Abstract

The future envisaged global-scale quantum-communication network will comprise various nodes interconnected via optical fibers or free-space channels, depending on the link distance. The free-space segment of such a network should guarantee certain key requirements, such as daytime operation and the compatibility with the complementary telecom-based fiber infrastructure. In addition, space-to-ground links will require the capability of designing light and compact quantum devices to be placed in orbit. For these reasons, investigating available solutions matching all the above requirements is still necessary. Here we present a full prototype for daylight quantum key distribution at 1550 nm exploiting an integrated silicon-photonics chip as state encoder. We tested our prototype in the urban area of Padua (Italy) over a 145 m-long free-space link, obtaining a quantum bit error rate around 0.5% and an averaged secret key rate of 30 kbps during a whole sunny day (from 11:00 to 20:00). The developed chip represents a cost-effective solution for portable free-space transmitters and a promising resource to design quantum optical payloads for future satellite missions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)1,2,3,4 is the most advanced application of quantum information science, continuously improving in terms of new protocols5,6 and experimental realizations7,8,9,10. The potential of QKD is to allow secure communication between any two points on Earth. Depending on the link distance, the quantum channel is established through fiber-based or free-space quantum communication (QC). Despite the recent demonstrations also realized in satellite-to-ground links11,12,13,14, free-space QKD-technology is currently limited and cannot compete with its fiber-based counterpart7,15,16,17,18. Hence, in the vision of a continental-scale quantum network (or quantum internet)19,20,21,22,23 where both types of link are required to jointly operate, certain key requirements for free-space QC can be formulated, as (i) full-day functionality, (ii) compatibility with standard fiber-based technology at telecom wavelength, and (iii) the achievement of stable coupling of the free-space signal into a single-mode fiber (SMF).

Regarding (i), the background noise due to sunlight poses a serious limitation on the achievable performance of day-time free-space QC, limiting most of the demonstrations obtained so far to night-time. For this reason, various studies have focused on the feasibility of daylight QKD24,25,26,27,28,29. Most of them exploited light in the 700–900 nm band, which allows for a good atmospheric transmission, and to exploit commercial low-noise silicon-based single-photon avalanche diodes (SPADs). To reduce the background noise due to the Sun and to maintain, at the same time, a good efficiency in the atmospheric transmission, the choice to use light signals in the telecom C-band (around 1550 nm) has only very recently started to be investigated28,29.

Moving the operating wavelength to the telecom band comes with (at least) two advantages. Firstly, given the availability of commercial-off-the-shelf components, using a working wavelength in the C-band is the standard choice in fiber-based optical (classical and) QC realizations, hence fulfilling the requirement (ii). This opens up the possibility of realizing a hybrid free-space to fiber system. For instance, it is particular important in a scenario where the ground station, collecting the photons from a satellite, is separated from the location of the detection stage. Secondly, it is compatible with integrated silicon photonics30,31,32,33, which represents a promising choice for designing light, compact, scalable and low power-consuming devices suitable for portable QKD transmitters and to design satellite optical payloads34,35.

Furthermore, to match the requirement iii) it is necessary to actively compensate for the optical aberrations (at least the beam wander and angle-of-arrival fluctuation) introduced by atmospheric turbulence, which is experimentally challenging36,37. However, a stable coupling of the light signal into a SMF has the advantage of allowing the use of commercially available superconductive nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs), which represent the standard for fiber-based state-of-the-art QKD demonstrations7,10,16.

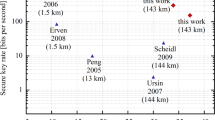

Here we address the requirements outlined above presenting a QC-system named “QCoSOne” (acronym for “Quantum Communication for Space-One”), which realizes free-space daylight QKD at 1550 nm. We exploited integrated silicon-photonics technology to realize a portable state encoder with decoy- and polarization-modulation on a single chip, to implement the 3-state 1-decoy QKD protocol introduced in ref. 5. Moreover, the integrated QKD encoder has been put in a rugged package, designed and realized to the purpose in-house, making it ready for use in the field. We exploited commercially available wavelength filters (with ≲ 1 nm of bandwidth) and SNSPDs at the detection state. We reached a stable SMF coupling of the qubit stream over a 145m-long free-space link (Fig. 1a) by means of an active correction of the first order aberrations that allowed us to successfully perform QKD in daylight continuously from 11:00 to 20:00 (Central European Summer Time, CEST). We measured a quantum bit error rate (QBER) around 0.5% in most of the runs, obtaining a final secret-key-rate (SKR) up to 65 kbps after finite-key analysis. To the best of our knowledge, we obtained the lowest QBER ever reported in a free-space trial, and our experiment represents the longest-lasting demonstration of daylight QKD at 1550 nm, as well as the first daylight experiment where a chip-based QKD state encoder is coupled to a free-space channel in an actual field trial. Our result represents one step towards the demonstration of a seamless joint satellite-fiber quantum network at the telecom band.

a Location of the field test in Padua. Map Data from Google [©2019 Google]. b Alice’s terminal with the sketch of the QKD source and chip schematic. DM dichroic mirror, CAM camera. c Bob’s terminal with the scheme of the state analyzer. d Picture of the packaged chip soldered to the external control board with the input/output fiber array.

Results

Description of QCoSOne prototype

A comprehensive sketch of the experimental setup is presented in Fig. 1. The QKD source and detection units, at Alice’s and Bob’s side respectively, are linked by a free-space channel established between the Department of Information Engineering (DEI) and the Luxor Laboratory (LUXOR) (Fig. 1a). Alice’s transmitter telescope (Fig. 1b) is an achromatic refractor with an aperture diameter of 12 cm, mounted on a motorized tripod and placed at DEI building. Bob’s receiving telescope (Fig. 1c) is a Cassegrain reflector with an equivalent focal length of 5000 mm comprising a primary mirror with a diameter of 31.5 cm, mounted on a fixed support located at LUXOR.

We focused and coupled the free-space signal beam down to the 5 μrad of half-angle field-of-view (FOV) of the receiver. In order to do this, we developed a closed-loop feedback control at Bob’s side, based on the use of a fast-steering mirror (FSM) [SmarAct] to correct for lower-order aberrations (i.e., tip-tilt) induced by turbulence. The feedback signal is provided by the centroid of an auxiliary beacon laser at 1064 nm acquired by a position-sensitive detector (PSD). We reached an average coupling efficiency into the SMF (just after the receiving telescope) of around 8.5%, which is in line with analogous systems based only on tip-tilt correction28. More details on the pointing, acquisition and tracking (PAT) system and its performance, as well as the estimation of the impact of turbulence on our experiment, are presented in the Methods section.

The inset of Fig. 1b shows the sketch of the QKD source. A gain-switched distributed feedback (DFB) laser source outputs a 50 MHz stream of phase-randomized pulses (with 500 ps of full-width-at-half-maximum, FWHM) at 1550 nm of wavelength. Such pulses are coupled in and out of a state encoder realized in a silicon-based photonic integrated circuit (PIC) via a standard 8-channel SMF-array glued to the PIC’s grating couplers (GCs). The PIC was designed in-house and realized exploiting the Europractice IC Service38 (http://www.europractice-ic.com/index.php) offered by the IMEC foundry.

The PIC comprises several interferometric structures exploiting standard building blocks provided by the foundry, e.g., multi-mode interference (MMI) devices acting as 50/50 beam splitters, slow thermo-optics modulators (TOMs, ~ kHz of bandwidth, DC modulation) and fast carrier-depletion modulators (CDMs, ~ GHz of bandwidth, RF modulation), which are realized in a reverse biased p-n junction on the silicon waveguide. More details on the working principle of the components of the PIC and on the fabrication process can be found in refs. 31,39,40.

The size of the PIC is about 5 mm × 5 mm, while the complete package is compact within a total volume of 1.2 cm × 1.5 cm × 1.2 cm. A picture of the packaged PIC soldered to a standard 7 cm × 8 cm control board is presented in Fig. 1d. The package has been designed, developed and assembled to the purpose in-house (featuring 20 DC and 6 RF ports), so as to make it rugged, portable and easily usable in field experiments. The capability of compacting and integrating the devices needed to prepare the quantum states down to such a small volume represents an attractive choice for designing portable transmitters and payloads for satellite QC41,42. It is worth noting that, even if a quantum random number generator (QRNG) is not included on the PIC, a compact QRNG scheme, as the one presented in ref. 43, could be embedded on the same chip, thus requiring the same volume for the package.

The first interferometric structure realizing a Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI) is used to obtain the amplitude modulation of the pulses according to the chosen QKD protocol (see ref. 5 and Methods for more details), which requires preparing pulses with two different intensity levels, or mean photon number per pulse μ1 and μ2, with μ1 > μ2. The ratio μ1/μ2 is set by both the DC-bias of the TOMs as well as by the RF signal amplitude sent to the CDMs of the MZI. In particular, if no RF signal is applied, the amplitude is set to μ1, while, by applying an RF signal, the μ2 intensity is sent.

The second structure allows to realize the polarization modulation, by exploiting an inner MZI, followed by two external CDMs (CDM1 and CDM2 in Fig. 1b) ending in a 2-dimensional grating coupler (GC2d). The GC2d converts the path-encoded information used within the PIC into the polarization-encoded information at the output-SMF. Referring to the Bloch sphere, the colatitude θ of the produced polarization state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle =\cos (\theta /2)\left|H\right\rangle +{e}^{i\varphi }\sin (\theta /2)\left|V\right\rangle\) is controlled by acting on the internal MZI, whereas the longitude φ is set by acting on the external phase modulators. Therefore, by voltage biasing the TOMs of the inner MZI, the balanced superposition of horizontal and vertical polarization \(\left|+\right\rangle =(\left|H\right\rangle +\left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) is created. If no RF signal is applied, the output state remains \(\left|+\right\rangle\), whereas, by applying an RF signal on the external CDMs, a π/2 phase shift can imposed to either arm, respectively creating the states \(\left|L\right\rangle =(\left|H\right\rangle -i\left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) or \(\left|R\right\rangle =(\left|H\right\rangle +i\left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). In this way, we obtained the three states required by the protocol for the key-generation basis \(Z=\{\left|0\right\rangle ,\left|1\right\rangle \}\), where \(\left|0\right\rangle := \left|L\right\rangle\), \(\left|1\right\rangle := \left|R\right\rangle\), and the control basis \(X=\{\left|+\right\rangle ,\left|-\right\rangle \}\), with \(\left|\pm \right\rangle := (\left|H\right\rangle \pm \left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). Each produced state is characterized by an extinction ratio (ER), i.e., the ratio between the optical power in two orthogonal polarizations, of 30 dB, which corresponds to an intrinsic, or optical, quantum bit error rate (QBERopt1) of 0.1% for our integrated source. It is worth noticing that this is the lowest instrinsic QBER ever reported for a silicon-based PIC implementing both polarization and intensity modulations in the same chip30,31,32.

The pulses exiting from the PIC are spectrally filtered by a commercial dense wavelength-division-multiplexing (WDM) filter with 100 GHz of channel spacing, corresponding to a bandwidth of 0.8 nm centered around 1550.94 nm. Then, they pass through a variable optical attenuator (VOA) to set μ1 to the desired level, and a 99/1 fiber beam splitter (BS). The 1% output is directed to an InGaAs/InP gated SPAD [Micro Photon Devices44] to monitor in real-time the intensity level of the pulses, while the 99% output is directed to the transmitting telescope together with the additional beacon lasers at 1064 nm and 1545 nm used by the PAT system.

We made Alice generate the polarization pulses with basis-probability \({p}_{A}^{Z}=0.9\) and \({p}_{A}^{X}=0.1\) and intensities \({\mu }_{1}^{Z}=0.56\), \({\mu }_{2}^{Z}=0.27\), \({\mu }_{1}^{X}=0.69\), and \({\mu }_{2}^{X}=0.33\) at the aperture of the transmitting telescope, with decoy-probability \({p}_{{\mu }_{1}}=0.7\) and \({p}_{{\mu }_{2}}=0.3\). These working parameters are close to optimal for a total attenuation ranging from 20 to 30 dB, a QBER of the order of 1% and a number of sifted bits nZ ≳ 108, as we expected in our experiment according to our simulations and ref. 5. It is worth noting that the possibility of using different intensity levels for the two bases without losing security (as discussed in ref. 45) is particularly interesting when dealing with non-ideal CDMs, since they typically incur phase-dependent losses translating into polarization-dependent amplitude levels of the QKD pulses.

The random bits used for running the protocol are obtained from the source-device-independent quantum random number generator based on the heterodyne measurement of the electromagnetic field described in46. An evaluation board [ZedBoard by Avnet] with a System-on-a-chip (SOC) is used to control the source. The board clock is locked to a 10 MHz clock from Alice’s GPS module. The field-programmable-gate-array (FPGA) side of the SOC is designed in order to produce the electrical pulses for triggering the laser, the RF signals driving the CDMs and the gating signal for the SPAD.

Bob’s SMF-based state analyzer, shown in the inset of Fig. 1c, is connected to the receiving telescope by a 40m-long SMF. The state analyzer comprises first a dense WDM filter (matched with the one of the source) to select the photons coming from Alice. Due to the insertion losses of the WDM filter, the mean coupling efficiency of the quantum signal at 1550 nm is reduced to 6% (12 dB), as measured just after it. Then a 90/10 fiber BS sets the detection probabilities of the two measurement bases to \({p}_{B}^{Z}=0.9\) and \({p}_{B}^{X}=0.1\). Each output arm of the BS is connected to an automatic polarization controller (APC) and a polarizing beam splitter (PBS). The four outputs are sent to four SNSPDs [ID281 by ID-Quantique] cooled to 0.8 K. A manual polarization controller (PC) at the input of every detector is used to optimize the detection efficiency. This is around 85% for the detectors in the Z basis, whereas it is 90 and 30% for the \(\left|+\right\rangle\) and \(\left|-\right\rangle\) detectors, respectively. As discussed in refs. 47,48, we randomly discarded some detections in post-processing in order to balance the different efficiencies. All the detectors are affected by about 200 Hz of intrinsic dark count rate.

The SNSPD detections and the pulse-per-second (PPS) signal produced by the GPS module located at Bob’ side are recorded by a time-to-digital converter (TDC) [qutools] with 81 ps of temporal resolution. In order to time-correlate the two terminals, we developed a synchronization algorithm that is based only on the use of the two GPS modules. At the transmitter, the FPGA is locked to the 10 MHz clock signal from the GPS module, while the PPS signal is used by the FPGA to trigger the transmission of the qubits. To properly compensate for the relative drift between the two GPS modules, we apply a post-processing algorithm to the time of arrival recorded by the TDC. In particular, the qubits detections between two consecutive PPSs are used to estimate the clock frequency of the transmitter with respect to the receiver GPS clock. This information is then used to correct the time interval between the PPSs to make it match with the one of the transmitter. Such an algorithm is able to properly compensate the drift assigning the correct time of arrival of the qubit with an error of about 400 ps (root mean square).

The field trial

Exploiting QCoSOne, we performed multiple QKD runs during the month of April 2019, on several days of clear sky condition. After aligning the two telescopes, and reaching a good SMF coupling efficiency, we aligned the two measurement bases at Bob’s side to Z and X by making Alice send a fixed polarization pattern. Exploiting the APCs in the state analyzer, an ER above 20 dB was obtained for all the polarization states. It is worth noting that the PIC settings were optimized at the beginning of each day, without requiring further changes throughout the whole day. The only observable drifts of our system were due to the SMFs at the receiver and transmitter. However, these drifts were easily compensated by re-aligning the measurement bases, on average, every 2 hours.

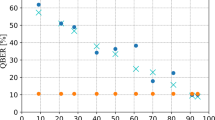

On April 18th we managed to perform the QKD experiment continuously for 8 hours of daylight, as shown in Fig. 2. The total detection rate (TDR, orange line) within a 1ns-wide detection window around the expected arrival time of the pulses (when renormalized taking into account the different quantum efficiencies of the SNSPDs) ranges from 60 to 130 kHz, being around 100 kHz on average. As expected, in our experiment the SMF coupling efficiency and hence the TDR increased approaching the late afternoon, thanks to the reduced turbulence due to the weaker temperature gradient. In daylight, the background rate within the detection window due to environmental light varies, ranging from 200 to 400 Hz and being about 240 Hz on average. Hence, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, blue line) is about 400, while the total losses are around 22 dB on average (5 dB of fixed attenuation due to the optics of the receiver, 5 dB of fixed attenuation in the state analyzer — after the dense WDM filter — and 12 dB due to the mean SMF coupling efficiency at 1550 nm). The drop of the SNR after 18:30 is due to the fact that the receiving telescope was facing toward the sunset, hence increasing the background rate.

We notice that our simulation of the post-processing procedure (see Methods) shows that our setup would be able to produce a secret key (in the asymptotic regime) even with 17 dB of additional losses. These additional losses correspond, if only beam diffraction is considered, to a link distance of about 70 km. Moreover, the SNR can be increased at the expense of a lower sifted rate by narrowing the detection window. In our case, by reducing the detection window to 500 ps, the detection rate decreases by 12%, while the noise is reduced by 50%. For low SNR values, this strategy may result in a higher key rate49.

The measured QBER is <0.75% for all of the 8 hours without the use of any active polarization stabilization system, reaching a value as low as QZ ≈ 0.45% in the Z basis and QX ≈ 0.25% in the X basis. This is the best result to date for a free-space QKD system operating in daylight24,25,26,27,28,29, with performances comparable to fiber-based systems15,17. This result demonstrates that the developed chip encoder is characterized by an excellent polarization stability over time. This feature makes silicon-photonics PICs very attractive in the context of polarization-based satellite QC.

In Fig. 3, we report the results of the different QKD runs performed over three consecutive days. The weather conditions were good on all of the 3 days, with a clear and sunny sky. The Sun reached its maximum elevation (55∘) around 13:00 and the sunset was around 20:00. Each QKD run lasted for the time needed to guarantee that the requirement nZ ≳ 108 was fulfilled. As we showed in Fig. 2, the TDR increased during the day, thus making the effective duration of the QKD runs vary, typically from 15 to 55 min.

Each graph in Fig. 3 shows the rate of the sifted bits nZ (green dots), the asymptotic (infinite-size) SKR (SKR∞, orange dots) and the finite-size SKR (SKRf, blue squares, see Methods for more details) as a function of the hour of the day. Each dot is obtained by an average over 4 min of data acquisition by merging all the runs, while each SKRf point is obtained from a single QKD run. The obtained results are comparable over the 3 days. The sifted bit rate ranges from 50 to 150 kbps, depending essentially on the TDR, hence showing an improvement while approaching the late afternoon. The same trend characterizes also the SKR∞, which ranges from 20 to 70 kbps. We managed to obtain a SKRf of several tens of kbps for all days, reaching a maximum of 65.8 kbps in the last acquisition of April 17th. Remarkably, each QKD run performed on April 18th lasted for about 50 min, allowing to obtain a mean SKRf about 33 kbps.

Many parameters (such as the turbulence level, the channel attenuation, the duration of the demonstration and the type of protocol and key analysis) have to be taken into account to present a comparison as fair as possible with the related QKD works realized at 1550 nm in daylight, that are refs. 28,29 (see Methods). The impact of the turbulence on such links realized in very different conditions can be evaluated by using the ratio D/r050, with D the smaller between the telescope aperture of the receiving telescope and the beam diameter at the receiver and r0 the Fried coherence length51. An estimate of r0 can be obtained by knowing the length and the altitude of the links. Both this demonstration and the experiment over the Qinghai Lake (ref. 28) are characterized by a weak level of turbulence (D/r0 ≲ 3) even though in ref. 28 the link is 53km-long, for which the use of only tip-tilt correction is very effective in enhancing the coupling efficiency52. On the other hand, the 8km-long urban link in Shanghai (ref. 29) is realized under a condition of strong turbulence, and a mere tip-tilt correction is not sufficient. It is worth noting that the model we used is corroborated by the analysis of atmospheric strength on our link we present in the Methods. Regarding the duration of the QKD experiments, our results are obtained over 3 days, with one day of continuous operation over 8 hours and in particular with the Sun at its maximum elevation (around 13:00), when the Shanghai experiment cannot perform QKD due to the hindering turbulence conditions. Moreover, we present our results with finite-key analysis, while the results reported in refs. 28,29 are obtained in the asymptotic limit of infinite key. Then, according to our simulations of the asymptotic secret-key-rate as a function of the fixed losses of the system (due to the different atmospheric transmissions, beams diffraction and optics and detection efficiencies), it results that our protocol outperforms refs. 28,29 for the same amount of fixed losses (10 dB, see Methods). It is also worth noticing that, contrary to refs. 28,29, we exploited only one laser to generate the needed states, thus preventing the possibility of performing a side-channel attack on our implementation53.

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrated the successful realization of a chip-based prototype for free-space QC in daylight, operating at a wavelength in the telecom C-band. We performed several QKD runs obtaining a record-low QBER with our integrated source (the instrinsic was of the order of 0.1% and the one obtained after the propagation in free-space was 0.5%) and a SKR of several tens of kbps, also with the Sun at its maximum elevation. It is worth noticing that intensity and polarization modulations were realized in a single chip used as qubit encoder for decoy-state QKD. Such integrated technology has been used in a real free-space QKD-trial in an urban area, thanks to the dedicated packaging designed and realized to the purpose. We overcame the strong background noise generated by direct and diffuse sunlight by exploiting temporal (i.e., synchronization), spatial (i.e., single-mode fibers) and wavelength (i.e, dense WDM) filters. We modeled and measured the impact of the turbulence on the used link, showing the effectiveness of the developed PAT system in guaranteeing a stable coupling of the free-space signal into the SMF. Our solution is very attractive for the design and development of optical payloads to be placed in portable terminals or satellites dedicated to QC, given the low resources needed in terms of power, weight and space.

Further improvements to our prototype can be achieved by increasing the system clock rate, for example up to 1 GHz (as in refs. 7,17,31,32), and exploiting adaptive optics to increase the SMF coupling efficiency50 and thus the tolerable losses and achievable link distance. However, the obtained results show that daylight QKD technology is mature enough to foresee the real application of a global scale QC-network in the next future21,23. It will likely comprise free-space, satellite and fiber-based channels exploiting quantum technologies to accomplish tasks such as QKD, realizable also in the device- or measurement-device independent framework54,55, entanglement distribution56, quantum teleportation57 and quantum time distribution58, as envisaged by the Italian Quantum Backbone59, a fiber-based infrastructure connecting the National Institute of Metrological Research in Turin with the Space Center of the Italian Space Agency in Matera.

Methods

Description of the QKD protocol

In our prototype, we chose to realize the 3-state 1-decoy version of the efficient BB84 protocol proposed by Rusca et al.5, due to the reduced complexity of the implementation when exploiting polarization encoding. The protocol works as follows.

Alice randomly encodes a weak coherent pulse either in the \(Z=\{\left|0\right\rangle ,\left|1\right\rangle \}\) basis, with probability \({p}_{A}^{Z}\), or in the \(X=\{\left|+\right\rangle ,\left|-\right\rangle \}\) basis, with probability \({p}_{A}^{X}=1-{p}_{A}^{Z}\). The basis X is Mutually Unbiased with respect to Z, namely ∣〈0∣ ± 〉∣2 = ∣〈1∣ ± 〉∣2 = 1/2. In our implementation, we have chosen \(\left|0\right\rangle := \left|L\right\rangle =(\left|H\right\rangle -i\left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), \(\left|1\right\rangle := \left|R\right\rangle =(\left|H\right\rangle +i\left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\left|\pm \right\rangle := (\left|H\right\rangle \pm \left|V\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\). Alice needs to generate only three polarization states, \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle\) with uniform probability for the Z basis, and \(\left|+\right\rangle\) for the X one. The intensity level of the pulse is randomly chosen between two values, μ1 and μ2, with probabilities \({p}_{{\mu }_{1}}\) and \({p}_{{\mu }_{2}}=1-{p}_{{\mu }_{1}}\), respectively. The two values can differ between pulses prepared in X and Z (\({\mu }_{1}^{X}\,\ne\, {\mu }_{1}^{Z}\), \({\mu }_{2}^{X}\,\ne\, {\mu }_{2}^{Z}\)), because we carry out the yield analysis separately in the two bases45. This procedure allows to detect a possible photon-number-splitting attack60.

Bob, at his site, measures the incoming photons in the two bases Z and X, with probability \({p}_{B}^{Z}\) and \({p}_{B}^{X}=1-{p}_{B}^{Z}\), respectively. After the photons exchange, Alice and Bob announce, for each detected event, their basis choices. Then, nZ raw sifted bits are obtained from pulses sent and detected in the Z basis, while the ones from the X basis are used to estimate the information leakage toward a potential eavesdropper.

After generating a raw key, Alice and Bob proceed with the error correction (EC) and the finite-key privacy amplification (PA) steps, ultimately obtaining, for each PA block, a secure secret key of l bits, which is bounded by5:

where sZ,0 and sZ,1 are the lower bounds on the number of vacuum and single-photon detections in the Z basis, ϕZ is the upper bound on the phase error rate corresponding to single photon pulses, h( ⋅ ) is the binary entropy, λEC = fECnZh(QZ) is the total number of bits revealed during the EC step — which depends on the reconciliation efficiency of the EC algorithm (Cascade, in our case fEC ≈ 1.06), the number of raw key bits nZ, and on the QBER QZ — and \({\epsilon }_{\sec }=1{0}^{-10}\), ϵcor = 10−12 are the secrecy and the correctness parameters, respectively5. The results for the different QKD runs presented in this work were obtained by adapting the AIT QKD R10 software suite by the AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH61 (https://sqt.ait.ac.at/software/projects/qkd) to our needs. The data post-processing can be performed on any modern personal computer, since it does not require a great computational load.

Additional details on the PAT system

The complete setup comprising the PAT system is presented in Fig. 1b and c, and it is based on a coarse-alignment system followed by a fine-alignment stage, in charge of the SMF coupling. The former is based on the use of two counter-propagating beacon lasers (at 635 and 850 nm of wavelength) which are acquired by a CMOS camera at both terminals to guarantee a rough alignment between the two telescopes. The fine alignment is achieved by controlling in closed-loop the FSM with the feedback signal provided by the PSD acquiring the 1064-nm beacon laser sent by Alice, as described in the main text. The whole alignment from scratch requires about 40 min through a procedure divided into different steps and it was necessary only in the first day. All the steps are not needed to be repeated at the beginning of each day, thus shortening the time to start the QKD exchange. The coupling efficiency is estimated by monitoring the power into the SMF (after the dense WDM filter) collected from an auxiliary beacon at 1545 nm of wavelength. In fact, the 1545-nm beacon and the quantum signal at 1550 nm exit from the two different outputs of the WDM filter, which are characterized by different losses. By taking into account this difference, the mean coupling efficiency into the SMF just before the WDM filter is 8.5%, which reduces to ρ0[1545nm] = 4% and ρ0[1550 nm] = 6% for the two outputs.

To evaluate the performance of the PAT system, we performed some acquisitions lasting for 5 min with the tip-tilt correction on and off, comparing the effects on centroid fluctuations and on the power at 1545 nm coupled into the SMF, as shown in Fig. 4a for data taken on April 17th at 12:30 (without performing QKD). The root-mean-square (RMS) of centroid fluctuations on the PSD without tip-tilt correction is RMSoff = 120 μm, corresponding to angle-of-arrival (AoA) fluctuations in front of the receiving telescope of αoff = 15 μrad. With active tip-tilt correction, these fluctuations are reduced to RMSon = 1.5 μm, corresponding to residual AoA fluctuations αon = 0.2 μrad. The closed-loop bandwidth of the feedback system is around 25 Hz, which is enough for compensating most of the spectrum of AoA fluctuations.

The effect of the active tip/tilt stabilization on the SMF coupling efficiency of the 1545-nm beacon (measured after the dense WDM filter) is shown in Fig. 4b, where the histogram shows the statistical distribution of the coupling efficiency. For this particular acquisition, the mean coupling efficiency ρ0[1545nm] increases from 2.9% to 9.5% (equivalently, from 15 to 10 dB), thanks to the suppression of global beam displacements on the focal plane. It is worth noting that the receiver FOV of 5 μrad is defined as the half-angle fluctuation at which the SMF coupling efficiency is reduced to 50% of its maximum value, and the coupling efficiency is essentially constant for AoA ≲ 1μrad. Given the residual AoA fluctuation measured with the active correction (αon = 0.2 μrad), the reduction in the experimental coupling efficiency is then only imputable to the higher orders of turbulence, which our system does not correct for.

To analyse these effects, and get some information on the turbulence strength on our link, based on the standard Kolmogorov’s treatment used in adaptive optics51, we applied the model described in ref. 62 to the histograms of the coupling efficiency. This model takes into account the variances of the amplitude of the Zernike modes associated to the different aberrations, and it is particularly effective when applied to the data taken with active tip-tilt correction, since in this case the variances related to tip and tilt amplitudes can be set to zero. Such a fit on the blue distribution returns a Fried coherence length at 1550 nm of \({r}_{0}^{({\rm{fit}})}=8.9\) cm (corresponding to a refractive-index structure constant \({C}_{n}^{2({\rm{fit}})}=1.1\cdot 1{0}^{-13}\,{\text{m}}^{-2/3}\)) and a maximum achievable coupling efficiency (without turbulence) \({\rho }_{0}^{({\rm{fit}})}=34.3 \%\) ( ≈ 5 dB). It is worth noting that \({r}_{0}^{({\rm{fit}})}\) and \({C}_{n}^{2({\rm{fit}})}\) are comparable with the values obtained with the standard model of atmospheric strength51:

where L is the link length, λ = 1550 nm is the signal wavelength, and \({C}_{n}^{2}\) is assumed to be constant along the propagation path. Equation. (2) applied to our link in Padua (PD) yields \({r}_{0}^{({\rm{PD}})}\,=\,4.2\) cm with \({C}_{n}^{2({\rm{PD}})}\,=\,1.9\,\cdot \,1{0}^{-13}\,{\text{m}}^{-2/3}\). Moreover, the value \({\rho }_{0}^{({\rm{fit}})}\) is well aligned with the one estimated from the optical simulation of our receiving system, which provides a maximum achievable coupling efficiency of 33.4%. To attest the robustness of our analysis, we used the parameters extracted from the fit to superimpose the red line on the distribution obtained with the control off, where the fitting procedure was not effective.

Comparison with other QKD experiments at 1550 nm in daylight

We summarize in Table 1 the parameters used to compare the impact of turbulence on the different QKD experiments realized at 1550 nm in daylight, that are refs. 28,29. The Fried parameter is estimated according to Eq. (2) for the three links. We report the value of the ratio D/r0 used to attest the impact of turbulence on the system, the losses due to the single-mode-fiber (SMF) coupling at 1550 nm and the fixed losses occurring in the demonstration. These are reported in the cited works, and they depend on the different length of the links and on the different size of the beams and of the telescope apertures, as well as on the different detection systems used. All the experiments are realized in conditions that are very different from the ones obtained in laboratory, and are significant to evaluate the feasibility of daylight QKD at 1550 nm. We present in Fig. 5 the simulation of the three experiments showing the asymptotic secret-key-rate (SKR) as a function of the fixed losses, hence assuming the same turbulence level and the same SMF-coupling efficiency while varying essentially the link distance. The diamonds represent the best QKD run of each work. It is worth noting that our protocol performs better than the one implemented in the other works up to 23 dB of fixed attenuation.

Even if our experiment has been performed over sunny days, it is interesting to investigate how our system would perform under bad weather conditions, such as rain and snow. In this regard, in the literature (see ref. 63 and references therein) there exist models that allow to estimate the link attenuation up to a certain level of rain or snow fall rate, which is usually expressed in millimeter per hour (mm/h). We show in Fig. 6 the asymptotic SKR we would expect as a function of different fall rates by applying the model of ref. 63 to the 145-m link used in the experiment. It is evident that both the scenarios would reduce the SKR, but the production of a secure key would still be possible even under heavy rain or snow conditions (around 30 mm/h).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions of this work are presented in the manuscript. Additional data related to this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that contributed to the results of this study is available on reasonable request from the authors.

References

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002).

Scarani, V. et al. The security of practical quantum key distribution. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1301–1350 (2009).

Diamanti, E., Lo, H.-K., Qi, B. & Yuan, Z. Practical challenges in quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 16025 (2016).

Pirandola, S. et al. Advances in quantum cryptography. Opt. Photon. 12, 1012–1236 (2020).

Rusca, D., Boaron, A., Grünenfelder, F., Martin, A. & Zbinden, H. Finite-key analysis for the 1-decoy state qkd protocol. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 171104 (2018).

Lucamarini, M., Yuan, Z. L., Dynes, J. F. & Shields, A. J. Overcoming the rate–distance limit of quantum key distribution without quantum repeaters. Nature 557, 400–403 (2018).

Boaron, A. et al. Secure quantum key distribution over 421 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 190502 (2018).

Minder, M. et al. Experimental quantum key distribution beyond the repeaterless secret key capacity. Nat. Photonics 13, 334–338 (2019).

Agnesi, C., Avesani, M., Stanco, A., Villoresi, P. & Vallone, G. All-fiber self-compensating polarization encoder for quantum key distribution. Opt. Lett. 44, 2398–2401 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental twin-field quantum key distribution through sending-or-not-sending. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 100505 (2019).

Liao, S.-K. et al. Satellite-to-ground quantum key distribution. Nature 549, 43–47 (2017).

Bedington, R., Arrazola, J. M. & Ling, A. Progress in satellite quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 30 (2017).

Agnesi, C. et al. Exploring the boundaries of quantum mechanics: advances in satellite quantum communications. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. A 376, 20170461 (2018).

Khan, I., Heim, B., Neuzner, A. & Marquardt, C. Satellite-based qkd. Opt. Photon. News 29, 26 (2018).

Yoshino, K.-I., Ochi, T., Fujiwara, M., Sasaki, M. & Tajima, A. Maintenance-free operation of wdm quantum key distribution system through a field fiber over 30 days. Opt. Express 21, 31395 (2013).

Islam, N. T., Lim, C. C. W., Cahall, C., Kim, J. & Gauthier, D. J. Provably secure and high-rate quantum key distribution with time-bin qudits. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701491 (2017).

Yuan, Z. et al. 10-mb/s quantum key distribution. J. Light. Technol. 36, 3427–3433 (2018).

Agnesi, C. et al. Simple quantum key distribution with qubit-based synchronization and a self-compensating polarization encoder. Optica 7, 284–290 (2020).

Peev, M. et al. The SECOQC quantum key distribution network in vienna. New J. Phys. 11, 075001 (2009).

Sasaki, M. et al. Field test of quantum key distribution in the tokyo qkd network. Opt. Express 19, 10387–10409 (2011).

Kimble, H. J. The quantum internet. Nature 453, 1023–1030 (2008).

Pirandola, S. & Braunstein, S. L. Physics: Unite to build a quantum internet. Nature 532, 169–171 (2016).

Wehner, S., Elkouss, D. & Hanson, R. Quantum internet: A vision for the road ahead. Science 362, eaam9288 (2018).

Buttler, W. T. et al. Daylight quantum key distribution over 1.6 km. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5652–5655 (2000).

Hughes, R. J., Nordholt, J. E., Derkacs, D. & Peterson, C. G. Practical free-space quantum key distribution over 10 km in daylight and at night. New J. Phys. 4, 43–43 (2002).

Peloso, M. P., Gerhardt, I., Ho, C., Lamas-Linares, A. & Kurtsiefer, C. Daylight operation of a free space, entanglement-based quantum key distribution system. New J. Phys. 11, 045007 (2009).

Ko, H. et al. Experimental filtering effect on the daylight operation of a free-space quantum key distribution. Sci. Rep. 8, 15315 (2018).

Liao, S.-K. et al. Long-distance free-space quantum key distribution in daylight towards inter-satellite communication. Nat. Photonics 11, 509–513 (2017).

Gong, Y.-H. et al. Free-space quantum key distribution in urban daylight with the spgd algorithm control of a deformable mirror. Opt. Express 26, 18897 (2018).

Ma, C. et al. Silicon photonic transmitter for polarization-encoded quantum key distribution. Optica 3, 1274–1278 (2016).

Sibson, P. et al. Integrated silicon photonics for high-speed quantum key distribution. Optica 4, 172 (2017).

Bunandar, D. et al. Metropolitan quantum key distribution with silicon photonics. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021009 (2018).

Agnesi, C. et al. Hong-Ou-Mandel interference between independent III–V on silicon waveguide integrated lasers. Opt. Lett. 44, 271–274 (2019).

Krainak, M. et al. Integrated photonics for NASA applications. In Components and Packaging for Laser Systems V, vol. 10899 (SPIE, 2019).

Anzalchi, J., Inigo, P. & Roy, B. Application of photonics in next generation telecommunication satellites payloads. In International Conference on Space Optics 2014, vol. 10563 (SPIE, 2017).

Fidler, F. & Wallner, O. Application of single-mode fiber-coupled receivers in optical satellite to high-altitude platform communications. J. Wireless Com. Network 2008, 864031 (2008).

Takenaka, H., Toyoshima, M. & Takayama, Y. Experimental verification of fiber-coupling efficiency for satellite-to-ground atmospheric laser downlinks. Opt. Express 20, 15301–15308 (2012).

Europractice IC Service. http://www.europractice-ic.com/index.php.

Velha, P. et al. Wide-band polarization controller for si photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Lett. 41, 5656–5659 (2016).

Absil, P. P. et al. Imec iSiPP25G silicon photonics: a robust CMOS-based photonics technology platform. In Silicon Photonics X, vol. 9367 (SPIE, 2015).

Oi, D. K. et al. Cubesat quantum communications mission. EPJ Quantum Technol. 4, 6 (2017).

Nordholt, J. E., Peterson, C. G., Newell, R. T. & Hughes, R. J. Quantum communications system with integrated photonic devices. US Patent N. 9,819,418 (2017).

Raffaelli, F. et al. Generation of random numbers by measuring phase fluctuations from a laser diode with a silicon-on-insulator chip. Opt. Express 26, 19730–19741 (2018).

Tosi, A., Frera, A. D., Shehata, A. B. & Scarcella, C. Fully programmable single-photon detection module for InGaAs/InP single-photon avalanche diodes with clean and sub-nanosecond gating transitions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 013104 (2012).

Yu, Z.-W., Zhou, Y.-H. & Wang, X.-B. Reexamination of decoy-state quantum key distribution with biased bases. Phys. Rev. A 93, 032307 (2016).

Avesani, M., Marangon, D. G., Vallone, G. & Villoresi, P. Source-device-independent heterodyne-based quantum random number generator at 17 gbps. Nat. Commun. 9, 5365 (2018).

Fung, C. F., Tamaki, K., Qi, B., Lo, H. & Ma, X. Security proof of quantum key distribution with detection efficiency mismatch. Quantum Inf. Comput. 9, 131–165 (2009).

Bochkov, M. K. & Trushechkin, A. S. Security of quantum key distribution with detection-efficiency mismatch in the single-photon case: Tight bounds. Phys. Rev. A 99, 032308 (2019).

Vallone, G. et al. Adaptive real time selection for quantum key distribution in lossy and turbulent free-space channels. Phys. Rev. A 91, 042320 (2015).

Chen, M., Liu, C. & Xian, H. Experimental demonstration of single-mode fiber coupling over relatively strong turbulence with adaptive optics. Appl. Opt. 54, 8722–8726 (2015).

Tyson, R. K. Principles of Adaptive Optics. 4 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2015).

Dikmelik, Y. & Davidson, F. M. Fiber-coupling efficiency for free-space optical communication through atmospheric turbulence. Appl. Opt. 44, 4946–4952 (2005).

Lee, M. S. et al. Quantum hacking on a free-space quantum key distribution system without measuring quantum signals. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 36, B77–B82 (2019).

Acín, A. et al. Device-independent security of quantum cryptography against collective attacks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 230501 (2007).

Liu, H. et al. Experimental demonstration of high-rate measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over asymmetric channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 160501 (2019).

Yin, J. et al. Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers. Science 356, 1140–1144 (2017).

Ren, J.-G. et al. Ground-to-satellite quantum teleportation. Nature 549, 70–73 (2017).

Kómár, P. et al. A quantum network of clocks. Nat. Phys. 10, 582 (2014).

Calonico, D. A fibre backbone in italy for precise time and quantum key distribution. 4th ETSI/IQC Workshop on Quantum-Safe Cryptography, Toronto 19-21 Sep 2016

Lütkenhaus, N. Security against individual attacks for realistic quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. A 61, 052304 (2000).

AIT QKD R10 Software. https://sqt.ait.ac.at/software/projects/qkd.

Canuet, L. et al. Statistical properties of single-mode fiber coupling of satellite-to-ground laser links partially corrected by adaptive optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 35, 148–162 (2018).

Singh, H. & Chechi, D. P. Performance evaluation of free space optical (fso) communication link: Effects of rain, snow and fog. In 2019 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), 387–390 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Italian Space Agency for support, and specifically Dr. Alberto Tuozzi and Dr. Claudia Facchinetti of the Telecommunication and Navigation division. This work was funded by the project QCommSpaceOne of the Italian Space Agency (ASI, Accordo n. 2017-4-H.0): “Space Quantum Communications between Space and Earth: conception of a flight terminal and development of a prototype”. We thank Iyad Suleiman for his contribution in the early development of the fiber-injection system. We thank Lorenzo Franceschin and Achille Forzan of the Department of Information Engineering of the University of Padua for logistic support to realize the field trial. We thank Christoph Pacher, Oliver Maurhart and the AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH for providing the foundation for the post-processing software. We thank the CloudVeneto facility for the computational resources. M.Z. acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 675662. Part of this work was supported by MIUR (Italian Minister for Education) under the initiative “Departments of Excellence” (Law 232/2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The positive outcome of the work has been possible only with the combined and tenacious efforts of all the authors. P.V. conceived the project. F.V., G.V., and P.V. supervised and coordinated the project. The QKD source was mainly designed and developed by M.Av., and A.Sa., with help from A.St., C.A. and F.V., while M.Av. and F.V. mainly designed and tested the state analyzer. M.Z. and L.C. developed the software for the automatic polarization controllers. The optical setup of the two terminals was designed and developed mainly by M.S., with substantial contributions from L.C., M.Z., and A.Sc. In particular, M.S. and A.Sc. developed the fiber-injection system at the receiver, while M.Z. and L.C. developed the automatic pointing system of the transmitter. The FPGA-based control electronics of the system was developed by A.St., with help by M.Av. The synchronization technique, as well as the processing of the QKD data, were mainly developed by L.C. G.F. performed the secret key analysis, with help from M.S., L.C. and M.Av. M.Ar., M.R. and G.C supervised the realization of the PIC. A.Sa. and V.S. designed the PIC. A.M. and M.Ar. characterized the fabricated batch of PICs to verify design specs and check functionality of the encoders. A.M., M.Av. and C.A. characterized and tested in detail the PICs selected for the field trial (prior to and post packaging). M.C. and D.R. designed and realized the package of the selected chips. C.A., M.Av., L.C., G.F., M.S., A.Sc., A.St., F.V., and M.Z. realized the field trial. All authors discussed the results. F.V. wrote the paper with input from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Avesani, M., Calderaro, L., Schiavon, M. et al. Full daylight quantum-key-distribution at 1550 nm enabled by integrated silicon photonics. npj Quantum Inf 7, 93 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00421-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00421-2

This article is cited by

-

Improved security bounds against the Trojan-horse attack in decoy-state quantum key distribution

Quantum Information Processing (2024)

-

Prospects and applications of on-chip lasers

eLight (2023)

-

Towards metropolitan free-space quantum networks

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

A hybrid integrated quantum key distribution transceiver chip

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Satellite-based quantum information networks: use cases, architecture, and roadmap

Communications Physics (2023)