Loss. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 408–411 (2022).

Jeung, C., Attanasio, L. B. & Geissler, K. H. Transitions in Health Insurance During the Perinatal Period Among Patients With Continuous Insurance Coverage. JAMA Network Open 5, e2239803–e2239803 (2022).

Mojtabai, R. et al. Unmet need for mental health care in schizophrenia: an overview of literature and new data from a first-admission study. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 679–695 (2009).

Chien, C. F., Steinwachs, D. M., Lehman, A., Fahey, M. & Skinner, E. A. Provider Continuity and Outcomes of Care for Persons with Schizophrenia. Mental Health Services Research 2, 201–211 (2000).

Busch, S. H., Ndumele, C. D., Loveridge, C. F. & Kyanko, K. A. Patient Characteristics and Treatment Patterns Among Psychiatrists Who Do Not Accept Private Insurance. Psychiatr. Serv. 70, 35–39 (2019).

Rabinowitz, J. et al. Relationship between type of insurance and care during the early course of psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 1392–1397 (1998).

Zhu, J. M., Meiselbach, M. K., Drake, C. & Polsky, D. Psychiatrist Networks In Medicare Advantage Plans Are Substantially Narrower Than In Medicaid And ACA Markets. Health Aff. (Millwood) 42, 909–918 (2023).

Cooper, M. I., Attanasio, L. B. & Geissler, K. H. Maternity care clinician inclusion in Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations. PLoS One 18, e0282679 (2023).

Morrissey, J. P. et al. Assessing gaps between policy and practice in Medicaid disenrollment of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 57, 803–808 (2006).

Ericson, K. M. & Starc, A. Measuring Consumer Valuation of Limited Provider Networks. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 115–119 (2015).

Fuse Brown, E. C. & King, J. S. The Consequences Of Gobeille v. Liberty Mutual For Health Care Cost Control. Health Affairs Forefront. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/consequences-em-gobeille-em-span-class-lowercase-v-span-em-liberty-mutual-em-health. (March 10, 2016).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34MH123628. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BLR conducted the formal analysis, interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. CJ contributed to data acquisition and analysis, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. JEZ, GES, KME, and JQ contributed to study design, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. KHG conceptualized and designed the study, interpretation of data, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranchoff, B.L., Jeung, C., Zeber, J.E. et al. Transitions in health insurance among continuously insured patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr 10, 25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00446-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00446-4