Abstract

The archetypical 3D topological insulators Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3, and Sb2Te3 commonly exhibit high bulk conductivities, hindering the characterization of the surface state charge transport. The optimally doped topological insulators Bi2Te2Se and Bi2−xSbxTe2S, however, allow for such characterizations to be made. Here we report an experimental comparison of the conductance for the topological surface and bulk states in Bi2Te2Se and Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S, based on temperature-dependent high-pressure measurements. We find that the surface state conductance at low temperature remains constant in the face of orders of magnitude increase in the bulk state conductance, revealing in a straightforward way that the topological surface states and bulk states are decoupled at low temperatures, consistent with theoretical models, and confirming topological insulators to be an excellent venue for studying charge transport in 2D Dirac electron systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological insulators (TIs) are, theoretically, quantum materials that display a bulk band gap like an ordinary insulator, but a conducting surface state that is topologically protected due to a combination of spin-orbit interactions and time-reversal symmetry.1,2,3,4,5,6 The topologically non-trivial nature of the spin-helical Dirac fermion surface states in TIs has attracted wide interest in the research community because it results in rich new physics and materials that have potential applications in quantum technology.7,8

An ideal TI should have topologically-protected metallic surface states (TSS), but also an electrically insulating bulk. Unfortunately, early generations of bulk TIs, such as the M2X3 (M = Bi and Sb, X = S, Se, and Te) tetradymites, are not typically insulating,2,9,10,11,12,13 which prevented the early characterizations of many of the charge transport properties of the surface states. Recently, however, insulating bulk crystals of the tetradymite TI variants Bi2Te2Se (BTS)14,15,16 and Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S (BSTS)17,18 have been grown. These two materials are high-quality TIs with very low bulk carrier concentrations.16,18,19,20 The bulk bandgaps of BTS and BSTS are ~310 meV14,19,20,21 and ~350 meV18 respectively, and especially the Dirac crossing in the TSS band of BSTS is well isolated from the bulk states. These compounds provide an ideal platform for studying the evolution of the TSS conductance and its connections with the conductance of the bulk states.

Although it is widely accepted that topological surface states (TTS) and bulk electronic states should act independently, the degree to which they might or might not intermix has not been addressed in a straightforward experiment. We address that shortcoming here, finding that the surface state and bulk charge transport in the two TIs are truly independent at low temperatures. We use transport measurements under applied pressure to show this, because pressure is a clean way to tune electronic states in materials without introducing chemical complexity.22 High-pressure measurements addressing other issues have been employed in studies on some TIs,23,24,25,26,27,28 but here we report the high-pressure investigations of insulating BTS and BSTS single crystals that directly address the interdependence of the surface state and bulk state conductances. The surprising result is that, above temperatures of ~10 K (here we defined this temperature as the low temperature), the conductance of the bulk and surface states appears to be intermixing and the bulk conductance increases by orders of magnitude from the low temperature to high temperature, while, below 10 K, the surface state conductance changes little with temperature or pressure and dominates the transport property, an indication that they are truly independent at that temperature and below.

Theorists have pointed out since the earliest days that the surface states on TIs are protected by time reversal and spatial inversion symmetry.1,6 The analysis of quantum oscillations and other characteristics of the electronic states at low temperatures have been consistent with this expectation, but the current measurements show the conditions under which this can be assumed to be true in high-quality materials. Logically speaking, TIs require materials with relatively small bulk electronic band gaps due to the importance of band inversion and the impact of spin-orbit coupling on the bulk electronic band structure at certain points in the Brillouin zone. Thus at high temperatures electrical transport measurements on all but the thinnest crystals should be dominated by the bulk states, in which charge carriers are present due to thermal excitation. Conversely, the metallic surface states dominate at low temperatures where they short circuit the high resistance of the bulk states in a sample crystal. In intermediate temperature regimes, a combined conductance contributed from the bulk and surface states is expected. In this study, we performed high-pressure resistance and X-ray diffraction measurements on high-quality BTS and BSTS samples, optimally doped insulating TIs. The current measurements allow us to define these issues experimentally. We find that the conductance of the of these two TIs remains constant below crossover pressure and presents the independence of the bulk state charge transport.

Results and discussions

Firstly it is important to establish that no structural phase transitions are present in the pressure range of our experiments that would complicate the interpretation of the data. It is known that BTS maintains its tetradymite structure to 8 GPa,26 but there are no reports of the high-pressure structure of BSTS. Thus, we performed high-pressure X-ray diffraction measurements to characterize the structure of BSTS; no structural phase transition was found up to beyond the pressures of the current measurements (see SI figure S1).

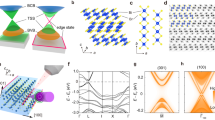

We performed temperature-dependent resistance measurements on the single crystals of BTS and BSTS at low pressures. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, the resistance of the two materials increases strongly upon cooling and then saturates at ~88 K for BTS and ~155 K for BSTS. The saturation of the resistance occurs below temperatures where the metallic topological surface state resistance “short circuits” the strongly increasing bulk resistance, even for bulk crystal pieces.10,16,29,30 We denote the resistance saturation temperature as T* (Fig. 1a, b). T* for both TIs shifts to lower temperature upon increasing pressure (Fig. 1c and Fig. S2); this is because the bulk insulating behavior of the two materials is systematically suppressed by applying pressure, through a decrease in the activation energy (Ea). Because both BTS and BSTS have the characteristic of an intrinsic semiconductor,18,19,20 we estimated the Eα by the Arrhenius equation (SI, Fig. S2) and found that Eα for both TIs decreases with increasing pressure (Fig. 1d and S2). Thus the decrease in the crossover temperature T* with pressure is associated with a pressure-induced reduction in the activation energy for the generation of bulk carriers. As the resistance of the bulk goes down with pressure, one has to cool to lower temperatures to get comparable bulk and surface state conductances. We note that T* for BSTS is higher than that of BTS (Fig. 1c), a difference that results from the relative magnitudes of the transport activation energies. Indeed, the bandgap of bulk BSTS is larger than that of bulk BTS (SI, Fig. S2). In addition, Ea for BSTS decreases less strongly under pressure than is seen for BTS, resulting in the fact that T* for BSTS shows a weaker dependence on pressure than is seen for BTS (Fig. 1c, d and S2).

Transport properties of the 3D topological insulators BTS and BSTS as functions of temperature and pressure. a, b Temperature dependence of the electrical resistance obtained at different pressures for BTS and BSTS, displaying the evolution of T*, the temperature that marks the crossover between TSS-dominated and bulk-dominated resistivity. c Pressure dependence of the relative behaviors of the crossover temperature, T*(P)/T*(0.1 GPa), for the two TIs BTS and BSTS, showing a downward trend with increasing pressure. The data labeled by colored circles were obtained from different experimental runs. d The relative transport activation energies (Ea) as a function of pressure for BTS and BSTS, displaying a strong decrease with pressure. The T* and Ea values at the lowest pressures are ~125 K and ~144 meV for BTS and ~180 K and ~165 meV for BSTS respectively. Further information can be found in the SI, Fig. S2

To illustrate the effect of pressure on the conductances of the TSS in BTS and BSTS more quantitatively, we describe the resistance-temperature (R-T) behavior of these materials via the commonly-employed two-channel model.17,31,32 Because conductivities are additive, the total conductance (Gtot) is then the sum of a thermally activated bulk conductance (Gbul) and a metallic surface conductance (Gsur)31,32:

In this way we can examine Gsur(T) by subtracting Gbul (T) from our experimental data, where the semiconducting Gbul(T) is simply extrapolated to temperatures lower than our fit temperatures. Because BTS still has a small impurity band between the valance and conductance bands,16,33 we apply variable range hopping (VRH) process instead of Arrhenius law to obtain a better fit for the plot of resistance versus temperature. The same method was also applied for the data fit on the BSTS sample. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the black squares are our experimental data obtained at low pressure, the red solid lines are the data fitted by Rbul (T) = [R0bul exp[(T/T0)−0.25]. It is seen that this equation can give a significant overlap in the activated temperature range10,16(SI, Fig. S3), where Gbul (T) = 1/Rbul(T) and the green triangles are the data after subtraction. The green triangles therefore represent the temperature-dependent conductance of the surface states only. Rbul increases exponentially over a wide range of decreasing temperature. Based on these results, we can define two relevant temperatures as T* and T′. Below T*, the surface state dominates the resistance, while above T′, the bulk insulating state dominates. Between T* and T′, both surface and bulk carriers contribute in a major way to the total conductance of the samples. Because the two-channel model can describe our experimental data well (Fig. 2a, b), it allows us to extract the pressure and temperature-dependent conductivities of both the surface and bulk states for the two materials investigated (Fig. 2c, d, the details see Fig. S4), in which the equations of Gbul (T) = 1/[R0bul exp[(T/T0)−0.25] and Gsur (T) = 1/[R0 + AT] are employed. It is seen that the Gbul for both TIs increases dramatically above 100 K, especially under pressure, while in contrast Gsur appears to be insensitive to both temperature and pressure. Specifying this general behavior in further detail, the temperature–pressure regime where the surface states and the bulk states dominate the sample resistances, for samples where the ratio of the surface area to the sample thickness is approximately 4680 µm2:12 µm (78 × 60:12 = 390:1), are shown in the SI (Fig S5). Note that conductance G goes as G = (e2/h)kFl, where e is the charge, h is the Plank constant, kF is the wave vector of Fermi surface and l is the mean free path. Because e and h are constants, and the Gsur values of the BTS and BSTS samples are similar (Fig. 3a), it can be known that the kFl product of these two materials should have the similar value. For the TTS of other tetradymite TIs, whether they have a similar kFl value deserves further investigation.

The temperature and pressure-dependent resistances and conductances for BTS and BSTS. a, b Resistance as a function of temperature at fixed pressure for the two materials. The back squares are our experimental data, the red circles are the data fitted for the insulating bulk in the high temperature range by the equation of Rbul (T) = [R0bul exp[(T/T0)−0.25] and the green triangles are the surface state conductance, obtained from our experimental (black) data by subtracting the fitted bulk conductance extrapolated from the high temperature range (red). c, d The pressure and temperature dependence of the conductance of the TSS and the insulating bulk for BTS and BSTS, showing that the conductance of the bulk (Gbul) increases with both increasing pressure and temperature, while the conductance of TSS (Gsur) stays relatively constant with pressure and temperature

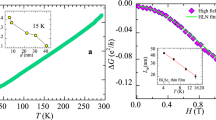

Summary of the temperature and pressure-dependent conductances for both BTS and BSTS. a Shows that the high temperature conductance converted from the measured resistance data, dominated by the bulk states, increases by more than an order of magnitude under pressure for both materials, while at low temperatures, (i.e., 10 K), where the surface state conductance dominates, the conductances are relatively independent of pressure. b Illustrates the relative changes in pressure-dependent conductances in specific, plotted as the ratio of the conductance change at pressure to the conductance at 1 GPa (ΔG = G(P)−G(1 GPa)), for both TIs, at both high and low temperatures. c A schematic of the electronic structures for optimally doped BTS and BSTS in the vicinity of the gamma point in the Brillouin Zone under pressure. (Note that this schematic is faithful to the electronic system for BSTS but that the Dirac crossing for BTS is within the notch in the valence band dispersion for that material, not relevant for the considerations here.)

Figures 3 and 4 show a summary of the data that exhibit the independence of the bulk and surface state conductances at low temperatures and pressures. Figure 3 shows the details of the pressure-dependent and temperature-dependent behavior of the conductances for both the bulk and surface states, along with a schematic of the electronic structure of the materials as a guide for interpreting the data. Figure 3a shows the pressure dependence of the high temperature, bulk-dominated behavior, and the low temperature, surface dominated behavior, for both BTS and BSTS. It is found that the conductances obtained at 270 K show a linear increase upon increasing pressure in the logarithmic scales, reflecting a thermal excitation behavior from the bulk. However, the conductances obtained at 10 K remain almost constant at low pressure. The relative insensitivity of the low temperature conductance to pressure is immediately apparent for both TIs, but this is illustrated more explicitly in Fig. 3b, where the same data are plotted as relative change in conductance. Figure 3b shows that there is very little change in the total sample conductance in BTS and BSTS at low pressures and low temperatures, because this is where the surface state conductance dominates.

The independence of surface state conductance and bulk conductance at low temperatures in topological insulators, which are converted from measured resistance data. a Pressure dependence of the surface state conductances in BTS and BSTS at 10 K. P* represents the crossover pressure. b The surface state conductance at 10 K plotted vs. the bulk state conductance at 270 K for both BTS and BSTS. Note the linear-log scales for figure (b). These representations show that in the low temperature and low pressure regime, where the bulk conductances are smallest, the surface state conductance is independent of both the bulk state conductance

It is noteworthy that, at ambient or low pressure, the total conductance below T′ is the sum of the two contributions from the bulk and the surface. The bulk property varies with decreasing temperature, and especially it can be tuned by pressure, whereas the surface states transport properties are found to be almost temperature-independent and pressure-independent. The contribution of the bulk carriers, which jump from the gaped valence band through the thermal excitation, to the total conductance becomes more and more pronounced with the increase of pressure due to the pressure-induced reduction in activation energy gap (Fig. 3c). At a crossover pressure (P*), P* = 3.0 GPa for BTS and P* = 4.3 GPa for BSTS, the effect of the bulk carrier on the transport property is enhanced. Above the crossover pressure, the conductance of the surface state exhibits an increase with pressure (Fig. 3a, b). The possible reason for the different crossover pressures for these two TIs is that BTS has a smaller bulk gap than optimally doped BSTS, therefore for BSTS less charge carriers can be excited into the conducting band, as a result that its surface state conductance is less sensitive to both pressure and temperature.

The essential character of the surface state conductance relative to applied pressure and the bulk state conductance are shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4a shows the pressure dependence of the surface state conductances in BTS and BSTS at 10 K, on linear scales. As seen in the other data analysis presented, again, the surface state conductance in BTS is more sensitive to temperature and pressure than in BSTS. This is not an intrinsic feature of the surface state but rather reflects the more dramatic changes in the bulk transport gap Ea with pressure in BTS than for BSTS. The fact that the pressure-dependent behavior of the surface state conductance in BTS at around 10 K is not intrinsic to the surface state is illustrated nicely by the convergence of the surface state conductance to a similar value at low temperatures and pressures. The same behavior is more pronounced for BSTS. Figure 4b shows a full summary of the results of this study. In this figure, the surface state conductance at 10 K is plotted vs. the bulk state conductance at 270 K for both materials on a log-linear plot. The bulk state conductance at 270 K, taken by direct measurement, is taken as a model-independent reflection of the bulk conductance, although the same is clearly illustrated when using the bulk conductances extrapolated to 10 K (i.e., Fig. S6). Our results indicate that BTS and BSTS share the same feature that the TTS are independent of the bulk conductance.

In summary, our experiments reveal the independence of the bulk and TTS charge transport in optimally doped tetradymite TIs at low temperature and low pressure. This is one of the fundamental characteristics predicted and assumed to be the case in TIs. We have done this by studying the effect of pressure on the TTS and bulk state conductances in the insulating 3D TIs BTS and BSTS. These two TIs show the same behavior under pressure: the crossover temperatures T* of the TTS-dominated conductance shifts to lower temperature with increasing pressure due to the pressure-induced metallization of the normally insulating bulk. The experiments show that the conductance of the TTS remains constant at pressure below P*, in spite of the fact that the conductance of the bulk states increases by several orders of magnitude. The weak metallic temperature-dependent behavior of the TSS demonstrates a remarkably robust independence of the two conductance channels. Thus measurements of surface state quantization, such as quantum oscillations, typically performed at temperatures considerably lower than 10 K, can be considered as good probes of the surface state transport when performed on bulk insulating crystals of materials such as BTS and BSTS. The unaffected conductance of the TTS in BTS and BSTS suggests that these materials may have potential applications in quantum computation, as proposed for intrinsic TIs.

Methods

High-quality single crystals of BTS and BSTS were grown by the vertical Bridgman method, as described in ref. 18 Before the experiments, the crystals were freshly cleaved to expose pristine basal plane (001) surfaces.

High-pressure resistance measurements for the two TIs were performed in a Toroid type high-pressure cell.34 A mixture of glycerin and water, a liquid pressure-transmitting medium, was used for these measurements. The pressure was determined by monitoring the shifts of the superconducting transition temperature of pure lead.35

High-pressure X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed in a diamond anvil cell at room temperature on beamline 4W2 at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility and on beamline 15U at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Diamonds with low birefringence were selected for these XRD measurements. A monochromatic X-ray beam with a wavelength of 0.6199 Å was employed and silicon oil was taken as a pressure-transmitting medium. The pressure for all measurements in the diamond anvil cell was determined by the ruby fluorescence method.36

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Xia, Y. et al. Observation of a large-gap topological-insulator class with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys. 5, 398–402 (2009).

Bernevig, B. A., Hughes, T. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Quantum spin Hall effect and topological phase transition in HgTe quantum wells. Science 314, 1757–1761 (2006).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

König, M. et al. Quantum spin Hall insulator state in HgTe quantum wells. Science 318, 766–770 (2007).

Fu, L., Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106803 (2007).

Wilczek, F. Majorana returns. Nat. Phys. 5, 614–618 (2009).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Checkelsky, J. G. et al. Quantum interference in macroscopic crystals of nonmetallic Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 246601 (2009).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Optimizing Bi2−xSbxTe3−ySey solid solutions to approach the intrinsic topological insulator regime. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165311 (2011).

Jia, S. et al. Defects and high bulk resistivities in the Bi-rich tetradymite topological insulator Bi2+xTe2−xSe. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165119 (2012).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional topological insulator, Bi2Te3. Science 325, 178–181 (2009).

Heremans, J. P., Cava, R. J. & Samarth, N. Tetradymites as thermoelectrics and topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17049–1 (2017).

Mi, J.-L. et al. Phase separation and bulk p-n transition in single crystals of Bi2Te2Se topological insulator. Adv. Mater. 25, 889–893 (2013).

Ando, Y. Topological insulator materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 102001 (2013).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Large bulk resistivity and surface quantum oscillations in the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 82, 241306 (2010).

Misawa, T. et al. Preparation and characterization of Sn-BSTS topological insulator for universality test of the quantum Hall effect. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 66, 1489–1495 (2017).

Kushwaha, S. K. et al. Sn-doped Bi1.1Sb0.9Te2S bulk crystal topological insulator with excellent properties. Nat. Commun. 7, 11456 (2016).

Arakane, T. et al. Tunable Dirac cone in the topological insulator Bi2-xSbxTe3-ySey. Nat. Commun. 3, 636 (2012).

Miyamoto, K. et al. Topological surface states with persistent high spin polarization across the Dirac point in Bi2Te2Se and Bi2Se2Te. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166802 (2012).

Akrap, A. et al. Optical properties of Bi2Te2Se at ambient and high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 86, 235207 (2012).

Nayak, A. P. et al. Pressure-modulated conductivity, carrier density, and mobility of multilayered tungsten disulfide. ACS Nano 9, 9117–9123 (2015).

Xi, X. et al. Signatures of a pressure-induced topological quantum phase transition in BiTeI. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 155701 (2013).

Kirshenbaum, K. et al. Pressure-induced unconventional superconducting phase in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 087001 (2013).

Stillwell, R. L., Jenei, Z., Weir, S. T., Vohra, Y. K. & Jeffries, J. R. Superconducting Bi2Te: pressure-induced universality in the (Bi2)m(Bi2Te3)n series. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094511 (2016).

Zhao, J. et al. Structural phase transitions of (Bi1−xSbx)2(Te1−ySey)3 compounds under high pressure and the influence of the atomic radius on the compression processes of tetradymites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 2207–2216 (2017).

Matsubayashi, K., Terai, T., Zhou, J. S. & Uwatoko, Y. Superconductivity in the topological insulator Bi2Te3 under hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125126 (2014).

Nikitin, A. M., Pan, Y., Huang, Y. K., Naka, T. & de Visser, A. High-pressure study of the basal-plane anisotropy of the upper critical field of the topological superconductor SrxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 94, 144516 (2016).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Fermi level tuning and a large activation gap achieved in the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se by Sn doping. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155301 (2012).

Taskin, A. A., Ren, Z., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Observation of Dirac holes and electrons in a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 016801 (2011).

Xu, Y. et al. Observation of topological surface state quantum Hall effect in an intrinsic three-dimensional topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 10, 956–963 (2014).

Gao, B. F. et al. Gate-controlled linear magnetoresistance in thin Bi2Se3 sheets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 212402 (2012).

Kushwaha, S. K. et al. Comparison of Sn-doped and nonstoichiometric vertical-Bridgman-grown crystals of the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 143708 (2014).

Petrova, A. E., Sidorov, V. A. & Stishov, S. M. High-pressure helium gas apparatus and hydrostatic toroid cell for low-temperatures applications. Phys. B 359-361, 1463–1465 (2005).

Eiling, A. & Schilling, J. S. Pressure and temperature dependence of electrical resistivity of Pb and Sn from 1–300 K and 0–10 GPa-use as continuous resistive pressure monitor accurate over wide temperature range; superconductivity under pressure in Pb, Sn, and In. J. Phys. F: Metal. Phys. 11, 623–639 (1981).

Mao, H. K., Xu, J. & Bell, P. M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank Profs. Hongming Weng, Qianghua Wang, N. Phuan Ong, Yi Zhou, and Dr. Chongchong Le for helpful discussions. R.J.C. would like to thank Gene Mele for a conversation several years ago about the expected behavior of the bulk band gap in topological insulators under pressure, initially motivating this experiment. The work in China was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFA0302900, 2016YFA0300300 and 2017YFA0303103), the NSF of China (Grants No. 11427805, No. U1532267, No. 11604376), the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB25000000). The work at Princeton was supported by the ARO MURI on Topological Insulators, grant W911NF-12-1-0461.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and R.J.C. designed the high-pressure research. S.C., V.A.S. J.G., Y.Z., and L.S. performed the high pressure resistance measurements. S.K.K and R.J.C. grew the crystals. S.C., H.W., G.L., X.L., Y.L., K.Y., and A.L. carried out high pressure X-ray diffraction measurements. L.S., Q.W. S.C., J.P.H., and R.J.C. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

41535_2018_134_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information for “Independence of surface state and bulk conductance in three-dimensional topological insulators”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, S., Guo, J., Sidorov, V.A. et al. Independence of topological surface state and bulk conductance in three-dimensional topological insulators. npj Quant Mater 3, 62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0134-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0134-z

This article is cited by

-

Electric field-assisted patterning of few-layer MoTe2 by scanning probe lithography

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2023)

-

Resistivity saturation in Kondo insulators

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Electronic phase separation in multilayer rhombohedral graphite

Nature (2020)