Abstract

The quantum Cramér–Rao bound sets a fundamental limit on the accuracy of unbiased parameter estimation in quantum systems, relating the uncertainty in determining a parameter to the inverse of the quantum Fisher information. We experimentally demonstrate near saturation of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound in the phase estimation of a solid-state spin system, provided by a nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. This is achieved by comparing the experimental uncertainty in phase estimation with an independent measurement of the related quantum Fisher information. The latter is independently extracted from coherent dynamical responses of the system under weak parametric modulations, without performing any quantum-state tomography. While optimal parameter estimation has already been observed for quantum devices involving a limited number of degrees of freedom, our method offers a versatile and powerful experimental tool to explore the Cramér–Rao bound and the quantum Fisher information in systems of higher complexity, as relevant for quantum technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum metrology has emerged as a key quantum technological application. It allows for the improvement of sensors performance, beyond any classically achievable precision, as was demonstrated for instance in squeezed-light-based gravitational wave detectors1. According to the quantum Cramér–Rao bound, the accuracy of any unbiased estimation of an unknown system parameter is limited by the inverse of the quantum Fisher information (QFI)2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Importantly, the QFI only depends on the quantum state and is independent of the estimator; it is a geometric property of a quantum state in parameter space. Thus, for each parameter estimation problem, there potentially exists an optimal quantum measurement that saturates the Cramér–Rao bound. Such fully efficient estimators can be found for classical systems and for small quantum devices upon comparing to theoretical predictions9 or by performing full-state tomography10, which, however, becomes extremely challenging for quantum systems with higher complexity. Consequently, the identification of optimal quantum measurement schemes would highly benefit from a universal method to measure the QFI within the experimental setting. In general, this is a complicated task10,11,12, which requires (by definition) a very precise determination of the “distance” (fidelity) between two quantum states. The quadratic coefficients of several fidelity-like quantities, such as Loschmidt echo13, Hellinger distance11,12, Euclidean distance14 and Bures distance15, are related to the QFI. Hence, in principle, this allows for the evaluation of the QFI from the measurement of these quantities. The corresponding experiments have been demonstrated in an optical system14 and in Bose-Einstein condensates11. In experiment, these quantities are usually determined by the statistical distances of two experimental probability distributions, which are obtained by measuring two quantum states upon an infinitesimally small change of the system parameters4,5,16. Considering these methods, the accurate estimation of the QFI requires precise control of system parameters and the ability to perform multiple measurements or even complete measurements15 on the system; this usually scales exponentially with the system size and remains challenging in many-qubit systems. Furthermore, the lower bound of the QFI can be obtained using quantum optimal control methods17, variational algorithms18,19, and random measurements20,21, which typically require a large number of iterations or measurements.

In this work, we use a nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond to perform a fully efficient phase-estimation quantum measurement by showing saturation of the Cramér–Rao bound. In contrast to a previous study9, where a saturation of the bound was identified through a theoretical estimation of the QFI, we hereby demonstrate saturation through purely experimental means by independently measuring the QFI within our phase-estimation setting. This was achieved by directly probing spectroscopic responses upon weak parametric modulations, a technique which circumvents the stringent requirements of quantum-state tomography and avoids heavy experimental measurement overhead. This has the advantage of offering a more scalable approach to more complex systems. Our method is inspired by a proposal to extract the quantum metric tensor22,23, which was recently implemented in NV centers24,25 and superconducting qubits26. We demonstrate this approach in a Ramsey interferometer, which represents a standard experimental setting for the estimation of an unknown phase parameter. We determine the optimal sensitivity of the phase-parameter estimation through different resource states, and compare these results with their individual QFI. Finally, we demonstrate the applicability of our QFI measurement to the case of coupled qubits, and discuss its relation to entanglement signatures.

Results

Experimental setting

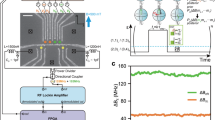

In the experiment, we utilize a nitrogen-vacancy center (NV) in diamond as the quantum sensor. The ground state of the NV center spin has three spin sublevels ms = ±1, 0. By applying an external magnetic field Bz ≃ 510 G along the NV axis, we lift the degeneracy of the spin states ms = ±1 and use the two spin sublevels ms = 0, −1, with states \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|-1\right\rangle\), to form a quantum two-level system with an energy gap ω0 = D − γeBz, where the zero-field splitting is D = (2π)2.87 GHz and γe is the electronic gyromagnetic ratio [Fig. 1(c)]. We use a microwave field to coherently manipulate the NV center spin sate; see Fig. 1(d) for an illustrative Rabi oscillation.

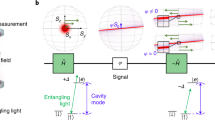

a Ramsey interferometry experiment for the estimation of an unknown phase parameter β. The quantum system is prepared in an initial resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\), the evolution of which results in a phase parameter β. The projective measurement on the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) allows to determine the value of the parameter β. b The QFI of the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) reveals the information content relative to the unknown phase parameter β. The larger QFI (right) implies the better distinguishability between the states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta +d\beta )\right\rangle\) that have an infinitesimal parametric difference dβ → 0. c The energy level structure of the NV center spin in diamond under an external magnetic field. The two-level quantum system is encoded by the ground state spin sublevels ms = 0, −1. d Rabi oscillations: the population in the spin state ms = 0 as a function of time, which facilitates efficient coherent control of the NV center spin state.

Quantum sensing and parameter estimation have been implemented in NV centers using different approaches27,28, inspired by the pioneer proposal and demonstration of magnetometry based on Ramsey spectroscopy29,30,31. Building on those developments, we hereby adopt the standard protocol of a phase-parameter estimation measurement by means of Ramsey interferometry [Fig. 1(a)]. For that purpose, we first initialize the system in a coherent superposition resource state, \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle =\cos (\theta /2)\left|0\right\rangle -\sin (\theta /2)\left|\,-1\right\rangle\), which we evolve into

according to the applied magnetic field. The phase parameter β of \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) can be estimated by performing positive-operator valued measurements (POVM)5,8, \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}=\{{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{j}\}\); as explained below, these are provided by spin-dependent fluorescence measurements (see Supplementary Note 2). The measurement precision is defined as the minimal change of the parameter β that can be detected from the constructed observable above the shot-noise level,

where p is the expectation value of the POVM signal, Δp is the uncertainty associated with the measurement signal. The fundamental limit of the achievable sensitivity of an unbiased estimator is given by the quantum Cramér–Rao bound32,33,34

where \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }\) denotes the QFI, which for pure quantum states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\), is given by4,5

The QFI characterizes the distinguishability of adjacent quantum states over the parameter space [Fig. 1(b)]. The purity of the states in our experiment, and hence the validity of Eq. (4) to capture the QFI, is discussed below. We note that the QFI is related to the real part of the quantum geometric tensor, which can be extracted through coherent dynamical responses22,24.

It is one of the central goals of this work to show the saturation of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound through an independent experimental measurement of the QFI. We extract the QFI by probing coherent dynamical responses of the quantum system upon perturbative parametric modulations22,24. Our measurement protocol is shown in Fig. 2(a). The NV center spin is first initialized in the ms = 0 spin state by applying a green (532 nm) laser pulse, which also polarizes the nitrogen nuclear spin associated with the NV center as we tune the magnetic field close to the excited state level anticrossing (i.e., Bz ≃ 510 Gauss). The subsequent microwave pulse, applied for a duration tθ = (θ/Ω), rotates the NV center spin around the \(\hat{y}\) axis by an angle θ according to the Hamiltonian \({H}_{1}(t)\,=\,({\omega }_{1}/2){\sigma }_{z}+{{\Omega }}\cos ({\omega }_{1}t){\sigma }_{x}\), where ω1 matches the energy gap between the spin sublevels ms = 0, −1 and Ω is the microwave Rabi frequency. The rotation, denoted as Yθ, prepares the NV center spin into the θ-dependent resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\). After the microwave pulse Yθ, the system undergoes a free evolution for a time T, according to an effective Hamiltonian \({H}_{2}^{(e)}\,=\,[({\omega }_{0}-{\omega }_{1})/2]{\sigma }_{z}\), which results in the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\); see Eq. (1). Here, the effective Hamiltonian \({H}_{2}^{(e)}\) is defined in the interaction picture with respect to H0 = (ω1/2)σz. The final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) encodes the information about the phase parameter β = ξT to be estimated, where ξ = ω1 − ω0.

a The pulse sequence for the measurement of the QFI using the NV center spin. The NV center spin is first polarized in the state \(\left|0\right\rangle\) by applying a green (532 nm) laser pulse and the θ-dependent resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\) is prepared via a subsequent microwave pulse Yθ. The interrogation (i.e., the free evolution) for time T results in the parameter-dependent final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\). The parametric modulation via the amplitude and phase-modulated microwave driving is described by the Hamiltonian H[β(t)] with \(\beta (t)=\beta +{a}_{\beta }\cos (\omega t)\). The spin-dependent fluorescence after the inverse evolution, which rotates the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) back to the state \(\left|0\right\rangle\), monitors the coherent transition probability induced by the parametric modulation. b The parameter-modulation induced resonant transition measurement shows the probability that the NV center spin stays in the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) as a function of the modulation frequency ω for a time τ = 450 ns. c The resonant coherent oscillation between the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }^{\perp }(\beta )\right\rangle\) under parametric modulation. The other experiment parameters in (b) and (c) are θ = π/3, A = (2π)15.98 MHz, aβ = 0.1 and ξ = (2π)5.025 MHz. d The QFI measured in our experiment (red circle) is compared with the theoretical prediction (brown curve).

Direct measurement of the QFI

Inspired by the protocol of Ref. 22, we extract the QFI of the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) by monitoring coherent transitions upon parametric modulations. This probing method requires the implementation of the following Hamiltonian

such that the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) approximately corresponds to an eigenstate of \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\). This is achieved by tuning the parameters of the microwave driving field acting on the NV center spin. The key step of our experiment then consists in generating parametric modulations22. To achieve this, we synthesize and calibrate an appropriate microwave driving field with proper amplitude and phase modulations, see Supplementary Note 1 and22,24 using an arbitrary waveform generator as follows

such that the “probing” Hamiltonian retains the form in Eq. (5), but with a time-periodic modulation of the parameter β, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\,\to \,{{{\mathcal{H}}}}[\beta (t)]={{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta +{a}_{\beta }\cos (\omega t))\), where aβ ≪ 1 quantifies the modulation amplitude.

The parametric modulation can induce a coherent transition from the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) to the other orthogonal eigenstate \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }^{\perp }(\beta )\right\rangle\) of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (5)22,24. This transition can be monitored by measuring the probability that the system remains in the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\). In the experiment, without requiring any prior information on the parameter β, we implement an inverse evolution sequence, consisting of two pulses (Yπ and Yπ−θ) separated by a free evolution of duration T [Fig. 2(a)]. Such an inverse evolution rotates the states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }^{\perp }(\beta )\right\rangle\) back to the states \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|-1\right\rangle\), respectively, see Supplementary Note 1. We then measure the population in state \(\left|0\right\rangle\), which equals to the sought population in state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) after the application of the parametric modulation.

The efficiency of the coherent transition induced by the modulation is optimal whenever the modulation frequency matches the energy gap between the states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }^{\perp }(\beta )\right\rangle\). In the experiment, we first perform the modulation-induced-transition measurement for a wide range of modulation frequencies, from which we determine the resonant modulation frequency ω ≃ A; see Fig. 2(b). We then apply the parametric modulation at the resonant frequency, and measure the population in the state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) as a function of the perturbation duration τ; see Fig. 2(c). This data is fitted using a function \({P}_{0}\,=\,[1+\cos ({\nu }_{\theta }t)]/2\), which defines the effective Rabi frequency νθ. From this data, we extract the θ-dependent QFI, \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }(\theta )\), using the relation (see Methods and Supplementary Note 1)

This experimental measurement of the QFI is displayed in Fig. 2(d), which shows excellent agreement with the theoretical prediction \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }\,=\,{\sin }^{2}\theta\). In particular, it clearly demonstrates the dependence of the QFI on the initial resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\). The precision of our measurement relies on the accuracy of the engineered Hamiltonian \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\) and on the determination of the effective Rabi frequency νθ. The imperfection in the interrogation step [Fig. 2(a)] may result in a mixed state rather than a pure state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\); this would decrease the contrast of the Rabi oscillations and affect the measurement accuracy. By reconstructing the density matrix through projective measurements, we estimate the state fidelity to be above 95% in our experiment, see Supplementary Note 2, which is evidenced by the good agreement between our results and the theoretical predictions.

Reaching the quantum Cramér–Rao bound

The QFI measurement enables us to experimentally show that our phase-parameter estimator exhibits optimal performance by saturating the quantum Cramér–Rao bound in Eq. (3). In order to analyze the relation between the measurement precision and the QFI, we now determine the measurement sensitivity for the estimation of the parameter β within our Ramsey interferometry experiment. To do so, we first apply the rotation Yθ on the NV center spin qubit to prepare the initial state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\); the system then evolves freely for a time T = β/ξ. To build an estimator of the parameter β, we apply a rotation Yα, which is equivalent to a projective measurement \({P}_{\alpha }\,=\,\left|{\phi }_{\alpha }\right\rangle \left\langle {\phi }_{\alpha }\right|\) on the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\), where \(\left|{\phi }_{\alpha }\right\rangle =\cos (\alpha /2)\left|0\right\rangle +\sin (\alpha /2)\left|-1\right\rangle\) [Fig. 1(a)]. The observable of interest is then provided by the function \(p(\beta ;\theta ,\alpha )\,=\,\left\langle {\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right|{P}_{\alpha }\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\), from which we aim to estimate the parameter β with optimal accuracy [Eq. (3)]. We tune the free evolution time such that the parameter β = ξT is close to the working point where the best sensitivity occurs, i.e., β ≃ π/2 where the slope ∂p/∂β is maximal [Fig. 3(a)].

a The Ramsey interferometry measurement signal \(p\,=\,\left\langle S\right\rangle\). The measurement data allows us to obtain the susceptibility χα = ∂p/∂β of the measurement signal close to the working point β = π/2. The error bars represent the uncertainty of the parameter estimation \({{\Delta }}p={[\left\langle {S}^{2}\right\rangle -{\left\langle S\right\rangle }^{2}]}^{1/2}\) with the number of repetitions N = 9. The parameters are θ = π/3, α = π/2, ξ = (2π)2.27 MHz and A = (2π)11.34 MHz. b The uncertainty of the parameter estimation Δs as a function of the number of repetitions N can be fitted by a function of the form \({{\Delta }}p={{{\Delta }}}_{0}/\sqrt{N}\) (green curve). c The optimal measurement sensitivity δβ (achieved by the projective measurement Pα with α = π/2) by using different θ-dependent resource states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\). Inset: The sensitivity δβ, achieved by applying the projective measurement Pα as a function of α when θ = π/2 and β = π/2, shows that the optimal measurement sensitivity in our Ramsey interferometry experiment is obtained when α = π/2. The green curve is obtained from numerical simulation, see further details in Fig. S4. d The linear relation \(\delta \beta \propto 1/\sqrt{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }}\), where \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }\) is the quantum Fisher information; the measured proportionality factor is 1.041 ± 0.036. The number of repetitions in (c, d) is N = 1. The curves in (a, c, d) are theoretical predictions.

Ramsey parameter estimation can, in principle, achieve optimal efficiency. However, in practice, this would require an ideal projective measurement of the sensor upon reaching the shot-noise limit. Such an ideal measurement cannot be perfectly performed, due to a limited collection efficiency or other types of measurement noise (e.g., Gaussian fluctuations in the photon number). To overcome this limitation, one may adopt the technique of single-shot readout35,36,37,38, which consists in setting a threshold ns of photon number to distinguish the state \(\left|{m}_{s}=-1\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{m}_{s}=0\right\rangle\) and assign a value s = 0 or 1 depending on whether nj > ns or nj < ns.

In our experiment, the observable \(p(\beta ;\theta ,\alpha )\,=\,\left\langle {\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right|{P}_{\alpha }\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\) is estimated from the collected photons of a fluorescence signal (see Methods). Due to the limited collection efficiency, the signal photons are accumulated over many sweeps of an experimental sequence, which constitutes one experimental run of our measurement. In the j-th run, based on the photon number nj detected from the rotated spin state \({Y}_{\alpha }\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\), we define the ratio pj = (nj − n1)/(n0 − n1) where n0 and n1 are the average photon numbers obtained from the bare spin states ms = 0 and ms = −1, respectively. We proceed to assign a measurement value sj = k + 1 or k according to the probabilities \({p}_{j}^{(k)}={p}_{j}-k\) and \(1-{p}_{j}^{(k)}\) for ⌊pj⌋ = k, see Methods. This allows us to introduce a quantity \(S\,=\,(1/N)\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N}\,{s}_{j}\), whose expectation value yields the desired function \(\left\langle S\right\rangle \,=\,p(\beta ;\theta ,\alpha )\). Using this quantity, we can construct an estimator for the parameter β, and find that the influence of measurement noise on S is eliminated to a large extent (apart from the shot-noise), which also provides a data analysis alternative for the spin readout techniques of NV centers35,36,37,38, see Methods. The data obtained from repeated measurements [Fig. 3(a)] allows us to determine the slope of the signal, which is defined as \({\chi }_{\alpha }\,=\,\partial p/\partial \beta \,=\,\left[p(\beta +d\beta )-p(\beta )\right]/d\beta\). From the experimental data, we can also extract the measurement uncertainty Δp associated with the observable S; see Fig. 3(b). We note that the uncertainty scales with the number of repetitions N as \({{\Delta }}p\,=\,{{{\Delta }}}_{0}/\sqrt{N}+{\xi }_{0}\), see Methods. The first term arises from the shot-noise with Δ0 = [p(1−p)]1/2, while the second term ξ0 represents the contribution from the measurement fluctuation that cannot be averaged out. We remark that other advanced readout techniques, such as the single-shot measurement based on spin to charge conversion39, can further reduce such measurement noise (see Eq. ((18), (21)) in Methods) and enhance the sensitivity.

We first compare the sensitivity δβ = Δp/χα obtained by projective measurements over different bases Pα. The experimental results shown in the inset of Fig. 3(c) demonstrate that the optimal measurement sensitivity is obtained when α = π/2, which agrees with the theoretical prediction (see Supplementary Note 2), \({(\delta \beta )}^{2}\,=\,[1-{(\cos \beta \sin \theta )}^{2}]/| \sin \beta \sin \theta {| }^{2}\). The slight deviation arises from other sources (apart from shot noise). The measurement precision also depends on the angle θ of the resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\), which accounts for the QFI of the final state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(\beta )\right\rangle\): we proceed by determining the optimal measurement sensitivity with different resource states \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\) in view of testing the quantum Cramér–Rao bound in Eq. (3). It can be seen from the results shown in Fig. 3(c) that the optimal measurement sensitivity improves as the angle θ approaches π/2, i.e., when the resource state \(\left|{\psi }_{\theta }(0)\right\rangle\) becomes a maximally coherent superposition state. We remark that the result in the inset of Fig. 3(c) is skewed as the pulse Yα is off-resonant; the influence of the corresponding detuning is the asymmetry observed around α = π/2. Moreover, the optimal measurement sensitivity verifies the quantum Cramér–Rao bound [Eq. (3)], as we finally demonstrated in Fig. 3(d).

Generalization to entangled qubits

Single NV centers in diamond allow to perform quantum sensing with unprecedented spatial resolution40. In this context, the saturation of the Cramér–Rao bound is of particular importance as it may allow quantum sensing with unparalleled accuracy. Still, it is a natural question whether our QFI measurement can also be extended to the multi-qubit case, where quantum entanglement can provide a further key factor to increase the performance of a quantum sensor.

For that purpose, we now demonstrate the applicability of our parametric modulation scheme in view of measuring the QFI in a realistic two-qubit correlated system24, which consists of an NV center and a nearby strongly coupled 13C nuclear spin via the hyperfine interaction. The effective Hamiltonian of the system is given by (see Supplementary Note 3)

where σ and τ denote the Pauli matrices of the NV center and of the 13C nuclear spin, respectively. We denote the four eigenstates of this Hamiltonian as \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{1}\right\rangle\), \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{3}\right\rangle\), \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{3}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{4}\right\rangle\), with their associated eigenvalues ϵ1 < ϵ2 < ϵ3 < ϵ4. Similarly to the single qubit case treated above, we are interested in the quantum-parameter-estimation problem associated with the parameter β, and in particular, to the related QFI. Without loss of generality, we focus our study on the QFI contained in the lowest-energy eigenstate \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{1}\right\rangle\).

Considering the parametric modulation \(\beta (t)=\beta +a\cos (\omega t)\), the QFI can be related to the three Rabi frequencies νk associated with the induced transitions between the ground state \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{1}\right\rangle\) and the other three eigenstates \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{k}\right\rangle\) according to

where ωk = ϵk − ϵ1. We have performed a numerical simulation of this setting and we present the results in Fig. 4(a). We find that the QFI of the ground state reaches its peak value when the energy of the corresponding eigenstate becomes very close to another eigenenergy, in the form of an avoided crossing (see Supplementary Note 3). In this situation, a small variation of the parameter (i.e., a perturbation) would indeed result in a significant change of the ground state. Importantly, this increase of the QFI is accompanied with a significant growth of entanglement, as quantified by the concurrence41, as we demonstrate in Fig. 4(b). The connection between the QFI and the entanglement of such a coupled-qubit setting (see Supplementary Note 3) is known to arise from the level anticrossing42,43, which represents a general feature in systems beyond the single-qubit context. These results suggest that a large QFI is linked to strong entanglement upon measuring the QFI based on parametric modulations as introduced here. We remark that the proposed protocol can be extended to experimentally determine the QFI of many-body quantum systems by measuring the excitation rate under parametric modulation following the idea as presented in Ref. 22. The approach does not require full state tomography, which is an experimentally demanding task for a multi-qubit system. The present technique which allows us to estimate the QFI, and hence the quantum Cramér–Rao bound, will be helpful in resolving the challenging task of determining the optimal measurement for many-body ground states that can reach the bound.

a The QFI \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\beta }\) of the ground state \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{1}\right\rangle\). The data points obtained from the simulation of the experiments agree well with the exact theoretical values (solid lines). b The concurrence C of ground state \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}_{1}\right\rangle\). The parameters we use are A⊥ = (2π)2.79 MHz, A∥ = (2π)11.832 MHz and Bz = 504 G. The values of the modulation strength, ak, are chosen such that the Rabi frequency of the induced coherent oscillation is much smaller than the corresponding energy gaps, see Ref. 22.

Discussion

In this work, we have introduced an experimental technique to measure the QFI in a solid-state spin system based on spectroscopic responses. Importantly, this approach does not require full state tomography, and it can therefore be potentially applied to more complex systems. We have shown that this technique offers a genuine experimental probe of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound saturation, which does not rely on any theoretical knowledge, hence providing a universal tool to identify fully efficient estimators. The presented technique provides a versatile tool to explore the fundamental role of the QFI in various physical scenarios, including quantum metrology, but also entanglement properties of many-body quantum systems23,44 and the quantum speed limit in the context of optimal control45,46,47,48,49.

Methods

QFI and parametric modulation-induced transition

At first we can rewrite the QFI (4) of \(\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle\) which is the n-th eigenstate of Hamiltonian \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\), i.e., \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle ={E}_{n}(\beta )\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle\)

with the following identity

Now, we consider the weak parametric modulation i.e., aβ ≪ 1, the time-periodic Hamiltonian can be expanded as

According to time-dependent perturbation theory, if the system is initialized in the eigenstate state \(\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle\), the second term will excite the system to another eigenstate \(\left|{\psi }_{k}(\beta )\right\rangle\) under a resonate condition ω = ωkn = Ek(β) − En(β). In the subspace spanned by \(\{\left|{\psi }_{k}(\beta )\right\rangle ,\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle \}\), the parametric modulation Hamiltonian can be written as

with \({{{\Omega }}}_{kn}={a}_{\beta }\left\langle {\psi }_{k}(\beta )\right|{\partial }_{\beta }{{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle\). This Hamiltonian induces a Rabi oscillation between \(\left|{\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{\psi }_{k}(\beta )\right\rangle\) with the corresponding Rabi frequency \({\nu }_{k}=| {{{\Omega }}}_{kn}| ={a}_{\beta }| \left\langle {\psi }_{n}(\beta )\right|{\partial }_{\beta }{{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\beta )\left|{\psi }_{k}(\beta )\right\rangle |\), and the QFI becomes22,24

which gives the two specific forms ((7), (9)) in the qubit system.

Quantum parameter estimation protocol

The sensitivity of quantum parameter estimation is dependent on the measurement protocol. In the experiment, we perform projective measurement on the NV center spin that is described by the operator \({\hat{P}}_{\alpha }=\left|{\phi }_{\alpha }\right\rangle \left\langle {\phi }_{\alpha }\right|\) with the basis state \(\left|{\phi }_{\alpha }\right\rangle =\cos (\alpha /2)\left|0\right\rangle +\sin (\alpha /2)\left|-1\right\rangle\). We count the number of photons in the first 300 ns of the laser pulse as the signal photons. Due to the limit of collection efficiency, the signal photons are accumulated over a number of sweeps of an experimental measurement sequence, which constitutes one experiment run of measurement. We denote the averaged photon number obtained from the bare spin state ms = 0 and ms = −1 as n0 and n1 respectively. We introduce a variable s = 1/0 to represent the spin state ms = 0/ms = −1. For the NV center spin system, the signal photons are spin-dependent, namely (n0 − n1)/n0 ≃ 30%, see Fig. 5(a). For a quantum state ρ with the state \(\left|0\right\rangle\) population \(p=\left\langle 0\right|\rho \left|0\right\rangle\), the number of photons nj collected in the j-th experiment run fluctuates and follows the distribution \({n}_{j} \sim p{{{\mathcal{N}}}}({n}_{0},{\sigma }_{0}^{2})+(1-p){{{\mathcal{N}}}}({n}_{1},{\sigma }_{1}^{2})\), see an example shown in Fig. 5(b). According to the properties of the normal distribution, the random variable pj = (nj − n1)/(n0 − n1) follows the probability distribution Q(pj)

where Δn = n0 − n1 and \({\tilde{\sigma }}_{m}={\sigma }_{m}/{{\Delta }}n,\,m=0,1\). Q(pj) is shown in Fig. 6 and is divided into a series of intervals by the integers k = ⌊pj⌋.

a shows the histogram of the number of photons collected from the spin state \(\left|-1\right\rangle\) (red) and \(\left|0\right\rangle\) (blue) with the averaged number of photons n1 and n0 respectively. b shows the histogram of the number of photons collected while the NV center spin is in the superposition state \(\left|+\right\rangle =(1/\sqrt{2})(\left|0\right\rangle +\left|-1\right\rangle )\).

Based on the distribution Q(pj), we proceed to assign a measurement value sj = k + 1 or k according to the probabilities \({p}_{j}^{(k)}={p}_{j}-k\) and \(1-{p}_{j}^{(k)}\) in the kth interval. This allows us to construct a quantity as \(S=(1/N)\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N}{s}_{j}\), the expectation value of which is

The variance of the quantity S is given by

The first term can be calculated as

We define pj = ⌊pj⌋ + δj = k + δj with δj ∈ [0, 1), and Fk can be write as

It can be seen that for all k ∈ Z, Fk ≥ 0, and if and only if k = 0, Fk = 0. Therefore, Eq. (18) satisfies

and the variance of the quantity S is bounded by the shot noise

If the distribution Q(pj) is strictly localized in the zeroth (k = 0) interval, i.e the black areas in Fig. 6 are negligible, all the components Fk ≃ 0. Therefore, the variance of the observable S achieves the shot noise

In our experiment, the measurements are performed at the working points β = π/2, which makes p ≃ 1/2 and

with \(\sigma =(1/2)\sqrt{{\tilde{\sigma }}_{0}^{2}+{\tilde{\sigma }}_{1}^{2}}\). The distribution of pj obtained in our experiment satisfies \(\sqrt{{\tilde{\sigma }}_{0}^{2}+{\tilde{\sigma }}_{1}^{2}}\simeq 1/2\), which guarantees a more than 95% confidence interval of k = 0 (see Fig. 6).

Furthermore, we note that

thus we can construct the following estimator for the parameter β as

where N0 and N1 represents the number of sj = 0 and 1 respectively. With α = π/2, the estimator becomes

The precision can be written as

which gives the optimal sensitivity with α = π/2 satisfying the quantum Cramér–Rao bound at the working point β = π/2.

Data availability

The data generated during this work are available from the corresponding author J.-M.C upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for generating the plots are available from the corresponding author J.-M.C. upon reasonable request.

References

L. S. Collaboration A gravitational wave observatory operating beyond the quantum shot-noise limit. Nat. Phys. 7, 962–965 (2011).

Cramér, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics, volume 9, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1946).

Rao, C. R. Information and the Accuracy Attainable in the Estimation of Statistical Parameters, 235–247 (Springer, New York, 1992).

Braunstein, S. L. & Caves, C. M. Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439 (1994).

Braunstein, S. L., Caves, C. M. & Milburn, G. J. Generalized uncertainty relations: theory, examples, and Lorentz invariance. Ann. Phys. 247, 135–173 (1996).

Petz, D. & Ghinea, C. Introduction To Quantum Fisher Information, 261–281, (World Scientific, Singapore, 2011).

Tóth, G. & Apellaniz, I. Quantum metrology from a quantum information science perspective. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 47, 424006 (2014).

Sidhu, J. S. & Kok, P. Geometric perspective on quantum parameter estimation. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 014701 (2020).

Brida, G. et al. Experimental estimation of entanglement at the quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 100501 (2010).

Lu, Y.-N. et al. Observing information backflow from controllable non-Markovian multi-channels in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 210502 (2020).

Strobel, H. et al. Fisher information and entanglement of non-Gaussian spin states. Science 345, 424–427 (2014).

Li, Y. & Li, W. D. Reasonable method to extract Fisher information from experimental data. Physica A 514, 606–611 (2019).

Macrì, T., Smerzi, A. & Pezzè, L. Loschmidt echo for quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. A 94, 010102(R) (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Detecting metrologically useful asymmetry and entanglement by a few local measurements. Phys. Rev. A 96, 042327 (2017).

Fröwis, F., Sekatski, P. & Dür, W. Detecting large quantum fisher information with finite measurement precision. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 090801 (2016).

Pezzè, L., Li, Y., W.-D., L. & Smerzi, A. Witnessing entanglement without entanglement witness operators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11459–11464 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Probe optimization for quantum metrology via closed-loop learning control. npj Quantum Inf. 6, 62 (2020).

Beckey, J. L., Cerezo, M., Sone, A. & Coles, P. J. Variational Quantum Algorithm for Estimating the Quantum Fisher Information. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013083 (2022).

Meyer, J. J., Borregaard, J. & Eisert, J. A variational toolbox for quantum multi-parameter estimation. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 89 (2021).

Yu, M. et al. Experimental estimation of the quantum Fisher information from randomized measurements. Phys. Rev. Research 3, 043122 (2021).

Rath, A., Branciard, C., Minguzzi, A. & Vermersch, B. Quantum Fisher information from randomized measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 260501 (2021).

Ozawa, T. & Goldman, N. Extracting the quantum metric tensor through periodic driving. Phys. Rev. B 97, 201117 (2018).

Ozawa, T. & Goldman, N. Probing localization and quantum geometry by spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 032019 (2019).

Yu, M. et al. Experimental measurement of the complete quantum geometry of a solid-state spin system. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 254–260 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. A synthetic monopole source of Kalb-Ramond field in diamond. Science 375, 1017–1020 (2022).

Tan, X.-S. et al. Experimental measurement of the quantum metric tensor and related topological phase transition with a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 210401 (2019).

Rondin, L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 056503 (2014).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Taylor, J. M. et al. High-sensitivity diamond magnetometer with nanoscale resolution. Nat. Phys. 4, 810–816 (2008).

Maze, J. R. et al. Nanoscale magnetic sensing with an individual electronic spin in diamond. Nature 455, 644–647 (2008).

Balasubramanian, G. et al. Nanoscale imaging magnetometry with diamond spins under ambient conditions. Nature 455, 648–651 (2008).

Helstrom, C. W. (editor). Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory, (Academic, New York, 1976).

Holevo, A. Probabilistic and Statistical Aspects of Quantum Theory, (Springer, New York, 2011).

Hayashi, M. Quantum Information Geometry and Quantum Estimation, 253–322, (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2017).

Neumann, P. et al. Single-shot readout of a single nuclear spin. Science 329, 542–544 (2010).

Robledo, L. et al. High-fidelity projective read-out of a solid-state spin quantum register. Nature 477, 574–578 (2011).

Dréau, A., Spinicelli, P., Maze, J.R., Roch, J.-F. & Jacques, V. Single-shot readout of multiple nuclear spin qubits in diamond under ambient conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 060502 (2013).

Liu, G.Q. et al. Single-shot readout of a nuclear spin weakly coupled to a nitrogen-vacancy center at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 150504 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. High-fidelity single-shot readout of single electron spin in diamond with spin-to-charge conversion. Nat. Commun. 12, 1529 (2021).

Grinolds, M. S. et al. Subnanometre resolution in three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of individual dark spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 279–284 (2014).

Wooters, W. K. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phy. Rev. Lett 80, 2245 (1998).

Berkley, A. J. et al. Entangled macroscopic quantum states in two superconducting qubits. Science 300, 1548–1550 (2003).

Smirnov, A. Y. & Amin, M. H. Ground-state entanglement in coupled qubits. Phys. Rev. A 88, 022329 (2013).

Hauke, P., Heyl, M., Tagliacozzo, L. & Zoller, P. Measuring multipartite entanglement through dynamic susceptibilities. Nat. Phys. 12, 778–782 (2016).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum limits to dynamical evolution. Phys. Rev. A 67, 052109 (2003).

Taddei, M. M., Escher, B. M., Davidovich, L. & deMatosFilho, R. L. Quantum speed limit for physical processes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 050402 (2013).

del Campo, A., Egusquiza, I. L., Plenio, M. B. & Huelga, S. F. Quantum speed limits in open system dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 050403 (2013).

Pires, D. P., Cianciaruso, M., Céleri, L. C., Adesso, G. & Soares-Pinto, D. O. Generalized geometric quantum speed limits. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021031 (2016).

Kolodrubetz, M., Sels, D., Mehta, P. & Polkovnikov, A. Geometry and non-adiabatic response in quantum and classical systems. Phys. Rep. 697, 1–87 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11874024, 11690032), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0306600), the Open Project Program of Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics (No. 2019WNLOKF002). T.O. is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18H05857, JST PRESTO Grant Number JPMJPR19L2, JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR19T1, and the Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences Program (iTHEMS) at RIKEN. N.G. is supported by the ERC Starting Grant TopoCold and the Fonds De La Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS) (Belgium). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 853443), and M.H. further acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft via the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. and Y.L. contributed equally to this work. M.Y., P.-C.Y., M.-S.G., Q.-Y.C., J.-M.C. performed the experiments, Y.L., S.-L.Z., H.-B.L., M.H., T.O., N.G., J.-M.C. performed theoretical analysis and simulation, Y.L., M.H., T.O., N.G., J.-M.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, and agreed with the conclusions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, M., Liu, Y., Yang, P. et al. Quantum Fisher information measurement and verification of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound in a solid-state qubit. npj Quantum Inf 8, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00547-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00547-x

This article is cited by

-

Experimental investigation of geometric quantum speed limits in an open quantum system

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Quantum Fisher information for two-qubit XY spin-chain: individual characterization of different parameters

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2023)